Abstract

Background:

Oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC) is the tenth most common cancer in the world. The diagnosis of OSCC remains problematic, especially in advanced-stage tumors.

Aims:

The present study was conducted to understand the pattern of expression of paxillin in varying grades of carcinomas and also to ascertain whether its expression has an association with increasing grades.

Methods:

A total of ninety formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tissues of OSCC were included in the study comprising thirty cases of each of well-differentiated squamous cell carcinomas, moderately differentiated squamous cell carcinomas (MDSCCs) and poorly differentiated squamous cell carcinomas (PDSCCs). The tissue sections were subjected to immunohistochemical staining of paxillin using super polymer-sensitive polymer 3,3’ diaminobenzidine detection kit. All the three groups were analyzed on various parameters including staining intensity, location and percentage of staining. SPSS 19.0 was used to analyze the data.

Results:

Paxillin stain positivity was observed in 95.5% of the cases. Predominant intense paxillin staining was demonstrated in 17 (56.6%) cases of well-differentiated squamous cell carcinoma, 28 (93.3%) cases of moderately differentiated squamous squamous cell carcinoma and 15 (50%) cases of PDSCC. A predominant cytoplasmic staining was observed in 21 (70%) cases of PDSCC and cytoplasmic plus membrane staining in 14 (46.6%) cases of MDSCC.

Conclusion:

The present study provides evidence that paxillin may be involved in the development and progression of OSCC. Thus, paxillin could be considered a useful biomarker for patient management and prognosis.

Keywords: Biomarker, oral squamous cell carcinoma, paxillin

INTRODUCTION

Oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC) is the tenth most common cancer in the world.[1] The diagnosis of OSCC remains problematic, especially in advanced-stage tumors. The metastasis of OSCC is a complex process and is the major cause of cancer deaths. Although there is an availability of tests for early diagnosis, prognosis prediction and novel therapeutic strategies for OSCC, the 5-year survival rate is still low and there is a necessity to identify valuable biomarkers.[1]

Paxillin is an adapter or scaffold protein, which helps in recruiting diverse cytoskeleton and signaling proteins into a complex and directs downstream signal transmission. It is a multidomain protein and localizes specifically to the cell adhesion sites of the extracellular matrix called focal adhesions. Paxillin actively links actin filaments to integrin-rich cell adhesion sites. The primary function of the paxillin is to act as a molecular adapter or scaffold protein aiding in implementing changes in the organization of actin cytoskeleton, which are important for cell motility associated with metastasis of the tumor.

Various paxillin-binding proteins have oncogenic equivalents, such as v-Src, v-Crk and Bcr-Abl. These proteins may use paxillin both as a substrate and as a docking site to bypass the normal adhesion and the growth factor signaling cascades required to control cell proliferation.[2] Paxillin also plays a role in cell proliferation, survival and angiogenesis.[3] The expression of paxillin promotes the tumor progression and metastasis of laryngeal carcinoma,[4] salivary adenoid cystic carcinoma,[5] prostate carcinoma,[6] lung carcinoma,[7] human breast cancer,[8] colorectal cancer[9] and Kaposi's carcinoma,[10] in which the overexpression is associated with lymph node metastases, advanced stage, decreased survival and poor prognosis.

However, the expression of paxillin in the histological differentiation of OSCC is not studied. Hence, this study was intended to evaluate and compare the expression of paxillin in different grades of OSCC.

