Abstract

Objective

To compare neurocognition and quality-of-life (QoL) in a group of children and adolescents with or without growth hormone deficiency (GHD) following moderate-to-severe traumatic brain injury (TBI).

Study designs

Thirty-two children and adolescents were recruited from the TBI clinic at a children’s hospital. Growth hormone (GH) was measured by both spontaneous overnight testing and following arginine/glucagon stimulation administration. Twenty-nine subjects participated in extensive neuropsychological assessment.

Results

GHD as measured on overnight testing was significantly associated with a variety of neurocognitive and QoL measures. Specifically, subjects with GHD had significantly (p<0.05) lower scores on measures of visual memory and health-related quality-of-life. These scores were not explained by severity of injury or IQ (p>0.05). GHD noted in response to provocative testing was not associated with any neurocognitive or QoL measures.

Conclusions

GHD following TBI is common in children and adolescents. Deficits in neurocognition and QoL impact recovery after TBI. It is important to assess potential neurocognitive and QoL changes that may occur as a result of GHD. It is also important to consider the potential added benefit of overnight GH testing as compared to stimulation testing in predicting changes in neurocognition or QoL.

Keywords: Brain injury, growth hormone deficiency, neuropsychology, quality-of-life, cognition

Introduction

Neuropsychological deficits (neurobehavioural alterations and neurocognitive changes) are recognized to be some of the most enduring forms of injury and possibly the most disqualifying limitations for opportunity of life [1]. The role of neuroendocrine abnormalities in the neurocognitive functioning of children and adolescents who sustained a traumatic brain injury (TBI) is not well understood. This prospective study sought to better understand the relationship between growth hormone deficiency (GHD) and the neuropsychological recovery of children and adolescents following moderate-to-severe TBI. Although growth hormone (GH) is traditionally thought of for its role in achieving normal height [2], the effects that GH may exert in the brain have received increasing attention in recent years. Specifically, studies have evaluated the effects of GH on appetite, cognitive functions, energy, memory, mood, sleep and well-being or qualityof-life [3].

The prevalence of neuroendocrine abnormalities following TBI is becoming better understood. Neuroendocrine dysfunction has been found in both the acute phase as well as several months or longer following the event [4]. Reported rates of pituitary dysfunction after TBI vary. Studies in adults indicate that at least 25% of patients with moderate-to-severe brain injury have some degree of hypopituitarism in the chronic phase after TBI [4–6]. The hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal and GH axes are most frequently affected [7–9]. Niederland et al. [10] found pituitary dysfunction in 61% of children (mean age 11.47_0.75 years) who most often showed no obvious clinical symptoms of abnormal pituitary function. However, the data regarding the natural history and frequency of GHD in children following TBI is limited [11]. Based on studies that explore the prevalence of neuroendocrine abnormalities following TBI, it has been recommended that screening of pituitary function should always be performed following TBI [6, 7, 10, 12–14]. In 2005, international experts in endocrinology developed a consensus statement that recommended systematic screening of pituitary function for all patients with moderate-to-severe TBI at risk of developing pituitary deficits [15]. These guidelines stem primarily from work with adults and the authors recommend further research to determine specific guidelines for children and adolescents.

Neuroendocrine abnormalities in adults produce an array of symptoms, including both physical and emotional/cognitive symptoms [4]. The cognitive influences of GH deficiency in the ageing population are well documented [16–18]. In adults, GH deficiency following TBI results in declines in executive functioning as well as attention, memory and emotion [19, 20]. Neuroendocrine functioning is especially important for children and adolescents because the child/adolescent brain experiences strong influences from the neuroendocrine systems for proper psychological development. Because the neurocognitive effects of neuroendocrine abnormalities are becoming better understood, GH replacement therapy has been administered to improve neurocognition. However, the literature on the cognitive effects of GH replacement is largely focused on adults. A meta-analysis of seven prospective studies investigating the cognitive effects of GH replacement therapy in adults without brain injury shows that it results in moderate improvements in cognitive performance, particularly attention and memory [21]. Other studies have not found improvements in cognitive functioning and psychological well-being after GH replacement [22, 23]. Falleti et al. [21] suggest that results may differ based on whether the study uses population normative data as compared to matched controls. The literature on GH replacement after TBI is very limited. Kreitschmann-Andermahr et al. [24] studied adults with GHD after TBI and found that GH replacement therapy can improve the QoL after TBI-related GHD (as measured by the Assessment of Growth Hormone Deficiency in Adults [AGHDA]). A better understanding of the neurocognitive effects of GHD in children and adolescents following moderate-to-severe TBI would help guide decision-making regarding this type of treatment. This study aims to identify the association of neurocognitive effects of GHD in children and adolescents following moderate-tosevere TBI.

