Abstract

It is unclear whether genetic markers interact with risk factors to influence atrial fibrillation (AF) risk. We performed genome-wide interaction analyses between genetic variants and age, sex, hypertension, and body mass index in the AFGen Consortium. Study-specific results were combined using meta-analysis (88,383 individuals of European descent, including 7,292 with AF). Variants with nominal interaction associations in the discovery analysis were tested for association in four independent studies (131,441 individuals, including 5,722 with AF). In the discovery analysis, the AF risk associated with the minor rs6817105 allele (at the PITX2 locus) was greater among subjects ≤ 65 years of age than among those > 65 years (interaction p-value = 4.0 × 10−5). The interaction p-value exceeded genome-wide significance in combined discovery and replication analyses (interaction p-value = 1.7 × 10−8). We observed one genome-wide significant interaction with body mass index and several suggestive interactions with age, sex, and body mass index in the discovery analysis. However, none was replicated in the independent sample. Our findings suggest that the pathogenesis of AF may differ according to age in individuals of European descent, but we did not observe evidence of statistically significant genetic interactions with sex, body mass index, or hypertension on AF risk.

Introduction

Atrial fibrillation (AF) is a common arrhythmia and is associated with increased risk for stroke, heart failure, and mortality1–4. Previous studies have demonstrated that increasing age, male sex, high blood pressure, and obesity are associated with higher AF risk5–11. AF is heritable12–17, and genetic association studies have identified 16 loci tagged by common genetic variants that are associated with AF18–22.

Typically, genome-wide association studies have assumed that the effect of each tested SNP on AF risk is constant across various risk factors, though some data suggest that the effect sizes may differ for different values of risk factors. For example, variants at the HIATL1 region have been shown to interact with alcohol consumption to affect colorectal cancer risk23. Understanding the differences in magnitudes of effect for SNPs in relation to AF across common clinical risk factors could potentially refine our knowledge about the genetic basis of AF in important clinical subsets of individuals. Nevertheless, no large systematic examination of interactions between genetic variants and clinical AF risk factors has been conducted.

We therefore aimed to determine whether common genetic variants interact with age, sex, hypertension, and body mass index to modify AF risk in a large sample of individuals of European ancestry.

Results

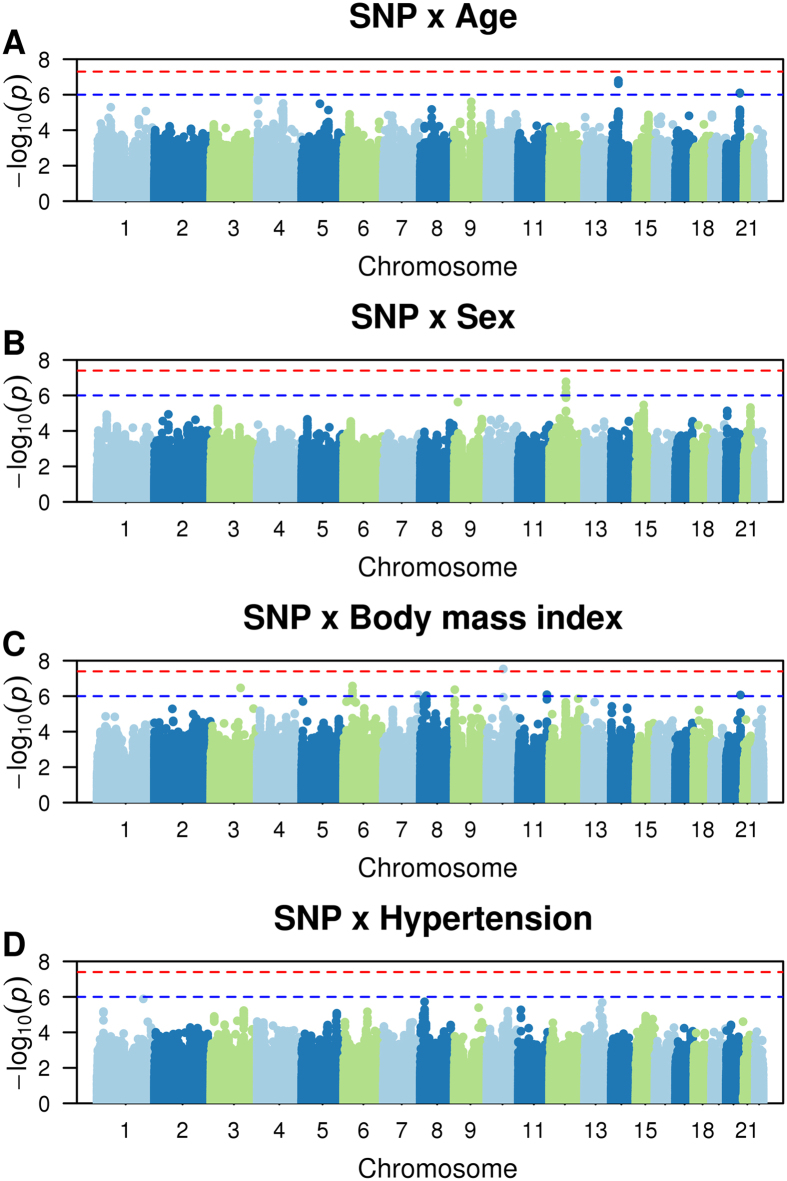

A total of 88,378 subjects, including 7,292 with AF, were included in the discovery analysis (Table 1). The numbers of included SNPs and values of genomic inflation factors (λ) for each study (after applying quality control criteria for SNP exclusions) are displayed in Supplemental Table 1. Overall, genomic inflation factors ranged from 0.85 to 1.2 across studies and interaction analyses. Quantile-quantile (QQ) plots of expected versus observed interaction p-value distributions for associations of the approximately 2.5 million autosomal SNPs for each interaction analysis are displayed in Supplemental Fig. 1a–d. Manhattan plots of -log10 (p-value) against the physical coordinates of the 22 autosomes are shown in Fig. 1A–D.

Table 1.

Subject Characteristics.

| N with AF | N total | Males, n (%) | Age, mean ± SD | Hypertension, n (%) | Body mass index, kg/m2, mean ± SD | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Discovery studies | ||||||

| Incident AF | ||||||

| AGES* | 158 | 2718 | 1011(37.2) | 76.3 ± 5.46 | 2144 (78.9) | 76.27 ± 5.46 |

| ARIC* | 799 | 9053 | 4255 (47.0) | 54.3 ± 5.7 | 2426 (26.8) | 27.0 ± 4.8 |

| CHS* | 763 | 3185 | 1234 (38.7) | 72.2 ± 5.3 | 1680 (52.8) | 26.3 ± 4.4 |

| FHS* | 306 | 4025 | 1751 (43.5) | 64.7 ± 12.6 | 1988 (49.5) | 27.7 ± 5.2 |

| MESA* | 155 | 2526 | 1206 (47.74) | 62.66 ± 10.24 | 975 (38.6) | 27.74 ± 5.06 |

| PREVEND* | 113 | 3520 | 1811 (50) | 49.5 ± 12.4 | 1157 (30) | 26.1 ± 4.3 |

| PROSPER* | 505 | 5244 | 2524 (48.1) | 75.34 ± 3.35 | 3257 (62.1) | 26.82 ± 4.18 |

| RS* | 591 | 5665 | 2282 (40.3) | 69.1 ± 8.98 | 3081 (54.4) | 26.32 ± 3.69 |

| WGHS* | 648 | 20842 | 0 (0) | 54.6 ± 7.0 | 5022 (24) | 25.3 ± 6.7 |

| Prevalent AF | ||||||

| AFNET/KORA | 448 | 886 | 524 (59.1) | 53.4 ± 7.8 | 326 (36.8) | 27.9 ± 4.6 |

| AGES | 241 | 2959 | 1154 (39.0) | 76.47 ± 5.50 | 2359 (79.8) | 27.06 ± 4.44 |

| BioVU o1 | 238 | 4766 | 2552 (53.6) | 62.2 ± 16.3 | 3270 (68.6) | 26.2 ± 11.2 |

