Abstract

Background:

Nutritional deficiencies are known to be associated with hair loss; however, the exact prevalence is not known.

Aims:

The aim of this study is to evaluate the prevalence of nutritional deficiencies in participants with hair loss.

Materials and Methods:

In this cross-sectional study, 100 enrolled participants were divided into telogen effluvium (TE), male-pattern hair loss (MPHL), and female-pattern hair loss (FPHL) based on the type of hair loss. All participants underwent laboratory estimation for micronutrients and amino acid levels.

Results:

Participants with hair loss showed varied amino acid and micronutrient deficiencies across all types of hair loss. Nutritional status did not vary much between the types of hair loss. Among the essential amino acids, histidine deficiency was seen in >90% of participants with androgenic alopecia and 77.78% of participants with TE while leucine deficiency was seen 98.15% of participants with TE and 100% with FPHL. Valine deficiency was also very common across alopecia subtypes. Among the nonessential amino acids, alanine deficiency was observed in 91.67% FPHL, 91.18% MPHL, and 90.74% TE. Cysteine deficiency was present in 55.58% and 50% of participants with MPHL and TE, respectively. A relatively higher proportion of participants with TE had iron deficiency compared to androgenic alopecia (P = 0.069). Zinc deficiency was seen in 11.76% of participants with MPHL while copper deficiency was seen in 29.41% and 31.48% of participants with MPHL and TE, respectively.

Conclusion:

Nutritional deficiency is a common problem in participants with hair loss irrespective of the type of alopecia. The findings of our study suggest need for identification and correction of nutritional deficiencies in patients with hair loss.

Keywords: Amino acid deficiency, androgenetic alopecia, micronutrient deficiency, nutritional deficiency, telogen effluvium

INTRODUCTION

The etiology of hair loss is multifactorial with contributions from genetic predisposition, pathological states, pharmacotherapy, and nutritional inadequacies.[1,2,3,4] While nutritional deficiencies can lead to hair loss, exact data are often lacking. Furthermore, evidence base to support routine screening of nutritional deficiencies and the efficacy of nutritional supplementation in reversing hair loss is still in accrual and is currently inconclusive. Nutritional inadequacies are a wide-spread population problem in India.[5,6] A relative paucity of data on the specificity of a causal association between hair loss and nutrition in Indian trichology merits investigation.

Objective

The objective of this study was to find the prevalence of nutritional deficiencies in Indian participants with hair loss.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

In this cross-sectional study, a total of 100 adult participants between 18 and 40 years of age with diffuse hair loss, i.e., generalized nonscarring loss of scalp hair with >100 strands lost/day continuously irrespective of duration were enrolled in the study. Patients with alopecia areata or cicatricial hair loss and those reporting usage of nutritional supplements in the past 6 weeks were not included in this study. Similarly, pregnant women, postmenopausal women, and patients with recent history of immunosuppressant therapies or chemotherapy were also not enrolled in the study.

All enrolled study participants underwent scalp examination with a hair pull test and trichoscopy after the detail medical history. Hair pull test was performed by pulling 20–60 hairs between thumb, index, and middle finger. Tests were considered positive if >10% of the hairs got pulled away from scalp. Based on the clinical examination, diagnosis of telogen effluvium (TE), male-pattern alopecia (MPHL), and female-pattern alopecia (FPHL) was made. All participants underwent laboratory investigations which included iron profile, serum vitamin B12 level, amino acid levels, folate, serum zinc, serum copper, and biotinidase level. Vitamin B12 and serum folate were analyzed by chemiluminescence immunoassays. Spectrophotometric tests were used to estimate biotinidase levels and iron profiles. Levels of serum copper and serum zinc were assessed using inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry while amino acids levels were assessed using liquid chromatography–MS.

The study was conducted between October 2015 and December 2015. The study was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee. A signed informed consent was obtained from all the participants in the study.

