Abstract

BACKGROUND:

Workplace violence against health-care workers is a significant problem worldwide. Nurses are at a higher risk of exposure to violence. Studies available in Saudi Arabia are few.

OBJECTIVES:

The objective of the study was to estimate the prevalence of verbal abuse of nurses at King Fahd Hospital of the University (KFHU) in Khobar, Saudi Arabia, and to identify consequences and the demographic and work-related characteristics associated with it.

MATERIALS AND METHODS:

This cross-sectional study of 391 nurses by total sample was conducted between November and December 2015, using a modified self-administered questionnaire developed by the World Health Organization. Data was entered, and analyzed using SPSS Version 16.0. The descriptive statistics were reported using frequency and percentages for all categorical variables. Chi-squared tests or Fisher's Exact test, as appropriate, were performed to test the associations of verbal abuse with the demographic and work-related characteristics of the participants. Variables with p < 0.05 were considered significant. Logistic regression analysis performed to determine association between verbal abuse and independent variables.

RESULTS:

In a period of 1 year before the study, about three out of ten nurses experienced verbal abuse (30.7%). In the majority of cases, the victims did not report the incidents, mostly because they believed that reporting would yield no positive results. Logistic regression analysis revealed that male nurses, nurses in the emergency department, and nurses who indicated that there were procedures for reporting violence in their workplace were more vulnerable to workplace verbal abuse.

CONCLUSION:

Workplace verbal abuse is a significant challenge in KFHU. For decision makers, it is rather disturbing that a lot of cases go unreported even though procedures for reporting exist. Implementation of an efficient transparent reporting system that provides follow-up investigations is mandatory. In addition, all victims should be helped with counseling and support.

Keywords: Abuse, hospital, nurses, Saudi, verbal, violence, workplace

Introduction

Violence is an increasing problem that threatens the health of the communities worldwide.[1] In the workplace, it is alarming, and health-care providers are especially at a higher risk of violence in the workplace.[2] Almost more than half of health-care workers are exposed to at least one incident of violence within a year.[2] The International Labour Office (ILO), International Council of Nurses (ICN), World Health Organization (WHO), and Public Services International (PSI) established a joint program that defined workplace violence as “Incidents where staff are abused, threatened, or assaulted in circumstances related to their work including commuting to and from work, involving an explicit or implicit challenge to their safety, well-being or health.”[3] Workplace violence can be grouped into physical and psychological.[3] Psychological violence includes verbal abuse, bullying/mobbing, harassment, and threats.[3] Prevalence of workplace violence against health-care workers as reported in studies in the literature varies because of the differences in methodologies, definitions used, and work settings. Some settings have been found to have a high risk for violence either as a result of contact with stressed and aggressive patients such as in emergency departments or with mentally ill patients or patients under the influence of drugs or alcohol as in psychiatry departments.[4,5,6] Zeng et al. conducted a study in two major psychiatric hospitals in China to determine the frequency of violence against psychiatric nurses. They found that the majority of nurses (82.4%) were exposed to at least one type of violent incident during the 6 months preceding the study.[7] The majority of the studies in the literature indicated that psychological violence was the type most experienced, and verbal abuse was the most common form.[2,8] One study conducted in Jordan of emergency nurses showed that verbal abuse occurred five times higher than physical violence.[9] Moreover, nonphysical abuse is a risk factor for physical abuse. Health-care workers who have been exposed to nonphysical violence are seven times at risk to physical violence than those with no history of exposure.[10] A large cross-sectional study carried out on 26,979 nurses in 100 hospitals in Taiwan showed that about 46.3% of nurses were exposed to nonphysical violence in the form of threats, intimidation, verbal violence, or sexual harassment.[11] Associations between violence and demographic and work-related characteristics of victims are conflicting. Many authors agree that young staff,[12] and the less experienced were at a greater risk of violence.[13,14] Both females and males are at risk of violence, but some studies suggest that females are more at risk of psychological violence than males.[2,15] Nurses are on the frontline in the health-care system. They have direct contact with patients and their relatives in the performance of their duties. They are, therefore, less likely to feel safe compared to other health-care workers and more likely to be exposed to violence in their work.[16]

Regarding the perpetrators of workplace violence, many studies have found that patients and/or their relatives are the main culprits.[17,18,19,20] On the other hand, some studies have documented staff members as the main offenders.[2]

It is necessary to report the cases of violence so that a means for prevention could be found,[2] but many studies show that most health-care workers do not report incidents for several reasons: lack of effective policies in the institutions, perception that violence came with the job, absence of physical injury,[6] feelings of being victimized,[21] lack of encouragement to report,[22] and previous dissatisfaction with results.[23]

