Abstract

Background

Hepatitis B virus (HBV) is predominantly transmitted through mother-to-child transmission (MTCT). To date, it remains unclear whether the method of parturition affects MTCT of HBV. In order to clarify whether cesarean section, when compared with vaginal delivery, could reduce the risk of MTCT of HBV in China, we conducted this meta-analysis.

Methods

A systematic literature search was performed of the PubMed (Medline), Embase, ISI Web of Science, China Biological Medicine Database, China National Knowledge Infrastructure, and VIP Database for Chinese Technical Periodicals databases for articles written in English or Chinese through July 2015.The reference lists of relevant articles were also scrutinized for additional papers. Randomized controlled trials, cohort studies, or case-control studies investigating the effect of delivery mode on MTCT of HBV were included.

Results

This analysis involved 28 articles containing 30 datasets. The data encompassed 9906 participants. The MTCT rate of HBV was 6.76% (670 of 9906) overall, with individual rates of 4.37% (223 of 5105) for mothers who underwent cesarean section and 9.31% (447 of 4801) for those who underwent vaginal delivery. The summary relative risk (RR) was 0.51 (95%CI: 0.44–0.60, P < 0.001), indicating a statistically significant decrease in HBV vertical transmission via cesarean section compared with vaginal delivery. The heterogeneity among studies was moderate with an I 2of29.3%.Publication bias was not detected by the Egger’s and Begg’s tests, and the funnel plot was symmetric. In the subgroup analyses, maternal hepatitis B e antigen status and follow-up time did not affect the significance of the results, but hepatitis B immune globulin (HBIG) administration to mother and infant did.

Conclusions

Cesarean section could reduce the risk of MTCT of HBV in comparison to vaginal delivery in China. However, owing to several limitations of our meta-analysis, future well-designed randomized controlled trials with adequate statistical power, might be a more appropriate next step.

Keywords: Cesarean section, Hepatitis B virus, Mother-to-child transmission, Meta-analysis

Background

Hepatitis B is a potentially life-threatening liver infection caused by hepatitis B virus (HBV). It is a major global health problem. It can cause chronic infection and puts people at high risk of death from cirrhosis and liver cancer. According to the World Health Organization, an estimated 240 million people have chronic hepatitis B infection [1]. More than 780,000 people die every year due to complications of hepatitis B infection, including cirrhosis and liver cancer [2]. Hepatitis B prevalence is highest in sub-Saharan Africa and East Asia, where 5–10% of the adult population is chronically infected. The infected population of China accounts for one-third of the infected population worldwide [3].

HBV is predominantly transmitted through mother-to-child transmission (MTCT). In China, 30–50% of HBV carriers are infected through vertical transmission [3, 4]. Since the introduction of universal screening of pregnant women, combined with passive and active immunoprophylaxis, the MTCT rate of HBV has declined significantly. Passive immunoprophylaxis consists of the administration of hepatitis B immune globulin (HBIG) at birth, and active immunoprophylaxis is performed by the administration of the hepatitis B vaccine according to the standard 3-dose schedule. Although HBIG and vaccines given at birth are able to reduce transmission in most cases, in 10% to 20% of cases of infected mothers, transmission still occurs, especially from mothers with high viral loads and who are positive for hepatitis B e antigen (HBeAg) [5, 6].

Previous studies demonstrated that cesarean section might reduce the risk of MTCT for some viruses, such as human immunodeficiency virus and herpes simplex virus [7–9]. Numerous studies in China have sought to examine the relationship between delivery mode and rate of MTCT of HBV [10–16]. However, the effect of different delivery modes on MTCT of HBV remains unclear. To elucidate the question of whether cesarean section, as compared to vaginal delivery, may reduce the risk of MTCT of HBV, we conducted this meta-analysis.

Methods

Search strategy

A systematic literature search was performed of the PubMed (Medline), Embase, ISI Web of Science, China Biological Medicine Database, China National Knowledge Infrastructure, and VIP Database for ChineseTechnical Periodicals databases for articles written in English or Chinese through July 2015.The following search terms were used:“hepatitis B virus” or “HBV,”, “mother-to-child transmission” or “vertical transmission”, “cesarean section” or “vaginal delivery” or “natural delivery” or “delivery mode”. We also scrutinized the reference lists of relevant articles included in our analysis and previous systematic reviews and meta-analyses for additional papers. We did not contact the authors of the primary studies for additional information.