Statistical analysis

The data were analyzed using GNU PSPP (GNU Project, Boston, MA, USA). Continuous variables are summarized using number (frequency), mean, and standard deviation while categorical variables are summarized using frequency and percentage. Means were compared across groups using t-test, and proportions were compared with Karl Pearson's Chi-square test. Level of significance (α) was set at 0.05.

RESULTS

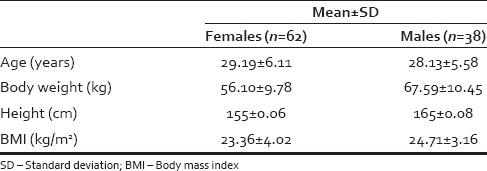

The study included 62 females and 38 males. The demographic characteristics of study participants are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics

Analysis of comorbid medical illness showed the presence of hypertension in five participants and obesity in six participants. Four females (6.45%) had hypertension and obesity each while 2.63% and 5.26% of males had hypertension and obesity, respectively. Out of 100, MPHL was seen in 34 cases, FPHL in 12 cases, and TE in 54 cases.

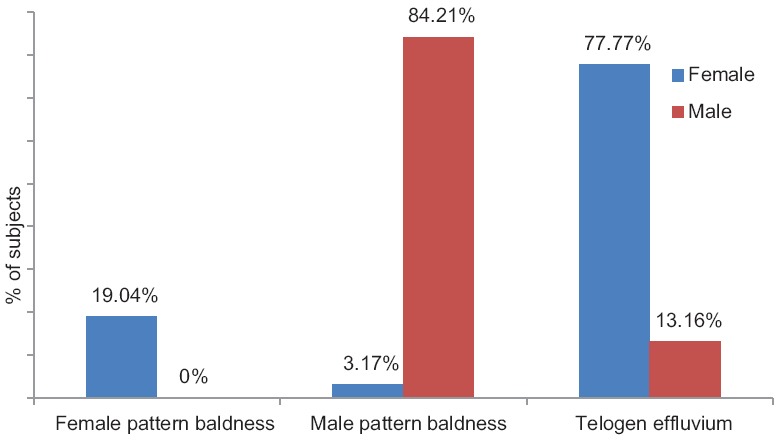

MPHL was present in 84.21% of males. TE and FPHL were present in 77.77% and 19.04% of females, respectively [Figure 1].

Figure 1.

Types of hair loss in study participants

History of smoking and alcoholism was present in 31.58% and 34.21% of males while the corresponding percentages of females were 1.61% and 1.61%, respectively. The difference between males and females in smoking and alcoholism was statistically significant (P < 0.001).

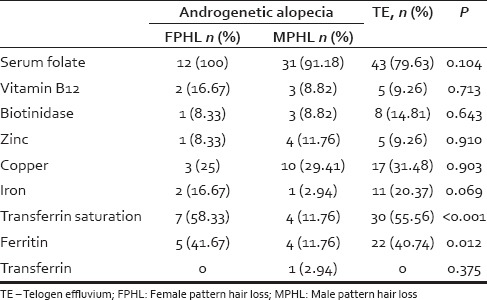

Table 2 presents the proportions of patients with micronutrient deficiencies categorized according to the type of hair loss

Table 2.

Proportion of patients with micronutrient deficiencies and hair loss

A relatively higher proportion of participants with TE had iron deficiency [P = 0.069; Table 2]. Transferrin saturation and ferritin levels were low in patients with FPHL and TE as compared to patients with MPHL [Table 2]. No significant difference in other micronutrients was observed between TE and androgenetic alopecia.

