Abstract

Background

There have not been any population-based surveys in Germany to date on the frequency of various types of sexual behavior. The topic is of interdisciplinary interest, particularly with respect to the prevention and treatment of sexually transmitted infections.

Methods

Within the context of a survey that dealt with multiple topics, information was obtained from 2524 persons about their sexual orientation, sexual practices, sexual contacts outside relationships, and contraception.

Results

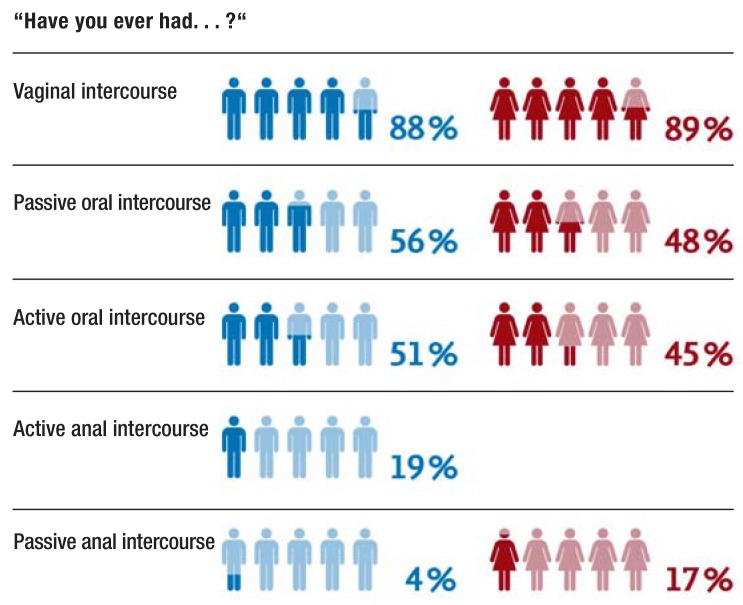

Most of the participating women (82%) and men (86%) described themselves as heterosexual. Most respondents (88%) said they had engaged in vaginal intercourse at least once, and approximately half said they had engaged in oral intercourse at least once (either actively or passively). 4% of the men and 17% of the women said they had been the receptive partner in anal intercourse at least once. 5% of the respondents said they had had unprotected sexual intercourse outside their primary partnership on a single occasion, and 8% said they had done so more than once; only 2% of these persons said they always used a condom during sexual intercourse with their primary partner. Among persons reporting unprotected intercourse outside their primary partnership, 25% said they had undergone a medical examination afterward because of concern about a possible sexually transmitted infection.

Conclusion

Among some groups of persons, routine sexual-medicine examinations may help contain the spread of sexually transmitted infections. One component of such examinations should be sensitive questioning about the types of sexual behavior that are associated with a high risk of infection. Information should be provided about the potential modes of transmission, including unprotected vaginal, oral, and anal intercourse outside the primary partnership.

Sexual health is “a state of physical, emotional, mental and social wellbeing in relation to sexuality, and not merely the absence of disease, dysfunction or infirmity“ (1). According to the World Health Organization (2), sexual health is closely linked to wellbeing and quality of life. To consider sexual health in the setting of health policy and identify risks in the healthcare system, representative data on the sexual behavior over the lifespan are crucial. With regard to German people’s sexual lives, only very few scientific studies are available, and these focus mostly on specific subgroups—among others, homosexual men (e1), adolescents (e2), and students (e3). For the general German population, data on sexual behavior based on a representative sample have thus far not been collected. Such studies have, however, been conducted in other countries (for example, the US, the UK, Australia, Sweden) (3– 5, e4, e5). In the age group 25–44 years, vaginal intercourse was reported to be the most common practice (98% of women, 97% of men (3). Rates of oral intercourse were 89% in women versus 90%) in men (3), and rates of anal intercourse 36% in women and 44% in men (3). Reported rates of same-sex contacts were 12% in women and 6% in men (3). According to German-language cohort studies, 15–26% of women and 17–32% of men reported sexual contacts outside their current steady relationship (see [6] for an overview). An online survey found rates of 4% for homosexual women and 34% for homosexual men, 29% for heterosexual women and 49% for heterosexual men (7). Such studies, however, are subject to several biases (for example, as a result of the sampling and self-selection).

Sexually transmitted infections (STIs) present an interdisciplinary challenge. Incidence rates of the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV: 3200 incident infections in 2015, 95% confidence interval [3000; 3400]) and non-notifiable STIs (Chlamydia trachomatis, gonorrhea) have remained constant in Germany in recent years (8, 9), whereas the incidence of syphilis has steadily risen since 2010 (8.5 cases per 100 000 population in 2015) (10). The rise in new cases of infection is based primarily on increased numbers of reports of men who have sex with men (MSM) (10). Since no current epidemiological data are available, it is not possible to estimate the incidence rates of genital herpes (Herpes simplex viruses, HSV-1, HSV-2) and HPV infections (human papillomaviruses). Due to the increasing uptake of the HPV vaccine, it may be assumed that the prevalence rates of these STIs have fallen in recent years (e6– e8). STIs can cause neonatal harms (for example, owing to genital herpes), lead to genital and extragenital neoplasms (for example, as a result of HPV infection), or cause infertility (as a result of infection with Chlamydia trachomatis) (11, 12).

Transmission routes of STIs include unprotected vaginal, anal, and oral intercourse (13). Because of inconsistent use of condoms during sexual contacts outside the main relationship while simultaneously dispensing with condoms within the relationship, clandestine sexual contacts outside the relationship are seen as a transmission route for STIs to spread (14, 15). Similarly, unwanted pregnancies in the context of unprotected sexual intercourse are of relevance: in addition to contraceptive failure and non-compliance, unprotected sexual intercourse is the reason why interceptive drugs are prescribed. About 13% of women have used an interceptive at least once (16).

The aim of this study is to provide an overview of different sexual behaviors on the basis of a sample that is representative for age and sex. This furnishes persons working in the healthcare system with an information base that may be useful when taking a sexual history, preventing and treating STIs, treating sexual dysfunctions, or delivering sex education.

