Abstract

Deciphering the roles of chemical and physical features of the extracellular matrix (ECM) is vital for developing biomimetic materials with desired cellular responses in regenerative medicine. Here, we demonstrate that sulfation of biopolymers, mimicking the proteoglycans in native tissues, induces mitogenicity, chondrogenic phenotype, and suppresses catabolic activity of chondrocytes, a cell type that resides in a highly sulfated tissue. We show through tunable modification of alginate that increased sulfation of the microenvironment promotes FGF signaling-mediated proliferation of chondrocytes in a three-dimensional (3D) matrix independent of stiffness, swelling, and porosity. Furthermore, we show for the first time that a biomimetic hydrogel acts as a 3D signaling matrix to mediate a heparan sulfate/heparin-like interaction between FGF and its receptor leading to signaling cascades inducing cell proliferation, cartilage matrix production, and suppression of de-differentiation markers. Collectively, this study reveals important insights on mimicking the ECM to guide self-renewal of cells via manipulation of distinct signaling mechanisms.

Keywords: Biomimetics, biomedical applications, hydrogels, tissue engineering

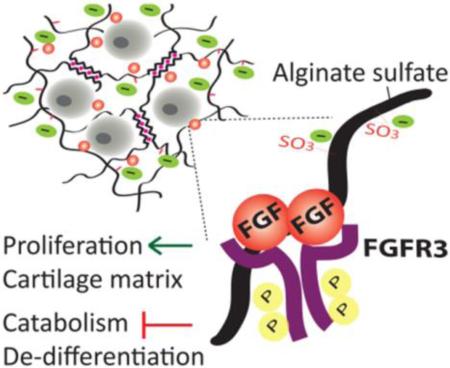

Graphical abstract

A cartilage biomimetic hydrogel based on alginate demonstrates the important function of sulfation in the cellular microenvironment in inducing self-renewal of chondrocytes. Sulfated hydrogels promote extensive three-dimensional growth of chondrocytes decoupled from hydrogel stiffness and porosity. Chondrocytes proliferating in the biomimetic hydrogels are shown to produce vast amount of cartilage matrix and escape de-differentiation via activation of FGF signaling with the hydrogel matrix.

1. Introduction

Regenerative medicine is dependent on the ability of cells to undergo self-renewal without loss of cell potency. Understanding the key features of the native extracellular matrix (ECM) that control processes such as proliferation and differentiation is crucial for developing biomimetic materials that can support self-renewal of cells. The ECM serves as a dynamic microenvironment for cells presenting the specific cues involved in cell-matrix interactions and signaling cascades. The structure of ECM provides information to the resident cells, acting both as a mechanical support and a reservoir of recognition and adhesion ligands, cytokines and growth factors.[1-4] Mimicking the selected characteristics of the native ECM to design biomaterials that control specific cellular functions is an important challenge given the complexity of the matrisome.[5]

Physical properties of the ECM such as stiffness, nanotopography, hydrophilicity, and electric charge as well as chemical composition, and ligand density are vital for manipulating cellular responses.[6-15] One of the major components of the ECM are proteoglycans, which are comprised of a core protein modified by brush-like sulfated glycosaminoglycans (GAGs) such as heparan sulfate (HS)/heparin and chondroitin sulfate.[16-20] These sulfated GAGs are the main contributors of negative charge and hydration in the ECM.[16,21] Moreover, sulfated GAGs confer high affinity to several growth factors in the transforming growth factor (TGF) and fibroblast growth factor (FGF) families and control their relevant sequestration, presentation, activation and signaling in the ECM.[1,15,19,22] Heparin, a highly sulfated GAG, stabilizes and protects basic FGF (FGF2) from acid, heat-mediated or proteolytic degradation.[23] Furthermore, FGF2 has distinct binding domains for FGF receptors (FGFR) and heparan sulfates, and the biological activity of FGF has been shown to depend on the formation of this ternary complex.[24-28] Hence, the sulfation state of the ECM is an important factor for regulation of growth factor signaling in the tissue. Heparin has been commonly used in tissue engineering applications in combination with synthetic and biological materials mainly as a means to stabilize and deliver growth factors.[29,30] Difficulties in working with heparin include fast degradation, impurity, and desulfation. This motivated the development of sulfated mimetics that can bind and stabilize growth factors.[31-33] However, it is still not completely understood how sulfated moieties in a three-dimensional (3D) matrix control growth factor signaling and tissue specific cellular functions.

Cartilage tissue is uniquely enriched in proteoglycans that provide its high water retention and compressive strength along with entrapment and activity of growth factors regulating chondrogenic responses such as TGFβ1/3, FGF18 and FGF2.[17,34-41] The chondrocyte pericellular matrix proteoglycans such as perlecan are actively involved in mediation of FGF signaling in cartilage.[42-46] Several mouse models have shown that sulfation state of the ECM plays an important role for growth plate cartilage morphogenesis controlling FGF signaling to modulate chondrocyte proliferation and differentiation.[47-50] Therefore, a thorough understanding of how chondrocytes respond to this highly sulfated and hydrophilic environment is essential for recapitulating the native chemical and physical cues and guide chondrocytes for cartilage regeneration. Autologous chondrocytes are particularly challenging to use for cartilage repair due to a low cell yield and lack of self-renewal.[51,52] Their two-dimensional (2D) expansion leads to de-differentiation, a phenomenon defined by a loss of expression of cartilage matrix components such as type 2 collagen and proteoglycans and increase in expression of the fibroblastic marker type 1 collagen.[53,54] The regenerative capacity of these de-differentiated chondrocytes whether used directly or in combination with materials is far from ideal. Hence, development of biomimetic materials that stimulate 3D proliferation of freshly isolated chondrocytes and maintenance of their native phenotype is an important challenge to overcome before cell-based therapies can be used reliably.

Here, we investigate the effect of sulfate moieties in the extracellular microenvironment on mitogenicity and phenotype of chondrocytes. We established a 3D model based on sulfation of alginate, a biopolymer that lacks adhesion ligands and limits cell proliferation,[55] with tunable degree of modification, stiffness and hydrophilicity to elucidate how the sulfation of ECM components influences cellular responses.

2. Results

2.1. Biomimetic alginate sulfate hydrogels and their characterization

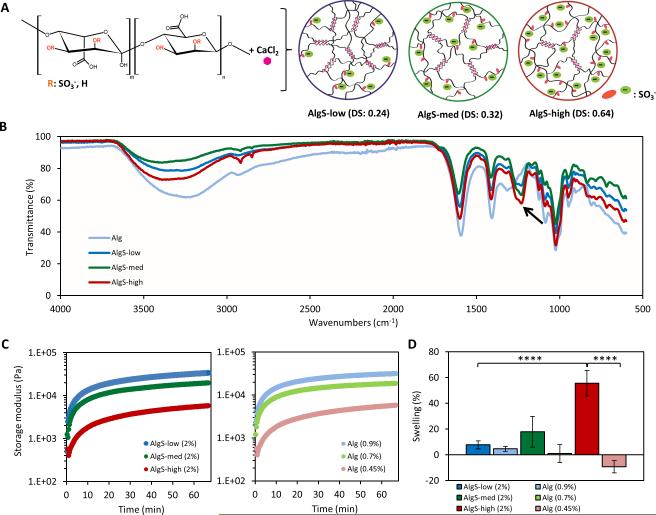

Sulfation of alginate (Alg) was carried out as previously reported[56] and tuned by varying the chlorosulfonic acid (HClSO3) concentration to yield low (AlgS-low), medium (AlgS-med), and high (AlgS-high) degree of sulfation (DS) (Figure 1A). Peaks characteristic to S=O stretching were confirmed with FTIR spectra at 1250 cm−1 and 1260 cm−1 for the sulfated alginates (Figure 1B) and elemental analysis was performed to obtain the sulfur content and calculate the DS (AlgS-low: DS=0.24; AlgS-med: DS=0.32; AlgS-high: DS=0.64 per monosaccharide) (Supporting Information , Figure S1A). Depolymerization was minimal and a slight decrease in average molecular weight (Mw) of alginate was measured with increasing DS indicated by a shift in the mass distribution chromatogram (Supporting Information, Figure S1B, C).

Figure 1.

Characterization of alginate sulfate hydrogels. (A) Chemical structure of modified alginate and scheme showing calcium crosslinking of alginate sulfate with increasing degree of sulfation. (B) FTIR spectra of alginate (pale blue), AlgS-low (blue), AlgS-med (green) and AlgS-high (red). Arrow indicates peaks characteristic to S=O stretching at 1250 cm−1 and 1260 cm−1. (C) Rheology profiles of alginate sulfate (dark blue, green and red) and alginate (pale blue, green, red) hydrogels showing storage modulus (E’) with time. (D) Percent mass swelling of alginate sulfate (dark blue, green and red) and alginate hydrogels (pale blue, green, red) after 48 hours. n=5; mean± s.d.; ****: p <0.0001 when compared to AlgS-high.

In situ rheological analysis revealed that, for a fixed polymer content of 2% (w/v), the storage modulus (E’) of AlgS hydrogels decreased from 34 to 6 kPa with increasing DS (Figure 1C). Above the DS of AlgS-high (0.64), alginate sulfate did not gel in the presence of CaCl2 (102 × 10−3 m). To obtain control samples having the same storage moduli as AlgS-low, -med and -high, unmodified alginate samples with polymer concentrations of 0.9, 0.7 and 0.45% w/v were used respectively (Alg-stiff, Alg-med, Alg-soft). Monitoring of the storage modulus over time confirmed almost identical gelation behavior between each AlgS sample and its unmodified alginate control (Figure 1C). Introduction of sulfate moieties caused an increase in the hydrophilicity of hydrogels as was expected from the higher negative charge. Mass swelling ratio of AlgS hydrogels increased with increasing DS, reaching 55% for the AlgS-high samples (Figure 1D). On the other hand, unmodified alginate hydrogels showed decreased swelling behavior with decreasing polymer content. Alg-stiff hydrogels exhibited ~5% swelling, Alg-med hydrogels preserved their mass whereas Alg-soft hydrogels showed ~10% shrinkage (Figure 1D).

