Abstract

Cytokinin (CK) is the primary hormone that positively regulates axillary bud outgrowth. However, in many woody plants, such as Jatropha curcas, gibberellin (GA) also promotes shoot branching. The molecular mechanisms underlying GA and CK interaction in the regulation of bud outgrowth in Jatropha remain unclear. To determine how young axillary buds respond to GA3 and 6-benzyladenine (BA), we performed a comparative transcriptome analysis of the young axillary buds of Jatropha seedlings treated with GA3 or BA. Two hundred and fifty genes were identified to be co-regulated in response to GA3 or BA. Seven NAC family members were down-regulated after treatment with both GA3 and BA, whereas these genes were up-regulated after treatment with the shoot branching inhibitor strigolactone. The expressions of the cell cycle genes CDC6, CDC45 and GRF5 were up-regulated after treatment with both GA3 and BA, suggesting they may promote bud outgrowth via regulation of the cell cycle machinery. In the axillary buds, BA significantly increased the expression of GA biosynthesis genes JcGA20oxs and JcGA3ox1, and down-regulated the expression of GA degradation genes JcGA2oxs. Overall, the comprehensive transcriptome data set provides novel insight into the responses of young axillary buds to GA and CK.

Introduction

The plant above-ground architecture is primarily due to the complex spatial-temporal regulation of shoot branching. After axillary bud formation, the bud can undergo immediate outgrowth or become dormant or quiescent1–3. Axillary bud activity is closely correlated with various endogenous and environmental stimuli, such as phytohormones, light, and nutrients4. Among these environmental signals, light is a major factor that affects plant development5. Plants can modulate shoot branching to obtain maximum light radiation for increased production of photosynthetic products, primarily sucrose. In pea, sucrose itself has been implicated in the regulation of bud outgrowth6. The endogenous phytohormones levels are, in part, a reflection of the growth conditions that plants are subjected to7. Two types of hormones are involved in the regulation of bud outgrowth: cytokinin (CK), the major hormone promoting bud outgrowth8, and auxin and strigolactones (SLs), both of which inhibit bud outgrowth9–11. However, at the molecular level, how these hormones regulate bud outgrowth remains elusive. BRANCHED1 (BRC1), which encodes a transcription factor, inhibits axillary bud outgrowth in many species (e.g., pea, Arabidopsis and rice)12–14. In pea and Arabidopsis, BRC1 expression is negatively regulated by CK but induced by GR24 (a synthetic analog of SL)14–16. However, BRC1 levels are not affected by GR24 treatment in rice13.

Auxins are traditionally a group of phytohormones involved in the regulation of growth and development of plants, the efflux of which is important for axillary bud outgrowth8. Thus far, most studies have focused on the interactions of auxins, CKs and SLs in the regulation of bud outgrowth1. Other hormones, such as gibberellins (GAs), were also considered to be involved in the regulation of bud outgrowth, although its effects in different species vary a lot4. In rice and Arabidopsis, GA plays a negative role in controlling shoot branching17, 18. Recently, we observed that in many perennial woody plants, such as Jatropha curcas and papaya, GA is a positive regulator of axillary bud outgrowth19. In sweet cherry, GA treatment also promoted shoot branching in the spring after bud break20. In hybrid aspen, GA biosynthesis is crucial in axillary bud formation and activation2. These findings demonstrated that in many perennial woody plants, the regulation of shoot branching may differ from that in annual, herbaceous plants, such as Arabidopsis, pea and rice. The involvement of GAs complicates the regulatory network of axillary bud outgrowth. Nevertheless, the molecular mechanisms of how GAs, through interactions with CK, regulate shoot branching in Jatropha remain elusive.

In recent years, numerous studies on various aspects of the biofuel woody plant J. curcas have been reported, including seed development21, seed oil biosynthesis22, seed toxicity23, 24, flower development25 and adaptations to biotic and abiotic stresses26–29, genome and transcriptome studies30–35 and shoot branching governed by different phytohormones19, 36. In J. curcas, GA and CK are positive regulators of shoot branching and corporately regulate the axillary bud outgrowth in antagonism with some other hormones, such as SLs and auxin19. Immediate bud outgrowth can be detected a few days after gibberellin A3 (GA3) or 6-benzyladenine (BA, a synthetic CK) treatment. Quantitative real-time PCR analyses have shown that GA3 and BA have common target genes, such as JcBRC1, JcBRC2 and JcMAX2 19, key inhibitors of bud outgrowth in pea, rice and Arabidopsis 12, 16, 37–42. These results suggest that the downstream regulatory networks of bud outgrowth mediated by these two hormones could interact in J. curcas 19.

Transcriptome sequences generated using high-throughput sequencing techniques are efficient and data-rich43. High-throughput sequencing is an effective method to identify the candidate genes or pathways involved in the regulation of different biological processes at the transcriptome level. To advance the current understanding of how the young axillary buds respond to exogenously applied GA3 or BA in J. curcas, we performed transcriptome analyses of the nodal stem after mock, GA3 and BA treatments. Subsequent comparisons of the global expression profiles of mock-, GA3- or BA-treated samples enabled the identification of many GA3- and BA-responsive genes. Specifically, the identification of the common target genes of these two hormones would help in selecting candidates involved in the regulation of axillary bud outgrowth in J. curcas. Further detailed analyses of the function of these genes could provide novel insights into the regulatory network of phytohormones that control axillary bud outgrowth.

Results and Discussion

Identification of differentially expressed genes (DEGs) in response to GA3 and BA

We previously reported that exogenous treatment with GA3 or BA effectively promote the axillary bud outgrowth in J. curcas (Fig. S1), by suppressing negative regulators of shoot branching, such as JcBRC1, JcBRC2, and JcMAX2 19. To obtain further insights into the genetic regulation of the young axillary buds response to GA3 or BA at a genome-wide level, we performed an RNA sequencing-based transcriptome analysis of Jatropha young axillary buds exposed to GA3 or BA treatment. Then, we identified the candidate genes involved in the regulation of the axillary bud outgrowth in J. curcas. Approximately 12 million clean reads per sample (biological replicate) were obtained from the mock, GA3 and BA experimental groups (Table S1). A plot showing the relationships among 9 samples from the three groups (mock, GA3 and BA) was generated based on multidimensional scaling through the “plotMDS.dge” function of the edgeR package44 (Fig. S2). The results clearly showed the nine samples were well separated into three groups, indicating the good repeatability of the RNA-seq results. Together with the relative high value of Q30 and high percentage of mapped reads from the nine samples of the three groups (Table S1), these analysis suggested that the RNA-seq result is qualified for further downstream analysis.