Methods

Sociodemographic data were collected nationwide by means of face to face interviews on site. Subsequently, study subjects were given a questionnaire to complete independently, which asked questions on sexual orientation, relationships, contraception, sexual behavior, and sexual contacts outside existing relationships. A total of 2524 persons were interviewed, 45% of these were men and 55% women (table 1). Before the data evaluation, the researchers conducted plausibility tests on the basis of the complete data sets. By using weighted adjustments, each case was weighted; consequently the sample matched the German population for the combination of characteristics “age and sex“ and “place of residence by federal state.” A detailed description of the data collection, measuring instruments, and evaluation can be found in the Supplementary material.

Table 1. Sociodemographic data.

| Total (N = 2524) | Men (n = 1145) | Women (n = 1379) | ||||

| Age | ||||||

| Mean [95% CI] | 48.48 [48.13; 49.55] | 48.44 [47.38; 49.50] | 49.17 [48.21; 50.12] | |||

| Range | 14–99 | 14–93 | 14–99 | |||

| Sexual orientation | N | % | n | % | n | % |

| Heterosexual | 2118 | 84 | 986 | 86 | 1132 | 82 |

| Mostly heterosexual | 86 | 3 | 32 | 3 | 54 | 4 |

| Bisexual | 21 | 1 | 10 | 1 | 11 | 1 |

| Mostly homosexual | 11 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 7 | 1 |

| Homosexual | 22 | 1 | 11 | 1 | 11 | 1 |

| Not clear/uncertain | 19 | 1 | 11 | 1 | 8 | 1 |

| Other | 100 | 4 | 40 | 3 | 60 | 4 |

| N/A | 147 | 6 | 51 | 4 | 96 | 7 |

| Family status | ||||||

| Married/cohabiting | 1040 | 41 | 501 | 44 | 539 | 39 |

| Married/living in separation | 54 | 2 | 23 | 2 | 31 | 2 |

| Unmarried | 776 | 31 | 407 | 36 | 369 | 27 |

| Divorced | 391 | 15 | 140 | 12 | 251 | 18 |

| Widowed | 256 | 10 | 71 | 6 | 185 | 13 |

| N/A | 7 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 4 | 0 |

95% CI, 95% confidence interval.

Results

Sexual orientation

Most women (82%) and men (86%) described themselves as exclusively heterosexual (table 1). Heterosexual attraction (men: mean = 3.78; 95% confidence interval [3.71; 3.86]; women: mean = 3.25 [3.17; 3.33]) was much more common than attraction to a person of the same sex (men: mean = 1.16 [1.11; 1.20]; women: mean = 1.25 [1.20; 1.29]; as measured on a 5-point Likert scale: 1 = never/not at all, 5 = very strongly). Most men (83%) and women (78%) when asked for the number of sexual partners during their lives to date (lifetime sexual partners) reported heterosexual sexual contacts. Only 5% of men and 8% of women reported having had sexual contacts with the same sex.

Relationships

57% of those interviewed reported being in a stable relationship at the time of the survey. Altogether, subjects tended to be satisfied with their relationships. Of the 57% of subjects in stable relationships, 40% had a monogamous relationship, 2% an open relationship, and 1% had agreed to have relationships including a third partner. 56% had not negotiated any agreement regarding contacts with third partners.

Contraception

Of the 57% of subjects in stable relationships, 76% reported that they never used condoms within their relationship, 12% reported occasional condom use, 3% frequent condom use, and 6% reported that they always used a condom. 4% did not answer the question. Of the women of childbearing age (= 50 years), 51% reported that they were taking oral contraceptives, 17% used other kinds of contraception. 5% did not use any contraception as they wanted to have children; 27% reported that they did not think about using contraception. 7% had taken interceptives for the purpose of postcoital contraception; 3% had taken an interceptive more than once. 8% did not answer the question.

Sexual behaviors

Table 2, Figure 1, and eTable 1 provide an overview of reported sexual behaviors in men and women. Detailed reported rates of sexual practices by sex and age are shown in eTables 1– 5.

Table 2. Frequency of sexual practices in the past year.

| Men | Women | |

| Mean [95% CI] | Mean [95% CI] | |

| Vaginal intercourse | ||

| 32.71 [29.41; 36.01] (n = 745) |

25.16 [21.62; 28.70] (n = 836) |

|

| Performed oral sex | ||

| On women | 12.87 [10.33; 15.40] (n = 474) |

1.36 [0.55; 2.17] (n = 385) |

| On men | 0.79 [0.18; 1.40] (n = 390) |

7.29 [5.68; 8.90] (n = 448) |

| Received oral sex | ||

| Given by women | 11.01 [8.91; 13.11] (n = 372) |

0.96 [0.28; 1.64] (n = 324) |

| Given by men | 0.76 [0.18; 1.35] (n = 372) |

8.23 [6.22; 10.24] (n = 324) |

| Anal intercourse, passive | ||

| Given by men | 9.97 [2.86; 17.09] (n = 35) |

4.47 [3.18; 5.75] (n = 189) |

| Anal intercourse, active | ||

| In men | 2.23 [0.48; 3.98] (n = 151) |

– |

| In women | 4.01 [2.58; 5.43] (n = 151) |

– |

95% CI, 95% confidence interval.

The reported means were calculated on the basis of the respective sample sizes

Figure 1.

Frequency of sexual practices

eTable 1. Frequency of sexual practices.