To decouple the effects of sulfation from changes in swelling, polymer content and network porosity, we established two different approaches to systematically tune these parameters. In the first strategy, we changed the crosslinker to barium (Ba2+), which has higher affinity to alginate and thus reduces the swelling of AlgS-high hydrogels. Alginates with high guluronic acid composition have been reported to exhibit shrinking and loss of permeability[57] when crosslinked with Ba2+. Secondly, we functionalized alginate with acetyl groups[58] (Supporting Information, Figure S2A, B) to obtain hydrogels with comparable stiffness and swelling as alginate sulfate in the absence of negatively charged sulfate groups.

2.2. Sulfation of alginate promotes mitogenicity of chondrocytes in 3D

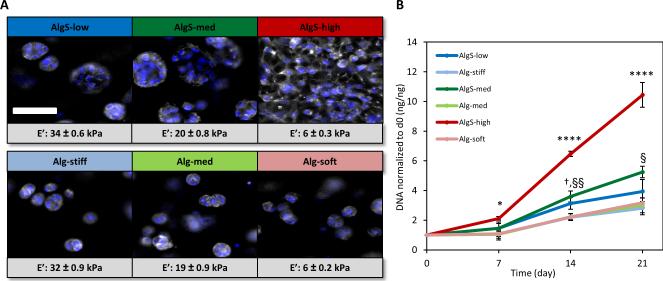

To explore the effects of sulfation on cell growth, we encapsulated freshly isolated bovine articular chondrocytes in AlgS and Alg hydrogels at a density of 6 × 106 cells mL−1 and cultured the samples up to 3 weeks. All sulfated and unmodified hydrogels supported very high chondrocyte viability (Supporting Information, Figure S3). Furthermore, phalloidin staining revealed distinct changes in cell morphology in sulfated hydrogels. As DS increased, chondrocytes exhibited a more spread morphology implying cellular recognition of and adhesion to the sulfated microenvironment (Figure 2A). This is an atypical behavior for cells in alginate hydrogels unless the hydrogel is modified by integrin-binding motifs such as RGD.[54] In line with our findings, alginate sulfate has been previously shown to induce spread morphology of chondrocytes mediated by integrin β1.[59] In contrast, alginate hydrogels with decreasing polymer content and stiffness did not support such cell spreading (Figure 2A).

Figure 2.

Proliferation of chondrocytes in alginate sulfate hydrogels. (A) Fluorescence imaging of phalloidin-rhodamine (gray) and DAPI (blue) stained aggregates of chondrocytes in alginate sulfate and alginate hydrogels, and proliferating chondrocytes throughout the entire hydrogel space in AlgS-high. Scale bar: 50 μm. (B) Quantification of DNA content in alginate sulfate and alginate hydrogels. DNA content at a given time point is normalized to the DNA content at day 0. n=3 (biological replicates); mean± s.d.; *: p< 0.05, ****: p <0.0001 for AlgS-high compared to other AlgS and Alg samples; §: p<0.05, §§: p< 0.01 for AlgS-med compared to Alg samples; †: p< 0.05 for AlgS-low compared to Alg samples.

Quantification of DNA content over 3 weeks revealed that sulfation of alginate potently promoted proliferation of chondrocytes in 3D (Figure 2B). Chondrocytes in sulfated hydrogels proliferated significantly more than in unmodified hydrogels and this mitogenic effect was found to increase with increasing sulfation. DNA content in AlgS-high hydrogels showed a more than 10 fold increase after 3 weeks which was significantly higher than AlgS-med and AlgS-low (p< 0.0001) hydrogels. On the other hand, chondrocyte growth was similar in all alginate gels independent of stiffness, suggesting that the mitogenic effects of the sulfated gels were due to the chemical modification (Figure 2B).

Although sulfated hydrogels and their unmodified alginate controls had matched bulk storage modulus, scanning electron microscopy (SEM) of the samples revealed that alginate sulfate samples had a higher porosity and a more open network structure due to higher swelling properties (Supporting Information, Figure S4A). To rule out that swelling and porosity were responsible for alterations in cell growth, we investigated proliferation of chondrocytes in alginate sulfate hydrogels crosslinked with barium (Ba2+) that do not show enhanced swelling behavior or porosity (Supporting Information, Figure S4B, C). Ba2+-crosslinked AlgS-high hydrogels highly stimulated mitogenicity of encapsulated chondrocytes compared to alginate (Supporting Information, Figure S4D). Quantification of cell growth with DNA content further confirmed that chondrocytes proliferated significantly more in AlgS-high hydrogels over 3 weeks than in alginate hydrogels pointing out that the effect of sulfation on proliferation was also independent of hydrophillicity of the gel network (Supporting Information, Figure S4E).

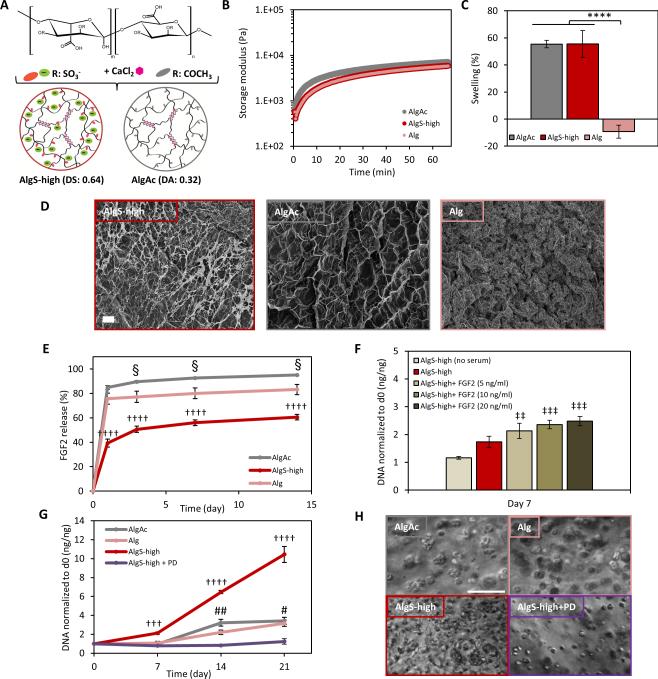

2.3. Chondrocyte growth in alginate sulfate hydrogels is mediated by entrapment of mitogenic growth factors

Next, we investigated whether chondrocyte proliferation in alginate sulfate hydrogels resulted from higher entrapment of mitogenic growth factors and their downstream signaling. Alginate sulfate has been previously shown to effectively bind to heparin-binding growth factors.[60] To account for differences in polymer content of alginate sulfate and alginate hydrogels that could affect the permeability of the gel network for growth factors and to better mimic the swollen state of sulfated hydrogels, we used acetylated alginate (Figure 3A). Acetylated alginate (AlgAc) served as a modified control for AlgS-high with similar stiffness, swelling behavior and porosity but without the charge-mediated affinity of sulfated hydrogels to growth factors (Figure 3B, C, D).

Figure 3.

Mitogenic activity in alginate sulfate hydrogels is mediated by FGF signaling. (A) Chemical structure of modified alginate with sulfate or acetyl groups and scheme showing calcium crosslinked modified hydrogels. (B) Rheological profiles of AlgS-high (dark red), Alg (pale red) and AlgAc (gray) hydrogels showing storage modulus (E’) with time. (C) Percent mass swelling of AlgS-high, Alg and AlgAc hydrogels after 48 hours. n=5; mean± s.d.; ****: p <0.0001 compared to Alg. (D) SEM images of freeze-dried AlgS-high, Alg and AlgAc hydrogels. Scale bar: 20 μm. (E) Percent cumulative FGF2 release from AlgS-high, Alg, and AlgAc hydrogels over 2 weeks. n=3; mean± s.d.; ††††: p< 0.0001 for AlgS-high compared to Alg and AlgAc; §: p< 0.05 for AlgAc compared to Alg. (F) Effect of FGF2 supplementation on chondrocyte growth in AlgS-high hydrogels. Quantification of DNA content of chondrocytes in growth medium, growth medium supplemented with 5, 10 or 20 ng mL−1 FGF2 or growth medium without serum. DNA content is normalized to the DNA content at day 0. n=3 (biological replicates); mean± s.d.; ‡‡: p< 0.01, ‡‡‡: p< 0.001 compared to no serum condition. (G) Quantification of DNA content of chondrocytes in Alg, AlgAc, AlgS-high hydrogels and in AlgS-high with 500 × 10−9 m FGF inhibitor (PD173074) in the medium. DNA content at a given time point is normalized to the DNA content at day 0. n=3 (biological replicates); mean± s.d.; †††: p<0.001, ††††: p<0.0001 for AlgS-high compared to Alg, AlgAc and AlgS-high with PD173074 treatment (AlgS-high+PD). #: p<0.05, ##: p<0.01 for AlgAc and Alg compared to AlgS-high+ PD. (H) Representative bright-field images of chondrocytes in AlgAc, Alg, AlgS-high and AlgS-high+PD after 21 days in culture. Scale bar: 100 μm.

