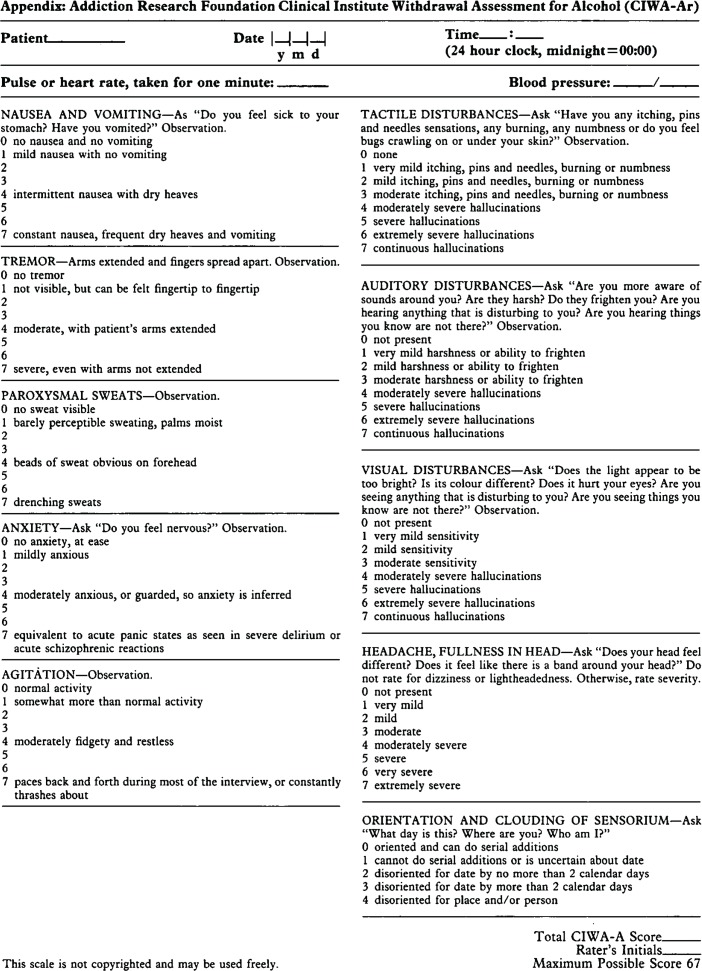

The Clinical Institute Withdrawal Assessment for Alcohol–Revised (CIWA-Ar) protocol (Figure 1)1 is the most common method of treating alcohol withdrawal in our institution and it is frequently used by family physicians. Although various rating scales for alcohol withdrawal have been described, the CIWA-Ar protocol managing withdrawal with benzodiazepines is well established.2–4 Symptom-triggered benzodiazepine dosing has been demonstrated to lead to shorter duration of treatment and lower medication use compared with fixed-schedule dosing.5 Although the CIWA-Ar protocol was validated in medically cleared patients in an alcohol detoxification setting, it has also been evaluated in hospital settings.1,6–8 However, the application of the CIWA-Ar needs to be carefully considered, and inappropriate use of the protocol has been documented.3 This article describes a case in which an objective alcohol withdrawal scale (OAWS) was more useful for treatment, as the CIWA-Ar could not be applied.

Figure 1.

The Clinical Institute Withdrawal Assessment for Alcohol–Revised scale

Reproduced from Sullivan et al.1

Case

A 57-year-old Polish man presented to an urban hospital at 12:18 pm after falling while intoxicated. His Glasgow Coma Scale score was 11 and his serum ethanol level was 75 mmol/L at 3:53 pm. An eyebrow laceration was sutured, and a computed tomography scan of his head showed a trace subarachnoid hemorrhage. After review by the neurosurgery department, the patient was kept for observation and began to exhibit signs of alcohol withdrawal. A CIWA-Ar protocol using lorazepam was initiated at 8:50 pm with an initial score of 13. Upon reassessment at 7:41 am, the patient had received a total of 10 mg of oral lorazepam and a consultation with the internal medicine department was initiated. The patient’s withdrawal continued to worsen, and lorazepam was switched to diazepam. When seen in the internal medicine department at 3:45 pm, a regular 10-mg dose of oral diazepam 3 times a day was added, and a consultation with the Addiction Medicine Consult Team (AMCT) was requested.

