The Notch pathway is a conserved signaling network that regulates many cellular processes including renewal of stem cells, differentiation of multiple cell lineages, proliferation and apoptosis.1 Notch signaling involves the binding of Notch ligands to Notch receptors followed by proteolytic cleavage events, translocation of intracellular Notch (ICN) to the nucleus and regulation of target genes via the interaction of transcription factor CSL/RBPJ and the MAML family of transcriptional co-activators.1, 2 The Notch pathway is involved in lymphoid development and recurrent activating mutations in NOTCH1 contribute to T lymphoblastic leukemias.3 Whether Notch signaling is actively involved in the regulation of myeloid development and myeloid leukemogenesis is less clear due to conflicting reports.4, 5, 6 In this study, we abrogated canonical Notch signaling throughout the hematopoietic system to evaluate the role of Notch in myelopoiesis and to conclusively determine if inhibition of Notch signaling can contribute to aberrant myelopoiesis and lead to the development of a myeloid neoplasm.

To abrogate Notch signaling, we utilized the well-studied conditional DN-MAML1-GFP mouse model previously shown to block canonical Notch signaling via inhibition of Notch receptors 1–4.7 We disrupted Notch signaling throughout the hematopoietic system, including myeloid stem and progenitor cells, by intercrossing DN-MAML1-GFP mice with Vav-cre mice.8 The DN-MAML1-GFP is a fusion protein; thus evaluation of GFP levels by flow cytometry was used to track cells expressing DN-MAML1. As expected, doubly heterozygous mice demonstrated GFP expression in most of the cells in the bone marrow and to a lesser extent in the spleen and thymus (Figure 1a; Supplementary Figure 1). Some mice demonstrated a notable reduction of DN-MAML1 expressing cells only in the thymus, suggesting there is strong selective pressure in T cells to not express DN-MAML1.

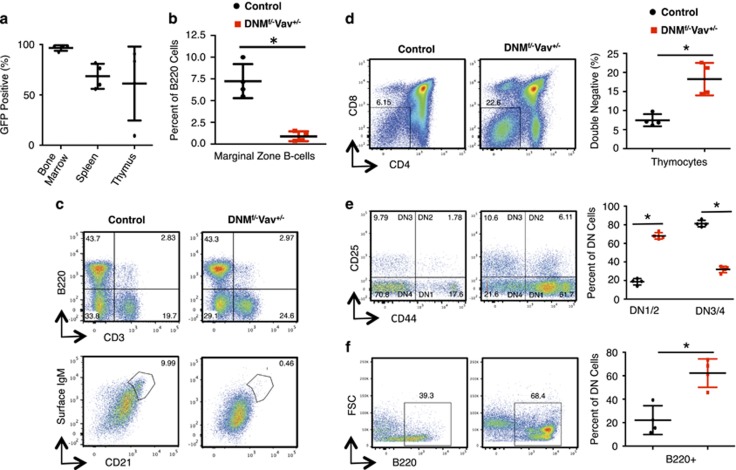

Figure 1.

DN-MAML1-GFP × Vav-cre (DNMf/−Vav+/−) mice have reduced marginal zone B-cells and increased immature T-cells. (a) DNMAML1 (GFP+) cells found in the bone marrow, spleen and thymus of DNMf/−Vav+/− mice were quantified using flow cytometry at 6 months (n=4). (b) MZ B-cells harvested from the spleens of control and DNMf/−Vav+/− mice were quantified using flow cytometry at 6 months (n=4). (c) Representative dot plots of MZ B-cells identified by gating on B220+CD3− cells (top panels), followed by sIgM+CD21+ cells (bottom panels). (d) Representative dot plots of double negative (DN) thymocytes isolated from DNMf/−Vav+/− and control mice at 6 months are identified as CD4−CD8− cells using flow cytometry. (e) Representative dot plots of DN subsets identified as CD4−CD8−CD25−CD44+ (DN1), CD4−CD8−CD25+CD44+ (DN2), CD4−CD8−CD25+CD44− (DN3) and CD4−CD8−CD25−CD44− (DN4) populations. (f) Additional analyses of DN cells using B-cell marker B220. Quantification of data from four mice for Figures 1d–f is shown in the right panels. Data are representative of two or more independent experiments. Statistical significance was determined by a two-tailed, unpaired t-test (*P⩽0.05).

