Abstract

There is a critical need for the discovery of novel biomarkers for early detection and targeted therapy of cancer, a major cause of deaths worldwide. In this respect, proteomic technologies, such as mass spectrometry (MS), enable the identification of pathologically significant proteins in various types of samples. MS is capable of high-throughput profiling of complex biological samples including blood, tissues, urine, milk, and cells. MS-assisted proteomics has contributed to the development of cancer biomarkers that may form the foundation for new clinical tests. It can also aid in elucidating the molecular mechanisms underlying cancer. In this review, we discuss MS principles and instrumentation as well as approaches in MS-based proteomics, which have been employed in the development of potential biomarkers. Furthermore, the challenges in validation of MS biomarkers for their use in clinical practice are also reviewed.

Keywords: mass spectrometry, proteomics, cancer biomarkers

Introduction

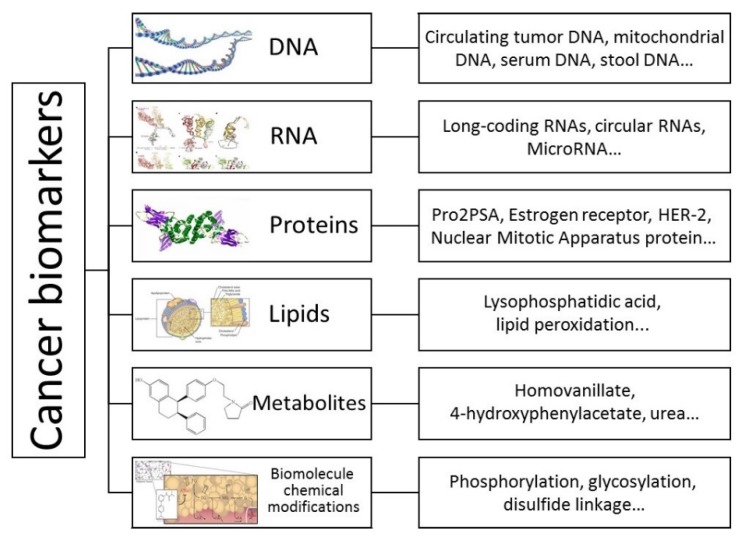

Cancer remains a major life-threatening disease with about 14.1 million new cases and 8.2 million cancer-associated mortalities reported in 2012 1. The global demographic and epidemiologic transitions signal an ever-increasing cancer burden over the next decades 2. Cancer is a multigene disease and each tumor is composed of a variety of cell populations with distinct morphologies and behaviors 3. Biomarkers such as proteins or biomolecular chemical modifications are quantifiable indicators of a specific biological state. In this respect, cancer-associated biomarkers are useful for studying disease, identifying patients at different clinical stages, and developing adaptive therapies 4. For example, recent studies have demonstrated that long noncoding RNAs, circular RNAs 5, circulating tumor DNAs 6, and non-essential amino acids that support numerous metabolic processes crucial for the growth and survival of proliferating cells 7 can serve as biomarkers for cancers. Also, epidermal growth factor receptor, which is associated with the development of certain types of cancers 8, is regarded as a useful tool for cancer detection (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Schematic illustration of biomarkers for various types of cancers. Biomarkers are quantitative indicators of a specific biological state; therefore, cancer-associated biomarkers are useful for understanding the molecular basis of disease, early detection, identifying patients at different clinical stages, and developing a personal therapy.

Cancer biomarkers can be classified into two categories including disease-related biomarkers and drug related biomarkers 9. A biomarker should be (i) a mediator of the disease pathology, (ii) present at low and stable expression levels in healthy individuals and higher expression levels in patients, and (iii) simple and quick to evaluate 10. Such a biomarker can be assayed and linked to cancer using a defined mechanism 11.

Recently, advanced molecular methods have been used in clinical diagnostic laboratories. Most novel techniques are based on transcriptional profiling and DNA methylation. However, compared with the genome and transcriptome, the proteome is more complex and dynamic 12. The term “proteome” was first used in 1994 to indicate all time- and condition-specific proteins that are simultaneously produced by a cell or a tissue 12. Proteins are often subject to proteolytic cleavage or post-translational modifications. Although genomics and transcriptomics can provide valuable information, they do not always reflect the variation of encoded proteins. Also, the association between mRNAs and protein expression levels is low compared with that of cell surface proteins 13. Since proteins are the functional molecules in an organism and may be most ubiquitously affected in disease, therapy response, and recovery, proteomics holds special promise in detecting pathological conditions, predicting the efficacy of treatment, and tailoring personalized medicine (Figure 2) 14.

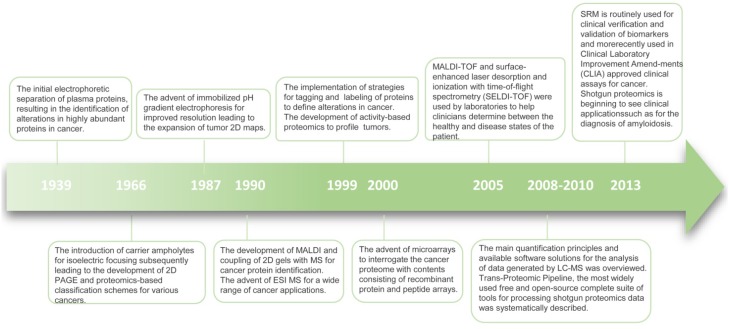

Figure 2.

Timeline of progress in proteomics.

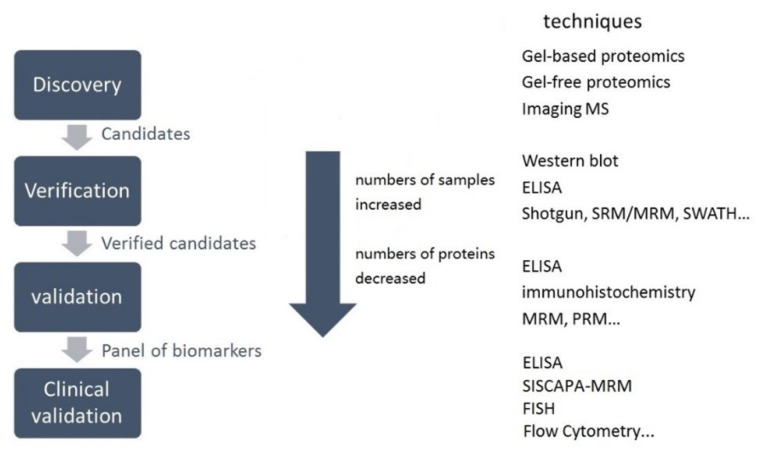

In a typical clinical proteomic study for diagnostic biomarker discovery, measurement of a large number of proteins in various samples is the first step. The initial protein candidates are proteins that are differentially expressed in patient and control samples 15. By confirmation of differential protein abundance in clinically useful samples, candidates can be progressively credentialed to yield a few specific proteins 15. Candidate biomarker verification should be included in the biomarker development pipeline (Figure 3) to provide reproducible and sensitive quantitative assays 16.

Figure 3.

Schematic representation of the various stages in the biomarker pipeline. SISCAPA is the acronym for Stable Isotope Standards and Capture by Antipeptide Antibodies. FISH is short for fluorescent in situ hybridization.

Because of the limited availability and accessibility of suitable reagents, most proteins in a species cannot be detected and quantified by affinity-based assays 17. Therefore, almost all currently available proteomic procedures and strategies use mass spectrometry (MS) techniques, which are capable of high-throughput profiling of complex samples. Nowadays, non-targeted MS methods have emerged as suitable tools to perform relative quantitation of a large number of proteins to discover novel protein biomarker candidates while targeted MS mode are applied to identify peptides of interest 18, 19. A variety of MS-based proteomic methods have been developed to identify and quantify proteins in biological and clinical samples 20-23 to obtain biomarker candidates. The present study describes various currently used MS-based proteomic approaches and their applications. Also, the challenges of biomarker validation for their use in clinical practice are discussed.

Principles and instrumentation

MS analysis utilizes electromagnetic fields in a vacuum, where the molecular mass of the charged particle is determined 3. MS is used to evaluate the molecular mass of a polypeptide or to determine additional structural features 17. Tandem MS/MS is performed in the latter case to determine detailed structural features of peptides. Moreover, MS-based proteomic methods can also be applied to characterize protein complexes 22. For example, protein conformation in solution and structural characterization of therapeutic proteins can be studied by hydrogen/deuterium exchange mass spectrometry (HDX-MS) 23.

MS instrumentation

In general, during MS analysis, the analyte is ionized in the gas phase, and the ions are subsequently separated according to their mass-to-charge ratio (m/z). Electrospray ionization (ESI) and matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization (MALDI) are two methods widely used to perform the protein ionization. Both techniques hold great potential for the characterization of biomolecules.

A mass analyzer is an instrument that determines the m/z of ions and the number of ions corresponding to a particular m/z is recorded by a detector. Quadrupole (QD), ion trap (IT), time-of-flight (TOF), orbitrap, and Fourier transform ion cyclotron resonance (FTICR) are common types of mass analyzers. Numerous mass analyzers are often combined to achieve maximum performance 24. For example, Muntel et al. used a quadrupole orbitrap instrument for urine protein biomarker discovery 25. Moreover, the workflow of a MALDI imaging mass spectrometer (MALDI IMS) enables the histology-directed analysis of the mass spectra using tissues 26, 27. In addition, optical density mass analyzers, known for their tolerance of high pressure, are particularly suited to the pulsed nature of ESI.