Study selection

Studies were included in this meta-analysis if they satisfied the following criteria:

1) Studies were randomized controlled trials, cohort studies, or case-control studies; 2) the participants were pregnant mothers with chronic HBV infection, defined as maternal blood positive for HbsAg; 3) the intervention of interest was cesarean section and the comparison was vaginal delivery; 4) the outcome was vertical transmission of HBV, defined as infant HBsAg and/or HBV DNA positivity. Reviews, editorials, case reports/series, overlapping studies, and duplicates were excluded. We also excluded studies with patients co-infected with hepatitis C virus, hepatitis D virus, and/or human immunodeficiency virus. If the same population was studied in more than one study, we included the study with the largest sample size.

Quality assessment

Our study used a 9-score system based on the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) to assess the original study quality. The maximum score of 9 points could be assigned to a study that had the highest methodological quality, with 4, 2, 3 scores respectively being assigned to selection of study groups, comparability of study groups, assessment of outcomes, and adequacy of follow-up. Studies with scores of 0–3, 4–6, or 7–9 were regarded as low, moderate, and high quality, respectively (Table 1).

Table 1.

Quality assessment of included studies

| Studies | Selection | Comparability | Outcome | Total scores | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Representativeness of the exposed group | Selection of the unexposed group | Ascertainment of exposure | Outcome of interest not present at start of study | Control for important factor or additional factor | Outcome assessment | Follow-up long enough for outcome to occur | Adequacy of follow-up of cohorts | ||

| Wang Qingtu, 2001 [45] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | – | – | 7 |

| Wang Jianshe, 2002 [16] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 9 |

| Wang Lan, 2004 [44] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | – | 1 | 1 | 1 | 7 |

| Wang Yuan, 2005 [43] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 9 |

| Gu Jie, 2006 [42] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 9 |

| Qian Yanhua, 2006 [41] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 8 |

| Fan Yi, 2007 [40] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 9 |

| Chen Jing1, 2007 [38] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 8 |

| Chen Jing2, 2007 [38] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 8 |

| Li Jijun1, 2007 [39] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 8 |

| Li Jijun2, 2007 [39] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 8 |

| Chen Hong, 2008 [37] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 8 |

| Liu Xia, 2008 [36] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | – | 1 | 1 | 1 | 7 |

| Liu Honge, 2009 [35] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 8 |

| Zhang Qingying, 2009 [34] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 9 |

| Zhu Yunxia, 2010 [32] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 9 |

| Yang Peifang, 2010 [33] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 9 |

| Yang Xiaomei, 2011 [30] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 9 |

| Zhang Weili, 2011 [31] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 8 |

| Huang Liu, 2012 [29] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 9 |

| Guo Zhen, 2013 [15] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 9 |

| Wang Ling, 2013 [28] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 9 |

| Hu Yali, 2013 [14] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 9 |

| Yin Yuzhu, 2013 [12] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 9 |

| Pan Calvin Q., 2013 [13] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 8 |

| Zhang Lei, 2014 [11] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 9 |

| Wang Lina, 2014 [26] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 9 |

| Li Weiru, 2014 [25] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 9 | |

| Huang Dan, 2014 [27] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 9 |

| Liu Cuiping, 2015 [10] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 9 |

Data extraction

Two authors (MY and QQ) independently conducted the data extraction process using a standard extraction form. When discrepancies arose, a third author (QF) was consulted. The following information was extracted from each study: first author’s name, publication year, study area, study design, number of infants born by cesarean section or by vaginal delivery, number of infants positive for HBV born by cesarean section or by vaginal delivery, percentage of mothers positive for HBeAg (HBeAg+), intervention administered (HBIG and/or antiviral treatment), percent age of infants who received HBIG, percent age of infants who received the HBV vaccine as scheduled, and the follow-up time of the study.

Statistical analysis

In this meta-analysis, the relative risk (RR) and 95% confidence interval (CI) of HBV MTCT in cesarean section compared to vaginal delivery were considered as the effect size for all studies. Any results stratified by maternal HBeAg status were treated as two separate reports.

The heterogeneity between studies was assessed using the Cochran Q test and I 2 statistic [17]. For the I 2 metric, I 2 values of 25, 50, and 75% represent low, moderate, and high degrees of heterogeneity, respectively [18]. The fixed effect model (Mantel-Haenszel method) was applied to pool the effect when heterogeneity level was low; otherwise, the random effect model described by DerSimonian and Laird was utilized [19].

Subgroup analyses were conducted according to maternal HBeAg status, maternal HBIG administration and/or antiviral treatment, infant immunoprophylaxis status with HBIG, and follow-up time. Sensitivity analysis was performed by omitting one study at a time to examine the influence of each individual study on the overall relative risk. Publication bias was evaluated by Egger’s regression test [20], Begg’s adjusted rank correlation test [21], and visual inspection of the funnel plot. All tests were two-sided and P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were conducted with Stata 11.0 (StataCorp, College Station, TX).

