Abstract

OBJECTIVES:

The objectives of this study were to assess the current situation of the teaching and training of undergraduate and postgraduate programs in family medicine in KSA, assess the current practice of family medicine, and draw a roadmap to achieve Saudi vision 2020.

MATERIALS AND METHODS:

This study was conducted with the support and collaboration of the Primary Health Care Department of the Ministry of Health, Saudi Arabia, and World Health Organization (EMRO) in November 2015. Based on the literature review of previous studies conducted for similar purposes, relevant questionnaires were developed. These consisted of four forms, each of which was directed at a different authority to achieve the above-mentioned objectives. Data of all questionnaires were coded, entered, and analyzed using SPSS version 16.

RESULTS:

There are 2282 primary health-care centers (PHCCs), 60% of which are in rural areas. More than half of the PHCCs have a laboratory and more than one-third have a Radiology Department. Out of the 6107 physicians, 636 are family physicians (10%). All medical colleges have a family medicine department with a total staff of 170 medical teachers. Thirteen departments run family medicine courses of 4–8 weeks' duration for students. Fourteen colleges have internship programs in family medicine and four colleges have postgraduate centers for family medicine (27%). There are 95 training centers for Saudi Board (Saudi Board of Family Medicine [SBFM]) and 68 centers for Saudi Diploma (Saudi Diploma of Family Medicine [SDFM]). The total number of trainers was 241, while the total trainees were 756 in SBFM and 137 in SDFM.

CONCLUSIONS:

This survey showed that there is a shortage of qualified family physicians in all health sectors in Saudi Arabia as a result of the lack of a strategic plan for the training of family physicians. A national strategic plan with specific objectives and an explicit budget are necessary to deal with this shortage and improve the quality of health-care services at PHCCs.

Keywords: Family practice, strategic plan, Saudi Arabia

Introduction

Family medicine (FM) is one of the most important medical specialties in the world as its wide range of health services are meant for all individuals regardless of age, gender, and affected organ or system. It stands on few but important principles, namely comprehensiveness, continuity, coordination, and accessibility.[1] FM was recognized in the USA in 1969 as the 20th medical specialty board.[1] In most Arab countries, FM has developed slowly compared to other clinical medical specialties.[2] In Saudi Arabia (KSA), FM was started in a military hospital in Riyadh in the early 1980s. Later, the postgraduate certificate was given recognition. Fellowship programs in FM were started in King Saud University and King Faisal University[3] followed by Arab Board in (1991). This was followed by the Saudi Board under the umbrella of Saudi Commission for Health Specialties (SCFHS) in 1995. The Saudi Board of Family Medicine (SBFM) consisted of 4 years of structured training covering a broad scope of knowledge and skills.[4] Owing to the need to produce an adequate number of competent family practices (FPs), the Ministry of Health (MOH) and SCFHS launched Saudi Diploma of Family Medicine (SDFM) in 2008 in three provinces. Nowadays, most regions in KSA have either SBFM or SDFM. SDFM started as a 14-month training program and was upgraded to 24 months in 2014.[5]

Some studies from KSA have shown that more attention is required at all levels of FM in order to produce an adequate number of FPs and improve both the academic aspects and the services provided by FM in the country.[6,7,8,9,10,11] A few studies have been conducted to evaluate FM in KSA. However, there is a need for a comprehensive national survey to analyze the current situation in KSA and draw up a strategic plan to achieve the national vision of 2020 in FM.

The main purpose of this survey was to analyze the current situation of FM in Saudi Arabia and suggest some practical solutions for improvement. The specific objectives are to assess the infrastructure of primary health-care centers (PHCCs), assess the current situation of teaching FM in medical schools, assess the current training of postgraduates in FM, and make practical recommendations for the development of FP and training in KSA.