| Men (n = 1145) | Women (n = 1379) | |

| n (%) | n (%) | |

| Vaginal intercourse | ||

| Yes | 1008 (88) | 1226 (89) |

| No | 66 (6) | 86 (6) |

| N/A | 71 (6) | 67 (5) |

| Performed oral sex | ||

| Yes | 588 (51) | 624 (45) |

| No | 473 (41) | 641 (47) |

| N/A | 84 (7) | 114 (8) |

| Received oral sex | ||

| Yes | 641 (56) | 665 (48) |

| No | 419 (37) | 594 (43) |

| N/A | 85 (7) | 120 (9) |

| Anal intercourse, passive | ||

| Yes | 47 (4) | 238 (17) |

| No | 994 (87) | 1034 (75) |

| N/A | 104 (9) | 107 (8) |

| Anal intercourse, active | ||

| Yes | 222 (19) | – |

| No | 847 (74) | – |

| N/A | 76 (7) | – |

N/A, no answer

Sexual contacts outside relationships

17% of those interviewed reported ever having had sexual intercourse with someone other than their partner while being in a steady relationship. 5% did not did not answer the question. More men (21%) than women (15%) answered in the affirmative when asked if they had had sexual contacts outside their relationships (?2 [2] = 17 972, p = 0.001). Persons who had had sexual contacts outside their relationships reported a mean of 3.65 other sexual partners (range = 1–199; 95% confidence interval [2.51; 4.79]) in addition to their primary partners; 40 persons did not answer the question. 7% reported having had sex outside their current relationship; 4% did not answer the question. Differences between the sexes reached significance (?2 [2] = 4724, p = 0.030): more men (8%) than women (6%) reported having sexual contacts outside their current primary relationships. Persons who had had sexual contacts outside their current relationships reported a mean of 2.71 other sexual partners (range = 1–20 [2.06; 3.36]) during that relationship; 10 persons did not give an answer regarding the number. 8% of men (n = 89) reported contacts with a mean of 4.06 [2.15; 5.97] female prostitutes. Very few men (0.01%; n = 8) reported sexual contacts outside their relationships with a mean of 2.38 [0.72; 4.04] male prostitutes. Women were not asked for sexual contacts with prostitutes as the researchers were wary of the risk of dropouts from the study as a result of such questions.

Unprotected sexual intercourse

82% of study participants reported never having had unprotected sex outside their primary relationship, 5% reported having had unprotected sex once, and 8% reported more than one occurrence. Of those who had had unprotected sex outside their relationship, 16% had sought out a subsequent medical examination for fear of having contracted an STI once and 9% more than once; 74% reported that they had not had any examination; 1% did not answer the question. Only 2% of those who had had unprotected sex outside their relationships always used condoms during sex with their steady partner. 38% reported never using condoms in their primary relationship, and 7% reported using condoms occasionally; 3% reported using condoms often.

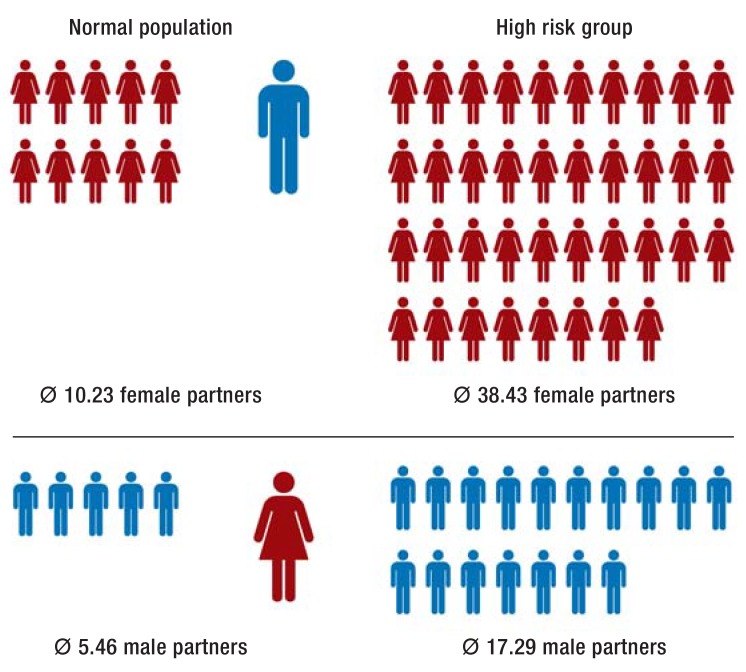

On the basis of the assumption that STIs may be associated with the number of lifetime sexual partners, we determined a subgroup with an increased risk for STIs (n = 35 men, n = 27 women), who had reported sexual contacts outside their current relationship, unprotected sexual intercourse outside, and inconsistent condom use within, their relationship. Men from this high-risk group reported a mean of 38 female sexual partners, women reported a mean of 17 male sexual partners (figure 2). The number of sexual partners in the high-risk group was three times as high as in persons who did not meet all the listed criteria (normal population). Of those persons who had reported sexual contacts with prostitutes (n = 93), 36% reported never using condoms with their primary partners. Only 4% each reported using condoms occasionally, often, or always. Half of those who reported sexual contact with prostitutes reported having had unprotected sex outside their relationship (once: 18%; more than once: 33%). The data do not convey any information on the occurrence or frequency of unprotected sex with prostitutes.

Figure 2.

Mean lifetime number of sexual partners

Discussion

Subjects aged 25–29 were the most sexually active age group, as was also shown by a previous study (4). Increasing age was observed to be accompanied by a decreased frequency in sexual activity; the causes may be the length of the relationship (17) as well as aging (for example, as a result of falling testosterone concentrations) (e9). Similar to the results from research from the US and the UK to date (3, 5), the responses from men and women differed regarding the numbers of their sexual partners. Self-serving biases and gender-specific responding behavior may have contributed to the differing responses. As far as we know the reasons for these differing responses have not been investigated to date. Data from questionnaire surveys have also not been validated on the basis of behavioral data. Compared with earlier, non-representative studies, fewer subjects reported active or passive oral intercourse, and the same was true for insertive and receptive anal intercourse. This may be because of cultural differences (3, 4) or online based data collections (18).

The proportion of persons who reported having sexual contacts outside their relationship was low compared with earlier studies (6, 7). Many partners therefore seemed to be true to the widespread desire for faithful relationships (e10). Because of the random selection of the sample and the independent completion of the questionnaires it can be assumed that the data are less prone to biases and the rates shown are more reliable than in other studies.

It is of particular relevance that participants reported having had unprotected sex outside their primary relationships, and of these, only 2% reported using condoms at all times within their relationship. In a scenario of changing sexual partners and inconsistent condom use, regular sexual medical examinations are recommended, because STIs will otherwise remain undetected at first (19). Only one in four of those who answered in the affirmative about having unprotected sexual intercourse outside their steady relationship had undergone a relevant medical examination. Simultaneously, some persons displayed behaviors (external contacts, unprotected sexual intercourse outside their relationships, inconsistent condom use, a higher lifetime number of sexual partners) that are to be considered as at risk with regard to STIs. If one considers that more than 80% of 18- to 40-year-olds reported in another survey that they had never been comprehensively asked about their sexuality when they had contact with physicians (Brenk-Franz K, Strauß B [in preparation]: The medical care of persons with sexual dysfunction), our results underline the necessity of exploring in detail high-risk behaviors and of providing factual and structured education for the prevention of STIs. In addition, the guideline (20) recommends that the HPV (types 16 and 18) vaccine be given to girls for cancer prevention as early as possible.