Methods

Participants

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board. Children and adolescents aged 8–21 with a history of moderate-to-severe TBI were invited to enrol as they were evaluated for regular follow-up in the brain injury clinic at a rehabilitation centre. Prospective candidates were identified by the attending physician based on pre-determined criteria. Moderate-to-severe TBI was defined by one of two criteria: (1) a Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) of 12 or less or (2), in the absence of a GCS score, by a history suggestive that the GCS was in the target range, as well as abnormal findings on brain MRI related to the injury. All subjects, with the exception of one, had a GCS of 12 or less. The one subject with a GCS greater than 12 had positive MRI findings suggestive of a much more serious injury, including right frontal and right temporal diffuse axonal injury. Inclusion criteria also included freedom from medications or endocrine treatments that would affect GH and IGF-1 levels.

Procedures

After appropriate consent was obtained, pre-injury height, weight and BMI were determined by record review and/or parental history. Puberty stage was assessed and recorded as described by Tanner stage [25].

Hormone assays

The study participants were admitted to a General Clinical Research Centre (GCRC) for overnight blood sampling for GH concentrations. During this time, an IV catheter was placed and blood samples were drawn every 20 minutes from 20:00 until 08:00. In the morning, laboratory studies were obtained, including IGF-1, IGFBP-3, cortisol, insulin, TSH, estradiol, DHEA-S, testosterone, prolactin, FSH and LH. An arginine/glucagon GH stimulation test was then administered, using 0.5 g kg_1 of 10% arginine hydrochloride IV (maximum dose 20 g) and 0.02mg kg_1 of glucagon SC.

Growth hormone deficiency was diagnosed based on the presence of both a peak serum GH level on overnight testing of <5ngmL_1 and a peak GH level following arginine and glucagon of <7ngmL_1 for subjects <18 years old or <5ngmL_1 for subjects _18 years old. Subjects who did not secrete GH above these levels during provocative testing but had exhibited spontaneous GH release above these cutoff limits within 1 hour prior to the arginine/glucagon stimulation test were considered to have adequate GH reserve and were not classified as exhibiting inadequate response to provocative testing. The cut-off level for overnight testing was chosen based on results from overnight sampling in healthy children [26, 27], while the provocative testing cut-off was based on recommendations of the Lawson Wilkins Paediatric Endocrine Society and the European Society for Paediatric Endocrinology, adjusting for alterations in GH measurement using monoclonal antibody techniques [28, 29]. The cutoff for adolescents _18 years old was based on standards used to diagnose adult GHD [4]. The results were reviewed by the participating paediatric endocrinologist and classified as GHD on overnight and/or provocative testing. The endocrinologist also reviewed the results of the early morning laboratory tests of endocrine function and recommended which abnormal results should lead to additional samples prepared for assay and which should trigger referral to a non-study endocrinologist for further evaluation.

Laboratory samples were stored at _80_C and tested at the Core Laboratory of the GCRC using two-site chemiluminescence immunoassays on an Immulite 2000 (Diagnostic Products Corporation, Los Angeles, CA), according to the manufacturer’s specifications. For GH, the assay range is 0.05–40 ngmL_1. Intra-/inter-assay coefficients of variation for samples tested in this laboratory are as follows: growth hormone 3.3%/6.4%, IGF-1 2.8%/5.6%, free T4 4.7%/7.1%, TSH 3.9%/7.6%, LH 4.2%/6.2%, FSH 4.5%/6.8%, testosterone 6.8%/9.6%, estradiol 7.0%/5.4%, prolactin 2.1%/5.8% and DHEAS 6.0%/7.4%.

Neuropsychological tests

During the study visit, subjects participated in neuropsychological evaluation if able (see Table I for specific sub-tests administered from each test). Select sub-tests from the Wechsler Abbreviated Scale of Intelligence (WASI) [30], Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children, Fourth Edition (WISC-IV) [31, 32] or Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale–Third Edition (WAIS-III) [33], Wide Range Assessment of Memory and Learning, Second Edition (WRAML2) [34] and Delis Kaplan Executive Function System (D-KEFS) [35, 36] were administered by a clinical psychology postdoctoral fellow or a clinical psychologist. If subjects were unable to participate in neuropsychological testing, a Vineland Adaptive Behaviour Scales, Second Edition, Survey Interview (Vineland-II) [37] was conducted with the guardian. The guardians of all subjects completed the Child Health Questionnaire Parent Form 28 Questions (CHQ) [38] and Behaviour Rating Inventory of Executive Function, Parent Form (BRIEF) [39].

Table I.