In recent years, there have been many reports in the mass media of workplace violence against health-care providers in Saudi Arabia, but only a few studies are available. Two studies have been conducted in the primary health-care setting, one in Riyadh city,[24] and the other in Al-Hassa.[25] The authors of the two studies used the same questionnaire. The study in Riyadh showed that 45.6% of 270 primary health-care staff were exposed to violence in period of 1 year, and that verbal attacks accounted for 94.3% of the cases.[24] On the other hand, the study done in Al-Hassa revealed that 28% of 1091 health-care providers were abused, mostly psychologically (89% of cases).[25] Two studies of nurses were conducted in Riyadh city. The first one included 434 nurses in five hospitals.[26] The other involved 370 nurses in the university hospital.[27] Although the intervening period between the two studies is almost 10 years, the results showed that about half of the participating nurses were exposed to workplace violence.[26,27]

This study is expected to provide health-care policy makers with data on the current status of workplace verbal abuse so that rules may be put in place to protect health-care staff in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia from abuse. The aim of the study was to estimate the prevalence of verbal abuse against nurses at King Fahd Hospital of the University (KFHU) in Khobar, Saudi Arabia, and identify consequences and the demographic and work-related characteristics associated with it.

Materials and Methods

This cross-sectional study was conducted at KFHU, Eastern Province, Saudi Arabia, between November and December 2015. KFHU is a referral hospital for the entire eastern province. It provides many services such as inpatient, outpatient, emergency services, operations, and other services. It is a teaching hospital providing training for undergraduate students and postgraduates residents. The study population included all nurses providing direct care to patients. Nurses in the internship program were excluded. Data were collected from all available nurses during the study period. A total of 450 nurses were approached and 391 completed the questionnaire (response rate = 86.9%). The data were collected using a self-administered questionnaire developed by the Joint Programme on Workplace Violence in the Health Sectors of the WHO, the ILO, the ICN, and the PSI.[3] Many authors in the literature from different countries and varying work settings have used this instrument.[28,29,30,31,32,33] The English version of the questionnaire was used since it is the main medium of communication in the hospital. The questionnaire had two main parts. The first part was on demographic and work-related data. The second was on workplace verbal abuse defined as “Promised use of physical or psychological force resulting in fear of harm or other negative consequences to the targeted individuals or groups, including behaviors that humiliate, degrade, or otherwise indicate a lack of respect for the dignity and worth of an individual.” The first question was about whether the respondent had been verbally abused in the workplace in the past 12 months. If yes, how often, followed by questions on the characteristics, how it was dealt with and the consequences of the most recent incident. The researcher omitted some questions in the original questionnaire because they did not conform to the objectives of this study or were not appropriate in the Saudi culture. After these changes were made, two experts in the field revised the questionnaire to enhance the content validity; they agreed to the modifications. The study was approved by the Research Committee of the Family Medicine Joint Residency Program in the Eastern Province of Saudi Arabia, and the University of Dammam Institutional Review Board. All nurses at inpatients units, the emergency department, outpatient clinics, and operating rooms were approached during activity or during break. The investigator explained the aim of the study and the questionnaire to all participants, and verbal consent was taken. Written consent was mentioned in the questionnaire; participation in the study was voluntary. The researcher reassured participants of anonymity of the responses and that there would be no adverse impact on respondents. Information on the questionnaire was to be kept confidential and not used for any purposes other than the research. The collected data were coded, entered, and analyzed using Statistical Package for the Social Sciences Version 16.0 (SPSS Inc. Released 2007. SPSS for Windows, Version16.0. Chicago). The descriptive statistics were reported using frequency and percentages for all categorical variables. Chi-squared tests or Fisher's exact tests were performed to test the associations of verbal abuse with the demographic and work-related characteristics of the participants. Variables with P < 0.05 were considered significant independent variables for the univariate logistic regression analysis. Univariate logistic regression followed by the multivariate logistic regression analysis were done on all significant risk factors and adjusted for the effects of each other to assess the association between the independent variables and exposure to verbal abuse. The Cronbach's alpha reliability coefficient of the questionnaire after the modification was 0.9.