Whether vaccination at a later date—especially after the start of sexual activity—is indicated should be decided on an individual basis (20). A detailed sexual history is helpful and required in this setting.

The results should be viewed while considering the composition of the sample. Participants mainly reported being heterosexual. The proportion of homosexual subjects was consistent with the proportions reported in other German-language publications (21). The proportion of those who reported same-sex sexual partners (5–8%) was lower than in studies from the US (10%; [e11]) and UK (7–16%; [5]). Because of the small subsample sizes, no conclusions were possible with regard to specific subgroups (for example, those with a homosexual identity). To this end, a disproportional number of such subgroups compared with the total population would have been required in the sample (oversampling). For reasons of economy we also dispensed with capturing data on body image and satisfaction with the reported sexual behaviors. Similarly we were not able to find out which factors (for example, consumption of pornography) affect the sexual practices undertaken. And neither did we focus on contraceptive use in specific sexual behaviors. For example, in orogenital sexual encounters, protective measures were used notably less often, even in case of multiple partners, because of ignorance vis-à-vis the risk of infection (22). Certain criteria (age, sex, place of residence) were weighted during recruitment, so that the sample largely matched the total population of Germany. However, individual reports of frequencies may be subject to bias because the willingness to answer a question varied by the subject of the question. Although a recommended computer aided self interview was used to capture sensitive data, we found many missing values (17–43%). We decided against estimating the missing data and reported confidence intervals. Self-serving memory biases and self-portrayals have to be assumed as a matter of principle in the setting of reporting sexual behaviors. As self-reported sexual behaviors are also subject to biases when using other data collection methods (e12), in future, partners should be interviewed about the behaviors and experiences of their significant other, in order to validate their responses. A longitudinal study design would help identify predictors for high-risk sexual behaviors.

Clinical Implications.

Persons with changing sexual partners should be explicitly educated about the transmission pathways of sexually transmitted infections (STIs) (for example, the less well known orogenital transmission pathway) and condom/femidom use.

As is recommended in the S1 guideline on STIs (19), persons with changing sexual partners should regularly be examined in exploratory and advisory consultations and should have sexual medical exams (clinical examination and laboratory tests).

The sexual partners of persons with diagnosed STIs should also be examined, as long as the infected partner releases the doctor from adhering to strict patient confidentiality.

In addition to the more detailed explanation of transmission pathways and protective measures for STIs in screening examinations for adolescents, all girls should be vaccinated against HPV, depending on the vaccine at age 9–13 or 9–14, following the recommendations of the Standing Vaccination Committee (STIKO) (23). As indications are that women may benefit from the vaccine even at a later stage, information should be provided and a decision about this should be reached jointly with the patient (20).

Key Messages.

Representative studies of specific aspects of sexual behavior provide an important basis for gauging a sexual history for educating/informing patients.

Sexually transmitted infections may spread further because of inconsistent condom use in a scenario of changing sexual partners. 13% of study participants reported having had unprotected sexual intercourse outside their primary relationship; of these, only 2% always used condoms during sex with their primary partner.

7% of women had taken an interceptive for the purpose of postcoital contraception; 3% had taken one more than once.

8% of men reported having had sex with prostitutes at least once.

Methods.

The data were collected in the context of a survey including several subjects, which was coordinated by personnel at Leipzig University’s Department of Medicine. After approval by the ethics committee at Leipzig University’s Department of Medicine (Ref: 452–15–21122015), the survey was conducted by the USUMA (Unabhängiger Service für Umfragen, Methoden und Analysen [independent service for surveys, methods, and analyses]) market and social research institute. The data collection took 8 weeks (20 January to 16 March 2016). The study collected data on unemployment, migration background, different attitudes (among others, on religiousness, right-extremist attitudes, democracy), and mental wellbeing.

The target households were identified after the regional areas were subdivided by using the random route method. The random selection of target _persons was done by using the Kish selection grid (e13). All persons in a household were allocated a number by entering them into a schema by sex and age (descending). The person whose number appeared first in a series of random numbers was included in the survey; the order of random numbers in the data collection protocols varied. Together with the interviewer, sociodemographic data relating to the target person and household were identified in a face-to-face survey/interview on site by using the demographic standard of the Federal Statistical Office (age, nationality, living in West/East Germany, family status, cohabitation with partner, school leaving certificate, gainful employment, net household income, religious affiliation). Subsequently the questionnaire was handed to those surveyed. Because of the in some cases very personal data, the idea was for participants to complete this independently. Finally the subject handed the completed questionnaire to the interviewer.

• Description of the sample

Altogether 2524 persons were included in the survey (German-speaking residential population; minimum age 14 years; response rate 52.3% (etable 1); 45% of responders were male and 55% female. By applying adjustment weighting for the combination of the characteristics “age and sex“ and “place of residence by federal state,“ any non-response bias was reduced, so that the sample matched the characteristics of the German

population. The average age was 48.48 years (95% CI [48.13; 49.55]). eTable 2 shows sociodemographic data.

• Measuring instruments

In compiling the questionnaire, existing German and international measuring instruments were used. English-language items were translated and used after detailed checking by different psychologists. The items were not validated separately.

-

Sexual orientation

This was elicited by using the data on sexual identity (heterosexual, mostly heterosexual, bisexual, mostly homosexual, homosexual, unclear/uncertain, other), on the sexual attraction of men and women (1 = never/not at all, 5 = very strongly), and the number of same-sex and opposite-sex sexual partners (e11).

-

Relationship and contraception

Where a steady relationship was reported, the duration of this relationship, global satisfaction with the partner (1 = very unhappy, 6 = very happy) (e14) and agreements on sexual faithfulness (open relationship, monogamous relationship, third parties permitted, no agreement) (7). Additionally, questions were asked about condom use in the primary relationship (1 = never, 4 = always) (16) and in women their use of oral contraceptives and interceptives (16).

