Abstract

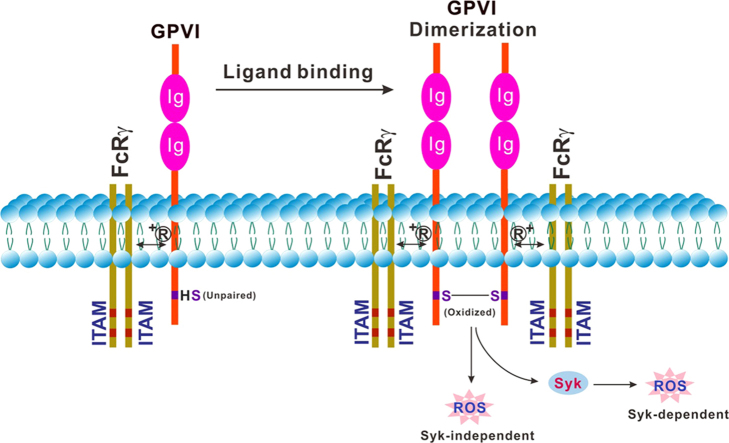

Reactive oxygen species (ROS) are generated within activated platelets and play an important role in regulating platelet responses to collagen and collagen-mediated thrombus formation. As a major collagen receptor, platelet-specific glycoprotein (GP)VI is a member of the immunoglobulin (Ig) superfamily, with two extracellular Ig domains, a mucin domain, a transmembrane domain and a cytoplasmic tail. GPVI forms a functional complex with the Fc receptor γ-chain (FcRγ) that, following receptor dimerization, signals via an intracellular immunoreceptor tyrosine-based activation motif (ITAM), leading to rapid activation of Src family kinase signaling pathways. Our previous studies demonstrated that an unpaired thiol in the cytoplasmic tail of GPVI undergoes rapid oxidation to form GPVI homodimers in response to ligand binding, indicating an oxidative submembranous environment in platelets after GPVI stimulation. Using a redox-sensitive fluorescent dye (H2DCF-DA) in a flow cytometric assay to measure changes in intracellular ROS, we showed generation of ROS downstream of GPVI consists of two distinct phases: an initial Syk-independent burst followed by additional Syk-dependent generation. In this review, we will discuss recent findings on the regulation of platelet function by ROS, focusing on GPVI-dependent platelet activation and thrombus formation.

Keywords: Platelet activation, Thrombus formation, GPVI, ROS

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

Rapid oxidation of thiol in the tail of GPVI in response to ligand binding.

-

•

Generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) downstream of GPVI.

-

•

GPVI-mediated ROS generation consists of syk-independent and syk-dependent phase.

-

•

Important role of ROS in GPVI-dependent platelet activation and thrombus formation.

1. Introduction

As natural by-products of aerobic metabolism, reactive oxygen species (ROS) are comprised of radical and non-radical oxygen species formed by the partial reduction of oxygen, including superoxide anion (O2• ‒), hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), and hydroxyl radical (HO•) [1]. ROS are generated endogenously in response to stimulation by cytokines, xenobiotics and bacterial invasion as well as during mitochondrial oxidative metabolism [2]. Abnormal elevation of ROS is associated with oxidative stress, and implicated in diseases such as atherosclerosis [3], diabetes [4] and, neurodegeneration [5] as well as in aging [6], resulting in potential damage to proteins, lipids and nucleic acids.

In recent years, there is increasing evidence demonstrating that ROS also regulate cellular signaling pathways involved in physiological and pathological processes [7]., [8].. One potential mechanism for how ROS regulate signaling pathways is through oxidation of cysteine (Cys) residues on signaling proteins [9]. ROS also regulate the function of anucleate blood platelets [10]., [11]., [12]., and the use of antioxidants in the prevention and treatment of thrombotic or cardiovascular diseases has been investigated [13]., [14].. One important pathway for generating intracellular ROS in human platelets is through ligand binding to the platelet collagen receptor, glycoprotein (GP)VI [15]. In this review, we will discuss recent findings on the role of ROS in regulating GPVI-dependent platelet activation and thrombus formation.

