Abstract

Objective

Abstracts of scientific reports are sometimes criticized for exaggerating significant results when compared to the corresponding full texts. Such abstracts can mislead the readers. We aimed to conduct a systematic review of overstatements in abstract conclusions in psychiatry trials.

Methods

We searched for randomized controlled trials published in 2014 that explicitly claimed effectiveness of any intervention for mental disorders in their abstract conclusion, using the Cochrane Register of Controlled Trials. Claims of effectiveness in abstract conclusion were categorized into three types: superiority (stating superiority of intervention to control), limited superiority (intervention has limited superiority), and equal efficactiveness (claiming equal effectiveness of intervention with standard treatment control), and full text results into three types: significant (all primary outcomes were statistically significant in favor of the intervention), mixed (primary outcomes included both significant and non-significant results), or all results non-significant. By comparing these classifications, we assessed whether each abstract was overstated. Our primary outcome was the proportion of overstated abstract conclusions.

Results

We identified and included 60 relevant trials. 20 out of 60 studies (33.3%) showed overstatements. Nine reports reported only significant results although none of their primary outcomes were significant. Large sample size (>300) and publication in high impact factor (IF>10) journals were associated with low occurrence of overstatements.

Conclusions

We found that one in three psychiatry studies claiming effectiveness in their abstract conclusion, either superior to control or equal to standard treatment, for any mental disorders were overstated in comparison with the full text results. Readers of the psychiatry literature are advised to scrutinize the full text results regardless of the claims in the abstract.

Trial registration

University hospital Medical Information Network (UMIN) Clinical Trials Registry (UMIN000018668)

Introduction

Abstracts of scientific articles deliver the most essential findings from the research. In fact, they are the primary source of information for many readers because of their accessibility and conciseness [1, 2]. In particular, conclusion sections of abstracts convey key messages of the research. Consequently, eye-catching abstracts attract many readers, and authors are often under pressure to produce abstracts with interesting, positive findings [3].

However, there is mounting criticism that some abstract conclusions of scientific articles present the results of a randomized controlled trial (RCT) too strongly in favor of the investigation of interest. That is, some abstracts emphasize beneficial effects of intervention beyond the actual findings mentioned in the corresponding full texts. Such distortion can have detrimental impacts, for readers may read abstracts only and take abstract conclusions at face value. Even if readers read entire articles, their interpretation of the articles may be anchored by the exaggerated reporting of abstract conclusions.

Despite the recent efforts to promote transparent reporting, studies have found that many of the abstracts fall short of a standard specifically stated in the new CONSORT guideline [4]. The first review of this problem was provided by Boutron et al [5]. They evaluated each of 72 randomized controlled trials (RCTs) with non-significant primary outcomes through their consensus judgment based on the following definition of ‘spin’: (i) a focus on statistically significant results, (ii) interpreting non-significant results as showing treatment equivalence or comparable effectiveness, and (iii) claiming or emphasizing the beneficial effect of treatment despite non-significant results. According to the study, about 60% of the cases were classified as having spins and spins were most commonly found in abstract conclusions. Subsequently, several studies examined spins in trial reports from various subspecialties [6–8] or in observational studies [9] and even in press prelease by academia [10, 11]. A focus on positive findings was also found in biological studies, leading to more citation of positive results or spun negative studies [12, 13]. Consequently, together with the citation bias, these exaggerations can mislead the press, clinicians and researchers, and poses an obstacle to future research [12–14].

While these studies shed some light on the prevalence of distorted reporting in abstracts, they, however, have limitations. First of all, spin as defined by these investigators may not be free from the subjective and arbitrary viewpoint of investigators and potentially leave room for debate [15]. We need a more objective and systematic approach for a proper assessment of the magnitude of this problem. Second, each of previous studies was limited to specific subspecialties such as rheumatology [7], wound research [16], surgery [8] or to limited topics such as early psychosis trials [6]. As far as we know, there has been no study that evaluated overstatements in psychiatry trial to inform the readers what proportion of abstract conclusions they read may be exaggerated.

This study aimed to evaluate the prevalence and patterns of overstated abstract conclusions in trials claiming effectiveness of interventions, either superior to control or equal to standard treatment for any mental disorders, by systematically and separately evaluating their abstract conclusions and the results of corresponding full text. In addition, we examined the predictors of overstatements.