Neuropsychological tests/indices and associated sub-tests administered. Name of test/index/sub-tests administered

| Wechsler Abbreviated Scale of Intelligence (WASI) |

| Verbal IQ |

| Vocabulary |

| Similarities |

| Performance IQ |

| Block Design |

| Matrix Reasoning |

| Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children, Fourth Edition (WISC-IV), 6–16;11 years |

| Coding |

| Letter Number Sequencing |

| Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale, Third Edition (WAIS-III), 16–89 years |

| Coding |

| Letter Number Sequencing |

| Wide Range Assessment of Memory and Learning, Second Edition (WRAML2) |

| Verbal Memory |

| Story Memory |

| Verbal Learning |

| Visual Memory |

| Design Memory |

| Picture Memory |

| Attention/Concentration |

| Finger Windows |

| Number Letter |

| Delay Recall |

| Story Memory Recall |

| Verbal Learning Recall |

| Verbal Recognition |

| Story Recognition |

| Verbal Learning Recognition |

| Delis Kaplan Executive Function System (D-KEFS) |

| Trail Making Test |

| Verbal Fluency Test |

| Design Fluency Test |

| Behaviour Rating Inventory of Executive Function, Parent Form (BRIEF) |

| Child Health Questionnaire, Parent Form (CHQ-PF28) |

Data analysis

All analyses used SAS_ Version 9.1 (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC); significance was defined as p<0.05. Subjects found to be GHD by the aforementioned criteria were compared to non-GHD subjects with respect to a number of factors. Given small sample sizes, continuous factors were compared between the two groups via exact p-values from the Mann- Whitney test and categorical outcomes via Fisher’s exact test.

Results

Among the families of patients from the TBI clinic who were invited to enrol in the study, 32/52 (62%) elected to participate. Enrollees were not different from those who declined to participate in the following characteristics: proportion male, age at injury, age at prospective enrolment or GCS (Table II).

Table II.

Characteristics of enrollees vs refusals.

| Enrollees | Non-enrollees | p-value* | |

|---|---|---|---|

| n | 32 | 20 | |

| # males (%) | 20 (63) | 10 (50) | 0.4027 |

| Age at injury (Mean (SD)) | 12.7 (5.3) | 13.1 (4.7) | 0.9627 |

| Age at recruitment (Mean (SD)) | 15.7 (3.7) | 15.6 (3.6) | 0.8691 |

| GCS (Median (Range)) | 5 (3–15) | 3 (3–9) | 0.3626 |

Comparing the two groups: Fisher’s exact test for gender, Mann-Whitney test for others.

Of the 32 subjects, 29 were able to participate in neuropsychological testing. The other three participants were unable to participate in neuropsychological testing due to limitations in communication and psychomotor skills. The guardians of these three subjects participated in the Vineland-II Interview, which provided a measure of personal and social skills of the subject. Descriptors of the 29 subjects who participated in neuropsychological testing are presented in Table III.

Table III.

Descriptive characteristics of subjects who participated in neuropsychological testing.

| n | 29 |

|---|---|

| Categorical variables: Frequency (%) | |

| Male | 18 (62) |

| Tanner stage 3–5 | 25 (86.2) |

| Severity of injury | 8 moderate, 21 severe |

| Continuous variables* | |

| Age at injury (years) | 12.6 (5.5) |

| Age at testing (years) | 15.3 (3.6) |

| Initial GCS (Median (Range)) | 5 (3–15) |

| BMI z-score at overnight testing | 0.7 (1.2) |

Unless otherwise noted, reported as mean (SD).

Growth hormone

Among subjects who participated in neuropsychological assessment, 5/29 subjects (17%) failed to have an overnight GH level above 5 ngmL_1 and 9/27 (33%) did not increase GH levels above 7ngmL_1 (subjects <18 years) or 5 ngmL_1 (subjects _18 years) in response to provocative stimuli. Provocative testing was not completed for 2/29 subjects. One subject did not undergo provocative testing due to elevated blood pressure at the time of admission and the other subject did not undergo provocative testing due to intravenous line failure. Four out of 29 subjects (14%) failed both testing modalities and 34% of subjects (10/29) exhibited insufficient GH secretion during one of the two tests.

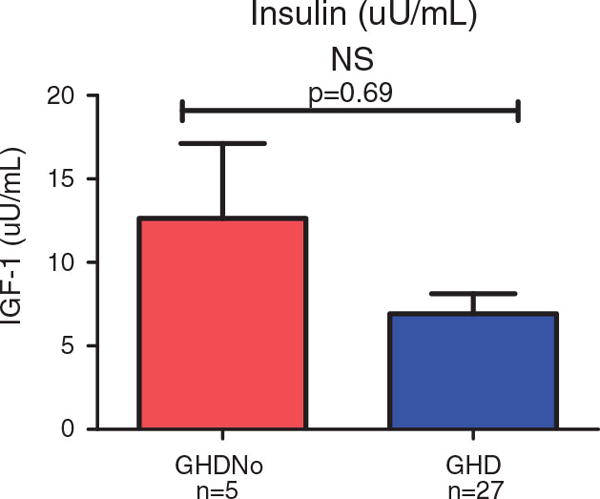

Insulin

Statistical analysis of the insulin production (after overnight testing, but before stimulation testing) between groups was not statistically significant.