-

Sexual behavior

Initially we collected data on whether the subjects had ever practiced certain sexual practices. Questions of frequency were asked of only those subjects who had reported to, for example, have ever had vaginal intercourse. If vaginal intercourse was reported, subjects were asked for the frequency of vaginal intercourse in the past year and the preceding month. For oral and anal intercourse, frequencies for the past year were asked separately for the sex of the sexual partners as well as for active/insertive and passive/receptive (3).

-

Sexual contacts outside the main relationship

We collected data on the occurrence and frequency of extra-relationship sexual contacts. We differentiated between such contacts while in the current relationship as well as ever. Furthermore, we asked about outside-relationship contact with prostitutes. Unprotected sexual intercourse outside the relationship as well as medical examinations out of worry about sexually transmitted infections (STIs) were also documented.

• Evaluation

Before the evaluation, plausibility checks were undertaken on the basis of the full data sets (for all sections of the multiple-subject survey). Descriptive statistics were reported in absolute and relative rates. The respective sample size that the data referred to was given. This can vary because certain questions were asked only when certain conditions applied (for example, duration of the relationship only when a relationship actually existed) or if subjects did not answer the question. Furthermore, we calculated frequencies in means with corresponding 95% confidence intervals. Chi square tests were used to compare results between the sexes.

eTable 2. Response rates.

| n | % | |

| Gross approach | 4902 | 100 |

| Quality neutral failures | 72 | 1.5 |

| Residence not inhabited | 54 | 1.1 |

| No person of the basic population in household | 18 | 0.4 |

| Address not used | 0 | 0 |

| Net sample (address used) | 4830 | 100 |

| Systematic failures | 2286 | 47.3 |

| Of which: | ||

| Household not encountered in four visits | 693 | 14.3 |

| Household refuses to give information | 721 | 14.9 |

| Target person not encountered in four visits | 104 | 2.2 |

| Target person away, holidays | 23 | 0.5 |

| Target person ill, not able to follow the interview | 14 | 0.3 |

| Target person refuses interview | 731 | 15.1 |

| Interviews conducted | 2544 | 52.7 |

| Non-evaluable interviews | 20 | 0.4 |

| Evaluated interviews/response rate | 2524 | 52.3 |

eTable 3. Sociodemographic data.

| Total (N = 2524) | Men (n = 1145) | Women (n = 1379) | ||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| Highest school leaving certificate | ||||||

| General secondary school (year 9 ‧lower secondary school certificate) not completed | 59 | 2 | 26 | 2 | 33 | 2 |

| Year 9 lower secondary school certificate | 763 | 30 | 351 | 31 | 412 | 30 |

| Intermediate secondary school completed | 815 | 32 | 340 | 30 | 475 | 34 |

| Polytechnic secondary school completed (10th year) | 189 | 7 | 87 | 8 | 102 | 7 |

| Technical school “Abitur“ (A level equivalent) (not acknowledged) |

83 | 3 | 40 | 3 | 43 | 3 |

| University entrance certification (“Abitur”), but university degree not completed | 285 | 11 | 127 | 11 | 158 | 11 |

| Degree from university or technical university | 253 | 10 | 130 | 11 | 123 | 9 |

| Students at a general school | 75 | 3 | 43 | 4 | 32 | 2 |

| Special needs school | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Nationality | ||||||

| German | 2420 | 96 | 1082 | 94 | 1338 | 97 |

| Non-German | 104 | 4 | 63 | 6 | 41 | 3 |

| Housing/domestic set-up | ||||||

| Cohabiting | 1317 | 52 | 635 | 56 | 682 | 50 |

| Not cohabiting | 1171 | 47 | 493 | 43 | 678 | 49 |

| N/A | 36 | 1 | 17 | 1 | 19 | 1 |

| Net household income | ||||||

| < €1250/month | 456 | 18 | 171 | 15 | 285 | 21 |

| €1250–2500/month | 1068 | 42 | 483 | 42 | 585 | 42 |

| > €2500/month | 913 | 36 | 462 | 40 | 451 | 33 |

| N/A | 87 | 3 | 29 | 3 | 58 | 4 |

N/A, no answer

eTable 4a. Age specific data on the sexual practices of men (n = 1145).

|

Sexual practice ever undertaken % [95% CI] |

Vaginal intercourse (n = 1074) |

Performed oral sex (n = 1061) |

Received oral sex (n = 1060) |

Anal intercourse, receptive (n = 1041) |

Anal intercourse, insertive (n = 1069) |

| Age | |||||

| 14–18 years (n = 60) |

42.1 [30.1; 55.1] |

25.5 [15.8; 38.4] |

25.9 [16.1; 39.0] |

1.8 [0.4; 9.6] |

5.6 [2.0; 15.1] |

| 19–24 years (n = 78) |

94.5 [86.7; 97.8] |

56.1 [44.7; 67.0] |

63.5 [52.1; 73.6] |

8.1 [3.8; 16.6] |

19.4 [12.1; 29.7] |

| 25–29 years (n = 77) |

94.4 [86.6; 97.7] |

75.3 [64.3; 83.7] |

73.6 [62.4; 82.4] |

11.3 [5.9; 20.7] |

35.6 [25.6; 47.1] |

| 30–39 years (n = 160) |

97.3 [93.3; 98.9] |

71.3 [63.6; 78.0] |

80.8 [73.8; 86.3] |

6.7 [3.7; 12.0] |

28.4 [21.7; 36.1] |

| 40–49 years (n = 202) |

98.4 [95.6; 99.4] |

69.8 [62.9; 76.0] |

71.1 [64.2; 77.0] |

3.2 [1.5; 6.8] |

27.4 [21.5; 34.3] |

| 50–59 years (n = 226) |

97.1 [94; 98.7] |

62.0 [55.3; 68.2] |

68.3 [61.7; 74.2] |

3.8 [2.0; 7.3] |

24.8 [19.5; 30.1] |

| 60–69 years (n = 184) |

96.5 [92.6; 98.4] |

42.9 [35.0; 50.4] |

51.5 [44.0; 59.0] |

4.4 [2.2; 8.7] |

12.1 [8.0; 17.8] |

| 70–79 years (n = 114) |

97.1 [91.8; 99.0] |

25.5 [18.4; 34.8] |

32.0 [23.8; 41.6] |

1.0 [0.2; 5.5] |

7.8 [4.1; 14.7] |

| 80–100 years (n = 44) |

92.3 [79.6; 97.2] |

23.7 [13.0; 39.3] |

18.4 [9.3; 33.5] |

0.0 [0; 9.5] |

5.4 [1.7; 17.8] |

95% CI, 95% confidence interval of the mean

eTable 4b. Age specific data on the sexual practices of men (n = 1145).

