The mammalian innate immune system provides the first line of defensive mechanisms to protect the host against invading pathogens. These defensive responses are initiated by recognition of microbial pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs), which are engaged by conserved germline-encoded pattern recognition receptors (PRRs).1 Viral infection is always a considerable threat for public health. During viral infection, viral nucleic acids serve as the dominant PAMPs for the host innate immune system, which can be recognized by diverse PRR families, including Toll-like receptors (TLRs), RIG-I-like receptors and cytosolic DNA receptors. Viral nucleic acid sensing markedly triggers downstream type I interferon secretion, which thereby activates interferon-stimulated genes to exert anti-viral effects.2

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) is a dangerous human pathogen that infects over 170 million individuals worldwide. HCV infection easily develops into a persistent infection, leading to liver cirrhosis or even hepatocellular carcinoma.3 HCV is an enveloped, positive-sense single-stranded RNA virus. The genome of HCV encodes structural proteins (core, E1 and E2) and nonstructural proteins (p7, nonstructural (NS) 2, NS3, NS4A, NS4B, NS5A and NS5B). During HCV infection, viral dsRNA replicative intermediates can be recognized by RIG-I and MDA5 to induce a type I IFN response, which is crucial for the host to counteract HCV infection.4, 5

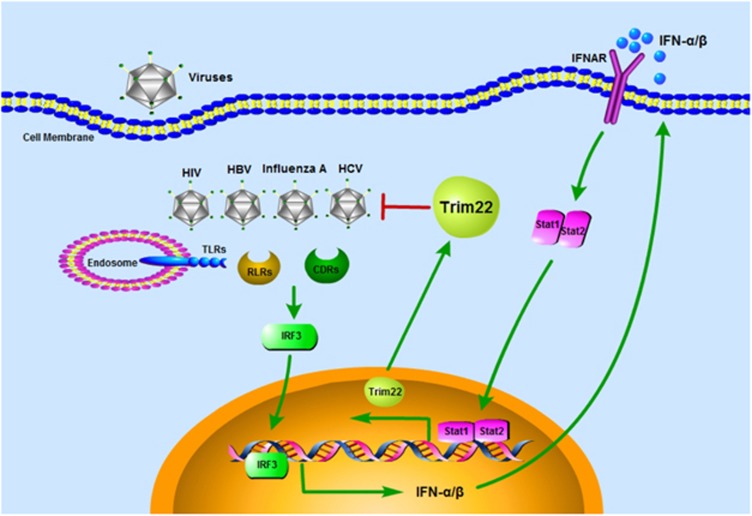

The tripartite motif (TRIM) family is a well-known superfamily with Ring-finger E3 ubiquitin ligase activity. The TRIM family includes greater than 70 members in humans. TRIM family members have been implicated as critical regulators of innate immune responses against microbial pathogens, including anti-viral responses.6, 7 Virus recognition-triggered type I interferon could subsequently induce numerous TRIM proteins expression, which are crucial for restricting viral infection via either regulating innate signaling pathways or serving as viral restriction factors.8 Trim22 is a typical TRIM family protein that restricts the replication of various viruses via distinct manners, for example, inhibiting HIV particle production,9 suppressing the activity of hepatitis B virus core promoter10 and targeting influenza A virus nucleoprotein for degradation.11 In our previous work, Yang et al.12 identified the anti-viral role of trim22 on the inhibition of HCV replication (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Trim22 is a broad anti-viral host factor. During virus infection, including HIV, HBV, influenza A virus and HCV, viral nucleic acids are detected by host PRRs (such as TLR3/7/8/9, RIG-I/MDA5, cGAS/DDX41/IFI16). Recognition of viral DNA/RNA triggers type I interferon production dependent on IRF3 activation. Secreted IFN-α/β bind to IFNAR to activate the Stat1-Stat2 heterodimer to induce the expression of trim22, a critical viral restriction factor, protecting the host against diverse viral infections.

Trim22 is an IFN-inducible protein that is induced by IFN-α and IFN-γ in HepG2 cells, an epithelial-like human liver carcinoma cell line.10 Yang et al. validated the inducible expression of trim22 by IFN-α in Huh-7 cells. The authors presented a direct induction of trim22 by HCV infection after 24 h in Huh-7 cells; however, the upregulation of trim22 was lower than that noted with IFN treatment. In addition, the study demonstrated that trim22 was significantly induced in PBMCs of HCV-infected patients following IFN-α treatment. In addition, trim22 expression peaked at 12 h post IFN-α treatment, suggesting a potential role of trim22 in IFN-α-mediated anti-HCV therapy.

Using a reconstructed Huh-7 cell line stably expressing the HCV Con1 replicon genome, the authors assessed the anti-HCV activity of trim22. Overexpression of trim22 markedly inhibited HCV NS5A protein levels and HCV replicon levels, and trim22 knockdown greatly enhanced HCV replication activity that occurred upon IFN treatment but not at steady state.