2. Platelet adhesion, activation and thrombus formation

At sites of vascular injury, platelets roll, adhere and firmly attach to subendothelial matrix by platelet primary membrane receptors, glycoprotein (GP)VI which binds collagen, and GPIbα, the major ligand-binding subunit of GPIb-IX-V complex, which binds von Willebrand factor (VWF) and other ligands, through recognition of exposed VWF/collagen in the damaged blood vessel wall, initiating platelet adhesion and triggering rapid activation [16]., [17].. Activation of signaling pathways lead to cytoskeletal rearrangements, shape change and activation of the platelet integrin, αIIbβ3, from a low- to a high-affinity state which binds ligands including fibrinogen, VWF, fibronectin and vitronectin [18]., [19].. Activated platelets secrete platelet agonists, such as adenosine diphosphate (ADP) and thromboxane A2 (TXA2) which bind to purinergic (P2Y) receptors and thromboxane receptor (TP), respectively, to reinforce αIIbβ3-dependent platelet aggregation [19]. Further, along with a number of other cell types, platelets express surface CD40 ligand (CD40L; also known as CD154) a molecule that is crucial for cell signaling in both adaptive and innate immunity. On activated platelets, CD40L can be cleaved by metalloproteinases into a soluble form [20]. The majority (> 95%) of plasma soluble CD40L (sCD40L) is derived from platelets [20] and sCD40L enhances platelet activation in an auto-amplification loop [21], leading to heightened platelet aggregation and platelet-leukocyte interactions. These interactions have been implicated in the onset of atherothrombosis [22]., [23]. and arterial hypertension [24]. This process involves signaling via tissue necrosis factor-α receptor associated factor (TRAF) 6, which is emerging as a molecular target that can be therapeutically modulated in a range of disorders [25]., [26].. Furthermore, activated platelets also promote coagulation by surface expression of phosphatidylserine (PS) and release of procoagulant factors that lead to thrombin generation and fibrin formation. In particular, GPVI and GPIb-IX-V are crucial in the initiation of platelet thrombus formation under abnormal pathological shear stress and altered blood flows, for example within stenosed arteries, and also play an important role in initiating thrombus formation in experimental models of cerebral vascular stroke [27]., [28]., [29]., [30]..

3. Platelet GPVI: expression, shedding and generation of intracellular ROS

GPVI is a type I transmembrane receptor and a member of the immunoglobulin (Ig)-like superfamily, only expressed on platelets and megakaryocytes, and consisting of two extracellular Ig domains, a short mucin-like domain, a transmembrane domain and a cytoplasmic tail [31]. The major physiological ligand for platelet GPVI is collagen, although laminin and fibrin have also been identified as GPVI ligands [32]., [33]., [34]., [35].. In addition, several nonphysiological ligands have been described, including cross-linked collagen-related peptide (CRP) [36], snake toxins (convulxin, alborhagin, crotarhagin) [37]., [38]., [39]. and anti-GPVI antibodies [40]. The GPVI cytoplasmic domain contains binding sites for calmodulin (CaM) via a membrane-proximal positively-charged sequence [41]., [42]., and for Src family kinases (Fyn and Lyn) via a proline-rich sequence and involved in GPVI-dependent signal transduction [43]. GPVI is also co-associated with the Fc receptor γ-chain (FcRγ), required for GPVI surface expression [31]., [36].. Binding of multivalent ligands and cross-linking of GPVI/FcRγ leads to phosphorylation of an immunoreceptor tyrosine-based activation motif (ITAM) within the cytoplasmic tail of FcRγ by the Src family kinase, Lyn, in turn resulting in recruitment and assembly of spleen tyrosine kinase (Syk) and subsequent activation of various adaptor proteins, such as 76-kDa tyrosine phosphoprotein (SLP-76) and Linker-for-activation of T cells (LAT), eventually resulting in the activation of phospholipase Cγ2 (PLCγ2). PLCγ2 causes elevation of cytosolic Ca2+ and leads to activation of integrin αIIbβ3 [44]., [45]..

Another important consequence of ligand binding to GPVI is dissociation of CaM from the cytoplasmic tail of GPVI, and subsequent metalloproteinase (ADAM10)-mediated GPVI ectodomain shedding, generating a soluble extracellular fragment (sGPVI) and a membrane-associated remnant fragment [46]., [47]., [48].. In human plasma, sGPVI represents a platelet-specific marker of platelet function, and is elevated in athero-thrombotic, inflammatory and immune-related disorders. Interestingly, ligand binding to GPVI also causes rapid transient disulfide-dependent receptor dimerization through oxidation of the Cys residue in the GPVI cytoplasmic tail [49], suggesting an oxidative submembranous environment in activated platelets [50]., [51]..

