Abstract

Purpose of review

Recent literature on racial or ethnic discrimination and mental health was reviewed to assess the current science and identify key areas of emphasis for social epidemiology. Objectives of this review were to: 1) Determine whether there have been advancements in the measurement and analysis of perceived discrimination; 2) Identify the use of theories and/or frameworks in perceived discrimination and mental health research; and 3) Assess the extent to which stress buffers are being considered and evaluated in the existing literature.

Recent findings

Metrics and analytic approaches used to assess discrimination remain largely unchanged. Theory and/or frameworks such as the stress and coping framework continue to be underused in majority of the studies. Adolescents and young adults experiencing racial/ethnic discrimination were at greater risk of adverse mental health outcomes, and the accumulation of stressors over the life course may have an aggregate impact on mental health. Some growth seems evident in studies examining the mediation and moderation of stress buffers and other key factors with the findings suggesting a reduction in the effects of discrimination on mental health.

Summary

Discrimination scales should consider the multiple social identities of a person, the context where the exposure occurs, how the stressor manifests specifically in adolescents, the historical traumas, and cumulative exposure. Life course theory and intersectionality may help guide future work. Despite existing research, gaps remain in in elucidating the effects of racial and ethnic discrimination on mental health, signaling an opportunity and a call to social epidemiologists to engage in interdisciplinary research to speed research progress.

Keywords: racial/ethnic, discrimination, mental health, coping, social epidemiology, stress, psychological distress

Introduction

Over two decades of research have shown that subjective or perceived exposure to racial or ethnic discrimination has deleterious effects on both physical and mental health for African Americans, and recent studies report similar findings for Asian Americans, Latinos, and other ethnic groups [1]. Whether racial discrimination, racism, ethnic discrimination, or cultural racism, often used interchangeably, the shared meaning of these terms is the unfair treatment that members of marginalized racial and ethnic groups experience because of their phenotypical or linguistic characteristics and cultural practices. Perceived exposure to discrimination (broadly stated here to imply unfair treatment due to one’s race or ethnicity) has been conceptualized as a unique chronic stressor [1–3]. Consistent with other stressors, perceived discrimination can elicit variable emotional and behavioral responses that have been hypothesized to adversely affect mental health [3].

Several reviews have been published characterizing the state of the science on discrimination and mental health with a preponderance of the evidence showing that discrimination has a negative impact on mental health status and as a result contributes to declines in physical health [1,3–5]. Pascoe and Smart-Richman conducted a meta-analysis that included 107 papers on discrimination and mental health examining a total of 500 statistical associations, with 69% (345 of the 500 studies) showing a statistically significant association between high perceived discrimination and poor mental health [6]. Of 26 articles included in a 2009 review of discrimination and mental health among children, a positive association between discrimination and poor mental health was found in most studies [7]. The socio-environment and developmental stage of adolescents may greatly influence how they perceive the discriminatory encounter(s) [2,5]. In addition, children may experience discrimination vicariously through their parents, and the parents’ response to stressors may influence their children [2,5].

The current paper uses a conceptual stress and coping framework that depicts the chronic stress nature of perceived discrimination to provide an update of the United States (U.S.) literature within areas of relevance to social epidemiology. We frame this review to achieve the following objectives: 1) Determine whether there have been advancements in the measurement and analysis of perceived discrimination; 2) Identify the theories and/or frameworks used to guide research on perceived discrimination and mental health; and 3) Assess the extent to which stress buffers are being considered and evaluated in the existing literature.

Methods

We identified peer-reviewed U.S.-based journal articles published on perceived race or ethnicity discrimination and mental health within the past five years, 2011–2016. Electronic databases used for the search included PubMed, PsycInfo, CINAHL, and Scopus. The literature search strategy consisted of the following key words: (“unfair treatment” or “discrimination” or “racism” or “prejudice”) and (“race” or “ethnicity” or “African American” or “African American” or “Latino” or “Latina” or “Asian American” or “Muslim” or “Islamic” or “Native American” or “Hispanic” or “Puerto Rican” or (“Cuban and “American”) or (“Mexican and “American”) or (“Dominican” and “American”) or “culture”) and (“mental health” or “depression” or “anxiety” or “post-traumatic stress disorder” or “PTSD”) or (“race-based traumatic stress injury” or “historical trauma” or “historical trauma response” or “emotional distress” or “intrusion” or “vigilance” or “anger” or “avoidance”) and (“psychology*” or “stress” or “stressor”). There were 712 articles identified upon removing duplicates.

To identify articles that measured discrimination as a primary variable in relation to mental health, the authors reviewed the titles and abstracts of each study using Covidence (Melbourne, Victoria, Australia; www.covidence.org). Specifically, we selected studies that included race, ethnic, or cultural-based discrimination as the main exposure or on the pathway and reported a mental health symptom or outcome (clinical diagnosis or assessed mental status/state) among adolescents and adults. Studies related to discrimination based on gender, health status (e.g., body size), or sexual orientation without a racial or ethnic discrimination component and those that did not examine any mental health outcomes or that evaluated mental health delivery services were excluded from the review. Inclusion criteria were met by 171 articles, which were further evaluated for data extraction.

Data Extraction

The following themes emerged upon review of the articles meeting inclusion criteria: methods, stress buffers, intersectionality, life course, and historical trauma. These themes were used to inform the data extraction tool. To assess the studies’ findings, the authors extracted the following data: research questions, study population and location, sample size, study design and methods, exposure, outcome, covariates, type of discrimination and metric, type of mental health disorder and metric, key findings, strengths, limitations, and identified theme(s). During full article review, we identified an additional 25 studies that did not meet the inclusion criteria described above, and the remaining studies (N=171) were categorized into the following themes (numbers are not mutually exclusive) and used in the review summary: 47 methods (out of 80), 30 buffers (out of 48), 13 intersectionality (out of 30), 20 life course (out of 27), 11 historical trauma (out of 42), and 10 without an assigned theme (Table 1).

Table 1.

Empirical studies of the association between discrimination and mental health outcome in the U.S. by racial and ethnic groups

| Themes† | African Americans* | Asians Americans | Latinos/Hispanics | Other Ethnic Groups** | Multiple racial/ethnic groups |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Methods | [15,25,17,9,13] | [73,71,109,22,30,44] | [75,74] | [64,31,99,14,38,82,18] | |

| Mediation | [59,43,46,48,53,83,80] | [24,29,37,50,54] | [33,39,51] | [28] | [55,40,49] |

| Moderation | [83,80,47] | [51,97,41,42] | [62,45] | ||

| Buffer (any) | [59,69,65,72,68,56,63,61,52] | [15,25,17,16,12,70,21,60] | [73,71,109,51,41,42,11,58,91] | [75,74,66] | [64,31,38,55,62,57,10,67] |

| Intersectionality | [61,98] | [73,71,109,44,33,97,41,58,103] | [66] | [31,99,14,101,27,26] | |

| Life course | [43,53,83,80,47,52,20,36,34,77–79,81,76,84,85] | [37,35] | [82,45,67] | ||

| Historical trauma | [46,19] | [25,9,24,60] | [22,30,44,39,11,91] | [28,66,87] | [64,99,38,82,57,67,27,26,89,90] |