Neuropsychological tests

Subjects who were GHD on overnight testing were compared to subjects who were GHD on stimulation testing on a variety of neuropsychological and quality-of-life measures (Tables IV and V).

Table IV.

Subject Characteristics by GHD Classification*

| GHD by Stimulation Comparison

|

GHD by Overnight Comparison

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Not GHD | GHD | p-value** | Not GHD | GHD | p-value** | |

| n | 18 | 9 | – | 24 | 5 | – |

| Categorical Variables | ||||||

| Male | 10 (56) | 7 (78) | 0.41 | 14 (58) | 4 (80) | 0.62 |

| Tanner stage 3–5 | 16 (89) | 7 (78) | 0.58 | 20 (83) | 5 (100) | 1.00 |

| Severe brain injury | 6 (33) | 1 (11) | 0.36 | 16 (67) | 5 (100) | 0.28 |

| Continuous Variables | ||||||

| Age at testing (years) | 15 | 17 | 0.81 | 15 | 18 | 0.03 |

| Age at injury (years) | 13 | 15 | 0.71 | 13 | 18 | 0.01 |

| GCS | 6 | 3 | 0.10 | 6 | 3 | 0.16 |

Frequency (percent) reported for categorical variables; medians reported for continuous variables

Comparing the two groups: Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables, Mann-Whitney test (exact p-value) for continuous variables

Table V.

Neuropsychological Outcome Medians by GHD Classification

| GHD by Stimulation Comparison

|

GHD by Overnight Comparison

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Not GHD | GHD | p-value* | Not GHD | GHD | p-value* | |