We examined the growth factor binding and entrapment of AlgS-high, Alg-soft and AlgAc hydrogels. We loaded the gel precursor solutions with FGF2 (10 ng/gel) and monitored the release of FGF2 from the hydrogels for 2 weeks by enzyme linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). AlgS-high hydrogels showed a significantly lower cumulative release of FGF2 at all time points compared to the control AlgAc and Alg-soft hydrogels, and almost 40% of initially loaded FGF2 was retained in the AlgS-high hydrogels after 2 weeks (Figure 3E). FGF2 release from AlgAc hydrogels was significantly higher than Alg-soft hydrogels despite the higher polymer content, which could be attributed to the high swelling of AlgAc and shrinking of Alg-soft hydrogels and differences in permeability (Figure 3E). Similarly, the release of FGF2 from the swelling Alg-stiff hydrogels was similar to AlgAc hydrogels and was significantly higher than Alg-soft over 2 weeks. On the other hand, the FGF2 release profile of AlgS-low, AlgS-med and AlgS-high hydrogels were quite similar where increased swelling and permeability due to higher sulfation might have compromised for the higher affinity to the growth factor (Supporting Information, Figure S5).

After showing the entrapment of FGF2 in alginate sulfate hydrogels, we confirmed its mitogenic effects on primary chondrocytes. Reports of the effect of FGF2 on chondrocyte growth have been controversial where it has been shown to be both a potent mitogen for chondrocytes and growth inhibitory.[35,61-63] To test the growth factor dependence of chondrocyte proliferation in AlgS-high hydrogels, we first serum starved the chondrocytes. The cells no longer proliferated in AlgS-high hydrogels when the growth factors were depleted (Figure 3F). When serum-containing growth medium was further supplemented with FGF2, chondrocyte proliferation increased in a dose-dependent manner confirming the mitogenic effect of FGF2 on chondrocytes in AlgS-high hydrogels (Figure 3F). Chondrocyte growth in AlgS-high, AlgAc and Alg-soft hydrogels were monitored and quantified over 3 weeks (Figure 3G, H). AlgS-high hydrogels promoted proliferation of chondrocytes significantly higher than AlgAc hydrogels with the same polymer content, stiffness and swelling reflecting the effect of higher entrapment of mitogenic growth factors such as FGF2. On the other hand, cell yield was quite similar in AlgAc and Alg-soft hydrogels over 3 weeks. When chondrocytes were treated with an FGFR1/3 inhibitor (PD173074) to block FGF signaling, cell proliferation in AlgS-high hydrogels was completely lost and the cell number remained stable after 3 weeks of culture (Figure 3G, H and Supporting Information, Figure S6). These results clearly demonstrated the FGF signaling-mediated mitogenicity of chondrocytes in sulfated hydrogels.

2.4. Alginate sulfate mimics heparan sulfate/heparin to activate FGF signaling in chondrocytes

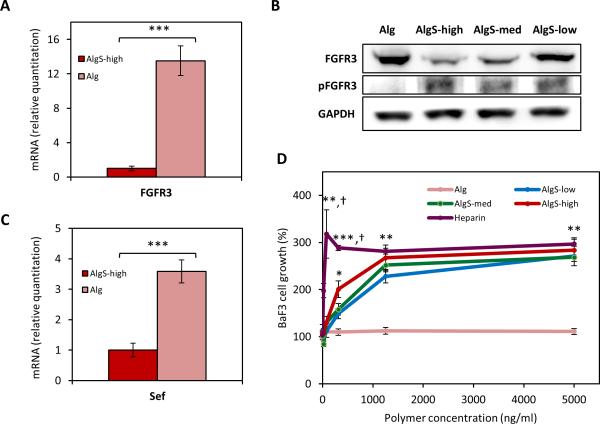

We next explored the regulation of FGF signaling by chondrocytes encapsulated in the sulfated hydrogels. In vivo, binding of FGFs to their receptor is mediated by heparan sulfates leading to the dimerization, phosphorylation, and activation of the receptor and initiation of downstream signaling events.[24,25] Therefore, we investigated the activation and expression of FGF receptors in the sulfated alginate hydrogels. Due to its relevance and importance in chondrogenesis and adult cartilage anabolism,[35] we sought to investigate the expression and signaling of FGFR3. Chondrocytes growing in AlgS hydrogels significantly downregulated FGFR3 gene (p<0.001) and protein expression compared to Alg hydrogels (Figure 4A, B, and Supporting Information, Figure S7A). Downregulation of FGFR3 expression on the gene and protein level upon FGF stimulation has been reported previously via a feedback inhibitory loop.[61] As increased chondrocyte proliferation in AlgS-high hydrogels was FGF-mediated, we hypothesized that the downregulation of FGFR3 was a feedback inhibitory response for the activation of the receptor. As expected, when the chondrocytes were treated with PD173074 and FGFR3 signaling was blocked, gene expression of FGFR3 in the AlgS-high hydrogels was rescued (Supporting Information, Figure S7B). Protein expression of FGFR3 showed a downregulation in AlgS hydrogels in a dose-responsive manner to the DS (Figure 4B). Most interestingly, the phosphorylated active form of the receptor was only detected in the sulfated gels indicating the necessity of a sulfated microenvironment for induction of downstream signaling (Figure 4B).

Figure 4.

Alginate sulfate mimics heparin to mediate an interaction between FGF2 and FGFR3 to induce down-stream signaling. (A) mRNA expression of FGFR3 of chondrocytes encapsulated in AlgS-high and alginate hydrogels after 7 days. (B) Immunoblot showing protein expression of FGFR3 and phosphorylated FGFR3 (phospho Y724) of chondrocytes in AlgS-low, AlgS-med, AlgS-high and alginate hydrogels. GAPDH was used as the endogenous loading control. (C) mRNA expression of Sef of chondrocytes encapsulated in AlgS-high and alginate hydrogels. (D) Proliferation of BaF3-FGFR31c cells with FGF2 (10−9 m) and soluble alginate, alginate sulfate or heparin (0-5000 ng mL−1). [3H]-thymidine incorporation (radioactivity counts per minute, c.p.m.) was normalized to the condition with no polymer addition. n=3; mean± s.d.; *: p<0.05, **: p<0.01, ***: p<0.001 compared to Alg sample. †: p<0.05 for heparin compared to AlgS samples.

A recently identified endogenous FGF signaling modulator, Sef (similar expression to FGF genes), has been shown to physically associate with FGF receptors and inhibit their tyrosine phosphorylation, and hence block downstream signaling.[64] Previous reports revealed its importance in skeletal growth as it was shown to negatively regulate osteogenesis and osteoprogenitor cell proliferation,[65] whereas its expression and regulation in chondrocytes is unknown. Remarkably, we observed that chondrocytes in AlgS hydrogels significantly downregulate Sef expression compared to Alg hydrogels (p<0.001) and prevent the attenuation of FGF signaling via Sef-mediated negative feedback inhibition (Figure 4C).

Distinct regulation of FGF signaling in AlgS hydrogels raised the question whether AlgS can mimic the function of heparan sulfate/heparin to mediate a ternary complex formation between the growth factor and its receptor. To test this hypothesis, we used a lymphoid cell line, BaF3-FGFR31c, which was engineered to express a chimeric protein containing the FGFR3 extracellular and transmembrane domain and FGFR1 tyrosine kinase domain, and lacked cell-surface heparan sulfates. The FGF-mediated growth of BaF3 cells depends on the addition of soluble heparin to activate the receptor.[66] We cultured the BaF3 cells in the presence of FGF2 and soluble heparin, AlgS, or Alg and monitored their growth at increasing polymer concentration up to 5 μg mL−1 (Figure 4D). All AlgS solutions, like heparin mediated the binding of FGF2 to FGFR3 and induced survival and proliferation of BaF3 cells, whereas Alg showed no activity. Below a polymer concentration of 1 μg mL−1, heparin and AlgS-high induced significantly higher cell growth than AlgS-low and AlgS-med, whereas at higher concentrations there was no difference between AlgS samples and heparin. These results confirm alginate sulfate as a heparin-mimetic biopolymer that can facilitate a complex formation between FGF2 and FGFR3 to stimulate mitogenicity.