|

Frequency Mean [95% CI] |

Vaginal intercourse | Performed oral sex | Received oral sex |

Anal intercourse, receptive |

Anal intercourse, insertive | ||||

|

Vaginal intercourse *1 |

Vaginal intercourse *2 |

On men*2 | On women*2 | Given by men*2 | Given by women*2 | Given by men*2 | In men*2 | In women*2 | |

| Age | |||||||||

| 14–18 years | 3.65 [1.04; 6.26] |

27.95 [5.58; 50.32] |

2.00 [–2.40; 6.40] |

15.45 (0.83; 30.08] |

1.67 [–2.18; 5.51] |

14.00 [2.39; 25.61] |

2 | 1.00 [–11.71; 13.71] |

17.00 [–54.00; 88.00] |

| 19–24 years | 4.42 [2.92; 5.93] |

40.13 [28.29; 51.97] |

0.81 [–0.24; 1.85] |

15.06 [7.13; 22.98] |

1.13 [–0.33; 2.59] |

16.87 [8.35; 25.38] |

10.50 [–2.30; 23.30] |

3.33 [–0.52; 7.19] |

10.70 [–0.06; 21.46] |

| 25–29 years | 7.65 [5.29; 10.00] |

60.24 [37.34; 83.14] |

2.37 [0.33; 4.41] |

17.07 [6.94; 27.20] |

1.97 [0.11; 3.84] |

12.14 [6.18; 18.09] |

16.33 [–21.59; 54.26] |

9.53 [–1.33; 20.39] |

2.33 [0.57; 4.09] |

| 30–39 years | 6.10 [5.20; 7.00] |

44.31 [36.72; 51.90] |

2.71 [0.01; 5.42] |

19.54 [13.59; 25.49] |

1.90 [–0.66; 4.47] |

17.25 [12.42; 22.09] |

14.75 [–7.65; 37.15] |

3.57 [–2.30; 9.44] |

4.85 [1.61; 8.09] |

| 40–49 years | 5.95 [4.73; 7.16] |

40.91 [34.26; 47.57] |

1.40 [0.02; 2.78] |

13.68 [10.07; 17.28] |

0.60 [–0.11; 1.31] |

11.54 [8.59; 14.49] |

2.40 [–2.98; 7.78] |

0.37 [–0.23; 0.97] |

4.04 [2.00; 6.08] |

| 50–59 years | 3.67 [3.06; 4.28] |

33.53 [27.67; 39.40] |

1.56 [0.18; 2.95] |

11.01 [7.42; 14.60] |

0.48 [0.05; 0.92] |

11.55 [7.88; 15.22] |

8.60 [–13.22; 30.42] |

0.20 [–0.12; 0.52] |

2.98 [0.98; 4.98] |

| 60–69 years | 1.98 [1.54; 2.43] |

17.37 [12.86; 21.88] |

1.10 [–0.59; 2.80] |

2.43 [1.23; 3.63] |

1.41 [–0.44; 3.26] |

3.17 [1.37; 4.98] |

3.67 [–2.07; 9.40] |

2.14 [–2.49; 6.77] |

0.38 [–0.01; 0.76] |

| 70–79 years | 0.82 [0.44; 1.19] |

9.46 [4.85; 14.07] |

0.11 [–0.12; 0.33] |

5.19 [–0.06; 10.45] |

0.08 [–0.08; 0.24] |

6.67 [0.03; 13.30] |

2 | 0.40 [–0.71; 1.51] |

4.00 [–2.80; 10.80] |

| 80–100 years | 0 [0; 0] |

0.10 [–0.05; 0.26] |

0 [0; 0] |

4.17 [–4.24; 12.57] |

0 [0; 0] |

0 [0; 0] |

– | 0 [0; 0] |

0 [0; 0] |

*1Frequency during preceding month; *2frequencies during past year; 95% CI, 95% confidence interval of the mean

eTable 5a. Age specific data on the sexual practices of women (n = 1379).

|

Sexual practice ever undertaken % [95% CI] |

Vaginal intercourse n = 1312 |

Performed oral sex n = 1265 |

Received oral sex n = 1259 |

Anal intercourse, receptive n = 1272 |

| Age | ||||

| 14–18 years (n = 60) |

55.7 [42.3; 68.4] |

33.3 [22.0; 47.1] |

39.2 [27.0; 53.0] |

11.7 [5.6; 23.4] |

| 19–24 years (n = 78) |

93.4 [86.3; 96.9] |

68.9 [58.7; 77.5] |

73.0 [70.0; 81.1] |

22.4 [15.1; 32.2] |

| 25–29 years (n = 77) |

90.1 [82.2; 94.7] |

68.2 [57.8; 77.0] |

72.4 [62.2; 80.7] |

31.8 [23.0; 42.2] |

| 30–39 years (n = 160) |

94.1 [90.0; 96.6] |

66.8 [60.0; 73.0] |

69.7 [63.0; 75.8] |

30.3 [24.4; 37.0] |

| 40–49 years (n = 202) |

97.9 [95.2; 99.1] |

58.9 [52.4; 65.0] |

61.8 [55.4; 67.9] |

21.4 [16.6; 27.1] |

| 50–59 years (n = 226) |

97.6 [95.0; 98.9] |

48.2 [42.1; 54.4] |

53.2 [47.0; 59.3] |

16.3 [12.3; 21.4] |

| 60–69 years (n = 184) |

95.3 [91.4; 97.5] |

35.8 [29.3; 43.0] |

38.0 [31.3; 45.2] |

12.0 [8.1; 17.5] |

| 70–79 years (n = 114) |

92.1 [86.1; 95.6] |

18.7 [12.8; 26.5] |

22.1 [15.7; 30.3] |

6.5 [3.4; 12.3] |

| 80–100 years (n = 44) |

88.9 [77.8; 94.7] |

17.0 [9.3; 29.3] |

18.9 [10.6; 31.4] |

3.8 [1.2; 13.0] |

95% CI, 95% confidence interval of the mean

eTable 5b. Age specific data on the sexual practices of women (n = 1379).