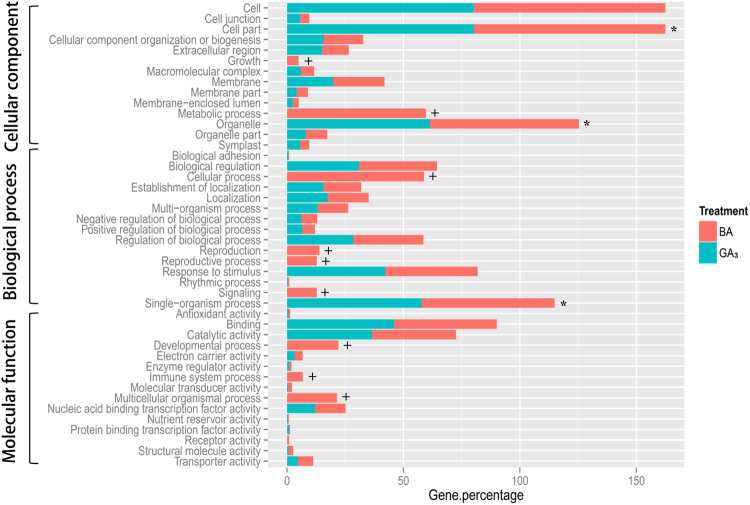

Transcriptome analysis showed that 1365 genes were down-regulated and 1357 genes were up-regulated after GA3 treatment, whereas 2619 genes were down-regulated and 2728 genes were up-regulated after BA treatment (false discovery rate (FDR) < 0.05) (Fig. S3), implying that BA is a more general regulator than GA3 in the axillary bud outgrowth in Jatropha seedlings. The differentially expressed genes (DEGs) with a threshold of fold change ≥ 2 and FDR value ≤ 0.05, including 1141 DEGs from BA treatment (Table S2) and 429 DEGs from GA3 treatment (Table S3), were chosen for further analysis. Gene Ontology (GO) annotation showed that the DEGs of GA3 or BA treatment were predominantly classified in the “cell part”, “organelle” and “single-organism process” categories (Fig. 1). However, many of the DEGs belonging to the “metabolic process”, “cellular process”, “multicellular organismal process”, “reproduction”, “reproductive process”, “developmental process”, “signaling” and “growth” categories were present after BA treatment but not after GA3 treatment (Fig. 1, and Table S4).

Figure 1.

GO analysis of the DEGs by GA3 or BA treatment. DEGs were assigned to three categories: cellular component, biological process and molecular function. The most abundant terms were marked with “*”; BA-specific GO terms were marked with “+”. Gene percentage was calculated as: number of DEGs in one GO term/number of total analyzed DEGs.

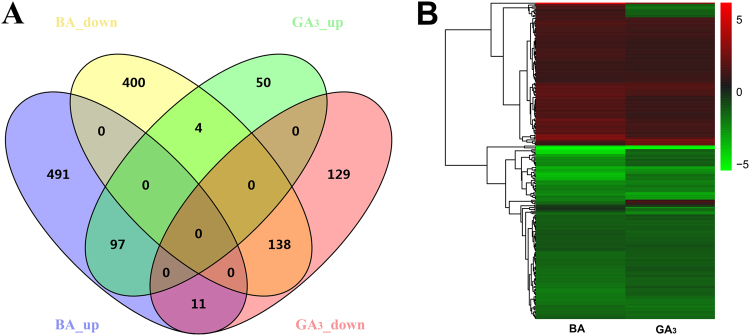

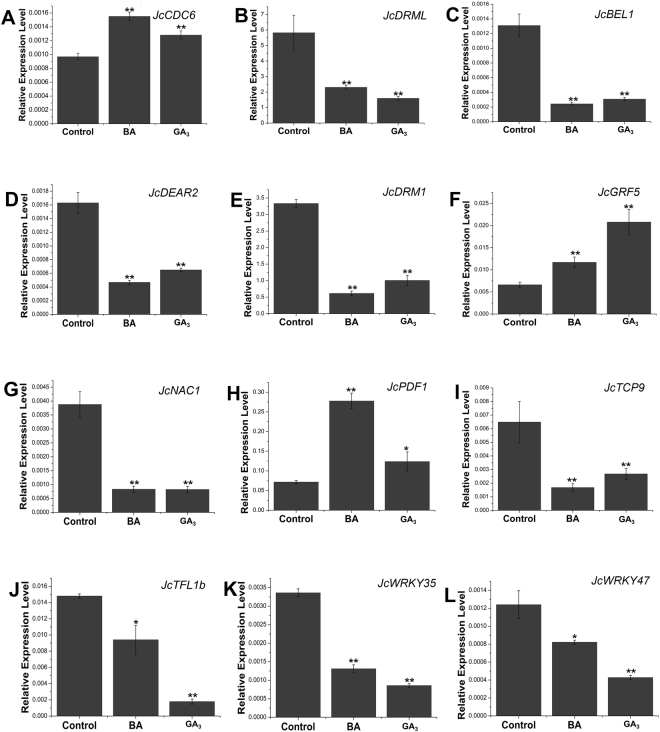

Among the DEGs identified in this study, there are 891 DEGs specifically regulated by BA, 179 DEGs by GA3, and 250 co-regulated genes that responded to both GA3 and BA (Fig. 2A and Tables S5–S7). The expression clustering analysis of the 250 co-regulated genes showed that most of these genes had similar expression patterns in the GA3- and BA-treated groups (Fig. 2B). Among the 250 co-regulated DEGs, a total of 97 genes were up-regulated, and 138 genes were down-regulated in both the GA3- and BA-treated groups, and only 15 genes were differentially expressed in these two groups (Fig. 2A and Table S5). The GO analysis showed the most abundant GO terms of the 97 co-up-regulated DEGs were “compound/protein binding”, “metabolic process” and “biosynthetic process”, indicating the accelerated cell activity during the axillary bud outgrowth (Table S8). In contrast, the 138 co-down-regulated DEGs were mostly distributed in response pathways, such as “response to stress”, “response to chemical”, and “response to endogenous stimulus” (Table S9), which may result from a trade-off between active growth and defense to biotic and abiotic stress45, 46. Among the 15 differentially co-regulated DEGs (Table S5), three were identified to encode enzymes of GA biosynthesis (JcGA20ox2, Cluster-26.16883) and degradation (JcGA2ox2, Cluster-26.9482 and JcGA2ox4, Cluster-26.18818), and two are GA-responsive genes JcGASA6 (GA-regulated family protein, Cluster-26.3799)47 and JcBG3 (1,3-β-glucanase 3, Cluster-545.0), whose homologs in hybrid aspen were involved in axillary bud dormancy release and branching2, 48. To validate the expression profiles of these co-regulated genes, we selected 12 transcription factors, whose homologs are involved in the regulation of shoot branching (JcBEL1, JcDRM1, JcDRML, and JcTFL1b) and cell division (JcCDC6, JcGRF5, and JcNAC1), or belong to the well characterized families of plant transcription factors (JcDEAR2, JcPDF1, JcTCP9, JcWRKY35, and JcWRKY47), for qPCR analysis. The results were consistent with the transcriptome data (Fig. 3, Table S5). In addition, the different expression profiles of the GA biosynthesis gene GA20ox2 (Cluster-26.16883) and the GA degradation genes GA2ox2 (Cluster-26.9482) and GA2ox4 (Cluster-26.18818) between GA3 and BA treatment, which were revealed by the transcriptome data (Table S5), were also confirmed by qPCR analyses (Figs 4 and S4). Taken together, at the transcriptome level, these results demonstrated that bud outgrowth in J. curcas could be cooperatively regulated by GA3 and BA.

Figure 2.

Venn diagram (A) and heat map clustering (B) of the co-regulated genes by GA3 and BA treatment. The input information was listed in Table S5. TMM-normalized fragments per kilobase of transcript per million fragments sequenced (FPKM) values were log-transformed prior to clustering.

Figure 3.