Materials and Methods

This study was conducted by the Department of Primary Health Care (PHC), MOH, Saudi Arabia, in collaboration with the World Health Organization (WHO-EMRO) in November 2015. Relevant questionnaires based on the WHO report issued in 2014[12] were developed. These consisted of four forms, each of which was directed at a different authority to achieve the above-mentioned goals. The first questionnaire comprising many questions on the current practice and training in FM in KSA (political commitment for FM, strategic plan, funding, and support for postgraduate training programs in FM) was administered to the high authorities in MOH. The second form, administered to the directors of PHCC in the 13 regions in KSA, dealt with the issues related to the entire population served, the number of PHCC, physicians and nurses, diagnostic facilities available, clinical guidelines, essential drugs, effective referral system between PHCCs and hospitals, a plan to train family doctors, barriers to the implementation of FP, and the suggested solutions to these issues. The third form, completed by the directors of postgraduate programs of FM, contained the following questions: the number of training centers, the number of trainers and trainees, action plans to train family doctors, funds allocated specifically to training, challenges to training, and suggestions to overcome these problems. The fourth form, administered to the chairmen of FM departments in medical colleges, consisted of questions on the following: Whether there is a department of FM, the total number of staff, courses for undergraduate students, allocation of special rotation for FM during internship, a training center, difficulties in the teaching of FM, and suggested solutions to these issues. After ethical approval was given by the Research Ethical Committee, a written consent was obtained from every participant in this study. The questionnaires were distributed to all the participants by e-mail and collected by the first investigator. Data of all questionnaires were coded, entered, and analyzed using SPSS version 16 (Statistical Package for Social sciences version 16, Chicago, USA, SPSS Inc.). The results of this survey were presented in a 2-day workshop conducted by MOH, Saudi Arabia, and WHO-EMRO in Riyadh city and attended by a total of thirty participants representing different health sectors in Saudi Arabia. The results of the survey were discussed, and the relevant practical recommendations made were reviewed and approved in January 2016.

Results

The participants of this study were three high authorities of the MOH and SCFH, deputy assistants of PHC in all regions, chairmen of family departments of 15 medical colleges, and 18 directors of postgraduate programs of FM in KSA. Twenty-two medical colleges were invited to participate in this survey by e-mail and by personal phone contact with the chairmen of the family and community departments all over KSA. Fifteen colleges responded (68%), representing most of the old and new medical colleges in the country. All colleges have FM departments with a total staff of 170 medical teachers-academics (range 1–56).

All three high-level decision-makers agreed that FP could be used as a model for the improvement of PHC services and received political support. FP is an important part of the national health policy and, is implemented in many health sectors including PHCCs of the MOH. It was revealed that the postgraduate studies in FM (SBFM, SDFM) produced 100–120 family doctors annually. The MOH allocated funds for the running of FP programs, but this was inadequate.