The top three themes were identified for each article

Includes African Caribbean living in the US

Jewish, Muslims, North American indigenous, and native Hawaiian in the US

Guiding Conceptual Framework of Discrimination and Mental Health

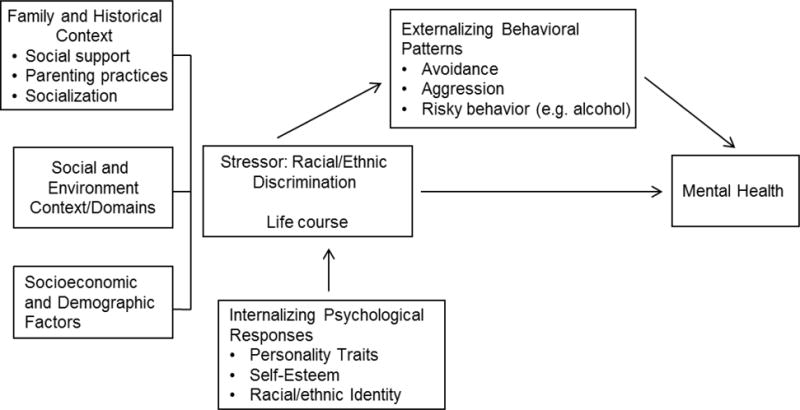

Perceived discrimination has been described as a chronic stressor within various stress and coping frameworks. Drawing from several existing frameworks for the study of discrimination and health, we present a framework to guide this review of the literature (Figure 1). In general, everyone experiences daily stress throughout life. However, it is the persistent and unpredictable nature of exposure to discrimination that can diminish one’s protective psychological resources (e.g., personality) over time; create changes behaviors (e.g., smoking, drug use); and weaken emotional control to increase vulnerability and susceptibility to poor mental health [6]. Mental health also has the potential to impact health behaviors, creating the potential for an adverse cyclical pattern. The family context (e.g., parenting practices) and other demographic variables (e.g., socioeconomic status (SES)) may influence the degree to which the individual perceives the stressor and ultimately how it manifests in affecting mental health.

Figure 1.

Conceptual Framework of Discrimination Stress, Coping and Mental Health

Results

Measurement of Discrimination and Analytic Methods

Discrimination Measures

The 9-item subjective Everyday Discrimination Scale that asks participants to indicate the frequency (0=never, 1=rarely, 2=sometimes, 3=often) with which they experience various forms of mistreatment in their daily lives remains the most commonly used measure in the literature [8]. However, the studies we examined employed this scale in various ways. Some utilized a continuous score based on the sum of all nine responses [9–13], others dichotomized the variable into never and ever discrimination [14], and others averaged the scores of all the items [15–18]. Further, some studies asked participants to specify what they felt was the primary reason for the unfair treatment [11,13,14,18–20], while others did not appear to ask for such specification and examined perceived discrimination in general [9,10,12].

While the Everyday Discrimination Scale was developed for use in African Americans and later adapted for other groups, there are some scales designed for specific groups including: (1) Perceived Discrimination subscale of the Acculturative Stress Scale for International Students [21]; (2) Bicultural Stress Scale among recently immigrated adolescents [22]; (3) the Social, Attitudinal, Familial, and Environmental Acculturation Stress Scale and Intragroup Marginalization Inventory-Family Scale [23]; and (4) the Asian American Racism-Related Stress Inventory [24,25]. Some studies utilized scales to address specific types of harassment in addition to race-based, such as weight-based, SES-based, and sexuality-based [26,27]. A few studies assessed historical trauma as an important factor in elucidating the detrimental impact that long-term and historical exposure to discrimination can have on the mental health status of marginalized racial and ethnic groups. However, the measures of historical trauma used, such as the Historical Loss Scale and Historical Loss Associated Symptoms Scale [28], were developed for Native American populations and may not incorporate concepts that are pertinent to other racial or ethnic groups’ experiences. Additionally, bullying, a form of violence characterized by repeated unprovoked aggressive behavior that intends to cause harm [27,29,30], has been examined among marginalized racial/ethnic adolescents. With the scarcity of racial/ethnic discrimination measures designed specifically for use with adolescents, some studies have examined independently or in addition to questions related to discrimination in the form of “bullying” with metrics such as the Bully Survey [26,27,29–31].

Analytic Methods

Several longitudinal studies were referenced in the articles, but only a few analyzed data using longitudinal methods [18,22,30,32–43]. Overwhelmingly, the findings are based on cross-sectional data. Regression analysis was primarily used, but some employed more sophisticated methods, such as latent class analysis and latent profile analysis to create categories of various exposure variables, including discriminatory experience, cultural stressors, and coping styles [22,28,30,31,44,45]. Techniques were employed by some studies to examine potential intermediary pathways between discrimination and mental health, such as through depressive symptoms or anxiety [19,24,43,46], avoidant coping strategies [33,47], trans diagnostic factors [48], general stress [40], stronger belief in an unjust world [49], acculturation-related and social support variables [13,50,51], anger [46], prosocial behavior [33], and perfectionism [52]. Other studies employed mediation techniques to examine if discrimination was on the pathway between a more upstream exposure, such as childhood adversity [53], historical trauma [28], a perpetual foreigner stereotype [37], white composition of one’s environment [29], critical ethnic awareness [50], and nativity [54], and a mental health outcome. Moderation by stress buffers was also considered in several studies described below.

Buffers: Coping and Personality

Coping strategies or personality traits of individuals and social support networks may mediate or moderate the relationship between discrimination and mental health outcomes (e.g., depression) [55]. Figure 1 depicts these as externalizing behavioral patterns used to cope with discrimination and the internalizing psychological responses to discrimination based on personality traits [56].

Externalizing behavioral patterns

One study found that adolescents exposed to discrimination and who have high levels of depressive symptoms use an avoidance coping response more frequently [31]. Other studies demonstrate that minority youth exposed to discrimination were more likely to engage in nonphysical aggression, aggressive or retaliatory behavior, and drug use [57,58]. Among ethnic minority adults (e.g., Latinos), discrimination has been associated with being a current smoker, substance abuse (e.g., marijuana), and risky sexual behavior [10,11,59–61]. Specifically, Filipino Americans were found to have a two-fold increased probability of alcohol dependence for every one-unit increase in reported unfair treatment due to their ethnicity, speaking a different language, or having an accent [60]. Among African American heterosexual men, risky sexual behaviors have been associated with everyday racial discrimination and post-traumatic stress disorder [59].