Results

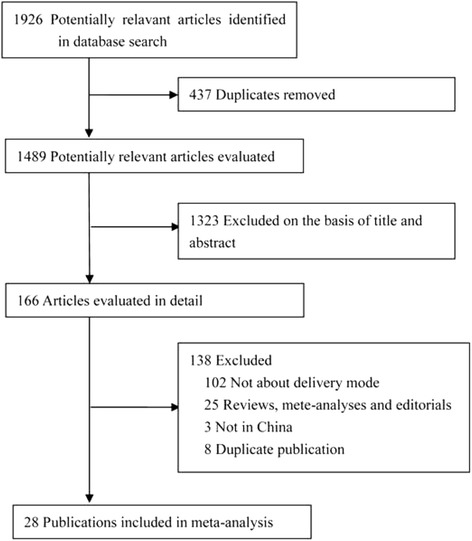

The flow diagram for literature research and study selection is shown in Fig. 1. After screening the title and/or abstract of 1489 potentially relevant articles, 166 articles were evaluated in detail. Of these, 3 articles [22–24] were excluded for not having been conducted in China. Finally, 28 publications [10–16, 25–45] were eligible for inclusion in the meta-analysis.

Fig. 1.

The flow diagram for literature research and study selection

Table 2 displays the main characteristics of the identified studies on the effect of delivery mode on MTCT of HBV. All included articles were published in the period between 2001 and 2015. Among the articles, 2 were case-control studies. All of the others were retrospective cohort studies. Seven were published in English, and the others were published in Chinese. Two articles reported the results grouped by maternal HBeAg status. Six studies were conducted exclusively in HBeAg + mothers, two were conducted solely in HBeAg-mothers, eight did not specify this information, and the remaining studies had mixed HBeAg + and HBeAg- populations (HBeAg + range from 3.83% to 67.19%). Two studies were conducted among pregnant women who all received HBIG administration, nine were conducted among those without HBIG administration, 15 did not specify, and four had mixed populations (HBIG range from 21.93 to 80%). One study was conducted with 7.81% of the mothers having received antiviral therapy, 14 were conducted among those who had not received antiviral therapy, and the remaining did not report whether antiviral therapy had been administered. Infants were tested for HBV within 24 h of birth before immunoprophylaxis in 6 studies. Among the studies with a follow-up period of more than 1 month, all infants received the hepatitis B vaccine in 24 studies. With regard to HBIG administration in infants in these 24 studies, 17 studies were conducted with 100% administration, 3 did not report this information, and 4 studies had a range from 53.3 to 84.34%.

Table 2.

Characteristics of identified studies in this meta-analysis

| Study | Newborns | HBV+ newborns | Mothers | Infants | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Author | Year | Area | design | Caesarean | Vaginal | Caesarean | Vaginal | HBeAg + (%) | Intervention | HBIG | Vaccine | Follow-up |

| Wang Qingtu | 2001 | Shandong | RC | 38 | 84 | 4 | 28 | 100 | NR | NR | NR | 1 h |

| Wang Jianshe | 2002 | Shanghai | RC | 117 | 184 | 13 | 17 | 36.54 | NR | 100% | 1, 2 and 7 months | 12 months |

| Wang Lan | 2004 | Shandong | RC | 61 | 183 | 11 | 61 | 100 | NR | 75.82% | 0, 1 and 6 months | 1 month |

| Wang Yuan | 2005 | Jiangsu | RC | 58 | 42 | 1 | 0 | 22 | 100% HBIG | 100% | 0, 1 and 6 months | 2 month |

| Gu Jie | 2006 | Ningxia | RC | 64 | 85 | 2 | 5 | 34.9 | No | 100% | 0, 1 and 6 months | 12 months |

| Qian Yanhua | 2006 | Jiangsu | RC | 26 | 24 | 0 | 2 | NR | 80% HBIG | 80% | 0, 1 and 6 months | 12 months |

| Fan Yi | 2007 | Guangdong | RC | 92 | 103 | 2 | 9 | 4.1 | NR | 100% | 0, 1 and 6 months | 6 months |

| Chen Jing1 | 2007 | Tianjin | RC | 176 | 53 | 27 | 13 | 100 | NR | NR | NR | 1 h |

| Chen Jing2 | 2007 | Tianjin | RC | 112 | 68 | 3 | 10 | 0 | NR | NR | NR | 1 h |

| Li Jijun1 | 2007 | Gansu, Jiangsu | RC | 12 | 49 | 4 | 19 | 100 | NR | NR | 0, 1 and 6 months | 3–9 years |

| Li Jijun2 | 2007 | Gansu, Jiangsu | RC | 74 | 184 | 5 | 28 | 0 | NR | NR | 0, 1 and 6 months | 3–9 years |

