Abstract

BACKGROUND:

The concept of detection and management of diabetes mellitus at primary health-care centers is justified and widely practised in Saudi Arabia. The objective of this study was to assess the efficacy of diabetic educational programs for noninsulin-dependent (type 2) diabetes mellitus patients, and to determine the predictors of compliance.

MATERIALS AND METHODS:

A longitudinal experimental research design was adopted for this study and conducted at the diabetic outpatient clinic of King Fahd Hospital of the University, Al Khobar, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. A convenient sample of 150 adult patients diagnosed as type 2 diabetes was included in this study.

RESULTS:

There was a significant reduction in the body mass index (BMI) of patients, an improvement in regular self-checks of blood sugar, dietary regimen, foot care, and exercise and lifestyle behavior following the educational program. It was observed that patients' knowledge of diabetes had improved after exposure to the educational program in the three-time intervals.

CONCLUSIONS:

Type 2 diabetes mellitus exhibited significant change in both BMI, sugar accumulation, and adherence to medication after attending the educational program, and there was evidence of improved knowledge of regular self-checks of blood sugar, dietary regimen, foot care, exercise, and lifestyle behavior.

Keywords: Compliance, noninsulin-dependent diabetic mellitus, predictors, University of Dammam

Introduction

Type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) is a disease that is rapidly increasing; 90% of all diabetes presentations are considered type 2 diabetes (T2D). The number of persons affected is expected to rise, reaching 552 million people worldwide with a comparable rise in complications, and healthcare costs.[1] In the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, diabetes has emerged as a major public health problem that has reached epidemic proportions.[2] Crude prevalence of diabetes has been documented as 23.7%, accounting for 37.8% of Saudis aged between 30 and 70 years.[3] By 2035, there could be 7.5 million individuals with T2D in Saudi Arabia. In 2014, 15.7% of the Ministry of Health budget was for direct expenditure on type 1, type 2, and gestational diabetes. It is estimated that around SAR 3.9 billion is spent on suboptimal T2D therapy compliance and persistence. The inaction to tackle this problem at a time when prevalence is on the increase and challenges to optimal T2D management in the public health-care system are considerable, will inevitably result in an escalation of costs.[4]

Various recommendations have been made by the American Diabetes Association (ADA) with regard to the medical nutrition regimen of diabetes; these underscore the importance of reducing diabetic complications.[5] The care of diabetes involves some changes in lifestyle, including dietary habits and regular intake of medications. Successful management of the disease relies on patients' self-care. Compliance is a key element that affects all aspects of health care.[6] The degree of patients' compliance (adherence) to self-care is the extent to which patients carry out the set of daily activities recommended by a health-care professional as a means of managing their diabetes. These include dietary style, exercise, taking medication, monitoring of blood glucose, foot care, as well as the timing, and integration of all of these activities.[7]

A blood glucose control goal requires the active participation of the patient to master a complex array of self-management skills. These include modifying dietary choices, implementing exercise regimes, monitoring blood glucose, and adhering to often complex medication regimens. “Adherence means the extent to which a person's behavior in taking medication and/or executing lifestyle changes corresponds with agreed recommendations from a health care provider”. However, nonadherence to medication is particularly common among patients with T2D.[8]

Compliance in healthcare is defined as the extent to which a patient's behavior (in terms of taking medication, executing the lifestyle changes[9] is in consonance with recommendation. One component of self-care is adherence to often complicated medication regimes. Good adherence is associated with reduced risk of diabetes complications, reduced mortality, and reduced economic burden. Adherence to a nutrition regimen requires that the patient takes on board specific nutrition recommendations such as making alterations to the previous nutrition patterns, implementing new nutrition behaviors, evaluating the impact of those behaviors on glycemic control, and participating in an exercise program.[10]

Exercise is a method of controlling T2DM by stabilizing the plasma glucose in the acute phase and facilitates improvements in body structure. Exercise has undoubted advantages for these patients, as it enhances glycemic control, reduces cardiovascular disease risk, and body weight. Evidence has shown that T2DM can be prevented by doing ½ h of moderate-intensity activity 5 days a week.[11]

Many studies have indicated that education programs for patients with diabetes mellitus (DM) have produced significant benefits in glycemic control. The evidence suggests that participation in a multifactorial health education program on diabetes, significantly improved glycemic and lipid levels in the short-term, particularly among participants with extremely adverse A1C or low-density lipoprotein levels before participation. Particularly among participants with extremely adverse glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) or low-density lipoprotein levels, it was found that 6 months of an educational program for DM patients helped them to gain better glycemic control.[12] The objective of the present study was to evaluate the efficacy of diabetic educational program for noninsulin-dependent (type 2) diabetic patients.