Internalizing psychological responses

The effects of discrimination on predicting greater risky behaviors have been shown to vary by individual personal traits, such as tendency for angry rumination [62]. Other personality traits, such as self-esteem, ethnic or racial identity, and spirituality can also influence the response to discrimination [63]. Young adults who reach a high level of ethnic identity maintain high self-esteem and have lower depressive symptoms, even at high levels of discrimination stress [64]. Ethnic identification also moderates the effects of discrimination on alcohol use disorder, indicating that high ethnic identity may mitigate the negative implications of discrimination on mental health and adverse coping behaviors for some ethnic groups [60,65]. However, results are conflicting for Jewish Americans and Latinos. Although ethnic identity predicted higher self-esteem, the moderating effect of ethnic identity on perceived discrimination and depressive symptoms among Jewish Americans indicated that greater ethnic identity was associated greater depression scores in the face of discrimination [66]. Additionally, among Latino men, being a current smoker was more likely for those who had high levels of racial or ethnic identity and experienced everyday discrimination [11].

External supportive buffers

Ethnic socialization has also been found to have a protective role against the adverse effects of discrimination on mental health status through pathways, such as increasing self-esteem, ethnic identity, or bicultural self-efficacy [25,64,67]. Such ethnic socialization and social networks may provide the necessary social and emotional support needed to combat negative internalization of discrimination and poor mental health outcomes [68]. High ethnic social connectedness has been associated with a weakening effect of racial discrimination on post-traumatic stress symptoms in Asian Americans [21]. Moreover, among African Americans adolescents, high emotional support buffered the impact of racial discrimination on biological stress markers (e.g., allostatic load) related to mental health [69].

For Asian Americans, family and spousal support weakened the effects of discrimination/unfair treatment on stress, major depressive disorders, and psychological distress [12,16,17]; whereas, discrimination and low social support have been associated with mental health problems and substance use [70]. Among Latino men, a reduction in the effect of discrimination on suicidal ideation was observed with improved interactions and family relationships [71]. Religious affiliations may also provide support to ethnic minorities facing discrimination. For African Americans, church-based social support moderates the impact of racial discrimination on generalized anxiety disorder [72]. Among Asian Americans and Latinos exposed to discrimination, frequent religious attendance is associated with lower likelihood of major depression [15] and better self-rated mental health [73]. Moreover, Muslim Americans reporting higher levels of spirituality and increased practice of daily prayer show less likelihood of depression despite discrimination [74,75].

Life Course

A life course perspective may be an important lens to examine associations between discrimination and mental health. While much work remains to be done in this arena, studies among youth and young adults may shed light on the importance of discrimination at critical developmental points along the life course. Several studies have shown that adolescents and young adults experiencing racial or ethnic discrimination were at greater risk of depression, anxiety, alcohol and cigarette use, victimization, aggression, violent behaviors, and suicidal ideation [30,36,43,47,52,67,76–83]. Certain groups of adolescents, such as African American boys, appeared to be more frequent targets for racial discrimination as they aged [81]. While these studies indicate that direct experiences of discrimination during adolescence may impact long-term mental health status, parental experiences of discrimination may also be related to child emotional problems via parental depression and parenting practices [84]. These studies of youth and young adults suggest that a complex interplay of childhood adversity, trauma, and experiences of discrimination may influence adult mental health [45,53].

The accumulation of stressors throughout life may have an aggregate impact on mental health. Longitudinal studies during adolescence found an association between increasing frequencies of racism and worse mental health [85]; these studies also found that perceiving being stereotyped as a perpetual foreigner led to increasing perceived discrimination, which in turn led to increased risk of depression over time [37]. Studies of adolescents over time also found that not only may discrimination influence depression, but there may be a feedback loop whereby depression also influences future perceptions of discrimination [35].

Historical Trauma

Research tends to focus on interpersonal level discrimination. Yet, it is the histories of marginalized racial and ethnic in the U.S. that have shaped their experiences of mistreatment over generations. This intergenerational experience of overt and institutionalized oppression (e.g., land loss, enslavement, segregation, genocide, colonization, war, and other forms of social, political, and cultural subjugation) affecting generations of indigenous, African, Asian, Latino, and other marginalized racial and ethnic descendants living in the U.S., is called “historical trauma.” Historical trauma reflects not only the influence this trauma has on those who experience it first-hand, but also its persistent effects on future generations [28,86].

Historical trauma has been conceptualized as a form of unfair treatment with evidence of its contribution to higher prevalence of poor mental health status in marginalized racial and ethnic groups. In a study of reservation-based Native American adolescents and young adults, Brockie et al. [87] found that the odds of depression (aOR=3.74, 95% CI: 1.49–9.41) and PTSD symptoms (aOR=5.60, CI: 2.19–14.30) were significantly higher in those with high versus low levels of historical loss associated symptoms (HLAS; measure of emotional responses related to historical loss, including loss of self-respect, language, culture, and land). Additionally, those who had greater experiences of perceived discrimination had higher odds of PTSD symptoms (aOR=3.01, CI: 1.31–6.88) compared to those with low discrimination. These findings attest to how the history of land loss and culture among Native American populations continues to have a negative impact on the mental health of Native American youth. Further, Mendez et al. [88] found that residential segregation and redlining were associated with reported stress among African American and Latina pregnant women. This highlights how institutionalized policies of segregation may contribute to experiences of stress.

The negative mental health impact of long-term historical trauma in the U.S. is even more evident in examples of the “immigrant paradox.” The “immigrant paradox” describes the phenomenon of poorer health among U.S.-born marginalized racial or ethnic groups than among their foreign-born counterparts, despite the higher SES of U.S.-born groups. Studies show that U.S.-born Asian, African Caribbean, and Latino populations have higher odds of depressive and anxiety symptoms [19,89–91], as well as diagnosed mental disorders and anxiety [9] than their foreign-born counterparts. The Perreira et al. [91] study of adult foreign-born Latinos suggests that immigrants experience increased exposure to stressful conditions, such as discrimination, and may simultaneously lose some of their protective social and culture resources the longer they reside in the U.S., which leads to increased psychological distress. These findings allude to the profound effect that increased residency in the U.S. and perceived discrimination have on mental health. In contrast, studies of Asian American adults have shown that racism-related stress is a significant predictor of mental health status for foreign-born and first-generation U.S. immigrants, but not their U.S.-born counterparts [24,25]. The immediate shock of being treated as a racial or ethnic minority, especially for those who have migrated to the U.S. from more racially or ethnically homogenous populations may result in higher levels of discrimination-based stress. Whereas U.S.-born marginalized racial or ethnic groups may have become immune to the effects of discrimination over time and as a result developed buffers to shield them from the everyday stress of discrimination.

Intersectionality

Marginalized racial or ethnic groups may face discrimination on several fronts beyond their perceived racial or ethnic classification. Discrimination based on gender, SES, age, sexuality, religion, and other identifying factors may lead to racial and ethnic groups experiencing discrimination that is linked to more than one of their identities. This interaction of exposure to multiple forms of discrimination may lead to some groups experiencing a synergistic effect of discrimination that is stronger than the effect of experiencing discrimination based on one identity [92,93]. The concept of intersectionality provides a lens for examining how race, class, gender, and other forms of social identity interact and are perceived to shape people’s health experiences [94,95].