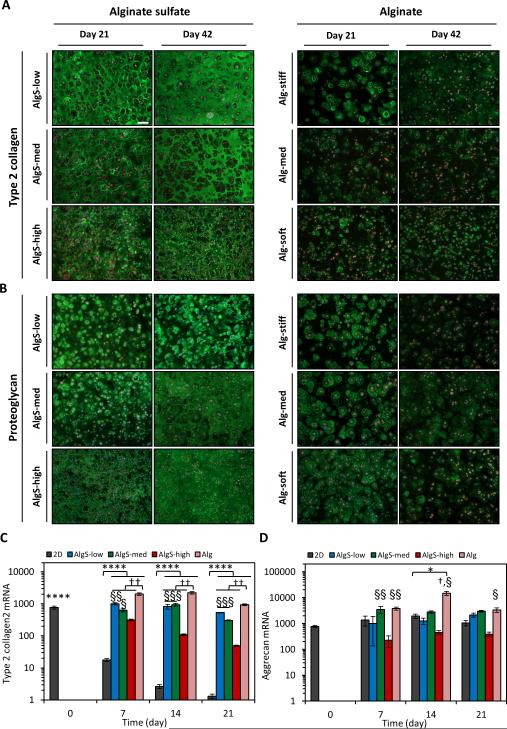

2.5. Chondrocytes growing in biomimetic sulfated hydrogels produce cartilage-specific matrix

Type 2 collagen (Col2) and proteoglycans comprise the main components of the cartilage ECM.[17] As chondrocytes proliferate on 2D substrates, they lose the expression of these chondrogenic markers and undergo de-differentiation.[53,54] Therefore, after showing the potent proliferation capacity of freshly isolated chondrocytes in 3D in the biomimetic alginate sulfate hydrogels, we next examined how the sulfated microenvironment affected their production of cartilage matrix. Immunostaining results revealed strikingly higher amounts of Col2 and proteoglycan deposition in the alginate sulfate hydrogels compared to alginate (Figure 5A, B). Col2 and proteoglycan deposition was very homogeneous throughout the alginate sulfate hydrogels whereas only pericellular staining could be detected in the alginate. Col2 deposition was higher in the AlgS-low hydrogels than AlgS-med and AlgS-high while proteoglycan deposition was higher in the higher sulfated hydrogels. Matrix deposition in the alginate sulfate hydrogels increased even further from 3 weeks to 6 weeks whereas such maturation was not observed in the alginate hydrogels. Moreover, proteoglycan deposition diminished in the alginate hydrogels between 3 and 6 weeks of culture (Figure 5B). Gene expression analysis showed that growth of chondrocytes in 3D hydrogels prevented them from losing their gene expression of Col2 as opposed to 2D expansion (Figure 5C). Over 3 weeks, Col2 expression in all hydrogels was significantly higher than in chondrocytes which proliferated on 2D. On the other hand, chondrocytes had higher Col2 gene expression in alginate hydrogels than alginate sulfate at all time points. Furthermore, AlgS-low and AlgS-med hydrogels induced higher expression compared to AlgS-high hydrogels. This could be due to decreased stiffness[67] among alginate hydrogels, as chondrocytes also tended to have higher expression of Col2 in stiffer hydrogels (Supplementary Information, Figure S8). The gene expression of the most abundant proteoglycan in cartilage, aggrecan, was stable during 2D expansion of chondrocytes in line with previous reports[54] (Figure 5D). Aggrecan expression, similar to Col2, was higher in chondrocytes growing in alginate hydrogels than in alginate sulfate. Although chondrocytes had higher gene expression of both chondrogenic markers in Alg hydrogels, alginate sulfate hydrogels had much stronger staining for chondrogenic markers. Therefore, we further explored the extent of de-differentiation and catabolic activity of chondrocytes in alginate and alginate sulfate hydrogels.

Figure. 5.

Alginate sulfate hydrogels promote deposition of cartilage matrix components. (A, B) Immunofluorescence imaging of Col2 (green) (A) and proteoglycan (green) (B) antibody staining of chondrocytes encapsulated in AlgS (left) and Alg (right) hydrogels after 21 and 42 days of culture. Phalloidin-rhodamine (red) and DAPI (blue) was used as counterstains. (C, D) mRNA expression of Col2 (C) and aggrecan (D) of chondrocytes expanded on 2D or encapsulated in alginate sulfate and alginate hydrogels over 3 weeks of culture. n=3; mean± s.d.; *: p<0.05, ****: p<0.0001 compared to 2D expansion at day 7, 14 or 21; †: p<0.05, ††: p<0.01 compared to AlgS hydrogels. §: p<0.05, §§: p<0.01, §§§: p<0.001 compared to AlgS-high. Scale bar: 100 μm.

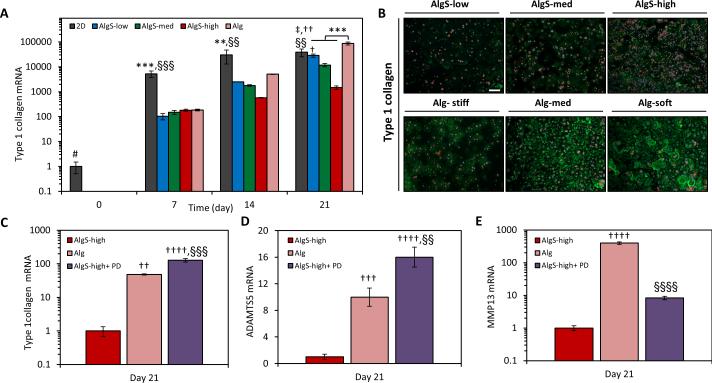

2.6. Sulfation in the microenvironment lowers the extent of chondrocyte de-differentiation

Loss of phenotype in chondrocytes or de-differentiation due to 2D expansion is accompanied by upregulation of fibroblastic markers such as type 1 collagen (Col1)[53, 54] and is a main concern for autologous chondrocyte-based cartilage therapies. Hence, the course of de-differentiation as freshly isolated chondrocytes proliferate within a mitogenic 3D environment is of particular interest. As expected, chondrocytes cultured on 2D tissue culture polystyrene underwent a massive increase in Col1 expression (~40’000 fold) over 3 weeks. At day 7, Col1 expression of chondrocytes in alginate and alginate sulfate hydrogels was much less compared to 2D, however by day 21, chondrocytes in alginate showed even higher expression of Col1 than chondrocytes expanded on 2D. Significantly, chondrocytes in alginate sulfate hydrogels had ~50 fold lower expression of Col1 compared to alginate, indicating the sulfated microenvironment led to a better preservation of phenotype in the chondrocytes (Figure 6A). These results were confirmed by immunostaining, which showed that chondrocytes deposited considerably less Col1 in the biomimetic sulfated hydrogels (Figure 6B). The Col1 gene expression decreased in alginate sulfate hydrogels in a DS dependent manner pointing to a possible effect of enhanced FGF signaling in preserving the native phenotype of chondrocytes. FGF2 supplementation during 2D expansion has been reported to reduce de-differentiation of chondrocytes,[62] maintain the chondrogenic potential and improve the re-differentiation in 3D scaffolds.[63] Thus, we treated the chondrocytes growing in AlgS-high hydrogels with PD173074 to explore the role of FGF signaling in the preservation of phenotype. When FGF signaling was blocked, chondrocytes upregulated Col1 expression in AlgS-high hydrogels to an even higher extent than in alginate (Figure 6C). This demonstrates that biomimetic hydrogels not only exert mitogenicity on chondrocytes but also maintain their phenotype, likely through mediation of FGF binding to its receptor and initiation of signaling. FGF signaling has been shown to have a chondroprotective and anabolic role in cartilage tissue through activation of FGFR3 with FGF18 and FGF2 whereas it can also induce catabolic destruction of the cartilage ECM via activation of FGFr1 and upregulation of MMP13 and ADAMTS5.[35,37,39,40] Chondrocytes in AlgS hydrogels significantly downregulated the expression of ADAMTS5 (p<0.001) (Figure 6D), the dominant aggrecanase in cartilage, and MMP13 (p<0.0001) (Figure 6E), a matrix metalloproteinase with specificity to aggrecan and fibrillar collagen, compared to chondrocytes in alginate hydrogels.[4,36] Downregulation of these catabolic markers correlates well with the activation of FGFR3 signaling in the AlgS hydrogels. Chondrocytes treated with PD173074 in AlgS-high hydrogels lose their suppression of ADAMTS5 which further supports the chondroprotective role of FGF signaling[39] (Figure 6D). Chondrocytes in Alg showed ~400 fold upregulation of MMP13 expression compared to AlgS-high. When FGFR3 was blocked with PD173074 in AlgS-high hydrogels, chondrocytes slightly upregulated MMP13 expression but still significantly lower than in Alg hydrogels indicating there might be other pathways contributing to the strong suppression of this catabolic marker in alginate sulfate hydrogels (Figure 6E). Furthermore, such upregulation of MMP13 and ADAMTS5 could explain the Col2 and proteoglycan loss in the alginate hydrogels despite of the high gene expression (Figure 5).

Figure 6.

Alginate sulfate hydrogels suppress the expression of de-differentiation and catabolic markers in chondrocytes. (A) mRNA expression of Col1 of chondrocytes expanded on 2D or encapsulated in alginate sulfate and alginate hydrogels over 3 weeks of culture. (B) Immunofluorescence imaging of Col1 (green) antibody staining of chondrocytes encapsulated in AlgS and Alg hydrogels after 21 days. Phalloidin-rhodamine (red) and DAPI (blue) was used as counterstains. Scale bar: 100 μm. (C, D, E) mRNA expression of collagen 1 (C), ADAMTS5 (D), MMP13 (E) of chondrocytes encapsulated in Alg, AlgS-high and AlgS-high with PD173074 treatment (500 10−9 m) after 21 days. n=3; mean± s.d.; **: p<0.01, ***: p<0.001 compared to AlgS hydrogels; †: p<0.05, ††: p<0.01, †††: p<0.001, ††††: p<0.0001 compared to AlgS-high. ‡: p<0.05 compared to AlgS-med. §§: p<0.01, §§§: p<0.001, §§§§: p<0.0001 compared to Alg. #: p<0.05 for 2D at day 0 compared to later time points.

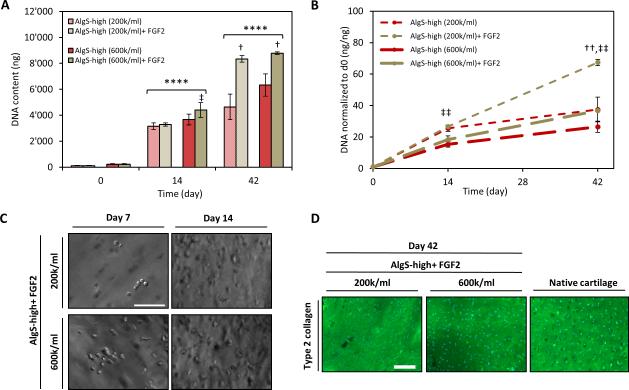

2.7. Alginate sulfate hydrogels support proliferation of chondrocytes encapsulated at a clinically-relevant low cell density

As biomimetic AlgS hydrogels provide a mitogenic and chondrogenic microenvironment for chondrocytes and promote their self-renewal in 3D, they present a promising platform for encapsulating and expanding freshly isolated chondrocytes. Since the yield of autologous cells is generally quite low from a clinical biopsy, biomimetic hydrogels could serve a great need in supporting the self-renewal of chondrocytes.[52] We thus tested if alginate sulfate hydrogels could generate clinically significant amounts of cells starting from a very low cell density.