MS methodologies

Two-dimensional electrophoresis (2-DE) and chromatography-based proteomics

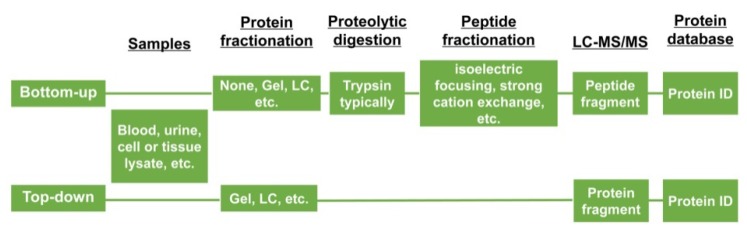

There are two main approaches to identify proteins applying gel-based proteomics, including bottom-up and top-down proteomics. In the former approach, proteins separated by two-dimensional polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (2D-PAGE) or in some instances, such as shot-gun proteomics wherein the fractionation step is left out, are digested in gel and then analyzed by MS 28, 29. Which means the proteins are digested using chemicals or enzymes before introducing them into MS. Needless to say, this strategy may have several problems including the occurrence of modifications on disparate peptides. while the top-down approach, on the other hand, both the intact proteins and fragment ions masses can be measured 30 (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Two categories of proteomic experiments.

2-DE has been applied in proteomic research since its introduction in 1975. For example, Klein et al. used the 2DE-MS approach to analyze the nuclear proteome of human gastric cancer cell lines with and without inactivation of hypoxia-inducible factor 1 31, 32. The shortcomings of this strategy include a limited dynamic range and low-throughput analysis 3. Although 2-D gel is still a powerful technique in proteomic analyses 33, 34, such as alternative detection for modification of specific proteins 35, attempts have been made to alleviate these drawbacks by using other techniques such as three-dimensional gel electrophoresis 36.

Shotgun based proteomics

Shotgun proteomics, also referred to as discovery proteomics, is a successfully used method 37. It is based on employing a liquid chromatography-tandem MS (LC-MS/MS) for data-dependent acquisition (DDA) or in some certain occasions data-independent acquisition (DIA) mode. In DDA mode, peptide fragmentation is guided by the abundance of peptide ions detected in a survey scan. The recorded information of specific ions is searched against a protein database to determine the peptide sequence and protein identity 38. In addition to its exquisite specificity, DDA-based proteomics has numerous other advantages, including unbiased and free-from hypotheses 39. DIA offers advantages over conventional DDA methods as it overcomes the stochastic, intensity-based selection of peptide precursors 40.

One of the applications of the shotgun approach is to generate spectral libraries for mass spectrometric reference maps 41, 42. It has also been used for the analysis of unique types of samples with biological and clinical importance including serum 43 and plasma 44, 45. In a previous study, shotgun proteomics was applied to detect changes in protein profiles related to lung cancer 46.

Although many MS-based proteomic studies were performed using shotgun proteomics, the stochastic sampling of this technique markedly affects reproducible detection 47. Furthermore, in traditional shotgun proteomics experiments, a large number of MS/MS spectra are collected. Peptide sequences are assigned using database searching algorithms, such as Sequest and PepExplorer, which use rigorous pattern recognition to assemble a list of homologous proteins 48. However, not all spectra acquired are matched to peptides. To investigate this problem, Chick et al. identified unassigned peptides and demonstrated that at least one-third of unmatched spectra arise from peptides with substoichiometric modifications 49.

SRM-based proteomics

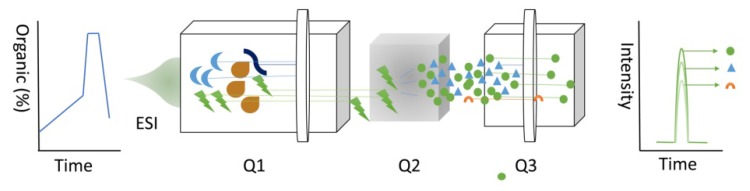

The adaptation of targeted data acquisition in the form of selected reaction monitoring (SRM), approximately a decade ago, was initially motivated by the requirement for robust and sensitive quantification of proteins 50. Numerous LC-MS workflows employ shotgun LC-MS; however, many others require a significantly higher reproducibility, sensitivity, accuracy, and precision of SRM 51. SRM, also known as multiple reaction monitoring, uses triple Quadrupole (QD) (Figure 5), where molecular ions are selected in Q1, collision-activated dissociation fragmentation is performed in Q2, and unique fragments ions are evaluated in Q3 52. SRM is an attractive choice for sample analysis due to its sensitivity 53.

Figure 5.

SRM technique.

Advances in SRM have led to the discovery of numerous allergens in food complexes and cancer-related proteins 54, 55, 56. Recently, by adding an isotopically labeled protein (15N-α-S1-casein), accuracy of SRM analysis was increased 57. In addition, absolute quantitation (AQUA), which has benefits of linearity over four orders of magnitude 58 and inter-laboratory comparability, also demands its use in allergen quantitation 59.

SRM has also been applied in biological fields 60, metabolic processes 61, signaling pathways 62, and validation of potentially interesting proteins 63. As protein-protein interaction networks are significantly important in biological processes, it is essential to develop a computational method to predict protein-protein interactions. For example, Huang et al. proposed an efficient strategy that used a weighted sparse representation-based classifier model and novel feature extraction to sequence proteins for construction of protein-protein networks. 64. Since investigation of phosphorylation events may serve an important role in biological research, Angeleri et al. developed an efficient strategy to obtain information regarding the phosphorylated sites 65.

Targeted data acquisition by SRM has been successful; however, the technique has intrinsic limitations. For example, the sensitivity of SRM currently cannot achieve the entire space of all organisms. Furthermore, the isolation width of Q1 can lead to false positive identifications 66. Recent improvements, including time-scheduled SRM or intelligent SRM, have increased the scale and improved the quality of SRM evaluations 67. In addition, parallel reaction monitoring has been developed markedly in instrumentation and software 68, 69.

Sequential window acquisition of all theoretical mass spectra (SWATH)-based proteomics

SWATH, a recently developed methodology 70, 71, 72 that relies on peptide spectral libraries, can be established by shotgun or obtained from community data repositories. Therefore, in contrast to SRM, SWATH-MS can quantify unlimited number of peptides that are included in spectral libraries.

SWATH-MS can be used in quantitative interaction proteomics 73, 74, 75. For example, Ortea et al. provided evidence that LC-MS/MS combined pre-treatment and SWATH-MS was effective to identify lung cancer biomarker candidates 76. SWATH-MS is also useful for the identification of candidate biomarkers, which will be further discussed in the following section 77, 78.

Additionally, there have been attempts to optimize the SWATH-MS workflow. The generation of a reference assay library is one of the key challenges and limitations of this approach 79. It has been demonstrated that combined assay libraries can be used for SWATH data extraction 78, and certain software tools have been proposed for creating combined assay libraries 80, 81. The parameters of MS detection were also optimized to increase the size of the library and decrease systematic errors 82. These developments have broadened the application of SWATH.

Multiplexed MS/MS

In SWATH and other DIA approaches, peptides and their modified forms are difficult to distinguish because of the width of the window used for the isolated precursor. Egertson et al. introduced and improved the DIA framework, multiplexed MS/MS, to overcome the constraint on the scanning speed of the instrument 83. The authors also suggested that this method may exploit other strengths of DIA 84.

Multiplexed MS/MS has certain disadvantages. It is more suitable for complex samples rather than simple mixtures due to its likely effect on the detection of low abundance peptides. Furthermore, the de-multiplexing and reconstruction of multiplexed MS/MS data may be a time-consuming process 85.

Application of MS in cancer biomarker discovery

Gastric, pancreatic, and liver cancers

Gastric cancer has one of the highest mortality rates worldwide 86, 87 urgently requiring its early detection 88, 89. Studies of gastric cancer biomarkers mainly focus on tissues 90, blood 91, and biological fluids to identify protein, RNA 92, and DNA 93. MS-based proteomics can aid in the identification of protein biomarkers and help study the mechanisms underlying gastric cancer 94. Using MALDI-TOF-MS, Yang et al. analyzed serum samples obtained from 70 patients with gastric cancer and 72 healthy volunteers and identified two peptides (P < 0.001) related to gastric cancer 95. Quantitative MS-based proteomic approaches include SCI techniques or label-free strategies in gastric cancer research. A variety of sources have been used to identify gastric cancer biomarkers, such as serum, gastric fluid 96, 97, cells obtained from tumor sections 98, cancer stem cells, circulating tumor cells 99, plasma membrane 100, saliva, plasma 101 and cancer tissues 102.

Cancer stem cells (CSCs) have been suggested to be extremely resistant to chemotherapy 103, 104. Therefore, the identification of CSC markers has become a novel therapeutic perspective. Yashiro et al. used CSC-like side population cells to identify novel biomarkers of gastric CSCs 105.

Pancreatic cancer has been described as one of the most lethal tumors 106 with 45220 new cases and 38460 mortalities reported in the US in 2013 107, 108. There is a critical need for developing clinically useful biomarkers for pancreatic cancer detection. Carcinoma antigen 19-9 (CA19-9) is a biomarker which has been shown to be significant in the diagnosis, prognosis, and management of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma 109. However, CA19-9 reacts with the sialylated Lewisa blood group antigen present in the glycoprotein serum fraction 110. 5-10% of the general population has the Lewisa-b- phenotype; therefore, CA19-9 is not an appropriate biomarker for these individuals 111. To overcome this problem, Yoneyama et al. identified insulin-like growth factor-binding protein 2 (IGFBP2) (AUC value of 0.706) and IGFBP3 (AUC value of 0.766) as plasma biomarkers for early detection of invasive ductal adenocarcinoma of pancreas 112. In another biomarker study, Zhong et al. described a 2D-MALDI-TOF-TOF-MS/MS combined strategy for isolating and identifying membrane proteins. Immunohistochemical staining experiment demonstrated that the biomarker candidate they discovered was downregulated in pancreatic cancer tissue (P < 0.05) 113. In another example, Tatsuyuki et al. identified novel prognostic markers by applying MS-based proteomic analysis 114.