| n | 18 | 9 | – | 24 | 5 | – |

| Verbal IQ | 81.5 | 89 | 0.24 | 87 | 82 | 0.42 |

| Performance IQ | 97 | 99 | 0.68 | 97 | 98 | 0.90 |

| Full Scale IQ | 86 | 93 | 0.43 | 88 | 88 | 0.51 |

| Verbal Memory | 92.5 | 91 | 0.45 | 93 | 91 | 0.25 |

| Visual Memory | 86.5 | 73 | 0.34 | 88 | 60 | 0.03 |

| Attention Concentration | 88 | 79 | 0.28 | 85 | 73 | 0.20 |

| General Memory Index | 89 | 77 | 0.08 | 89 | 73 | 0.01 |

| Trails Composite | 7 | 4 | 0.38 | 8 | 1 | 0.11 |

| Verbal Fluency 1 | 7.5 | 7 | 0.37 | 8 | 5 | 0.17 |

| Verbal Fluency 2 | 9 | 9 | 0.60 | 10 | 5 | 0.07 |

| Verbal Fluency 3 | 8 | 6 | 0.38 | 8 | 5 | 0.12 |

| Verbal Fluency 3b | 9 | 8 | 0.45 | 9 | 6 | 0.14 |

| Design Composite | 10 | 8 | 0.21 | 10 | 8 | 0.24 |

| Letter Number Sequencing | 8.5 | 8 | 0.93 | 9 | 8 | 0.21 |

| Coding | 7 | 5 | 0.83 | 7 | 5 | 0.28 |

| Global Health | 60 | 85 | 0.61 | 85 | 60 | 0.07 |

| Physical Functioning | 100 | 66.67 | 0.31 | 100 | 56 | 0.01 |

| Emotional/Behavioral Limitations | 100 | 100 | 0.73 | 100 | 100 | 1.00 |

| Physical Limitations | 100 | 100 | 1.00 | 100 | 67 | 0.28 |

| Bodily Pain/Discomfort | 60 | 80 | 0.34 | 60 | 80 | 0.81 |

| Behavior | 58.75 | 58.75 | 0.91 | 59 | 59 | 0.75 |

| Global Behavior Item | 72.5 | 85 | 0.41 | 85 | 60 | 0.40 |

| Mental Health | 58.33 | 75 | 0.59 | 58 | 75 | 0.42 |

| Self Esteem | 66.67 | 75 | 0.84 | 67 | 58 | 0.71 |

| General Health Perceptions | 49.38 | 46.25 | 0.48 | 49 | 21 | 0.01 |

| Change in Health | 50 | 37.5 | 0.50 | 50 | 0 | 0.08 |

| Parental Impact – Emotional | 75 | 66.67 | 0.60 | 83 | 33 | 0.10 |

| Parental Impact – Time | 50 | 62.5 | 0.49 | 56 | 50 | 0.46 |

| Family Cohesion | 72.5 | 60 | 0.82 | 85 | 60 | 0.86 |

| Behavioral Regulation Index | 68 | 56.5 | 0.13 | 62 | 52 | 0.39 |

| Metacognition Index | 61 | 66 | 0.32 | 62 | 66 | 0.13 |

| Global Executive Composite | 62 | 62.5 | 0.85 | 62 | 63 | 0.53 |

Exact p-value from the Mann-Whitney test

Neuropsychological associations of GHD on overnight testing

Subjects who were GHD on overnight testing had statistically significantly lower scores on a selected measure of visual memory (Not GHD¼88, GHD¼60, p¼0.03) and health-related qualityof-life, specifically Physical Functioning (Not GHD¼100, GHD¼56, p¼0.01) and General Health Perceptions (Not GHD¼49, GHD¼21, p¼0.01). The neuropsychological effects of GHD on overnight testing were unrelated to either the severity of the brain injury or differences in IQ (p>0.05).

Neuropsychological associations of GHD on provocative testing

When analyses were based solely on those who were GHD on provocative testing compared to those who were not GHD on provocative testing, no significant neurocognitive or quality-of-life differences were found.

Discussion

Traumatic brain injury is a serious cause of morbidity and mortality in children and adolescents and is increasingly recognized as a cause of pituitary dysfunction in this population. The findings on some neuropsychological tests, particularly memory tests, suggest that deficient levels of GH on overnight testing are negatively associated with some aspects of neuropsychological functioning. Similar effects on neurocognition and QoL have been found in adults who are GHD [4, 16–18]. A simple explanation would be that those who are GHD also sustained more serious injuries and therefore have lower IQs in addition to other neurocognitive deficits. However, these findings cannot be explained by severity of injury or IQ (p>0.05). Growth hormone deficiency has been associated with poor memory performance [40]. The results suggest that there is a more focused association with visual processing memory and memory requiring a visual component. This finding stands in contrast to those of other investigators and raises important questions as to how the two may be related and what occurred during this investigation to result in this specific association. Although standardized testing was used and a well-disciplined format of examination was followed, the possibility of examination artifact must be considered, either in the process or with the instruments used. The possibility of discovering a specific and targeted effect of neuroendocrine factors that influence results must be considered and serve as the basis for further investigation. There are a growing number of reports on the role of insulin in memory, especially for those with Alzheimer’s Disease [41]. It has been reported that GH receptors in the hippocampus become insulin resistant and therefore lose their influence on hippocampal functioning [42]. The subjects with higher BMIs may have been pre-diabetic or frank diabetes (Type II) and possible indirect effects of poor insulin production may have occurred. Although statistical analysis of the insulin production between groups was not significant (see Figure 1), the complexity of neuropsychological functioning and brain/neuroendocrine relationship is complex and results increase observational powers but leave additional questions and avenues to pursue.

Figure 1.

Additional possible explanations for these findings may lie in the binding sites for GH. In both human and rat models, specific binding sites for GH include the choroid plexus, hippocampus, hypothalamus and spinal cord [3]. In addition to new learning and short-term memory, these areas are also involved in emotional expression and emotional learning. Functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) studies have been conducted to better understand the areas of the brain affected by GHD and GH substitution. Arwert et al. [43] used brain fMRI to investigate the effects of GH substitution therapy on cognitive function in adult patients with GHD. This study found statistically significant differences between the GH-treated and control group in performance on a measure of long-term memory. fMRI showed more brain activation in the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex and ventrolateral prefrontal cortex, as well as in the anterior cingulate, parietal, occipital and motor cortices and right thalamus. Decreased activation was shown in the ventrolateral prefrontal cortex after GH treatment as compared to placebo treatment, indicating decreased effort and more efficiency while completing the task. The criteria for diagnosing GHD in this study population may provide a more conservative estimate of GHD than any prior reports of patients following TBI, given that prior reports used stimulation testing as the sole means of diagnosis of GHD [4, 44–46]. Although the use of stimulation testing to diagnose GHD remains widely employed, this form of testing has inspired much controversy due to poor overall sensitivity and specificity [47–49].

Critics of GH stimulation testing have noted that the cut-off for GHD has risen from 3 to 7 to 10 ngmL_1 as recombinant human GH has become more widely available. Many children who continue to grow normally may fail to release GH in response to stimulation testing, while others will exhibit inconsistent responses when tested on separate occasions. Additionally, some children with clinical pictures of GHD occasionally have stimulated GH values above these cut-offs [49]. The ongoing debate about GH stimulation testing and cut-off levels reinforces the idea that GHD likely exists as a spectrum and that test results must be correlated with clinical information [50]. As the results indicate, this debate may have neurocognitive and quality-of-life implications that should be considered in children and adolescents following brain injury and potential GHD. Based on this study, the question of whether stimulation testing is enough to rule out neurocognitive deficits due to GHD must be asked. Although this study is limited by a small sample size, the neuropsychological differences produced by overnight testing compared to stimulation testing should be further explored. This study and replication of findings similar to those seen in adults with moderate-to-severe TBI raises the question of possible growth hormone replacement as a therapeutic intervention. More specifically, these findings open the door to consider the possibility that neurocognitive deficits following moderate-tosevere TBI may have, in part, a neuroendocrine solution, in addition to current instructional and medication interventions [51].