To validate our mouse model, we first determined if canonical Notch signaling is decreased in mice doubly heterozygous for DN-MAML1-GFP and Vav-cre (DNMf/−Vav+/−). The development of marginal zone (MZ) B-cells in the spleen relies on Notch 2 signaling and Notch blockade results in the reduction of the MZ B-cell pool in murine spleens.7 As shown in Figures 1b and c, a significant reduction in the percentage of MZ B-cells was observed in DNMf/−Vav+/− mice compared to controls at 6 months. Second, we confirmed that these mice exhibited the expected abnormalities in thymocyte development, a Notch1 process.9 We found a significant increase in the double negative (DN) population within the GFP+ fraction of thymocytes taken from DNMf/−Vav+/− mice compared to controls (Figure 1d). Further evaluation of the DN thymocyte populations in DNMf/−Vav+/− mice showed a significant increase in the frequency of the more immature DN1/2 cells, a decrease in DN3/4 cells (Figure 1e) and an increase in B220+ B cells (Figure 1f). Taken together, these data provide confirmatory evidence that our in vivo model is sufficient to inhibit canonical Notch signaling over time.

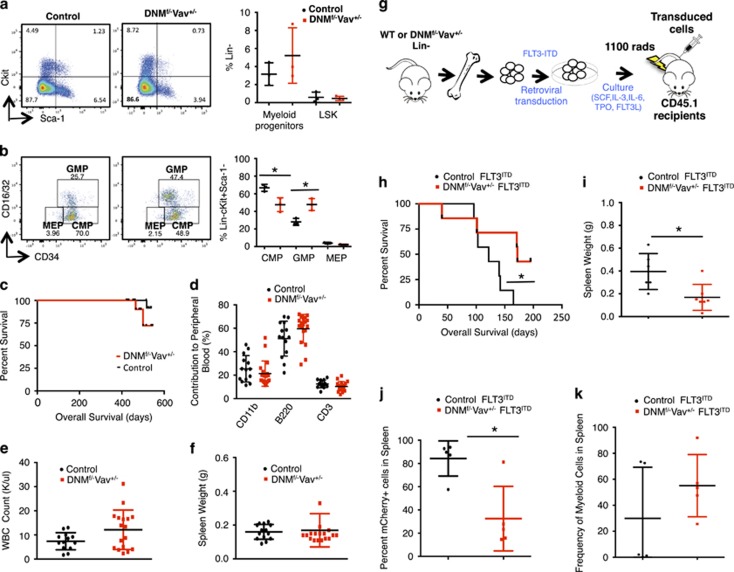

Earlier studies suggest that loss of Notch signaling can impair megakaryopoiesis leading to a decrease in megakaryocyte–erythroid progenitors (MEPs) at the expense of an increase in granulocyte–monocyte progenitors (GMPs).10 To determine whether loss of Notch signaling in our model affects the myeloid progenitor pool, we analyzed stem and progenitor compartments of control and DNMf/−Vav+/− mice at 6 months and 15–18 months. Analyses of DNMf/−Vav+/− mice at 15–18 months revealed a trend toward an increase in myeloid progenitors (Figure 2a), a significant increase in GMPs (Figure 2b) and a significant decrease in CMPs (Figure 2b). There was, however, no significant difference in the LSK (Figure 2a) or the CD150+CD48− LT-HSC populations (data not shown). A similar trend was observed in the spleens of these mice along with an increase in CD11b+ cells (Supplementary Figures 2A–E). This significant increase in GMPs was observed as early as 6 months (Supplementary Figure 3). Finally, bone marrow cells from mice expressing DN-MAML1-GFP produced fewer myeloid colonies in methylcellulose at 6 months (Supplementary Figure 4) compared to age-matched controls. The collective data suggest that loss of Notch signaling contributes to a decrease in CMPs and a mild but stable expansion of the GMP and myeloid compartments.