Results

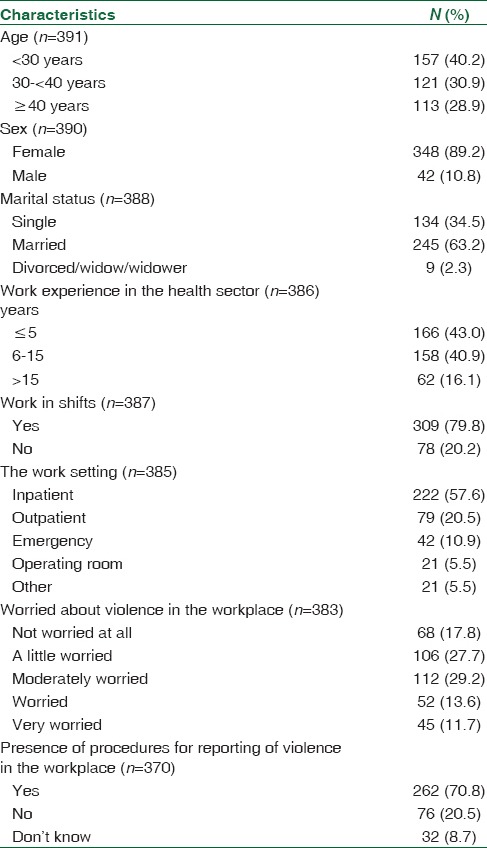

A total of 450 nurses received the questionnaires and 391 of them completed the questionnaires (response rate = 86.9%). Table 1 describes the demographic and work-related characteristics of the participating nurses. A total of 40.2% of the 391 nurses were <30-year-old (n = 157). The majority worked in the inpatient departments (57.6%), followed by 20.5% in the outpatient departments and 10.9% in emergency departments. About one-third of the nurses (29.2%) were moderately worried about workplace violence and 11.7% of them were very worried. Most participants reported that procedures for reporting workplace violence were in place (70.8%).

Table 1.

Demographic and work-related characteristics of nurses in King Fahd Hospital of the University, Khobar (2015), (n=391)

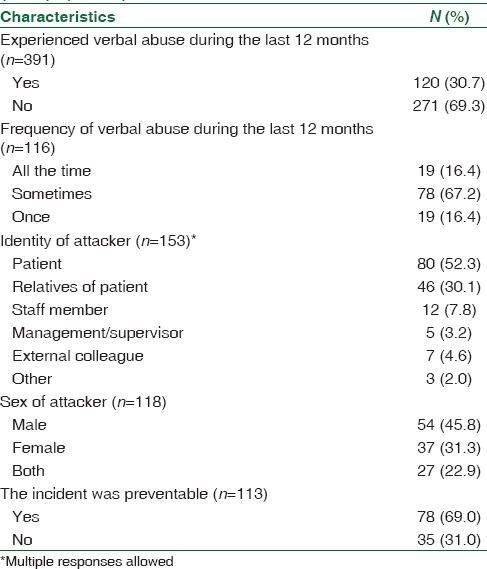

During the year preceding the study, 30.7% of nurses experienced verbal abuse (n = 120). About 67.2% of them said that they were abused sometimes and 16.4% said that they were abused all the time. Patients followed by relatives of patients were the most reported sources of abuse (52.3% and 30.1%, respectively). Staff members were the abusers in 7.8% of cases. Most attackers were males (45.8%) followed by females (31.3%). The majority of abused nurses (69%) believed that the incident was preventable [Table 2].

Table 2.

Prevalence and characteristics of verbal abuse experienced by nurses in King Fahd Hospital of the University during the past 12 months, Khobar (2015), (n=391)