The literature has shown a relationship between cognitive functioning and growth hormone levels in adults. The relationship with younger subjects is less well defined and understood. Consequently, all subjects (n¼32) were administered a neuropsychological battery of tests that were sufficiently broad to sample a variety of skills, yet maintained a focus on memory and learning. Index scores were used for primary analysis while secondary analysis explored the relationships between sub-test scores and growth hormone status.

The very large number of outcomes examined does increase the likelihood of at least one Type 1 error. While there are ways to adjust for the multiple comparisons, this was not done due to the exploratory nature of the study. Given the multiple significant results were limited to only those comparisons when GHD was defined by overnight testing, further studies of this nature are needed. The results suggest that this should be further explored with a larger sample size.

Despite a small sample size and controversy over stimulation vs overnight GH testing, this study underscores the importance of considering a neuroendocrine evaluation in patients with moderate-tosevere TBI. A better understanding of the direct neuropsychological impact of GHD may inform a more conscientious effort to better identify affected children and adolescents and provide possible forms of interventions.

Acknowledgments

This study has been supported by the following grants: Peter D. Patrick, PhD: Grant #07-302 of the Commonwealth Neurotrauma Initiative Trust.

Fund, administered by VA Department of Rehabilitative Services and GCRC, NIH Grant #M01RR000847. Mark D. DeBoer, MD, MSc, MCR: NIH Grant #K08HD060739.

Footnotes

Declaration of Interest: There are no additional declarations of interest.