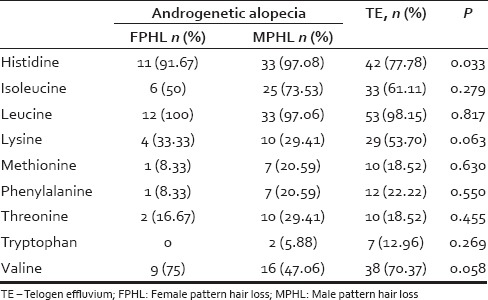

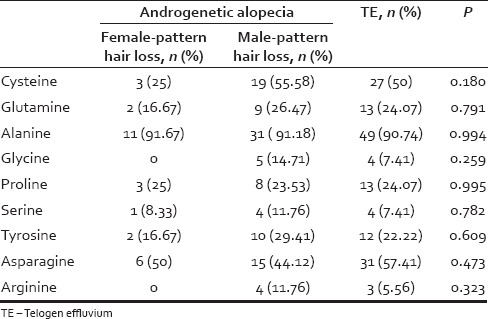

Deficiencies of essential amino acids [Table 3] and nonessential [Table 4] were noted in participants with hair loss, but these deficiencies were not specific to the type of hair loss as indicated by the “p” values comparing androgenetic alopecia versus TE [Tables 3 and 4] except histidine. Histidine deficiency was seen in 77.78% of participants with TE compared to 91.67% and 97.08% of those with FPHL and MPHL, respectively [Table 3].

Table 3.

Deficiencies of essential amino acids in patients with androgenetic alopecia and telogen effluvium

Table 4.

Deficiencies of nonessential amino acids in patients with androgenetic alopecia and telogen effluvium

Leucine deficiency was observed in all participants with FPHL and 97.06% with MPHL. A total of 98.15% of participants with TE were deficient in leucine. Valine deficiency was observed in 75%, 47.06%, and 70.37% of participants with FPHL, MPHL, and TE, respectively. Isoleucine deficiency was observed in 73.53% of participants with MPHL while 61.11% of participants with TE were deficient in it. Fifty percent participants with FPHL were deficient in isoleucine while 53.70% of TE participants had deficiency of lysine [Table 3].

Alanine deficiency was present in 91.67%, 91.18%, and 90.74% of participants with FPHL, MPHL, and TE, respectively. Fifty percent and 55.58% of participants with TE and MPHL were deficient in cysteine, respectively. Asparagine deficiency was seen in 57.41% of participants with TE and 50% with FPHL.

DISCUSSION

Hair loss is a common problem in the community which causes an adverse impact on the psychological aspects of a person. Although nutritional deficiencies are implicated in the pathogenesis of hair loss, there is paucity of the comprehensive laboratory analysis of nutritional status in participants with hair loss. This study was conducted to evaluate the prevalence of various micronutrients such as essential and nonessential amino acids, vitamins, and minerals in participants with hair loss. The results of the current study indicate that patients with hair loss have a noticeable deficiency of some but not all micronutrients and amino acids.

A study conducted by Durusoy et al. demonstrated that trichodynia in diffuse hair loss is not associated with serum levels of zinc, folate, or Vitamin B12.[7] Other studies have also reported no association between Vitamin B12 and folate levels in patients with alopecia areata.[8,9] However, in the current study, we observed a very high prevalence of folate deficiency in patients with androgenetic alopecia and TE. Folate deficiency may perhaps be a population problem in India, and specific association to hair loss may need further evaluation. In a recent study, lower levels of zinc but not copper were found to be significantly associated with hair loss in Korean patients.[10] Another study by Mussalo-Rauhamaa et al. showed lower serum copper concentration in alopecia universalis patient group.[11] Thus, a consensus regarding the association of zinc and copper levels with hair loss is elusive at the moment. In the current study, copper and zinc deficiency was observed in about 30% and 10% of participants, respectively.

Iron deficiency is common in women with hair loss.[4] This observation is supported by the results of our study. A relatively higher proportion of participants with TE had iron deficiency. However, close to 78% of patients with TE were females. Furthermore, deficient transferrin saturation and ferritin levels are more in patients with TE and FPHL. Thus, iron deficiencies noted here may actually be related to gender rather than the type of hair loss.