Several studies have examined the intersection of race or ethnicity and gender, specifically, with regards to discrimination. Behnke et al. [96] found that among Latino/a ninth graders, but especially among adolescent girls, there was a significant association between perceived societal discrimination and depressive symptoms. Similarly, results from Piña-Watson et al.’s [97] study of Mexican high school students suggest that gender moderates the relationship between discrimination stress and well-being, with female adolescents experiencing higher levels of somatic symptoms, depressive affect, suicidal ideation, and discrimination stress than their male counterparts. Studies of Asian American, Latina, and African American women have explored how they are exposed to discrimination based on at least two of their social identities (i.e., race and gender), which may negatively influence their mental health outcomes, such as stress [98] and PTSD [99]. Stevens-Watkins et al. [98] insist that it is problematic to exclude the constructs of racism and sexism from the measurement of stressful life events, since they are correlated with one another and with stressful life events. This highlights the importance of examining the intersectionality of social identities in mental health research, and there is a growing body of literature on this topic. Studies have examined SES [100], sexual orientation [101–103], and religious [73] differences in the discrimination-mental health association with findings indicating that marginalized groups have higher odds of poor mental health.

Conclusions

In this review, we sought to address using recent U.S. literature: 1) any methodologic advancements in measuring perceived discrimination; 2) the extent to which theories and/or frameworks have been used in perceived discrimination and mental health research; and 3) the inclusion and analysis of stress buffers. Little improvement in the definition, conceptualization, and measurement of racial and ethnic discrimination as a chronic stressor has occurred. Although only a handful of measures have been used by a majority of studies, there is substantial variation in the use of each measure with an unclear rationale cited for scale selection. Future measurement work should consider the multiple social identities of a person, the social context/domain in which the exposure occurs, how the stressor manifests in adolescents since many of the current measures were developed for adults, and exposure assessment over time. As part of future efforts to improve exposure assessment, the need exists for discrimination scales to reflect the historical traumas experienced by many marginalized racial and ethnic groups.

We positioned this review within a stress and coping framework. However, there are other relevant frameworks, concepts, and theories that were highlighted in this review as important in the study of discrimination and mental health status; these include life course theory, intergenerational effects, intersectionality, and historical trauma. This growing body of literature highlights the destructive consequences of discrimination perceived at different time points throughout the life course, the linkage between parents and child perceptions, and the accumulative stressor and traumatic effect on mental health. Historical trauma is one concept that explains the detrimental impact that long-term and historical exposure to discrimination can have on mental health. Ultimately, it may be important to explore both historical trauma and perceived interpersonal discrimination in order to disentangle the true effect of these constructs on mental health.

Studies of youth and young adults suggest that a complex interplay of childhood adversity, trauma, and experiences of discrimination may influence adult mental health; however further research into the impact of discrimination at different critical periods in the life course and the accumulation of stress due to discrimination throughout life represent an important gap in the current literature. Another important, yet related, gap in the discrimination literature is the need for intergenerational studies. Discrimination experienced across multiple generations may affect health outcomes of future generations as a consequence of accumulated and persistent exposure to stressors and the resulting disruption of physiological systems [104–108]. Consequently, to understand more comprehensively the impact of discrimination on mental health, the intergenerational effect of stress should be taken into account.

Lastly, identifying the buffers that reduce the effects of discrimination on mental health status will help researchers understand why individuals respond differently to discrimination and signal possible areas for intervention. While some individuals display resilience to discrimination, others may turn to adverse health behaviors to cope with the stressor which over time may adversely impact mental health. More studies that investigate the longitudinal effects of buffers on the relationship between discrimination and mental health status are needed. A better understanding on how buffers change throughout the life course will help inform which buffers are most important for adolescent and adult populations. Given the direction of how a person is socialized with regards to their race, ethnicity, and SES, these factors may buffer or enhance the effects of discrimination on mental health status.

Implications for Social Epidemiologic Research

Despite volumes of research spanning decades, gaps remain in our understanding of the factors and mechanisms associated with perceived discrimination and mental health status. This signals an opportunity and a call to social epidemiologists to engage in interdisciplinary research to speed progress in elucidating the effects of racial and ethnic discrimination on mental health. Epidemiology is the science of disease discovery. Hence, there is a need for more emphasis on the development and use of statistical methods to elucidate the various mechanisms that underlie the relationship between discrimination and mental health. With the bulk of the findings based on cross-sectional data, there is a need for more longitudinal studies designed explicitly for the study of discrimination and health. However, longitudinal data of this sort will require more advanced statistical methods such as mediation analysis that has long been used by social scientists. As the call continues for improved measures and defining of the discrimination stress construct, insight can be gleaned from community-based racial equity activists who recognize that while discrimination addresses the unfair nature of the action, many of the current measures do not address the power dynamics inherent in racism or its pervasiveness in institutions. Further, engaging these activists and other stakeholders can inform the critical dimensions of discrimination stress with regards to frequency, appraisal, context/domain, etc. and how this stressor intersects with other identities and personal traits. While this review uncovered little movement in the field, some key future research directions were identified.

Footnotes

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of Interest

Anissa I. Vines, Julia B. Ward, Evette Cordoba, and Kristin Z. Black each declare no potential conflicts of interest.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Contributor Information

Anissa I. Vines, Department of Epidemiology, Gillings School of Global Public Health, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, 266 Rosenau Hall, CB #7435, 135 Dauer Drive, Chapel Hill, NC 27599-7435.

Julia B. Ward, Department of Epidemiology, Gillings School of Global Public Health, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, 135 Dauer Drive, CB #7435, Chapel Hill, NC 27599-7435.

Evette Cordoba, Department of Epidemiology, Gillings School of Global Public Health, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, 135 Dauer Drive, CB #7435, Chapel Hill, NC 27599-7435.

Kristin Z. Black, Department of Health Behavior, Gillings School of Global Public Health, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, 135 Dauer Drive, CB #7440, Chapel Hill, NC 27599-7440.