| Chen Hong | 2008 | Beijing | RC | 112 | 180 | 4 | 5 | 4.45 | No | NR | 0, 1 and 6 months | 6 months |

| Liu Xia | 2008 | Tianjin | RC | 153 | 54 | 14 | 15 | NR | NR | NR | NR | 2 h |

| Liu Honge | 2009 | Guangdong | RC | 86 | 123 | 2 | 9 | 3.83 | NR | 100% | 0, 1 and 6 months | 1 month |

| Zhang Qingying | 2009 | Shanghai | RC | 166 | 52 | 1 | 7 | NR | No | 100% | 0, 1 and 6 months | 6 months |

| Zhu Yunxia | 2010 | Beijing | RC | 114 | 102 | 5 | 6 | 100 | No | 100% | 0, 1 and 6 months | 7 months |

| Yang Peifang | 2010 | Shanghai | RC | 32 | 36 | 0 | 1 | 19.1 | No | 100% | 0, 1 and 6 months | 12 months |

| Yang Xiaomei | 2011 | Guangdong | RC | 33 | 49 | 4 | 7 | NR | NR | 100% | 0, 1 and 6 months | 6 months |

| Zhang Weili | 2011 | Shanghai | RC | 508 | 127 | 17 | 5 | NR | NR | 100% | 0, 1 and 6 months | 3 months |

| Huang Liu | 2012 | Guangdong | RC | 122 | 168 | 9 | 17 | NR | NR | NR | NR | 24 h |

| Guo Zhen | 2013 | Shanxi | CC | 584 | 549 | 29 | 72 | 36.19 | NR | NR | NR | 24 h |

| Wang Ling | 2013 | Sichuan | RC | 112 | 148 | 7 | 16 | NR | 100% HBIG | 100% | 0, 1 and 6 months | 6 months |

| Hu Yali | 2013 | Jiangsu | RC | 285 | 261 | 7 | 6 | 24.73 | NR | 53.30% | 0, 1 and 6 months | 5–7 years |

| Yin Yuzhu | 2013 | Guangdong | RC | 692 | 668 | 12 | 9 | 34.76 | 39.70% HBIG | 100% | 0, 1 and 6 months | 12 months |

| Pan Calvin Q. | 2013 | Beijing | RC | 496 | 673 | 7 | 23 | 54.5 | No | 100% | 0, 1 and 6 months | 7–12 months |

| Zhang Lei | 2014 | Multicenter | RC | 221 | 194 | 17 | 22 | 100 | 21.93% HBIG | 84.34% | 0, 1 and 6 months | 8-12 months |

| Wang Lina | 2014 | Guangdong | RC | 149 | 122 | 6 | 9 | 34.32 | No | 100% | 0, 1 and 6 months | 7–12 months |

| Li Weiru | 2014 | Guangdong | RC | 120 | 120 | 2 | 12 | NR | No | 100% | 0, 1 and 6 months | 6 months |

| Huang Dan | 2014 | Hubei | RC | 86 | 64 | 4 | 8 | 18.67 | No | 100% | 0, 1 and 6 months | 6 months |

| Liu Cuiping | 2015 | Sichuan | CC | 204 | 52 | 4 | 6 | 67.19 | 7.81% antiviral; 43.36% HBIG | 100% | 0, 1 and 6 months | 6–12 months and/or 1–3 years |