Materials and methods

The details of the method can be found in the published protocol [17]. Neither methods or outcomes have been changed critically from our protocol. The only amendment was that we added multivariable logistic regression about factors that had significant association with overstatement. Since we used secondary data from published trial reports, this trial require no ethical approval. This protocol was registered in the University hospital Medical Information Network (UMIN) Clinical Trials Registry (UMIN000018668).

Study selection

We (KS, AMS) searched Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) to identify all RCTs claiming effectiveness of intervention for mental disorders published in the English language in 2014 (search data: August 2015) We used the MeSH term ‘mental disorders’ Mesh-term sub-headings ‘drug therapy’ and ‘therapy’, and publication type ‘randomised controlled trial’ (S1 Table).

The selection covered any kinds of interventions, from common pharmacological intervention to non-drug therapy such as aromatherapy and exercise. We included published reports whose abstract conclusions claimed superior or equal effectiveness of intervention to control. ‘Equal effectiveness’ meant that they declared the intervention was equally effective as the standard treatment for the targeted mental illness in their abstract conclusions. We focused on the primary (if stated) or all outcomes (if none was declared primary) in the abstract conclusions. We excluded those reports that explicitly declared the intervention has not superior to the control or effective as standard treatment on their primary outcomes in the abstract conclusion (e.g. ‘the treatment has no significant effect on the primary outcome, depression’), because it is highly unlikely general readers considers those abstract conclusions as claiming effectiveness. We excluded unstructured studies because it would be impossible to determine the conclusion section of them. Trials with more than two arms were also excluded because they would lead to multiple evaluations between different arms. Secondary analysis studies, feasibility studies, and cost effectiveness studies were not included either because their aims do not lie in the evaluation of treatment effectiveness.

Data extraction

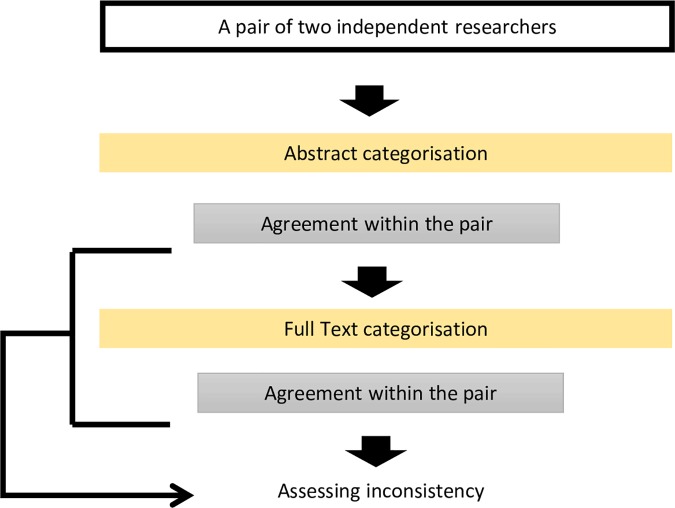

Two independent researchers identified the eligible studies. Any disagreement was resolved through discussion and in consultation with a third member of the research team. A pair of researchers, who have not screened and therefore have not read the abstract and the paper, independently collected information from each study in the following three steps: categorization of abstracts, classification of primary outcomes, and assessing inconsistency between the two. The agreement within each pair was reported at each step of assessments (Fig 1).

Fig 1. Flow chart of assessment of selected studies.

This was to maintain the independence of appraisal from any influence of full text on abstract and vice versa.

We extracted the relevant data from each study using the Excel spreadsheet specially made for this study. The data included: the type of intervention, targeted mental illness, the region where the study was conducted, the number of randomized patients, study design, primary outcomes supposed in abstract conclusion, the results of actual primary and secondary outcomes in the full text. Data extraction, categorization of abstracts, and the evaluation of the primary outcomes were done independently by the two teams consisting of two or three assessors. Any disagreements in the team were resolved by the discussions with a third member of the team (TAF). Citation was recorded in each study PDF document and kept as a reference.