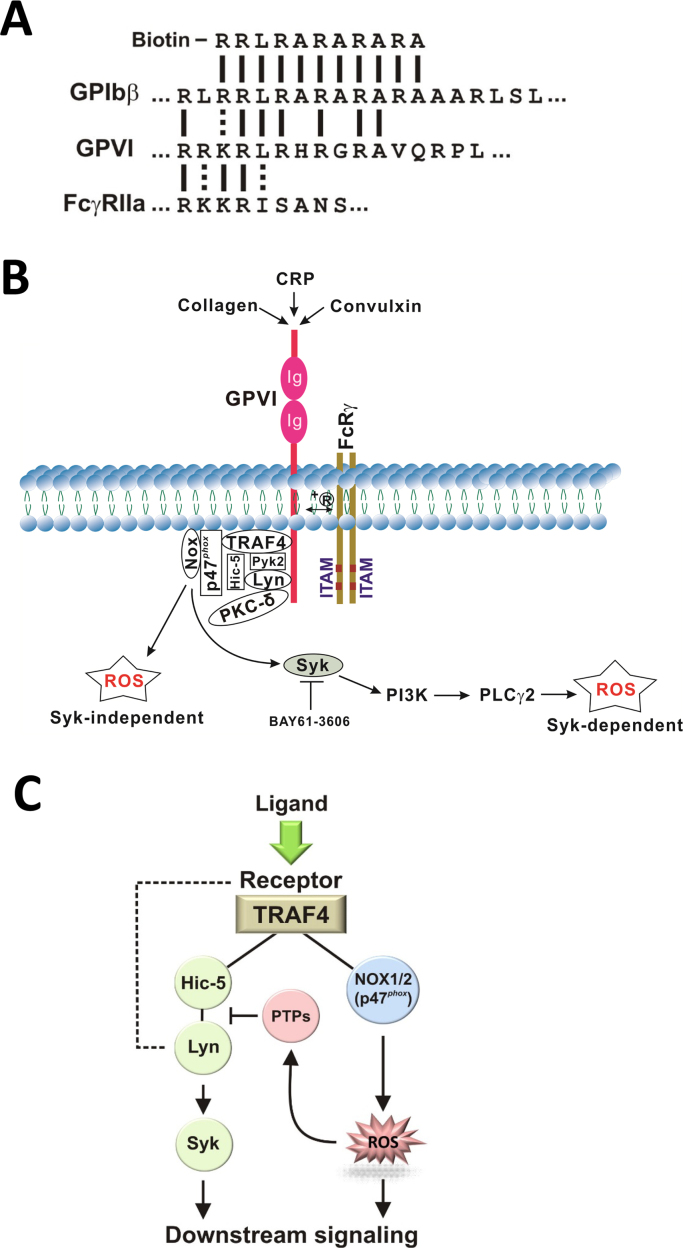

Healthy human platelets contain basal levels of intracellular ROS, however these levels rapidly increase following GPVI stimulation [10]., [52]., [53]., [54]., [55].. Unique evidence for the mechanism by which engagement of GPVI may generate oxidative stress was provided in recent studies identifying tumor necrosis factor receptor associated factor (TRAF4) as a novel binding partner for GPVI (Fig. 1A), using a biotinylated amino acid sequence based on calmodulin-binding sequences of GPVI, GPIbβ and FcγRIIa [56]. TRAF4 selectively binds to the cytoplasmic tail of GPVI and interacts with p47phox, a subunit of the NADPH oxidase 1 and 2 (NOX1/2) complex, which is the major source of ROS production in platelets. In addition, TRAF4 also interacts with other signaling proteins such as Pyk2 and Hic-5, which are constitutively associated with Lyn, a key component of the GPVI-dependent signaling pathway. In platelets, Lyn is associated with protein kinase C (PKC) δ and phosphorylates PKC-δ in human platelets stimulated with the GPVI agonist, convulxin [57]. As PKC-δ is required for p47phox phosphorylation and subsequent translocation to the membrane [58], TRAF4 directly associated with the cytoplasmic region of GPVI (or another receptor) could link Lyn (via Hic-5 and Pyk2), PKC-δ (via Lyn) and NOX1/2 (via p47phox) upon GPVI engagement. This would trigger p47phox phosphorylation and subsequent activation of NOX1/2, thereby activating downstream Syk-dependent or Syk-independent pathways leading to platelet aggregation (Fig. 1B). Intraplatelet ROS may also activate cytosolic protein tyrosine phosphatases (PTPs) to negatively regulate Hic-5/Lyn (Fig. 1C). For example, ROS can reversibly inactivate phosphorylation-dependent signaling by oxidation of an active site cysteine in PTPs such as SHP-2 [12]., [59]., allowing Lyn-dependent signaling to occur. Deficiency of peroxiredoxin II, an antioxidant enzyme, enhanced GPVI-mediated platelet activation, possibly through the defective elimination of H2O2 and/or impaired protection of SHP-2 against oxidative inactivation, leading to increased tyrosine phosphorylation of key components for Syk-dependent pathway of GPVI signaling [60]. Peroxiredoxin II-deficient platelets also displayed increased adhesion/aggregation upon collagen stimulation. These interactions involving both redox and tyrosine phosphorylation pathways provide a mechanism for rapid initiation of downstream signaling by platelets in response to ligands acting at GPIb-IX-V/GPVI (VWF/collagen). Interestingly, given the common binding sequence on GPVI for both TRAF4 and calmodulin (Fig. 1A), it is not yet proven whether binding of these proteins to this site is mutually exclusive. However, if calmodulin competes with TRAF binding, then dissociation of calmodulin promoting receptor shedding could provide a mechanism to limit ligand-induced GPVI-dependent ROS production via TRAF4/NOX. Further studies are needed to test this possibility.

Fig. 1.