Materials and Methods

A longitudinal experimental research design was used. A convenient sample of 150 adult patients diagnosed as type-2 diabetes was drawn from diabetic outpatient clinics of King Fahad University Hospital. Randomization is beneficial because on average it tends to evenly distribute both known and unknown confounding variables between the intervention and control group. However, when the sample size is small, randomization may not adequately accomplish this balance. Thus, alternative design and analytical methods are often used in place of randomization when only small sample sizes are available. Hence, there was no control group in this study.

The research was conducted between March 2014 and December 2015. For the duration of the study, all patients visiting the outpatient diabetic clinic at King Fahd Hospital of the University (KFHU), who were referred from their endocrinology clinic (outside of KFHU) and diagnosed as type-2 diabetes, were eligible for inclusion in this study. Inclusive criteria: The following criteria were set by the researchers for inclusion of subjects in this study: (a) Patients >18 years with T2D; (b) first visit to the diabetic outpatient clinic at KFHU and; (c) fasting blood sugar of more than 130 mg/dl. The ADA advises that individual blood sugar levels before meals be kept between 80 and 130 mg/dl, and at 1–2 h after meals under 180.[13] Patients with diabetic retinopathy, nephropathy, neuropathy, and diabetic foot wound were excluded from the study.

Tool I: Structured questionnaire consisted of two parts: Part 1- covered patient demographic data and general information. Section One: related to age, gender, occupation, level of education, marital status, and family history of disease. Section Two: related to smoking, physical activities, duration, and consistency. Section Three: included health-related behaviors (skin and eye). Section Four: related to diabetes education. Part 2 - medical records related to the measurement of fasting blood sugar level and A1C test.

Tool II: calorie measurement and dietary assessment: This tool assessed dietary compliance and other areas of focus during dietary guidance and measurement of calories.

Tool III: performance checklist was used to record such measurements as body mass index (BMI).

Before start of the study, a research proposal and the tools for data collection were reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Imam Abdulrahman Bin Faisal University. Permission was obtained from responsible authorities in the diabetes clinic at KFHU. A consent form was signed by patients who were to participate in the study. Confidentiality and anonymity of individual response were guaranteed.

Tools of this study were developed by the researchers after a review of related literature. A Pilot study was carried out on five diabetic patients to test feasibility and applicability of the tool and necessary modifications made accordingly.

The procedure was covered in three phases: Phase I was an assessment that included base line assessment of patient compliance using a structured questionnaire, dietary history questionnaire, and performance checklist. Phase II was the implementation of an educational program given individually to the patients. Each patient was interviewed five times by the researcher during the study for 30 min per session. The educational program mainly focused on: understanding diabetes, risk factors control, cessation of smoking, nutritional and energy balance, carbohydrate awareness, glycemic index, insulin injection, and adjusting insulin dose after hypoglycemia and hyperglycemia, self-monitoring of blood glucose, benefits of physical activity and lifestyle changes. At the end of the educational program, a handy pocket book and a compact disk on the contents of the educational program was distributed to the patients. Phase III was follow-up and follow-up assessment carried out three times using tools II and III namely, (i) before the implementing the health education program, (ii) 3 months after the implementation of the health education program, and (iii) 6 months after the implementation of the health education program.

Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS, IBM, Chicago, Illinois, USA) version 19 was used for the analysis. Continuous data were presented as mean and standard deviation and categorical data as number and percentage using cross tabulation. A Cochran test was performed to test the probability of significant differences/changes on patients' compliance and behaviors before enrolling in the educational program, at 3 and 6 months following the educational intervention. Post hoc comparisons (McNemar tests) were conducted to test for possible significant changes over two-time intervals following the educational intervention. Relationships between the types of compliance and sociodemographic characteristics of diabetic patients were performed using the Chi-squared test of associations. The relationship between the types of compliance with educational intervention and glycemic control was explored. The reference range of HbA1c suggested by Chandalia and Krishnaswamy (2002) was used in the study. The HbA1c percentage was classified into three levels: poor, if it was >8%; fair if it fell between 7 and 8%; and good/satisfactory, if it was < 7%. Multinomial logistic regression was used to find out the effect of the independent variables: gender, age groups, educational level, marital status, smoking status, types of compliance with educational intervention (such as having breakfast, lunch, dinner regularly, having small snacks, engaging in exercise, examining the feet daily, and examining the eyes regularly), on the dependent variable: glycemic control HbA1c. Statistical significance was set at P ≤ 0.05.