Assessment of the mechanism indicated that trim22 directly interacted with NS5A. NS5A is an HCV nonstructural protein that is critical for both HCV replication and assembly.13 The crosstalk of host factors and viral factors is a consequence of co-evolution. Viral factors typically target host factors to avoid immune sensing or immune clearance. Conversely, many host factors can also bind to viral factors to restrict viral replication. NS5A targets Myd88 to attenuate TLR signaling and interacts with PKR to interfere with HCV RNA replication.13 However, few host factors have been identified as targeting NS5A. Here Yang et al. identified interactions with trim22 and NS5A via SPRY domain and domain 1, respectively. The interaction rendered trim22 as an ubiquitin ligase of NS5A. Overexpression of trim22 specifically decreased NS5A protein levels rather than other HCV structural or nonstructural proteins. Moreover, endogenous NS5A could be ubiquitinated by trim22. IFN treatment induced ubiquitination of endogenous NS5A. However, the authors did not map the ubiquitination type and ubiquitination site of NS5A by E3 ligase trim22, which is crucial to understand the regulatory mechanism of trim22 on HCV infection. Overall, the study provides molecular insights to better understand IFN-α-mediated HCV infection therapy.

Some important questions that arise from this study should be further explored. What is the restriction activity of trim22 against HCV infection? The present trim22-mediated inhibition activity of HCV replication was determined by a Huh-7-Con1-rep cell system rather than direct HCV infection. Thus, whether trim22 indeed restricts HCV virus infection in vivo remains to be further validated. Another important question involves evaluating trim22 expression levels in healthy donors and HCV-infected patients to determine whether HCV infection induces trim22 upregulation in vivo. Following this study, another group confirmed the protective role of trim22 against HCV and uncovered the clinical significance of trim22 for IFN-α-mediated HCV therapy. Medrano et al. analyzed whether single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) at TRIM22 and TRIM5 genes were associated with liver fibrosis and response to IFN-α plus ribavirin therapy in HIV/HCV co-infected patients. The TRIM22 rs1063303 GG genotype is a sensitive SNP for liver fibrosis in HIV/HCV co-infected patients.14

Notably, trim22 is crucial for the restriction of infection by diverse viruses, including HIV, influenza A virus, HBV, herpesvirus15 and HCV (Figure 1). Among these viruses, HIV, HBV and HCV infections are associated with special TRIM22 SNPs in the clinic.14 The reported viruses targeted by trim22 vary from RNA viruses to DNA viruses and single-strand viruses to double-strand viruses, displaying little specificity. More interestingly, trim22 restricts the infection of these viruses through largely distinct mechanisms. Hence, trim22 is a broad and multifunctional host anti-viral factor induced by interferons.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Broz P, Monack DM. Newly described pattern recognition receptors team up against intracellular pathogens. Nat Rev Immunol 2013; 13: 551–565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan N, Chen ZJ. Intrinsic antiviral immunity. Nat Immunol 2012; 13: 214–222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavanchy D. The global burden of hepatitis C. Liver Int 2009; 29: 74–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hei L, Zhong J. Laboratory of genetics and physiology 2 (LGP2) plays an essential role in hepatitis C virus infection-induced interferon responses. Hepatology 2017; 65: 1478–1491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao X, Ding Q, Lu J, Tao W, Huang B, Zhao Y et al. MDA5 plays a critical role in interferon response during hepatitis C virus infection. J Hepatol 62: 771–778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawai T, Akira S. Regulation of innate immune signalling pathways by the tripartite motif (TRIM) family proteins. EMBO Mol Med 2011; 3: 513–527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Versteeg Gijs A, Rajsbaum R, Sánchez-Aparicio Maria T, Maestre Ana M, Valdiviezo J, Shi M et al. The E3-ligase TRIM family of proteins regulates signaling pathways triggered by innate immune pattern-recognition receptors. Immunity 2013; 38: 384–398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ozato K, Shin D-M, Chang T-H, Morse HC. TRIM family proteins and their emerging roles in innate immunity. Nat Rev Immunol 2008; 8: 849–860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barr SD, Smiley JR, Bushman FD. The Interferon Response Inhibits HIV Particle Production by Induction of TRIM22. PLoS Pathog 2008; 4: e1000007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao B, Duan Z, Xu W, Xiong S. Tripartite motif-containing 22 inhibits the activity of hepatitis B virus core promoter, which is dependent on nuclear-located RING domain. Hepatology 2009; 50: 424–433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Pietro A, Kajaste-Rudnitski A, Oteiza A, Nicora L, Towers GJ, Mechti N et al. TRIM22 inhibits influenza A virus infection by targeting the viral nucleoprotein for degradation. J Virol 2013; 87: 4523–4533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang C, Zhao X, Sun D, Yang L, Chong C, Pan Y et al. Interferon alpha (IFN[agr])-induced TRIM22 interrupts HCV replication by ubiquitinating NS5A. Cell Mol Immunol 2016; 13: 94–102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong M-T, Chen SSL. Emerging roles of interferon-stimulated genes in the innate immune response to hepatitis C virus infection. Cell Mol Immunol 2016; 13: 11–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medrano LM, Rallón N, Berenguer J, Jiménez-Sousa MA, Soriano V, Aldámiz-Echevarria T et al. Relationship of TRIM5 and TRIM22 polymorphisms with liver disease and HCV clearance after antiviral therapy in HIV/HCV coinfected patients. J Transl Med 2016; 14: 257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Renne R, Barry C, Dittmer D, Compitello N, Brown PO, Ganem D. Modulation of cellular and viral gene expression by the latency-associated nuclear antigen of kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus. J Virol 2001; 75: 458–468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]