Suboptimal intake of the essential amino acid (l-lysine) may be associated with increased and persistent hair shedding and reduced hair volume.[4] Indians obtain a major part of proteins and amino acids from cereals and legumes. Deficiency of lysine in many Indian diets may be explained by some observations. Cereals are comparatively deficient in lysine, and maillard-type reactions during food preparation have potential to aggravate lysine deficiency in cereals.[12] Results of the current study indicate that along with lysine, Indian participants with hair loss may have a high prevalence of histidine, isoleucine, and leucine deficiency. Alanine deficiency was also highly prevalent in these study participants. More than 90% of participants of subtypes of hair loss had alanine deficiency. Moreover, 50% or more participants with TE and MPHL also had cysteine deficiency. Asparagine deficiency was common in participants with TE and FPHL.

In the study, we observed nutritional deficiencies, especially of amino acids such as histidine, leucine, valine, alanine, and cysteine in participants with hair loss. The deficiencies were not particular to the type of hair loss. These observations underline the importance of nutritional status in participants with hair loss irrespective of the type of baldness. Nutritional deficiencies could be a population problem, and the specific association of these deficiencies to hair loss may need further evaluation.

Further studies assessing the impact of nutritional supplement on laboratory values and hair growth in participants with hair loss would provide more insights into the causal relationship between the deficiency and hair loss.

CONCLUSION

The results of our study demonstrate noticeable prevalence of amino acid and micronutrient deficiencies in otherwise healthy participants with hair loss irrespective of the type of alopecia. From the observations of the study, it appears that the nutritional status plays an important role in all types of hair loss. In people with nutritional deficiencies, supplementation might be useful in preventing hair loss.

Financial support and sponsorship

The authors would like to thank Abbott Healthcare Pvt. Ltd. for funding the study through a research grant.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Yazdan P. Update on the genetics of androgenetic alopecia, female pattern hair loss, and alopecia areata: Implications for molecular diagnostic testing. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2012;31:258–66. doi: 10.1016/j.sder.2012.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Woods EA, Foisy MM. Antiretroviral-related alopecia in HIV-infected patients. Ann Pharmacother. 2014;48:1187–93. doi: 10.1177/1060028014540451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shin H, Jo SJ, Kim DH, Kwon O, Myung SK. Efficacy of interventions for prevention of chemotherapy-induced alopecia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Cancer. 2015;136:E442–54. doi: 10.1002/ijc.29115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rushton DH. Nutritional factors and hair loss. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2002;27:396–404. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2230.2002.01076.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vijayaraghavan K. Control of micronutrient deficiencies in India: Obstacles and strategies. Nutr Rev. 2002;60(5 Pt 2):S73–6. doi: 10.1301/00296640260130786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kotecha PV. Micronutrient malnutrition in India: Let us say “no” to it now. Indian J Community Med. 2008;33:9–10. doi: 10.4103/0970-0218.39235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Durusoy C, Ozenli Y, Adiguzel A, Budakoglu IY, Tugal O, Arikan S, et al. The role of psychological factors and serum zinc, folate and Vitamin B12 levels in the aetiology of trichodynia: A case-control study. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2009;34:789–92. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2230.2008.03165.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gonul M, Cakmak SK, Soylu S, Kilic A, Gul U. Serum Vitamin B12, folate, ferritin, and iron levels in Turkish patients with alopecia areata. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2009;75:552. doi: 10.4103/0378-6323.55430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ertugrul DT, Karadag AS, Takci Z, Bilgili SG, Ozkol HU, Tutal E, et al. Serum holotranscobalamine, Vitamin B12, folic acid and homocysteine levels in alopecia areata patients. Cutan Ocul Toxicol. 2013;32:1–3. doi: 10.3109/15569527.2012.683499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kil MS, Kim CW, Kim SS. Analysis of serum zinc and copper concentrations in hair loss. Ann Dermatol. 2013;25:405–9. doi: 10.5021/ad.2013.25.4.405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mussalo-Rauhamaa H, Lakomaa EL, Kianto U, Lehto J. Element concentrations in serum, erythrocytes, hair and urine of alopecia patients. Acta Derm Venereol. 1986;66:103–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rutherfurd SM, Bains K, Moughan PJ. Available lysine and digestible amino acid contents of proteinaceous foods of India. Br J Nutr. 2012;108 Suppl 2:S59–68. doi: 10.1017/S0007114512002280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]