(A) Calmodulin-binding sequences in platelet receptors. Positively-charged lysine (K)- and arginine (R)-rich calmodulin-binding sequences of GPIbβ, GPVI and FcγRIIa, and the biotinylated amino acid sequence used to identify TRAF4 as a potential receptor-binding partner (solid lines indicate identical residues, dotted line conservative substitutions). (B) ROS generation downstream of GPVI signaling. TRAF4 and its binding partner p47phox (NOX1/2 subunit) are constitutively associated with the cytoplasmic tail of GPVI, providing a link of ROS generation to downstream signaling in response to ligand binding (such as CRP, collagen or convulxin) via Src family kinase Lyn, which is constitutively bound to GPVI as well as to TRAF4-binding partners Pyk2 and Hic-5, and PKC-δ, which is associated with Lyn, resulting in phosphorylation of PKC-δ. Once activated, PKC-δ regulates p47phox phosphorylation, translocation and NOX activation. Two distinct Syk-independent and Syk-dependent phases of ROS generation occur after GPVI ligation, distinguishable using a Syk inhibitor such as BAY61-3606. (C) Overview of potential link between platelet receptors, TRAF4 and redox complexes. TRAF4 directly associated with the cytoplasmic region of GPVI or other receptors could link these receptors to Lyn (via Hic-5) and NOX (via p47phox), thereby activating downstream Syk-dependent or Syk-independent pathways leading to platelet aggregation. ROS may also activate cytosolic protein tyrosine phosphatase (PTPs) to negatively regulate Hic-5/Lyn. Hic-5 can also bind Pyk2 (panel B). Phosphorylated Lyn is also directly associated with GPVI (dashed line). See the text for details.

There is abundant evidence supporting the importance of platelet ROS in platelet function and in human health and disease. Higher levels of platelet ROS are associated with thrombotic diseases, hypertension, diabetes, hypercholesterolemia and metabolic syndrome [61]. ROS may also be involved in other pathways controlling platelet activation [62]. Catalase-induced reduction of cytosolic H2O2 impaired platelet aggregation [63]. Platelets treated with NOX inhibitors (see below), or platelets from patients with X-linked chronic granulomatous disease that are genetically deficient in the catalytic NOX subunit gp91phox, also exhibited decreased intracellular Ca2+ mobilization and platelet activation [64]. In addition, ROS scavengers or inhibitors of O2• ‒ production, apocynin and catalase, attenuated platelet activation, whereas ROS donors such as 2,3-dimethoxy-1,4-naphthoquinone (DNMQ) enhanced platelet activation [64]. Furthermore, a recent study has demonstrated a role for isoprostanes, produced by oxidation of arachidonic acid, in platelet activation and thrombus growth [64], whereas pharmacologic antioxidants, such as vitamin C, vitamin E or transresveratrol, can inhibit platelet activation and aggregation [11].

4. Potential therapeutic targeting of ROS in platelets

Targeting components of ROS generation including subunits of NOX1/2 in platelets is an appealing strategy, although this requires increased understanding of precise mechanisms, as global targeting of NOX activity for example could have potentially deleterious effects in cells other than platelets. Improved targeting could involve selective blockade of receptor-localizing elements of NOX complexes, thereby inhibiting ligand-induced ROS production by platelet-specific receptors such as GPIb-IX-V or GPVI/FcRγ, and/or enabling the uncoupling of ROS burst following platelet exposure to VWF/collagen essential for thrombus formation at high arterial shear rates.

Inhibition of NOX activity using NOX inhibitors, diphenylene-iodoniumchloride (DPI) and apocynin, significantly impeded platelet activation, aggregation and thrombus formation [10]., [53].. There are 7 NOX family members (NOX1-5 and DUOX1-2) identified in mammalian cells [65]., [66]., [67].. Expression of both NOX1 and NOX2 has been confirmed in both human and mouse platelets [68]., [69].. Studies using a pharmacological inhibitor specific for NOX1, ML171 (2-acetylphenothiazine) as well as NOX2-deficient mice [70] have shown that NOX1, but not NOX2, is responsible for GPVI-dependent ROS production and TXA2 generation, mediated in part through p38 MAP kinase-dependent signaling. Both NOX1 and NOX2 are required for collagen-mediated thrombus formation at arterial shear. Other evidence suggests that NOX1 is selectively important in G protein coupled receptor-mediated platelet activation induced by thrombin, but is not required for GPVI-dependent platelet activation induced by CRP in mice [69]. Furthermore, NOX2-/- platelets displayed reduced ROS generation and Ca2+ mobilization during GPVI-dependent platelet activation. Additional selective inhibitors and accounting for likely differences between human and mouse platelets are required to define the relative role of NOX1/2 in GPVI-dependent ROS production under different patho-physiological conditions.