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as: * Of importance

- 1.Lewis TT, Cogburn CD, Williams DR. Self-Reported Experiences of Discrimination and Health: Scientific Advances, Ongoing Controversies, and Emerging Issues. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2015;11:407–40. doi: 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-032814-112728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Priest N, Paradies Y, Trenerry B, Truong M, Karlsen S, Kelly Y. A systematic review of studies examining the relationship between reported racism and health and wellbeing for children and young people. Soc Sci Med. 2013;95:115–27. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2012.11.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pascoe EA, Smart Richman L. Perceived discrimination and health: a meta-analytic review. Psychol Bull. 2009;135:531–54. doi: 10.1037/a0016059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Priest N, Paradies Y, Trenerry B, Truong M, Karlsen S, Kelly Y. A systematic review of studies examining the relationship between reported racism and health and wellbeing for children and young people. Soc Sci Med. 2013;95:115–27. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2012.11.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pachter LM, Coll CG. Racism and Child Health: A Review of the Literature and Future Directions. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2009;30:255–63. doi: 10.1097/DBP.0b013e3181a7ed5a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pascoe EA, Smart Richman L. Perceived discrimination and health: a meta-analytic review. Psychol Bull. 2009;135:531–54. doi: 10.1037/a0016059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pachter LM, Szalacha LA, Bernstein BA, Garcia Coll C. Perceptions of Racism in Children and Youth (PRaCY): Properties of a self-report instrument for research on children’s health and development. Ethn Heal. 2010;15:33–46. doi: 10.1080/13557850903383196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Williams DR, Yan Yu, Jackson JS, Anderson NB. Racial Differences in Physical and Mental Health: Socioeconomic Status, Stress and Discrimination. J Health Psychol. 1997;2:335–51. doi: 10.1177/135910539700200305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.John DA, de Castro AB, Martin DP, Duran B, Takeuchi DT. Does an immigrant health paradox exist among Asian Americans? Associations of nativity and occupational class with self-rated health and mental disorders. Soc Sci Med. 2012;75:2085–98. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2012.01.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lo CC, Cheng TC. Discrimination’s role in minority groups’ rates of substance-use disorder. Am J Addict. 2012;21:150–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1521-0391.2011.00205.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Molina KM, Jackson B, Rivera-Olmedo N. Discrimination, Racial/Ethnic Identity, and Substance Use Among Latina/os: Are They Gendered? Ann Behav Med. 2016;50:119–29. doi: 10.1007/s12160-015-9738-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mossakowski KN, Zhang W. Does Social Support Buffer the Stress of Discrimination and Reduce Psychological Distress Among Asian Americans? Soc Psychol Q. 2014;77:273–95. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nadimpalli SB, Cleland CM, Hutchinson MK, Islam N, Barnes LL, Van Devanter N. The association between discrimination and the health of Sikh Asian Indians. Heal Psychol. 2016;35:351–5. doi: 10.1037/hea0000268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Reid AE, Rosenthal L, Earnshaw VA, Lewis TT, Lewis JB, Stasko EC, et al. Discrimination and excessive weight gain during pregnancy among Black and Latina young women. Soc Sci Med. 2016;156:134–41. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2016.03.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ai AL, Huang B, Bjorck J, Appel HB. Religious attendance and major depression among Asian Americans from a national database: The mediation of social support. Psycholog Relig Spiritual. 2013;5:78–89. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chae DH, Lee S, Lincoln KD, Ihara ES. Discrimination, family relationships, and major depression among Asian Americans. J Immigr Minor Heal. 2012;14:361–70. doi: 10.1007/s10903-011-9548-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rollock D, Lui PP. Do spouses matter? Discrimination, social support, and psychological distress among asian Americans. Cult Divers Ethn Minor Psychol. 2016;22:47–57. doi: 10.1037/cdp0000045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rosenthal L, Earnshaw VA, Lewis TT, Reid AE, Lewis JB, Stasko EC, et al. Changes in experiences with discrimination across pregnancy and postpartum: age differences and consequences for mental health. Am J Public Heal. 2015;105:686–93. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2014.301906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Clark TT. Perceived discrimination, depressive symptoms, and substance use in young adulthood. Addict Behav. 2014;39:1021–5. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2014.01.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mouzon DM, Taylor RJ, Keith VM, Nicklett EJ, Chatters LM. Discrimination and psychiatric disorders among older African Americans. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2017;32:175–82. doi: 10.1002/gps.4454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wei M, Wang KT, Heppner PP, Du Y. Ethnic and mainstream social connectedness, perceived racial discrimination, and posttraumatic stress symptoms. J Couns Psychol. 2012;59:486–93. doi: 10.1037/a0028000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schwartz SJ, Unger JB, Baezconde-Garbanati L, Zamboanga BL, Lorenzo-Blanco EI, Des Rosiers SE, et al. Trajectories of cultural stressors and effects on mental health and substance use among Hispanic immigrant adolescents. J Adolesc Heal. 2015;56:433–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2014.12.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cano MÁ, de Dios MA, Castro Y, Vaughan EL, Castillo LG, Lorenzo-Blanco EI, et al. Alcohol use severity and depressive symptoms among late adolescent Hispanics: Testing associations of acculturation and enculturation in a bicultural transaction model. Addict Behav. 2015;49:78–82. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2015.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liu CM, Suyemoto KL. The effects of racism-related stress on Asian Americans: Anxiety and depression among different generational statuses. Asian Am J Psychol. 2016;7:137–46. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Miller MJ, Yang M, Farrell JA, Lin LL. Racial and Cultural Factors Affecting the Mental Health of Asian Americans. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 2011;81:489–97. doi: 10.1111/j.1939-0025.2011.01118.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bucchianeri MM, Eisenberg ME, Wall MM, Piran N, Neumark-Sztainer D. Multiple types of harassment: associations with emotional well-being and unhealthy behaviors in adolescents. J Adolesc Heal. 2014;54:724–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2013.10.205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hightow-Weidman LB, Phillips G, Jones KC, Outlaw AY, Fields SD, Smith JC. Racial and sexual identity-related maltreatment among minority YMSM: Prevalence, perceptions, and the association with emotional distress. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2011;25:S39–45. doi: 10.1089/apc.2011.9877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pokhrel P, Herzog TA. Historical trauma and substance use among Native Hawaiian college students. Am J Heal Behav. 2014;38:420–9. doi: 10.5993/AJHB.38.3.11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shin JY, D’Antonio E, Son H, Kim SA, Park Y. Bullying and discrimination experiences among Korean-American adolescents. J Adolesc. 2011;34:873–83. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2011.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lorenzo-Blanco EI, Unger JB, Oshri A, Baezconde-Garbanati L, Soto D. Profiles of bullying victimization, discrimination, social support, and school safety: Links with Latino/a youth acculturation, gender, depressive symptoms, and cigarette use. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 2016;86:37–48. doi: 10.1037/ort0000113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Garnett BR, Masyn KE, Austin SB, Williams DR, Viswanath K. Coping styles of adolescents experiencing multiple forms of discrimination and bullying: evidence from a sample of ethnically diverse urban youth. J Sch Heal. 2015;85:109–17. doi: 10.1111/josh.12225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cheng HL, Mallinckrodt B. Racial/ethnic discrimination, posttraumatic stress symptoms, and alcohol problems in a longitudinal study of Hispanic/Latino college students. J Couns Psychol. 2015;62:38–49. doi: 10.1037/cou0000052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Davis AN, Carlo G, Schwartz SJ, Unger JB, Zamboanga BL, Lorenzo-Blanco EI, et al. The Longitudinal Associations Between Discrimination, Depressive Symptoms, and Prosocial Behaviors in U.S. Latino/a Recent Immigrant Adolescents. J Youth Adolesc. 2016;45:457–70. doi: 10.1007/s10964-015-0394-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ford KR, Hurd NM, Jagers RJ, Sellers RM. Caregiver experiences of discrimination and african american adolescents’ psychological health over time. Child Dev. 2013;84:485–99. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2012.01864.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hou Y, Kim SY, Wang Y, Shen Y, Orozco-Lapray D. Longitudinal Reciprocal Relationships Between Discrimination and Ethnic Affect or Depressive Symptoms Among Chinese American Adolescents. J Youth Adolesc. 2015;44:2110–21. doi: 10.1007/s10964-015-0300-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hurd NM, Varner FA, Caldwell CH, Zimmerman MA. Does perceived racial discrimination predict changes in psychological distress and substance use over time? An examination among Black emerging adults. Dev Psychol. 2014;50:1910–8. doi: 10.1037/a0036438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kim SY, Wang Y, Deng S, Alvarez R, Li J. Accent, perpetual foreigner stereotype, and perceived discrimination as indirect links between English proficiency and depressive symptoms in Chinese American adolescents. Dev Psychol. 2011;47:289–301. doi: 10.1037/a0020712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lipsky S, Kernic MA, Qiu Q, Hasin DS. Posttraumatic stress disorder and alcohol misuse among women: effects of ethnic minority stressors. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2016;51:407–19. doi: 10.1007/s00127-015-1109-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39*.Lorenzo-Blanco EI, Meca A, Unger JB, Romero A, Gonzales-Backen M, Pina-Watson B, et al. Latino parent acculturation stress: Longitudinal effects on family functioning and youth emotional and behavioral health. J Fam Psychol. 2016;30:966–76. doi: 10.1037/fam0000223. This study utilizes novel methods such as latent profile analysis to examine profiles of community experience that varied by gender and acculturation. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Luo Y, Xu J, Granberg E, Wentworth WM. A longitudinal study of social status, perceived discrimination, and physical and emotional health among older adults. Res Aging. 2012;34:275–301. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nair RL, White RM, Roosa MW, Zeiders KH. Cultural stressors and mental health symptoms among Mexican Americans: a prospective study examining the impact of the family and neighborhood context. J Youth Adolesc. 2013;42:1611–23. doi: 10.1007/s10964-012-9834-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Toomey RB, Umaña-Taylor AJ, Updegraff KA, Jahromi LB. Ethnic identity development and ethnic discrimination: Examining longitudinal associations with adjustment for Mexican-origin adolescent mothers. J Adolesc. 2013;36:825–33. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2013.06.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Walker R, Francis D, Brody G, Simons R, Cutrona C, Gibbons F. A Longitudinal Study of Racial Discrimination and Risk for Death Ideation in African American Youth. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2017;47:86–102. doi: 10.1111/sltb.12251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cano MÁ, Schwartz SJ, Castillo LG, Romero AJ, Huang S, Lorenzo-Blanco EI, et al. Depressive symptoms and externalizing behaviors among hispanic immigrant adolescents: Examining longitudinal effects of cultural stress. J Adolesc. 2015;42:31–9. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2015.03.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45*.Myers HF, Wyatt GE, Ullman JB, Loeb TB, Chin D, Prause N, et al. Cumulative burden of lifetime adversities: Trauma and mental health in low-SES African Americans and Latino/as. Psychol Trauma. 2015;7:243–51. doi: 10.1037/a0039077. This article contributes to the literature regarding the impacts of life course discrimination on mental health. The article provides a good overview of lifetime adversities and traumas and their relations to mental health. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Boynton MH, O’Hara RE, Covault J, Scott D, Tennen H. A mediational model of racial discrimination and alcohol-related problems among african american college students. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2014;75:228–34. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2014.75.228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Seaton EK, Douglass S. School diversity and racial discrimination among African-American adolescents. Cult Divers Ethn Minor Psychol. 2014;20:156–65. doi: 10.1037/a0035322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48*.Rodriguez-Seijas C, Stohl M, Hasin DS, Eaton NR. Transdiagnostic Factors and Mediation of the Relationship Between Perceived Racial Discrimination and Mental Disorders. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72:706–13. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2015.0148. This study utilizes latent variable measurement models, including factor analysis, and indirect effect models, to examine if transdiagnostic factors mediate the effects of discrimination on several mental disorders among a nationally representative sample (N = 5191) of African American and Afro-Caribbean adults in the United States. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Liang CTH, Borders A. Beliefs in an unjust world mediate the associations between perceived ethnic discrimination and psychological functioning. Pers Individ Dif. 2012;53:528–33. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kim I. The role of critical ethnic awareness and social support in the discrimination-depression relationship among Asian Americans: path analysis. Cult Divers Ethn Minor Psychol. 2014;20:52–60. doi: 10.1037/a0034529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Shell AM, Peek MK, Eschbach K. Neighborhood Hispanic composition and depressive symptoms among Mexican-descent residents of Texas City. Texas Soc Sci Med. 2013;99:56–63. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.10.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lambert SF, Robinson WL, Ialongo NS. The role of socially prescribed perfectionism in the link between perceived racial discrimination and African American adolescents’ depressive symptoms. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 2014;42:577–87. doi: 10.1007/s10802-013-9814-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Allen VC, Myers HF, Williams JK. Depression among Black bisexual men with early and later life adversities. Cult Divers Ethn Minor Psychol. 2014;20:128–37. doi: 10.1037/a0034128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lau AS, Tsai W, Shih J, Liu LL, Hwang WC, Takeuchi DT. The immigrant paradox among Asian American women: Are disparities in the burden of depression and anxiety paradoxical or explicable. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2013;81:901–11. doi: 10.1037/a0032105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Borders A, Liang CTH. Rumination partially mediates the associations between perceived ethnic discrimination, emotional distress, and aggression. Cult Divers Ethn Minor Psychol. 2011;17:125–33. doi: 10.1037/a0023357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Gibbons FX, Kingsbury JH, Weng CY, Gerrard M, Cutrona C, Wills TA, et al. Effects of perceived racial discrimination on health status and health behavior: a differential mediation hypothesis. Heal Psychol. 2014;33:11–9. doi: 10.1037/a0033857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bogart LM, Elliott MN, Kanouse DE, Klein DJ, Davies SL, Cuccaro PM, et al. Association between perceived discrimination and racial/ethnic disparities in problem behaviors among preadolescent youths. Am J Public Heal. 2013;103:1074–81. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.301073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58*.Basanez T, Unger JB, Soto D, Crano W, Baezconde-Garbanati L. Perceived discrimination as a risk factor for depressive symptoms and substance use among Hispanic adolescents in Los Angeles. Ethn Heal. 2013;18:244–61. doi: 10.1080/13557858.2012.713093. This was a longitundial study design. Additionally, a neighborhood analysis (ethnic composition) effect on the discrimination and drug use was assessed. More neighborhood assessment in this field is needed. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Bowleg L, Fitz CC, Burkholder GJ, Massie JS, Wahome R, Teti M, et al. Racial discrimination and posttraumatic stress symptoms as pathways to sexual HIV risk behaviors among urban Black heterosexual men. AIDS Care. 2014;26:1050–7. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2014.906548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Iwamoto DK, Kaya A, Grivel M, Clinton L. Under-Researched Demographics: Heavy Episodic Drinking and Alcohol-Related Problems Among Asian Americans. Alcohol Res. 2016;38:17–25. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Thoma BC, Huebner DM. Health consequences of racist and antigay discrimination for multiple minority adolescents. Cult Divers Ethn Minor Psychol. 2013;19:404–13. doi: 10.1037/a0031739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62*.Borders A, Hennebry KA. Angry rumination moderates the association between perceived ethnic discrimination and risky behaviors. Pers Individ Dif. 2015;79:81–6. Mediation analysis was conducted to assess individual personality traits on the discrimination and psychological distress relationship. Mediation analysis is important to understand pathways that explain this association. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hughes M, Kiecolt KJ, Keith VM, Demo DH. Racial identity and well-being among African Americans. Soc Psychol Q. 2015;78:25–48. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Romero AJ, Edwards LM, Fryberg SA, Orduña M. Resilience to discrimination stress across ethnic identity stages of development. J Appl Soc Psychol. 2014;44:1–11. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Chae DH, Lincoln KD, Jackson JS. Discrimination, Attribution, and Racial Group Identification: Implications for Psychological Distress Among Black Americans in the National Survey of American Life (2001–2003) Am J Orthopsychiatry. 2011;81:498–506. doi: 10.1111/j.1939-0025.2011.01122.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Weisskirch RS, Kim SY, Schwartz SJ, Whitbourne SK. The complexity of ethnic identity among Jewish American emerging adults. Identity An Int. J Theory Res. 2016;16:127–41. doi: 10.1080/15283488.2016.1190724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67*.Arnold T, Braje SE, Kawahara D, Shuman T. Ethnic socialization, perceived discrimination, and psychological adjustment among transracially adopted and nonadopted ethnic minority adults. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 2016;86:540–51. doi: 10.1037/ort0000172. This study has a life course component that will be important to move the field forward. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Marshall GL, Rue TC. Perceived discrimination and social networks among older African Americans and Caribbean blacks. Fam Community Heal. 2012;35:300–11. doi: 10.1097/FCH.0b013e318266660f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69*.Brody GH, Lei M, Chae DH, Yu T, Kogan SM, Beach SRH. Perceived discrimination among African American adolescents and allostatic load: A longitudinal analysis with buffering effects. Child Dev. 2014;85:989–1002. doi: 10.1111/cdev.12213. This study has a life course component that will be important to move the field forward. Also includes a biological component (allostatic load) to explore potential biological mechansims related to discrimination exposure. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Tsai JH, Thompson EA. Impact of social discrimination, job concerns, and social support on Filipino immigrant worker mental health and substance use. Am J Ind Med. 2013;56:1082–94. doi: 10.1002/ajim.22223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Ai AL, Pappas C, Simonsen E. Risk and protective factors for three major mental health problems among Latino American men nationwide. Am J Mens Heal. 2015;9:64–75. doi: 10.1177/1557988314528533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Graham JR, Roemer L. A preliminary study of the moderating role of church-based social support in the relationship between racist experiences and general anxiety symptoms. Cult Divers Ethn Minor Psychol. 2012;18:268–76. doi: 10.1037/a0028695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Ai AL, Aisenberg E, Weiss SI, Salazar D. Racial/ethnic identity and subjective physical and mental health of Latino Americans: an asset within? Am J Community Psychol. 2014;53:173–84. doi: 10.1007/s10464-014-9635-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Hodge DR, Zidan T, Husain A. Depression among Muslims in the United States: Examining the Role of Discrimination and Spirituality as Risk and Protective Factors. Soc Work. 2016;61:45–52. doi: 10.1093/sw/swv055. investigates direct discrimination (eg. offensive names) as oppose to perceived discrimination based on cultural relevant practces with being Muslim.This may be a growing area of interest given today’s political events. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Hodge DR, Zidan T, Husain A. Modeling the relationships between discrimination, depression, substance use, and spirituality with Muslims in the United States. Soc Work Res. 2015;39:223–33. [Google Scholar]