We encapsulated non-passaged chondrocytes in AlgS-high hydrogels at a density of 2 × 105 or 6 × 105 cells mL−1 and monitored their growth over 6 weeks in culture. We further tested the effect of FGF2 loading of the hydrogels to increase the mitogenic potential of the cells and take advantage of the availability of the affinity-bound growth factors in a clinical-like setting. AlgS-high hydrogels induced potent proliferation of chondrocytes with both starting cell densities. By day 14, significant increase in cell number was observed as well as complete and homogenous filling of the hydrogels with matrix proteins (Figure 7A, B, C, D). After 6 weeks, there was not a significant difference in the cell yield between the two starting cell densities (Figure 7A). Moreover, FGF2 loading of the hydrogels significantly increased the proliferation of chondrocytes and led to a significantly higher DNA content for both cell densities at 6 weeks (Figure 7A, B). The lower starting cell density and higher population doubling did not negatively affect the cartilage matrix production and chondrocytes deposited great amount of Col2 in AlgS-high hydrogels with both cell densities (Figure 7D).

Figure 7.

Alginate sulfate hydrogels support the growth of chondrocytes encapsulated at clinically-relevant low density. (A) Quantification of DNA content of chondrocytes encapsulated in AlgS-high hydrogels at a density of 2 × 105 or 6 × 105 cells mL−1 with (tan) or without (red) FGF2 loading. (B) DNA content normalized to the DNA content at day 0. n=3; mean± s.d.; ****: p<0.0001 compared to day 0; †: p<0.05, ††: p<0.01 compared to without FGF2-loading; ‡‡: p<0.01 for 2 × 105 cells mL−1 compared to 6 × 105 cells mL−1. (C) Representative bright-field images of chondrocytes in FGF2-loaded AlgS-high hydrogels at 2 × 105 or 6 × 105 cells mL−1 density. Scale bar: 100 μm. (D) Immunofluorescence imaging of Col2 (green) antibody staining of chondrocytes encapsulated in FGF2-loaded AlgS-high hydrogels at 2 × 105 or 6 × 105 cells mL−1 density at day 42. DAPI (blue) was used as counterstain. Native bovine cartilage was stained as positive control. Scale bar: 100 μm.

The fold change in DNA interestingly exhibits an increase with decreasing cell density for a defined volume of hydrogel revealing higher growth rate when the cell number is lowered (Figure 7B). This implies that the mitogenicity results mainly from the signaling events induced by the hydrogel microenvironment and the effects of intercellular distances or paracrine signaling are not pronounced. There is a more than 65 fold increase in DNA after 6 weeks from a starting cell density of 2 × 105 cells mL−1 which to our knowledge presents an extent of mitogenicity that has never been reported for 3D growth of cells in hydrogels. Such potent stimulation of proliferation with a simple modification of a biopolymer indicates the importance of mimicking salient features of the native ECM and shows a strong potential for clinical usage.

3. Discussion

The physical and chemical characteristics of the ECM microenvironment play a vital role in tissue-specific biological function, hence providing inspiration for the design of mimetic materials for tissue engineering and regenerative medicine. In this work, we address sulfation as an important feature of the ECM contributed by the proteogylcans and demonstrate its potent effect on chondrocytes, a cell type that resides in a glycosaminoglycan-rich, highly sulfated tissue. Using alginate with tunable degree of sulfation, we demonstrate that biomimicking the ECM microenvironment through incorporation of sulfate moieties regulates mitogenicity of chondrocytes and preservation of chondrogenic phenotype.

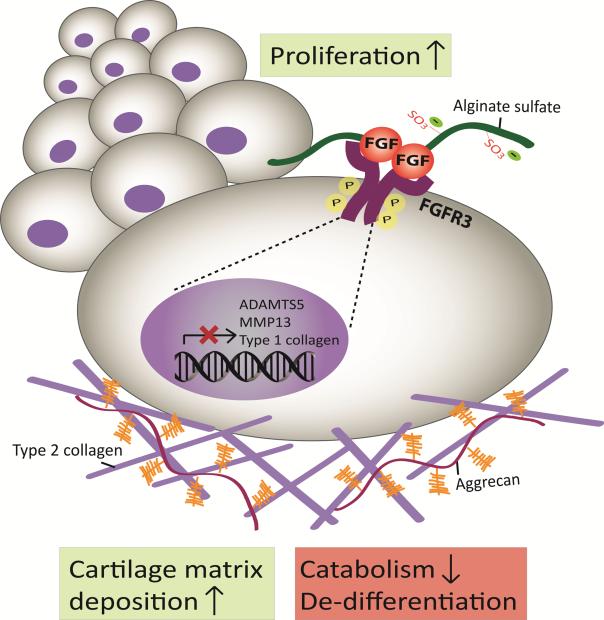

Sulfation of alginate greatly promotes proliferation of chondrocytes in a 3D matrix independent of biophysical properties including stiffness, swelling and porosity. The biomimetic alginate sulfate hydrogels confer high affinity to mitogenic growth factors such as FGF2 and mediate a HS/heparin-like interaction between the growth factor and its receptor to initiate downstream signaling events. Such interaction between FGFs and their receptors mediated by HS/heparin is crucial for the activation of the receptor; hence the ECM dynamically contributes to the signaling events in the cells.[25,38] Alginate sulfate hydrogels similarly stimulate activation of FGFR3 in chondrocytes, which is an important FGF receptor for cartilage anabolism. Thus, they demonstrate the unique ability of a biomimetic 3D matrix to control activation of specific growth factor receptors and downstream cellular responses. FGFR3 signaling induced by FGF2 and FGF18 has been coupled with chondrogenic and anabolic responses in chondrocytes, however, it has been shown to have paradoxical roles in mitogenicity in the growth plate, both promoting and inhibiting chondrocyte proliferation depending on the stage of cartilage development.[35,68] We revealed that sulfation in the microenvironment induces proliferation of freshly isolated mature chondrocytes, stimulate cartilage matrix deposition and suppress expression of markers of de-differentiation and catabolism via activation of FGF signaling (Figure 8).

Figure 8.

Schematic depiction of the mechanism of activation of FGF signaling in alginate sulfate hydrogels. Alginate sulfate mimics heparan sulfate proteogylcans to exert high affinity for FGFs and mediates an interaction between the growth factor and its receptor leading to activation of the receptor and initiation of downstream signaling. Activation FGF signaling in chondrocytes mediated by the sulfated microenvironment promotes potent proliferation, cartilage matrix deposition and suppression of de-differentiation and catabolism.

In the native cartilage tissue, FGFs are produced endogenously and sequestered by the heparan sulfate proteoglycans in the pericellular matrix such as perlecan to regulate chondrogenic responses.[42,44-46] Moreover, FGF2 has been shown to stimulate Sox9, the main transcription factor driving the expression of cartilage matrix components.[69] FGF2 has also been shown to act as a chondroprotective agent to suppress the expression of catabolic markers such as ADAMTS5.[39] In line with these reports, we found that increased sulfation in the microenvironment suppresses the expression of ADAMTS5 and MMP-13 in chondrocytes via activation of FGF signaling. These results interestingly point to the role of the ECM composition on the phenotype of chondrocytes as well as the way they remodel and degrade the surrounding matrix. This is particularly important for better understanding of pathological conditions such as osteoarthritis where loss of proteoglycans is the first detectable change in the articular cartilage surface and its absence may elicit increased catabolic activity of chondrocytes and start the downwards spiral of tissue destruction.

Collectively, we demonstrate that the sulfation state of the surrounding microenvironment modulates self-renewal of chondrocytes defined by stimulation of proliferation and preservation of chondrogenic phenotype. This not only exhibits that the ECM dynamically regulates signaling of chondrocytes but also challenges the dogma that increased chondrocyte proliferation is accompanied by dedifferentiation and loss of phenotype. We show that sulfation of alginate, a biopolymer known to limit cell proliferation, confers mitogenicity and promotes potent proliferation of encapsulated non-passaged chondrocytes within a 3D matrix. Alginate sulfate hydrogels support the growth of chondrocytes with very low starting cell densities and the extent of proliferation achieved in this study has not been reported for hydrogels. Hence, such sulfated mitogenic hydrogels could be promising for 3D expansion of many cell types where loss of cell potency during the 2D expansion phase negatively impacts the outcome of cell-based therapies. However, for the clinical translatability of the technology, the hydrogels should be characterized for loading with a serum-free and defined growth factor cocktail that has been optimized for the cell type of interest.

Sulfated alginate also presents a heparin-mimetic which mediates activation of distinct growth factor signaling events in chondrocytes. Given the disadvantages of using heparin[29,30,33] such as heterogeneity and fast degradation alginate sulfate offers a promising alternative. Growth factor signaling is crucial for many cell types and multiple cellular processes including differentiation, migration and proliferation. Therefore, approaches comprising incorporation of heparin into materials to increase affinity to growth factors,[29,30] protein engineering to enhance affinity of growth factors to ECM components[70] or immobilization of growth factors to matrices[5] have been actively pursued. Here, we show that sulfation in the ECM not only confers higher entrapment but also actively participates in the signaling through mediation of the interaction of growth factors with their receptors.

The desire to incorporate some of the complexity of the tissue-specific ECM into engineered tissues has given rise to techniques such as decellularization of native ECM,[71] anchoring of cell-derived ECM[72,73] and microarray screening of ECM components.[74] However, difficulties in experimental modulation of native ECMs still reveal the necessity of deciphering the distinct roles of ECM components in order to effectively recapitulate them in synthetic platforms. Finally, this study reveals that sulfation contributes to the active role of ECM in cellular signaling events and thus presents an important parameter to incorporate in engineering biomimetic materials.

4. Conclusions

The study demonstrates that sulfation of the cellular microenvironment is crucial for the mitogenicity and phenotype preservation of chondrocytes. Through controlled sulfation of an inert biopolymer such as alginate, extensive chondrocyte proliferation was induced independent of hydrogel stiffness, swelling and porosity. The mitogenicity within the sulfated hydrogels is shown to result from matrix-mediated activation of FGF receptors and downstream signaling leading to cartilage matrix formation and suppression of de-differentiation. This involvement of the sulfated hydrogel matrix in the growth factor signaling to exert desired cellular functions presents an essential aspect for mimicking native tissues with biomaterials and has broad implications for regenerative medicine.