Quantitative real-time PCR analysis of the transcription factors regulated by both GA3 and BA treatment. The expression of JcCDC6 (A, Cluster-2004.0), JcDRML (B, Cluster-26.12832), JcBEL1 (C, Cluster-26.17792), JcDEAR2 (D, Cluster-26.17120), JcDRM1 (E, Cluster-26.5833), JcGRF5 (F, Cluster-26.21078), JcNAC1 (G, Cluster-26.19073), JcPDF1 (H, Cluster-26.15852), JcTCP9 (I, Cluster-26.19926), JcTFL1b (J, Cluster-26.17723), JcWRKY35 (K, Cluster-26.10011) and JcWRKY47 (L, Cluster-1476.0) was analyzed in the buds of Jatropha seedlings at 12 h. GAPDH was used as the internal reference. The error bars represent SE (n = 3). Student’s t-test was used to determine significant differences between the indicated and control groups. Significance levels: *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01.

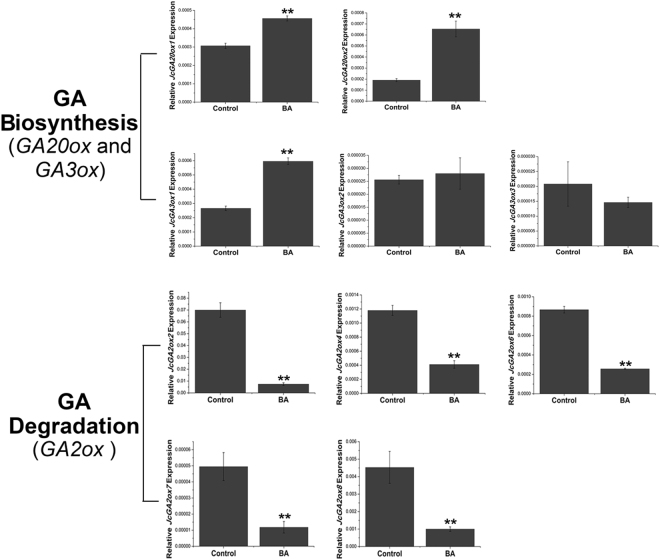

Figure 4.

BA regulates GA metabolism in the buds. BA promoted the expression of the GA biosynthesis genes JcGA20ox1, JcGA20ox2 and JcGA3ox1, and simultaneously inhibited the expression of all GA degradation genes JcGA2oxs in J. curcas. Cluster IDs: JcGA20ox1, Cluster-26.319; JcGA20ox2, Cluster-26.16883; JcGA3ox1, Cluster-26.16438; JcGA3ox2, Cluster-26.14433; JcGA3ox3, Cluster-26.14518; JcGA2ox2, Cluster-26.9482; JcGA2ox4, Cluster-26.18818; JcGA2ox6, Cluster-26.14996; JcGA2ox7, Cluster-26.16004; JcGA2ox8, Cluster-26.18801. GAPDH was used as the internal reference. The error bars represent SE (n = 3). Student’s t-test was used to determine the significant differences between the indicated and control groups. Significance levels: **P < 0.01.

Bud outgrowth and dormancy-related genes are commonly regulated by GA3 or BA

Most dormant axillary bud cells in the annual plants Arabidopsis or pea are believed to be blocked in G1 phase, and the cell cycle can be reactivated concomitantly with the initiation of bud outgrowth49–51. Cell division control (CDC) proteins, such as CDC6 and CDC45, are important regulators of the cell cycle that are ubiquitously found in animals, plants and fungi52–58. After GA3 or BA treatment, the expression of JcCDC6 (Cluster-2004.0) and JcCDC45 (Cluster-26.14626) was significantly increased (Fig. 3A and Table S5). The expressions of three genes encoding DNA primase-polymerase (JcPrimPol, Cluster-26.12318), DNA polymerase alpha subunit B (JcPOLA2, Cluster-609.2) and the catalytic subunit of DNA polymerase α (JcICU2, Cluster-761.0) were up-regulated by both GA3 and BA treatment (Table S5). Moreover, the expression of another important plant growth regulator GRF5 (Cluster-26.21078), which is involved in the regulation of cell proliferation in the leaf primordia59, was also increased in the axillary bud after GA3 or BA treatment (Fig. 3F and Table S5). These results suggested that bud outgrowth promoted by GA3 or BA in J. curcas may be due, in part, to triggering the cell cycle machinery, which could be one of the key points where different phytohormones convergently regulate initiation of the axillary bud outgrowth.

Two other genes, BELL1 (BEL1) and TERMINAL FLOWER 1 (TFL1), are both potential negative regulators of shoot branching in Arabidopsis 59–61. In sorghum, the expression levels of BEL1 and TFL1 were much higher in the axillary bud of the phyb mutant, which showed a restricted shoot branching phenotype, than those of the wild-type62. Recent research showed that overexpression of JcTFL1b decreased shoot branching capacity in J. curcas 63, 64. Here, our results showed that the expressions of JcBEL1 (Cluster-26.17792) and JcTFL1b (Cluster-26.17723) in J. curcas were significantly decreased in the buds after GA3 or BA treatment (Fig. 3C and J), as in the activated axillary buds of hybrid aspen, where TFL1 ortholog CENL1 is down-regulated during axillary bud activation65, suggesting that down-regulation of JcBEL1 and JcTFL1b was correlated with bud outgrowth in J. curcas. Dormancy-associated protein1 (DRM1) is associated with bud para-dormancy and is routinely used as a marker for bud burst37, 66. An inverse correlation between the expression level of DRM1 and bud outgrowth was also found in many other plants, such as Arabidopsis 51, kiwifruit66, pea67 and sorghum62. Our results showed that GA3 or BA treatment of the axillary bud significantly decreased the expression levels of JcDRM1 (Cluster-26.5833) and JcDRM1-LIKE (JcDRML, Cluster-26.12832) (Fig. 3B and E and Table S5). The strong inverse correlation between the JcDRM1 and JcDRML expression levels and bud outgrowth indicated that these genes could be involved in the regulation of bud dormancy in J. curcas; nevertheless, the precise regulatory function of the JcDRM1 and JcDRML remains unclear.

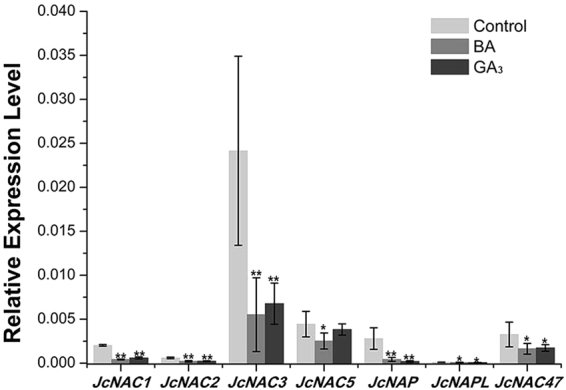

GA3, BA and SL antagonistically regulate NAM/ATAF1/CUC2 (NAC) family genes

NAC family genes are plant-specific and involved in many types of developmental, morphogenic and biotic or abiotic systems68–70. The NAC gene family has many members; however, only a few of these genes have been well characterized. Several NAC genes have been studied for their crucial role in the shoot apical meristem and floral organs71–75. Other developmental processes have also been shown to involve the NAC genes, such as axillary root development76, cell division77, embryogenesis78, programmed cell death (PCD)79, 80 and secondary cell wall formation81. In J. curcas, approximately 100 NAC genes were previously identified82. The results of the present study showed that a group of NAC genes, including JcNAC1 (Cluster-26.19073), JcNAC2 (Cluster-26.5606), JcNAC3 (Cluster-26.6331), JcNAC5 (Cluster-26.20575), JcNAC47 (Cluster-26.19991), JcNAP (Cluster-26.21633) and JcNAPL (Cluster-26.1094), were down-regulated by both GA3 and BA treatment among the 250 co-regulated genes (Fig. 5 and Table S5). Considering the biological functions of the NAC genes in the regulation of shoot apical meristem and axillary meristem development, we hypothesized that these co-regulated NAC genes were involved in the regulation of bud outgrowth by GA3 or CK in J. curcas.