Classification of abstract conclusions

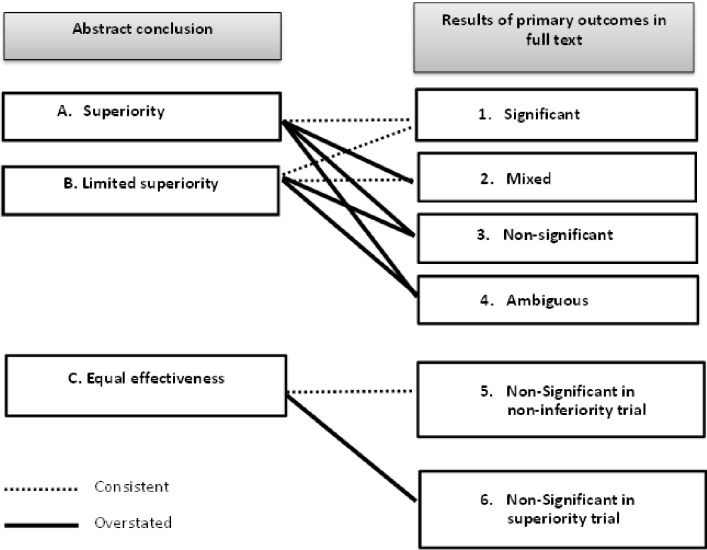

First, we (KS, YH, NT, HI, AMS) categorized each abstract conclusion into one of the three types according to the level of effectiveness it claimed without reading their full text (Fig 2). When a trial only stated significant effectiveness of intervention in its abstract conclusion, it was classified as ‘superiority’. On the other hand, a trial reporting both significant and non-significant findings with respect to intervention’s effectiveness was considered as ‘limited superiority’ (e.g. ‘treatment significantly improved quality of life than the control, but not depression’, ‘treatment enhanced the rates of recovery, with the effect limited to patients with severe depression’, or ‘treatment improved quality of life and anxiety, and had limited effect on depression’). Trials claiming equal effectiveness of the intervention to the standard treatment (e.g. ‘intervention A was equally effective as standard treatment B’) were categorized as ‘equal effectiveness’. Note that our judgment was based solely on the abstract conclusion, regardless of the primary outcome results discussed in the results section of abstract or full text.

Fig 2. Definitions of overstatement in abstract conclusion.

Classification of results of primary outcome in the full text

Secondly, we (KS, YH, NT, HI, AMS) assessed the level of statistical evidence for their findings in primary outcome(s) in full text, and categorized them into one of the three: significant (all primary outcomes were statistically significant), mixed (primary outcome included statistically significant and non-significant results), and all non-significant. Note that no results of any secondary analysis or subgroup analysis results were taken into consideration when determining the category.

We defined those trials as having ‘ambiguous primary outcome’ if they did not explicitly state any outcome(s) as ‘primary’ or ‘main analysis’, except when they only measured a single outcome. In such cases, the single outcome was considered as primary. When a trial did not specify the primary time point, end of treatment was regarded as primary in trials studying the effectiveness of the acute treatment. We also examined if a trial was designed as superiority or non-inferiority trial.

Furthermore, we defined a trial lacking vital information as ‘sub-quality trial’, such as lacking statistical analysis of the main comparison, and having no assessment at the end of the treatment.

Assessing inconsistency between abstract and results in full text

Using our approach, overstated abstracts were deduced systematically by comparing the classification of the abstract conclusion and that of the full text for each study as shown in Fig 2. Naturally, a trial with abstract conclusion categorized as ‘superiority’ should have statistically significant results in all of their declared primary outcomes. Similarly, a ‘limited superiority’ abstract conclusion should correspond to mixed results (they should have significant results in at least one primary outcome). ‘Equal effectiveness’ abstract conclusion category must only be supported by the full text describing non-inferiority trials showing effectiveness of treatment at least as much as the control or worse only by a pre-specified amount. Note that by definition, non-inferiority trials are designed and conducted using a specific methodology under a specific design, such as the sample size calculation and equivalence margin pre-specification. The full text results should show that the upper limit of 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for the difference between intervention and control lies below that equivalence margin [18]. For a study that did not fall into any of the above patterns, it is regarded as having an overstated abstract conclusion.

Outcomes of the current study

Primary outcome

Our primary outcome was the proportion of overstated abstract conclusions out of all the studies that had claimed effectiveness in their abstract conclusions. Fig 2 shows correspondences between abstract conclusions and results of primary outcomes in full text. Our primary outcome is then the sum of studies in the categories A-2, A-3, A-4, B-3, B-4 and C-6, divided by all the included studies.