Results

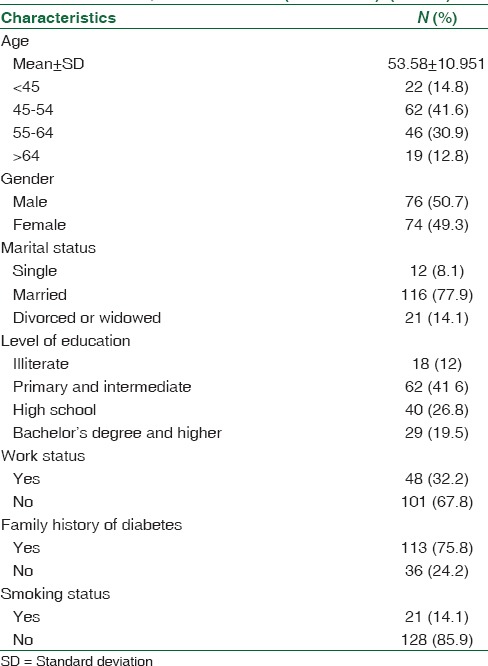

The mean age of the participants, 51% of whom were male was 53.6 ± 10.9 years. The results revealed that most participants (78%) were married; 42% had primary and intermediate school education, 68% did not work, 76% had a family history of diabetes, and 86% were nonsmokers [Table 1].

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of diabetes patients attending the teaching hospital in the Eastern Province, Saudi Arabia (2014-2015) (n=149)

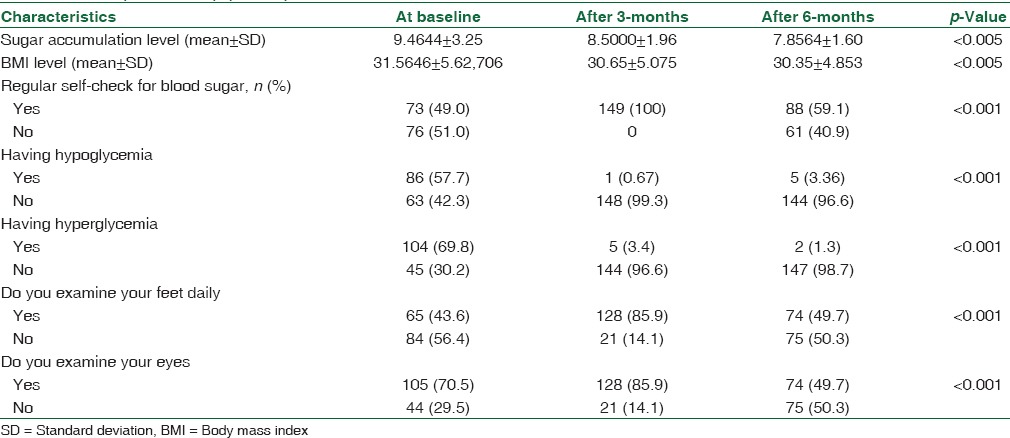

There were significant differences in patients' mean BMI and sugar accumulation level at the three-time intervals (p < 0.005) [Table 2]. The results indicated that there was a reduction in the patients' BMI with a substantial decrease in sugar accumulation level following their participation in the educational program. There was a significant difference among the patients in the three-time periods with respect to their regular health checks for blood sugar (p < 0.05). When compared with the preeducation program stage (49%), there was a considerable increase in the percentage (59%) of patients who began a regular blood sugar check following the training program. A similar trend was noticed in the follow-up measurement of patient compliance with respect to self-check of blood sugar. Of those exposed to the educational program, 100% adopted the practice of checking their blood sugar levels. The table also illustrates that there was a significant difference in the frequency of getting hypoglycemia or hyperglycemia in the 3 time intervals (p < 0.005). The frequency was significantly reduced after the educational intervention. Similarly, there was a significant difference in the frequency of hyperglycemia in the 3 time intervals (p < 0.005). Similarly, it was noticed that patients adopted the habit of examining their feet and eyes daily at 3 months. However, the frequency fell at 6 months.

Table 2.