Figure 5.

Quantitative real-time PCR analysis of a group of NAC genes negatively regulated by both GA3 and BA treatment. Cluster IDs: JcNAC1, Cluster-26.19073; JcNAC2, Cluster-26.5606; JcNAC3, Cluster-26.6331; JcNAC5, Cluster-26.20575; JcNAP, Cluster-26.21633; JcNAPL, Cluster-26.1094; JcNAC47, Cluster-26.19991. GAPDH was used as the internal reference. The error bars represent SE (n = 3). Student’s t-test was used to determine significant differences between the indicated and control groups. Significance levels: *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01.

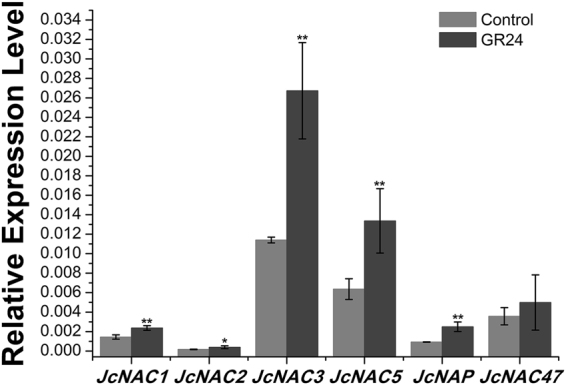

SLs are inhibitors of axillary bud outgrowth in pea10, 11 and J. curcas 19. Intriguingly, in J. curcas, GR24 (a synthetic analog of SL) treatment significantly up-regulated the expression of NAC genes, in contrast to the regulation by GA3 or BA (Fig. 6). This contrasting regulation of NAC genes is consistent with the physiological results showing that SL inhibited the bud outgrowth promoted by GA3 or BA treatment19, which further suggested that these co-regulated NAC genes may be involved in the regulation of bud outgrowth in response to phytohormones.

Figure 6.

SL up-regulates the expression of a group of NAC genes at the axillary buds at 12 h. Cluster IDs: JcNAC1, Cluster-26.19073; JcNAC2, Cluster-26.5606; JcNAC3, Cluster-26.6331; JcNAC5, Cluster-26.20575; JcNAP, Cluster-26.21633; JcNAC47, Cluster-26.19991. GAPDH was used as the internal reference. The error bars represent SE (n = 3). Student’s t-test was used to determine significant differences between the indicated and control groups. Significance levels: *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01.

BA regulates GA biosynthesis, catabolism and signaling genes in the buds

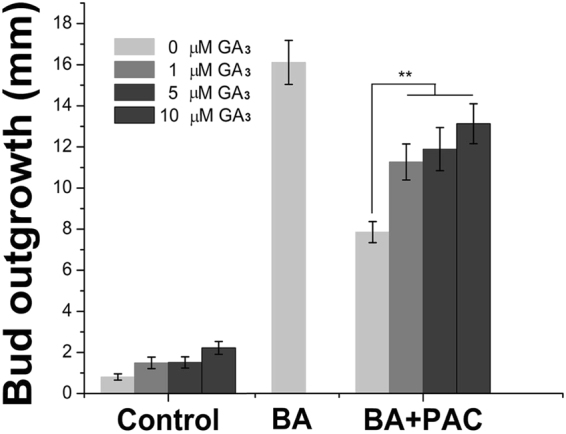

In the previous study19, we demonstrated that GA3 was required for the promotion of bud outgrowth by BA, and GA3 and CK synergistically regulate the axillary bud outgrowth in J. curcas. In this study, we found that addition of GA3 significantly reduced the inhibition of bud outgrowth by the paclobutrazol (PAC), an inhibitor of GA biosynthesis, in the BA + PAC combined treatment (Fig. 7), demonstrating that GA3 was directly involved in the promotion of bud outgrowth by CK.

Figure 7.

GA3 decreases the PAC inhibition of bud outgrowth induced by BA treatment. Low concentrations of GA3 (1, 5 and 10 μM) were co-applied with the BA + PAC solution (200 μM each). The error bars represent SE (n > 20). Student’s t-test was used to determine the significant differences between the indicated and control groups. Significance levels: **P < 0.01.

The concentration of bioactive GAs is regulated by the expression of genes encoding GA 20-oxidases (GA20ox) and GA 3-oxidases (GA3ox), responsible for the late steps of GA biosynthesis, as well as GA 2-oxidases (GA2ox), responsible for GA degradation83, 84. The transcriptome analysis showed that BA significantly increased the expression of JcGA20ox2 (Cluster-26.16883), and down-regulated the expression of JcGA2ox2 (Cluster-26.9482) and JcGA2ox4 (Cluster-26.18818) (Table S5), indicating that BA could promote GA biosynthesis and inhibit GA degradation in the buds of J. curcas.

We further analyzed the expression patterns of whole gene families involved in GA biosynthesis (principally JcGA20oxs and JcGA3oxs) and degradation (JcGA2oxs) using qPCR in the young axillary buds after BA treatment. Based on J. curcas genome sequences30, 31, we identified two JcGA20ox, three JcGA3ox, and five JcGA2ox gene members. The qPCR analysis revealed that the expressions of JcGA20ox and JcGA3ox1, which is the major member of JcGA3ox gene family expressed in the young axillary buds, were up-regulated after BA treatment; while all five members of JcGA2ox family were substantially down-regulated (Fig. 4), consistent with the transcriptome analysis results (Table S5). These results demonstrated that, at least in the young axillary buds, CK can promote GA accumulation and cooperatively regulate bud outgrowth. And the fact that BA had a relatively stronger effect on the promotion of axillary bud outgrowth19 likely reflects the combined effects of BA itself and the increased endogenous GA level induced by BA, rather than the effect of BA alone. This is in contrast with the results in Arabidopsis, where CK promotes GA degradation by inducing the GA deactivation gene AtGA2ox2 expression85.

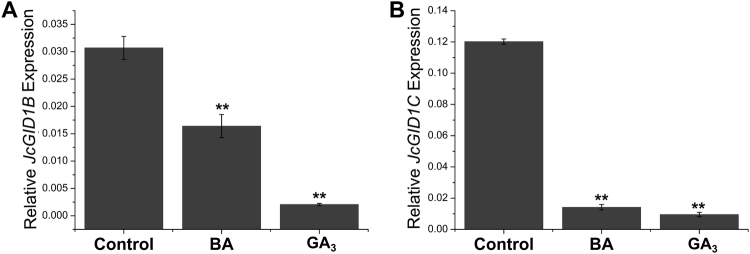

In addition, two genes encoding GA receptors, JcGID1B (Cluster-26.2964) and JcGID1C (Cluster-26.6734), were significantly down-regulated after BA or GA3 treatment in the buds (Fig. 8 and Table S5). Since BA treatment promoted GA biosynthesis and inhibited GA degradation in the buds, the down-regulation of GA receptors JcGID1s expression in response to both BA and GA3 treatment likely reflects the feedback regulation of GA signaling as shown in Arabidopsis 86. Similarly, GA biosynthesis genes (GA20oxs and GA3oxs) were significantly down-regulated, while GA degradation genes JcGA2ox2 and JcGA2ox4 were up-regulated after GA3 treatment (Fig. S4 and Table S5), indicating exogenously applied GA3 inhibited endogenous GA biosynthesis in J. curcas, which is consistent with observations in other plants87.