The patient was seen by the AMCT at 6:00 pm, 30 hours into the withdrawal process and 21 hours since starting the CIWA-Ar protocol. The patient had received a total of 18 mg of oral lorazepam, 40 mg of intravenous diazepam, and 20 mg of oral diazepam, and he continued to exhibit signs of severe alcohol withdrawal including agitation, diaphoresis, hypertension, tachycardia, and tremor. He was unable to converse in English, although he was able to speak Polish when a telephone translation service was briefly available. He was confused and disoriented to time and place. There was minimal collateral history, with no previous admissions, no pharmacy records, no next of kin available, and a retired family physician on record. He had signs of chronic liver disease including clubbing, palmar erythema, and a palpable liver. Given the patient’s inability to converse, the AMCT discontinued the CIWA-Ar protocol and constructed an OAWS (Box 1). Because of the apparent liver disease, diazepam was changed to 1 mg of oral lorazepam (which does not require hepatic oxidation) 4 times a day, with lorazepam as needed based on the OAWS.

The patient’s withdrawal improved and his lorazepam requirements gradually declined. On day 4, scheduled lorazepam was decreased to 3 times a day, then to twice a day on day 5. The patient remained hypertensive and received sporadic as-needed doses because of this. On day 6, the OAWS and treatment with lorazepam was discontinued and the patient was discharged in stable condition on day 8. Recommendations were provided to the patient’s Polish-speaking family physician regarding relapse prevention medications, with acamprosate being the drug of choice given his liver dysfunction.

Box 1. Objective alcohol withdrawal scale.

The objective alcohol withdrawal scale is applied as follows:

- Score 1 point for each of

- -systolic blood pressure ≥ 160 mm Hg or diastolic blood pressure ≥ 90 mm Hg;

- -heart rate ≥ 90 beats/min;

- -tremor;

- -diaphoresis; and

- -agitation

If total ≥ 2 give 1 mg oral lorazepam (or 10 mg of diazepam)

If total ≥ 3 give 2 mg oral lorazepam (or 20 mg of diazepam)

Reassess every hour until score is < 2 for 3 consecutive measures, then reassess every 6 hours for 24 hours, then every 24 hours for 72 hours, then discontinue

Discussion

An important limitation of the CIWA-Ar is its heavily subjective nature. Only 3 of 10 components (tremor, paroxysmal sweats, agitation) can be rated by observation alone. The other 7 components require at least some discussion with the patient. Given that benzodiazepines are provided based on the CIWA-Ar score, there is risk of incorrect dosing when scores are unreliable, which harbours potential for patient harm. There are 2 primary reasons why the CIWA-Ar was unreliable in this case. First, there was a substantial language barrier preventing the discussions necessary for accurate scoring. This became clearer as the patient’s withdrawal improved and he was still unable to answer simple questions in English. Even with an interpreter available, CIWA-Ar might remain impractical, as it requires frequent reassessments and would necessitate 24-hour interpreter coverage. The second limitation of the CIWA-Ar was subtler; the patient was confused and disoriented, so even in the absence of a communication barrier, his responses might have been unreliable. In a hospitalized population this might be a common scenario; acute medical issues can contribute to delirium and complicate the clinical picture.

While this case illustrates 2 reasons to use an OAWS, other common reasons exist. These might include patients with a clouded sensorium from acute psychosis or severe dementia, those with mechanical communication problems including severe facial trauma limiting speech and vision, and those with intubation.

Alternative assessment tools and clinical pathways have been proposed for inpatient management of alcohol withdrawal, but like the CIWA-Ar, they often require a reliable history.9,10 The approach presented here has proved reliable for treatment of complex alcohol withdrawal by a busy AMCT in a tertiary Canadian hospital. The OAWS in Box 1 is not intended as an alternative to the CIWA-Ar and therefore has not been validated as such. Rather, it is an approach to treatment that can be useful when other validated tools cannot be reliably applied. It is based on objective findings and can be modified to fit the clinical situation. For example, in a patient with poorly controlled hypertension, blood pressure could be excluded or a higher blood pressure cutoff chosen. Similarly, heart rate might be excluded for a patient with uncontrolled atrial fibrillation or sepsis, and tremor excluded for a patient with essential tremor or parkinsonism. Additionally, the OAWS can be modified by changing the cutoff for scores prompting doses of benzodiazepines. In this case, the patient was unwell and required high doses, so we opted for a liberal scale to minimize underdosing. In more moderate withdrawal or where there was concern for benzodiazepine toxicity, cutoffs of 3 or more, or 4 or more, would be more benzodiazepine sparing.