5. Experimental Section

Modification of alginates

Sulfation of alginate (Pronova UP LVG, FG=0.67, NG<1=14, Novamatrix), was carried out as previously described. Briefly, 99% chlorosulfonic acid (HClSO3) (Sigma) was diluted in formamide (Sigma) at varying concentrations (2% for AlgS-low, 2.25% for AlgS-med, 2.5% for AlgS-high) with a total volume of 40 mL and added dropwise onto 1 g alginate. The reaction took place at 60 °C with agitation for 2.5 hours. Sulfated alginate was precipitated with cold acetone and centrifuged at 5000 rpm for 7 minutes followed by dissolution in deionized water. pH was adjusted to neutral by addition of 5 m NaOH during dissolution of sulfated alginate. Samples were purified by dialyzing against 100 × 10−3 m NaCl and then deionized water and lyophilized. For acetylation, alginate (LF10/60, FG=0.68, NG<1= 14, Protan A/S, Norway) beads were prepared by dripping a 2% (w/v) alginate solution into 100 × 10−3 m CaCl2. To remove the water, the beads were stored in pyridine for 24h, before suspending the beads in a 1:1 solution of pyridine-acetic acid anhydride at 38 °C for 12h. Gel beads were washed and dissolved in 0.05 m EDTA, followed by dialysis and lyophilization of the acetylated alginate.

Chemical characterization of modified alginates

Sulfation of alginate was confirmed using an infrared spectrophotometer in attenuated total internal reflection mode (Frontier Spectrometer ATR-FTIR, Perkin Elmer, Waltham, MA, USA) with spectra taken at room temperature (RT) in the range 600 cm−1 to 4000 cm−1. Elemental analysis of sulfur content was done by high-resolution inductively coupled mass spectrometry (HR-ICP-MS) on alginate dissolved in 0.1 m HNO3. Degree of sulfation (DS), number of sulfate groups per monomer, was estimated from the mass balance equation assuming one sodium counterion for each negatively charged group and one water molecule per monosaccharide: Monosaccharide mass= C6O6H5 + (DS+1)Na+ + (DS) SO3− + H2O. Acetylation of alginate was characterized by 1H NMR (Bruker) by dissolving the samples in D2O. Degree of acetylation (DA) was calculated from the ratio of the integral area of the protons attributed to the acetyl peak (δ =2-2.4 ppm). Molecular weight of the modified alginates was analyzed by size exclusion chromatography with a multiangle laser light (SEC-MALLS) detection system. A refractive index (dn/dc) of 0.15 was used for all the samples.

Rheological analysis of hydrogels

Dynamic oscillatory measurements were performed using an Anton Paar MCR 301 rheometer with parallel plate geometry (diameter: 10 mm). Alginate solution was pipetted on the plate and adjusted to a 0.5 mm gap. CaCl2 or BaCl2 solutions were added around the sample and the measurement was started. Storage (E’) and loss (E”) moduli were monitored with time under 0.5-5% strain and 1 Hz at RT. All measurements were done within the linear viscoelastic range (LVR). The measurements were repeated at least three times to ensure reproducibility of the gelation curves. The storage moduli of the gels were reported as mean ± s.d. for n=3.

Swelling of hydrogels

50 μl of alginate, alginate sulfate or acetylated alginate solutions were pipetted onto a disc caster (QGel SA) with 1.5 mm width. The caster was dipped into 102 × 10−3 m CaCl2 or 10 × 10−3 m BaCl2 for 20 minutes. The gels were weighed to obtain the initial weight (Mi) and then incubated in 1 ml of 150 × 10−3 m NaCl containing 5 × 10−3 m CaCl2 for 24 and 48h at 37 °C. The buffer was completely removed at each time point and the gels were weighed to obtain the swollen weight (MS). Swelling ratio was expressed as percent change in mass (%) = (MS- Mi)/Mi*100 and as mean± s.d. for n=5 gels.

Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM)

30 μl of alginate, alginate sulfate or acetylated alginate solutions were casted and gelled in 102 × 10−3 m CaCl2 or 10 × 10−3 m BaCl2 for 20 minutes. The hydrogels were swollen in 150 × 10−3 m NaCl containing 5 × 10−3 m CaCl2 overnight, fractured and snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen and lyophilized. Lyophilized samples were imaged with SEM (LEO 1530) at an operating voltage of 3-5 kV. All samples were sputter-coated with a gold/palladium alloy at 25 mA current for 60s before imaging.

Enzyme Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA) for quantification of FGF2 release

10 ng FGF2 (Peprotech) was mixed with hydrogel precursor solutions and incubated at RT for 1h. 2% (w/v) final concentration was used for sulfated and acetylated alginate samples whereas the concentrations of alginate solutions were 0.45, 0.7 and 0.9% (w/v). 30 μl discs from each solution were casted and gelled in 102 × 10−3 m CaCl2 for 20 minutes. Hydrogels were incubated in a buffer containing 150 × 10−3 m NaCl, 5 × 10−3 m CaCl2 and 0.1% (w/v) bovine serum albumin (BSA) (Sigma) up to 2 weeks. At given time points, the buffer was replaced completely and stored at −20 °C until used. After two weeks, the gels were dissolved by incubating in a buffer containing 0.055 m sodium citrate, 0.03 m EDTA and 0.15 m NaCl at pH 6.8 for 15 min with shaking at 1000 rpm at RT. FGF2 release from hydrogels as well as FGF2 retention in the hydrogels was quantified by an FGF2 ELISA kit (R&D Systems) according to manufacturer's protocols.

Chondrocyte isolation and encapsulation in hydrogels

Chondrocytes were isolated from the knees of 1-2 year old cows obtained from the local slaughterhouse. Articular cartilage was shaved from the condyles and minced with a sterile blade and washed with DMEM (Glutamax, high glucose) (Invitrogen) supplemented with 1% penicillin-streptomycin (P/S) (Gibco). Minced cartilage tissue was digested with 0.1% collagenase (Sigma) in DMEM supplemented with 5% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Invitrogen, 10270106, Lot# 41A0140K, 42F9251K) for 5h at 37 °C with gentle shaking. Digested tissue was filtered through a 100 μm and then a 40 μm cell strainer. The filtered solution of chondrocytes was centrifuged at 500 g for 10 min and washed twice with DMEM containing 10% FBS and 50 μg mL−1 L-Ascorbic acid -2-phosphate (Sigma). For 2D expansion, isolated chondrocytes were seeded at a density of 5000 cells cm−2 and passaged at 80-90% confluency up to three passages. For 3D growth, freshly isolated chondrocytes were encapsulated in the alginate hydrogels at a final density of 2 × 105, 6 × 105 or 6 × 106 cells mL−1. Gel precursor solutions of alginate, alginate sulfate and acetylated alginate were sterile filtered (0.2 μm pore size) and mixed with the concentrated chondrocyte suspension. 30 μl discs at indicated polymer concentrations were casted and gelled in 102 × 10−3 m CaCl2 or 10 × 10−3 m BaCl2 for 20 minutes. Chondrocytes encapsulated in hydrogels were cultured in growth medium containing DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS, 1% P/S, 50 μg/ml L-Ascorbic acid -2-phosphate and 3 × 10−3 m CaCl2 up to 6 weeks. To assess the mitogenic effect of FGF2 on chondrocytes, growth medium was further supplemented with 5, 10 and 20 ng mL−1 FGF2. For the inhibition of FGF signaling, PD173074 (500 × 10−9 m) was added to the growth medium up to 3 weeks. For the FGF2 loading of the gels, FGF2 was mixed with the alginate solutions (10 ng/30 μl disc) and cell suspension at indicated polymer concentrations and cell densities, followed by gelation in 102 × 10−3 m CaCl2 and culturing in growth medium up to 6 weeks.

Assessment of chondrocyte viability and morphology

Cell viability was assessed with a commercial live/dead kit (Invitrogen). Briefly, the gels were incubated in growth medium supplemented with 2 × 10−6 m calcein AM and 4 × 10−6 m ethidium homodimer for 1h at 37 °C. Then the gels were washed twice with growth medium for 20 min and imaged with fluorescence microscopy (Zeiss Axio Observer). For assessment of cell morphology, the gels were fixed with 4% formaldehyde (Sigma) with 0.1% Triton-X (Sigma) in PBS for 1h at 4 °C, washed twice with 150 × 10−3 m NaCl and 5 × 10−3 m CaCl2, stained with phalloidin-rhodamine for actin and DAPI for DNA and imaged with fluorescence microscopy.

Quantification of DNA content in the hydrogels

At each time point, hydrogels were washed twice with 150 × 10−3 m NaCl and 5 × 10−3 m CaCl2 and stored at −80 °C until all samples were collected. Then, the hydrogels were digested with 125 μg mL−1 papain (Sigma) in 10 × 10−3 m EDTA, 100 × 10−3 m sodium phosphate, 10 × 10−3 m L-cysteine at pH 6.3 overnight with shaking at 1000 rpm and 60 °C. DNA content in the digested samples was quantified with Quant-IT PicoGreen kit (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's protocol. Experiments were done with three biological replicates and triplicates of gels for each donor.

BaF3 cell culture and proliferation

BaF3 cells were washed twice in growth medium (RPMI, 10% bovine calf serum, L-Glutamine) and seeded with a density of 3 × 104 cells/well in a 96-well microtiter plate in 200 μl growth medium containing FGF2 (10−9 m) and heparin, alginate sulfate or alginate at indicated concentrations. 36 hours after cell seeding, 1 μCi of [3H] thymidine was added in each well in 50 μl growth medium. Cells were collected after 4-6 hours with a PHD cell harvestor (Cambridge Technologies Inc.). Liquid scintillation counting (LKB) was used to determine the thymidine incorporation.