Meta-analysis

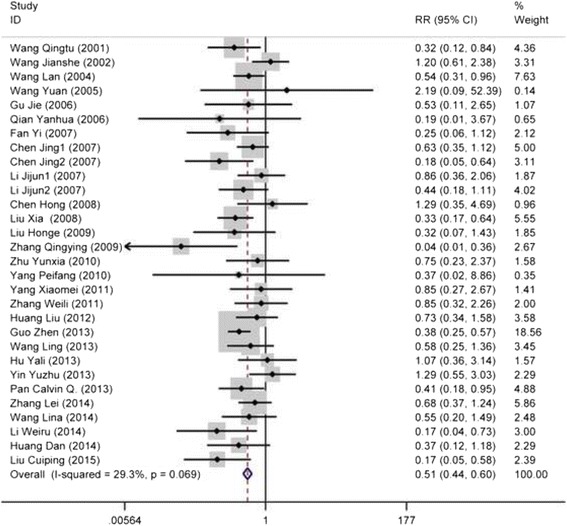

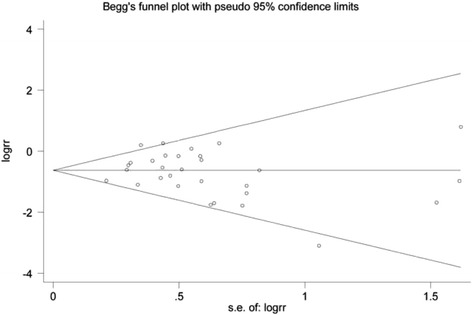

This analysis involved 28 articles with 30 datasets comprising 9906 participants. The MTCT rate of HBV was 6.76% (670 of 9906) overall, with individual rates of 4.37% (223 of 5105) for mothers who underwent cesarean section and 9.31% (447 of 4801) for those who underwent vaginal delivery. The study-specific RRs and the pooled estimate are shown in Fig. 2. The summary RR was 0.51 (95%CI: 0.44–0.60, P < 0.001), indicating a statistically significant decrease in HBV vertical transmission with cesarean section, as compared to vaginal delivery. The heterogeneity among studies was moderate with I 2of29.3% (P heterogeneity = 0.069). In the sensitivity analysis, the pooled RRs were similar before and after removal of each study, indicating the robust stability of the current result. Publication bias was not detected by Egger’s (P = 0.452) and Begg’s (P = 0.254) tests, and the funnel plot was symmetric (Fig. 3).

Fig. 2.

The forest plot of the efficacy of caesarean section versus vaginal delivery for preventing hepatitis B virus vertical transmission

Fig. 3.

Funnel plot of publication bias

Subgroup analyses were conducted to examine the stability of the primary result (Table 3). Significant results did not differ substantially by maternal HBeAg status and follow-up time. As for the stratified analyses by maternal HBIG administration, the risk of MTCT of HBV was significantly decreased in the cases of cesarean section when compared to vaginal delivery among pregnant women without HBIG administration and those where HBIG administration had not been specified, but not among those with HBIG administration (100% or mixed). A significant effect of cesarean section on the MTCT of HBV was found in those studies where either 100% or a smaller percentage of infants had been administered HBIG, as well as in studies where administration of HBIG to infants had not been reported. With regard to infant vaccination, the significant effect of cesarean section did not differ among infants who received vaccination and those whose vaccination status was unknown.

Table 3.

Subgroup analyses on the effect of delivery mode on the risk of hepatitis B virus vertical transmission

| Characteristic | No. of reports | RR (95% CI) | P for test | I 2(%) | P for heterogeneity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All studies | 30 | 0.51 (0.44–0.60) | <0.001 | 29.3 | 0.069 |

| Maternal HbeAg status | |||||

| HBeAg+ | 6 | 0.59 (0.44–0.78) | <0.001 | 0.0 | 0.731 |

| HBeAg- | 2 | 0.33 (0.16–0.68) | 0.003 | 21.1 | 0.260 |

| Mixed | 14 | 0.53 (0.42–0.68) | <0.001 | 40.3 | 0.059 |

| Not reported | 8 | 0.45 (0.32–0.63) | <0.001 | 43.2 | 0.090 |

| Maternal HBIG administration | |||||

| Yes (100%) | 2 | 0.63 (0.28–1.44) | 0.276 | 0.0 | 0.427 |

| No | 9 | 0.44 (0.27–0.72) | 0.001 | 22.1 | 0.247 |

| Mixed | 4 | 0.54 (0.23–1.30) | 0.169 | 61.2 | 0.052 |

| Not reported | 15 | 0.54 (0.42–0.70) | <0.001 | 32.9 | 0.105 |

| Infant HBIG administration | |||||

| Yes (100%) | 17 | 0.55 (0.42–0.71) | <0.001 | 36.9 | 0.064 |

| Mixed | 4 | 0.63 (0.43–0.92) | 0.017 | 0.0 | 0.594 |

| Not reported | 9 | 0.45 (0.35–0.57) | <0.001 | 29.7 | 0.182 |

| Infant vaccine | |||||

| 0–1-6 months | 23 | 0.55 (0.44–0.67) | <0.001 | 14.1 | 0.268 |

| 1–2-7 months | 1 | – | – | – | – |

| Not reported | 6 | 0.41 (0.32–0.54) | <0.001 | 23.7 | 0.256 |

| Follow-up time | |||||

| ≥ 1 month | 24 | 0.58 (0.48–0.71) | <0.001 | 22.7 | 0.157 |

| ≤ 24 h | 6 | 0.41 (0.32–0.54) | <0.001 | 23.7 | 0.256 |

| Region | |||||

| EDA | 22 | 0.55 (0.45–0.67) | <0.001 | 34.8 | 0.056 |

| CLDA | 2 | 0.38 (0.26–0.56) | <0.001 | 0.0 | 0.978 |

| WUDA | 3 | 0.43 (0.23–0.80) | 0.008 | 26.6 | 0.256 |

| Mixed | 3 | 0.63 (0.40–0.97) | 0.037 | 0.0 | 0.573 |

Abbreviations: HBeAg hepatitis B e antigen, HBIG hepatitis B immune globulin, RR relative risk, CI confidence interval, EDA eastern developed areas, CLDA central less developed areas, WUDA western or undeveloped areas