Clinical characteristics of diabetes patients attending the teaching hospital in the Eastern Province, Saudi Arabia (2014-2015) (n=149)

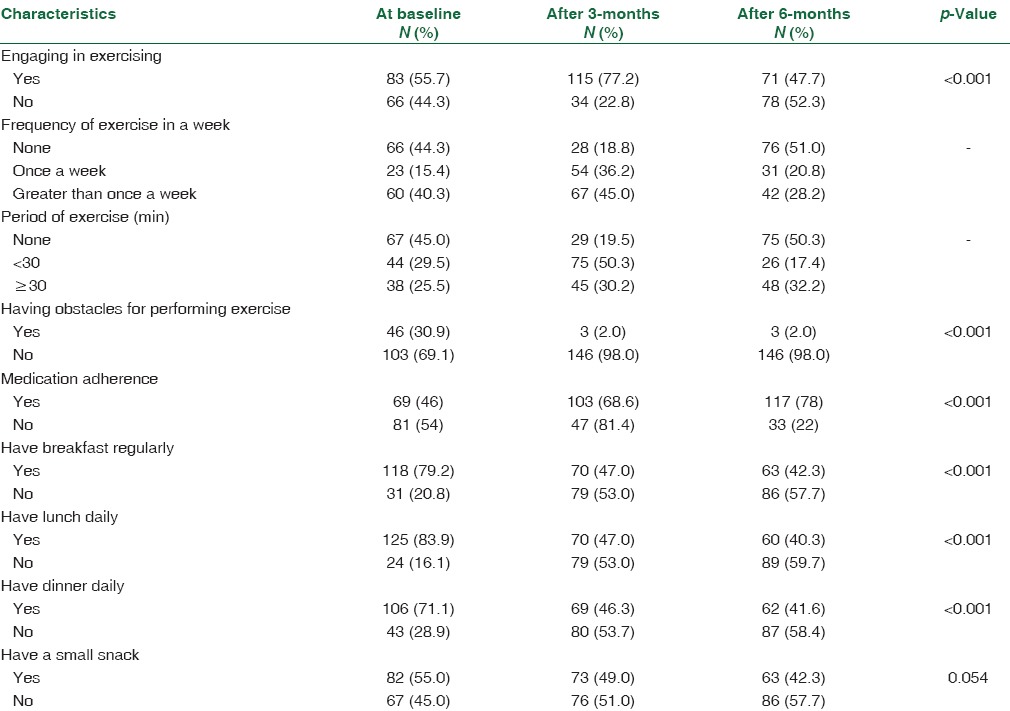

Table 3 shows the lifestyle behavior and patient engagement in exercise as a weekly routine. A significant difference was found with respect to the performance of exercise by the patient in the three-time periods (P < 0.05). There was an increase in the percentage of patients who began to exercise regularly after the educational intervention. However, the percentage dropped at the end of 6-months. The table also shows that the percentage of patients who exercise more than once a week (54%) increased at 3 months but again dropped (28.2%) at 6 months. It is interesting to note that the percentage of patients who did not allocate any time for exercise dropped (19.5%) at 3 months postintervention, but again increased at 6 months postintervention.

Table 3.

Life style behaviors-body mass index level, patients' engagement in performing exercise, medication adherence, and dietary information of diabetes patients at three-time intervals (before the educational program, at end of 3rd month, and at the end of 6th month)

The table also shows patients' compliance to medication adherence measured at three different times. There was a significant difference among the patients in the three-time periods (before the educational intervention, at 3 months later, and at 6 months later (p < 0.005). Overall, improvement in adherence rate of 78% was observed with a decline of nonadherence rate after educational interventions. There were significant differences in the frequency of having breakfast, lunch, and dinner regularly in the three-time intervals (p < 0.005). Post hoc comparisons indicated that there were significant reductions in the frequency of having breakfast, lunch, and dinner following the educational intervention.

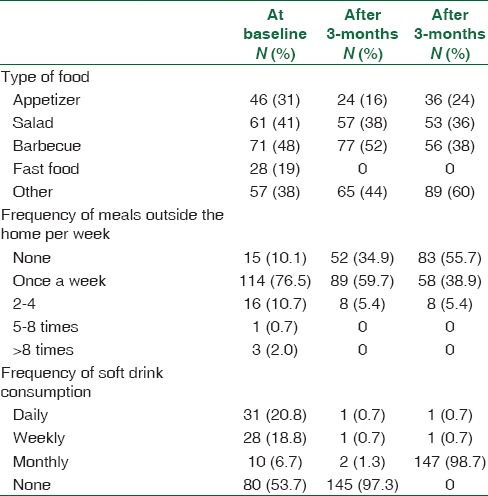

Table 4 shows that the main type of food consumed by patients before the educational intervention was a barbecue (48%) followed by salad (41%). After exposure to the educational intervention at the end of 3rd month, more than half the patients (52%) still had barbecue. However, at the end of 6 months, only 38% and 36% of patients kept having barbecues and salads, respectively. At the end of 6th month and later, around 60% of the patients reported that they ate “other” types of food. It is interesting to note that 3 months after the educational intervention, 16% of the patients reported having reduced their consumption of appetizers, but then this percentage rose to 24% at the end of the 6 months.