| BioVU 660 | 120 | 3790 | 1722 (45.4) | 62.8 ± 15.9 | 1966 (51.9) | 24.0 ± 15.0 |

| CCAF | 807 | 2661 | 1918 (72.1) | 61.7 ± 11.15 | 1793 (67.4) | 29.5 ± 5.78 |

| FHS | 253 | 4401 | 1957 (44.5) | 65.4 ± 12.8 | 2215 (50.5) | 27.70 ± 5.16 |

| LURIC | 361 | 2959 | 2077 (70.2) | 63.0 ± 10.6 | 2154 (72.8) | 27.5 ± 4.02 |

| MGH/MIGEN | 366 | 1277 | 780 (61.1) | 49.5 ± 9.7 | — | — |

| RS | 309 | 5974 | 2427 (40.6) | 69.4 ± 9.1 | 3273 (54.8) | 26.3 ± 3.69 |

| SHIP | 107 | 1923 | 927 (48.2) | 50.97 ± 15.07 | 496 (25.8) | 27.33 ± 4.56 |

| Replication studies | ||||||

| Incident AF | ||||||

| MDCS | 876 | 7353 | 3800 (48) | 58.8 ± 6.6 | 5010 (68) | 26.1 ± 4.1 |

| Prevalent AF | ||||||

| BEAT-AF | 1520 | 3040 | 1795 (59) | 51.7 ± 18.6 | 1363 (45) | 25.8 ± 4.4 |

| FINCAVAS | 940 | 3021 | 1835 (61) | 61.9 ± 14 | 2117 (70) | 27.5 ± 4.5 |

| UK Biobank | 2386 | 118027 | 55669 (47) | 56.9 ± 7.9 | 25307 (21) | 27.5 ± 4.8 |

Abbreviations: AF: atrial fibrillation; NA: not available; SD: standard deviation. *Information at DNA collection.

Figure 1.

Manhattan plots of genetic interactions with age, sex, body mass index, and hypertension in relation to AF risk. The red line shows the significant interaction p-value threshold (p < 4 × 10−8), and the blue line shows the suggestive significant interaction p-value threshold (p < 1 × 10−6).

Interactions with risk factors at known AF loci

We first evaluated the associations between genetic interactions and clinical factors (age, sex, hypertension, and body mass index) with AF at 16 established AF susceptibility loci from prior genome-wide association studies (Supplemental Table 2; significance threshold = 6.25 × 10−4, see methods for explanation). We observed significant interactions with age for SNP rs6817105 (upstream of PITX2 at chromosome locus 4q25; interaction p-value = 4 × 10−5; Table 2). The minor C allele of SNP rs6817105 was associated with a greater risk for AF among individuals 65 years of age or younger [odds ratio (OR) = 1.75, 95% CI 1.61–1.91, p = 6.2 × 10−36], than among participants older than 65 years (OR = 1.38, 95% CI 1.28–1.47, p = 6.3 × 10−17). Among other known AF loci, SNP rs3807989 at the CAV1 locus displayed a nominal interaction with age that was not statistically significant (interaction p = 2.9 × 10−3; Table 2). However, the major G allele was associated with higher AF risk in the younger group (OR = 1.25, 95% CI 1.16–1.34, p = 3.6 × 10−10 for subjects ≤ 65 years; OR = 1.09, 95% CI 1.03–1.15, p = 1.4 × 10−3 for subjects >65). We did not observe any significant interactions between AF-associated SNPs and sex, hypertension, or body mass index.

Table 2.

Multiplicative SNP interactions with AF risk factors at known AF loci.

| SNP | A1/A2 | A1 freq | Loc | Closest gene | SNP and AF risk factor interaction | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | Sex | Body mass index | Hypertension | |||||||||

| Interaction β *(se) | p | Interaction β (se) | p | Interaction β (se) | p | Interaction β (se) | p | |||||

| rs6666258 | C/G | 0.30 | 1q21 | KCNN3 | 0.0979 (0.048) | 0.04 | 0.0092 (0.045) | 0.84 | −0.0023 (0.005) | 0.62 | 0.024 (0.045) | 0.60 |

| rs3903239 | G/A | 0.44 | 1q24 | PRRX1 | 0.0661 (0.044) | 0.13 | −0.050 (0.041) | 0.23 | 0.0021 (0.004) | 0.63 | −0.014 (0.041) | 0.74 |

| rs4642101 | G/T | 0.65 | 3p25 | CAND2 | 0.0828 (0.047) | 0.08 | 0.0425 (0.045) | 0.35 | −0.0024 (0.005) | 0.59 | 0.0813 (0.045) | 0.07 |

| rs1448818 | C/A | 0.25 | 4q25 | PITX2 | 0.0207 (0.049) | 0.67 | 0.0285 (0.046) | 0.54 | 0.0094 (0.005) | 0.04 | −0.0597 (0.045) | 0.19 |

| rs6817105 | C/T | 0.13 | 4q25 | PITX2 | 0.2420 (0.059) | 4.0 × 10−5 | 0.0065 (0.055) | 0.91 | 0.0078 (0.006) | 0.16 | −0.0516 (0.055) | 0.35 |

| rs4400058 | A/G | 0.09 | 4q25 | PITX2 | 0.0665 (0.070) | 0.34 | −0.0343 (0.068) | 0.61 | −0.0051 (0.007) | 0.47 | −0.0406 (0.066) | 0.54 |

| rs6838973 | C/T | 0.57 | 4q25 | PITX2 | 0.0636 (0.045) | 0.16 | −0.0599 (0.043) | 0.16 | −0.0005 (0.004) | 0.90 | −0.0823 (0.042) | 0.05 |

| rs13216675 | T/C | 0.69 | 6q22 | GJA1 | −0.0287 (0.050) | 0.57 | 0.0869 (0.047) | 0.07 | 0.0064 (0.005) | 0.18 | 0.0616 (0.046) | 0.18 |

| rs3807989 | G/A | 0.60 | 7q31 | CAV1 | 0.1329 (0.045) | 2.9 × 10−3 | −0.0054 (0.041) | 0.90 | −0.0003 (0.004) | 0.95 | −0.0603 (0.041) | 0.14 |