Discussion

In this meta-analysis, we found that cesarean section could significantly reduce the risk of MTCT of HBV in China. The significant effect was not affected by maternal HBeAg status and follow-up time, but was influenced by both maternal and infant HBIG administration. Our results are consistent with the findings of two previous meta-analyses [46, 47]; however, one only included 4 studies and another included 10 studies worldwide. In the meta-analysis reported by Chang et al. [46], most of the included studies were performed in China, but some Chinese articles were excluded owing to the lack of available translations. We were able to take full advantage of Chinese databases and include 28 studies performed in China in this meta-analysis, making it the largest and most robust meta-analysis to date.

The mechanism of MTCT of HBV remains unclear. Most MTCTs likely occur perinatally by microperfusion of maternal blood to the fetal circulation during the uterine contractions and tearing of the placenta at birth. Other possible modes of infection include swallowing amniotic fluid, vaginal secretions, or exposure to maternal blood during vaginal delivery [13]. Elective cesarean section results in the least amount of placental contraction and has been speculated to involve the least maternal-fetal transfusion [15]. It also limits direct contact of the fetus with infected secretions or blood in the maternal genital tract.

Several limitations of our meta-analysis should be acknowledged. Despite demonstrating the efficacy of cesarean section for preventing MTCT of HBV, the conclusion of this study must be considered with great caution. Firstly, the included studies were retrospective cohort and case-control studies, not randomized controlled trials. Some bias and confounding factors could not be well controlled in the retrospective studies. Secondly, the data on maternal HBV DNA level in the included studies were lacking, making it difficult to reach conclusions. The maternal HBV DNA level was considered as the most important independent risk factor for vertical transmission by many studies [5, 48, 49]. Thirdly, although we found the significant effect did not differ by maternal HBeAg status, in most of the studies we included, the authors did not report maternal HBeAg status, or the participants had mixed HBeAg statuses. HBeAg positivity had a close relationship with HBV DNA level. Finally, HBIG administration and antiviral therapy in pregnant women were not reported in most studies. The results may have been affected by the lack of these data. In addition, owing to missing clinical details on hepatitis B, varying study quality, and study heterogeneity, it would be difficult to justify a randomized trial of cesarean section, which is currently an unproven and invasive intervention. A detailed, well-designed observational study, where all infants receive HBIG and vaccination and all mothers experience perinatal hepatitis B care, might be a more appropriate next step.

Conclusions

Our meta-analysis found that cesarean section could reduce the risk of MTCT of HBV in comparison to vaginal delivery in China. Whether elective cesarean section can be recommended for clinical practice as a preventive measure against MTCT of HBV should be considered with caution. Future well-designed randomized control trials with adequate statistical power will be needed to confirm our findings.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge Li Liu for her assistance with identifying and screening the abstracts of studies obtained from the searched databases.

Funding

This work was supported by the Health Public Welfare Project of Futian District (FTWS2015048) and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC81172752). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- CLDA

Central less developed areas

- EDA

Eastern developed areas

- HBeAg

Hepatitis B e antigen

- HBIG

Hepatitis B immune globulin

- HBV

Hepatitis B virus

- MTCT

Mother-to-child transmission

- NOS

Newcastle-Ottawa Scale

- WUDA

Western or undeveloped areas

Authors’ contributions

MY, QQ, and SFN were responsible for the design and concept of the manuscript. MY, QQ, QF, and LXJ were responsible for the literature search and retrieving data, and MY and QQ were responsible for analyzing the data. All authors were responsible for writing the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interest.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Mei Yang, Email: 291368212@qq.com.

Qin Qin, Email: qq693267064@163.com.

Qiong Fang, Email: 610464588@qq.com.

Lixin Jiang, Email: 63889065@qq.com.

Shaofa Nie, Phone: 86-27-83693763, Email: sf_nie@mails.tjmu.edu.cn.

References

- 1.World Health Organization. http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs204/en/. Updated July 2015.