Figure 8.

BA or GA3 treatment inhibits the expression of GA receptor genes, JcGID1B (A, Cluster-26.2964) and JcGID1C (B, Cluster-26.6734). GAPDH was used as the internal reference. The error bars represent SE (n = 3). Student’s t-test was used to determine the significant differences between the indicated and control groups. Significance levels: **P < 0.01.

On the other hand, the transcriptome analysis showed that GA3 significantly down-regulated the expression of adenosine phosphate isopentenyl transferase 3 (JcIPT3, Cluster-2015.0) and Lonely Guy 1 (JcLOG1, Cluster-26.20104) (Table S3), both of which encode key enzymes involved in CK biosynthesis88. This result was consistent with a previous study showing that GA3 negatively regulated CK biosynthesis at the young axillary buds via inhibition of IPT family genes19, suggesting that the bud outgrowth induced by GA3 treatment is not through regulation of CK biosynthesis in the young axillary buds.

It is noteworthy that the GA3, one of the bioactive GAs, was used to study the transcriptome response of young axillary buds to GA in J. curcas in this report. However, Rinne et al. found that GA4 induced canonical bud burst and development in a concentration-dependent way, while GA3 failed to induce the same response in Populus 48. And Eriksson et al. found that GA4 is the active GA in the regulation of Arabidopsis floral initiation89. Therefore, further studies will be needed to identify which GAs are responsible for the regulation of shoot branching in J. curcas, although gibberellins GA3, GA4, and GA4+7 were all similar in their ability to stimulate branching from lateral buds in sweet cherry20.

Conclusion

Phytohormones are the major determinants in controlling axillary bud outgrowth. The identification of the hormone-responsive genes that are associated with bud dormancy and outgrowth could provide insight into the regulation of axillary bud growth. RNA-seq transcriptome expression analysis was used to elucidate the mechanisms underlying bud outgrowth control and identify the potential genes involved in the regulation of bud outgrowth. Both BA and GA3 could directly promote bud outgrowth in J. curcas. To further elucidate how the axillary bud responds to hormones and regulatory pathways in J. curcas, we identified the DEGs after GA3 or BA treatment using transcriptome sequencing. Overall, 250 DEGs (fold-change ≥ 2, FDR < 0.05) were co-regulated in response to GA3 or BA treatment and also exhibited similar expression patterns. These results suggested that GA3 and BA synergistically regulated axillary bud outgrowth in J. curcas, which is consistent with the physiological results. Moreover, BA treatment may promote GA accumulation in the young axillary buds as a result of the up-regulation of GA biosynthesis genes and the down-regulation of GA degradation genes in the axillary bud. This study helped to elucidate the cooperative relationship between these two hormones in regulating axillary bud outgrowth in J. curcas.

Materials and Methods

Plant materials and growth conditions

The J. curcas cultivar ‘Flowery’ was used in all experiments. Seedlings were planted in plastic growth pots (300 mL) under long-day photoperiod (14 h light/10 h dark). The growth temperature was 25 °C, and the light intensity was approximately 100 mol m−2 s−1. Twenty pots were placed in a plastic pallet. The seedlings were irrigated every other day by directly adding 1 L of distilled water into the pallet and fertilized with 1/4 MS containing only macroelements and microelements every other week as previously reported19.

Hormone treatment

Initially, the hormones were prepared as stock solutions (20 mM) and stored at −20 °C. GA3 and BA were separately dissolved in water-free ethanol and 0.3 M NaOH. The working solutions were prepared using the stock solutions. Each working solution (mock, GA3 and BA) contained the same concentrations of ethanol, NaOH and Tween-20 as reported previously19. Paclobutrazol (PAC) and GR24 were separately dissolved in methanol and acetone to obtain a stock solution of 10 mM, and then diluted with water to the final working concentrations. Controls were treated with distilled water containing the same concentrations of methanol or acetone and Tween-20 as reported previously19. For hormone treatments, 20 μL of the working solutions was directly dropped onto the leaf axil at node 1 of the three-week-old J. curcas seedlings. Twelve hours after hormone treatment, the node stem (approximately 10–20 mg, 3–4 mm by length) at node 1, where the axillary bud located, was sliced and immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen for RNA isolation and transcriptome sequencing analysis.

RNA isolation and sequencing

For each treatment, three biological replicates were prepared from a pool of axillary buds from approximately 20 three-week-old Jatropha seedlings. RNA isolation was performed using the Biozol Plant RNA Extraction Kit, as previously described19. RNA quantity and quality were assessed using a NanoDrop 2000c Spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific, Wilmington, DE, USA) and agarose gel electrophoresis, respectively. The RNA samples were further assessed using the Agilent Bioanalyzer 2100 system (Agilent Technologies, CA, USA). The mRNA was enriched from total RNA using oligo (dT) magnetic beads and fragmented into approximately 200-bp fragments. The cDNA was synthesized using a random hexamer primer and purified with magnetic beads. After the end reparation and 3′-end single nucleotide acid addition, the adaptors were ligated to the fragments. The fragments were enriched through PCR amplification and purified using magnetic beads. The libraries were assessed using the Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer and quantified using the ABI StepOnePlus Real-Time PCR System. The samples were sequenced with single-end on an Illumina HiSeqTM 2000 (BGI Tech, Shenzhen, China).

De novo assembly of transcriptome and abundance estimation

Low-quality reads with Phred scores < 20 were trimmed using Fastq_clean90, and the data quality was assessed using FASTQC91. The filtered reads were assembled using Trinity (version 2.0.6) with default parameters92, 93. The filtered reads from each library were mapped to de novo assemblies using Bowtie version v1.1.1 by allowing two mismatches (-v 2 -m 10)94. The transcript abundance was estimated using Corset (version 1.03)95. The count data generated from Corset were processed using the edgeR package44. Transcripts with less than one count per million reads (CPM) for at least three libraries were removed, and the remaining data were used for the next analysis. A matrix was constructed using the single factor style. Effective library sizes were determined using the trimmed mean of M values (TMM) normalization method. The common dispersion and tag wise dispersion were estimated using the quantile-adjusted conditional maximum likelihood (qCML) method. A multidimensional scaling was performed through the “plotMDS.dge” function of the edgeR package44. The exact test was performed to compute the expression of genes between the treatment and mock groups. Raw P values were adjusted for multiple testing using a false discovery rate (FDR)96. Genes with an FDR ≤ 0.05 and fold change (FC) ≥ 2 were regarded as differentially expressed genes (DEGs). GO analysis of the DEGs and pathways were processed using the DAVID97 with a cutoff of P-value ≤ 0.01. Hierarchical clustering of the co-regulated genes listed in Table S5 was performed using the pheatmap R package (version 1.0.7)98.