Figure 2.

Long-term inhibition of Notch signaling expands the GMP compartment but does not produce highly penetrant myeloid neoplasms. (a) HSPC analysis of bone marrow cells harvested from DNMf/−Vav+/− and control mice killed at 15–18 months. Representative dot plots showing DNMf/−Vav+/− LSK cells and total myeloid progenitors. DNMf/−Vav+/− HSPCs were identified by first gating on the GFP+ fraction of Lin-negative cells, followed by Sca-1+cKit+ cells (LSK) or Sca-1-cKit+ cells (total myeloid progenitors). (b) DNMf/−Vav+/− myeloid progenitor subsets were identified by gating on the GFP+ fraction of Lin-negative cells, followed by cKit+Sca-1- and CD16/32 versus CD34: CMP (Lin-Sca-1-cKit+CD16/32−CD34+), GMP (Lin-Sca-1-cKit+CD16/32+CD34+) and megakaryocyte–erythroid progenitors (MEP) (Lin-Sca-1-cKit+CD16/32−CD34−). Representative dot plots of HSPC analyses are shown in Figures 2a and b (left panels) and the quantification of data from three mice are graphed (right panels). (c) Kaplan–Meier plot of the survival of DNMf/−Vav+/− (n=19) and control (n=15) mice aged to 15–18 months. (d) Flow cytometric analysis of lineage subsets (Myeloid, B- and T-cells) in peripheral blood taken from DNMf/−Vav+/− (n=19) and control (n=14) mice at 18 months. (e) Complete blood counts were also performed using peripheral blood collected from mice at 18 months in order to compare the total number of WBCs in DNMf/−Vav+/− (n=17) and control (n=13) mice. (f) At 15–18 months, mice were killed, spleens were harvested and spleen weights were compared in the graph: DNMf/−Vav+/− (n=18); controls (n=14). (g) Donor BM cells were harvested from DNMf/−Vav+/− or control mice at killing, Lin- cells were transduced with FLT3ITD MSCV-Ires-mCherry (MIC) construct and transplanted into CD45.1 recipients. (h) Kaplan–Meier plot of the survival of DNMf/−Vav+/− FLT3ITD (n=7) and control-FLT3ITD (n=7) mice. (i) Spleen weights of DNMf/−Vav+/−FLT3ITD(n=7) and control-FLT3ITD (n=6) mice. (j) Frequency of FLT3ITD cells in the spleens of mice was determined by assessing mCherry levels using flow cytometry. (k) Immunophenotype of splenocytes from DNMf/−Vav+/−FLT3ITD (n=5) mice compared to control-FLT3ITD (n=5) was determined by staining samples with myeloid lineage markers (CD11b, Gr-1) and analyzing samples with flow cytometry. Statistical significance was determined by a two-tailed, unpaired t-test (*P⩽0.05).