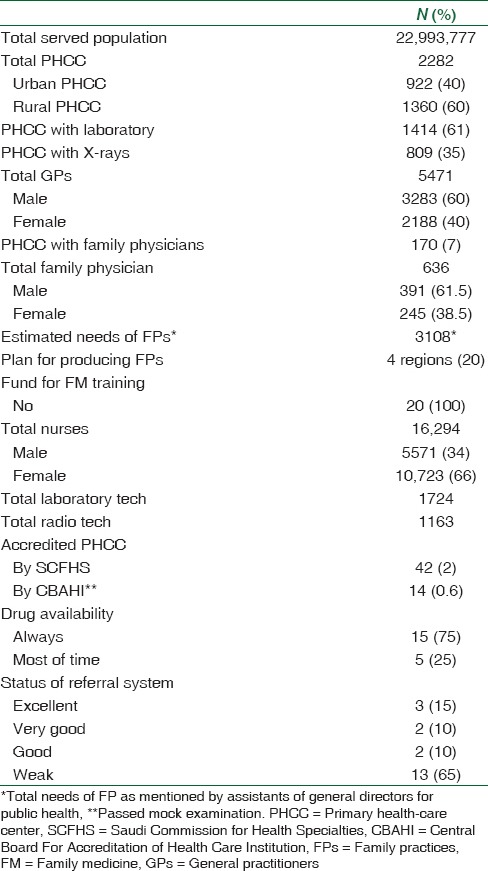

It was mentioned that the PHCC network covered most of population and provided comprehensive care for acute, chronic health problems as well as health promotion services such as health education/immunization and for all citizens. Table 1 shows the profile of PHCCs in KSA. There are 2282 PHCCs, 60% of which are in rural areas all over KSA, and serve about 23,000,000 people. More than half of PHCCs have laboratories (61%) and more than one-third have radiological services (35%). There are 6107 physicians, 636 out of whom are family physicians (10%). Essential drugs are always available in most of PHCCs in 15 directorates (75%) and most of the time in the other five directorates (25%). Referral between PHCCs and hospitals was described by most directorates as weak (65%), very good/good (20%), and excellent (15%).

Table 1.

Profile of primary health-care centers in Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, 2015

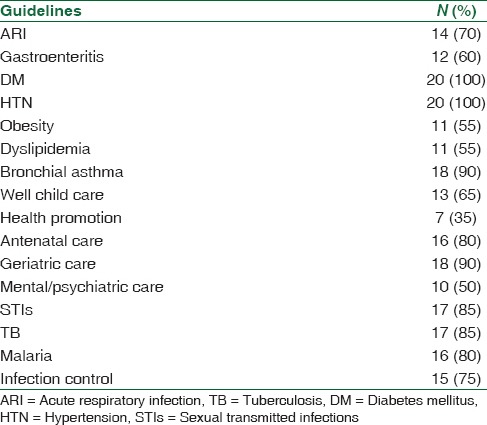

The directorates reported that clinical guidelines were available in their respective PHCCs. Most PHCCs had guidelines on diabetes mellitus, hypertension, asthma, geriatric care, sexually transmitted infections, and TB, but guidelines on obesity, dyslipidemia, Acute Respiratory Infection (ARI), Gastroenteritis (GE), and health promotion were few [Table 2].

Table 2.

Availability of clinical guideline in regions (n=20 directorates)

On continuous professional development of PHCC physicians, 2076/5471 (38%) doctors were trained for 21 days on the seven modules of Family Medicine Essentials in most regions of KSA. Sixteen directorates have continuous professional development programs and on-the-job training for their PHCC doctors.

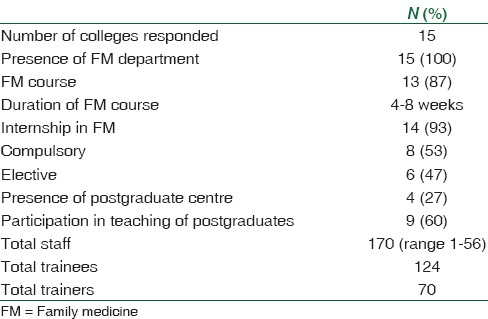

Thirteen departments of the colleges run courses of 4–8 weeks' duration (theory and practical). For students, 14 colleges, have internships in FM for 4 weeks, and in eight colleges (53%) it was compulsory. Only four colleges have postgraduate centers for FM (27%) and 60% participate in the teaching of postgraduate students [Table 3].

Table 3.

Profile of undergraduate education of family medicine and medical colleges, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, 2015

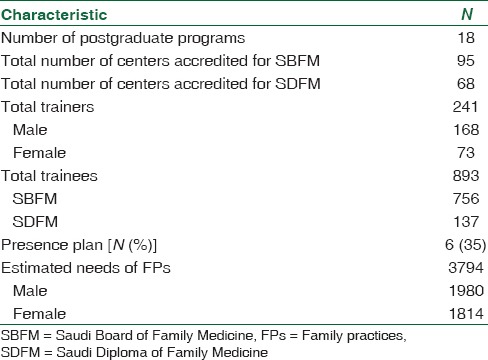

Of the 18 directors of postgraduate program of FM who were included in this survey, 17 responded (94%). There are 95 training centers for SBFM and 68 for SDFB. There are 241 trainers (168 males, 73 females). The total number of SBFM trainees was 756, while SDFM had 137 trainees.