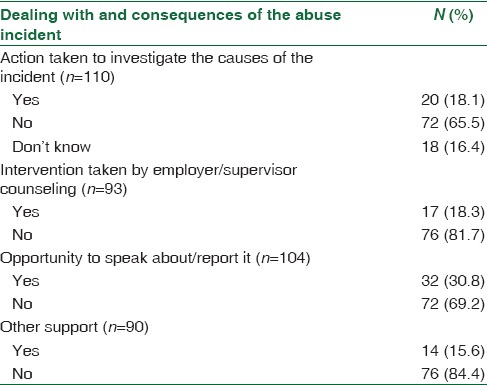

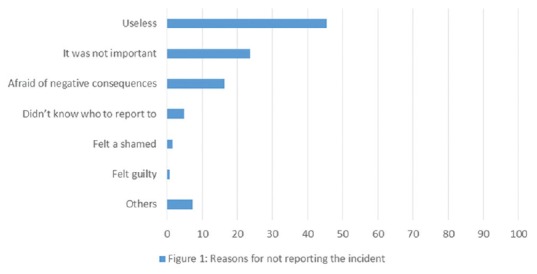

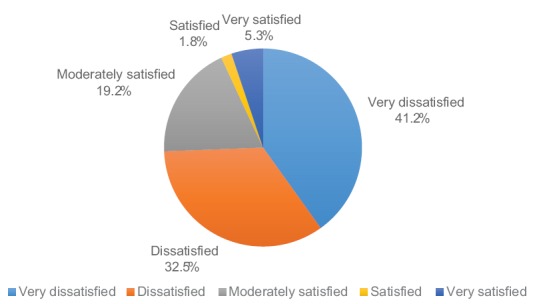

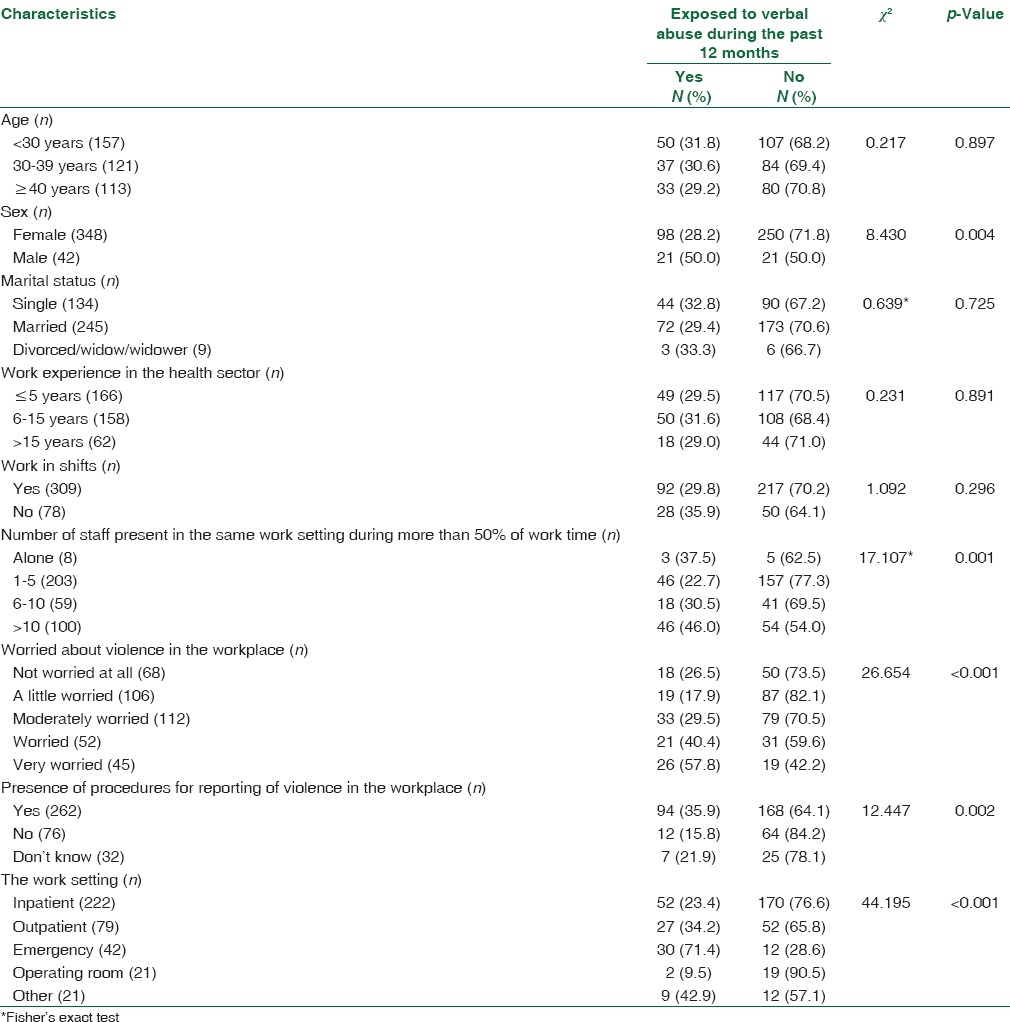

In 65.5% of verbally abused nurses, there had been no investigation into the causes of the abuse. The majority of victims did not receive counseling (81.7%), 69% had no opportunity to speak about the incident or report it, and 84.4% had no support from their supervisors [Table 3]. About 104 (86.7%) of verbally abused nurses did not report the incidents, mostly because they thought the procedure available useless (45.5%), the incident was not important (23.6%), or they were fearful that the consequences of reporting might be adverse (16.3%) [Figure 1]. Most nurses (41.2%) were very dissatisfied and 32.5% were dissatisfied with the manner, in which the incident was handled and only 1.8% of nurses were satisfied [Figure 2].

Table 3.

Dealing with and consequences of verbal abuse experienced by nurses in King Fahd Hospital of the University during the past 12 months, Khobar (2015), (n=120)

Figure 1.