Quantitative real time PCR analysis (qRT-PCR)

For each sample, 1 μg RNA was used for cDNA synthesis using the PrimeScript Kit (TaKaRa Biotechnology, Dalian, China). qPCR was performed using TaKaRa SYBR Premix Ex TaqTM II (TaKaRa Biotechnology, Dalian, China). Quantitative real-time PCR was performed on three independent biological replicates for each sample and three technical replicates, using the Roche Light Cycler 480II System (Roche, Swiss). The primers used in the qRT-PCR analysis are listed in Table S10.

Availability of supporting data

All RNA-seq data obtained in the present study are listed in GenBank under accession number SRP048608. The GenBank accession numbers of the DEGs described in the paper are listed in Table S11. The full length sequences of the DEGs by GA3 and BA treatment are listed in Table S12.

Electronic supplementary material

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Zhi-Yu Pu for assistance with the fieldwork. This work was financially supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China [31370595, 31500500, and 31670612]; the Program of Chinese Academy of Sciences (CAS) [ZSZC-014]; and the CAS 135 Program [XTBG-T02]. The authors gratefully acknowledge the Central Laboratory of the Xishuangbanna Tropical Botanical Garden for providing research facilities.

Author Contributions

Jun Ni and Zeng-Fu Xu designed the experiments. Jun Ni and Mei-Li Zhao performed the hormone treatment, sample collection and the following experiments. Jun Ni, Mao-Sheng Chen, Mei-Li Zhao, Bang-Zhen Pan, Yan-Bin Tao and Zeng-Fu Xu analyzed the data. Jun Ni and Zeng-Fu Xu wrote the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Jun Ni and Mei-Li Zhao contributed equally to this work.

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at doi:10.1038/s41598-017-11588-0