Table 4.

Types of food diabetes patients consumed and frequent eating/drinking outside home per week

With regard to the frequency of eating outside (i.e., other than home-cooked food), Table 4 shows that there was a significant reduction in the frequency reported by those who were exposed to the educational intervention. A similar trend was noticed in the frequency of consuming soft drinks. Before exposure to the educational intervention, over 50% of patients reported that they did not have any soft drinks. At the end of the 3rd month following the educational intervention, 97% of the patients reported that they did not consume soft drinks. During the follow-up at the end of the 6th month and later, 98.7% of the patients indicated that they had not had any soft drinks in the past 1 month.

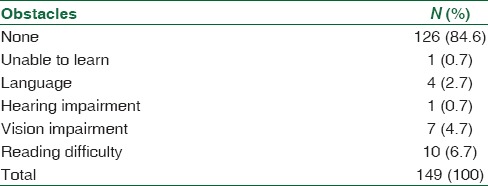

Table 5 shows the main obstacles to patients' health education session. When patients were asked about the main obstacles to their health education session, almost 85% of participants stated there were no obstacles. However, 7% indicated that they had difficulty reading, and 5% had problems with their sight.

Table 5.

The main obstacles to patients' health education session

The results of correlation analysis between types of compliance and the score of HbA1c of the diabetic patients showed that there were statistically significant relationships between control of HbA1c and examination of the feet daily and examining the eyes (p = 0.024; p = 0.024, respectively). The results of the correlation analysis between the types of compliance and diabetic patients' level of education were significant for one type of regimen (i.e., for breakfast dietary regimen) (p = 0.026). No statistically significant differences were noted, giving all items of compliance and genders, age groups, and marital status (p > 0.05).

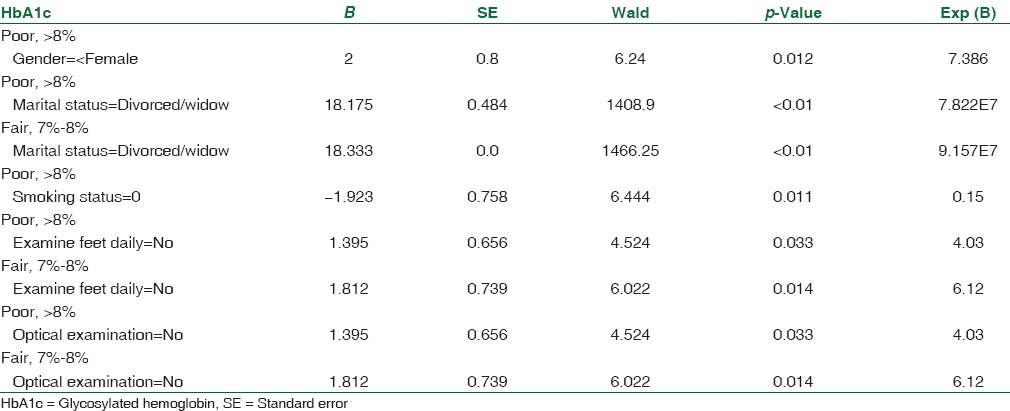

Table 6 shows the results of regression model testing for the effect of independent variables, separately/one at a time, on the score of HbA1c of the diabetic patients. Females were 7.386 times more likely than males to have poor HbA1c compared to HbA1c = good. The females were 1.48 times more likely than males to have a HbA1c = fair compared to HbA1c = good.

Table 6.

Regression model testing for the effect of independent variables, separately, on the score of glycosylated hemoglobin among diabetic patients (results for significant effect only)

Divorced or widowed, smokers, those who did not examine their feet daily, and those who did not examine their eyes regularly, were more likely to have poor HbA1c. The results also show that the individual independent variables, such as age groups, engagement in exercise, having small snacks, having breakfast, lunch, and dinner regularly, had no significant effect on the dependent variable.