Western blotting

At given time points, hydrogels washed twice with 150 × 10−3 m NaCl and 5 × 10−3 m CaCl2 and stored at −80 °C. The frozen hydrogels were homogenized with a pestle in RIPA buffer with protease (Sigma) and phosphatase (Invitrogen) inhibitors and incubated on ice for 1h followed by centrifugation at 10’000 g for 15min and collection of the supernatant. The protein concentration in the supernatant was determined by Bradford assay (Bio-Rad). Samples were adjusted to 1 μg μL−1 concentration with RIPA and Laemmli buffer and denatured at 95 °C for 5 min. 20 μg protein was loaded in pre-casted 4-12% Bis-Tris gels (Invitrogen) and run for 35 min at 125 V followed by transferring onto a nitrocellulose membrane for 1h at 25 V. Membrane was washed twice with ddH2O, stained with Ponceau S (Sigma) for protein visualization and washed three times with TBST buffer. The membrane was blocked with 5% BSA for 1h at RT and incubated with primary antibody overnight at 4 °C. After four times washing with TBST, the membrane was incubated with the secondary antibody for 1h at RT, washed again and visualized with Clarity Western ECL Substrate (Bio-Rad) for chemiluminescence. The primary antibodies used were anti-FGFR3 (Abcam), anti-FGFR3 (phospho Y724) (Abcam) and anti-GAPDH (Cell Signaling). The secondary antibody was anti-rabbit-HRP (Cell Signaling).

Real-time PCR

Samples were collected (three gels per condition) at day 7, 14 and 21 and frozen in liquid nitrogen. The hydrogels were homogenized with a tissue pestle in Trizol® (Invitrogen), centrifuged at 12’000 g for 10 min at 4 °C. The supernatant was phase separated with chloroform and centrifuged 12’000 g for 15 min at 4 °C and the aqueous phase was taken carefully. RNA isolation was performed using the NucleoSpin miRNA kit (Macherey-Nagel AG) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Quantification of RNA concentration was performed with a plate reader (Tek3 plate, Synergy, BioTek, Inc.). RNA was reverse transcribed using SuperScript III reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen) and cDNA was amplified by quantitative real-time PCR (StepOnePlus, Applied Biosystems) with Fast SYBR® Green master mix (Invitrogen). Ribosomal protein L13 (RPL13a) was used as an internal reference gene and fold change was quantified with the ΔΔCt method. The following primers for bovine (Microsynth AG) were used in this study: RPL13a (forward (F) 5’-GCCAAGATCCACTATCGGAAA-3’; reverse (R) 5’- AGGACCTCTGTGAATTTGCC-3’), COL2A1 (Col2) (F, 5’-GGCCAGCGTCCCCAAGAA-3’; R, 5’-AGCAGGCGCAGGAAGGTCAT-3’), ACAN (aggrecan) (F, 5’-GGGAGGAGACGACTGCAATC-3’; R, 5’-CCCATTCCGTCTTGTTTTCTG-3’), COL1A2 (Col1) (F, 5’-CGAGGGCAACAGCAGATTCACTTA-3’; R, 5’-GCAGGCGAGATGGCTTGTTTG-3’), FGFR3 (F, 5’- CTGTACGTGCTGGTGGAGTA-3’; R, 5’- GCAGGTGTCGAAGGAGTAGT-3’); SEF (F, 5’-TTCGGGTCATACTGGAGGAG-3’; R, 5’- GCTACTGTTGAGCTGCTTCG-3’); MMP13 (F, 5’-AAACATCCCAAAACGCCAGACAA-3’; R, 5’-AGGATGCAGCCG CCAGAAGA-3’); ADAMTS5 (F, 5’-GATGGTCACGGTAACTGTTTGCT-3’; R, 5’-GCCGGGACACACCGAGTAC-3’). Experiments were done with three biological replicates and three gels were pooled for each condition for all donors.

Immunohistochemisty

After 3 or 6 weeks of culture, hydrogels were fixed with 4% formaldehyde (Sigma) with 0.1% Triton-X (Sigma) in PBS for 1h at 4 °C and washed twice with 150 × 10−3 m NaCl and 5 × 10−3 m CaCl2. Then, hydrogels were incubated in a 1:1 mix of PBS and optimum cutting temperature compound (OCT, VWR) for 2h at RT followed by overnight embedding in OCT. Then the samples were snap-frozen on dry ice and 5 μm sections were cut with a cryotome (CryoStar NX70, ThermoScientific). The sections were fixed in ethanol, washed in PBS, blocked with 5% BSA for 1h at RT and incubated with primary antibody in 1% BSA overnight at 4 °C. For the staining against proteoglycans, special epitope retrieval was performed prior to BSA blocking. The sections were incubated with 10 × 10−3 m dithiothreitol (DTT) (Sigma) in 50 × 10−3 m Tris-HCl and 200 × 10−3 m NaCl (pH 7.4) for 2h at 37 °C and then alkylated with 40 × 10−3 m iodoacetamide in PBS for 1h at 37 °C. Then, the sections were digested with chondroitinase ABC (0.2 U mL−1) (Sigma) for 20 min at 37 °C. Followed by primary antibody incubation, the sections were washed three times in PBS, incubated with the secondary antibody in 1% BSA (IgG goat antimouse AlexaFluor 488, Invitrogen) for 1h at RT, washed again and incubated with phalloidin-rhodamine and DAPI in PBS for 15 min at RT. Then, the sections were covered with a coverslip with aqueous mounting media (Vector Laboratories) and imaged with fluorescence microscopy. The primary antibodies used were anti-Col2 (II-II6B3, Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank (DSHB)), anti-proteoglycan hyaluronic acid-binding region (12/21/1-C-6, DSHB), anti-Col1 (Abcam).

Statistical analysis

Quantitative data was expressed as mean ± standard deviation (s.d.). Statistical analyses were carried out with OriginPro 9.1 by analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Tukey's and Bonferonni's post-hoc tests for multiple comparisons and p values less than 0.05 were considered as statistically significant.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This work was funded by Swiss National Science Foundation (315230_159783 and 315230_143667), Center for Applied Biotechnology and Molecular Medicine (CABMM), FIFA/F-MARC (FIFA Medical Assessment and Research Center), The Norwegian Research Council (221576), and the National Institutes of Health (NIH R01 HD049808). The authors thankfully acknowledge Andac Armutlulu for preparation of the electron microscopy samples, Priscilla Briquez, Büsra Yagabasan and Michael Pichler for their assistance in western blotting experiments, Guglielmo Pacliccia for helping with FTIR measurements. The type II collagen (II-II6B3) antibody developed by T. F. Linsenmayer and the proteoglycan hyaluronic acid-binding region antibody (12/21/1-C-6) developed by B. Caterson were obtained from the Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank developed under the auspices of the NICHD and maintained by the University of Iowa, Department of Biology, Iowa City, IA.

Footnotes

Supporting Information

Supporting Information is available from the Wiley Online Library or from the author.

Contributor Information

Ece Öztürk, Cartilage Engineering+ Regeneration, ETH Zurich, Otto-Stern-Weg 7, 8093 Zurich, Switzerland.

Øystein Arlov, Department of Biotechnology, Norwegian University of Science and Technology, Sem Sælands vei 6/8, 7034 Trondheim, Norway.

Seda Aksel, Department of Materials, Polymer Technology Laboratory, ETH Zurich, Vladimir-Prelog-Weg 1-5/10, 8093, Zurich, Switzerland.

Dr. Ling Li, Department of Developmental Biology, Washington University School of Medicine, St. Louis, MO 63110, USA

Prof. David M. Ornitz, Department of Developmental Biology, Washington University School of Medicine, St. Louis, MO 63110, USA

Prof. Gudmund Skjåk-Bræk, Department of Biotechnology, Norwegian University of Science and Technology, Sem Sælands vei 6/8, 7034 Trondheim, Norway

Prof. Marcy Zenobi-Wong, Cartilage Engineering+ Regeneration, ETH Zurich, Otto-Stern-Weg 7, 8093 Zurich, Switzerland.