METHODS

In this retrospective study, tissue blocks of OSCC samples were retrieved from the archives of department of oral pathology and microbiology. A total of ninety formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tissues (FFPE) of OSCC were included in the study comprising thirty cases of each of well-differentiated squamous cell carcinoma (WDSCC), moderately differentiated squamous cell carcinoma (MDSCC) and poorly differentiated squamous cell carcinoma (PDSCC). The sample size was calculated based on the reported proportion of positivity (expression levels) in previous articles by Shi et al.[5]

Standard H&E staining method and immunostaining with antibody against paxillin were used in the study. FFPE 4-μm sections were coated with 3-(aminopropyl) triethoxysilane and deparaffinization was performed. The slides having tissue sections were treated two times with xylene for approximately 10 min each to remove paraffin and with alcohol for 5 min each to dehydrate the tissue. To retrieve the heat-induced epitope, the slides were filled with citrate buffer and placed in an antigen retriever system. Two cycles of 12 min at 96°C were set. A staining trough containing slides was gently taken out when the cycles were complete and cooled until it attained the room temperature. The slides were washed in tris-buffered saline (TBS) for 5 min.

The slides were treated with hydrogen peroxide to block endogenous peroxidase activity and then incubated with primary monoclonal antibody against paxillin protein (monoclonal rabbit anti-paxillin clone Y113) for 1 h in a humidifying chamber. The slides were then washed with wash buffer for 5 min. To promote the Ag-Ab reaction, super enhancer was added and incubated for 20 min followed by two changes of TBS for 5 min each. Slides were then incubated with poly horseradish peroxidase for 30 min followed by two changes of TBS for 5 min each.

Slides were incubated with freshly prepared substrate-chromogen solution for 10 min. Solution was prepared by mixing 25 μL of concentrated 3,3’ diaminobenzidine in 500 μL of substrate buffer for ten slides. This step enables visualization of antigen–antibody reaction.

Harris hematoxylin was used to counterstain the slides for 1 min. The slides were then dehydrated and mounted with DPx.[11] Location, intensity and percentage of staining were analyzed and scored.[12]

The criteria used to define the percentage of positive cells with paxillin expression were set. Percentage staining score of 0 was considered to be negative reaction, 1 was given for 1%–25% positive reaction, 2 for 26%–50% positive reaction and 3 was given for ≥50% positive reaction. Furthermore, the criteria used to define intensity were set. The intensity score of 0 was considered to be absence of staining, 1 was considered to be mild staining and 2 was considered to be intense staining. Similarly, the criteria used to define location were also fixed. The location score of 1 was considered to be cytoplasmic and 2 was considered to be cytoplasmic + membrane. SPSS software version 19.0 (California state university, Northridge, USA) was used to analyze the data. Chi-square test was used to analyze the association of the intensity, location and percentage of positivity with different study groups.

RESULTS

The present study was conducted to determine the expression of paxillin among different grades of OSCC. A total of ninety biopsy specimens of OSCC were stained using paxillin antibody and analyzed. Paxillin stain positivity was observed in 95.5% of the cases. Among the study groups, WDSCC demonstrated stain positivity in 29 (96.6%) cases, MDSCC showed stain positivity in 30 (100%) cases, while PDSCC demonstrated stain positivity in 27 (90%) cases.

MDSCC demonstrated both predominant intense staining and also a very minimal mild staining. One case of WDSCC and three cases of PDSCC demonstrated absence of staining. A statistically significant difference in intensity was observed between the groups WDSCC versus MDSCC (P = 0.004) and between MDSCC versus PDSCC (P = 0.0008).