| rs10821415 | A/C | 0.42 | 9q22 | C9orf3 | 0.0736 (0.047) | 0.11 | −0.0039 (0.044) | 0.93 | 0.0012 (0.004) | 0.79 | −0.0813 (0.043) | 0.06 |

| rs10824026 | A/G | 0.84 | 10q22 | SYNPO2L | −0.0035 (0.063) | 0.96 | −0.0213 (0.059) | 0.72 | 0.0139 (0.006) | 0.02 | 0.258 (0.060) | 0.66 |

| rs12415501 | T/C | 0.16 | 10q24 | NEURL | 0.0701 (0.064) | 0.27 | 0.0994 (0.058) | 0.09 | 0.0011 (0.006) | 0.85 | 0.0684 (0.057) | 0.23 |

| rs10507248 | T/G | 0.73 | 12q24 | TBX5 | −0.0573 (0.050) | 0.25 | 0.0571 (0.046) | 0.22 | −0.0025 (0.005) | 0.59 | −0.0208 (0.046) | 0.65 |

| rs1152591 | A/G | 0.48 | 14q23 | SYNE2 | 0.0178 (0.045) | 0.69 | −0.0082 (0.042) | 0.85 | 0.004 (0.004) | 0.35 | 0.0255 (0.042) | 0.54 |

| rs7164883 | G/A | 0.16 | 15q24 | HCN4 | −0.0294 (0.058) | 0.61 | 0.0284 (0.054) | 0.60 | 0.0016 (0.006) | 0.78 | −0.0271 (0.055) | 0.62 |

| rs2106261 | T/C | 0.18 | 16q22 | ZFHX3 | 0.0106 (0.057) | 0.85 | 0.0434 (0.054) | 0.42 | −0.0021 (0.006) | 0.71 | 0.110 (0.053) | 0.04 |

The significance threshold 0.01/16 = 6.25 × 10−4. Abbreviations: AF: atrial fibrillation; A1: allele 1; the risk allele was defined based on a prior GWAS56; A2: allele 2; A1 freq: allele 1 frequency; Loc: locus; p: P-value for the interaction between the risk factor and the SNP.

*Interaction β was from regression using an additive model. Interaction β (se) was calculated as the meta-analysis log(effect) in subjects ≤ 65 years of age minus the meta-analysis log(effect) in subjects >65 years of age, or as the multiplicative interaction between SNP*risk factor for sex (females vs. males), hypertension (hypertensive vs. not), and body mass index (per 1 unit increment).

Interactions with risk factors in genome-wide analyses

Table 3 displays the results for SNP interactions with AF risk factors across the genome. The most significant genetic interaction that exceeded our genome-wide significance threshold (an interaction p-value < 4 × 10−8, see methods for explanation) was observed for SNP rs12416673 with body mass index (interaction p = 2.9 × 10−8; 6.4 kb upstream of COL13A1 at chromosome region 10q21; Table 3; Supplemental Figure 2). Specifically, with each 1-unit increase in body mass index, each copy of the minor A allele of SNP rs12416673 was associated with an increased risk for AF (interaction β = 0.0224, interaction p = 2.9 × 10−8). Additionally, we observed 8 loci that exhibited suggestive interactions with AF risk factors (i.e., the interaction p-value was < 1 × 10−6 for the top SNP, and two or more SNPs in the same region exhibited interaction p-values < 1 × 10−5). Specifically, we observed interactions with age at 2 loci, sex at 1 locus, and body mass index at 5 loci (Table 3). No genetic interactions with hypertension exceeded the suggestive genome-wide or adjusted AF susceptibility locus significance thresholds.

Table 3.

Discovery and replication analysis results of top SNP interactions with AF risk factors.

| SNP | Loc | Closest gene | A1/A2 | Discovery | Replication | Combined | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A1 freq (%) | Interaction β (se) | p | A1 freq (%) | Interaction β (se)* | p | A1 freq (%) | Interaction β (se)* | p | ||||

| SNP x Age | ||||||||||||

| rs6817105† | 4q25 | PITX2 | C/T | 0.13 | 0.2420 (0.059) | 4.0 × 10−5 | 0.11 | 0.2213 (0.067) | 9.5 × 10−4 | 0.12 | 0.2420 (0.043) | 1.7 × 10−8 |

| rs3807989† | 7q31 | CAV1 | G/A | 0.60 | 0.1329 (0.045) | 2.9 × 10−3 | 0.59 | −0.0531 (0.050) | 0.28 | 0.59 | 0.0325 (0.032) | 3.1 × 10−1 |

| rs2356251 | 14q22 | MAP4K5 | C/G | 0.06 | 0.5716 (0.109) | 1.6 × 10−7 | 0.04 | −0.1894 (0.123) | 0.12 | 0.05 | 0.2294 (0.081) | 4.5 × 10−3 |

| rs1572779 | 20q13 | MIR548AG2 | G/T | 0.10 | 0.3468 (0.070) | 7.9 × 10−7 | 0.09 | 0.1456 (0.090) | 0.10 | 0.10 | 0.2446 (0.054) | 5.7 × 10−6 |

| SNP x Sex | ||||||||||||

| rs2730668 | 12q21 | TRHDE | T/C | 0.76 | 0.2734 (0.052) | 1.7 × 10−7 | 0.76 | 0.0846 (0.0563) | 0.13 | 0.76 | 0.1860 (0.0383) | 1.2 × 10−6 |

| SNP x Body Mass Index | ||||||||||||

| rs9394492 | 6q21 | BTBD9 | T/C | 0.36 | 0.0222 (0.004) | 2.7 × 10−7 | 0.38 | −0.0070 (0.005) | 0.15 | 0.37 | 0.0092 (0.003) | 4.1 × 10−3 |

| rs1874425 | 8q21 | ADrA1A | T/C | 0.25 | 0.0231 (0.005) | 9.3 × 10−7 | 0.25 | 0.0070 (0.005) | 0.18 | 0.25 | 0.0160 (0.004) | 5.4 × 10−6 |

| rs1545567 | 9p24 | VLDLR | T/C | 0.64 | −0.0256 (0.005) | 4.3 × 10−7 | 0.65 | −0.0010 (0.005) | 0.85 | 0.65 | −0.0131 (0.004) | 2.3 × 10−4 |

| rs12416673 | 10q21 | COL13A1 | A/G | 0.43 | 0.0224 (0.004) | 2.9 × 10−8 | 0.43 | −0.0018 (0.005) | 0.71 | 0.43 | 0.0122 (0.003) | 7.1 × 10−5 |

| rs6062828 | 20q13 | LOC105372719/YTHDF1 | C/G | 0.68 | −0.0245 (0.005) | 8.6 × 10−7 | 0.69 | −0.0105 (0.005) | 0.03 | 0.69 | −0.0174 (0.004) | 6.5 × 10−7 |

Abbreviations: AF: atrial fibrillation; A1: allele 1; the risk allele was defined based on a prior GWAS56; A2: allele 2; A1 freq: allele 1 frequency; Loc: locus; p: P-value for the interaction between the risk factor and the SNP.

*Interaction β was from regression using additive model. Interaction β (se) was calculated as the meta-analysis log(effect) in subjects ≤ 65 years of age minus the meta-analysis log(effect) in subjects > 65 years of age, or as the multiplicative interaction between SNP* risk factor for sex (females vs. males) and body mass index (per 1 unit increment).