References

- 1.Patrick PD, Patrick ST, Duncan E. Neuropsychological recovery in children and adolescents following traumatic brain injury. In: León-Carrión J, von Wild KRH, Zitnay GA, editors. Brain injury treatment: Theories and practices. New York: Taylor & Francis; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tanaka T, Cohen P, Clayton PE, Laron Z, Hintz RL, Sizonenko PC. Diagnosis and management of growth hormone deficiency in childhood and adolescence – Part 2: Growth hormone treatment in growth hormone deficient children. Growth Hormone & IGF Research. 2002;12:323–341. doi: 10.1016/s1096-6374(02)00045-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nyberg F. Growth hormone in the brain: Characteristics of specific brain targets for the hormone and their functional significance. Frontiers on Neuroendocrinology. 2000;21:330–348. doi: 10.1006/frne.2000.0200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Agha A, Rogers B, Sherlock M, O’Kelly P, Tormey W, Phillips J, Thompson C. Anterior pituitary dysfunction in survivors of traumatic brain injury. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2004;89:4929–4936. doi: 10.1210/jc.2004-0511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schneider M, Schneider HJ, Stalla GK. Anterior pituitary hormone abnormalities following TBI. Journal of Neurotrauma. 2005;22:937–946. doi: 10.1089/neu.2005.22.937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Masel BE. Rehabilitation and hypopituitarism after traumatic brain injury. Growth Hormone and IGF Research. 2004;14:S108–S113. doi: 10.1016/j.ghir.2004.03.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Klose M, Juul A, Poulsgaard L, Kosteljanetz M, Brennum J, Feldt-Rasmussen U. Prevalence and predictive factors of post-traumatic hypopituitarism. Clinical Endocrinology. 2007;67:193–201. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.2007.02860.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Popovic V, Aimaretti G, Casanueva FF, Ghigo E. Hypopituitarism following traumatic brain injury. Growth Hormone and IGF Research. 2005;15:177–184. doi: 10.1016/j.ghir.2005.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rothman MS, Arciniegas DB, Filley CM, Wierman ME. The neuroendocrine effects of traumatic brain injury. Journal of Neuropsychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience. 2007;19:363–372. doi: 10.1176/jnp.2007.19.4.363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Niederland T, Makovi H, Gal V, Andre´ka B, A´braha´m C, Kova´cs J. Abnormalities of pituitary function after traumatic brain injury in children. Journal of Neurotrauma. 2007;24:119–127. doi: 10.1089/neu.2005.369ER. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McDonald A, Lindell M, Dunger DB, Acerini CL. Traumatic brain injury is a rarely reported cause of growth hormone deficiency. Journal of Pediatrics. 2008;152:590–593. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2007.12.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Aimaretti G, Ambrosio MR, Benvenga S, Borretta G, De Marinis L, De Menis E, Di Somma C, Faustini-Fustini M, Grottoli S, Gasco V. Hypopituitarism and growth hormone deficiency (GHD) after traumatic brain injury (TBI) Growth Hormone and IGF Research. 2004;14:S114–S117. doi: 10.1016/j.ghir.2004.03.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Urban RJ, Harris P, Masel B. Anterior hypopituitarism following traumatic brain injury. Brain Injury. 2005;19:349–358. doi: 10.1080/02699050400004807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bondanelli M, de Marinis L, Ambrosio MR, Monesi M, Valle D, Zatelli M, Fusco A, Bianchi A, Farneti M, Degli E. Occurrence of pituitary dysfunction following traumatic brain injury. Journal of Neurotrauma. 2004;21:658–696. doi: 10.1089/0897715041269713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ghigo E, Masel B, Aimaretti G, Le´on-Carrión J, Casanueva F, Dominguez-Morales R, Elovic E, Perrone K, Stalla G, Thompson C. Consensus guidelines on screening for hypopituitarism following traumatic brain injury. Brain Injury. 2005;19:711–724. doi: 10.1080/02699050400025315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Aleman A, de Vries WR, de Haan EHF, Verhaar HJJ, Samson MM, Koppeschaar HPF. Age-sensitive cognitive function, growth hormone and insulin-like growth factor 1 plasma levels in healthy older men. Neuropsychobiology. 2000;41:73–78. doi: 10.1159/000026636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rollero A, Murialdo G, Fonzi S, Garrone S, Gianelli M, Gazzerro E, Barreca A, Polleri A. Relationship between cognitive function, growth hormone and insulin-like growth factor 1 plasma levels in aged subjects. Neuropsychobiology. 1998;38:73–79. doi: 10.1159/000026520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sonntag WE, Ramsey M, Carter CS. Growth hormone and insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1) and their influence on cognitive aging. Ageing Research Reviews. 2005;4:195–212. doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2005.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.León-Carrión J, Leal-Cerro A, Cabezas FM, Atutxa AM, Gomez S, Cordero JM, Moreno AS, Ferran MD, Dominguez-Morales MR. Cognitive deterioration due to GH deficiency in patients with traumatic brain injury: A preliminary report. Brain Injury. 2007;21:871–875. doi: 10.1080/02699050701484849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stojanovic M, Pekic S, Pavlovic D. The effects of growth hormone deficiency following moderate and severe traumatic brain injury on cognitive functions. Endocrine Abstracts. 2008;16:P396. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Falleti MG, Maruff P, Burman P, Harris A. The effects of growth hormone (GH) deficiency and GH replacement on cognitive performance in adults: A meta-analysis of the current literature. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2006;31:681–691. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2006.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Florkowski CM, Joyce SP, Espiner EA, Donald RA. Growth hormone replacement does not improve psychological wellbeing in adult hypopituitarism: A randomized crossover trial. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 1998;23:57–63. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4530(97)00093-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Baum HBA, Katznelson L, Sherman JC, Biller B, Hayden D, Schoenfeld D, Cannistraro K, Klibanski A. Effects of physiological growth hormone (GH) therapy on cognition and quality of life in patients with adult-onset GH deficiency. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 1998;83:3184–3189. doi: 10.1210/jcem.83.9.5112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kreitschmann-Andermahr I, Poll EM, Reineke A, Gilsbach J, Brabant G, Buchfelder M, Faßbender W, Faust M, Kann P, Wallaschofski H. Growth hormone deficient patients after traumatic brain injury – Baseline characteristics and benefits after growth hormone replacement – An analysis of the German KIMS database. Growth Hormone and IGF Research. 2008;18:472–478. doi: 10.1016/j.ghir.2008.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tanner JM. Growth at adolescence. 2nd. London, England: Blackwell Science Ltd; 1978. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Roemmich JN, Clark PA, Weltman A, Veldhuis JD, Rogol AD. Pubertal alterations in growth and body composition: IX. Altered spontaneous secretion and metabolic clearance of growth hormone in overweight youth. Metabolism. 2005;54:1374–1383. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2005.04.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rose SR, Municchi G, Barnes KM, Cutler GB., Jr Overnight growth hormone concentrations are usually normal in pubertal children with idiopathic short stature—a Clinical Research Center study. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 1996;81:1063–1068. doi: 10.1210/jcem.81.3.8772577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Consensus guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of growth hormone (GH) deficiency in childhood and adolescence: summary statement of the GH Research Society. GH Research Society. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2000;85:3990–3993. doi: 10.1210/jcem.85.11.6984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Juul A, Bernasconi S, Clayton PE, Kiess W, DeMuinck-Keizer Schrama S. European audit of current practice in diagnosis and treatment of childhood growth hormone deficiency. Hormone Research. 2002;58:233–241. doi: 10.1159/000066265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wechsler D. Wechsler Abbreviated Scale of Intelligence (WASI) manual. San Antoni, TX: The Psychological Corporation; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wechsler D. WISC-IV technical and interpretive manual. San Antonio, TX: The Psychological Corporation; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wechsler D. WISC-IV administration and scoring manual. San Antonio, TX: The Psychological Corporation; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wechsler D. Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale. 3rd. San Antonio, TX: The Psychological Corporation; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sheslow D, Adams W. Wide Range Assessment of Memory and Learning. 2nd. Wilmington, DE: Wide Range, Inc; 2003. (Administration and Technical Manual). [Google Scholar]