Directors estimated that the total number of family physicians required was about 3800. Only six programs (35%) had written plans for the training of an adequate number of family physicians in their regions or health sectors [Table 4].

Table 4.

Profile of postgraduate education in family medicine, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, 2015

Most directorates reported that they had PHCCs accredited for postgraduate studies (SBFM or SDFM). There are at present 42 accredited centers, for training, with a capacity of 329 trainees and 97 trainers. On the regional level, only four directorates had plans to train family physicians and only one directorate had a budget for postgraduate studies in FM. In total, the current estimated requirement of family physicians for all regions is about 3108 doctors.

Discussion

The aim of this study was to assess the current practice of FM in Saudi Arabia and suggest some practical directions for a roadmap toward the achievement of the National Vision 2020 with regard to practice and training in FM in KSA.

There are 2282 PHCCs in Saudi Arabia, to provide preventive and curative services for 23,000,000 people. About 60% of these PHCCs are located in rural areas and villages.

This huge number of PHCCs is an indication of the effort being made by the MOH to make PHCC accessible to most residents in KSA. However, 40% and 65% of PHCCs have no laboratories and X- ray services. This situation is better than what was reported in Reported in 2006 (42% and 67%, respectively).[13]

Since providing each PHCC with X-ray and laboratory services is not cost-effective, particularly for the less populated areas, it has been suggested that diagnostic facilities should be made available at nearby hospitals to provide immediate access as accessible by PHCC's physicians and eliminate the need to refer patients to specialists in hospitals. The alternative is to provide referring PHCCs with all diagnostic facilities.

The total number of physicians working at all PHCCs was 6107 compared to 5127 doctors in 2006.[13] Despite this increase, the doctor–people ratio is still low (3, 1/10,000 population) as was reported in 2015.[14]

The other important finding in this study was the shortage of qualified family physicians. The 636 physicians constitute about 10% of the total number of PHCC physicians covering only 7% of PHCCs. This figure of FPs is higher than that reported by Osman et al. in 2011[2] in all Arab countries..

The reasons for this shortage are several and include but not limited to the small number of postgraduate training centers in MOH (42 PHCC) and the restricted number of training positions because of the inadequate number of trainers in FM at these training centers as reported in the previous study.[8]

To resolve this major impediment to the implementation of FP in KSA, provision should be made by the establishment for the training of an adequate number of family physicians, and the accreditation of more PHCC centers (at least 100 PHCCs) sought. More family physicians should be recruited to conduct the training.

The family physicians recruited could be given a variety of incentives to encourage them in their work as trainers. Most medical colleges in KSA have FM departments where theoretical and clinical courses are given and internships for FM specialty done.