HCC is the most common primary liver malignant disease 115. HCC-associated mortality is high due to numerous contributing factors 116. Therefore, there is an urgent need to develop clinical biomarkers that enable early detection for HCC 117. Megger et al. performed 2-DE and label-free ion intensity-based quantification by applying MS and LC to identify differential protein abundance in HCC and control tissues 118. Later, the same group combined previous results with label-free analysis 119. In another study, Wang et al. analyzed five HCC subline variants using 2-DE coupled with MALDI-TOF MS 120.

Colorectal cancer (CRC)

CRC is the third most common cancer diagnosed and one of leading causes of cancer-related deaths in the US and 121. The survival of patients with CRC is primarily associated with the stage of cancer 122. However, limited number of CRC biomarkers have been developed 123. Prognostic biomarkers could help the management of CRC 124. Tomonaga et al. used the isobaric tags for relative and absolute quantitation (iTRAQ) shotgun method to discover biomarker candidates, which were subsequently validated by SRM 125. Bosch et al. identified potential cancer markers to improve the diagnostic accuracy of the fecal immunochemical test to detect small traces of the blood protein, hemoglobin 126. In another study investigating CRC, Peltier et al. combined iTRAQ technology 128, 129, 130 with reversed-phase liquid chromatography and MALDI-TOF/TOF to perform quantitative proteomic analysis of adenoma, CRC, and healthy control serum samples 127.

Glycosylation is important in many biological processes, such as immune surveillance for tumors 131, 132, 133. Protein glycosylation commonly occur with the addition of specific glycan residues to asparagine (N-linked glycosylation) 134. Sethi et al. utilized LC-MS/MS-based N-glycoproteomics to map the N-glycome landscape associated with a panel of colorectal cell lines and described a novel method to identify disease-associated markers 135. In another study investigating CRC, a fluorogenic derivatization-LC-MS/MS approach was utilized to perform a differential proteomic analysis of normal and cancer cells 136.

Lung cancer

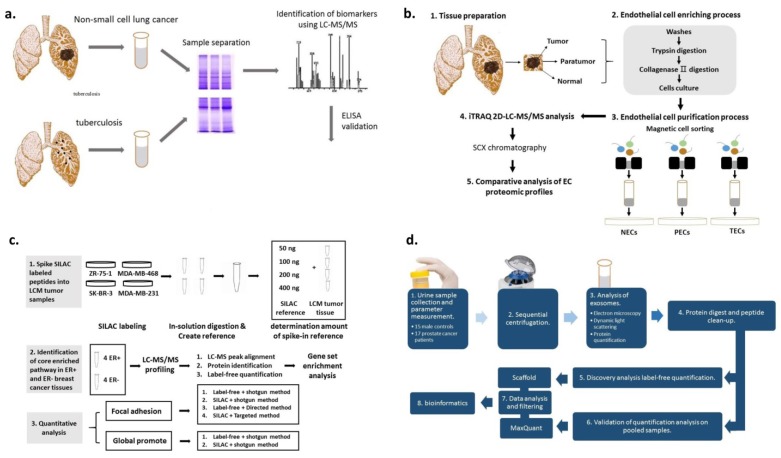

Lung cancer can be classified into small cell (SCLC) and non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) 137, 138. Numerous previous studies have demonstrated that pleural effusions contain proteins of potential diagnostic value 139, 140. Recently, the proteome of pleural effusion in patients with NSCLC was investigated using pleural fluid from 20 patients with NSCLC and 10 patients with tuberculosis (Figure 6a) 141.The homodimeric glycoprotein stanniocalcin 2 was reported to serve numerous roles in a variety of cancer subtypes. By applying MS/MS analysis on tissue samples from 53 cancer patients, Na et al. revealed that stanniocalcin 2 was upregulated in lung cancer cells 142.

Figure 6.

(A) Schematic illustration of proteome screening of pleural effusions to identify biomarkers for NSCLC. 1D SDS-PAGE was performed to separate proteins in pleural fluids. ELISA was used for the validation of protein candidates. (B) Schematic diagram of the experimental design. Normal, para-tumor-, and tumor-derived cluster of differentiation (CD) 105+ endothelial cells (ECs) were isolated, followed by iTRAQ-2DLC-MS/MS-based protein abundance profiling and comparative analysis of profiles. (C) Schematic diagram of the experimental design of systematic comparison between various quantitative methods for quantification of proteins within one pathway. (D) Schematic diagram of the experimental design for the isolation and characterization of urinary exosomes.

MALDI-TOF-MS has been used in numerous cancer studies 143. It has been shown that endothelial cells (ECs) play an important role in the tumor microenvironment 144, 145 and the properties of tumor-derived ECs are different from normal ECs 146. Zhuo et al. isolated ECs from lung squamous cell carcinoma using magnetic beads (Figure 6b) 147. Using the same method, Jin et al. discovered a protein candidate which was related to the histological presence of lymph node metastasis and neural invasion (p < 0.01) 148.

Toxicity and drug resistance remain major challenges facing cancer therapy. Efforts have been made to discover ideal biomarkers to improve the treatment efficiency. Rovithi et al. developed a serum peptide algorithm to classify cancer patients with regard to their clinical outcome 149. To guide the radiotherapeutic method and avoid severe toxicity, Walker et al. investigated the alterations in blood during therapy 150.

The collection of saliva is less invasive compared with collection of the blood 151 or tissue making it an attractive biological fluid for diagnosis. Xiao et al. used 2D-MS to analyze two pooled samples. The results indicated that saliva analyses might be established for lung cancer detection 152.

Advances in MS help in mapping a large number of mass spectrophotometric peaks to reference libraries 153. Using LC-SRM, 17 circulating proteins could be identified as potential cancer biomarkers in plasma samples collected from 72 patients 154. However, despite extensive efforts in lung cancer diagnosis, it remains challenging to move protein candidates in the clinic 155-158.

Melanoma

Melanoma is a skin cancer with a high mortality rate 159. Besides serum, urine, and cell lines, proteomics can also be used for quantitative analysis on formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tissues. For example, Byrum et al. used label-free quantitative MS to analyze FFPE to identify potential targets for the therapy of melanoma 160. Qendro et al. performed LC-MS/MS to profile five melanoma cell lines, a tissue sample of metastatic melanoma, and a benign melanocyte cell strain 161. Bioinformatics analysis was performed with each group of proteins to assign over-represented Gene Ontology terms.

Extracellular vesicles including exosomes are one of the mechanisms used for cell-cell communication. Exosomes are initially defined as reticulocyte-secreted vesicles secreted by many cell types 161, 162. Exosomes play an important role in cancer progression 163. Previous studies demonstrated that melanoma exosomes may influence disease progression by enhancing immunosuppression 164, angiogenesis, and tumor metastasis 165, 166. Lazar et al. performed proteomic analysis of seven melanoma cell lines and demonstrated that exosomes may be a potential biomarker for melanoma classification 167.

Uveal melanoma (UM) is a primary malignancy of eye the etiology of UM remains poorly understood. According to clinical, histopathological, and genetic features of these tumors, patients with UM can be classified into low-risk and high-risk metastatic groups 168. Crabb et al. performed global quantitative proteomic analysis of UM to increase our understanding of UM metastasis processes and to identify biomarkers of UM metastasis 169. MS-based proteomics using the untargeted MS method to discover novel protein biomarker candidates and the targeted MS mode to identify peptides of interest, has been a useful tool in melanoma research 170.

Breast cancer

Breast cancer contributes to approximately 14% of the cancer-associated mortality 171. Although 5-year survival rates have improved, ≥20% of all patients continue to develop metastatic disease with an associated poor outlook 172. Hormone receptor positive, erb-b2 receptor tyrosine kinase 2 (ErbB2) positive, and hormone (estrogen or progesterone) receptor and ErbB2 negative breast cancers are the four main types of this aggressive disease 173.

Breast milk is an appropriate cancer microenvironment for identifying breast cancer biomarkers. Aslebagh et al. used a nanoLC-MS/MS to analyze breast milk samples collected from patients with cancer and controls. The results demonstrated that sample-specific bands were present between the two groups 174. Besides milk, serum is also used for identifying breast cancer-specific markers 175-182. Dowling et al. combined metabolomics and proteomics platforms to analyze cancer and non-cancer serum samples 175. High mobility group protein HMG-I/HMG-Y (HMGA1) abundance level was found to be associated with breast cancer clinicopathological features. Maurizio et al. utilized label-free shotgun MS to analyze the proteins extracted from HMGA1-silenced cells and control breast cancer cell line MDA-MB-231 176. Ning Qing Liu et al. evaluated numerous approaches for global proteome quantification and proteins involved in a signaling pathway in breast cancer tissues were identified (Figure 6c) 177. Yang et al. collected serum samples from 183 breast cancer patients and 64 healthy controls to extract peptides using magnetic beads and analyzed by them MALDI-TOF-MS 178. Besides serum, urine was also used in proteomic studies to analyze its feasibility as a potential source for breast cancer biomarkers 183.

Ovarian and uterine cervical cancers

Ovarian cancer consists of numerous distinct subtypes 184, 185. However, the gold-standard biomarker, CA125, only performs well in one of these. A number of novel protein biomarkers relevant to ovarian cancer have been identified using MS-based proteomics 186. Nepomuceno et al. applied LC-MS/MS on tissues obtained from chickens that developed ovarian tumors spontaneously as an emerging experimental model to investigate the ovarian cancer proteome and reported the upregulation of an inhibitor in tumors (p = 0.0005) 187. Also, Poersch et al. performed LC-MS/MS on tumor fluids to identify ovarian cancer-associated protein biomarkers 188.