- 2.Lozano R, Naghavi M, Foreman K, Lim S, Shibuya K, Aboyans V, Abraham J, Adair T, Aggarwal R, Ahn SY, et al. Global and regional mortality from 235 causes of death for 20 age groups in 1990 and 2010: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2010. Lancet. 2012;380(9859):2095–2128. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61728-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cui Y, Jia J. Update on epidemiology of hepatitis B and C in China. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;28(Suppl 1):7–10. doi: 10.1111/jgh.12220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lv N, Chu XD, Sun YH, Zhao SY, Li PL, Chen X. Analysis on the outcomes of hepatitis B virus perinatal vertical transmission: nested case-control study. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;26(11):1286–1291. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0000000000000189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pan CQ, Han GR, Jiang HX, Zhao W, Cao MK, Wang CM, Yue X, Wang GJ. Telbivudine prevents vertical transmission from HBeAg-positive women with chronic hepatitis B. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;10(5):520–526. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2012.01.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tran TT. Hepatitis B and pregnancy. Curr Hepat Rep. 2009;8(3):91–95. doi: 10.1007/s11901-009-0013-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Legardy-Williams JK, Jamieson DJ, Read JS. Prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV-1: the role of cesarean delivery. Clin Perinatol. 2010;37(4):777–785. doi: 10.1016/j.clp.2010.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sauerbrei A, Wutzler P. Herpes simplex and varicella-zoster virus infections during pregnancy: current concepts of prevention, diagnosis and therapy. Part 1: herpes simplex virus infections. Med Microbiol Immunol. 2007;196(2):89–94. doi: 10.1007/s00430-006-0031-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Read JS, Newell MK. Efficacy and safety of cesarean delivery for prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV-1. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005;4:CD005479. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liu CP, Zeng YL, Zhou M, Chen LL, Hu R, Wang L, Tang H. Factors associated with mother-to-child transmission of hepatitis B virus despite immunoprophylaxis. Inter Med (Tokyo, Japan) 2015;54(7):711–716. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.54.3514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhang L, Gui X, Wang B, Ji H, Yisilafu R, Li F, Zhou Y, Zhang L, Zhang H, Liu X. A study of immunoprophylaxis failure and risk factors of hepatitis B virus mother-to-infant transmission. Eur J Pediatr. 2014;173(9):1161–1168. doi: 10.1007/s00431-014-2305-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yin Y, Zhou J, Zhang P, Hou H. Identification of risk factors related to the failure of immunization to interrupt hepatitis B virus perinatal transmission. Chin J Hepatol. 2013;21(2):105–110. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.issn.1007-3418.2013.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pan CQ, Zou HB, Chen Y, Zhang X, Zhang H, Li J, Duan Z. Cesarean section reduces perinatal transmission of hepatitis B virus infection from hepatitis B surface antigen-positive women to their infants. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;11(10):1349–1355. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2013.04.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hu Y, Chen J, Wen J, Xu C, Zhang S, Xu B, Zhou YH. Effect of elective cesarean section on the risk of mother-to-child transmission of hepatitis B virus. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2013;13:119. doi: 10.1186/1471-2393-13-119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Guo Z, Shi XH, Feng YL, Wang B, Feng LP, Wang SP, Zhang YW. Risk factors of HBV intrauterine transmission among HBsAg-positive pregnant women. J Viral Hepat. 2013;20(5):317–321. doi: 10.1111/jvh.12032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang J, Zhu Q, Zhang X. Effect of delivery mode on maternal-infant transmission of hepatitis B virus by immunoprophylaxis. Chin Med J. 2002;115(10):1510–1512. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ (Clinical research ed) 2003;327(7414):557–560. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Higgins JP. Commentary: heterogeneity in meta-analysis should be expected and appropriately quantified. Int J Epidemiol. 2008;37(5):1158–1160. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyn204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lau J, Ioannidis JP, Schmid CH. Quantitative synthesis in systematic reviews. Ann Intern Med. 1997;127(9):820–826. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-127-9-199711010-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Egger M, Davey Smith G, Schneider M, Minder C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ (Clinical research ed) 1997;315(7109):629–634. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7109.629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Begg CB, Mazumdar M. Operating characteristics of a rank correlation test for publication bias. Biometrics. 1994;50(4):1088–1101. doi: 10.2307/2533446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wen WH, Chang MH, Zhao LL, Ni YH, Hsu HY, Wu JF, Chen PJ, Chen DS, Chen HL. Mother-to-infant transmission of hepatitis B virus infection: significance of maternal viral load and strategies for intervention. J Hepatol. 2013;59(1):24–30. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2013.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dwivedi M, Misra SP, Misra V, Pandey A, Pant S, Singh R, Verma M. Seroprevalence of hepatitis B infection during pregnancy and risk of perinatal transmission. Indian J Gastroenterol. 2011;30(2):66–71. doi: 10.1007/s12664-011-0083-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lee SD, Tsai YT, Wu TC, Lo KJ, Wu JC, Yang ZL, Ng HT. Role of caesarean section in prevention of mother-infant transmission of hepatitis B virus. Lancet. 1988;2(8615):833–834. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(88)92792-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li W, Huang P, Jian Y. The impact of delivery mode on the mother-to-child transmission of hepatitis B virus. China Foreign Med Treat. 2014;4(12):51–52. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang L, Li X, Yin B. Effect of delivery mode on hepatitis B virus mother-to-child transmission. Med Front. 2014;19:253–254. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Huang D. Effect of delivery mode on hepatitis B virus mother-to-child vertical transmission. Med Recapitulate. 2014;20(11):2099–2100. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang L. Research on effect of delivery mode on hepatitis B virus mother-to-child transmission. J Guangxi Med Univ. 2013;30(1):188–190. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Huang L, Fan H, Ji B, Ye M. Research about the efficacy of delivery mode on maternal-infant transmission of hepatitis B virus. New Med. 2012;43(4):247–249. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yang X, Gan T, Liu Z, Zhang N: Effects of delivery mode and HBV DNA loads on the mother-to-child transmission of hepatitis B virus. Hainan Med J. 2011;22(1):20-22.