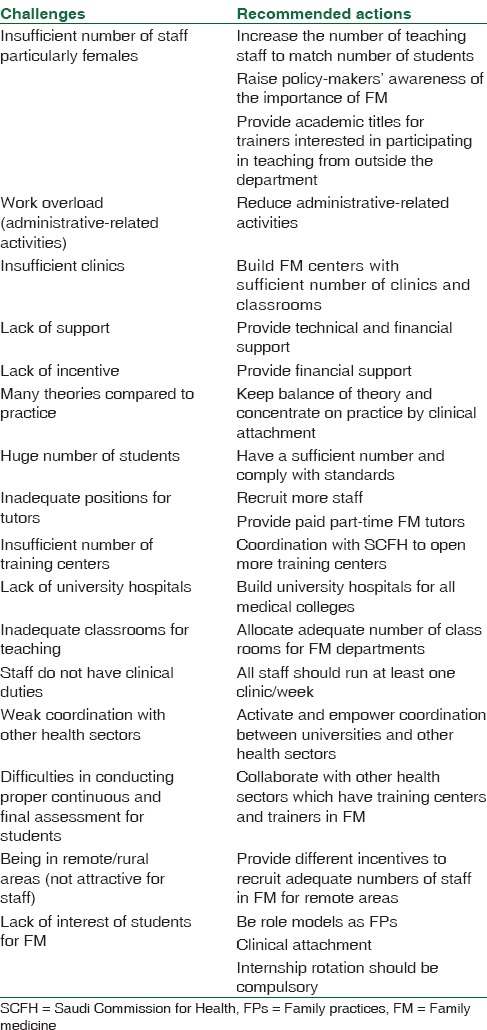

These findings are considered good indicators of the importance of FM in the country. However, there are many challenges to the quality of clinical teaching of FP [Table 5]. Some of these challenges are the lack of training centers affiliated to medical colleges and the shortage of academic staff, and urgent action should be taken to overcome these hurdles; first and foremost is the recruitment of adequate number of staff and second is the establishment of training centers or the identification of some clinics for clinical teaching during FM courses. It is crucial to ensure coordination with other health sectors such as the MOH as regards the utilization their accredited PHCCs at the regional level in the short term to offset the shortage of training centers in medical colleges.

Table 5.

Challenges to undergraduate teaching and recommended actions in family medicine in Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, 2015

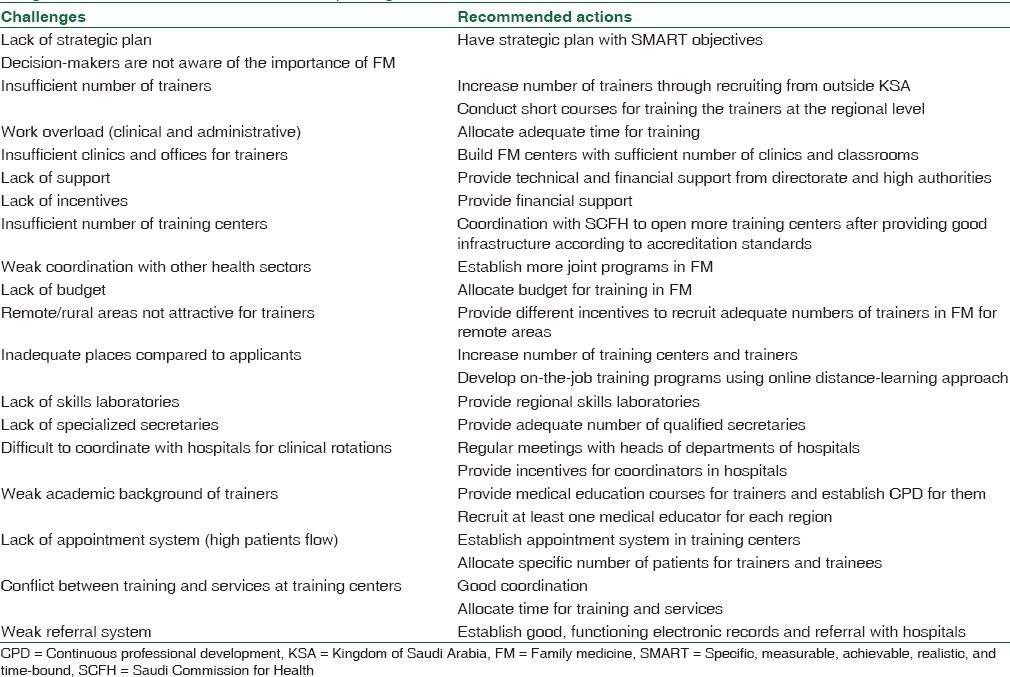

Postgraduate training in FM started in the early 1980s. At the moment, there are 18 postgraduate programs and more than 100 training centers for SBFM and SDFM with 893 trainees and 241 qualified trainers.

These figures are higher than those reported in two previous studies.[8,10] The changes indicate the strenuous efforts made by the concerned authorities to produce more family physicians to make up the shortfall between the present numbers and the national requirement. There are still major issues in postgraduate training in FM.[6] To deal with these challenges, participants suggested many solutions [Table 6], most of which pertain to having a national strategic plan with coherent specific objectives and an adequate budget.

Table 6.

Challenges to postgraduate training and recommended solutions to family medicine in (Postgraduate Program/Directorates of Health Affairs), Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, 2015

At a regional level, general directorates of health affairs should play a major role by setting up more well-equipped training centers, provide incentives for trainers, and forge good relationships with academic institutions. Another important issue in FP at the regional level is the coordination between PHCC and hospitals to deliver high-quality health services for customers.