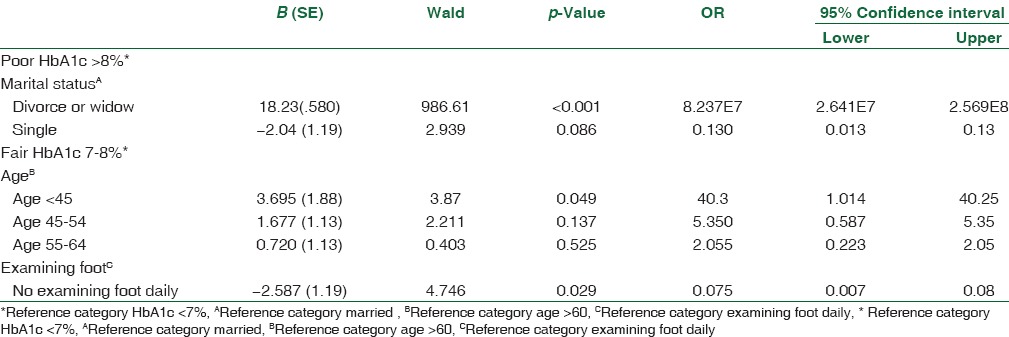

The multinomial regression analysis indicated that marital status, age groups, and daily examination of the feet had a significant effect on the score of HbA1c [Table 7]. A divorced and/or a widowed patient compared to a married patient, patients aged <45 years compared to those more 6 than 60-year-old, and patients who did not examine their feet daily compared to those who did, had poor HbA1c control.

Table 7.

Multinomial logistic regression- factors associated with HbA1c score (results for significant effect only)

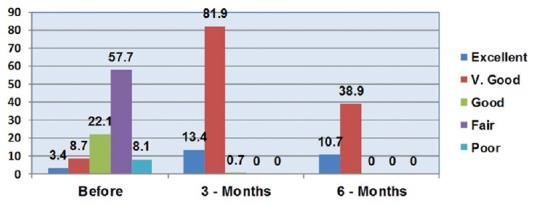

Figure 1 shows that there was an increase in the patient's knowledge of diabetes after regular attendance at the educational program at the three times after educational sessions.

Figure 1.

Patients' knowledge regarding diabetes: Before, 3 months and 6 months of the study

Discussion

Control of diabetes is heavily reliant on the patient's compliance to medical treatment. Although it is difficult to predict the compliance of the patient, its positive effects of self-management training on knowledge, frequency, and accuracy of self-monitoring of blood glucose, self-reported dietary habits, and glycemic control were demonstrated in studies with a short follow-up (6 months).[12,13] In this experimental longitudinal design study, a convenient sample of 150 adult diabetic patients (diagnosed as type-2 diabetes and who had been referred from their endocrinology clinics outside KFHU, to be treated in the outpatients diabetic clinic at KFHU) were recruited. A single baseline measurement was obtained, an intervention administered, and two follow-up measurements were made. The changes in the outcome measurement could, therefore, be associated with the change with the exposure, i.e., intervention.

The present study showed high levels of assimilation of knowledge and skills in the posttest performance. Six months after the application of the educational program, there was a significant reduction in patients' knowledge and performance. This result is similar to Broomfield,[14] who reported that the posttest suggests that participants (students) in his study had a significant capacity of memorization, essential in the retention of knowledge. Nevertheless, in adults, short-term memory is a system in which knowledge is rapidly lost when information is not reinforced, leading to possible forgetting. In his study, assessment after 6 months revealed a significant reduction in the frequency of the number of correct answers of all students (P < 0.001). According to Broomfield, the range of 6 months may have decreased students' performance, interfered in perceptual mechanisms, and levels of attention and thus caused a deficit in knowledge retention that resulted in the loss of information in all courses.

The results of study after the application of the educational program were significant on regular self-checks of blood sugar levels, the frequency of hypoglycemia or hyperglycemia, the frequency of daily examination of the feet and examination of the eyes, and engagement in exercising. There was a positive improvement in such behaviors at 3 months after the educational intervention. However, this improvement lessened at 6 months. In addition, there was a reduction in the frequency of weekly exercise. It is interesting to note that half of the patients at the end of 6 months indicated that they did not allocate any time for exercise. One possible explanation for this might be cultural, in that it discourages people, especially women (half of the patients in this study were women) from frequent exercise. Another reason is the high cost of membership of sports facilities and limited safe public places for exercise.

Moreover, the frequency of patients having breakfast, lunch, and dinner was reduced. One possible explanation for this reduction might be some factors other than the educational intervention per se despite that, almost half (50%) the patients at the end of 6-months of enrollment in the educational program continued to examine their feet and eyes constantly. This result is in line with the results of a study by Cerkoney and Hart,[6] who indicated that a correlation between the consistency levels of diabetics with respect to particular parts of therapeutic regimen (dietary regimen, hypoglycemia management, and foot care). Schwedes et al.[15] reported that self-monitoring was possible for the majority of patients with a good adherence to the monitoring schedule. They found that 87% of the study group continuously observed their blood glucose levels at the end of the follow-up period. Moreover, Wynn Nyunt et al.[16] reported that a significant difference between the two groups was observed in favor of the CM group although both study groups significantly improved A1C. A1C was reduced by 0.60 ± 1.1 U in the intervention group and by 0.50 ± 1.7 U in the control group. It is worth mentioning that the intervention group of their study had lower A1C levels before the intervention. However, they concluded that this observation cannot be attributed to the educational program because of the limited size of the study.