Conclusion

The OAWS can be useful for cases of alcohol withdrawal in which the CIWA-Ar is unreliable. The OAWS can be used as a framework and tailored to individual cases with consideration of comorbidities and withdrawal severity.

EDITOR’S KEY POINTS

Because accurate application of the Clinical Institute Withdrawal Assessment for Alcohol–Revised requires taking a detailed medical history, it should not be used when a substantial language barrier exists, or when patients cannot provide a reliable history because of delirium, dementia, psychosis, etc.

An objective alcohol withdrawal scale can be tailored to comorbidities and severity of withdrawal, but it has not been validated as an alternative to the Clinical Institute Withdrawal Assessment for Alcohol–Revised protocol. It is intended as an approach to treatment that can be useful when validated protocols cannot reliably be applied.

POINTS DE REPÈRE DU RÉDACTEUR

Étant donné que l’application exacte de l’échelle des symptômes de sevrage de l’alcool (Clinical Institute Withdrawal Assessment for Alcohol–Revised ou CIWA-AR) exige une anamnèse détaillée, cette échelle ne devrait pas être utilisée s’il existe des barrières de langue importantes ou lorsque les patients ne peuvent pas expliquer leurs antécédents médicaux de manière fiable à cause d’un delirium, d’une démence, d’une psychose et ainsi de suite.

Une échelle objective des symptômes de sevrage de l’alcool peut être adaptée aux comorbidités et à la gravité des symptômes, mais elle n’a pas été validée comme solution de rechange au protocole CIWA-AR. Elle a pour but de servir d’approche thérapeutique susceptible d’être utile lorsque les protocoles validés ne peuvent pas être appliqués de manière fiable.

Footnotes

This article has been peer reviewed.

Cet article a fait l’objet d’une révision par des pairs.

Competing interests

None declared

References

- 1.Sullivan JT, Sykora K, Schneiderman J, Naranjo CA, Sellers EM. Assessment of alcohol withdrawal: the revised Clinical Institute Withdrawal Assessment for Alcohol scale (CIWA-Ar) Br J Addict. 1989;84(11):1353–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1989.tb00737.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bayard M, McIntyre J, Hill KR, Woodside J., Jr Alcohol withdrawal syndrome. Am Fam Physician. 2004;69(6):1443–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hecksel KA, Bostwick JM, Jaeger TM, Cha SS. Inappropriate use of symptom-triggered therapy for alcohol withdrawal in the general hospital. Mayo Clin Proc. 2008;83(3):274–9. doi: 10.4065/83.3.274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Williams D, Lewis J, McBride A. A comparison of rating scales for the alcohol-withdrawal syndrome. Alcohol Alcohol. 2001;36(2):104–8. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/36.2.104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Daeppen JB, Gache P, Landry U, Sekera E, Schweizer V, Gloor S, et al. Symptom-triggered vs fixed-schedule doses of benzodiazepine for alcohol withdrawal: a randomized treatment trial. Arch Intern Med. 2002;162(10):1117–21. doi: 10.1001/archinte.162.10.1117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Reoux JP, Miller K. Routine hospital alcohol detoxification practice compared to symptom triggered management with an objective withdrawal scale (CIWA-Ar) Am J Addict. 2000;9(2):135–44. doi: 10.1080/10550490050173208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jaeger TM, Lohr RH, Pankratz VS. Symptom-triggered therapy for alcohol withdrawal syndrome in medical inpatients. Mayo Clin Proc. 2001;76(7):695–701. doi: 10.4065/76.7.695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sullivan JT, Swift RM, Lewis DC. Benzodiazepine requirements during alcohol withdrawal syndrome: clinical implications of using a standardized withdrawal scale. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 1991;11(5):291–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McPherson A, Benson G, Forrest EH. Appraisal of the Glasgow assessment and management of alcohol guideline: a comprehensive alcohol management protocol for use in general hospitals. QJM. 2012;105(7):649–56. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/hcs020. Epub 2012 Feb 10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Repper-DeLisi J, Stern TA, Mitchell M, Lussier-Cushing M, Lakatos B, Fricchione GL, et al. Successful implementation of an alcohol-withdrawal pathway in a general hospital. Psychosomatics. 2008;49(4):292–9. doi: 10.1176/appi.psy.49.4.292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]