- 31.Zhang W, Zhao J, Li W. Influencing factors of mother-infant vertical transmission of hepatitis B virus. Chin J Contemp Pediatr. 2011;13(8):644–646. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhu Y, Zou H, Chen Y, Zhang H, Duan Z. Effect of different delivery modes on mother-to-infant transmission of hepatitis B virus. J Shanxi Med Univ. 2010;41(6):495–497. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yang P. Effect of delivery mode on mother-to-child vertical transmission of hepatitis B virus. Hebei Med J. 2010;32(3):318–319. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhang Q, Zhao J, Jiang P. Effect of delivery mode on maternal-infant transmission of hepatitis B virus. Chin J Clin Med. 2009;16(4):570–571. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Liu H, Fan H. Research on the relationship between maternal-infant transmission of hepatitis B viru and delivery mode. Chin J Mod Drug Appl. 2009;3(10):30–31. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Xia L, Jinyu H. Clinical study on the relationship between delivery styles of pregnant women with high capacity of HBV and HBV infection of two hour-old newborns. Mod Prev Med. 2008;35(4):790–791. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chen H, Ren J, Liu X. Influence of different delivery patterns on mother··to·-child vertical transmission of HBV. Chin J Woman Child Heahh Res. 2008;19(3):214–216. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chen J, Zhang P. Effect on HBV mother-infant transmission in infectiousness and labor presentation. Med Innov Res. 2007;4(27):8–9. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Li J, Wang F, Zheng H, Liang X. Influence of the different labor types to the HBV mother-to-infant transmission. Chin J Vaccines Immunization. 2007;13(4):306–308. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fan Y, Xiao X, Li A, Tang X. Influence of delivery mode on maternal-infant transmission of hepatitis B virus. Guangdong Med J. 2007;28(2):252–3. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Qian Y. Influence of labor types on the effect of interdicting mother-infant HBV transmission. Occup Health. 2006;22(17):1332–1334. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gu J, Wang Y, Zhao L. Effect of delivery mode on interdicting maternal-infant transmission of hepatitis B virus. Ningxia Med J. 2006;28(11):858–859. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wang Y, He C, Huang W, Cai X, Yao J. Clinical research on factors associated with mother-to-child transmission of hepatitis B virus after combined immunization. Matern Child Health Care China. 2005;20(13):1655–1657. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wang L, Hu W, Wang Q, Qi h. Relationship between delivery mode and maternal-infant transmission of hepatitis B virus. Cent Plains Med J. 2004;31(9):10–11. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wang Q, Xiu X, Guo Y, Tao H. Effect of different delivery modes on interdicting maternal-infant transmission of hepatitis B virus. Shandong Med J. 2001;41(22):44–45. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chang MS, Gavini S, Andrade PC, McNabb-Baltar J. Caesarean section to prevent transmission of hepatitis B: a meta-analysis. Can J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;28(8):439–444. doi: 10.1155/2014/350179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yang J, Zeng XM, Men YL, Zhao LS. Elective caesarean section versus vaginal delivery for preventing mother to child transmission of hepatitis B virus--a systematic review. Virol J. 2008;5:100. doi: 10.1186/1743-422X-5-100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zou H, Chen Y, Duan Z, Zhang H, Pan C. Virologic factors associated with failure to passive-active immunoprophylaxis in infants born to HBsAg-positive mothers. J Viral Hepat. 2012;19(2):e18–e25. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2893.2011.01492.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Han GR, Cao MK, Zhao W, Jiang HX, Wang CM, Bai SF, Yue X, Wang GJ, Tang X, Fang ZX. A prospective and open-label study for the efficacy and safety of telbivudine in pregnancy for the prevention of perinatal transmission of hepatitis B virus infection. J Hepatol. 2011;55(6):1215–1221. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2011.02.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.