- 35.Delis DC, Kaplan E, Kramer JH. The Delis-Kaplan Executive Function System: Examiner’s Manual. San Antonio, TX: The Psychological Corporation; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Delis DC, Kaplan E, Kramer JH. The Delis-Kaplan Executive Function System: Technical Manual. San Antonio, TX: The Psychological Corporation; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sparrow S, Balla D, Cicchetti DV. The Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scales. 2nd. Circle Pines, MN: American Guidance Service; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Landgraf JM, Abetz L, Ware JE., Jr . Child Health Questionnaire (CHQ): A User’s Manual. Boston, MA: The Health Institute, New England Medical Center; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gioia GA, Isquith PK, Guy SC, Kenworthy L. Behavior Rating Inventory of Executive Function: Professional Manual. Lutz, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources, Inc; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Arwert LI, Veltman DJ, Deijen JB, van Dam PS, Delemarrevan deWall A, Drent ML. Growth hormone deficiency and memory functioning in adults visualized by functional magnetic resonance imaging. Neuroendocrinology. 2005;82:32–40. doi: 10.1159/000090123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Watson GS, Craft S. Modulation of memory by insulin and glucose: Neuropsychological observations in Alzheimer’s disease. European Journal of Pharmacology. 2004;490:97–113. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2004.02.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rasgon NL, Kenna HA, Wroolie TE, Kelley R, Silverman D, Brooks J, Williams KE, Powers BN, Hallmayer J, Reiss A. Insulin resistance and hippocampal volume in women at risk for Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiology of Aging. 2011;32:1942–1948. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2009.12.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Arwert LI, Veltman DJ, Deijen JB, van Dam PS, Drent ML. Effects of growth hormone substitution therapy on cognitive functioning in growth hormone deficient patients: A functional MRI study. Neuroendocrinology. 2006;83:12–19. doi: 10.1159/000093337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Aimaretti G, Ambrosia MR, Di Somma C, Gasperi M, Cannavo S, Scaroni C, Fusco A, Del Monte P, De Menis E, Faustini-Fustini M. Residual pituitary function after brain injury-induced hypopituitarism: A prospective 12-month study. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2005;90:6085–6092. doi: 10.1210/jc.2005-0504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bavisetty S, Bavisetty S, McArthur DL, Dusick JR, Wang C, Cohan P, Boscardin W, Swerdloff R, Levin H, Chang D. Chronic hypopituitarism after traumatic brain injury: Risk assessment and relationship to outcome. Neurosurgery. 2008;62:1080–1093. doi: 10.1227/01.neu.0000325870.60129.6a. discussion 1093–1094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bondanelli M, Ambrosio MR, Cavazzini L, Bertocchi A, Zatelli MC, Carli A, Valle D, Basaglia N, Uberti Anterior pituitary function may predict functional and cognitive outcome in patients with traumatic brain injury undergoing rehabilitation. Journal of Neurotrauma. 2007;24:1687–1697. doi: 10.1089/neu.2007.0343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Badaru A, Wilson DM. Alternatives to growth hormone stimulation testing in children. Trends in Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2004;15:252–258. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2004.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gandrud LM, Wilson DM. Is growth hormone stimulation testing in children still appropriate? Growth Hormone and IGF Research. 2004;14:185–194. doi: 10.1016/j.ghir.2003.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tillmann V, Buckler JM, Kibirige MS, Price DA, Shalet SM, Wales JK, Addison M, Gill M, Whatmore A, Clayton P. Biochemical tests in the diagnosis of childhood growth hormone deficiency. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 1997;82:531–535. doi: 10.1210/jcem.82.2.3750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rosenfeld RG, Albertsson-Wikland K, Cassorla F, Frasier SD, Hasegawa Y, Hintz RL, Lafranchi S, Lippe B, Loriaux L, Melmet S. Diagnostic controversy: The diagnosis of childhood growth hormone deficiency revisited. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1995;80:1532–1540. doi: 10.1210/jcem.80.5.7538145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Patrick PD, Mabry J, Gurka M, Buck M, Goodkin H, Rust R. Use of Donepezil for memory and executive disorders following severe traumatic brain injury in children and adolescents. International NeuroTrauma Letter. 2011;2:25. [Google Scholar]