Drug resistance is a major challenge for ovarian cancer chemotherapeutic treatments. Therefore, it is essential to discover biomarkers that can distinguish chemosensitive and chemoresistant ovarian cancer patients 189. Based on the LC-MS/MS results acquired from epithelial ovarian cancer, Chappell et al. hypothesized that mitochondrial proteome changes were required to develop chemotherapy drug cisplatin resistance 190. In another study, Zhang et al. analyzed the protein abundance level in chemotherapy drug paclitaxel-resistant ovarian cancer cells and tissues 191.

Using iTRAQ and LC-MS platform, Shetty et al. revealed that major histocompatibility complex class 1 (p < 0.01) may be related to ovarian cancer drug resistance 192. In addition, the mechanism underlying somatic genome effects on the cancer proteome and associations between post-translational modification levels of proteins and clinical outcomes in high-grade serous carcinomas have been investigated 193.

Since Papanicolaou (Pap) test was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 1996, a vast majority of cervical cancer screening has used liquid-based Pap test 194, 195. Boylan et al. examined the proteins present in residual Pap test fixative samples from females with normal cervical cytology by 2-D-MS/MS and created a “Normal Pap test Core Proteome” 196. More recently, the same group used iTRAQ to quantify the proteins in Pap test samples from patients with ovarian cancer compared with healthy controls or patients with benign gynecological disease 197. The labeled samples were analyzed by 2D-LC-MS/MS. The results demonstrated that Pap test samples may be a valuable source for the identification of ovarian cancer biomarkers 197.

Urinary cancers

Urinary cancers include kidney, bladder, prostate, and testicular cancers 198. Sensitive and accurate MS quantitative analyses have been introduced for biomarker discovery in these cancers 199. Zhao et al. performed quantitative proteomic analysis on clear cell renal cell carcinoma (RCC) and adjacent kidney tissues using LC-MS/MS 200. Urine is a rich resource for the investigation of kidney physiology as well as diagnosis of glomerulonephritis, hypertensive nephropathy, and renal cancer 201. Sandim et al. investigated the proteins in urine samples collected from 64 patients with clear cell RCC and compared them with the healthy controls 202, whereas Neely et al. combined proteo-transcriptomic analysis and investigated alterations in protein abundance 203.

Prostate cancer is among the most common types of adult malignancies with an estimated 220,000 American males diagnosed with the disease annually 204. Sensitive biomarkers would improve the efficiency of diagnosis, prognosis, and personalized therapy of prostate cancer. Øverbye et al. identified proteins with differential abundance in 16 prostate cancer patients compared to 15 healthy controls by MS-based proteomics (Figure 6d) 205. Kim et al. developed SRM-MS assays in post-digital rectal examination urine samples. The results demonstrated that this strategy may accurately identify non-invasive biomarkers 206.

Urine is also considered to be an attractive source for bladder cancer biomarkers identification 204, 208. Guo et al. proposed a strategy to identify urine proteins associated with bladder cancer 209. In Europe and North America, a majority of bladder cancers are urothelial carcinomas 210. Lin et al. used MALDI-TOF spectrometry on urinary exosomes for the determination of urothelial biomarkers 211.

MS-based proteomics has also been used to identify testicular cancer biomarkers. Liu et al. used the proteomics platform to identify proteins that participate in spermatogenesis and can, therefore, serve as novel targets for the treatment of male infertility and cancer 212. The proteins they identified may also be used for personalized therapy for patients with testicular cancer.

Challenges in biomarker implementation and future prospects

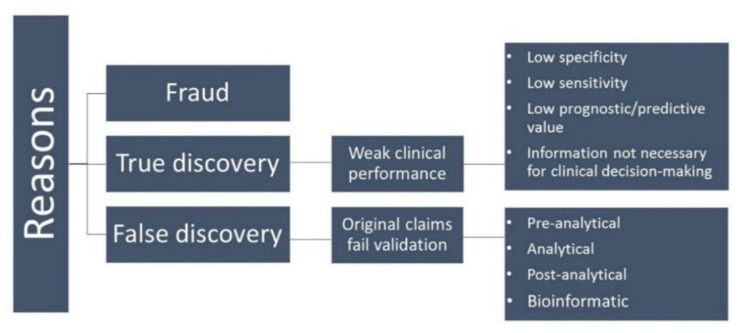

Cancer progression is a comprehensive event that makes biomarker development a challenging task. Despite rapid advances in academia and industry, not many biomarkers move on to clinical practice 213. Failure of cancer biomarkers appears to be due to several distinct challenges depicted in Figure 7 214.

Figure 7.

Schematic illustration of potential reasons for failure of biomarkers in clinical practice.

The first category of fraud is quite rare 215. False discovery is a major reason for failure of biomarkers to reach the clinic. These biomarkers fail at independent reproduction in the validation phase 216, 217. Small sample size as well as control samples used in the experiments that are not matched for age, sex, and race can lead to deceptive results 218. Other important issues to be considered include, criteria for selection and inclusion of samples, strict standards for collecting and handling samples, suitability of the methodology, for the analysis of the data obtained, and, most importantly, independent validation of the identified biomarkers 219, 220.

Although few cancer biomarkers have entered clinical use, there are numerous ways to improve the situation. For biomarkers with low specificity and sensitivity that are not suitable for clinical use, it is possible to combine a panel of different biomarkers to identify clinical scenarios 214. For example, a novel ovarian cancer biomarker, human epididymis protein 4, is not superior to CA125, which is an FDA-approved marker for ovarian cancer 221. However, by combining human epididymis protein 4 and CA125, diagnosis of malignant versus benign pelvic masses can be improved 222. For false discovery or artefactual biomarkers, understanding of the biological and molecular heterogeneity of disease states is required to guide the experimental design 223. In addition, efforts should be taken made for improving the MS technologies to explore proteins with lower abundance 224.

Conclusion

Because of recent advances in MS-based proteomics together with streamlined sample preparation, improved instrumentation, and combination of various analytical platforms, numerous cancer biomarkers have been identified with diagnostic and prognostic values. The challenge is to realize the diagnostic and prognostic potential of these biomarkers in the clinical practice.

Acknowledgments

This research was financially supported by NSFC (61527806, 61401217 and 61471168), Chinese 863 Project (2015AA020502), the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2017YFA0205300), Open Funding of State Key Laboratory of Oral Diseases (SKLOD2017OF04) China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (2016T90403), and the Economical Forest Cultivation and Utilization of 2011 Collaborative Innovation Center in Hunan Province [(2013) 448].