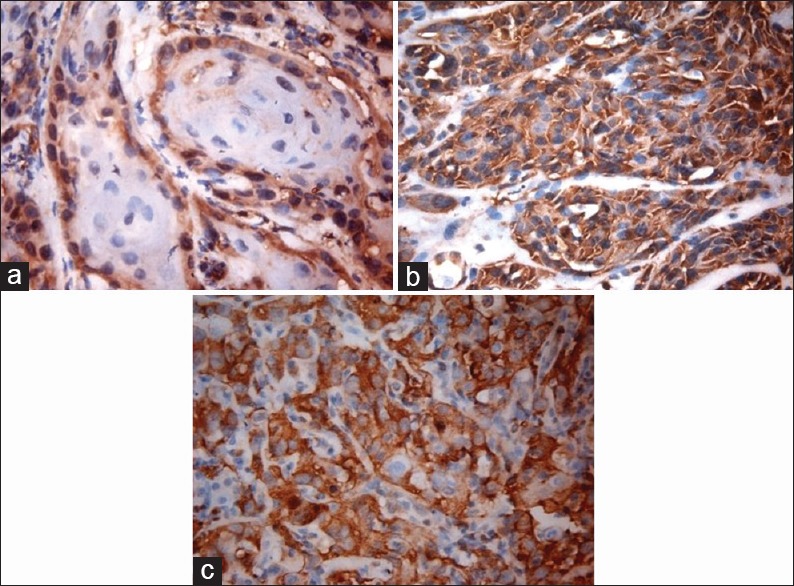

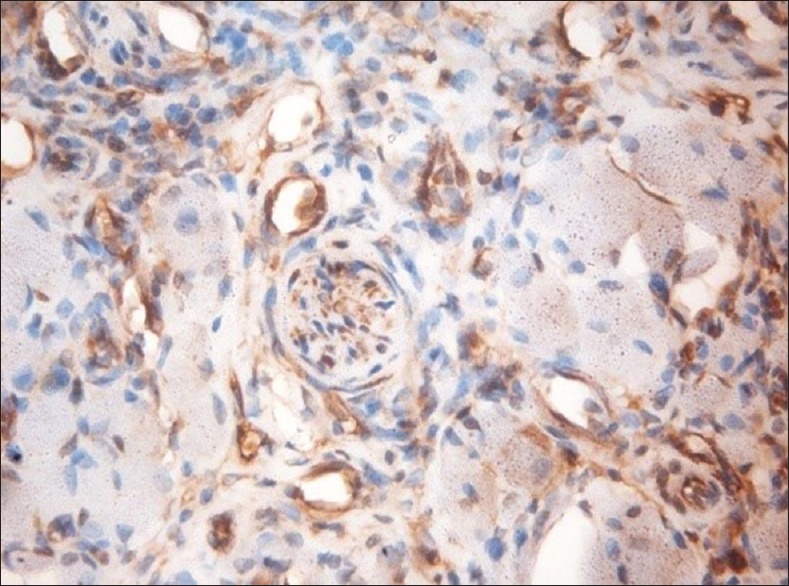

Based on the absence of the staining (0), cytoplasmic (1, C) staining and combined cytoplasmic and membrane (2, C + M) staining, the location of the paxillin was assessed. Cytoplasmic staining was predominant in 21 (70%) cases of PDSCC grade and cytoplasmic + membrane staining was maximum in 15 (50%) cases of WDSCC grade. However, 16 (53.3%) cases showed cytoplasmic and 14 (46.6%) cases showed cytoplasmic and membrane staining in MDSCC grade [Figure 1]. Absence of staining was observed in 1 (3.3%) case of WDSCC and in 3 (3.3%) cases of PDSCC grade. On intergroup comparison, WDSCC versus PDSCC (P = 0.04) and MDSCC versus PDSCC (P = 0.0321) demonstrated a significant difference. Cytoplasmic staining showed a statistically significant increase with decrease in the grade of differentiation (P = 0.041).

Figure 1.

High power view of well-differentiated (a), moderately differentiated, ×40 (b) and poorly differentiated, ×40 (c) squamous cell carcinoma showing intense paxillin staining, ×40