Secondary outcome

We next examined which of the abstracts, stating ‘superiority’ (category A in Fig 2) or stating ‘limited superiority’ (category B), are more likely to be overstating the primary outcomes in their full texts. This was examined by calculating the risk ratio (RR) of the proportion of explicit overstatement among the ‘superiority’ category (A-2 + A-3 over A) over that among the ‘limited superiority’ category (B-3 over B).

Sub-group analyses

We investigated factors that can potentially be associated with inconsistencies, such as impact factors (IF) of the journal in which the trials are published, source(s) of funding, and the sample size. For our purposes, top ten impact factor journals as ranked in Journal Citation Report (2014) in general medicine, psychiatry, and psychology were regarded as high IF journals. The differences between the groups were checked by Fisher’s exact test for dichotomous data, and Mann-Whitney U- test for continuous data. We used SPSS statistics 22 (SPSS Japan Inc., Tokyo, Japan) and considered p<0.05 (two-sided) as significant. If any factor had significant association with overstatement, we calculated the odds ratio by using logistic regression analysis. We excluded sub-quality trials when conducting this sub-group analysis because we could not tell whether they overstated the result or not.

Results

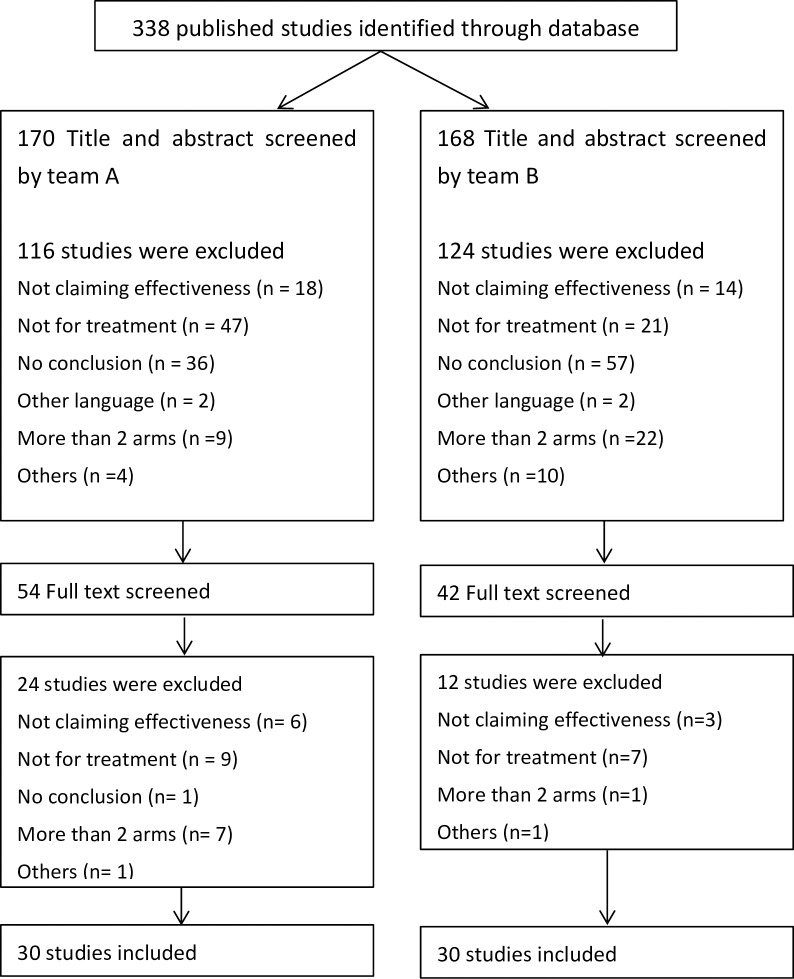

Through our electronic search in the Cochrane CENTRAL, we identified 338 published studies, and 60 studies were included in total after screening by two pairs of investigators (See S2 for the list of all included trials). 93 studies were excluded due to the lack of a conclusion section in their abstracts (Fig 3). Table 1 shows the characteristics of the included studies. The sample size ranged widely (mean: 199, median 131, range 21 to 1310).

Fig 3. Flow chart of study selection.