GPVI-dependent generation of intracellular ROS in human platelets measured using the redox-sensitive fluorescent dye, H2DCF-DA, was not affected by inhibitors of αIIbβ3 (abciximab, GRGDSP peptide) or Src family kinases (PP1, PP2), but strongly inhibited by an inhibitor of NOX (apocynin) [15]. Inhibitors of PI3K (LY294002) or Syk (piceatannol, BAY61-3606) partially inhibited ROS generation. In this regard, approximately one-third of total GPVI-dependent ROS occurred within 2 min (ROSinitial), without further ROS generation in the presence of BAY61-3606 or piceatannol, suggesting the Syk-dependent pathways are not required for the initial burst of ROS, but are involved in subsequent ROS generation, and consistent with an initial Syk-independent burst and an additional Syk-dependent phases of GPVI-dependent ROS generation (Fig. 1B). Consistently, two distinct phases of ROS formation were also observed in analyses of single mitochondria ROS production, termed ROS-induced ROS release (RIRR), representing the initial or triggering phase followed by a subsequent amplification of ROS release [71]. In addition, RIRR in smooth muscle cells was also reported to be via NOX activation [72]. Moreover, in angiotensin-II treated endothelial cells, ROS generation resulting from angiotensin-II-mediated NOX activation decreased the mitochondrial membrane potential, leading to mitochondrial ROS formation and subsequent activation of PKC, and enhanced activation of NOX, resulting in increased intracellular ROS production [73]. Further supporting the role of mitochondrial ROS in NOX activation, angiotensin-II-induced activation of NOX was reduced in vascular smooth muscle cells where mitochondrial function had been ablated [74]. Mitochondrial ROS also induces NOX activation in human leukocytes and increased NOX activity was observed in mice with mitochondrial superoxide dismutase deficiency [75]. Taken together, these studies suggest a functionally relevant crosstalk between NOX and mitochondria exist [76]., [77]., [78].. However, whether mitochondria play a significant role in the subsequent ROS generation in GPVI-stimulated platelets remains unclear and requires further investigation.

5. Conclusion

Engagement of primary platelet receptors, GPIb-IX-V and GPVI, that initiate thrombus formation at arterial shear rates leads to a rapid increase in intracellular ROS above basal levels, and is a key step in platelet activation following exposure to physiological ligands, VWF/collagen. Targeting linkage of these or other receptors to ROS-generating NOX1/2 complexes via the adaptor, TRAF4, could provide far greater selective inhibition of ROS generation/platelet reactivity than general antioxidant treatment. Understanding the basic mechanisms underpinning receptor-linked ROS in human platelets is critical, and could ultimately enable maintenance of optimal platelet intracellular ROS levels in disease states associated with exacerbated thrombotic propensity.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant no. 81400082, 81370602 and 81570096), the Natural Science Foundation of Jiangsu Province (grant no. BK20140219), the funding for the Distinguished Professorship Program of Jiangsu Province, the Six Talent Peaks Project of Jiangsu Province (WSN-133), the Shuangchuang Project of Jiangsu Province, the 333 Project of Jiangsu Province (BRA2017542), the Scientific Research Foundation for the Returned Overseas Chinese Scholars, State Education Ministry, the Science and Technology Foundation for the Selected Overseas Chinese Scholars, State Ministry of Human Resources and Social Security, and the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia.

Contributor Information

Jianlin Qiao, Email: jianlin.qiao@gmail.com.

Kailin Xu, Email: lihmd@163.com.