The participants discussed the results of this study and agreed on the proposed strategic directions and relevant interventions to upgrade FP and FM training as part of the national strategic plan for FM in KSA. They include the following six directions with specific deadlines for the accomplishment of the specific objectives [Appendix 1]: (i) Strengthening governance/regulations and system absorption capacity for FP program, (ii) upgrading of the FP program, (iii) transformation/restructuring of FM training program, (iv) financing of FP program, (v) improvement of quality and safety/standards/accreditation process at all levels of service delivery, (vi) enhancement of community empowerment (demand, marketing, and participation).

Conclusions

This survey showed that there is a shortage of qualified family physicians in all health sectors in Saudi Arabia. Based on the results of this survey, a national strategic plan with specific objectives was discussed and outlined by national expert participants. This plan could be adopted by decision-makers at a high level and at regional levels as a roadmap to upgrade FP in Saudi Arabia.

Financial support and sponsorship

We greatly appreciate WHO-EMRO for their financial and technical support for the conduct of this study.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgment

The authors would like to express their deep appreciation to all participants of the workshop to formulate the final recommendations, and to all respondents from different health sectors in KSA.

Appendix

Appendix 1: Proposed strategic directions and relevant interventions to scale up family practice and family medicine training in KSA (Six strategic directions and 36 interventions during the coming 5 years)

-

Strengthening governance/regulations and system absorption capacity for family practice program

-

Lobby policy-makers in Health Services Council to strengthen family practice as a national health goal for service delivery and move toward universal health coverage with the following actions: (2016)

- Incorporate family practice as an overarching strategy for service provision in the national health policy and plan

- Project future needs for family physicians as endorsed by the Government of KSA

- Establish/strengthen a national high-level multisectional commission for UHC that sets goals, develops roadmaps, and oversees progress in scaling up family practice

- Define gaps on elements of family practice and identify actions to upgrade a comprehensive family practice program in KSA

- Review/update laws and regulations for supporting implementation and expansion of family practice program (2016-2017)

- Establish at least one referral family practice center per year in each governorate or big city which are run by family practices (2016-2018)

- Establish standards for the regulation of family practice program whether implemented through public or private sectors (2016-2017)

-

-

Scaling up implementation of family practice program

- Develop health information and reporting system to monitor health facility (risk factors, health status, system) performance (2016)

- Develop and pilot prototype of a well-functioning referral system between primary, secondary, and tertiary level including feedback and follow-up (includes policies and procedures, instruments, and staff training) (2017-2020)

- Establish public-private partnership through contracting out mechanism with defined catchment population and defined package of services (2017-2020)

-

Transformation/restructuring of family medicine training program (responsibility of Supreme Council for Medical Specialties)

- Advocate with Supreme Council for Medical Specialties to establish, strengthen, and expand family medicine departments and increase the intake of family medicine trainees (at least one family medicine training center/department in each big city or governorate and establish at least one family medicine training centers in all medical colleges) (2016-2020)

- Produce five trainers at the universities and family medicine departments (at least two trainers per center/department) (2016-2020)

- Dedicate adequate budget for postgraduate studies in family medicine (2016)

- Develop and implement competency courses to orient General Practitioners (GPs), nurses, and allied Health workers(HW) on principles and elements of family practice (2016-2018)

- Introduce incentives for physicians enrolled in postgraduate family medicine programs based on work experience in primary health-care services (2016-2018)

- Develop continuous and well-structured professional development (CPD) programs to cover all GPs (2016)

- Standardize curriculum, evaluation, and standards of family medicine board certified programs in KSA (2016-2018)

-

Financing of family practice program (strategic purchasing)

- Introduce family practice financing as integral part of the national health financing strategy in a manner to ensure sufficient and sustainable funding for implementing and expanding family practice in KSA (2016-2017)

- Engage in strategic purchasing for family practice from public and private providers (2016-2020)

- Design and cost essential health services packages to be implemented through family practice and identify target population to be covered (2016-2017)

- Agree on implementation modalities of essential health services package delivered by public, not-for-profit, or for-profit private health-care providers (2016-2017)

- Build capacity to undertake contracting for family practice including outsourcing of services provision (2016-2020)

-

Decide and pilot provider payment modalities, e.g., capitation, case payment, and necessary performance-based payment or their combinations (2016-2017)Note: Health Insurance companies/organizations should be engaged in strategic purchasing for public and private sectors.