References

- 1.Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Dikshit R, Eser S, Mathers C, Rebelo M. et al. Cancer incidence and mortality worldwide: sources, methods and major patterns in GLOBOCAN 2012. Int J Cancer. 2015;136:E359–E86. doi: 10.1002/ijc.29210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stewart B, Wild CP. World cancer report 2014. World; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mäbert K, Cojoc M, Peitzsch C, Kurth I, Souchelnytskyi S, Dubrovska A. Cancer biomarker discovery: current status and future perspectives. Int J Radiat Biol. 2014;90:659–77. doi: 10.3109/09553002.2014.892229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jin C, Qiu L, Li J, Fu T, Zhang X, Tan W. Cancer biomarker discovery using DNA aptamers. Analyst. 2016;141:461–6. doi: 10.1039/c5an01918d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Li P, Chen S, Chen H, Mo X, Li T, Shao Y. et al. Using circular RNA as a novel type of biomarker in the screening of gastric cancer. Clin Chim Acta. 2015;444:132–6. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2015.02.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tabernero J, Lenz H-J, Siena S, Sobrero A, Falcone A, Ychou M. et al. Analysis of circulating DNA and protein biomarkers to predict the clinical activity of regorafenib and assess prognosis in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer: a retrospective, exploratory analysis of the CORRECT trial. Lancet Oncol. 2015;16:937–48. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(15)00138-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yang M, Vousden KH. Serine and one-carbon metabolism in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2016;16:650–62. doi: 10.1038/nrc.2016.81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ilkhani H, Sarparast M, Noori A, Zahra Bathaie S, Mousavi MF. Electrochemical aptamer/antibody based sandwich immunosensor for the detection of EGFR, a cancer biomarker, using gold nanoparticles as a signaling probe. Biosens Bioelectron. 2015;74:491–7. doi: 10.1016/j.bios.2015.06.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Goossens N, Nakagawa S, Sun X, Hoshida Y. Cancer biomarker discovery and validation. Transl Cancer Res. 2015;4:256. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2218-676X.2015.06.04. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Batrla R, Jordan BW. Personalized health care beyond oncology: new indications for immunoassay-based companion diagnostics. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2015;1346:71–80. doi: 10.1111/nyas.12754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shin J KG, Lee J W. et al. Identification of ganglioside GM2 activator playing a role in cancer cell migration through proteomic analysis of breast cancer secretomes. Cancer Sci. 2016;107:828–35. doi: 10.1111/cas.12935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hudler P, Kocevar N, Komel R. Proteomic approaches in biomarker discovery: new perspectives in cancer diagnostics. The Scientific World J. 2014; 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bausch-Fluck D, Hofmann A, Bock T, Frei AP, Cerciello F, Jacobs A. et al. A mass spectrometric-derived cell surface protein atlas. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0121314. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0121314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hanash S, Taguchi A. The grand challenge to decipher the cancer proteome. Nat Rev Cancer. 2010;10:652–60. doi: 10.1038/nrc2918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Skates SJ, Gillette MA, LaBaer J, Carr SA, Anderson L, Liebler DC. et al. Statistical Design for Biospecimen Cohort Size in Proteomics-based Biomarker Discovery and Verification Studies. J Proteome Res. 2013;12:5383–94. doi: 10.1021/pr400132j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Boja E, Rivers R, Kinsinger C, Mesri M, Hiltke T, Rahbar A. et al. Restructuring proteomics through verification. Biomark Med. 2010;4:799–803. doi: 10.2217/bmm.10.92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Domon B, Aebersold R. Options and considerations when selecting a quantitative proteomics strategy. Nat Biotechnol. 2010;28:710–21. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Andrew G Chambers AJP, Romain Simon & Christoph H Borchers. MRM for the verification of cancer biomarker proteins: recent applications to human plasma and serum. Expert Rev Proteomic. 2014;11:137–48. doi: 10.1586/14789450.2014.877346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jedrychowski Mark P, Wrann Christiane D, Paulo Joao A, Gerber Kaitlyn K, Szpyt J, Robinson Matthew M. et al. Detection and Quantitation of Circulating Human Irisin by Tandem Mass Spectrometry. Cell Metab. 2015;22:734–40. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2015.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Parker CE, Borchers CH. Mass spectrometry based biomarker discovery, verification, and validation — Quality assurance and control of protein biomarker assays. Mol Oncol. 2014;8:840–58. doi: 10.1016/j.molonc.2014.03.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Popescu ID, Codrici E, Albulescu L, Mihai S, Enciu A-M, Albulescu R. et al. Potential serum biomarkers for glioblastoma diagnostic assessed by proteomic approaches. Proteome Sci. 2014;12:47. doi: 10.1186/s12953-014-0047-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tran BQ, Goodlett DR, Goo YA. Advances in protein complex analysis by chemical cross-linking coupled with mass spectrometry (CXMS) and bioinformatics. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2016;1864:123–9. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2015.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wei H, Mo J, Tao L, Russell RJ, Tymiak AA, Chen G. et al. Hydrogen/deuterium exchange mass spectrometry for probing higher order structure of protein therapeutics: methodology and applications. Drug Discov Today. 2014;19:95–102. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2013.07.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jaiswal M, Washburn MP, Zybailov BL. Mass Spectrometry-Based Methods of Proteome Analysis. Reviews in Cell Biology and Molecular Medicine; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Muntel J, Xuan Y, Berger ST, Reiter L, Bachur R, Kentsis A. et al. Advancing Urinary Protein Biomarker Discovery by Data-Independent Acquisition on a Quadrupole-Orbitrap Mass Spectrometer. J Proteome Res. 2015;14:4752–62. doi: 10.1021/acs.jproteome.5b00826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schwamborn K, Caprioli RM. Molecular imaging by mass spectrometry — looking beyond classical histology. Nat Rev Cancer. 2010;10:639–46. doi: 10.1038/nrc2917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Aichler M, Walch A. MALDI Imaging mass spectrometry: current frontiers and perspectives in pathology research and practice. Lab Invest. 2015;95:422–31. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.2014.156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Milman BL. General principles of identification by mass spectrometry. Trends Analyt Chem. 2015;69:24–33. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Antohe F. Mass Spectrometry based proteomics. Acta Endocrinol (Copenh) 2015;11:139–42. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Catherman AD, Skinner OS, Kelleher NL. Top Down proteomics: Facts and perspectives. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2014;445:683–93. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2014.02.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Klein O, Rohwer N, de Molina KF, Mergler S, Wessendorf P, Herrmann M. et al. Application of two-dimensional gel-based mass spectrometry to functionally dissect resistance to targeted cancer therapy. Proteomics Clin Appl. 2013;7:813–24. doi: 10.1002/prca.201300056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mao L. Seeing through the trick of cancer cells via 2D gels. Proteomics Clin Appl. 2013;7:723–4. doi: 10.1002/prca.201300111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rabilloud T, Lelong C. Two-dimensional gel electrophoresis in proteomics: A tutorial. J Proteomics. 2011;74:1829–41. doi: 10.1016/j.jprot.2011.05.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Oliveira BM, Coorssen JR, Martins-de-Souza D. 2DE: The Phoenix of Proteomics. J Proteomics. 2014;104:140–50. doi: 10.1016/j.jprot.2014.03.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rogowska-Wrzesinska A, Le Bihan M-C, Thaysen-Andersen M, Roepstorff P. 2D gels still have a niche in proteomics. J Proteomics. 2013;88:4–13. doi: 10.1016/j.jprot.2013.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Colignon B, Raes M, Dieu M, Delaive E, Mauro S. Evaluation of three-dimensional gel electrophoresis to improve quantitative profiling of complex proteomes. Proteomics. 2013;13:2077–82. doi: 10.1002/pmic.201200494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Liu Y, Hüttenhain R, Collins B, Aebersold R. Mass spectrometric protein maps for biomarker discovery and clinical research. Expert Rev Mol Diagn. 2013;13:811–25. doi: 10.1586/14737159.2013.845089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Frese CK, Altelaar AM, Hennrich ML, Nolting D, Zeller M, Griep-Raming J. et al. Improved peptide identification by targeted fragmentation using CID, HCD and ETD on an LTQ-Orbitrap Velos. J Proteome Res. 2011;10:2377–88. doi: 10.1021/pr1011729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Aebersold R, Mann M. Mass-spectrometric exploration of proteome structure and function. Nature. 2016;537:347–55. doi: 10.1038/nature19949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wu JX, Song X, Pascovici D, Zaw T, Care N, Krisp C. et al. SWATH Mass Spectrometry Performance Using Extended Peptide MS/MS Assay Libraries. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2016;15:2501–14. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M115.055558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Picotti P, Clement-Ziza M, Lam H, Campbell DS, Schmidt A, Deutsch EW. et al. A complete mass-spectrometric map of the yeast proteome applied to quantitative trait analysis. Nature. 2013;494:266–70. doi: 10.1038/nature11835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kim M-S, Pinto SM, Getnet D, Nirujogi RS, Manda SS, Chaerkady R. et al. A draft map of the human proteome. Nature. 2014;509:575–81. doi: 10.1038/nature13302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhang Q, Fillmore TL, Schepmoes AA, Clauss TR, Gritsenko MA, Mueller PW. et al. Serum proteomics reveals systemic dysregulation of innate immunity in type 1 diabetes. J Exp Med. 2013;210:191–203. doi: 10.1084/jem.20111843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Overgaard AJ, Thingholm TE, Larsen MR, Tarnow L, Rossing P, McGuire JN. et al. Quantitative iTRAQ-based proteomic identification of candidate biomarkers for diabetic nephropathy in plasma of type 1 diabetic patients. Clin Proteom. 2010;6:105. doi: 10.1007/s12014-010-9053-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chan KCA, Jiang P, Zheng YWL, Liao GJW, Sun H, Wong J. et al. Cancer Genome Scanning in Plasma: Detection of Tumor-Associated Copy Number Aberrations, Single-Nucleotide Variants, and Tumoral Heterogeneity by Massively Parallel Sequencing. Clin Chem. 2013;59:211–24. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2012.196014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yu L, Shen J, Mannoor K, Guarnera M, Jiang F. Identification of ENO1 As a Potential Sputum Biomarker for Early-Stage Lung Cancer by Shotgun Proteomics. Clin Lung Cancer. 2014;15:372–8.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.cllc.2014.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Shao S, Guo T, Aebersold R. Mass spectrometry-based proteomic quest for diabetes biomarkers. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2015;1854:519–27. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2014.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Leprevost FV, Valente RH, Lima DB, Perales J, Melani R, Yates JR. et al. PepExplorer: A Similarity-driven Tool for Analyzing de Novo Sequencing Results. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2014;13:2480–9. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M113.037002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Chick JM, Deepak Kolippakkam, David P. Nusinow, Bo Zhai, Ramin Rad, Edward L. Huttlin, and Steven P. Gygi.. An ultra-tolerant database search reveals that a myriad of modified peptides contributes to unassigned spectra in shotgun proteomics. Nat Biotechnol. 2015;33:743–9. doi: 10.1038/nbt.3267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Aebersold R, Bensimon A, Collins BC, Ludwig C, Sabido E. Applications and Developments in Targeted Proteomics: From SRM to DIA/SWATH. Proteomics. 2016;16:2065–7. doi: 10.1002/pmic.201600203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Manes NP, Nita-Lazar A. The development of SRM assays is transforming proteomics research. Proteomics; 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Picotti P, Aebersold R. Selected reaction monitoring-based proteomics: workflows, potential, pitfalls and future directions. Nat Methods. 2012;9:555–66. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gallien S, Bourmaud A, Kim SY, Domon B. Technical considerations for large-scale parallel reaction monitoring analysis. J Proteomics. 2014;100:147–59. doi: 10.1016/j.jprot.2013.10.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ahsan N, Rao RSP, Gruppuso PA, Ramratnam B, Salomon AR. Targeted proteomics: Current status and future perspectives for quantification of food allergens. J Proteomics. 2016;143:15–23. doi: 10.1016/j.jprot.2016.04.