Table 1. Characteristics of trials (n = 60).

| Characteristics | Total number of Trials titirald |

% | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Journal | High IF journals | 26 | 43.3 |

| Other IF journals | 34 | 56.7 | |

| Region | North America | 37 | 61.7 |

| Europe | 14 | 23.3 | |

| Cross-continental | 2 | 3.3 | |

| Africa | 2 | 3.3 | |

| Asia | 2 | 3.3 | |

| Oceania | 1 | 1.7 | |

| Interventions |

Non-drug therapy | 36 | 60.0 |

| Drug therapy | 16 | 26.7 | |

| Combination | 8 | 13.3 | |

| Sponsorship by for-profit entity |

No | 48 | 80.0 |

| Yes | 9 | 15.0 | |

| Unclear | 3 | 5.0 | |

| Design | Superiority | 58 | 96.7 |

| Non-inferiority | 2 | 3.3 | |

| Included disorders | Problems related to substance use disorders |

19 |

31.7 |

| Mood disorders | 11 | 18.3 | |

| Cognitive disorders | 4 | 6.7 | |

| Schizophrenia | 2 | 3.3 | |

| Others | 24 | 40.0 |

Categorization of abstracts and full text

In the abstract conclusion, 44 (73.3%) studies claimed superior effectiveness of interventions compared to control, 13 (21.7%) studies stated limited effectiveness, and three (5.0%) studies claimed equal effectiveness. On the other hand, in the full text, only 30 (50.0%) studies showed statistically significant difference in all primary outcomes, 13 (21.7%) studies had mixed results (significant and non-significant), and nine (15.0%) studies, all primary outcomes were non-significant. Three (5%) studies did not declare their primary outcomes in the full text (Table 2). Our inter-rater reliability was a kappa of 0.62 (95% CI: 0.40 to 0.85) for classification of abstract conclusion, and a kappa of 0.83 (95% CI: 0.71 to 0.94) for classification of full text results.

Table 2. Summary of results: Overstatements (shaded cells) in abstract conclusion (N = 60(%)).

| Full text results (rows) Abstract conclusion (columns) |

Statistically Significant | Mixed | Non-significant | Ambiguous | Sub-quality | Non-inferiority | Superiority | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Superiority | 29 | 7 | 4 | 3 | 1 | - | - | 44 |

| (48.0) | (11.7) | (6.7) | (5.0) | (1.7) | ||||

| Limited superiority | 1 | 6 | 5 | 0 | 1 | - | - | 13 |

| (1.7) | (10.0) | (8.3) | (0.0) | (1.7) | ||||

| Equal effectiveness | - | - | - | - | - | 2 | 1 | 3 |

| (3.3) | (1.7) | |||||||

| 60 | ||||||||

Comparing these abstract conclusions and the results of the primary outcomes, 20 (33.3%) studies overstated their results in the abstract, while 38 (63.3%) did not. Two studies were classified as ‘sub-quality’ because they only reported the results of subgroup analysis. Ten studies claimed superiority or limited superiority of intervention even though all of their primary outcomes were statistically non-significant. (S2 Table provides details of overstatements). There was not a significant difference in our secondary outcomes, the proportion of explicit overstatement, among ‘superiority’ studies (11 out of 44) and ‘limited superiority’ studies (5 out of 13) (RR; 0.82, 95% CI, 0.35–1.93). The strategy of overstatement varied. For example, some trials with no significant primary outcomes failed to refer to non-significant results and claimed effectiveness by focusing on significant results from subgroup analyses or secondary outcomes [19, 20]. Some studies acknowledged that the outcomes were non-significant [21–23] or suggested that ‘replication is needed’ [24]; nevertheless, they still emphasized significant secondary outcomes or used phrases such as ‘… is promising treatment’ to overstate the results.