†Known AF loci.

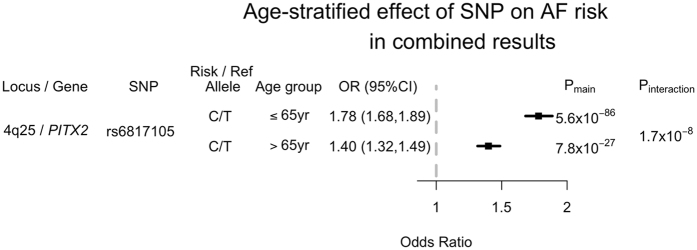

Replication

In total, we selected 10 SNP interactions (Table 3) for replication association testing in four independent cohorts (131,441 individuals, including 5,722 with AF). Only one interaction remained significantly associated with AF. SNP rs6817105 at the 4q25 locus exhibited a significant interaction with age (interaction p = 9.5 × 10−4). As in our discovery analysis, among individuals with the minor C allele of rs6817105, those ≤65 years old had a greater risk for AF (OR = 1.80; 95% CI 1.67–1.95, p = 6.6 × 10−52), than participants older than 65 years (OR = 1.45; 95% CI 1.30–1.61, p = 1.4 × 10−11). Similarly, rs6817105 was associated with a 27% higher AF risk in subjects ≤65 years of age (compared with subjects >65 years of age) in the combined discovery and replication analysis (interaction p = 1.7 × 10−8; Fig. 2). A greater risk of AF for the rs6817105 C allele was observed in participants aged 65 years or younger (OR = 1.78; 95% CI 1.68–1.89, p = 5.6 × 10−86) than in participants older than 65 years (OR = 1.40; 95% CI 1.32–1.49, p = 7.8 × 10−27).

Figure 2.

Age-stratified association between the chromosome 4q25 locus and AF in the combined dataset of primary and replication studies. OR and Pmain refer to the odds ratio and p-value for the association test between rs6817105 and AF risk in each age-stratum. Pinteraction refers to the p-value corresponding to the difference in effect sizes between the two age strata tested.

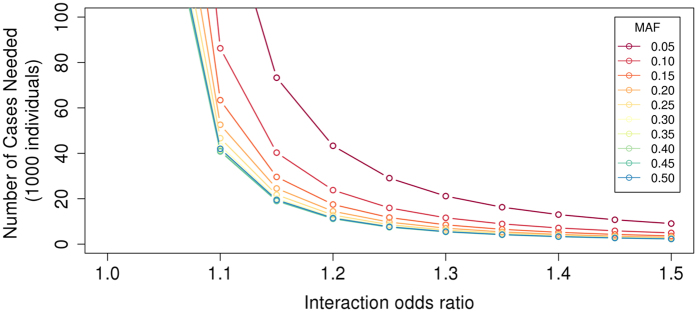

Power calculation

Given the lack of observed associations between SNP interactions with clinical risk factors and AF, we performed power calculations to estimate power for discovery using Quanto24 (http://biostats.usc.edu/Quanto.html; Fig. 3). As an example, we estimated power to observe a SNP interaction with sex, assuming a population comprised of 50% males, an AF population prevalence of 1%, and a case to control ratio of 1:10 (as in our study). We modeled a main effect OR of 1.5 for sex, and a genetic odds ratio of 1.5 for a SNP. We estimated that >100,000 AF cases would be a required to achieve 80% power for such an effect size, indicating that we had limited power to detect all but substantial genetic interactions with clinical risk factors.

Figure 3.

Number of cases required to detect interaction odds ratios between 1.01 to 1.5 with common SNPs (minor allele frequencies (MAF) of 0.05–0.5) with 80% power assuming an AF prevalence of 1%, 50% males, SNP marginal effect odds ratios of 1.5, sex marginal effect odds ratios of 1.5, case:control ratios of 1:10, and α = 4 × 10−8. Power calculations were performed using Quanto24.

Discussion

In our analysis of ~88,000 individuals of European ancestry, including 7,292 individuals with AF, we observed that the well-established AF locus at chromosome region 4q25 (tagged by rs6817105) was associated with a differential risk for AF according to age. Specifically, the OR for each copy of the minor rs6817105 allele was 1.78 for individuals ≤65 years of age, compared to 1.40 for individuals >65 years. Beyond the age interaction with the 4q25 locus, we did not observe any significant interactions between genetic variants and age, sex, hypertension, or body mass index after replication attempts. These findings suggest that strong genetic interactions with the AF risk factors studied in this manuscript are unlikely to be prominent mechanisms driving AF susceptibility.

Our findings support and extend prior studies examining genetic interactions for AF. For example, top variants at the 4q25 chromosome locus, upstream of PITX2, were associated with greater AF risks among younger individuals in secondary analyses of a genome-wide association study20. However, no formal statistical test of interaction was performed. Greater effect sizes of other AF susceptibility SNPs at the 4q25 locus were also observed among younger rather than older individuals in some, but not all, cohorts in a large replication study25. Moreover, in keeping with our observations, prior studies did not find evidence that AF risk is modified by interactions between SNPs at the 4q25 locus and sex20. Our findings demonstrate that genetic variation at the 4q25 locus is, on average, associated with greater risks for early-onset AF.

Our findings are consistent with epidemiologic observations demonstrating greater heritability for earlier onset of AF16. The stronger effect of the 4q25 locus on AF in a younger population implies that the contribution of this locus to AF susceptibility may be more relevant to those with early-onset AF, rather than later onset forms. Overall, our observation that genetic variation at the 4q25 locus is associated with AF (beyond genome-wide significant thresholds) in both younger and older individuals underscores the predominant role of this locus in AF pathogenesis–regardless of age.

PITX2 is a homeobox transcription factor involved in specification of pulmonary vasculature26, cardiac laterality27, and suppression of a left atrial sinoatrial-node like pacemaker28. Heterozygous null Pitx2c mouse hearts are more susceptible to pacing induced AF than are wild-type counterparts29. The relative roles of PITX2 regulation in AF susceptibility in both human development and in adult life are unclear. Future larger studies are warranted to systematically determine whether there are different age-specific etiologic subtypes of AF, and whether PITX2 modulation varies with age according to genotype.

Although our analysis was not designed to specifically quantify the contribution of genetic factors to AF heritability, the absence of observed interactions between AF and sex, body mass index, and hypertension suggests that common variant interactions with these clinical risk factors are unlikely to explain a substantial proportion of variance in AF susceptibility. Larger studies will be necessary to accurately quantify the contributions of both common and rare variation, epigenetic mechanisms, copy-number variation, epistatic effects, and other environmental interactions that may influence AF heritability. Moreover, further examination is needed to determine the extent to which the 4q25 locus, the predominant susceptibility locus for AF, explains the heritability of the condition.