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Liu NQ, Dekker LJM, Van Duijn MM, Umar A. Use of Universal Stable Isotope Labeling by Amino Acids in Cell Culture (SILAC)-Based Selected Reaction Monitoring (SRM) Approach for Verification of Breast Cancer-Related Protein Markers. In: Martins-de-Souza D, editor. Shotgun Proteomics: Methods and Protocols. New York, NY: Springer New York. 2014:307–22. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-0685-7_21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Liebler DC, Zimmerman LJ. Targeted Quantitation of Proteins by Mass Spectrometry. Biochemistry. 2013;52:3797–806. doi: 10.1021/bi400110b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Newsome GA, Scholl PF. Quantification of Allergenic Bovine Milk αS1-Casein in Baked Goods Using an Intact 15N-Labeled Protein Internal Standard. J Agric Food Chem. 2013;61:5659–68. doi: 10.1021/jf3015238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Gallien S, Duriez E, Domon B. Selected reaction monitoring applied to proteomics. J Mass Spectrom. 2011;46:298–312. doi: 10.1002/jms.1895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Croote D, Quake SR. Food allergen detection by mass spectrometry: the role of systems biology. NPJ Syst Biol Appl. 2016;2:16022. doi: 10.1038/npjsba.2016.22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Costenoble R, Picotti P, Reiter L, Stallmach R, Heinemann M, Sauer U, Comprehensive quantitative analysis of central carbon and amino-acid metabolism in Saccharomyces cerevisiae under multiple conditions by targeted proteomics. Mol Syst Biol; 2011. p. 7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hu LZ, Zhang WP, Zhou MT, Han QQ, Gao XL, Zeng HL. et al. Analysis of Salmonella PhoP/PhoQ regulation by dimethyl-SRM-based quantitative proteomics. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2016;1864:20–8. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2015.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Gingras AC, Wong CJJ. Proteomics approaches to decipher new signaling pathways. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2016;41:128–34. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2016.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wohlgemuth I, Lenz C, Urlaub H. Studying macromolecular complex stoichiometries by peptide-based mass spectrometry. Proteomics. 2015;15:862–79. doi: 10.1002/pmic.201400466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Huang YA, You ZH, Li X, Chen X, Hu P, Li S. et al. Construction of reliable protein-protein interaction networks using weighted sparse representation based classifier with pseudo substitution matrix representation features. Neurocomputing. 2016;218:131–8. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Angeleri M, Muth-Pawlak D, Aro EM, Battchikova N. Study of O-Phosphorylation Sites in Proteins Involved in Photosynthesis-Related Processes in Synechocystis sp. Strain PCC 6803: Application of the SRM Approach. J Proteome Res; 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Gallien S, Duriez E, Demeure K, Domon B. Selectivity of LC-MS/MS analysis: Implication for proteomics experiments. J Proteomics. 2013;81:148–58. doi: 10.1016/j.jprot.2012.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Gallien S, Peterman S, Kiyonami R, Souady J, Duriez E, Schoen A. et al. Highly multiplexed targeted proteomics using precise control of peptide retention time. Proteomics. 2012;12:1122–33. doi: 10.1002/pmic.201100533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Peterson AC, Russell JD, Bailey DJ, Westphall MS, Coon JJ. Parallel Reaction Monitoring for High Resolution and High Mass Accuracy Quantitative, Targeted Proteomics. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2012;11:1475–88. doi: 10.1074/mcp.O112.020131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Law KP, Lim YP. Recent advances in mass spectrometry: data independent analysis and hyper reaction monitoring. Expert Rev Proteomics. 2013;10:551–66. doi: 10.1586/14789450.2013.858022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Gillet LC, Navarro P, Tate S, Röst H, Selevsek N, Reiter L. et al. Targeted Data Extraction of the MS/MS Spectra Generated by Data-independent Acquisition: A New Concept for Consistent and Accurate Proteome Analysis. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2012;11:O111.016717. doi: 10.1074/mcp.O111.016717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Selevsek N, Chang CY, Gillet LC, Navarro P, Bernhardt OM, Reiter L. et al. Reproducible and Consistent Quantification of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae Proteome by SWATH-mass spectrometry. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2015;14:739–49. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M113.035550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Huang Q, Yang L, Luo J, Guo L, Wang Z, Yang X. et al. SWATH enables precise label-free quantification on proteome scale. Proteomics. 2015;15:1215–23. doi: 10.1002/pmic.201400270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Liu Y, Chen J, Sethi A, Li QK, Chen L, Collins B. et al. Glycoproteomic Analysis of Prostate Cancer Tissues by SWATH Mass Spectrometry Discovers N-acylethanolamine Acid Amidase and Protein Tyrosine Kinase 7 as Signatures for Tumor Aggressiveness. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2014;13:1753–68. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M114.038273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Liu Y, Hüttenhain R, Surinova S, Gillet LCJ, Mouritsen J, Brunner R. et al. Quantitative measurements of N-linked glycoproteins in human plasma by SWATH-MS. Proteomics. 2013;13:1247–56. doi: 10.1002/pmic.201200417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Gao Y, Wang X, Sang Z, Li Z, Liu F, Mao J. et al. Quantitative proteomics by SWATH-MS reveals sophisticated metabolic reprogramming in hepatocellular carcinoma tissues. Sci Rep. 2017;7:45913. doi: 10.1038/srep45913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Ortea I, Rodríguez-Ariza A, Chicano-Gálvez E, Arenas Vacas MS, Jurado Gámez B. Discovery of potential protein biomarkers of lung adenocarcinoma in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid by SWATH MS data-independent acquisition and targeted data extraction. J Proteomics. 2016;138:106–14. doi: 10.1016/j.jprot.2016.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Selevsek N, Chang CY, Gillet LC, Navarro P, Bernhardt OM, Reiter L. et al. Reproducible and consistent quantification of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae proteome by SWATH-mass spectrometry. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2015;14:739–49. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M113.035550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Colgrave M L BK, Blundell M. et al. Comparing Multiple Reaction Monitoring and Sequential Window Acquisition of All Theoretical Mass Spectra for the Relative Quantification of Barley Gluten in Selectively Bred Barley Lines. Anal Chem. 2016;88:9127–35. doi: 10.1021/acs.analchem.6b02108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Tsou CC, Avtonomov D, Larsen B, Tucholska M, Choi H, Gingras AC. et al. DIA-Umpire: comprehensive computational framework for data-independent acquisition proteomics. Nat Methods. 2015;12:258–64. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.3255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Zi J, Zhang S, Zhou R, Zhou B, Xu S, Hou G. et al. Expansion of the ion library for mining SWATH-MS data through fractionation proteomics. Anal Chem. 2014;86:7242–6. doi: 10.1021/ac501828a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Röst HL, Rosenberger G, Navarro P, Gillet L, Miladinović SM, Schubert OT. et al. OpenSWATH enables automated, targeted analysis of data-independent acquisition MS data. Nat Biotechnol. 2014;32:219–23. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Schubert OT, Gillet LC, Collins BC, Navarro P, Rosenberger G, Wolski WE. et al. Building high-quality assay libraries for targeted analysis of SWATH MS data. Nat Protoc. 2015;10:426–41. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2015.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Egertson JD, Kuehn A, Merrihew GE, Bateman NW, MacLean BX, Ting YS. et al. Multiplexed MS/MS for improved data-independent acquisition. Nat Methods. 2013;10:744–6. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Weisbrod CR, Eng JK, Hoopmann MR, Baker T, Bruce JE. Accurate Peptide Fragment Mass Analysis: Multiplexed Peptide Identification and Quantification. J Proteome Res. 2012;11:1621–32. doi: 10.1021/pr2008175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Law KP, Lim YP. Recent advances in mass spectrometry: data independent analysis and hyper reaction monitoring. Expert Rev Proteomics. 2013;10:551–66. doi: 10.1586/14789450.2013.858022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Kang C, Lee Y, Lee JE. Recent advances in mass spectrometry-based proteomics of gastric cancer. World J Gastroenterol. 2016;22:8283–93. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v22.i37.8283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2015. CA Cancer J Clin. 2015;65:5–29. doi: 10.3322/caac.21254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Cui J, Chen Y, Chou W-C, Sun L, Chen L, Suo J. et al. An integrated transcriptomic and computational analysis for biomarker identification in gastric cancer. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39:1197–207. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Xiao H, Zhang Y, Kim Y, Kim S, Kim JJ, Kim KM. et al. Differential Proteomic Analysis of Human Saliva using Tandem Mass Tags Quantification for Gastric Cancer Detection. Sci Rep. 2016;6:22165. doi: 10.1038/srep22165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Pan S, Brentnall TA, Kelly K, Chen R. Tissue proteomics in pancreatic cancer study: Discovery, emerging technologies, and challenges. Proteomics. 2013;13:710–21. doi: 10.1002/pmic.201200319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Werner S, Chen H, Tao S, Brenner H. Systematic review: Serum autoantibodies in the early detection of gastric cancer. Int J Cancer. 2015;136:2243–52. doi: 10.1002/ijc.28807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Liu R, Zhang C, Hu Z, Li G, Wang C, Yang C. et al. A five-microRNA signature identified from genome-wide serum microRNA expression profiling serves as a fingerprint for gastric cancer diagnosis. Eur J Cancer. 2011;47:784–91. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2010.10.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Toiyama Y, Okugawa Y, Goel A. DNA methylation and microRNA biomarkers for noninvasive detection of gastric and colorectal cancer. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2014;455:43–57. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2014.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Hu W, Wang J, Luo G, Luo B, Wu C, Wang W, Proteomics-based analysis of differentially expressed proteins in the CXCR1-knockdown gastric carcinoma MKN45 cell line and its parental cell. Acta Biochim Biophys Sin (Shanghai); 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Yang J, Xiong X, Wang X, Guo B, He K, Huang C. Identification of peptide regions of SERPINA1 and ENOSF1 and their protein expression as potential serum biomarkers for gastric cancer. Tumor Biol. 2015;36:5109–18. doi: 10.1007/s13277-015-3163-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Wu W, Chung MCM. The gastric fluid proteome as a potential source of gastric cancer biomarkers. J Proteomics. 2013;90:3–13. doi: 10.1016/j.jprot.2013.04.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Wu W, Yong WW, Chung MCM. A simple biomarker scoring matrix for early gastric cancer detection. Proteomics. 2016;16:2921–30. doi: 10.1002/pmic.201600194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Catenacci DVT, Liao WL, Zhao L, Whitcomb E, Henderson L, O'Day E. et al. Mass-spectrometry-based quantitation of Her2 in gastroesophageal tumor tissue: comparison to IHC and FISH. Gastric Cancer. 2016;19:1066–79. doi: 10.1007/s10120-015-0566-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Chen JF, Zhu Y, Lu YT, Hodara E, Shuang H, Agopian VG. et al. Clinical Applications of NanoVelcro Rare-Cell Assays for Detection and Characterization of Circulating Tumor Cells. Theranostics. 2016;6:1425. doi: 10.7150/thno.15359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Gao W, Xu J, Wang F, Zhang L, Peng R, Shu Y. et al. Plasma membrane proteomic analysis of human Gastric Cancer tissues: revealing flotillin 1 as a marker for Gastric Cancer. BMC Cancer. 2015;15:367. doi: 10.1186/s12885-015-1343-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Zhang K, Shi H, Xi H, Wu X, Cui J, Gao Y. et al. Genome-Wide lncRNA Microarray Profiling Identifies Novel Circulating lncRNAs for Detection of Gastric Cancer. Theranostics. 2017;7:213–27. doi: 10.7150/thno.16044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Gao W, Xu J, Wang F, Zhang L, Peng R, Zhu Y. et al. Mitochondrial Proteomics Approach Reveals Voltage-Dependent Anion Channel 1 (VDAC1) as a Potential Biomarker of Gastric Cancer. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2015;37:2339–54. doi: 10.1159/000438588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Kreso A, Dick John E. Evolution of the Cancer Stem Cell Model. Cell Stem Cell. 2014;14:275–91. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2014.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Cojoc M, Mäbert K, Muders MH, Dubrovska A. A role for cancer stem cells in therapy resistance: Cellular and molecular mechanisms. Semin Cancer Biol. 2015;31:16–27. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2014.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Yashiro M, Morisaki T, Hasegawa T, Kakehashi A, Kinoshita H, Fukuoka T. et al. Abstract 1405: Novel biomarkers for gastric cancer stem cells utilizing comparative proteomics analysis. Cancer Res. 2015;75:1405–1405. [Google Scholar]