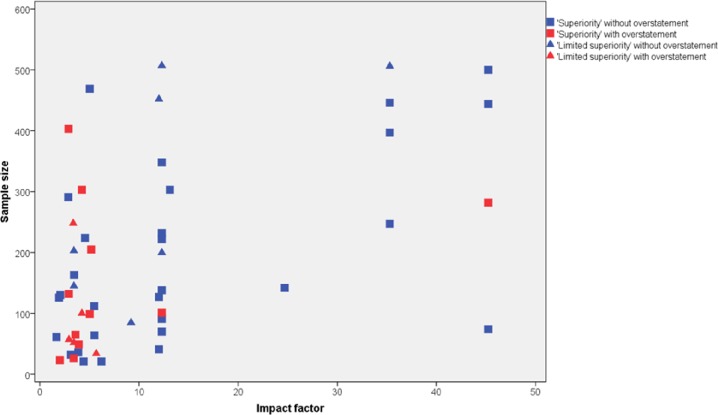

Study characteristics associated with overstatement

Sample size and impact factor of journals were significantly associated with the prevalence of overstatement (Fig 4). Studies with smaller sample size overstated more than those with larger sample size (by Mann-Whitney U- test, p = 0.049). Overstatements were less common in studies published in high impact factor journals than otherwise (the risk ratio was 0.15, 95% CI: 0.04 to 0.57). There were no significant association between sponsorship and overstated abstracts. In the multivariable logistic regression, entering associated factors together (sample size and high IF), the odds ratio of larger sample size for overstatement was 0.86 per 100 persons (95% CI: 0.53 to 1.39), and that of high IF journals was 0.09 (95% CI: 0.02 to 0.47) vs low IF journals.

Fig 4. Relation between sample size, impact factor of journal, and overstatements in ‘superiority’ and ‘limited superiority’ trials.

Discussion

The systematic comparison between the claims in the abstract conclusions and the findings of the primary outcomes in the full text revealed that 32% (14/44) of the claims for clear effectiveness of interventions for mental disorders were overstated in the abstract. Including abstracts claiming limited effectiveness or equal effectiveness, 33% (20/60) were judged to be cases of overstatement. Five studies were judged to represent sub-quality or ambiguous reportings.

By and large these figures are comparable to those reported for other subspecialties [6–8]. In other words, psychiatry fared neither better nor worse than other medical fields such as rheumatology, surgery or wound medicine. In line with a previous study which found that high impact factor and small sample size were associated with better conduct and reporting of psychiatry trials [25], our results showed that small sample size and low impact factors of journals may be suggestive of the existence of overstatements. Journals with IF less than 10 and/or trials with less than 300 participants were particularly likely to overstate the findings (Fig 4).

We faced some challenges while conducting this study that may speak for further weaknesses of the literature beyond the overstatements that we studied. For instance, we found non-structured abstracts were common in psychiatry trial reports (93/338, 28%). This is because some journals still have not introduced structured abstracts as recommended by the CONSORT statement that requires structured abstracts when reporting RCTs [26]. In addition, some of the studies reported the conclusion in ambiguous language, such as a treatment ‘may be effective [19, 27]’, or has ‘the potential [28]’. Such expressions may leave impressions that are not only different from the study’s actual findings, but also highly variable among the readers.

Strengths and limitations

The strong points of this study may be as follows. First, this study is the first systematic analysis of overstatements in the psychiatry trial literature. We have revealed that distorted abstract reporting is a fairly common practice even in psychiatry. Second, our approach is more structured than in the previous studies. In our framework, overstatements are identified through systematic evaluations of abstracts and full texts separately, and not by any overall, subjective decision call by investigators who are actively gleaning spins. Third, we adopted the viewpoint of general consumers as they would first read abstracts, and were able to provide some practical tips in navigating though the psychiatry literature.

This study also has several limitations. Although we minimized investigators presumption and prejudice in evaluation, there still was some room left for judgment for the categorization of abstract conclusions and full text results. Still, we were able to achieve high inter-rater reliability in these judgments when we followed our pre-specified protocol nonetheless. Second, this approach has not been tested outside of mental disorders, and may require some modification when it is applied to other fields. Lastly, the present study did not address the question of how much impact the overstatements actually have on the readers’ interpretation of study results. We are currently investigating this issue in a randomized controlled trial.

Implication for researchers

Despite the new guidelines [4, 29], distorted abstract reporting is regrettably a common practice, and researchers should take into consideration the impact of abstract reporting, and communicate their findings of the primary outcome in a plain direct style.

Implication for journal editors and peer reviewers

Journal editors should require that authors abide by the CONSORT guideline by providing specific writing instructions. Furthermore, journal editors and reviewers should ensure that abstracts of a paper are not overstated.

Implication for consumers of the medical literature

One third of published psychiatry articles claiming effectiveness of interventions, either superior to the control or equal to the standard treatment had overstatement in abstract conclusions. While sample size and impact factors may suggest some indication, there still is good probability of overstatements even in plausibly good articles. Because abstract conclusions in themselves reveal very little about the possible existence of overstatements, consumers of scientific literature should read articles while always being mindful of specified primary and secondary outcomes in the full text.