Previous results from the disruption of Nicastrin showing marked expansion of myeloid cells prompted speculation that Notch functions as a tumor suppressor.5 To determine if canonical Notch signaling can function as a tumor suppressor in myelopoiesis, a tumor watch was established (n=19 DNMf/−Vav+/−; n=15 controls). The mice were aged to 15–18 months and there was no evidence of a highly penetrant myeloid disease with loss of canonical Notch signaling as shown by no significant difference in survival (Figure 2c), immunophenotype of the peripheral blood (Figure 2d) and white blood cell count between the two groups (Figure 2e). At the end point, the collective DN-MAML1 cohort also did not have splenomegaly (Figure 2f). During the course of the experiment, two mice died in the DNMf/−Vav+/− group near the end of the study; one had an enlarged spleen (0.510 g) but viable cells could not be obtained and the other died abruptly without splenomegaly. A single mouse in the control group also died abruptly without splenomegaly. These mice continued to show >90% GFP expression at 12 months and decreased MZ B-cells at 18 months (Supplementary Figures 5A–C), demonstrating that there was continued abrogation of Notch signaling. The above data suggest that although there is an expansion of GMPs and myeloid cells in mice that lack canonical Notch signaling, these changes are not sufficient to produce a myeloid neoplasm. It is possible that loss of Notch signaling in myeloid cells is insufficient for the development of myeloid neoplasms, but may cooperate with other events such as genes frequently mutated in AML.11 To test this hypothesis, we retrovirally expressed FLT3ITD (MSCV-Ires-mCherry) in control and DNMf/−Vav+/− lineage negative bone marrow cells followed by transplantation into syngeneic recipients (Figure 2g; Supplementary Figure 6A). By ~150 days, all control-FLT3ITD mice died, while there was an observed delay in disease progression and subsequent death of DNMf/−Vav+/− FLT3ITD mice (Figure 2h). There was a significant reduction in the spleen weights (Figure 2i) and frequency of mCherry+ cells in the spleen of DNMf/−Vav+/− FLT3ITD mice (Figure 2j). Immunophenotyping of splenocytes showed no significant differences within the myeloid lineage (Figure 2k). Further, in vitro methylcellulose experiments performed using Lin-marrow cells from both groups transduced with FLT3ITD mCherry construct showed no advantage in growth of DNMf/−Vav+/− FLT3ITD compared to control-FLT3ITDcells (Supplementary Figure 6B). Overall, these data suggest that loss of Notch signaling does not cooperate in vivo with FLT3ITD to induce a myeloid disease.

The results from our study demonstrate that prolonged loss of Notch signaling in vivo does not lead to a highly penetrant myeloid neoplasm. We found that expression of DN-MAML1-GFP in bone marrow cells, including hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells (HSPCs), resulted in a relative increase in GMPs that was stable over time and an increase in myeloid cells in the spleen. Despite these observations, there were no overt clinical features consistent with the development of a myeloid neoplasm. Our results are consistent with other studies that evaluated the impact of Notch inhibition on normal hematopoiesis via expression of DN-MAML1 or conditional ablation of the Rbpj gene.4 Additionally, our results regarding the impact of Notch blockade on leukemia growth using the FLT3ITD model is congruent with our previous data, which demonstrated that inhibition of Notch signaling, via retroviral expression of DN-MAML1 or treatment with gamma secretase inhibitors, can inhibit leukemia growth.6 Furthermore, inactivating mutations in the Notch pathway are uncommon in primary myeloid neoplasms.12 These studies are in contrast to the results from disruption of Nicastrin, which led to a marked expansion of myeloid cells and a fully penetrant myeloid neoplasm at 5 months, prompting speculation that Notch functions as a tumor suppressor in myeloid cells.5

These differences are likely multifactorial and include cell context, the varying contribution of intrinsic and extrinsic signaling and dosage of pathway modulation; altogether highlighting the complexity of the Notch pathway. To achieve loss of Notch1-4 signaling in vivo, we utilized the dominant-negative mastermind-like transgene in which the ICN transcriptional co-activator MAML1 is truncated and fused to GFP7 preventing the formation of the ternary complex that is required for the transcriptional activation of Notch target genes. This approach should yield a more specific disruption of canonical Notch signaling than deleting Nicastrin, which has other substrates besides Notch. Finally, we avoided the Mx-1 cre system, and relied on the more hematopoietic-specific Vav-cre model. Not only is the Mx-1-Cre transgene active in mesenchymal stem cells in the bone marrow stroma,13 but it requires an interferon response for induction and it’s well known that interferon signaling can alter stem cell function and induce proliferation of myeloid cells.14 Collectively, these features may lead to cell extrinsic effects on myeloid development and leukemogenesis.