- 106.Kato K, Kamada H, Fujimori T, Aritomo Y, Ono M, Masaki T. Molecular Biologic Approach to the Diagnosis of Pancreatic Carcinoma Using Specimens Obtained by EUS-Guided Fine Needle Aspiration. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2012;2012:7. doi: 10.1155/2012/243524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Yadav D, Lowenfels AB. The Epidemiology of Pancreatitis and Pancreatic Cancer. Gastroenterology. 2013;144:1252–61. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2013.01.068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Lin C, Wu WC, Zhao GC, Wang DS, Lou WH, Jin DY. ITRAQ-based quantitative proteomics reveals apolipoprotein A-I and transferrin as potential serum markers in CA19-9 negative pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Medicine. 2016;95:e4527. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000004527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Humphris JL, Chang DK, Johns AL, Scarlett CJ, Pajic M, Jones MD. et al. The prognostic and predictive value of serum CA19.9 in pancreatic cancer. Ann Oncol. 2012;23:1713–22. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdr561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Magnani JL, Steplewski Z, Koprowski H, Ginsburg V. Identification of the Gastrointestinal and Pancreatic Cancer-associated Antigen Detected by Monoclonal Antibody 19-9 in the Sera of Patients as a Mucin. Cancer Res. 1983;43:5489–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Tempero MA, Uchida E, Takasaki H, Burnett DA, Steplewski Z, Pour PM. Relationship of Carbohydrate Antigen 19-9 and Lewis Antigens in Pancreatic Cancer. Cancer Res. 1987;47:5501–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Yoneyama T, Ohtsuki S, Honda K, Kobayashi M, Iwasaki M, Uchida Y. et al. Identification of IGFBP2 and IGFBP3 As Compensatory Biomarkers for CA19-9 in Early-Stage Pancreatic Cancer Using a Combination of Antibody-Based and LC-MS/MS-Based Proteomics. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0161009. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0161009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Zhong N, Cui Y, Zhou X, Li T, Han J. Identification of prohibitin 1 as a potential prognostic biomarker in human pancreatic carcinoma using modified aqueous two-phase partition system combined with 2D-MALDI-TOF-TOF-MS/MS. Tumor Biol. 2015;36:1221–31. doi: 10.1007/s13277-014-2742-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Takadate T, Onogawa T, Fukuda T, Motoi F, Suzuki T, Fujii K. et al. Novel prognostic protein markers of resectable pancreatic cancer identified by coupled shotgun and targeted proteomics using formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tissues. Int J Cancer. 2013;132:1368–82. doi: 10.1002/ijc.27797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Jemal A, Bray F, Center MM, Ferlay J, Ward E, Forman D. Global cancer statistics. CA Cancer J Clin. 2011;61:69–90. doi: 10.3322/caac.20107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Kimhofer T, Fye H, Taylor-Robinson S, Thursz M, Holmes E. Proteomic and metabonomic biomarkers for hepatocellular carcinoma: a comprehensive review. Br J Cancer. 2015;112:1141–56. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2015.38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Naboulsi W MDA, Bracht T, Naboulsi W, Megger D A, Bracht T. et al. Quantitative tissue proteomics analysis reveals versican as potential biomarker for early-stage hepatocellular carcinoma. J Proteome Res. 2015;15:38–47. doi: 10.1021/acs.jproteome.5b00420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.D.A. Megger TB, M. Kohl, M. Ahrens, W. Naboulsi, F. Weber, A.C. Hoffmann, C. Stephan, K. Kuhlmann, M. Eisenacher, J.F. Schlaak, H.A. Baba, H.E. Meyer, B. Sitek. Proteomic differences between hepatocellular carcinoma and non-tumorous liver tissue investigated by a combined 2D-DIGE and label-free quantitative proteomics study. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2013;12:2006–20. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M113.028027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Reis H, Pütter C, Megger DA, Bracht T, Weber F, Hoffmann A-C. et al. A structured proteomic approach identifies 14-3-3Sigma as a novel and reliable protein biomarker in panel based differential diagnostics of liver tumors. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2015;1854:641–50. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2014.10.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Wang RC, Huang CY, Pan TL, Chen WY, Ho CT, Liu TZ. et al. Proteomic Characterization of Annexin l (ANX1) and Heat Shock Protein 27 (HSP27) as Biomarkers for Invasive Hepatocellular Carcinoma Cells. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0139232. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0139232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Siegel R, Naishadham D, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2012. CA Cancer J Clin. 2012;62:10–29. doi: 10.3322/caac.20138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Parente F, Vailati C, Boemo C, Bonoldi E, Ardizzoia A, Ilardo A. et al. Improved 5-year survival of patients with immunochemical faecal blood test-screen-detected colorectal cancer versus non-screening cancers in northern Italy. Dig Liver Dis. 2015;47:68–72. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2014.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Wang Y, Shan Q, Hou G, Zhang J, Bai J, Lv X. et al. Discovery of potential colorectal cancer serum biomarkers through quantitative proteomics on the colonic tissue interstitial fluids from the AOM-DSS mouse model. J Proteomics. 2016;132:31–40. doi: 10.1016/j.jprot.2015.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Surinova S, Radová L, Choi M, Srovnal J, Brenner H, Vitek O. et al. Non-invasive prognostic protein biomarker signatures associated with colorectal cancer. EMBO Mol Med. 2015;7:1153–65. doi: 10.15252/emmm.201404874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Tomonaga T, Kume H. Biomarker Discovery of Colorectal Cancer Using Membrane Proteins Extracted from Cancer Tissues. Rinsho byori. 2015;63:322–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Bosch LJ, de Wit M, Hiemstra AC, Piersma S, Pham T, Oudgenoeg G. et al. Abstract 1563: Stool proteomics reveals novel candidate biomarkers for colorectal cancer screening. Cancer Res. 2015;75:1563–1563. [Google Scholar]