Supporting information

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

Data Availability

All relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files.

Funding Statement

This study was supported in part by JSPS KAKENHI (Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research) Grant Number 26670314 to TAF. The funder had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript. There was no additional internal or external funding received for this study.

References

- 1.Burke DT, Judelson AL, Schneider JC, DeVito MC, Latta D. Reading habits of practicing physiatrists. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2002;81(10):779–87. Epub 2002/10/04. doi: 10.1097/01.PHM.0000027420.36815.3F . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kurata K, Morioka T, Yokoi K, Matsubayashi M. Remarkable growth of open access in the biomedical field: analysis of PubMed articles from 2006 to 2010. PLoS One. 2013;8(5):e60925 Epub 2013/05/10. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0060925 ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC3641021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vinkers CH, Tijdink JK, Otte WM. Use of positive and negative words in scientific PubMed abstracts between 1974 and 2014: retrospective analysis. BMJ. 2015;351:h6467 Epub 2015/12/17. doi: 10.1136/bmj.h6467 ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC4677695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hopewell S, Clarke M, Moher D, Wager E, Middleton P, Altman DG, et al. CONSORT for reporting randomized controlled trials in journal and conference abstracts: explanation and elaboration. PLoS Med. 2008;5(1):e20 Epub 2008/01/25. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0050020 ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC2211558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Boutron I, Dutton S, Ravaud P, Altman DG. Reporting and interpretation of randomized controlled trials with statistically nonsignificant results for primary outcomes. JAMA. 2010;303(20):2058–64. Epub 2010/05/27. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.651 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Amos AJ. A review of spin and bias use in the early intervention in psychosis literature. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord. 2014;16(1). Epub 2014/06/19. doi: 10.4088/PCC.13r01586 ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC4048144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mathieu S, Giraudeau B, Soubrier M, Ravaud P. Misleading abstract conclusions in randomized controlled trials in rheumatology: comparison of the abstract conclusions and the results section. Joint Bone Spine. 2012;79(3):262–7. Epub 2011/07/08. doi: 10.1016/j.jbspin.2011.05.008 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Arunachalam L, Hunter IA, Killeen S. Reporting of Randomized Controlled Trials With Statistically Nonsignificant Primary Outcomes Published in High-Impact Surgical Journals. Ann Surg. 2016. Epub 2016/06/04. doi: 10.1097/sla.0000000000001795 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lazarus C, Haneef R, Ravaud P, Boutron I. Classification and prevalence of spin in abstracts of non-randomized studies evaluating an intervention. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2015;15:85 Epub 2015/10/16. doi: 10.1186/s12874-015-0079-x ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC4604617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sumner P, Vivian-Griffiths S, Boivin J, Williams A, Bott L, Adams R, et al. Exaggerations and Caveats in Press Releases and Health-Related Science News. PLoS One. 2016;11(12):e0168217 Epub 2016/12/16. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0168217 ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC5158314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sumner P, Vivian-Griffiths S, Boivin J, Williams A, Venetis CA, Davies A, et al. The association between exaggeration in health related science news and academic press releases: retrospective observational study. BMJ. 2014;349:g7015 Epub 2014/12/17. doi: 10.1136/bmj.g7015 ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC4262123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.de Vries YA, Roest AM, Franzen M, Munafo MR, Bastiaansen JA. Citation bias and selective focus on positive findings in the literature on the serotonin transporter gene (5-HTTLPR), life stress and depression. Psychol Med. 2016;46(14):2971–9. Epub 2016/08/16. doi: 10.1017/S0033291716000805 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bastiaansen JA, de Vries YA, Munafo MR. Citation Distortions in the Literature on the Serotonin-Transporter-Linked Polymorphic Region and Amygdala Activation. Biol Psychiatry. 2015;78(8):e35–6. Epub 2015/04/14. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2014.12.007 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Park IU, Peacey MW, Munafo MR. Modelling the effects of subjective and objective decision making in scientific peer review. Nature. 2014;506(7486):93–6. Epub 2013/12/07. doi: 10.1038/nature12786 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hoyles RK, Ellis RW, Wellsbury J, Lees B, Newlands P, Goh NS, et al. A multicenter, prospective, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of corticosteroids and intravenous cyclophosphamide followed by oral azathioprine for the treatment of pulmonary fibrosis in scleroderma. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;54(12):3962–70. Epub 2006/11/30. doi: 10.1002/art.22204 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lockyer S, Hodgson R, Dumville JC, Cullum N. "Spin" in wound care research: the reporting and interpretation of randomized controlled trials with statistically non-significant primary outcome results or unspecified primary outcomes. Trials. 2013;14:371 Epub 2013/11/08. doi: 10.1186/1745-6215-14-371 ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC3832286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Suganuma AM, Shinohara K, Imai H, Takeshima N, Hayasaka Y, Furukawa TA. Overstatements in abstract conclusions claiming effectiveness of interventions in psychiatry: a study protocol for a meta-epidemiological investigation. BMJ open. 2016;6(4):e009832 doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-009832 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Piaggio G, Elbourne DR, Altman DG, Pocock SJ, Evans SJ. Reporting of noninferiority and equivalence randomized trials: an extension of the CONSORT statement. JAMA. 2006;295(10):1152–60. Epub 2006/03/09. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.10.1152 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wade SL, Stancin T, Kirkwood M, Brown TM, McMullen KM, Taylor HG. Counselor-assisted problem solving (CAPS) improves behavioral outcomes in older adolescents with complicated mild to severe TBI. The Journal of head trauma rehabilitation. 2014;29(3):198–207. doi: 10.1097/HTR.0b013e31828f9fe8. CN-00993584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Melville JL, Reed SD, Russo J, Croicu CA, Ludman E, LaRocco-Cockburn A, et al. Improving care for depression in obstetrics and gynecology: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;123(6):1237–46. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000000231. CN-00992790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Beglinger LJ, Adams WH, Langbehn D, Fiedorowicz JG, Jorge R, Biglan K, et al. Results of the citalopram to enhance cognition in Huntington disease trial. Mov Disord. 2014;29(3):401–5. doi: 10.1002/mds.25750. CN-00981160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sternfeld B, Guthrie KA, Ensrud KE, LaCroix AZ, Larson JC, Dunn AL, et al. Efficacy of exercise for menopausal symptoms: a randomized controlled trial. Menopause. 2014;21(4):330–8. doi: 10.1097/GME.0b013e31829e4089. CN-00984554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Freund-Levi Y, Jedenius E, Tysen-Bäckström AC, Lärksäter M, Wahlund LO, Eriksdotter M. Galantamine versus risperidone treatment of neuropsychiatric symptoms in patients with probable dementia: an open randomized trial. The American journal of geriatric psychiatry. 2014;22(4):341–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jagp.2013.05.005. CN-00989215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brigham GS, Slesnick N, Winhusen TM, Lewis DF, Guo X, Somoza E. A randomized pilot clinical trial to evaluate the efficacy of Community Reinforcement and Family Training for Treatment Retention (CRAFT-T) for improving outcomes for patients completing opioid detoxification. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2014;138:240–3. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2014.02.013. CN-00980803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shinohara K, Tajika A, Imai H, Takeshima N, Hayasaka Y, Furukawa TA. Protocol registration and selective outcome reporting in recent psychiatry trials: new antidepressants and cognitive behavioural therapies. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2015;132(6):489–98. doi: 10.1111/acps.12502 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Knuppel H, Metz C, Meerpohl JJ, Strech D. How psychiatry journals support the unbiased translation of clinical research. A cross-sectional study of editorial policies. PLoS One. 2013;8(10):e75995 Epub 2013/10/23. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0075995 ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC3797836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mertens JR, Ward CL, Bresick GF, Broder T, Weisner CM. Effectiveness of nurse-practitioner-delivered brief motivational intervention for young adult alcohol and drug use in primary care in South Africa: a randomized clinical trial. Alcohol Alcohol. 2014;49(4):430–8. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agu030. CN-00995860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Campbell AN, Nunes EV, Matthews AG, Stitzer M, Miele GM, Polsky D, et al. Internet-delivered treatment for substance abuse: a multisite randomized controlled trial. The American journal of psychiatry. 2014;171(6):683–90. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2014.13081055 CN-00992413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hopewell S, Ravaud P, Baron G, Boutron I. Effect of editors' implementation of CONSORT guidelines on the reporting of abstracts in high impact medical journals: interrupted time series analysis. BMJ. 2012;344:e4178 Epub 2012/06/26. doi: 10.1136/bmj.e4178 ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC3382226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

Data Availability Statement

All relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files.