Altogether, our results demonstrate that loss of Notch signaling in vivo is insufficient for the development of myeloid neoplasms. This lack of a strong phenotype observed after Notch blockade on normal hematopoiesis is encouraging for clinical studies evaluating the impact of different Notch pathway inhibitors on both solid and liquid tumors.15 Furthermore, our results highlight the importance of using selective in vivo mouse models of Notch perturbation for future evaluation of the underlying mechanisms of Notch signaling in myeloid malignancies.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by the American Lebanese Syrian Associated Charities of St Jude Children's Research Hospital and the NIH/NHLBI (KO8 HL116605 to JMK). JMK holds a Career Award for Medical Scientists from the Burroughs Welcome Fund. We thank Timothy Ley for critical reading of this manuscript. We also thank Mieke Hoock and Daniel George for providing invaluable animal husbandry and technical assistance. The DN-MAML1 conditional mice were a kind gift of Warren Pear and Ivan Maillard.

Footnotes

Supplementary Information accompanies this paper on Blood Cancer Journal website (http://www.nature.com/bcj)

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Andersson ER, Sandberg R, Lendahl U. Notch signaling: simplicity in design, versatility in function. Development 2011; 138: 3593–3612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu Y, Masiero M, Banham AH. Notch signaling: its roles and therapeutic potential in hematological malignancies. Oncotarget 2016; 7: 29804–29823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weng AP, Ferrando AA, Lee W, Morris JPt, Silverman LB, Sanchez-Irizarry C et al. Activating mutations of NOTCH1 in human T cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Science 2004; 306: 269–271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maillard I, Koch U, Dumortier A, Shestova O, Xu L, Sai H et al. Canonical notch signaling is dispensable for the maintenance of adult hematopoietic stem cells. Cell Stem Cell 2008; 2: 356–366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klinakis A, Lobry C, Abdel-Wahab O, Oh P, Haeno H, Buonamici S et al. A novel tumour-suppressor function for the Notch pathway in myeloid leukaemia. Nature 2011; 473: 230–233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grieselhuber NR, Klco JM, Verdoni AM, Lamprecht T, Sarkaria SM, Wartman LD et al. Notch signaling in acute promyelocytic leukemia. Leukemia 2013; 27: 1548–1557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maillard I, Weng AP, Carpenter AC, Rodriguez CG, Sai H, Xu L et al. Mastermind critically regulates Notch-mediated lymphoid cell fate decisions. Blood 2004; 104: 1696–1702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Georgiades P, Ogilvy S, Duval H, Licence DR, Charnock-Jones DS, Smith SK et al. VavCre transgenic mice: a tool for mutagenesis in hematopoietic and endothelial lineages. Genesis 2002; 34: 251–256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radtke F, Wilson A, Stark G, Bauer M, van Meerwijk J, MacDonald HR et al. Deficient T cell fate specification in mice with an induced inactivation of Notch1. Immunity 1999; 10: 547–558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mercher T, Cornejo MG, Sears C, Kindler T, Moore SA, Maillard I et al. Notch signaling specifies megakaryocyte development from hematopoietic stem cells. Cell Stem Cell 2008; 3: 314–326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levis M. FLT3 mutations in acute myeloid leukemia: what is the best approach in 2013? Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program 2013; 2013: 220–226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cancer Genome Atlas Research N. Genomic and epigenomic landscapes of adult de novo acute myeloid leukemia. N Engl J Med 2013; 368: 2059–2074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park D, Spencer JA, Koh BI, Kobayashi T, Fujisaki J, Clemens TL et al. Endogenous bone marrow MSCs are dynamic, fate-restricted participants in bone maintenance and regeneration. Cell Stem Cell 2012; 10: 259–272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Essers MA, Offner S, Blanco-Bose WE, Waibler Z, Kalinke U, Duchosal MA et al. IFNalpha activates dormant haematopoietic stem cells in vivo. Nature 2009; 458: 904–908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Purow B. Notch inhibition as a promising new approach to cancer therapy. Adv Exp Med Biol 2012; 727: 305–319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.