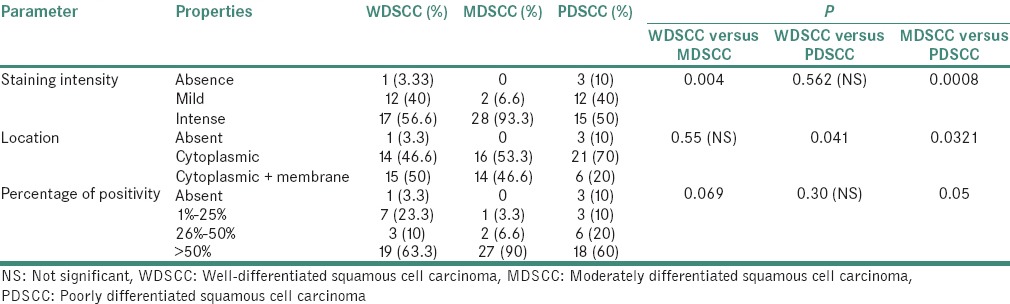

When the percentage differences of paxillin immunohistochemical staining were studied, >50% positivity for immunostaining was demonstrated in majority of the cases, that is, 27 (90%). An increased percentage of positivity with increasing grade was observed (WDSCC demonstrated positivity in 19 [63.3%] cases). On intergroup analysis, a statistically significant difference was observed between MDSCC and PDSCC (P = 0.05) groups [Table 1].

Table 1.

Comparison of intensity, localization and percentage of staining within various groups

DISCUSSION

In the present study, OSCC samples had increased expression of paxillin protein in all the three groups, which suggested the crucial role of paxillin in oral carcinogenesis. The expression observed in the present study was marginally higher than that reported in studies of colorectal cancer (80%),[12] lung adenocarcinoma (69%)[7] and breast carcinoma (80%).[8] This could possibly be due to the important role of paxillin in OSCC and its pathogenesis. However, another study by Vadlamudi et al. revealed a strong association of coexpression of the human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2)/HER3 receptors with paxillin in breast cancer cell line.[8]

In the present study, a progressive increase of paxillin expression in WDSCC and MDSCC and a reduction in PDSCC were observed. A similar study conducted by Panousis et al. reported the adhesive role of paxillin in less aggressive neoplasms when compared to aggressive phenotypes. The study suggested that paxillin overexpression may be associated with less aggressive phenotype, and a decrease in expression with increased grade of differentiation was noticed.[13]

When the intensity of the staining was evaluated among the study groups, an intense paxillin staining was reported in all the three groups. Although most of the studies have not studied the intensities alone, they have reported the percentage and score of intensity. Increase in the intensity of staining was consistent with the studies, which were conducted on breast,[8] colorectal[9] and gastric carcinomas.[12] The low levels and absence of staining, which were observed in PDSCC, and the predominant intense staining in MDSCC, were consistent with the reports of certain human lung cancers and liver metastasis.[14] The increased adhesion ability is suggested to be associated with the paxillin overexpression and its function in downregulation in tumor cell suppression and enhancing the survival.

When the location of the paxillin was assessed, a significant increase was observed in the percentage of cytoplasmic staining with decrease in the grade of differentiation (P = 0.041). A study conducted by Shi et al.[5] showed the upregulation of paxillin expression in salivary adenoid cystic carcinoma while cytoplasmic staining was recognized in 57% of salivary adenoid cystic carcinoma, which was significantly associated with clinical stage and metastasis (P < 0.05). The membrane staining reported in the present study was similar to results observed in a study conducted by Madan et al.[15] with 60% of invasive breast carcinomas demonstrated with membranous paxillin expression.

MDSCC and PDSCC demonstrated the paxillin expression throughout the tumor cells; however, the WDSCC demonstrated paxillin expression only in the peripheral cell and the expression was not evident in central keratinizing areas. This might be due to the fact that peripheral cells represent the proliferative component, and the positivity of the paxillin may be recognized to the activation of GTPases of both Ras and Rho families, including Rap1, Rac1, Cdc42 and Rho GTPases involved in various functions including cell proliferation, cell survival and migration.[12]

When the paxillin expression was evaluated for the percentage of cell exhibiting positivity, >50% of positivity for paxillin immunostaining was demonstrated in majority of the cases in all the study groups. It was observed that increased percentage of positivity was demonstrated with increasing grade. This was correlated to the study conducted by Shi et al.[5] in which most of the expression was recognized as cytoplasmic staining and associated with clinical stage and distant metastasis, but not with histologic type.[5]