-

Improve quality and safety/standards/accreditation process at all levels of service delivery

- Adopt World Health Organization tool for assessing service delivery at primary health-care level (structure, process, and outcomes) and institutionalize it in all primary health-care facilities (2016-2017)

- Develop training and continuous professional development programs for primary health-care health workers on improving the quality of service delivery (2016-2020)

- Strengthen supervision and monitoring functions including interventions to improve the quality of care (2016-2017)

- Introduce/institutionalize accreditation programs to support the performance of the four primary health-care facilities (2016-2020)

- Strengthen referral and electronic family folders (2016-2017)

- Enforcing accreditation of primary health-care facilities (2016-2020).

-

Enhance community empowerment (demand, marketing, and participation)

- Establish a community health board to oversee the establishment of family practice program in each district (2016-2018)

- Launch community campaign to encourage the population to register with reformed health facilities in the catchment area (2016-2018)

- Scale up home health care as an integral part of the family practice approach (2017-2020)

- Establish training on communication skills for staff of health facilities (2016-2018)

- Develop multimedia educational campaigns (2017-2020).

References

- 1.Rakel RE. Essential Family Medicine Fundamentals and Case Studies. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, USA: Saunder Publisher; 2006. pp. 19–27. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Osman H, Romani M, Hlais S. Family medicine in Arab countries. Fam Med. 2011;43:37–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Albar AA. Twenty years of family medicine education in Saudi Arabia. East Mediterr Health J. 1999;5:589–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Saudi Commission for Health Specialties. Saudi board of family medicine. Scientific committee. Saudi Board Family Medicine Curriculum. Saudi Commission for Health Specialties. 2016:16. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Saudi Commission for Health Specialties. Saudi diploma of family medicine. Scientific committee. Saudi Diploma Family Medicine Curriculum. Saudi Commission for Health Specialties. 2015:15. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Birrer RB, Al-Enazy H, Sarru E. Family medicine in Saudi Arabia – Next step. J Community Med Health Educ. 2014;S2:2–5. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Al-Khathami AD. Evaluation of Saudi family medicine training program: The application of CIPP evaluation format. Med Teach. 2012;34(Suppl 1):S81–9. doi: 10.3109/0142159X.2012.656752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Al-Khaldi YM, Al Dawood KM, Al Bar AA, Al-Shmmari SA, Al-Ateeq MA, Al-Meqbel TI, et al. Challenges facing postgraduate training in family medicine in Saudi Arabia: Patterns and solutions. J Health Spec. 2014;2:61–7. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Alshareef MH. Satisfaction of family physicians during their training program, Jeddah, Saudi Arabia. Int J Med Sci Public Health. 2014;3:649–59. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bin Abdulrahman KA, Al Dakheel A. Family medicine residency program in Kingdom of Saudi Arabia: Residents opinion. Pak J Med Sci. 2006;22:250–57. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Al-Khaldi YM, Al Dawood KM, Al Khudeer BK, Al Saqqaf AA. Satisfaction of trainees of Saudi Diploma Family Medicine, Saudi Arabia. Educ Prim Care. 2016;27:421–3. doi: 10.1080/14739879.2016.1219619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.WHO-EM/PHC/165/E. Report on the Regional Consultation on Strengthening Service Provision Through the Family Practice Approach. Cairo, Egypt: 2014. pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, Ministry of Health. Statistical Report. Riyadh. 2006:117. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, Ministry of Health. Statistical Report. Riyadh. 2015:37–9. [Google Scholar]