- 127.Peltier J, Roperch JP, Audebert S, Borg JP, Camoin L. Quantitative proteomic analysis exploring progression of colorectal cancer: Modulation of the serpin family. J Proteomics. 2016;148:139–48. doi: 10.1016/j.jprot.2016.07.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Sun Y, Yang Y, Shen H, Huang M, Wang Z, Liu Y. et al. iTRAQ-based chromatin proteomic screen reveals CHD4-dependent recruitment of MBD2 to sites of DNA damage. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2016;471:142–8. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2016.01.162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Smith SJ, Kroon JTM, Simon WJ, Slabas AR, Chivasa S. A novel function for Arabidopsis CYCLASE1 in programmed cell death revealed by iTRAQ analysis of extracellular matrix proteins. Mol Cell Proteomics; 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Evans C, Noirel J, Ow SY, Salim M, Pereira-Medrano AG, Couto N. et al. An insight into iTRAQ: where do we stand now? Anal Bioanal Chem. 2012;404:1011–27. doi: 10.1007/s00216-012-5918-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Pinho SS, Reis CA. Glycosylation in cancer: mechanisms and clinical implications. Nat Rev Cancer. 2015;15:540–55. doi: 10.1038/nrc3982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Miwa HE, Koba WR, Fine EJ, Giricz O, Kenny PA, Stanley P. Bisected, complex N-glycans and galectins in mouse mammary tumor progression and human breast cancer. Glycobiology; 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Christiansen MN, Chik J, Lee L, Anugraham M, Abrahams JL, Packer NH. Cell surface protein glycosylation in cancer. Proteomics. 2014;14:525–46. doi: 10.1002/pmic.201300387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Zhang Y, Jiao J, Yang P, Lu H. Mass spectrometry-based N-glycoproteomics for cancer biomarker discovery. Clin Proteomics. 2014;11:18. doi: 10.1186/1559-0275-11-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Sethi M K HWS, Fanayan S. Identifying N-Glycan Biomarkers in Colorectal Cancer by Mass Spectrometry. Acc Chem Res. 2016;49:2099–106. doi: 10.1021/acs.accounts.6b00193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Koshiyama A, Ichibangase T, Imai K. Comprehensive fluorogenic derivatization-liquid chromatography/tandem mass spectrometry proteomic analysis of colorectal cancer cell to identify biomarker candidate. Biomed Chromatogr. 2013;27:440–50. doi: 10.1002/bmc.2811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Reck M, Popat S, Reinmuth N, De Ruysscher D, Kerr KM, Peters S. Metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC): ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol; 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Siegel R, Naishadham D, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2013. CA Cancer J Clin. 2013;63:11–30. doi: 10.3322/caac.21166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Wang CL, Wang CI, Liao PC, Chen CD, Liang Y, Chuang WY. et al. Discovery of retinoblastoma-associated binding protein 46 as a novel prognostic marker for distant metastasis in nonsmall cell lung cancer by combined analysis of cancer cell secretome and pleural effusion proteome. J Proteome Res. 2009;8:4428–40. doi: 10.1021/pr900160h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Wang Z, Wang C, Huang X, Shen Y, Shen J, Ying K. Differential proteome profiling of pleural effusions from lung cancer and benign inflammatory disease patients. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2012;1824:692–700. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2012.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Li Y, Lian H, Jia Q, Wan Y. Proteome screening of pleural effusions identifies IL1A as a diagnostic biomarker for non-small cell lung cancer. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2015;457:177–82. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2014.12.083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Na SS, Aldonza MB, Sung HJ, Kim YI, Son YS, Cho S. et al. Stanniocalcin-2 (STC2): A potential lung cancer biomarker promotes lung cancer metastasis and progression. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2015;1854:668–76. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2014.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.An J, Tang C, Wang N, Liu Y, Guo W, Li X. et al. Preliminary study of MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry-based screening of patients with the NSCLC serum-specific peptides. Zhongguo Fei Ai Za Zhi. 2013;16:233–9. doi: 10.3779/j.issn.1009-3419.2013.05.04. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Chouaib S, Kieda C, Benlalam H, Noman MZ, Mami-Chouaib F, Ruegg C. Endothelial Cells as Key Determinants of the Tumor Microenvironment: Interaction with Tumor Cells, Extracellular Matrix and Immune Killer Cells. Crit Rev Immunol. 2010;30:529–45. doi: 10.1615/critrevimmunol.v30.i6.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.Reymond N, d'Agua BB, Ridley AJ. Crossing the endothelial barrier during metastasis. Nat Rev Cancer. 2013;13:858–70. doi: 10.1038/nrc3628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146.Matsuda K, Ohga N, Hida Y, Muraki C, Tsuchiya K, Kurosu T. et al. Isolated tumor endothelial cells maintain specific character during long-term culture. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2010;394:947–54. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2010.03.089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147.Zhuo H, Lyu Z, Su J, He J, Pei Y, Cheng X. et al. Effect of Lung Squamous Cell Carcinoma Tumor Microenvironment on the CD105+ Endothelial Cell Proteome. J Proteome Res. 2014;13:4717–29. doi: 10.1021/pr5006229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148.Jin H, Cheng X, Pei Y, Fu J, Lyu Z, Peng H. et al. Identification and verification of transgelin-2 as a potential biomarker of tumor-derived lung-cancer endothelial cells by comparative proteomics. J Proteomics. 2016;136:77–88. doi: 10.1016/j.jprot.2015.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149.Rovithi M, Lind JSW, Pham TV, Voortman J, Knol JC, Verheul HMW. et al. Response and toxicity prediction by MALDI-TOF-MS serum peptide profiling in patients with non-small cell lung cancer. Proteomics Clin Appl. 2016;10:743–9. doi: 10.1002/prca.201600025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 150.Walker MJ, Zhou C, Backen A, Pernemalm M, Williamson AJK, Priest LJC. et al. Discovery and Validation of Predictive Biomarkers of Survival for Non-small Cell Lung Cancer Patients Undergoing Radical Radiotherapy: Two Proteins With Predictive Value. EBioMedicine. 2015;2:841–50. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2015.06.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 151.Birse CE, Lagier RJ, FitzHugh W, Pass HI, Rom WN, Edell ES. et al. Blood-based lung cancer biomarkers identified through proteomic discovery in cancer tissues, cell lines and conditioned medium. Clin Proteomics. 2015;12:18. doi: 10.1186/s12014-015-9090-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 152.Xiao H, Zhang L, Zhou H, Lee JM, Garon EB, Wong DTW. Proteomic analysis of human saliva from lung cancer patients using two-dimensional difference gel electrophoresis and mass spectrometry. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2012;11:M111.012112. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M111.012112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 153.Vargas AJ, Harris CC. Biomarker development in the precision medicine era: lung cancer as a case study. Nat Rev Cancer. 2016;16:525–37. doi: 10.1038/nrc.2016.56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 154.Kim YJ, Sertamo K, Pierrard M-A, Mesmin C, Kim SY, Schlesser M. et al. Verification of the biomarker candidates for non-small-cell lung cancer using a targeted proteomics approach. J Proteome Res. 2015;14:1412–9. doi: 10.1021/pr5010828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 155.Hong S, Kang YA, Cho BC, Kim DJ. Elevated Serum C-Reactive Protein as a Prognostic Marker in Small Cell Lung Cancer. Yonsei Med J. 2012;53:111–7. doi: 10.3349/ymj.2012.53.1.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 156.Ryan BM, Pine SR, Chaturvedi AK, Caporaso N, Harris CC. A Combined Prognostic Serum Interleukin-8 and Interleukin-6 Classifier for Stage 1 Lung Cancer in the Prostate, Lung, Colorectal, and Ovarian Cancer Screening Trial. J Thorac Oncol. 2014;9:1494–503. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0000000000000278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 157.Song G, Liu Y, Wang Y, Ren G, Guo S, Ren J. et al. Personalized biomarkers to monitor disease progression in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer patients treated with icotinib. Clin Chim Acta. 2015;440:44–8. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2014.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 158.Barrera L, Montes-Servín E, Barrera A, Ramírez-Tirado LA, Salinas-Parra F, Bañales-Méndez JL. et al. Cytokine profile determined by data-mining analysis set into clusters of non-small-cell lung cancer patients according to prognosis. Ann Oncol. 2015;26:428–35. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdu549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 159.Sengupta D, Tackett AJ. Proteomic Findings in Melanoma. J Proteomics Bioinform. 2016;9:e29. doi: 10.4172/jpb.1000e29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 160.Byrum SD, Larson SK, Avaritt NL, Moreland LE, Mackintosh SG, Cheung WL. et al. Quantitative Proteomics Identifies Activation of Hallmark Pathways of Cancer in Patient Melanoma. J Proteomics Bioinform. 2013;6:043–50. doi: 10.4172/jpb.1000260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 161.Qendro V, Lundgren DH, Rezaul K, Mahony F, Ferrell N, Bi A. et al. Large-Scale Proteomic Characterization of Melanoma Expressed Proteins Reveals Nestin and Vimentin as Biomarkers That Can Potentially Distinguish Melanoma Subtypes. J Proteome Res. 2014;13:5031–40. doi: 10.1021/pr5006789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 162.Yuana Y, Sturk A, Nieuwland R. Extracellular vesicles in physiological and pathological conditions. Blood Rev. 2013;27:31–9. doi: 10.1016/j.blre.2012.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 163.Riches A, Campbell E, Borger E, Powis S. Regulation of exosome release from mammary epithelial and breast cancer cells - A new regulatory pathway. Eur J Cancer. 2014;50:1025–34. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2013.12.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 164.Ekström EJ, Bergenfelz C, von Bülow V, Serifler F, Carlemalm E, Jönsson G. et al. WNT5A induces release of exosomes containing pro-angiogenic and immunosuppressive factors from malignant melanoma cells. Mol Cancer. 2014;13:88. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-13-88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 165.Hood JL, San RS, Wickline SA. Exosomes Released by Melanoma Cells Prepare Sentinel Lymph Nodes for Tumor Metastasis. Cancer Res. 2011;71:3792–801. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-4455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 166.Peinado H, Aleckovic M, Lavotshkin S, Matei I, Costa-Silva B, Moreno-Bueno G. et al. Melanoma exosomes educate bone marrow progenitor cells toward a pro-metastatic phenotype through MET. Nat Med. 2012;18:883–91. doi: 10.1038/nm.2753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 167.Lazar I, Clement E, Ducoux-Petit M, Denat L, Soldan V, Dauvillier S. et al. Proteome characterization of melanoma exosomes reveals a specific signature for metastatic cell lines. Pigment Cell Melanoma Res. 2015;28:464–75. doi: 10.1111/pcmr.12380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 168.Angi M, Kalirai H, Coupland S. Proteomic analysis of the uveal melanoma (UM) secretome reveals novel insights and potential biomarkers. Acta Ophthalmol (Copenh); 2015. p. 93. [Google Scholar]

- 169.Crabb JW, Hu B, Crabb JS, Triozzi P, Saunthararajah Y, Tubbs R. et al. iTRAQ Quantitative Proteomic Comparison of Metastatic and Non-Metastatic Uveal Melanoma Tumors. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0135543. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0135543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 170.Mittal P JM. Proteomics: An Indispensable Tool for Novel Biomarker Identification in Melanoma. J Data Mining Genomics Proteomics. 2016;7:204. [Google Scholar]

- 171.Mahfoud OK, Rakovich TY, Prina-Mello A, Movia D, Alves F, Volkov Y. Detection of ErbB2: nanotechnological solutions for clinical diagnostics. RSC Adv. 2014;4:3422–42. [Google Scholar]