A study conducted by Chen et al.[9] showed the deregulation of paxillin gene involving in the metastasis and progression of different malignancies with colorectal cancer. Among 247 cases evaluated, positive paxillin staining was observed in 80.1% of the cases while no or weak staining was observed in the neighboring noncancerous area. However, in the present study, 90% of positive cells were observed in MDSCC. The study also showed upregulation of paxillin in gastric carcinoma tissues and cell lines as compared to the normal gastric epithelial cell lines. The present study also showed the similar progressive increase in the paxillin expression in the different grades of OSCC.

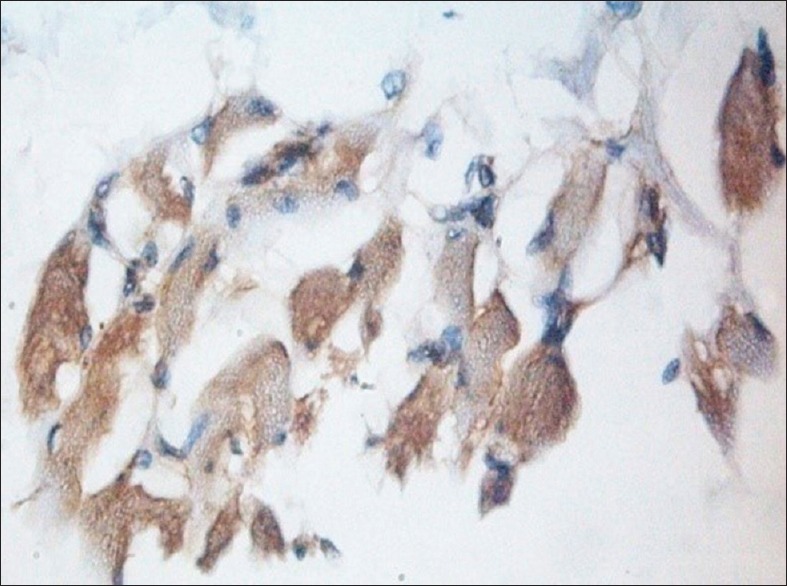

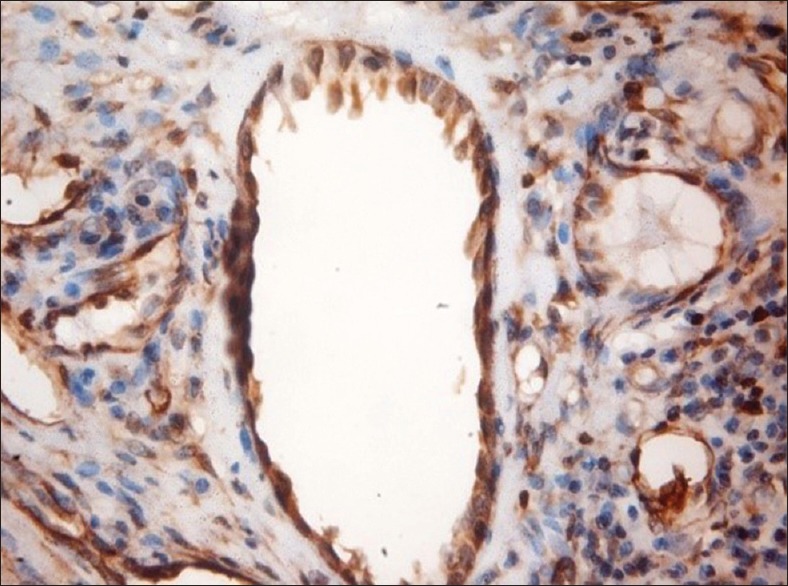

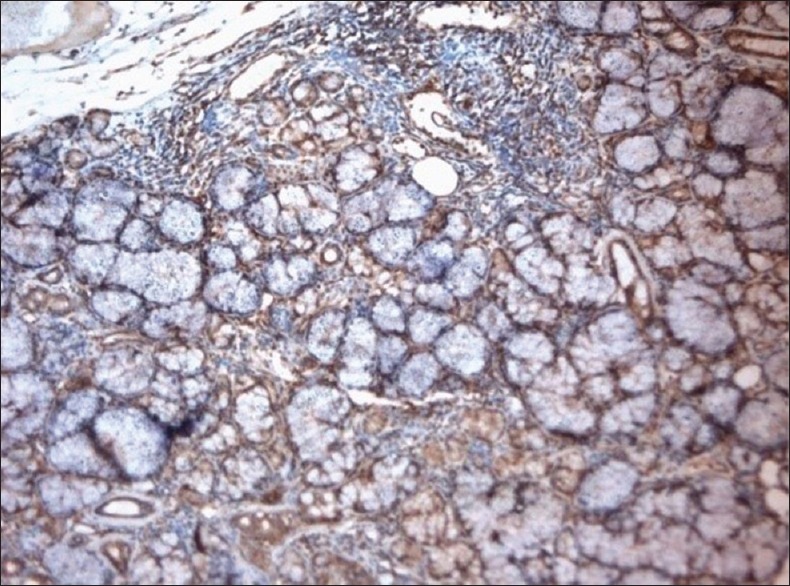

Other findings of the study showed that the paxillin expression was evident in the nontumorous tissues including the muscle, nerve, endothelial cells and the inflammatory infiltrate, which were associated with the tumors [Figures 2–5]. A study conducted by Yuminamochi et al.[16] showed expression of paxillin in skeletal and cardiac muscles, which also showed the widespread nature of paxillin in muscle and nonmuscle tissues. This was similar to the present study in which the paxillin expression was seen in striated muscles. A study conducted by Leventhal et al.[17] stated the role of paxillin in regulation of neurite outgrowth by regulating the cell morphology since it is a tyrosine-phosphorylated protein. This was in accordance to the present study, which showed positivity in the nerve tissue. Further, a study conducted by Parsons et al.[18] depicted the role of paxillin in adaptable neutrophil transmigration. The present study also showed the positivity of paxillin expression in inflammatory infiltrate.

Figure 2.

Muscle fibers showing intense paxillin immunoexpression, ×40

Figure 5.

Paxillin expression in blood vessels, ×40

Figure 3.

Paxillin-positive nerve, ×40

Figure 4.