Reasons for not reporting the incident

Figure 2.

Degree of satisfaction of nurses with the manner in which the incident was handled

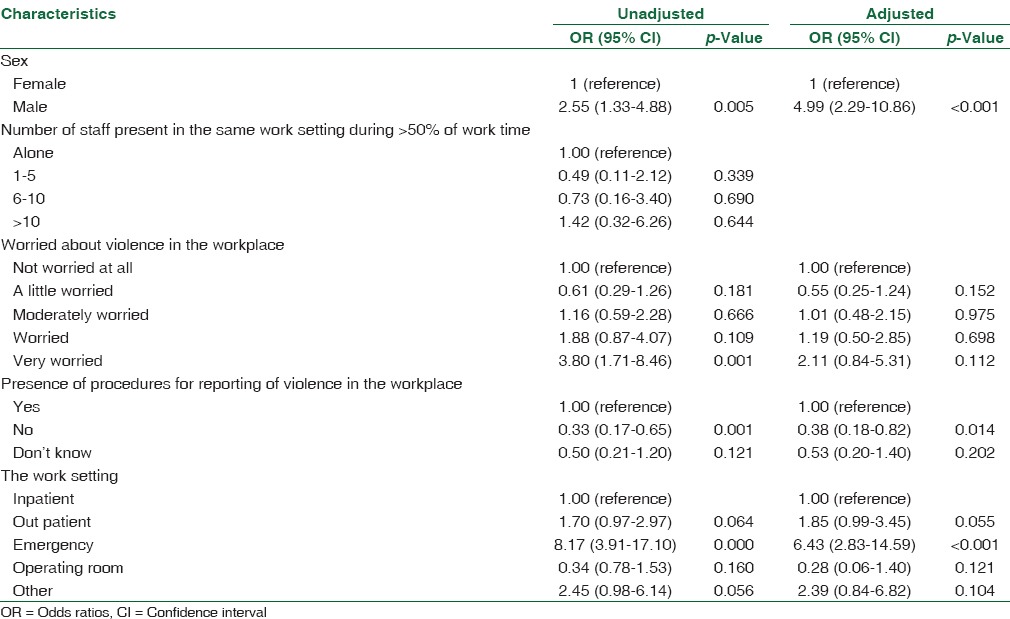

Table 4 describes the association between participants' characteristics and exposure to verbal abuse in the previous 12 months. The results showed that males were abused significantly more than females (p = 0.004). Nurses working with more than ten staff members were exposed to verbal abuse more than those who worked with fewer members of staff (p < 0.001). Incidents of verbal abuse during the last year occurred significantly more among nurses who were more worried about violence in the workplace (p < 0.001). Nurses who knew that there was a procedure for reporting incidents of abuse were exposed to verbal abuse significantly more than those who believed that there was no recourse for redress or had no knowledge of reporting procedure (p = 0.002). Exposure to verbal abuse was significantly more among emergency room nurses (71.4%) than nurses in other departments (p < 0.001). There were no significant associations between exposure to verbal abuse and age, marital status, work experience, and those who worked in shifts.

Table 4.

Exposure to verbal abuse according to demographic and work-related characteristics of the participated nurses, King Fahd Hospital of the University, Khobar (2015), (n=391)

Multivariate logistic regression analysis revealed an increased likelihood of male nurses being verbally abused (odds ratio [OR] = 4.99, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 2.29–10.86) and nurses worked in the emergency department (OR = 6.43, 95% CI: 2.83–14.59). Compared to nurses who reported that there was procedure for reporting workplace violence, nurses who believed that no procedure was available had a reduced risk of verbal abuse (OR = 0.38, 95% CI: 0.18–0.82) [Table 5].

Table 5.

Unadjusted and adjusted association of demographic and work-related characteristics of nurses with exposure to verbal abuse in the past 12 months, King Fahd Hospital of the University, Khobar (2015)