Our study should be interpreted in the context of the study design. First, we included individuals of European ancestry only, so our finding may not be generalizable to other racial groups. Second, AF risk factors were available only at the time of AF onset in case-control studies, rather than before AF onset, potentially biasing toward the null any biologically relevant SNP by risk factor interactions that may occur years before the onset of AF. However, we suspect that such misclassification of risk factor status is unlikely to have resulted in systematic bias for body mass index (which tends to be relatively stable over time30) and age (because an interaction with age and the PITX2 locus is supported by prior observations). Third, our sample size provided limited power to identify interactions with relatively small effect sizes. Additionally, the use of more powerful statistical approaches31, non-multiplicative interactions, and inclusion of additional AF risk factors, may facilitate identification of loci at which genetic interactions exist in relation to AF. Fourth, our single SNP interaction approach does not exclude a lack of interaction with polygenic susceptibility to AF. Fifth, we acknowledge that AF may be clinically unrecognized, leading to misclassification of AF status, and that we lacked power to analyze AF subtypes separately. Future analyses with additional arrhythmia outcomes may help clarify the role of genetic interactions with risk factors across a range of arrhythmia phenotypes.

In summary, we identified a significant interaction with age at the AF susceptibility locus on chromosome 4q25 upstream of PITX2 in individuals of European ancestry. Despite several suggestive SNP interactions with common AF risk factors in discovery analyses, we did not observe substantial evidence for such interactions as common mechanisms underlying AF risk.

Methods

Study population

Discovery cohorts included the: German Competence Network for Atrial Fibrillation and Cooperative Health Research in the Region Augsburg (AFNET/KORA); Age, Gene/Environment Susceptibility Reykjavik Study (AGES) study; Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) study; Vanderbilt electronic medical record-linked DNA repository (BioVU); Cleveland Clinic Lone AF study (CCAF); Cardiovascular Health Study (CHS); Framingham Heart Study (FHS); Ludwigshafen Risk and Cardiovascular Health (LURIC) study; Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA); Massachusetts General Hospital Lone AF study and Myocardial Infarction Genetics Consortium (MGH/MIGEN); Prevention of Renal and Vascular End-stage Disease (PREVEND) study; PROspective Study of Pravastatin in the Elderly at Risk (PROSPER); Rotterdam Study (RS); Study of Health in Pomerania (SHIP); and Women’s Genome Health Study (WGHS). Replication studies included the: Basel Atrial Fibrillation Cohort Study (Beat-AF); Finnish Cardiovascular Study (FINCAVAS); Malmo diet and cancer study (MDCS); and UK Biobank. Detailed descriptions of each study have been previously reported (Supplemental Methods and Supplemental Table 3).

The study protocol was approved by the Ethical Committee/institutional review boards of Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich, National Bioethics Committee, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, University of Minnesota, Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Cleveland Clinic, University of Washington, Boston University Medical Campus, Rhineland-Palatinate State Chamber of Physicians, Massachusetts General Hospital, University Medical Center Groningen, Leiden University Medical Center, Erasmus MC - University Medical Center Rotterdam, University Medicine Greifswald, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, ethics committee northwest/central Switzerland, ethics committee Zurich, Pirkanmaa Hospital District, and Lund University. All MESA study sites received approval to conduct this research from local institutional review boards at: Columbia University (for the MESA New York Field Center), Johns Hopkins University (for the MESA Baltimore Field Center), Northwestern University (for the MESA Chicago Field Center), University of California, Los Angeles (for the MESA Los Angeles Field Center), University of Minnesota (for the MESA Twin Cities Field Center), Wake Forest University Health Sciences Center (for the MESA Winston-Salem Field Center). Written informed consent was obtained from all study subjects or their proxies (except BioVU, which is a de-identified EMR biorepository and was “opt-out” prior to December 2014). All experiments were performed in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations.

AF ascertainment

Ascertainment of AF and risk factors in each study has been described previously10, 14, 32–54, Detailed descriptions are provided in Supplemental Table 3. We defined prevalent AF as an event that was diagnosed at or prior to an individual’s DNA collection in cohort studies and on the basis of AF ascertainment in case-control studies. We defined incident AF as an event that was diagnosed after DNA collection among participants free of clinically apparent AF at DNA collection in cohort studies. All AF risk factors except age were ascertained at the time of DNA collection. Age was defined at DNA collection or at the date of recruitment in cohort studies, and at time of AF diagnosis (for AF cases) or at time of DNA collection (for controls) in case-control studies.

Exposure ascertainment

Sex was defined on the basis of self-report. Participants were classified as having hypertension if the systolic blood pressure was ≥140 mm Hg or the diastolic blood pressure was ≥90 mm Hg at any clinic visit or exam antecedent to DNA collection, or if the participant was receiving treatment with an antihypertensive medication and had a self-reported history of hypertension or high blood pressure at the time of DNA collection (not applicable in ARIC or FHS; Supplemental Table 3). Body mass index was defined as the weight (kg) divided by the height (m) squared. Blood pressure measurements, medication lists, weights, and heights were ascertained according to study-specific protocols. All participants in the discovery analysis were genotyped on genome-wide SNP array platforms (Supplemental Table 4). Imputed genotypes used in our analysis included approximately 2.5 million genetic variants from the HapMap CEU sample (release 22).

Statistical analysis

For each individual study, logistic regression (for prevalent AF; for incident AF in MESA and PREVEND only), generalized estimating equations (in FHS to account for related individuals), or Cox proportional hazard regression (for incident AF in prospective cohorts other than MESA and PREVEND) were performed to examine whether AF was associated with interactions between SNP and AF risk factors. For Cox models, person-time began at study baseline, and individuals were censored at death or loss to follow-up. Robust variance estimates were used when feasible. Details of the regression models are described in Supplemental Table 4. All models were adjusted for age (age at baseline for incident AF, and age at AF onset for prevalent AF), sex, site (ARIC and CHS), sub-cohort (FHS), study-specific covariates, and population structure, if applicable. SNPs with low imputation quality (R-square < 0.3) or a minor allele frequency < 0.05 were removed from the analysis.

For interaction analyses involving sex, hypertension, and body mass index, main effect terms for each risk factor, as well as multiplicative interaction terms between each SNP and the respective risk factor, were included in the regression models. Regarding analyses of age, nonlinear associations between SNPs and age could potentially go undetected, due to variable distributions of age across the studies in our analysis. Additionally, some studies had only or mostly early-onset/late-onset AF cases, which limited our ability to perform a regression model with dichotomized age in such samples. Therefore, we assessed SNP interactions with age by comparing meta-analysis estimates of associations between each SNP and AF in individuals ≤65 versus >65 years of age (see below). Studies with <100 AF events in each stratum of age were not included, in order to avoid unstable effect estimates.

Estimators for multiplicative interaction terms were meta-analyzed for sex, hypertension, and body mass index analyses in METAL55, using an inverse-variance weighted fixed-effects approach with genomic-control correction. For age, we performed an inverse-variance weighted fixed-effects meta-analysis of the estimators for each SNP separately within each age stratum, with genomic-control correction. Estimators were compared using a Z test, as mentioned above.