|

Frequency Mean [95% CI] |

Vaginal intercourse | Performed oral sex | Received oral sex |

Anal intercourse, receptive |

|||

|

Vaginal intercourse *1 |

Vaginal intercourse *2 |

On men*2 | On men*2 |

Given by men*2 |

Given by women*2 |

Given by men*2 |

|

| Age | |||||||

| 14–18 years | 2.71 (1.31; 4.11] |

17.73 [10.58; 24.88] |

4.86 [0.32; 9.39] |

0.15 [–0.07; 0.38] |

4.94 [0.80; 9.08] |

0.25 [–0.06; 0.56] |

2.17 [–0.60; 4.94] |

| 19–24 years | 5.03 [3.65; 6.41] |

32.12 [25.58; 38.66] |

9.56 [5.19; 13.92] |

3.67 [–1.05; 8.38] |

12.26 [7.51; 17.02] |

3.56 [–0.58; 7.70] |

6.94 [0.39; 13.50] |

| 25–29 years | 6.12 [4.58; 7.66] |

46.72 [33.97; 59.48] |

14.93 [9.36; 20.50] |

4.73 [0.64; 8.81] |

18.73 [9.57; 27.90] |

2.55 [–1.02; 6.12] |

3.13 [1.22; 5.03] |

| 30–39 years | 5.24 [4.28; 6.20] |

40.79 [31.00; 50.57] |

11.82 [7.97; 15.67] |

4.05 [1.55; 6.55] |

12.15 [8.69; 15.61] |

2.45 [0.59; 4.32] |

7.37 [3.92;10.82] |

| 40–49 years | 3.94 [3.07; 4.81] |

31.60 [20.83; 42.36] |

8.70 [5.77; 11.63] |

3.18 [0.66; 5.69] |

8.68 [5.66; 11.70] |

2.78 [0.02; 5.53] |

4.36 [1.48; 7.24] |

| 50–59 years | 2.87 [2.26; 3.47] |

22.13 [16.04; 28.21] |

4.35 [2.08; 6.61] |

3.32 [1.10; 5.55] |

5.98 [3.47; 8.49] |

1.47 [0.16; 2.79] |

2.07 [0.31; 3.82] |

| 60–69 years | 1.55 [0.90; 2.20] |

13.72 [6.95; 20.49] |

4.17 [1.12; 7.23] |

0.43 [–0.26; 1.13] |

3.87 [1.35; 6.38] |

0.27 [–0.19; 0.74] |

1.74 [–0.06; 3.53] |

| 70–79 years | 0.41 [0.14; 0.69] |

1.69 [0.10; 3.27] |

0.33 [–0.23; 0.90] |

0.25 [–0.11; 0.61] |

0.73 [–0.69; 2.16] | 0.11 [–0.12; 0.35] |

2.57 [–3.72; 8.86] |

| 80–100 years | 0.29 [–0.19; 0.77] |

1.18 [–0.11; 2.47] |

0 [0; 0] |

0 [0; 0] |

0 [0; 0] |

0 [0; 0] |

0 |

*1Frequency during preceding month; *2frequencies during past year; 95% CI, 95% confidence interval of the mean

Acknowledgments

Translated from the original German by Birte Twisselmann, PhD.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that no conflict of interest exists.

References

- 1.Weltgesundheitsorganisation. Definition Sexuelle und reproduktive Gesundheit. www.euro.who.int/de/health-topics/Life-stages/sexual-and-reproductive-health/news/news/2011/06/sexual-health-throughout-life/definition (last accessed on 5 May 2017) [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization. www.who.int/reproductivehealth/topics/gender_rights/defining_sexual_health.pdf; 2006 (last accessed on 5 October 2016) Geneva: Defining sexual health. Report of a technical consultation on sexual health, 28-31 January 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chandra A, Copen CE, Mosher WD. Sexual behavior, sexual attraction, and sexual identity in the United States: data from the 2006-2010 National Survey of Family Growth. 2010;5:45–66. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Herbenick D, Reece M, Schick V, Sanders SA, Dodge B, Fortenberry JD. Sexual behavior in the United States: results from a national probability sample of men and women ages 14-94. J Sex Med. 2010;7:255–265. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2010.02012.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mercer CH, Tanton C, Prah P, et al. Changes in sexual attitudes and lifestyles in Britain through the life course and over time: findings from the National Surveys of Sexual Attitudes and Lifestyles (Natsal) Lancet. 2013;382:1781–1794. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62035-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kröger C. Sexuelle Außenkontakte und -beziehungen in heterosexuellen Partnerschaften. Psychol Rundsch. 2010;61:123–143. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Haversath J, Kröger C. Sexuelle Außenkontakte und deren Prädiktoren bei Homo- und Heterosexuellen. Psychother Psychosom Med Psychol. 2014;64:458–464. doi: 10.1055/s-0034-1390423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Robert Koch-Institut. Sechs Jahre STD-Sentinel Surveillance in Deutschland - Zahlen und Fakten. Epid Bull. 2010;3:20–27. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Robert Koch-Institut. Schätzung der Zahl der HIV-Neuinfektionen und der Gesamtzahl von Menschen mit HIV in Deutschland. Epid Bull. 2016;45:498–509. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Robert Koch-Institut. Weiterer verstärkter Anstieg von Syphilis-Infektionen bei Männern, die Sex mit Männern haben. Epid Bull. 2016;50:547–560. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gille G, Hampl M, Kreuter A, Klussmann J, Wojcinski M, Gross G. HPV-induzierte Kondylome, Karzinome und Vorläuferläsionen-eine interdisziplinäre Herausforderung. Dtsch med Wochenschr. 2014;139:2405–2410. doi: 10.1055/s-0034-1387373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wagenlehner FME, Brockmeyer NH, Discher T, Friese K, Wichelhaus TA. The presentation, diagnosis and treatment of sexually transmitted infections. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2016;113:11–22. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2016.0011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Marcus U. Risiken und Wege der HIV-Übertragung: Auswirkungen auf Epidemiologie und Prävention der HIV-Infektion. Bundesgesundheitsbl. 2000;43:449–458. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Johnson AM, Mercer CH, Erens B, et al. Sexual behaviour in Britain: partnerships, practices, and HIV risk behaviours. Lancet. 2001;358:1835–1842. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(01)06883-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Traeen B, Holmen K, Stigum H. Extradyadic sexual relationships in Norway. Arch Sex Behav. 2007;36:55–65. doi: 10.1007/s10508-006-9080-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bundeszentrale für gesundheitliche Aufklärung (BZgA) BZgA. 1. Köln: 2011. Repräsentativbefragungen Forschung und Praxis der Sexualaufklärung und Familienplanung. Verhütungsverhalten Erwachsener 2011: Aktuelle repräsentative Studie im Rahmen einer telefonischen Mehrthemenbefragung. [Google Scholar]