References

- Ray P.D., Huang B.W., Tsuji Y. Reactive oxygen species (ROS) homeostasis and redox regulation in cellular signaling. Cell Signal. 2012;24:981–990. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2012.01.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andreyev A.Y., Kushnareva Y.E., Starkov A.A. Mitochondrial metabolism of reactive oxygen species. Biochemistry. 2005;70:200–214. doi: 10.1007/s10541-005-0102-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forstermann U., Xia N., Li H. Roles of vascular oxidative stress and nitric oxide in the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis. Circ. Res. 2017;120:713–735. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.116.309326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maritim A.C., Sanders R.A., Watkins J.B., 3rd Diabetes, oxidative stress, and antioxidants: a review. J. Biochem. Mol. Toxicol. 2003;17:24–38. doi: 10.1002/jbt.10058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X., Guo C., Kong J. Oxidative stress in neurodegenerative diseases. Neural Regen. Res. 2012;7:376–385. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1673-5374.2012.05.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haigis M.C., Yankner B.A. The aging stress response. Mol. Cell. 2010;40:333–344. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finkel T. Signal transduction by reactive oxygen species. J. Cell Biol. 2011;194:7–15. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201102095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown D.I., Griendling K.K. Regulation of signal transduction by reactive oxygen species in the cardiovascular system. Circ. Res. 2015;116:531–549. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.116.303584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhee S.G. Cell signaling. H2O2, a necessary evil for cell signaling. Science. 2006;312:1882–1883. doi: 10.1126/science.1130481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Begonja A.J., Gambaryan S., Geiger J., Aktas B., Pozgajova M., Nieswandt B. Platelet NAD(P)H-oxidase-generated ROS production regulates alphaIIbbeta3-integrin activation independent of the NO/cGMP pathway. Blood. 2005;106:2757–2760. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-03-1047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krotz F., Sohn H.Y., Pohl U. Reactive oxygen species: players in the platelet game. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2004;24:1988–1996. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000145574.90840.7d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jang J.Y., Min J.H., Chae Y.H., Baek J.Y., Wang S.B., Park S.J. Reactive oxygen species play a critical role in collagen-induced platelet activation via SHP-2 oxidation. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2014;20:2528–2540. doi: 10.1089/ars.2013.5337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nunez-Cordoba J.M., Martinez-Gonzalez M.A. Antioxidant vitamins and cardiovascular disease. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 2011;11:1861–1869. doi: 10.2174/156802611796235143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goszcz K., Deakin S.J., Duthie G.G., Stewart D., Leslie S.J., Megson I.L. Antioxidants in cardiovascular therapy: panacea or false hope? Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2015;2:29. doi: 10.3389/fcvm.2015.00029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arthur J.F., Qiao J., Shen Y., Davis A.K., Dunne E., Berndt M.C. ITAM receptor-mediated generation of reactive oxygen species in human platelets occurs via Syk-dependent and Syk-independent pathways. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2012;10:1133–1141. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2012.04734.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiao J.L., Shen Y., Gardiner E.E., Andrews R.K. Proteolysis of platelet receptors in humans and other species. Biol. Chem. 2010;391:893–900. doi: 10.1515/BC.2010.081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrews R.K., Gardiner E.E., Shen Y., Whisstock J.C., Berndt M.C. Glycoprotein Ib-IX-V. Int. J. Biochem. Cell. Biol. 2003;35:1170–1174. doi: 10.1016/s1357-2725(02)00280-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hynes R.O. Integrins: versatility, modulation, and signaling in cell adhesion. Cell. 1992;69:11–25. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90115-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Z., Delaney M.K., O'Brien K.A., Du X. Signaling during platelet adhesion and activation. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2010;30:2341–2349. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.110.207522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andre P., Prasad K.S., Denis C.V., He M., Papalia J.M., Hynes R.O. CD40L stabilizes arterial thrombi by a beta3 integrin--dependent mechanism. Nat. Med. 2002;8:247–252. doi: 10.1038/nm0302-247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aloui C., Prigent A., Sut C., Tariket S., Hamzeh-Cognasse H., Pozzetto B. The signaling role of CD40 ligand in platelet biology and in platelet component transfusion. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2014;15:22342–22364. doi: 10.3390/ijms151222342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antoniades C., Bakogiannis C., Tousoulis D., Antonopoulos A.S., Stefanadis C. The CD40/CD40 ligand system: linking inflammation with atherothrombosis. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2009;54:669–677. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.03.076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pamukcu B., Lip G.Y., Snezhitskiy V., Shantsila E. The CD40-CD40L system in cardiovascular disease. Ann. Med. 2011;43:331–340. doi: 10.3109/07853890.2010.546362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hausding M., Jurk K., Daub S., Kroller-Schon S., Stein J., Schwenk M. CD40L contributes to angiotensin II-induced pro-thrombotic state, vascular inflammation, oxidative stress and endothelial dysfunction. Basic Res. Cardiol. 2013;108:386. doi: 10.1007/s00395-013-0386-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu H., Arron J.R. TRAF6, a molecular bridge spanning adaptive immunity, innate immunity and osteoimmunology. Bioessays. 2003;25:1096–1105. doi: 10.1002/bies.10352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu H., Tamashiro S., Baritaki S., Penichet M., Yu Y., Chen H. TRAF6 activation in multiple myeloma: a potential therapeutic target. Clin. Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2012;12:155–163. doi: 10.1016/j.clml.2012.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falk E., Nakano M., Bentzon J.F., Finn A.V., Virmani R. Update on acute coronary syndromes: the pathologists' view. Eur. Heart J. 2013;34:719–728. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehs411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davi G., Patrono C. Platelet activation and atherothrombosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2007;357:2482–2494. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra071014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroll M.H., Hellums J.D., McIntire L.V., Schafer A.I., Moake J.L. Platelets and shear stress. Blood. 1996;88:1525–1541. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleinschnitz C., Pozgajova M., Pham M., Bendszus M., Nieswandt B., Stoll G. Targeting platelets in acute experimental stroke: impact of glycoprotein Ib, VI, and IIb/IIIa blockade on infarct size, functional outcome, and intracranial bleeding. Circulation. 2007;115:2323–2330. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.691279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clemetson J.M., Polgar J., Magnenat E., Wells T.N., Clemetson K.J. The platelet collagen receptor glycoprotein VI is a member of the immunoglobulin superfamily closely related to FcalphaR and the natural killer receptors. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:29019–29024. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.41.29019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ozaki Y., Suzuki-Inoue K., Inoue O. Novel interactions in platelet biology: CLEC-2/podoplanin and laminin/GPVI. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2009;7(Suppl 1):S191–S194. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2009.03372.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inoue O., Suzuki-Inoue K., McCarty O.J., Moroi M., Ruggeri Z.M., Kunicki T.J. Laminin stimulates spreading of platelets through integrin alpha6beta1-dependent activation of GPVI. Blood. 2006;107:1405–1412. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-06-2406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mammadova-Bach E., Ollivier V., Loyau S., Schaff M., Dumont B., Favier R. Platelet glycoprotein VI binds to polymerized fibrin and promotes thrombin generation. Blood. 2015;126:683–691. doi: 10.1182/blood-2015-02-629717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alshehri O.M., Hughes C.E., Montague S., Watson S.K., Frampton J., Bender M. Fibrin activates GPVI in human and mouse platelets. Blood. 2015;126:1601–1608. doi: 10.1182/blood-2015-04-641654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nieswandt B., Watson S.P. Platelet-collagen interaction: is GPVI the central receptor? Blood. 2003;102:449–461. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-12-3882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polgar J., Clemetson J.M., Kehrel B.E., Wiedemann M., Magnenat E.M., Wells T.N. Platelet activation and signal transduction by convulxin, a C-type lectin from Crotalus durissus terrificus (tropical rattlesnake) venom via the p62/GPVI collagen receptor. J. Biol. Chem. 1997;272:13576–13583. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.21.13576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrews R.K., Gardiner E.E., Asazuma N., Berlanga O., Tulasne D., Nieswandt B. A novel viper venom metalloproteinase, alborhagin, is an agonist at the platelet collagen receptor GPVI. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:28092–28097. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M011352200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wijeyewickrema L.C., Gardiner E.E., Moroi M., Berndt M.C., Andrews R.K. Snake venom metalloproteinases, crotarhagin and alborhagin, induce ectodomain shedding of the platelet collagen receptor, glycoprotein VI. Thromb. Haemost. 2007;98:1285–1290. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Tamimi M., Mu F.T., Arthur J.F., Shen Y., Moroi M., Berndt M.C. Anti-glycoprotein VI monoclonal antibodies directly aggregate platelets independently of FcgammaRIIa and induce GPVI ectodomain shedding. Platelets. 2009;20:75–82. doi: 10.1080/09537100802645029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrews R.K., Suzuki-Inoue K., Shen Y., Tulasne D., Watson S.P., Berndt M.C. Interaction of calmodulin with the cytoplasmic domain of platelet glycoprotein VI. Blood. 2002;99:4219–4221. doi: 10.1182/blood-2001-11-0008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Locke D., Liu C., Peng X., Chen H., Kahn M.L. Fc Rgamma-independent signaling by the platelet collagen receptor glycoprotein VI. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:15441–15448. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M212338200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmaier A.A., Zou Z., Kazlauskas A., Emert-Sedlak L., Fong K.P., Neeves K.B. Molecular priming of Lyn by GPVI enables an immune receptor to adopt a hemostatic role. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2009;106:21167–21172. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0906436106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stegner D., Haining E.J., Nieswandt B. Targeting glycoprotein VI and the immunoreceptor tyrosine-based activation motif signaling pathway. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2014;34:1615–1620. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.114.303408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson S.P., Herbert J.M., Pollitt A.Y. GPVI and CLEC-2 in hemostasis and vascular integrity. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2010;8:1456–1467. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2010.03875.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardiner E.E., Arthur J.F., Kahn M.L., Berndt M.C., Andrews R.K. Regulation of platelet membrane levels of glycoprotein VI by a platelet-derived metalloproteinase. Blood. 2004;104:3611–3617. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-04-1549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrews R.K., Gardiner E.E. Basic mechanisms of platelet receptor shedding. Platelets. 2016:1–6. doi: 10.1080/09537104.2016.1235690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardiner E.E., Andrews R.K. Platelet receptor expression and shedding: glycoprotein Ib-IX-V and glycoprotein VI. Transfus. Med. Rev. 2014;28:56–60. doi: 10.1016/j.tmrv.2014.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arthur J.F., Shen Y., Kahn M.L., Berndt M.C., Andrews R.K., Gardiner E.E. Ligand binding rapidly induces disulfide-dependent dimerization of glycoprotein VI on the platelet plasma membrane. J. Biol. Chem. 2007;282:30434–30441. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M701330200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arthur J.F., Gardiner E.E., Kenny D., Andrews R.K., Berndt M.C. Platelet receptor redox regulation. Platelets. 2008;19:1–8. doi: 10.1080/09537100701817224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arthur J.F., Gardiner E.E., Matzaris M., Taylor S.G., Wijeyewickrema L., Ozaki Y. Glycoprotein VI is associated with GPIb-IX-V on the membrane of resting and activated platelets. Thromb. Haemost. 2005;93:716–723. doi: 10.1160/TH04-09-0584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bakdash N., Williams M.S. Spatially distinct production of reactive oxygen species regulates platelet activation. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2008;45:158–166. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2008.03.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krotz F., Sohn H.Y., Gloe T., Zahler S., Riexinger T., Schiele T.M. NAD(P)H oxidase-dependent platelet superoxide anion release increases platelet recruitment. Blood. 2002;100:917–924. doi: 10.1182/blood.v100.3.917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pignatelli P., Pulcinelli F.M., Lenti L., Gazzaniga P.P., Violi F. Hydrogen peroxide is involved in collagen-induced platelet activation. Blood. 1998;91:484–490. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamagishi S.I., Edelstein D., Du X.L., Brownlee M. Hyperglycemia potentiates collagen-induced platelet activation through mitochondrial superoxide overproduction. Diabetes. 