Discussion

The main objective of this study was to estimate the prevalence of workplace verbal abuse of nurses at KFHU in Khobar city in the 12 months preceding the study. A total of 450 nurses received the questionnaires and 391 of them completed questionnaires (response rate = 86.9%). We found that verbal abuse was prevalent with 30.7% of the nurses in the year preceding the study. Owing to the diversity of definitions and methodologies used in the various studies, as well as the different work settings, a comparison of the findings is somewhat difficult. We used a standardized instrument that had been used by many researchers, which made it possible for us to compare our findings with theirs. The prevalence of verbal abuse of health-care workers in Bulgaria is 32.2%, in Brazil (39.5%), in Lebanon (40.9%), in Portugal (27.4%–51%), in Thailand (47.7%), in South Africa (52%–60.1%), and in Australia (67%).[2] There are few studies in Saudi Arabia on workplace violence. Al-Turki et al. reported that 46% of health-care workers in four family and community centers in Riyadh city were exposed to some kind of violence in the period of 12 months before the study.[24] The types of patients, the health-care workers, in Al-Turki et al.'s study dealt with were different from those in our study; their study was conducted at the military medical city where care was provided for soldiers and their families only. The prevalence of violence in our study was lower than that reported by Algwaiz et al. in two public hospitals in Riyadh city, where more than two-thirds of physicians and nurses experienced violence in the year preceding the study.[23] Algwaiz et al. defined violence as “any aggressive behavior against health workers, including physical assaults or verbal aggression.” This definition is wider than what we used in our study. Most perpetrators of verbal abuse in our study were patients and their relatives. This finding agrees with other studies.[9,24,26,34] Staff members were also documented as important sources of verbal abuse. This is an alarming issue; health-care workers should work in a safe and warm environment. Efforts must be made to promote a positive working environment. In line with other studies, we found that most attackers were males.[24,25,26] This could be explained by the fact that Saudi culture is male dominant, and women try to avoid any confrontation or any situation that might put them in a negative light. If there is a problem, the guardian is brought in to resolve the issue. Contrary to many studies, in which most participants indicated that there was no process for reporting violence in their workplace,[18] we found that most nurses believed that these procedures for reporting violence existed (70.8%). However, the majority of nurses did not report the incidents, mostly because they thought of the reporting procedure as “useless.” It seems that most nurses did not trust the reporting system. Moreover, 69% of the nurses who were verbally abused believed that the incidents could have been prevented. This finding is in agreement with other studies, in which most respondents thought the incidents of violence were preventable.[24,35] One wonders about the effectiveness of the reporting procedure if no action is taken to investigate the causes of verbal abuse reported in the current study by 65.5% of the victims. This also can explain why most victims in our study did not report the incidents. In agreement with this explanation, Blando et al. said that lack of action on the report was one of the major barriers to effective implementation of preventive programs on workplace violence.[36] Moreover, the majority of victims in the current study had no support, counseling, or the opportunity to talk about the attack or report it to their supervisors. Consequently, most nurses were very dissatisfied with the manner, in which the incidents of violence were handled. The logistic regression analysis showed that verbal abuse was significantly higher among males, nurses who believed that there was a procedure for reporting in the workplace, and emergency nurses. In agreement with Abbas et al., who found that male nurses experienced violence significantly more than female in primary health-care centers in Egypt,[18] male nurses in the current study were more at risk of verbal abuse than females. In Saudi culture, women are respected, and abuse by men is unacceptable. This finding is contrary to the findings of many authors who reported that verbal abuse was more among females.[15] The current study revealed that participants who believed that there were procedures for reporting incidents of violence were more likely to be verbally abused than those who did not know or who thought that there were no procedures for reporting. Zafar et al. who had similar results suggested that these members of staff were more likely to be called into handle situations where there was aggressive behavior because they were more experienced and aware.[35] This study revealed that emergency nurses were at a greater risk of verbal abuse than nurses in other departments. The results of a study conducted in Egypt comparing the prevalence of workplace violence against nurses in emergency departments and nurses in nonemergency departments demonstrated that verbal abuse was experienced by 60.2% of emergency nurses and by 42.9% of nonemergency nurses.[37]

Conclusion

This study demonstrated that verbal abuse was prevalent among nurses. The following recommendations are suggested: increase the awareness of health-care workers about workplace violence; implement an effective reporting system that demands mandatory follow-up investigations; encourage health-care workers to report incidents with the reassurance that reporting will have no detrimental effect on them; and help all victims with counseling and support. In addition, further research on violence from the attacker's perception is recommended (i.e., circumstances that contribute to the violence).

This study has several limitations. It was a cross-sectional study and can not evaluate temporal and causal relationships of the observed factors. Variations in definitions, methodologies, and work settings of the various studies in the literature made a comparison of the findings difficult. We used a standardized instrument that had been used by many researchers, which allowed us better comparisons with their findings. Nurses were selected from only one hospital in the Eastern Province of Saudi Arabia, so we cannot generalize the results of this study to cover all health-care workers in the kingdom. The primary objective was to assess the exposure of violence during the previous year; this may have potentiated the risk of recall bias. We tried to limit the recall bias by limiting the questions to the previous year and the last experienced incident. On the other hand, a prospective study of the incidence will be expensive and difficult to apply. Moreover, depending on officially reported cases to estimate the prevalence of violence will result in an underestimation of the problem, for as shown in the current study, the majority of cases of violence have gone unreported.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgment

The researchers acknowledges the help of Miss. Shrooq AlGhamdi in the creation of the database and the help of Dr. Danah AlShamlan, Dr. Fatima Fakhroo, Dr. Iba AlFawaz, Dr. Reema AlOtaibi, and Dr. Sarah AlArifi in the data collection process. We also thank Dr. Reem AlShamlan and Dr. Abeer AlShamlan, for their help in the editing process. The cooperation from nurses who participated in this study is highly appreciated. The content is under the responsibility of the researchers and does not represent the views of KFHU or Imam Abdulrahman Bin Faisal University.