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Janssen BJ, Drummond RS, Snowden KC. Regulation of axillary shoot development. Current Opinion in Plant Biology. 2014;17:28–35. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2013.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rinne PL, Paul LK, Vahala J, Kangasjärvi J, van der Schoot C. Axillary buds are dwarfed shoots that tightly regulate GA pathway and GA-inducible 1, 3-β-glucanase genes during branching in hybrid aspen. Journal of Experimental Botany. 2016;67:5975–5991. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erw352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Considine MJ, Considine JA. On the language and physiology of dormancy and quiescence in plants. Journal of Experimental Botany. 2016;67:3189–3203. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erw138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rameau C, et al. Multiple pathways regulate shoot branching. Frontiers in plant science. 2015;5:741. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2014.00741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Leduc N, et al. Light Signaling in Bud Outgrowth and Branching in Plants. Plants (Basel) 2014;3:223–250. doi: 10.3390/plants3020223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mason MG, Ross JJ, Babst BA, Wienclaw BN, Beveridge CA. Sugar demand, not auxin, is the initial regulator of apical dominance. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2014;111:6092–6097. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1322045111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Domagalska MA, Leyser O. Signal integration in the control of shoot branching. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2011;12:211–221. doi: 10.1038/nrm3088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vanstraelen M, Benková E. Hormonal interactions in the regulation of plant development. Annual Review of Cell & Developmental Biology. 2012;28:463–487. doi: 10.1146/annurev-cellbio-101011-155741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mueller D, Leyser O. Auxin, cytokinin and the control of shoot branching. Ann. Bot. 2011;107:1203–1212. doi: 10.1093/aob/mcr069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Umehara, M. et al. Inhibition of shoot branching by new terpenoid plant hormones. Nature455, 195–200, http://www.nature.com/nature/journal/v455/n7210/suppinfo/nature07272_S1.html (2008). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Gomez-Roldan V, et al. Strigolactone inhibition of shoot branching. Nature. 2008;455:189–194. doi: 10.1038/nature07271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Braun N, et al. The pea TCP transcription factor PsBRC1 acts downstream of strigolactones to control shoot branching. Plant Physiology. 2012;158:225–238. doi: 10.1104/pp.111.182725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Minakuchi K, et al. FINE CULM1 (FC1) works downstream of strigolactones to inhibit the outgrowth of axillary buds in rice. Plant and Cell Physiology. 2010;51:1127–1135. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcq083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Aguilar-Martínez JA, Poza-Carrión C, Cubas P. Arabidopsis BRANCHED1 acts as an integrator of branching signals within axillary buds. Plant Cell. 2007;19:458–472. doi: 10.1105/tpc.106.048934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brewer PB, Dun EA, Ferguson BJ, Rameau C, Beveridge CA. Strigolactone acts downstream of auxin to regulate bud outgrowth in pea and Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2009;150:482–493. doi: 10.1104/pp.108.134783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dun EA, de Saint Germain A, Rameau C, Beveridge CA. Antagonistic action of strigolactone and cytokinin in bud outgrowth control. Plant Physiology. 2012;158:487–498. doi: 10.1104/pp.111.186783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tetsuo O, Masaji K, Kiyohide K, Hitoshi Y, Motoshige K. A role of OsGA20ox1, encoding an isoform of gibberellin 20-oxidase, for regulation of plant stature in rice. Plant Molecular Biology. 2004;55:687–700. doi: 10.1007/s11103-004-1692-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Silverstone AL, et al. Repressing a repressor: gibberellin-induced rapid reduction of the RGA protein in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2001;13:1555–1566. doi: 10.1105/tpc.13.7.1555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ni J, et al. Gibberellin promotes shoot branching in the perennial woody plant Jatropha curcas. Plant Cell Physiol. 2015;56:1655–1666. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcv089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Elfving DC, Visser DB, Henry JL. Gibberellins stimulate lateral branch development in young sweet cherry trees in the orchard. International Journal of Fruit Science. 2011;11:41–54. doi: 10.1080/15538362.2011.554066. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jiang H, et al. Global analysis of gene expression profiles in developing physic nut (Jatropha curcas L.) Seeds. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e36522. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0036522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Qu, J. et al. Development of marker-free transgenic Jatropha plants with increased levels of seed oleic acid. Biotechnol. Biofuels5, 10.1186/1754-6834-5-10 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 23.Pamidimarri DS, Singh S, Mastan SG, Patel J, Reddy MP. Molecular characterization and identification of markers for toxic and non-toxic varieties of Jatropha curcas L. using RAPD, AFLP and SSR markers. Molecular Biology Reports. 2009;36:1357–1364. doi: 10.1007/s11033-008-9320-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Makkar H, Aderibigbe A, Becker K. Comparative evaluation of non-toxic and toxic varieties of Jatropha curcas for chemical composition, digestibility, protein degradability and toxic factors. Food Chemistry. 1998;62:207–215. doi: 10.1016/S0308-8146(97)00183-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pan B-Z, Xu Z-F. Benzyladenine treatment significantly increases the seed yield of the biofuel plant Jatropha curcas. Journal of Plant Growth Regulation. 2011;30:166–174. doi: 10.1007/s00344-010-9179-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhang F-L, et al. A novel betaine aldehyde dehydrogenase gene from Jatropha curcas, encoding an enzyme implicated in adaptation to environmental stress. Plant Science. 2008;174:510–518. doi: 10.1016/j.plantsci.2008.01.018. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Silva END, Ribeiro RV, Ferreira-Silva SL, Viégas RA, Silveira JAG. Salt stress induced damages on the photosynthesis of physic nut young plants. Scientia Agricola. 2011;68:62–68. doi: 10.1590/S0103-90162011000100010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Silva EN, Ferreira-Silva SL, Viégas RA, Silveira JAG. The role of organic and inorganic solutes in the osmotic adjustment of drought-stressed Jatropha curcas plants. Environmental and Experimental Botany. 2010;69:279–285. doi: 10.1016/j.envexpbot.2010.05.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ao P-X, Li Z-G, Gong M. Involvement of compatible solutes in chill hardening-induced chilling tolerance in Jatropha curcas seedlings. Acta Physiologiae Plantarum. 2013;35:3457–3464. doi: 10.1007/s11738-013-1381-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sato S, et al. Sequence analysis of the genome of an oil-bearing tree, Jatropha curcas L. DNA research. 2011;18:65–76. doi: 10.1093/dnares/dsq030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wu P, et al. Integrated genome sequence and linkage map of physic nut (Jatropha curcas L.), a biodiesel plant. Plant Journal. 2015;81:810–821. doi: 10.1111/tpj.12761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pan B-Z, Chen M-S, Ni J, Xu Z-F. Transcriptome of the inflorescence meristems of the biofuel plant Jatropha curcas treated with cytokinin. BMC genomics. 2014;15:974. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-15-974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chen M-S, et al. Analysis of the transcriptional responses in inflorescence buds of Jatropha curcas exposed to cytokinin treatment. BMC plant biology. 2014;14:318. doi: 10.1186/s12870-014-0318-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang H, Zou Z, Wang S, Gong M. Global analysis of transcriptome responses and gene expression profiles to cold stress of Jatropha curcas L. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e82817. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0082817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chen M-S, et al. Analysis of expressed sequence tags from biodiesel plant Jatropha curcas embryos at different developmental stages. Plant Science. 2011;181:696–700. doi: 10.1016/j.plantsci.2011.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Abdelgadir H, Johnson S, Van Staden J. Promoting branching of a potential biofuel crop Jatropha curcas L. by foliar application of plant growth regulators. Plant Growth Regul. 2009;58:287–295. doi: 10.1007/s10725-009-9377-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.José Antonio AM, César PC, Pilar C. Arabidopsis BRANCHED1 acts as an integrator of branching signals within axillary buds. Plant Cell. 2007;19:458–472. doi: 10.1105/tpc.106.048934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Stirnberg P, Furner IJ. & Ottoline Leyser, H. MAX2 participates in an SCF complex which acts locally at the node to suppress shoot branching. Plant J. 2007;50:80–94. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2007.03032.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Stirnberg P, van De Sande K, Leyser HO. MAX1 and MAX2 control shoot lateral branching in Arabidopsis. Development. 2002;129:1131–1141. doi: 10.1242/dev.129.5.1131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Soundappan I, et al. SMAX1-LIKE/D53 family members enable distinct MAX2-dependent responses to strigolactones and karrikins in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2015;27:3143–3159. doi: 10.1105/tpc.15.00562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jiang L, et al. DWARF 53 acts as a repressor of strigolactone signalling in rice. Nature. 2013;504:401–405. doi: 10.1038/nature12870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhou F, et al. D14-SCF(D3)-dependent degradation of D53 regulates strigolactone signalling. Nature. 2013;504:406–410. doi: 10.1038/nature12878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wang Z, Gerstein M, Snyder M. RNA-Seq: a revolutionary tool for transcriptomics. Nature Reviews Genetics. 2009;10:57–63. doi: 10.1038/nrg2484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Robinson MD, McCarthy DJ, Smyth G. K. edgeR: a Bioconductor package for differential expression analysis of digital gene expression data. Bioinformatics. 2010;26:139–140. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Albrecht T, Argueso CT. Should I fight or should I grow now? The role of cytokinins in plant growth and immunity and in the growth–defence trade-off. Annals of Botany. 2017;119:725–735. doi: 10.1093/aob/mcw211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nguyen HC, et al. Special trends in CBF and DREB2 groups in Eucalyptus gunnii vs Eucalyptus grandis suggest that CBF are master players in the trade-off between growth and stress resistance. Physiologia Plantarum. 2017;159:445–467. doi: 10.1111/ppl.12529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Qu J, Kang SG, Hah C, Jang J-C. Molecular and cellular characterization of GA-stimulated transcripts GASA4 and GASA6 in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Science. 2016;246:1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.plantsci.2016.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rinne PLH, et al. Chilling of dormant buds hyperinduces FLOWERING LOCUS T and recruits GA-inducible 1,3-β-glucanases to reopen signal conduits and release dormancy in Populus. The Plant Cell. 2011;23:130–146. doi: 10.1105/tpc.110.081307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Devitt ML, Stafstrom JP. Cell-cycle regulation during growth-dormancy cycles in pea axillary buds. Plant Molecular Biology. 1995;29:255–265. doi: 10.1007/BF00043650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cline MG. Concepts and terminology of apical dominance. American Journal of Botany. 1997;84:1064–1069. doi: 10.2307/2446149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tatematsu K, Ward S, Leyser O, Kamiya Y, Nambara E. Identification of cis-elements that regulate gene expression during initiation of axillary bud outgrowth in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiology. 2005;138:757–766. doi: 10.1104/pp.104.057984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Méndez J, Stillman B. Chromatin association of human origin recognition complex, cdc6, and minichromosome maintenance proteins during the cell cycle: assembly of prereplication complexes in late mitosis. Molecular & Cellular Biology. 2000;20:8602–8612. doi: 10.1128/MCB.20.22.8602-8612.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Coleman TR, Carpenter PB, Dunphy WG. The Xenopus Cdc6 protein is essential for the initiation of a single round of DNA replication in cell-free extracts. Cell. 1996;87:53–63. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81322-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Piatti S, Lengauer C, Nasmyth K. Cdc6 is an unstable protein whose de novo synthesis in G1 is important for the onset of S phase and for preventing a ‘reductional’ anaphase in the budding yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Embo Journal. 1995;14:3788–3799. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb00048.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Cocker JH, Piatti S, Santocanale C, Nasmyth K, Diffley J. An essential role for the Cdc6 protein in forming the pre-replicative complexes of budding yeast. Nature. 1996;379:180–182. doi: 10.1038/379180a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Shultz RW, Tatineni VM, Linda HB, Thompson WF. Genome-wide analysis of the core DNA replication machinery in the higher plants Arabidopsis and rice. Plant Physiology. 2007;144:1697–1714. doi: 10.1104/pp.107.101105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Rebecca S, et al. A CDC45 homolog in Arabidopsis is essential for meiosis, as shown by RNA interference-induced gene silencing. Plant Cell. 2004;16:99–113. doi: 10.1105/tpc.016865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.González-Plaza, J. J. et al. Transcriptomic analysis using olive varieties and breeding progenies identifies candidate genes involved in plant architecture. Frontiers in plant science7, 10.3389/fpls.2016.00240 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 59.Horiguchi G, Kim G-T, Tsukaya H. The transcription factor AtGRF5 and the transcription coactivator AN3 regulate cell proliferation in leaf primordia of Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Journal. 2005;43:68–78. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2005.02429.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Baumann K, et al. Changing the spatial pattern of TFL1 expression reveals its key role in the shoot meristem in controlling Arabidopsis flowering architecture. Journal of Experimental Botany. 2015;66:4769–4780. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erv247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Brambilla V, et al. Genetic and molecular interactions between BELL1 and MADS box factors support ovule development in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2007;19:2544–2556. doi: 10.1105/tpc.107.051797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kebrom TH, Mullet JE. Transcriptome Profiling of Tiller Buds Provides New Insights into PhyB Regulation of Tillering and Indeterminate Growth in Sorghum. Plant Physiology. 2016;170:2232–2250. doi: 10.1104/pp.16.00014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Li C, Luo L, Fu Q, Niu L, Xu Z-F. Identification and Characterization of the FT/TFL1 Gene Family in the Biofuel Plant Jatropha curcas. Plant Mol Biol Rep. 2015;33:326–333. doi: 10.1007/s11105-014-0747-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Li, C. Three TFL1 homologues regulate floral initiation in the biofuel plant Jatropha curcas. Scientific Reports7, 10.1038/srep43090 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 65.Rinne PLH, et al. Long and short photoperiod buds in hybrid aspen share structural development and expression patterns of marker genes. Journal of Experimental Botany. 2015;66:6745–6760. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erv380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Wood M, et al. Actinidia DRM1 - An intrinsically disordered protein whose mRNA expression Is inversely correlated with spring budbreak in kiwifruit. Plos One. 2013;8:e57354. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0057354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Stafstrom JP, Ripley BD, Devitt ML, Drake B. Dormancy-associated gene expression in pea axillary buds. Planta. 1998;205:547–552. doi: 10.1007/s004250050354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Ooka H, et al. Comprehensive analysis of NAC family genes in Oryza sativa and Arabidopsis thaliana. DNA Research. 2003;10:239–247. doi: 10.1093/dnares/10.6.239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Olsen AN, Ernst HA, Lo Leggio L, Skriver K. NAC transcription factors: structurally distinct, functionally diverse. Trends Plant Sci. 2005;10:79–87. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2004.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Hu W, et al. Genome-Wide Identification and Expression Analysis of the NAC Transcription Factor Family in Cassava. PLoS ONE. 2015;10:e0136993. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0136993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Souer E, vanHouwelingen A, Kloos D, Mol J, Koes R. The no apical meristem gene of petunia is required for pattern formation in embryos and flowers and is expressed at meristem and primordia boundaries. Cell. 1996;85:159–170. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81093-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Aida M, Ishida T, Fukaki H, Fujisawa H, Tasaka M. Genes involved in organ separation in Arabidopsis: An analysis of the cup-shaped cotyledon mutant. Plant Cell. 1997;9:841–857. doi: 10.1105/tpc.9.6.841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Sablowski RWM, Meyerowitz EM. A homolog of NO APICAL MERISTEM is an immediate target of the floral homeotic genes APETALA3/PISTILLATA. Cell. 1998;92:93–103. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80902-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Takada S, Hibara K, Ishida T, Tasaka M. The CUP-SHAPED COTYLEDON1 gene of Arabidopsis regulates shoot apical meristem formation. Development. 2001;128:1127–1135. doi: 10.1242/dev.128.7.1127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Vroemen CW, Mordhorst AP, Albrecht C, Kwaaitaal M, de Vries SC. The CUP-SHAPED COTYLEDON3 gene is required for boundary and shoot meristem formation in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2003;15:1563–1577. doi: 10.1105/tpc.012203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Xie Q, Frugis G, Colgan D, Chua NH. Arabidopsis NAC1 transduces auxin signal downstream of TIR1 to promote lateral root development. Genes Dev. 2000;14:3024–3036. doi: 10.1101/gad.852200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Kim YS, et al. A membrane-bound NAC transcription factor regulates cell division in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2006;18:3132–3144. doi: 10.1105/tpc.106.043018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Kunieda T, et al. NAC family proteins NARS1/NAC2 and NARS2/NAM in the outer integument regulate embryogenesis in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2008;20:2631–2642. doi: 10.1105/tpc.108.060160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Guo YF, Gan SS. AtNAP, a NAC family transcription factor, has an important role in leaf senescence. Plant Journal. 2006;46:601–612. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2006.02723.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Balazadeh S, et al. A gene regulatory network controlled by the NAC transcription factor ANAC092/AtNAC2/ORE1 during salt-promoted senescence. Plant Journal. 2010;62:250–264. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2010.04151.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Zhong RQ, Demura T, Ye ZH. SND1, a NAC domain transcription factor, is a key regulator of secondary wall synthesis in fibers of Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2006;18:3158–3170. doi: 10.1105/tpc.106.047399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Wu, Z. Y. et al. Genome-wide analysis of the NAC gene family in physic nut (Jatropha curcas L.). Plos One10, 10.1371/journal.pone.0131890 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 83.Peter H, Stephen GT. Gibberellin biosynthesis and its regulation. Biochemical Journal. 2012;444:11–25. doi: 10.1042/BJ20120245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Yamaguchi S. Gibberellin Metabolism and its Regulation. Annual Review of Plant Biology. 2008;59:225–251. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.59.032607.092804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Jasinski S, et al. KNOX action in Arabidopsis is mediated by coordinate regulation of cytokinin and gibberellin activities. Current Biology. 2005;15:1560–1565. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2005.07.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Griffiths J, et al. Genetic characterization and functional analysis of the GID1 gibberellin receptors in Arabidopsis. The Plant Cell. 2006;18:3399–3414. doi: 10.1105/tpc.106.047415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Yamaguchi S, Kamiya Y. Gibberellin Biosynthesis: Its Regulation by Endogenous and Environmental Signals. Plant and Cell Physiology. 2000;41:251–257. doi: 10.1093/pcp/41.3.251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Kieber, J. J. & Schaller, G. E. Cytokinins. The Arabidopsis Book, e0168, 10.1199/tab.0168 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 89.Eriksson S, Böhlenius H, Moritz T, Nilsson O. GA4 is the active gibberellin in the regulation of LEAFY transcription and Arabidopsis floral initiation. The Plant Cell Online. 2006;18:2172–2181. doi: 10.1105/tpc.106.042317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Zhang, M., Zhan, F., Sun, H. & Gong, X. Fastq_clean, An optimized pipeline to clean the Illumina sequencing data with quality control. IEEE International Conference on Bioinformatics and Biomedicine, 44-48, 10.1109/BIBM.2014.6999309 (2014).