SNPs with absolute effect sizes ≥3 or SNPs that were available in only one study were excluded from our final results, to minimize the likelihood of spurious false positive findings. For each of the four genome-wide interaction assessments, we employed an experiment-wide two sided alpha threshold of 0.05, which we adjusted for multiple hypothesis testing. We distributed the alpha differentially across the genome, according to a priori hypotheses about interactions between SNPs and AF risk factors. Specifically, we distributed one-fifth of the alpha to each of the 16 most significantly associated SNPs at genome-wide significant loci identified in prior studies56, 57 (interaction p < 0.01/16 = 6.25 × 10−4). The remaining four-fifths of the alpha were distributed evenly across the genome, for an alpha threshold of 4 × 10−8 (interaction p < 0.04/~1,000,000 independent tests).

Significantly associated SNPs and SNPs with suggestive associations (i.e., an interaction p < 0.005 at a recognized AF GWAS locus; or an interaction p < 1 × 10−6 combined with interaction p < 1 × 10−5 for two additional SNPs within the same ±50 kb region) in the discovery analysis were carried forward for replication testing. In total, we carried forward 10 SNPs for replication testing (see below), and therefore assumed a replication interaction p threshold of 0.005 (0.05/10 SNPs). The results of replication studies alone, as well as combined with results from discovery studies, were meta-analyzed as described above.

Electronic supplementary material

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank all subjects, staffs, and investigators of participating studies. AFNET/KORA: This work is funded by the European Commision’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme (grant number 633196: CATCH ME to Dr. Sinner). AGES: The Age, Gene/Environment Susceptibility Reykjavik Study is funded by NIH contract N01-AG-12100. ARIC: The Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Study is carried out as a collaborative study supported by National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute contracts (HHSN268201100005C, HHSN268201100006C, HHSN268201100007C, HHSN268201100008C, HHSN268201100009C, HHSN268201100010C, HHSN268201100011C, and HHSN268201100012C), R01HL087641, R01HL59367 and R01HL086694; National Human Genome Research Institute contract U01HG004402; and National Institutes of Health contract HHSN268200625226C. The authors thank the staff and participants of the ARIC study for their important contributions. Infrastructure was partly supported by Grant Number UL1RR025005, a component of the National Institutes of Health and NIH Roadmap for Medical Research. This work was additionally supported by American Heart Association grant 16EIA26410001 (Alonso). BioVU: The dataset used in the analyses described were obtained from Vanderbilt University Medical Centers BioVU which is supported by institutional funding and by the Vanderbilt CTSA grant UL1 TR000445 from NCATS/NIH. Genome-wide genotyping was funded by NIH grants RC2GM092618 from NIGMS/OD and U01HG004603 from NHGRI/NIGMS. CCAF: R01 HL090620 and R01 HL111314 from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (Chung, Barnard, J. Smith, Van Wagoner); NIH/NCRR, CTSA 1UL-RR024989 (Chung, Van Wagoner); Heart and Vascular Institute, Department of Cardiovascular Medicine, Cleveland Clinic (Chung); Tomsich Atrial Fibrillation Research Fund (Chung); Leducq Foundation 07-CVD 03 (Van Wagoner, Chung); Atrial Fibrillation Innovation Center, State of Ohio (Van Wagoner, Chung). CHS: This Cardiovascular Health Study research was supported by NHLBI contracts HHSN268201200036C, HHSN268200800007C, N01HC55222, N01HC85079, N01HC85080, N01HC85081, N01HC85082, N01HC85083, N01HC85086; and NHLBI grants U01HL080295, R01HL087652, R01HL105756, R01HL103612, R01HL120393, and R01HL130114 with additional contribution from the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS). Additional support was provided through R01AG023629 from the National Institute on Aging (NIA). A full list of principal CHS investigators and institutions can be found at CHS-NHLBI.org. The provision of genotyping data was supported in part by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, CTSI grant UL1TR000124, and the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Disease Diabetes Research Center (DRC) grant DK063491 to the Southern California Diabetes Endocrinology Research Center. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Psaty serves on the DSMB of a clinical trial funded by Zoll LifeCor and on the Steering Committee of the Yale Open Data Access Project funded by Johnson & Johnson. FINCAVAS: The Finnish Cardiovascular Study (FINCAVAS) has been financially supported by the Competitive Research Funding of the Tampere University Hospital (Grant 9M048 and 9N035), the Finnish Cultural Foundation, the Finnish Foundation for Cardiovascular Research, the Emil Aaltonen Foundation, Finland, and the Tampere Tuberculosis Foundation. FHS: Funding for SHARe Affymetrix genotyping was provided by NHLBI Contract N02-HL-64278. SHARe Illumina genotyping was provided under an agreement between Illumina and Boston University. Funding support for the FHS through 1R01HL128914; 2R01 HL092577; HHSN268201500001I; N01-HC 25195; and Framingham Atrial Fibrillation/Flutter reviewed through 2012 dataset was provided by NHLBI grants 1R01HL092577, 1R01HL102214, 1RC1HL101056 and NINDS grant 6R01-NS-17950. LURIC: The Ludwigshafen Risk and Cardiovascular Health study was supported by the seventh framework program of the European commission (RiskyCAD, grant agreement number 305739). Support for genotyping was provided by the seventh framework program of the European commission (AtheroRemo, grant agreement number 201668). MESA: The Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis study was supported by NIH contracts HHSN2682015000031, N01-HC-95159, N01-HC-95160, N01-HC-95161, N01-HC-95162, N01-HC-95163, N01-HC-95164, N01-HC-95165, N01-HC-95166, N01-HC-95167, N01-HC-95168, N01-HC-95169 and by grants UL1-TR-000040, UL1-TR-001079, and UL1-RR-025005 from NCRR. Funding for MESA SHARe genotyping was provided by NHLBI Contract N02-HL-6-4278. The provision of genotyping data was supported in part by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, CTSI grant UL1TR000124, and the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Disease Diabetes Research Center (DRC) grant DK063491 to the Southern California Diabetes Endocrinology Research Center. PREVEND: The PREVEND study is supported by the Dutch Kidney Foundation (grant E0.13) and the Netherlands Heart Foundation (grant NHS2010B280). Dr. M. Rienstra is supported by grants from the Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research (Veni grant 016.136.055). PROSPER: The PROSPER study was supported by an investigator initiated grant obtained from Bristol-Myers Squibb. Prof. Dr. J. W. Jukema is an Established Clinical Investigator of the Netherlands Heart Foundation (grant 2001 D 032). Support for genotyping was provided by the seventh framework program of the European commission (grant 223004) and by the Netherlands Genomics Initiative (Netherlands Consortium for Healthy Aging grant 050-060-810). RS: The Rotterdam Study is supported by the Erasmus Medical Center and Erasmus University Rotterdam; the Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research; the Netherlands Organization for Health Research and Development (ZonMw); the Research Institute for Diseases in the Elderly; The Netherlands Heart Foundation; the Ministry of Education, Culture and Science; the Ministry of Health Welfare and Sports; the European Commission; and the Municipality of Rotterdam. Support for genotyping was provided by the Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research (NWO) (175.010.2005.011, 911.03.012) and Research Institute for Diseases in the Elderly (RIDE). Oscar H. Franco works in ErasmusAGE, a center for aging research across the life course funded by Nestlé Nutrition (Nestec Ltd.), Metagenics, Inc., and AXA. Nestlé Nutrition (Nestec Ltd.), Metagenics, Inc., and AXA had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; and preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript. SHIP: SHIP is part of the Community Medicine Research net of the University of Greifswald, Germany, which is funded by the Federal Ministry of Education and Research (grants no. 01ZZ9603, 01ZZ0103, and 01ZZ0403), the Ministry of Cultural Affairs as well as the Social Ministry of the Federal State of Mecklenburg-West Pomerania, and the network ‘Greifswald Approach to Individualized Medicine (GANI_MED)’ funded by the Federal Ministry of Education and Research (grant 03IS2061A). Genome-wide data have been supported by the Federal Ministry of Education and Research (grant no. 03ZIK012) and a joint grant from Siemens Healthcare, Erlangen, Germany and the Federal State of Mecklenburg- West Pomerania. The University of Greifswald is a member of the Caché Campus program of the InterSystems GmbH.