References

- 1.Krug EG, Dahlberg LL, Mercy JA, Zwi AB, Lozano R, editors. World Report on Violence and Health. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2002. [Last accessed on 2015 Oct 15]. Available from: http://www.whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2002/9241545615_eng.pdf?ua=1 . [Google Scholar]

- 2.Martino V. Workplace Violence in the Health Sector: Country Case Studies. Brazil, Bulgaria, Lebanon, Portugal, South Africa, Thailand and an Additional Australian Study. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Joint Programme on Workplace Violence in the Health Sector of the International Labor Office. The International Council of Nurses, The World Health Organization, and the Public Services International. [Last accessed on 2015 Oct 15]. Available from: http://www.who.int/violence_injury_prevention/violence/interpersonal/en/WVquestionnaire.pdf .

- 4.Magnavita N, Heponiemi T. Violence towards health care workers in a Public Health Care Facility in Italy: A repeated cross-sectional study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2012;12:108. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-12-108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fujita S, Ito S, Seto K, Kitazawa T, Matsumoto K, Hasegawa T, et al. Risk factors of workplace violence at hospitals in Japan. J Hosp Med. 2012;7:79–84. doi: 10.1002/jhm.976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Speroni KG, Fitch T, Dawson E, Dugan L, Atherton M. Incidence and cost of nurse workplace violence perpetrated by hospital patients or patient visitors. J Emerg Nurs. 2014;40:218–28. doi: 10.1016/j.jen.2013.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zeng JY, An FR, Xiang YT, Qi YK, Ungvari GS, Newhouse R, et al. Frequency and risk factors of workplace violence on psychiatric nurses and its impact on their quality of life in China. Psychiatry Res. 2013;210:510–4. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2013.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Samir N, Mohamed R, Moustafa E, Abou Saif H. Nurses' attitudes and reactions to workplace violence in obstetrics and gynaecology departments in Cairo hospitals. East Mediterr Health J. 2012;18:198–204. doi: 10.26719/2012.18.3.198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.ALBashtawy M. Workplace violence against nurses in emergency departments in Jordan. Int Nurs Rev. 2013;60:550–5. doi: 10.1111/inr.12059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lanza ML, Zeiss RA, Rierdan J. Non-physical violence: A risk factor for physical violence in health care settings. AAOHN J. 2006;54:397–402. doi: 10.1177/216507990605400903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wei CY, Chiou ST, Chien LY, Huang N. Workplace violence against nurses – Prevalence and association with hospital organizational characteristics and health-promotion efforts: Cross-sectional study. Int J Nurs Stud. 2016;56:63–70. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2015.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schablon A, Zeh A, Wendeler D, Peters C, Wohlert C, Harling M, et al. Frequency and consequences of violence and aggression towards employees in the German healthcare and welfare system: A cross-sectional study. BMJ Open. 2012;2:e001420. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2012-001420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liu H, Zhao S, Jiao M, Wang J, Peters DH, Qiao H, et al. Extent, nature, and risk factors of workplace violence in public tertiary hospitals in China: A cross-sectional survey. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2015;12:6801–17. doi: 10.3390/ijerph120606801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kitaneh M, Hamdan M. Workplace violence against physicians and nurses in Palestinian public hospitals: A cross-sectional study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2012;12:469. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-12-469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Al-Omari H. Physical and verbal workplace violence against nurses in Jordan. Int Nurs Rev. 2015;62:111–8. doi: 10.1111/inr.12170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kansagra SM, Rao SR, Sullivan AF, Gordon JA, Magid DJ, Kaushal R, et al. A survey of workplace violence across 65 U.S. emergency departments. Acad Emerg Med. 2008;15:1268–74. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2008.00282.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Talas MS, Kocaöz S, Akgüç S. A survey of violence against staff working in the emergency department in Ankara, Turkey. Asian Nurs Res (Korean Soc Nurs Sci) 2011;5:197–203. doi: 10.1016/j.anr.2011.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Abbas MA, Fiala LA, Abdel Rahman AG, Fahim AE. Epidemiology of workplace violence against nursing staff in Ismailia governorate, Egypt. J Egypt Public Health Assoc. 