- 91.Andrews, S. FQC: A quality control tool for high throughput sequence data. Reference Source (2010).

- 92.Haas BJ, et al. De novo transcript sequence reconstruction from RNA-seq using the Trinity platform for reference generation and analysis. Nature Protocols. 2013;8:1494–1512. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2013.084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Grabherr MG, et al. Full-length transcriptome assembly from RNA-Seq data without a reference genome. Nature Biotechnology. 2011;29:644–652. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Langmead B, Trapnell C, Pop M, Salzberg SL. Ultrafast and memory-efficient alignment of short DNA sequences to the human genome. Genome Biology. 2009;10:R25–R25. doi: 10.1186/gb-2009-10-3-r25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Davidson NM, Oshlack A. Corset: enabling differential gene expression analysis for de novo assembled transcriptomes. Genome Biology. 2014;15:410. doi: 10.1186/s13059-014-0410-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y. Controlling the false discovery rate - a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. B-Methodol. 1995;57:289–300. [Google Scholar]

- 97.Huang da W, Sherman BT, Lempicki RA. Systematic and integrative analysis of large gene lists using DAVID bioinformatics resources. Nature Protocols. 2009;4:44–57. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2008.211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Kolde, R. Pheatmap: Pretty Heatmaps, https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/pheatmap/index.html (2015).

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.