- 76*.English D, Lambert SF, Ialongo NS. Longitudinal associations between experienced racial discrimination and depressive symptoms in African American adolescents. Dev Psychol. 2014;50:1190–6. doi: 10.1037/a0034703. This article is a longitudinal study that contributes to the life course literature. It also provides a good overview of models of racial discrimination effects and the potential modifying role of sex. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Estrada-Martinez LM, Caldwell CH, Bauermeister JA, Zimmerman MA. Stressors in multiple life-domains and the risk for externalizing and internalizing behaviors among African Americans during emerging adulthood. J Youth Adolesc. 2012;41:1600–12. doi: 10.1007/s10964-012-9778-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Kogan SM, Yu T, Allen KA, Brody GH. Racial microstressors, racial self-concept, and depressive symptoms among male African Americans during the transition to adulthood. J Youth Adolesc. 2015;44:898–909. doi: 10.1007/s10964-014-0199-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Sanders-Phillips K, Kliewer W, Tirmazi T, Nebbitt V, Carter T, Key H. Perceived racial discrimination, drug use, and psychological distress in African American youth: A pathway to child health disparities. J Soc Issues. 2014;70:279–97. [Google Scholar]

- 80.Seaton EK, Upton R, Gilbert A, Volpe V. A moderated mediation model: Racial discrimination, coping strategies, and racial identity among Black adolescents. Child Dev. 2014;85:882–90. doi: 10.1111/cdev.12122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Smith-Bynum MA, Lambert SF, English D, Ialongo NS. Associations between trajectories of perceived racial discrimination and psychological symptoms among African American adolescents. Dev Psychopathol. 2014;26:1049–65. doi: 10.1017/S0954579414000571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Tobler AL, Maldonado-Molina MM, Staras SA, O’Mara RJ, Livingston MD, Komro KA. Perceived racial/ethnic discrimination, problem behaviors, and mental health among minority urban youth. Ethn Heal. 2013;18:337–49. doi: 10.1080/13557858.2012.730609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Walker RL, Salami TK, Carter SE, Flowers K. Perceived racism and suicide ideation: mediating role of depression but moderating role of religiosity among African American adults. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2014;44:548–59. doi: 10.1111/sltb.12089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Anderson RE, Hussain SB, Wilson MN, Shaw DS, Dishion TJ, Williams JL. Pathways to pain: Racial discrimination and relations between parental functioning and child psychosocial well-being. J Black Psychol. 2015;41:491–512. doi: 10.1177/0095798414548511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Kwate NO, Goodman MS. Cross-sectional and longitudinal effects of racism on mental health among residents of Black neighborhoods in New York City. Am J Public Heal. 2015;105:711–8. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2014.302243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Sotero M. A Conceptual Model of Historical Trauma: Implications for Public Health Practice and Research. J Health Dispar Res Pract. 2006;1:93–108. [Google Scholar]