2001;50:1491–1494. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.50.6.1491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arthur J.F., Shen Y., Gardiner E.E., Coleman L., Murphy D., Kenny D. TNF receptor-associated factor 4 (TRAF4) is a novel binding partner of glycoprotein Ib and glycoprotein VI in human platelets. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2011;9:163–172. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2010.04091.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chari R., Kim S., Murugappan S., Sanjay A., Daniel J.L., Kunapuli S.P. Lyn, PKC-delta, SHIP-1 interactions regulate GPVI-mediated platelet-dense granule secretion. Blood. 2009;114:3056–3063. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-11-188516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bey E.A., Xu B., Bhattacharjee A., Oldfield C.M., Zhao X., Li Q. Protein kinase C delta is required for p47phox phosphorylation and translocation in activated human monocytes. J. Immunol. 2004;173:5730–5738. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.9.5730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chlopicki S., Olszanecki R., Janiszewski M., Laurindo F.R., Panz T., Miedzobrodzki J. Functional role of NADPH oxidase in activation of platelets. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2004;6:691–698. doi: 10.1089/1523086041361640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jang J.Y., Wang S.B., Min J.H., Chae Y.H., Baek J.Y., Yu D.Y. Peroxiredoxin II is an antioxidant enzyme that negatively regulates collagen-stimulated platelet function. J. Biol. Chem. 2015;290:11432–11442. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M115.644260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonomini F., Rodella L.F., Rezzani R. Metabolic syndrome, aging and involvement of oxidative stress. Aging Dis. 2015;6:109–120. doi: 10.14336/AD.2014.0305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Violi F., Pignatelli P. Platelet NOX, a novel target for anti-thrombotic treatment. Thromb. Haemost. 2014;111:817–823. doi: 10.1160/TH13-10-0818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Del Principe D., Menichelli A., De Matteis W., Di Giulio S., Giordani M., Savini I. Hydrogen peroxide is an intermediate in the platelet activation cascade triggered by collagen, but not by thrombin. Thromb. Res. 1991;62:365–375. doi: 10.1016/0049-3848(91)90010-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pignatelli P., Carnevale R., Di Santo S., Bartimoccia S., Sanguigni V., Lenti L. Inherited human gp91phox deficiency is associated with impaired isoprostane formation and platelet dysfunction. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2011;31:423–434. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.110.217885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drummond G.R., Selemidis S., Griendling K.K., Sobey C.G. Combating oxidative stress in vascular disease: NADPH oxidases as therapeutic targets. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2011;10:453–471. doi: 10.1038/nrd3403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nauseef W.M. Biological roles for the NOX family NADPH oxidases. J. Biol. Chem. 2008;283:16961–16965. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R700045200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leto T.L., Morand S., Hurt D., Ueyama T. Targeting and regulation of reactive oxygen species generation by Nox family NADPH oxidases. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2009;11:2607–2619. doi: 10.1089/ars.2009.2637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vara D., Campanella M., Pula G. The novel NOX inhibitor 2-acetylphenothiazine impairs collagen-dependent thrombus formation in a GPVI-dependent manner. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2013;168:212–224. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2012.02130.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delaney M.K., Kim K., Estevez B., Xu Z., Stojanovic-Terpo A., Shen B. Differential roles of the NADPH-oxidase 1 and 2 in platelet activation and thrombosis. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2016;36:846–854. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.116.307308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walsh T.G., Berndt M.C., Carrim N., Cowman J., Kenny D., Metharom P. The role of Nox1 and Nox2 in GPVI-dependent platelet activation and thrombus formation. Redox Biol. 2014;2:178–186. doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2013.12.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zorov D.B., Juhaszova M., Sollott S.J. Mitochondrial ROS-induced ROS release: an update and review. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2006;1757:509–517. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2006.04.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li W.G., Miller F.J., Jr., Zhang H.J., Spitz D.R., Oberley L.W., Weintraub N.L. H(2)O(2)-induced O(2) production by a non-phagocytic NAD(P)H oxidase causes oxidant injury. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:29251–29256. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M102124200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doughan A.K., Harrison D.G., Dikalov S.I. Molecular mechanisms of angiotensin II-mediated mitochondrial dysfunction: linking mitochondrial oxidative damage and vascular endothelial dysfunction. Circ. Res. 2008;102:488–496. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.107.162800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wosniak J., Jr., Santos C.X., Kowaltowski A.J., Laurindo F.R. Cross-talk between mitochondria and NADPH oxidase: effects of mild mitochondrial dysfunction on angiotensin II-mediated increase in Nox isoform expression and activity in vascular smooth muscle cells. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2009;11:1265–1278. doi: 10.1089/ars.2009.2392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroller-Schon S., Steven S., Kossmann S., Scholz A., Daub S., Oelze M. Molecular mechanisms of the crosstalk between mitochondria and NADPH oxidase through reactive oxygen species-studies in white blood cells and in animal models. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2014;20:247–266. doi: 10.1089/ars.2012.4953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daiber A. Redox signaling (cross-talk) from and to mitochondria involves mitochondrial pores and reactive oxygen species. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2010;1797:897–906. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2010.01.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulz E., Wenzel P., Munzel T., Daiber A. Mitochondrial redox signaling: interaction of mitochondrial reactive oxygen species with other sources of oxidative stress. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2014;20:308–324. doi: 10.1089/ars.2012.4609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daiber A., Di Lisa F., Oelze M., Kroller-Schon S., Steven S., Schulz E. Crosstalk of mitochondria with NADPH oxidase via reactive oxygen and nitrogen species signalling and its role for vascular function. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2017;174:1670–1689. doi: 10.1111/bph.13403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]