Paxillin-positive salivary gland acini and ductal cell, ×10

CONCLUSION

The present study provides evidence that paxillin may be involved in the development and progression of OSCC by altering the adhesive properties of the tumor cells interacting with the extracellular matrix, which in turn affects their invasive behavior and histologic differentiation. Thus, paxillin could be considered a useful biomarker for patient management and prognosis. However, the current investigation only concerned a restricted number of patients and relatively few clinical events, limiting our ability to draw more precise conclusions. Further advanced studies should make use of a larger patient group to assess paxillin activity and to study the exact mechanism of the pathogenesis of OSCC and its implication in management strategies.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Wu DW, Chuang CY, Lin WL, Sung WW, Cheng YW, Lee H, et al. Paxillin promotes tumor progression and predicts survival and relapse in oral cavity squamous cell carcinoma by microRNA-218 targeting. Carcinogenesis. 2014;35:1823–9. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgu102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Turner CE. Paxillin interactions. J Cell Sci. 2000;113(Pt 23):4139–40. doi: 10.1242/jcs.113.23.4139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wozniak MA, Modzelewska K, Kwong L, Keely PJ. Focal adhesion regulation of cell behavior. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2004;1692:103–19. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2004.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gao W, Zhang C, Feng Y, Chen G, Wen S, Huangfu H, et al. Fascin-1, ezrin and paxillin contribute to the malignant progression and are predictors of clinical prognosis in laryngeal squamous cell carcinoma. PLoS One. 2012;7:e50710. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0050710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shi J, Wang S, Zhao E, Shi L, Xu X, Fang M, et al. Paxillin expression levels are correlated with clinical stage and metastasis in salivary adenoid cystic carcinoma. J Oral Pathol Med. 2010;39:548–51. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.2009.00859.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tremblay L, Hauck W, Aprikian AG, Begin LR, Chapdelaine A, Chevalier S, et al. Focal adhesion kinase (pp125FAK) expression, activation and association with paxillin and p50CSK in human metastatic prostate carcinoma. Int J Cancer. 1996;68:164–71. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0215(19961009)68:2<169::aid-ijc4>3.0.co;2-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jagadeeswaran R, Surawska H, Krishnaswamy S, Janamanchi V, Mackinnon AC, Seiwert TY, et al. Paxillin is a target for somatic mutations in lung cancer: Implications for cell growth and invasion. Cancer Res. 2008;68:132–42. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vadlamudi R, Adam L, Tseng B, Costa L, Kumar R. Transcriptional up-regulation of paxillin expression by heregulin in human breast cancer cells. Cancer Res. 1999;59:2843–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen DL, Wang DS, Wu WJ, Zeng ZL, Luo HY, Qiu MZ, et al. Overexpression of paxillin induced by miR-137 suppression promotes tumor progression and metastasis in colorectal cancer. Carcinogenesis. 2013;34:803–11. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgs400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rosanò L, Spinella F, Di Castro V, Nicotra MR, Albini A, Natali PG, et al. Endothelin receptor blockade inhibits molecular effectors of Kaposi's sarcoma cell invasion and tumor growth in vivo . Am J Pathol. 2003;163:753–62. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63702-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Swaminathan U, Joshua E, Rao UK, Ranganathan K. Expression of p53 and Cyclin D1 in oral squamous cell carcinoma and normal mucosa: An immunohistochemical study. J Oral Maxillofac Pathol. 2012;16:172–7. doi: 10.4103/0973-029X.98451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen DL, Wang ZQ, Ren C, Zeng ZL, Wang DS, Luo HY, et al. Abnormal expression of paxillin correlates with tumor progression and poor survival in patients with gastric cancer. J Transl Med. 2013;11:277. doi: 10.1186/1479-5876-11-277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Panousis D, Xepapadakis G, Lagoudianakis E, Karavitis G, Salemis N, Koronakis N, et al. Prognostic value of EZH2, paxillin expression and DNA ploidy of breast adenocarcinoma: Correlation to pathologic predictors. J BUON. 2013;18:879–85. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mackinnon AC, Tretiakova M, Henderson L, Mehta RG, Yan BC, Joseph L, et al. Paxillin expression and amplification in early lung lesions of high-risk patients, lung adenocarcinoma and metastatic disease. J Clin Pathol. 2011;64:16–24. doi: 10.1136/jcp.2010.075853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Madan R, Smolkin MB, Cocker R, Fayyad R, Oktay MH. Focal adhesion proteins as markers of malignant transformation and prognostic indicators in breast carcinoma. Hum Pathol. 2006;37:9–15. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2005.09.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yuminamochi T, Yatomi Y, Osada M, Ohmori T, Ishii Y, Nakazawa K, et al. Expression of the LIM proteins paxillin and Hic-5 in human tissues. J Histochem Cytochem. 2003;51:513–21. doi: 10.1177/002215540305100413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Leventhal PS, Shelden EA, Kim B, Feldman EL. Tyrosine phosphorylation of paxillin and focal adhesion kinase during insulin-like growth factor-I-stimulated lamellipodial advance. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:5214–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.8.5214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Parsons SA, Sharma R, Roccamatisi DL, Zhang H, Petri B, Kubes P, et al. Endothelial paxillin and focal adhesion kinase (FAK) play a critical role in neutrophil transmigration. Eur J Immunol. 2012;42:436–46. doi: 10.1002/eji.201041303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]