- 87*.Brockie TN, Dana-Sacco G, Wallen GR, Wilcox HC, Campbell JC. The Relationship of Adverse Childhood Experiences to PTSD, Depression, Poly-Drug Use and Suicide Attempt in Reservation-Based Native American Adolescents and Young Adults. Am J Community Psychol. 2015;55:411–21. doi: 10.1007/s10464-015-9721-3. This study examined how historical loss associated symptoms (HLAS) and perceived discrimination are associated with risk behaviors (e.g., poly-drug use, suicidal attempt) and mental health outcomes (e.g., depression symptoms, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD)) in a sample of 288 Native American youth tribal members ages 15–24. All of the survey measures (except for the Short Form for PTSD) have been used and validated in Native American communities. They examined two culturally specific variables for discrimination (i.e., HLAS and perceived discrimination). They found that the odds of depression, poly-drug use, and PTSD were strongly and significantly higher in those with higher compared to low levels of HLAS. Also, those who had experienced greater experiences of discrimination had higher odds of poly-drug use and PTSD compared to those with low discrimination. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Mendez DD, Hogan VK, Culhane JF. Stress during pregnancy: The role of institutional racism. Stress Heal. 2013;29:266–74. doi: 10.1002/smi.2462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Budhwani H, Hearld KR, Chavez-Yenter D. Depression in Racial and Ethnic Minorities: the Impact of Nativity and Discrimination. J Racial Ethn Heal Disparities. 2015;2:34–42. doi: 10.1007/s40615-014-0045-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Budhwani H, Hearld KR, Chavez-Yenter D. Generalized anxiety disorder in racial and ethnic minorities: a case of nativity and contextual factors. J Affect Disord. 2015;175:275–80. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2015.01.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91*.Perreira KM, Gotman N, Isasi CR, Arguelles W, Castaneda SF, Daviglus ML, et al. Mental Health and Exposure to the United States: Key Correlates from the Hispanic Community Health Study of Latinos. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2015;203:670–8. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0000000000000350. This study examined the association between exposure to the United States and poor mental health in 15,004 adult foreign-born Hispanics/Latinos as part of the Hispanic Community Health Study of Latinos. Participants were recruited from 2010 Census block groups (in the Bronx, Chicago, Miami, and San Diego) using a two-stage household probability design. They found that compared to their U.S.-born counterparts, Hispanic/Latino immigrants with 21 or more years of U.S. residency had significantly higher odds of psychological distress; whereas, immigrants with fewer than 10 years of residency had significantly lower odds of depressive or anxiety symptoms. These findings suggest that immigrants experience increased exposure to stressful conditions, such as discrimination, and may simultaneously lose some of their protective social and culture resources the longer they reside in the U.S., which in turn leads to increased psychological distress. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Weber L. Reconstructing the landscape of health disparities research: promoting dialogue and collaboration between feminist intersectional and biomedical paradigms. In: Shulz A, Mullings L, editors. Gender, Race, Class, Heal Intersect Approaches. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 2006. pp. 21–59. [Google Scholar]

- 93.Hogan VK, Rowley D, Bennett T, Taylor KD. Life course, social determinants, and health inequities: Toward a national plan for achieving health equity for African American infants-a concept paper. Matern Child Health J. 2012;16:1143–50. doi: 10.1007/s10995-011-0847-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Bowleg L. The problem with the phrase women and minorities: intersectionality-an important theoretical framework for public health. Am J Public Health. 2012;102:1267–73. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.300750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Kelly UA. Integrating intersectionality and biomedicine in health disparities research. Adv Nurs Sci. 2009;32:E42–56. doi: 10.1097/ANS.0b013e3181a3b3fc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Behnke AO, Plunkett SW, Sands T, Bámaca-Colbert MY. J Cross Cult Psychol. Vol. 42. Thousand Oaks, California: Sage Publications Inc; 2011. The Relationship Between Latino Adolescents’ Perceptions of Discrimination, Neighborhood Risk, and Parenting on Self-Esteem and Depressive Symptoms; pp. 1179–97. [Google Scholar]

- 97.Piña-Watson B, Dornhecker M, Salinas SR. The impact of bicultural stress on Mexican American adolescents’ depressive symptoms and suicidal ideation: Gender matters. Hisp J Behav Sci. 2015;37:342–64. [Google Scholar]

- 98.Stevens-Watkins D, Perry B, Pullen E, Jewell J, Oser CB. Examining the associations of racism, sexism, and stressful life events on psychological distress among African-American women. Cult Divers Ethn Minor Psychol. 2014;20:561–9. doi: 10.1037/a0036700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Pilver CE, Desai R, Kasl S, Levy BR. Lifetime discrimination associated with greater likelihood of premenstrual dysphoric disorder. J Women’s Heal. 2011;20:923–31. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2010.2456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Krieger N, Kaddour A, Koenen K, Kosheleva A, Chen JT, Waterman PD, et al. Occupational, social, and relationship hazards and psychological distress among low-income workers: Implications of the “inverse hazard law”. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2011;65:260–72. doi: 10.1136/jech.2009.087387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Choi KH, Paul J, Ayala G, Boylan R, Gregorich SE. Experiences of discrimination and their impact on the mental health among African American, Asian and Pacific Islander, and Latino men who have sex with men. Am J Public Heal. 2013;103:868–74. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.301052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Bostwick WB, Boyd CJ, Hughes TL, West BT, McCabe SE. Discrimination and mental health among lesbian, gay, and bisexual adults in the United States. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 2014;84:35–45. doi: 10.1037/h0098851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Reisen CA, Brooks KD, Zea MC, Poppen PJ, Bianchi FT. Can additive measures add to an intersectional understanding? Experiences of gay and ethnic discrimination among HIV-positive Latino gay men. Cult Divers Ethn Minor Psychol. 2013;19:208–17. doi: 10.1037/a0031906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Chrousos GP, Gold PW. The concepts of stress and stress system disorders. Overview of physical and behavioral homeostasis. JAMA. 1992;267:1244–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Ehlert U, Gaab J, Heinrichs M. Psychoneuroendocrinological contributions to the etiology of depression, posttraumatic stress disorder, and stress-related bodily disorders: the role of the hypothalamus-pituitary-adrenal axis. Biol Psychol. 2001;57:141–52. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0511(01)00092-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Tafet GE, Bernardini R. Psychoneuroendocrinological links between chronic stress and depression. Prog. Neuropsychopharmacol. Biol Psychiatry. 2003;27:893–903. doi: 10.1016/S0278-5846(03)00162-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Vyas A, Pillai AG, Chattarji S. Recovery after chronic stress fails to reverse amygdaloid neuronal hypertrophy and enhanced anxiety-like behavior. Neuroscience. 2004;128:667–73. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2004.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Drevets WC. Neuroimaging and neuropathological studies of depression: implications for the cognitive-emotional features of mood disorders. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2001;11:240–9. doi: 10.1016/s0959-4388(00)00203-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Behnke AO, Plunkett SW, Sands T, Bámaca-Colbert MY. The Relationship Between Latino Adolescents’ Perceptions of Discrimination, Neighborhood Risk, and Parenting on Self-Esteem and Depressive Symptoms. J Cross Cult Psychol. 2011;42:1179–97. [Google Scholar]