- 17.von Sydow K, Seiferth A. Sexualität in Paarbeziehungen. Praxis der Paar- und Familientherapie Band 8. Göttingen. Hogrefe. 2015 [Google Scholar]

- 18.Corsten C, von Rüden U. Prävention sexuell übertragbarer Infektionen (STI) in Deutschland. Bundesgesundheitsbl. 2013;56:262–268. doi: 10.1007/s00103-012-1600-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bremer V, Brockmeyer N, Coenenberg J. S1-Leitlinie STI/STD-Beratung, Diagnostik und Therapie (2015) www.awmf.org/uploads/tx_szleitlinien/059-006l_S1_STI_STD-Beratung_2015-07.pdf (last accessed on 7 March 2017) [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gross G, Becker N, Brockmeyer NH, et al. S3-Leitlinie Impfprävention HPV-assoziierter Neoplasien (2013) www.awmf.org/uploads/tx_szleitlinien/082-002k_Impfprävention_HPV_assoziierter_Neoplasien_2013-12.pdf (last accessed on 7 March 2017) [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bundeszentrale für politische Bildung. Datenreport 2016. Ein Sozialbericht für die Bundesrepublik Deutschland. www.destatis.de/DE/Publikationen/Datenreport/Downloads/Datenreport2016.pdf?__blob=publicationFile (last accessed on 25 February 2017) [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schöffer H. Sexuell übertragbare Infektionen der Mundhöhle. Hautarzt. 2012;63:710–715. doi: 10.1007/s00105-012-2352-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ständige Impfkommission (STIKO) Empfehlungen der Ständigen Impfkommission (STIKO) am Robert Koch-Institut 2016/2017. Epid Bull 2016 (Nr. 34 vom 29.08.2016) www.rki.de/DE/Content/Infekt/EpidBull/Archiv/2016/Ausgaben/34_16.pdf?__blob=publicationFile (last accessed on 5 May 2017) [Google Scholar]

- E1.Deutsche AIDS-Hilfe e. V., Schwule Männer und HIV/AIDS. Lebensstile, Sex, Schutz- und Risikoverhalten 2010. Eine Befragung im Auftrag der Bundeszentrale für gesundheitliche Aufklärung. www.ssoar.info/ssoar/bitstream/handle/document/34238/ssoar-2012-bochow_et_al-Schwule_Manner_und_HIVAIDS_.pdf?sequence=1 (last accessed on 25 February 2017) [Google Scholar]

- E2.Bode H, Heßling A. Bundeszentrale für gesundheitliche Aufklärung. Köln: 2015. Jugendsexualität 2015 Die Perspektive der 14- bis 25-Jährigen. Ergebnisse einer aktuellen repräsentativen Wiederholungsbefragung. [Google Scholar]

- E3.Dekker A, Matthiesen S. Studentische Sexualität im Wandel: 1966-1981-1996-2012. Z Sexualforsch. 2015;28:245–271. [Google Scholar]

- E4.Smith AMA, Rissel CE, Richters J, Grulich AE, de Visser RO. Sex in Australia: sexual identity, sexual attraction and sexual experience among a representative sample of adults. Aust N Z J Public Health. 2003;27:138–145. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-842x.2003.tb00801.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E5.Lewin B, Fugl-Meyer K, Helmius G. Sex in Sweden: about sexual life in Sweden, 1996. Natl Inst Pub Health. 1998 [Google Scholar]

- E6.Deleré Y, Remschmidt C, Leuschner J, et al. Human papillomavirus prevalence and probable first effects of vaccination in 20 to 25 year-old women in Germany: a population-based cross-sectional study via home-based self-sampling. BMC Infect Dis. 2014;14 doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-14-87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E7.Brotherton JM, Fridman M, May CL, et al. Early effect of the HPV vaccination programme on cervical abnormalities in Victoria, Australia: an ecological study. Lancet. 2011;377:2085–2092. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60551-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E8.Horn J, Damm O, Kretzschmar MEE, et al. Estimating the long-term effects of HPV vaccination in Germany. Vaccine. 2013;31:2372–2380. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2013.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E9.Yee L. Aging and sexuality. Australian Family Physician. 2010;39:718–721. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E10.Institut für Demoskopie Allensbach. JACOBS Krönung Studie mit der aktuellen Ausgabe. Partnerschaft 2012: Zwischen Herz und Verstand. Ergebnisse einer bevölkerungsrepräsentativen Befragung. www.jacobskroenung-studie.de/archiv#a-partnerschaft; 2012 (last accessed on 9 December 2013) [Google Scholar]

- E11.Vrangalova Z, Savin-Williams RC. Mostly heterosexual and mostly gay/lesbian: evidence for new sexual orientation identities. Arch Sex Behav. 2012;41:85–101. doi: 10.1007/s10508-012-9921-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E12.Whisman MA, Snyder DK. Sexual infidelity in a national survey of American women: differences in prevalence and correlates as a function of method of assessment. J Fam Psychol. 2007;21:147–154. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.21.2.147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E13.Kish L. A procedure for objective respondent selection within the household. JASA. 1949;44:380–387. [Google Scholar]

- E14.Terman L, Butterwieser P, Ferguson LW, Johnson WB, Wilson DP. McGraw-Hill. New York: 1938. Psychological factors in marital happiness. [Google Scholar]