The present study also revealed a significant reduction in the patient's BMI and sugar accumulation level in the three-time periods following exposure to the educational program. This finding is in conformity with the results of the study by Muchmore et al.[7] which demonstrated that body weight was reduced in both intervention groups with no statistically significant contrasts between the groups.

In our study, patients' compliance to medication adherence was measured at three different time intervals. There was a significant difference among the patients in the three-time periods (before the educational intervention, 3 months later, and at 6 months later). Overall improvement in adherence rate of 78% was observed with a decline of the rate of nonadherence after interventions. This result is in accordance with Al-Hayek et al.,[11] who illustrated a relationship between diabetes education and adherence to medication. They found a significant improvement in patients' adherence to medication regimen after the diabetes education session.

Our results revealed that the outcomes of the dietary and exercise adherence demonstrated that patients were more compliant to dietary instructions than to directions on exercise. This result is in line with Ibrahim et al.,[17] who illustrated that the majority of patients complied with the dietary regimen. Our results are also in line with Khattab et al.,[18] who found that there was good compliance to the dietary regimen by 40% of Saudi patients. Other studies have shown that more than one-third and nearly half of the participants did not adhere to diet and exercise recommendations, respectively, but nonadherence to exercise was more common than nonadherence to diet.[19]

Our results found that there were variations and inconsistencies in the frequency of consumption of different types of food over the three-period intervals. This result might be explained, partly, by many factors rather than the educational intervention, such as dietary habit of patients, cultural factors that encourage certain types of food, the extent of self-control to maintain compliance with healthy foods, the readiness of patients to prepare healthy meals for themselves, etc.

Results show that the level of compliance increased with the improvement of the patient's level of knowledge about diabetes. This agrees with the results of Al-Nozha et al.[20] which reported that compliance of diabetic patients with most types of diabetes regimen was low, but a rise in the level of patient's knowledge of diabetes was associated with better compliance. The majority of patients who always took medications as prescribed, and on time and always adhered to a dietary regimen had better glycemic control than others.

The results of the study show that there was no significant relationship between the various aspects of compliance and the sociodemographic characteristics of the patients such as gender, age groups, and marital status. This is comparable to a study of Morisky et al.[21] which indicated that there was no significant relationship between the various aspects of compliance and sociodemographic characteristics of the patients such as marital status.

In this study, the significant relationships found between compliance and both educational level, and the degree of HbA1c control is in conflict with the study by Ibrahim et al.[17] that showed no significant relationships.

Limitation

A major limitation of the study was the absence of a control group, which limits the internal validity of the single hospital. Another was the short follow-up period (6 months)

This study was carried out in one major teaching hospital. Thus, any generalization to cover other hospitals with similar features may be made with caution. Besides, the study was limited to outpatients' clinic

The small sample size was due to the following: first visit to the diabetic outpatient clinic; newly diagnosed T2D; The hours of diabetic outpatient clinic were from 8:00 am to 1:00 pm, 2 days per week only

Further research is needed to address these limitations.

Conclusions

In the current study, patients with T2DM exhibited significant changes in both BMI and sugar accumulation after attending the educational program and showed improved knowledge with regard to regular self-check of blood sugar, dietary regimen, foot care, exercise, and life style behavior. Marital status, age groups, and daily examination of the feet had significant effect on the score of HbA1c. These factors should be considered when planning a health policy to monitor patients with diabetes. We also recommend the conduct of further research on a wider scale using different diabetic centers to get a larger sample with randomized control technique to make the results more general and increase the cogency of the study.

Financial support and sponsorship

The Research was financed by Deanship of Scientific Research at the Imam Abdulrahman Bin Faisal University, Dammam, Saudi Arabia.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgment

We gratefully acknowledge the support of the Deanship of Scientific Research at the Imam Abdulrahman Bin Faisal University for conducting this funded Project. We thank the director of KFHU for assistance in performing these studies. We gratefully acknowledge the support of the entire employees at the diabetic outpatient clinic for their invaluable cooperation and assistance in making this study possible.