2010;85:29–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Khademloo M, Moonesi FS, Gholizade H. Health care violence and abuse towards nurses in hospitals in North of Iran. Glob J Health Sci. 2013;5:211–6. doi: 10.5539/gjhs.v5n4p211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Teymourzadeh E, Rashidian A, Arab M, Akbari-Sari A, Hakimzadeh SM. Nurses exposure to workplace violence in a large teaching hospital in Iran. Int J Health Policy Manag. 2014;3:301–5. doi: 10.15171/ijhpm.2014.98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.AbuAlRub RF, Al-Asmar AH. Psychological violence in the workplace among Jordanian hospital nurses. J Transcult Nurs. 2014;25:6–14. doi: 10.1177/1043659613493330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hogarth KM, Beattie J, Morphet J. Nurses' attitudes towards the reporting of violence in the emergency department. Australas Emerg Nurs J. 2016;19:75–81. doi: 10.1016/j.aenj.2015.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Algwaiz WM, Alghanim SA. Violence exposure among health care professionals in Saudi public hospitals. A preliminary investigation. Saudi Med J. 2012;33:76–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Al-Turki N, Afify AA, AlAteeq M. Violence against health workers in family medicine centers. J Multidiscip Healthc. 2016;9:257–66. doi: 10.2147/JMDH.S105407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.El-Gilany AH, El-Wehady A, Amr M. Violence against primary health care workers in Al-Hassa, Saudi Arabia. J Interpers Violence. 2010;25:716–34. doi: 10.1177/0886260509334395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mohamed AG. Work-related assaults on nursing staff in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. J Family Community Med. 2002;9:51–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Alkorashy HA, Al Moalad FB. Workplace violence against nursing staff in a Saudi university hospital. Int Nurs Rev. 2016;63:226–32. doi: 10.1111/inr.12242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Steinman S. Workplace Violence in the Health Sector – Country Case Study. Working paper. South Africa, Geneva: ILO/ICN/WHO/PSI Joint Programme on Workplace Violence in the Health Sector; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Deeb M. Workplace Violence in the Health Sector – Country Case Study. Working paper. Lebanon, Geneva: ILO/ICN/WHO/PSI Joint Programme on Workplace Violence in the Health Sector; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ferrinho P, Antunes A, Biscaia A, ConceiÁo C, Fronteira I, Craveiro I, et al. Workplace Violence in the Health Sector – Portuguese Case Studies. Working Paper. Geneva: ILO/ICN/WHO/PSI Joint Programme on Workplace Violence in the Health Sector; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Palácios M, Loureiro dos Santos M, Barros do Val M, Medina M, de Abreu, M, Soares Cardoso L, et al. Workplace Violence in the Health Sector – Country Case Study. Working Paper. Brazil, Geneva: ILO/ICN/WHO/PSI Joint Programme on Workplace Violence in the Health Sector; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sripichyakan K, Thungpunkum P, Supavititpatana B. Workplace Violence in the Health Sector – A Case Study. Working Paper. Thailand, Geneva: ILO/ICN/WHO/PSI Joint Programme on Workplace Violence in the Health Sector; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tomev L, Daskalova N, Ivanova V. Workplace Violence in the Health Sector – Country Case Study. Working Paper. Bulgaria, Geneva: ILO/ICN/WHO/PSI Joint Programme on Workplace Violence in the Health Sector; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jiao M, Ning N, Li Y, Gao L, Cui Y, Sun H, et al. Workplace violence against nurses in Chinese hospitals: A cross-sectional survey. BMJ Open. 2015;5:e006719. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2014-006719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zafar W, Siddiqui E, Ejaz K, Shehzad MU, Khan UR, Jamali S, et al. Health care personnel and workplace violence in the emergency departments of a volatile metropolis: Results from Karachi, Pakistan. J Emerg Med. 2013;45:761–72. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2013.04.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Blando J, Ridenour M, Hartley D, Casteel C. Barriers to effective implementation of programs for the prevention of workplace violence in hospitals. Online J Issues Nurs. 2015;20:pii: 5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Abou-ElWafa HS, El-Gilany AH, Abd-El-Raouf SE, Abd-Elmouty SM, El-Sayed Rel-S. Workplace violence against emergency versus non-emergency nurses in Mansoura University Hospitals, Egypt. J Interpers Violence. 2015;30:857–72. doi: 10.1177/0886260514536278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]