References

- 1.Hynes RO. Science. 2009;326:1216. doi: 10.1126/science.1176009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Watt FM, Huck WT. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2013;14:467. doi: 10.1038/nrm3620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Discher DE, Mooney DJ, Zandstra PW. Science. 2009;324:1673. doi: 10.1126/science.1171643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bonnans C, Chou J, Werb Z. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2014;15:786. doi: 10.1038/nrm3904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rice JJ, Martino MM, De Laporte L, Tortelli F, Briquez PS, Hubbell JA. Adv. Healthcare Mater. 2013;2:57. doi: 10.1002/adhm.201200197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Discher DE, Janmey P, Wang YL. Science. 2005;310:1139. doi: 10.1126/science.1116995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chaudhuri O, Koshy ST, Branco da Cunha C, Shin JW, Verbeke CS, Allison KH, Mooney DJ. Nat. Mater. 2014;13:970. doi: 10.1038/nmat4009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Guvendiren M, Burdick JA. Nat. Commun. 2012;3:792. doi: 10.1038/ncomms1792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wen JH, Vincent LG, Fuhrmann A, Choi YS, Hribar KC, Taylor-Weiner H, Chen S, Engler AJ. Nat. Mater. 2014;13:979. doi: 10.1038/nmat4051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Trappmann B, Gautrot JE, Connelly JT, Strange DG, Li Y, Oyen ML, Cohen Stuart MA, Boehm H, Li B, Vogel V, Spatz JP, Watt FM, Huck WT. Nat. Mater. 2012;11:642. doi: 10.1038/nmat3339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Khetan S, Guvendiren M, Legant WR, Cohen DM, Chen CS, Burdick JA. Nat. Mater. 2013;12:458. doi: 10.1038/nmat3586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McMurray RJ, Gadegaard N, Tsimbouri PM, Burgess KV, McNamara LE, Tare R, Murawski K, Kingham E, Oreffo RO, Dalby MJ. Nat. Mater. 2011;10:637. doi: 10.1038/nmat3058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Benoit DS, Schwartz MP, Durney AR, Anseth KS. Nat. Mater. 2008;7:816. doi: 10.1038/nmat2269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Webb K, Hlady V, Tresco PA. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. 1998;41:422. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4636(19980905)41:3<422::aid-jbm12>3.0.co;2-k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Varghese S, Hwang NS, Canver AC, Theprungsirikul P, Lin DW, Elisseeff J. Matrix Biol. 2008;27:12. doi: 10.1016/j.matbio.2007.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hardingham TE, Fosang AJ. FASEB J. 1992;6:861. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Knudson CB, Knudson W. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 2001;12:69. doi: 10.1006/scdb.2000.0243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hacker U, Nybakken K, Perrimon N. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2005;6:530. doi: 10.1038/nrm1681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Esko JD, Kimata K, Lindahl U. In: Essentials of Glycobiology. Varki A, Cummings RD, Esko JD, Freeze HH, Stanley P, Bertozzi CR, Hart GW, Etzler ME, editors. Cold Spring Harbor; NY: 2009. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Miller T, Goude MC, McDevitt TC, Temenoff JS. Acta Biomater. 2014;10:1705. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2013.09.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Urban JP, Maroudas A, Bayliss MT, Dillon J. Biorheology. 1979;16:447. doi: 10.3233/bir-1979-16609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lyon M, Rushton G, Gallagher JT. J. Biol. Chem. 1997;272:18000. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.29.18000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gospodarowicz D, Cheng J. J. Cell. Physiol. 1986;128:475. doi: 10.1002/jcp.1041280317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ornitz DM, Yayon A, Flanagan JG, Svahn CM, Levi E, Leder P. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1992;12:240. doi: 10.1128/mcb.12.1.240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ornitz DM. Bioessays. 2000;22:108. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-1878(200002)22:2<108::AID-BIES2>3.0.CO;2-M. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schlessinger J, Plotnikov AN, Ibrahimi OA, Eliseenkova AV, Yeh BK, Yayon A, Linhardt RJ, Mohammadi M. Mol. Cell. 2000;6:743. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)00073-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Guimond SE, Turnbull JE. Curr. Biol. 1999;9:1343. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(00)80060-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ornitz DM, Itoh N. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev.: Dev. Biol. 2015;4:215. doi: 10.1002/wdev.176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sakiyama-Elbert SE. Acta Biomater. 2014;10:1581. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2013.08.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Liang Y, Kiick KL. Acta Biomater. 2014;10:1588. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2013.07.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Liekens S, Leali D, Neyts J, Esnouf R, Rusnati M, Dell'Era P, Maudgal PC, De Clercq E, Presta M. Mol. Pharmacol. 1999;56:204. doi: 10.1124/mol.56.1.204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Miao HQ, Ornitz DM, Aingorn E, Ben-Sasson SA, Vlodavsky I. J. Clin. Invest. 1997;99:1565. doi: 10.1172/JCI119319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nguyen TH, Kim SH, Decker CG, Wong DY, Loo JA, Maynard HD. Nat. Chem. 2013;5:221. doi: 10.1038/nchem.1573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.DeLise AM, Fischer L, Tuan RS. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2000;8:309. doi: 10.1053/joca.1999.0306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ellman MB, An HS, Muddasani P, Im HJ. Gene. 2008;420:82. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2008.04.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fortier LA, Barker JU, Strauss EJ, McCarrel TM, Cole BJ. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 2011;469:2706. doi: 10.1007/s11999-011-1857-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ellsworth JL, Berry J, Bukowski T, Claus J, Feldhaus A, Holderman S, Holdren MS, Lum KD, Moore EE, Raymond F, Ren H, Shea P, Sprecher C, Storey H, Thompson DL, Waggie K, Yao L, Fernandes RJ, Eyre DR, Hughes SD. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2002;10:308. doi: 10.1053/joca.2002.0514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pap T, Korb-Pap A. Nat. Rev. Rheumatol. 2015;11:606. doi: 10.1038/nrrheum.2015.95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chia SL, Sawaji Y, Burleigh A, McLean C, Inglis J, Saklatvala J, Vincent T. Arthritis Rheum. 2009;60:2019. doi: 10.1002/art.24654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Davidson D, Blanc A, Filion D, Wang H, Plut P, Pfeffer G, Buschmann MD, Henderson JE. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:20509. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M410148200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ornitz DM, Marie PJ. Genes Dev. 2015;29:1463. doi: 10.1101/gad.266551.115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chuang CY, Lord MS, Melrose J, Rees MD, Knox SM, Freeman C, Iozzo RV, Whitelock JM. Biochemistry (Mosc) 2010;49:5524. doi: 10.1021/bi1005199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.French MM, Smith SE, Akanbi K, Sanford T, Hecht J, Farach-Carson MC, Carson DD. J. Cell Biol. 1999;145:1103. doi: 10.1083/jcb.145.5.1103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Smith SM, West LA, Govindraj P, Zhang X, Ornitz DM, Hassell JR. Matrix Biol. 2007;26:175. doi: 10.1016/j.matbio.2006.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Vincent TL, McLean CJ, Full LE, Peston D, Saklatvala J. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2007;15:752. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2007.01.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chintala SK, Miller RR, McDevitt CA. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1994;310:180. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1994.1155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hilton MJ, Gutierrez L, Martinez DA, Wells DE. Bone. 2005;36:379. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2004.09.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kluppel M, Wight TN, Chan C, Hinek A, Wrana JL. Development. 2005;132:3989. doi: 10.1242/dev.01948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Settembre C, Arteaga-Solis E, McKee MD, de Pablo R, Al Awqati Q, Ballabio A, Karsenty G. Genes Dev. 2008;22:2645. doi: 10.1101/gad.1711308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mertz EL, Facchini M, Pham AT, Gualeni B, De Leonardis F, Rossi A, Forlino A. J. Biol. Chem. 2012;287:22030. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.116467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Toh WS, Spector M, Lee EH, Cao T. Mol. Pharm. 2011;8:994. doi: 10.1021/mp100437a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ducheyne P, Mauck RL, Smith DH. Nat. Mater. 2012;11:652. doi: 10.1038/nmat3392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Holtzer H, Abbott J, Lash J, Holtzer S. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1960;46:1533. doi: 10.1073/pnas.46.12.1533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Darling EM, Athanasiou KA. J. Orthop. Res. 2005;23:425. doi: 10.1016/j.orthres.2004.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Rowley JA, Madlambayan G, Mooney DJ. Biomaterials. 1999;20:45. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(98)00107-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Arlov O, Aachmann FL, Sundan A, Espevik T, Skjak-Braek G. Biomacromolecules. 2014;15:2744. doi: 10.1021/bm500602w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Morch YA, Donati I, Strand BL, Skjak-Braek G. Biomacromolecules. 2006;7:1471. doi: 10.1021/bm060010d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Skjakbraek G, Zanetti F, Paoletti S. Carbohydr. Res. 1989;185:131. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Mhanna R, Kashyap A, Palazzolo G, Vallmajo-Martin Q, Becher J, Moller S, Schnabelrauch M, Zenobi-Wong M. Tissue Eng., Part A. 2014;20:1454. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2013.0544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Freeman I, Kedem A, Cohen S. Biomaterials. 2008;29:3260. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2008.04.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Rozenblatt-Rosen O, Mosonego-Ornan E, Sadot E, Madar-Shapiro L, Sheinin Y, Ginsberg D, Yayon A. J. Cell Sci. 2002;115:553. doi: 10.1242/jcs.115.3.553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Mandl EW, Jahr H, Koevoet JL, van Leeuwen JP, Weinans H, Verhaar JA, van Osch GJ. Matrix Biol. 2004;23:231. doi: 10.1016/j.matbio.2004.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Martin I, Vunjak-Novakovic G, Yang J, Langer R, Freed LE. Exp. Cell Res. 1999;253:681. doi: 10.1006/excr.1999.4708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Tsang M, Friesel R, Kudoh T, Dawid IB. Nat. Cell Biol. 2002;4:165. doi: 10.1038/ncb749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.He Q, Yang X, Gong Y, Kovalenko D, Canalis E, Rosen CJ, Friesel RE. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2014;29:1217. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.2114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ornitz DM, Leder P. J. Biol. Chem. 1992;267:16305. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Allen JL, Cooke ME, Alliston T. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2012;23:3731. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E12-03-0172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Krejci P. Mutat. Res., Rev. Mutat. Res. 2014;759:40. doi: 10.1016/j.mrrev.2013.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Murakami S, Kan M, McKeehan WL, de Crombrugghe B. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2000;97:1113. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.3.1113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Martino MM, Briquez PS, Guc E, Tortelli F, Kilarski WW, Metzger S, Rice JJ, Kuhn GA, Muller R, Swartz MA, Hubbell JA. Science. 2014;343:885. doi: 10.1126/science.1247663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Badylak SF, Taylor D, Uygun K. Annu. Rev. Biomed. Eng. 2011;13:27. doi: 10.1146/annurev-bioeng-071910-124743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Cukierman E, Pankov R, Stevens DR, Yamada KM. Science. 2001;294:1708. doi: 10.1126/science.1064829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Prewitz MC, Seib FP, von Bonin M, Friedrichs J, Stissel A, Niehage C, Muller K, Anastassiadis K, Waskow C, Hoflack B, Bornhauser M, Werner C. Nat. Methods. 2013;10:788. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Flaim CJ, Chien S, Bhatia SN. Nat. Methods. 2005;2:119. doi: 10.1038/nmeth736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.