References

- 1.Khazrai YM, Defeudis G, Pozzilli P. Effect of diet on type 2 diabetes mellitus: A review. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2014;30(Suppl 1):24–33. doi: 10.1002/dmrr.2515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Elhadd TA, Al-Amoudi AA, Alzahrani AS. Epidemiology, clinical and complications profile of diabetes in Saudi Arabia: A review. Ann Saudi Med. 2007;27:241–50. doi: 10.5144/0256-4947.2007.241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Al-Rubeaan K, Youssef AM, Subhani SN, Ahmad NA, Al-Sharqawi AH, Al-Mutlaq HM, et al. Diabetic nephropathy and its risk factors in a society with a type 2 diabetes epidemic: A Saudi National Diabetes Registry-based study. PLoS One. 2014;9:e88956. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0088956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Improving Type 2 Diabetes Therapy Compliance and Persistence in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabi. IMS Institute. 2016 Jul [Google Scholar]

- 5.World Health Organization. Diabetes. 2013. [Last accessed on 2013 Nov 02]. Available from: http://www.who.int/topics/diabetesmellitus/en/

- 6.Cerkoney KA, Hart LK. The relationship between the health belief model and compliance of persons with diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care. 1980;3:594–8. doi: 10.2337/diacare.3.5.594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Muchmore DB, Springer J, Miller M. Self-monitoring of blood glucose in overweight type 2 diabetic patients. Acta Diabetol. 1994;31:215–9. doi: 10.1007/BF00571954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jin J, Sklar GE, Min Sen Oh V, Chuen Li S. Factors affecting therapeutic compliance: A review from the patient's perspective. Ther Clin Risk Manag. 2008;4:269–86. doi: 10.2147/tcrm.s1458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Balkrishnan R, Rajagopalan R, Camacho FT, Huston SA, Murray FT, Anderson RT. Predictors of medication adherence and associated health care costs in an older population with type 2 diabetes mellitus: A longitudinal cohort study. Clin Ther. 2003;25:2958–71. doi: 10.1016/s0149-2918(03)80347-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Juarez DT, Sentell T, Tokumaru S, Goo R, Davis JW, Mau MM. Factors associated with poor glycemic control or wide glycemic variability among diabetes patients in Hawaii, 2006-2009. Prev Chronic Dis. 2012;9:120065. doi: 10.5888/pcd9.120065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Al-Hayek AA, Robert AA, Al-Dawish MA, Zamzami MM, Sam AE, Alzaid AA. Impact of an education program on patient anxiety, depression, glycemic control, and adherence to self-care and medication in Type 2 diabetes. J Family Community Med. 2013;20:77–82. doi: 10.4103/2230-8229.114766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Federal Bureau of Prisons. Clinical Practice Guidelines Management of diabetes. 2010. [Last accessed on 2011 Aug 01]. Available from: http://www.bop.gov/news/medresources.jsp .

- 13.American Diabetes Association. Checking Your Blood Glucose. [Last accessed on 2011 Aug 03]. Available from: http://www.diabetes.org>LivingWithDiabetes>TreatmentandCare .

- 14.Broomfield R. A quasi-experimental research to investigate the retention of basic cardiopulmonary resuscitation skills and knowledge by qualified nurses following a course in professional development. J Adv Nurs. 1996;23:1016–23. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.1996.tb00084.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schwedes U, Siebolds M, Mertes G. SMBG Study Group. Meal-related structured self-monitoring of blood glucose: Effect on diabetes control in non-insulin-treated type 2 diabetic patients. Diabetes Care. 2002;25:1928–32. doi: 10.2337/diacare.25.11.1928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wynn Nyunt S, Howteerakul N, Suwannapong N, Rajatanun T. Self-efficacy, self-care behaviors and glycemic control among type-2 diabetes patients attending two private clinics in Yangon, Myanmar. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 2010;41:943–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ibrahim NK, Attia SG, Sallam SA, Fetohy EM, El-Sewi F. Physicians' therapeutic practice and compliance of diabetic patients attending rural primary health care units in Alexandria. J Family Community Med. 2010;17:121–8. doi: 10.4103/1319-1683.74325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Khattab MS, Aboifotouh MA, Khan MY, Humaidi MA, al-Kaldi YM. Compliance and control of diabetes in a family practice setting, Saudi Arabia. East Mediterr Health J. 1999;5:755–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kamuhabwa AR, Charles E. Predictors of poor glycemic control in type 2 diabetic patients attending public hospitals in Dar es Salaam. Drug Healthc Patient Saf. 2014;6:155–65. doi: 10.2147/DHPS.S68786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Al-Nozha MM, Al-Maatouq MA, Al-Mazrou YY, Al-Harthi SS, Arafah MR, Khalil MZ, et al. Diabetes mellitus in Saudi Arabia. Saudi Med J. 2004;25:1603–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Morisky DE, Ang A, Krousel-Wood M, Ward HJ. Predictive validity of a medication adherence measure in an outpatient setting. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich) 2008;10:348–54. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-7176.2008.07572.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]