Author Contributions

L.-C.W. meta-analyzed the data and prepared all figures and tables. L.-C.W. and S.A.L. drafted the manuscript. L.-C.W., K.L.L., M.M.-N., A.V.S., S.T., P.E.W., J.B., J.C.B., L.-P.L., M.E.K., A.M., H.J.L., M.R., S.T., B.P.K., M.D., D.K., D.I.C., M.F.S., M.W., L.J.L., T.B.H., E.Z.S., A.A., G.P., P.L.T., J.C.D., M.B.S., D.R.V.W., J.D.S., B.M.P., N.S., K.D.T., M.K., K.N., G.E.D., O.M., G.E., J.Y., X.G., I.E.C., P.T.E., B.G., N.V., P.M., I.F., J.H., O.H.F., A.G.U., U.V., A.T., L.M.R., S.K., V.G., D.E.A., D.C., D.M.R., M.K.C., S.R.H., E.J.B., T.L., W.M., J.G.S., J.I.R., P.v.d.H., J.W.J., B.H.S., S.B.F., C.M.A., and S.A.L. participated in the analysis and/or interpretation of the results. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript. K.L.L., E.J.B., and S.A.L. supervised the study.

Competing Interests

This work was supported by grants from the NIH K23HL114724 (Lubitz), 1RO1HL092577 and R01HL128914 (Benjamin and Ellinor), K24HL105780 (Ellinor), Doris Duke Charitable Foundation Clinical Scientist Development Award 2014105 (Lubitz), an Established Investigator Award from the American Heart Association 13EIA14220013 (Ellinor), the Fondation Leducq 14CVD01 (Ellinor). Dr. Ellinor is the principal investigator on a grant from Bayer HealthCare to the Broad Institute focused on the genetics and therapeutics of atrial fibrillation. Dr. Christophersen is supported by a mobility grant from the Research Council of Norway [240149/F20]. Dr. Klarin is supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute of the National Institutes of Health under award number T32 HL007734.

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at doi:10.1038/s41598-017-09396-7

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Christiansen, C. B. et al. Atrial fibrillation and risk of stroke: a nationwide cohort study. Europace: European pacing, arrhythmias, and cardiac electrophysiology: journal of the working groups on cardiac pacing, arrhythmias, and cardiac cellular electrophysiology of the European Society of Cardiology, euv401 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Vermond RA, et al. Incidence of atrial fibrillation and relationship with cardiovascular events, heart failure, and mortality: a community-based study from the Netherlands. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2015;66:1000–1007. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2015.06.1314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aronow WS, Banach M. Atrial Fibrillation: The New Epidemic of the Ageing World. Journal of atrial fibrillation. 2009;1:154. doi: 10.4022/jafib.v1i6.530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shariff N, et al. Rate-control versus rhythm-control strategies and outcomes in septuagenarians with atrial fibrillation. The American journal of medicine. 2013;126:887–893. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2013.04.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Benjamin EJ, et al. Independent risk factors for atrial fibrillation in a population-based cohort: the Framingham Heart Study. Jama. 1994;271:840–844. doi: 10.1001/jama.1994.03510350050036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Iguchi Y, et al. Prevalence of Atrial Fibrillation in Community-Dwelling Japanese Aged 40 Years or Older in Japan Analysis of 41,436 Non-Employee Residents in Kurashiki-City. Circulation Journal. 2008;72:909–913. doi: 10.1253/circj.72.909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kannel WB, Benjamin EJ. Status of the epidemiology of atrial fibrillation. Medical Clinics of North America. 2008;92:17–40. doi: 10.1016/j.mcna.2007.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kannel WB, Wolf PA, Benjamin EJ, Levy D. Prevalence, incidence, prognosis, and predisposing conditions for atrial fibrillation: population-based estimates. The American journal of cardiology. 1998;82:2N–9N. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9149(98)00583-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Krahn AD, Manfreda J, Tate RB, Mathewson FAL, Cuddy TE. The natural history of atrial fibrillation: incidence, risk factors, and prognosis in the Manitoba Follow-Up Study. The American journal of medicine. 1995;98:476–484. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9343(99)80348-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Smith JG, Platonov PG, Hedblad B, Engstrom G, Melander O. Atrial fibrillation in the Malmo Diet and Cancer study: a study of occurrence, risk factors and diagnostic validity. European journal of epidemiology. 2010;25:95–102. doi: 10.1007/s10654-009-9404-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wanahita N, et al. Atrial fibrillation and obesity—results of a meta-analysis. American heart journal. 2008;155:310–315. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2007.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Arnar DO, et al. Familial aggregation of atrial fibrillation in Iceland. European heart journal. 2006;27:708–712. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehi727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Christophersen IE, et al. Familial aggregation of atrial fibrillation a study in Danish twins. Circulation: Arrhythmia and Electrophysiology. 2009;2:378–383. doi: 10.1161/CIRCEP.108.786665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ellinor PT, Yoerger DM, Ruskin JN, MacRae CA. Familial aggregation in lone atrial fibrillation. Human genetics. 2005;118:179–184. doi: 10.1007/s00439-005-0034-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fox CS, et al. Parental atrial fibrillation as a risk factor for atrial fibrillation in offspring. Jama. 2004;291:2851–2855. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.23.2851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lubitz SA, et al. Association between familial atrial fibrillation and risk of new-onset atrial fibrillation. Jama. 2010;304:2263–2269. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.1690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Marcus GM, et al. A first-degree family history in lone atrial fibrillation patients. Heart rhythm: the official journal of the Heart Rhythm Society. 2008;5:826–830. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2008.02.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Benjamin EJ, et al. Variants in ZFHX3 are associated with atrial fibrillation in individuals of European ancestry. Nature genetics. 2009;41:879–881. doi: 10.1038/ng.416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ellinor PT, et al. Common variants in KCNN3 are associated with lone atrial fibrillation. Nature genetics. 2010;42:240–244. doi: 10.1038/ng.537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gudbjartsson DF, et al. Variants conferring risk of atrial fibrillation on chromosome 4q25. Nature. 2007;448:353–357. doi: 10.1038/nature06007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gudbjartsson DF, et al. A sequence variant in ZFHX3 on 16q22 associates with atrial fibrillation and ischemic stroke. Nature genetics. 2009;41:876–878. doi: 10.1038/ng.417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sinner, M. F. et al. Integrating genetic, transcriptional, and functional analyses to identify five novel genes for atrial fibrillation. Circulation, CIRCULATIONAHA-114 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 23.Gong J, et al. Genome-Wide Interaction Analyses between Genetic Variants and Alcohol Consumption and Smoking for Risk of Colorectal Cancer. PLoS genetics. 2016;12:e1006296. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1006296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gauderman WJ. Sample size requirements for matched case‐control studies of gene–environment interaction. Statistics in medicine. 2002;21:35–50. doi: 10.1002/sim.973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kääb S, et al. Large scale replication and meta-analysis of variants on chromosome 4q25 associated with atrial fibrillation. European heart journal. 2009;30:813–819. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehn578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mommersteeg MTM, et al. Pitx2c and Nkx2-5 are required for the formation and identity of the pulmonary myocardium. Circulation research. 2007;101:902–909. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.107.161182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tessari A, et al. Myocardial Pitx2 differentially regulates the left atrial identity and ventricular asymmetric remodeling programs. Circulation research. 2008;102:813–822. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.107.163188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang J, et al. Pitx2 prevents susceptibility to atrial arrhythmias by inhibiting left-sided pacemaker specification. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2010;107:9753–9758. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0912585107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kirchhof P, et al. PITX2c is expressed in the adult left atrium, and reducing Pitx2c expression promotes atrial fibrillation inducibility and complex changes in gene expression. Circulation: Cardiovascular Genetics. 2011;4:123–133. doi: 10.1161/CIRCGENETICS.110.958058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Heo M, Faith MS, Pietrobelli A. Resistance to change of adulthood body mass index. International journal of obesity and related metabolic disorders: journal of the International Association for the Study of Obesity. 2002;26:1404–1405. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0802076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Manning AK, et al. Meta-analysis of gene-environment interaction: joint estimation of SNP and SNP x environment regression coefficients. Genetic epidemiology. 2011;35:11–18. doi: 10.1002/gepi.20546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Alonso A, et al. Incidence of atrial fibrillation in whites and African-Americans: the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) study. American heart journal. 2009;158:111–117. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2009.05.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ambale-Venkatesh B, et al. Diastolic function assessed from tagged MRI predicts heart failure and atrial fibrillation over an 8-year follow-up period: the multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis. European Heart Journal-Cardiovascular Imaging. 2014;15:442–449. doi: 10.1093/ehjci/jet189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bild DE, et al. Multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis: objectives and design. American journal of epidemiology. 2002;156:871–881. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwf113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Conen D, et al. Alcohol consumption and risk of incident atrial fibrillation in women. Jama. 2008;300:2489–2496. doi: 10.1001/jama.2008.755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dawber TR, Meadors GF, Moore FE., Jr Epidemiological Approaches to Heart Disease: The Framingham Study*. American Journal of Public Health and the Nations Health. 1951;41:279–286. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.41.3.279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fried LP, et al. The cardiovascular health study: design and rationale. Annals of epidemiology. 1991;1:263–276. doi: 10.1016/1047-2797(91)90005-W. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Harris TB, et al. Age, Gene/Environment Susceptibility–Reykjavik Study: multidisciplinary applied phenomics. American journal of epidemiology. 2007;165:1076–1087. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwk115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Heeringa J, et al. Prevalence, incidence and lifetime risk of atrial fibrillation: the Rotterdam study. European heart journal. 2006;27:949–953. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehi825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hofman A, et al. The Rotterdam Study: objectives and design update. European journal of epidemiology. 2007;22:819–829. doi: 10.1007/s10654-007-9199-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.John U, et al. Study of Health In Pomerania (SHIP): a health examination survey in an east German region: objectives and design. Sozial-und Präventivmedizin. 2001;46:186–194. doi: 10.1007/BF01324255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kannel WB, Feinleib M, McNamara PM, Garrison RJ, Castelli WP. An investigation of coronary heart disease in families The Framingham offspring study. American journal of epidemiology. 1979;110:281–290. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a112813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kathiresan S, et al. Genome-wide association of early-onset myocardial infarction with single nucleotide polymorphisms and copy number variants. Nature genetics. 2009;41:334–341. doi: 10.1038/ng.327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nabauer M, et al. The Registry of the German Competence NETwork on Atrial Fibrillation: patient characteristics and initial management. Europace : European pacing, arrhythmias, and cardiac electrophysiology : journal of the working groups on cardiac pacing, arrhythmias, and cardiac cellular electrophysiology of the European Society of Cardiology. 2009;11:423–434. doi: 10.1093/europace/eun369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nieminen T, et al. The Finnish Cardiovascular Study (FINCAVAS): characterising patients with high risk of cardiovascular morbidity and mortality. BMC cardiovascular disorders. 2006;6:9. doi: 10.1186/1471-2261-6-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rexrode KM, Lee IM, Cook NR, Hennekens CH, Buring JE. Baseline characteristics of participants in the Women's Health Study. Journal of women's health & gender-based medicine. 2000;9:19–27. doi: 10.1089/152460900318911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ridker PM, et al. Rationale, design, and methodology of the Women’s Genome Health Study: a genome-wide association study of more than 25 000 initially healthy American women. Clinical chemistry. 2008;54:249–255. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2007.099366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Roden DM, et al. Development of a large‐scale de‐identified DNA biobank to enable personalized medicine. Clinical Pharmacology & Therapeutics. 2008;84:362–369. doi: 10.1038/clpt.2008.89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Shepherd J, et al. The design of a prospective study of pravastatin in the elderly at risk (PROSPER) The American journal of cardiology. 1999;84:1192–1197. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9149(99)00533-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Teixeira, P. L. et al. Evaluating electronic health record data sources and algorithmic approaches to identify hypertensive individuals. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association, ocw071 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 51.Weeke P, et al. Examining Rare and Low-Frequency Genetic Variants Previously Associated With Lone or Familial Forms of Atrial Fibrillation in an Electronic Medical Record System A Cautionary Note. Circulation: Cardiovascular Genetics. 2015;8:58–63. doi: 10.1161/CIRCGENETICS.114.000718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Winkelmann BR, et al. Rationale and design of the LURIC study-a resource for functional genomics, pharmacogenomics and long-term prognosis of cardiovascular disease. Pharmacogenomics. 2001;2:S1–S73. doi: 10.1517/14622416.2.1.S1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Aric I. The atherosclerosis risk in communit (aric) stui) y: Design and objectwes. American journal of epidemiology. 1989;129:687–702. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a115184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wichmann HE, Gieger C, Illig T, group, M. K. s KORA-gen-resource for population genetics, controls and a broad spectrum of disease phenotypes. Das Gesundheitswesen. 2005;67:26–30. doi: 10.1055/s-2005-858226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Willer CJ, Li Y, Abecasis GR. METAL: fast and efficient meta-analysis of genomewide association scans. Bioinformatics. 2010;26:2190–2191. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ellinor PT, et al. Meta-analysis identifies six new susceptibility loci for atrial fibrillation. Nature genetics. 2012;44:670–675. doi: 10.1038/ng.2261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lubitz SA, et al. Novel genetic markers associate with atrial fibrillation risk in Europeans and Japanese. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2014;63:1200–1210. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.12.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.