Abstract

Purpose

Health insurers offer plans covering a narrow subset of providers in an attempt to lower premiums and compete for consumers. However, narrow networks may limit access to high-quality providers, particularly those caring for patients with cancer.

Methods

We examined provider networks offered on the 2014 individual health insurance exchanges, assessing oncologist supply and network participation in areas that do and do not contain one of 69 National Cancer Institute (NCI)–Designated Cancer Centers. We characterized a network’s inclusion of oncologists affiliated with NCI-Designated Cancer Centers relative to oncologists excluded from the network within the same region and assessed the relationship between this relative inclusion and each network’s breadth. We repeated these analyses among networks offered in the same regions as the subset of 27 NCI-Designated Cancer Centers identified as National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) Cancer Centers.

Results

In regions containing NCI-Designated Cancer Centers, there were 13.7 oncologists per 100,000 residents and 4.9 (standard deviation [SD], 2.8) networks covering a mean of 39.4% (SD, 26.2%) of those oncologists, compared with 8.8 oncologists per 100,000 residents and 3.2 (SD, 2.1) networks covering on average 49.9% (SD, 26.8%) of the area’s oncologists (P < .001 for all comparisons). There was a strongly significant correlation (r = 0.4; P < .001) between a network’s breadth and its relative inclusion of oncologists associated with NCI-Designated Cancer Centers; this relationship held when considering only affiliation with NCCN Cancer Centers.

Conclusion

Narrower provider networks are more likely to exclude oncologists affiliated with NCI-Designated or NCCN Cancer Centers. Health insurers, state regulators, and federal lawmakers should offer ways for consumers to learn whether providers of cancer care with particular affiliations are in or out of narrow provider networks.

INTRODUCTION

To offer more price-competitive insurance products, health insurers increasingly market insurance plans that restrict access to providers—both physicians and hospitals.1-3 These narrow provider networks, or narrow networks, have been shown to have lower premiums,4 which may result from lowering provider reimbursement rates, selective contracting with providers associated with lower-cost enrollees,5,6 or exclusion of providers associated with higher-cost enrollees.7 Less research has described the relation between narrow networks and care quality; it is possible that narrow networks maintain or improve care quality,8,9 but there have also been concerns that narrow networks limit access to high-quality cancer care.7

Because cancer treatment and monitoring are costly10 and the cost and quality of cancer care vary widely,11-14 the effects of narrow networks may be most acutely observed among patients with cancer and oncologists who provide their care. Strong incentives exist for insurers to selectively contract with oncologists with whom they can negotiate lower prices and to systematically exclude those oncologists who are most likely to attract complex, costly cases.

National Cancer Institute (NCI)–Designated or National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) Cancer Centers are recognized for their scientific and research leadership, quality and safety initiatives, and access to expert physicians.15 NCCN Cancer Centers are particularly recognized for higher-quality care,16,17 and treatment at NCI-Designated Cancer Centers is associated with lower mortality than other hospitals, particularly among more severely ill patients and those with more advanced disease.18-20 Thus, NCI-Designated and NCCN Cancer Centers are likely to attract patients who require complex, costly care. Because of the name recognition and prestige associated with these designations, it is likely that these centers can exercise more market power in reimbursement negotiations with insurance companies and demand higher reimbursement rates for cancer services. For both of these reasons, oncologists associated with NCI-Designated or NCCN Cancer Centers might be more likely to be systematically excluded from narrow networks.

Thus, we assess the extent to which narrow networks in markets with NCI-Designated or NCCN Cancer Centers systematically exclude oncologists affiliated with those centers. This question has implications for whether narrow networks do indeed provide a tradeoff between cost and quality.

METHODS

Our study population consisted of oncologists in the United States. From a registry of all office-based practicing physicians from SK&A,21 oncologists were identified as physicians with a specialty designation of hematology/oncology or radiation oncology. We determined which oncologists were affiliated with one of the 69 NCI-Designated Cancer Centers on the basis of the oncologist’s listed hospital affiliations. We further identified a subset of 27 of these that NCCN has also designated as cancer centers. Because all NCCN Cancer Centers are also NCI-Designated Cancer Centers, the term NCI-Designated Cancer Centers in this article includes all centers in this larger group of cancer centers (inclusive of both NCI and NCCN Centers).

We define the market for cancer centers using the construct of a rating area. Rating areas consist of a set of counties within a state. There were 458 rating areas in 2014; 51 of these contained at least one of the 69 NCI-Designated Cancer Centers, whereas the subset of 27 NCCN Cancer Centers were located in 27 different rating areas. These rating areas are defined for the purposes of setting insurance premium rates, but because they are also a valid representation of the market in which insurance companies compete on price, for most rating areas they are a fair representation of the market from which cancer centers draw their patients. Thus, for the remainder of this article, we refer to rating areas as markets. To study the characteristics of these markets, we included population data from the American Community Survey, allowing us to determine each market’s total resident population and oncologist supply (oncologists per 100,000 residents). We identified all oncologists practicing in each market on the basis of the ZIP code of the location of their office as indicated on the SK&A file.

We focus on the clinically relevant and policy-relevant setting of the individual insurance exchanges associated with the Affordable Care Act, in which narrow network plans have been prominent. Using an integrated data set that lists all physician providers in each network offered on the insurance exchanges in 2014, which has been described previously,1 we estimate network size by market for our identified oncologists. This data set is a nearly complete representation of all networks offered on the exchanges, with validated physician lists for 355 of 395 unique provider networks. The breadth of each oncologist provider network was measured for each network in each market. Each network’s breadth in a particular market is estimated as the number of oncologists practicing in that market and participating in the network divided by the total number of oncologists practicing in that market. For each network, we include all markets in which at least one silver-level exchange insurance plan was sold using that network as its provider network.

We associate network breadth with whether the network is more or less likely to include high-quality oncologists (as measured by NCI-Designated or NCCN Cancer Center affiliation). We measure a network’s likelihood of including high-quality oncologists within each market by the proportion with NCI (or NCCN) affiliation among the market’s oncologists included in the network, divided by the proportion of those with NCI (or NCCN) affiliation among the market’s oncologists excluded from the network. Values greater than one indicate relative inclusion—and values less than one relative exclusion—of oncologists affiliated with NCI-Designated or NCCN Cancer Centers. Two versions of these inclusion measures were created—one reflecting participation in the broader set of NCI-Designated Cancer Centers and a second reflecting participation in the narrower subset of NCCN Cancer Centers. We then assessed the relationship between network breadth and the appropriate relative inclusion measure for all the networks (whether or not they included NCI-affiliated physicians) offered in any market containing an NCI-Designated Cancer Center as well as among the subset of networks offered in markets containing an NCCN Cancer Center.

Analyses were conducted using Stata version 14.1 (StataCorp, College Station, TX). The research was considered exempt by the University of Pennsylvania Institutional Review Board.

RESULTS

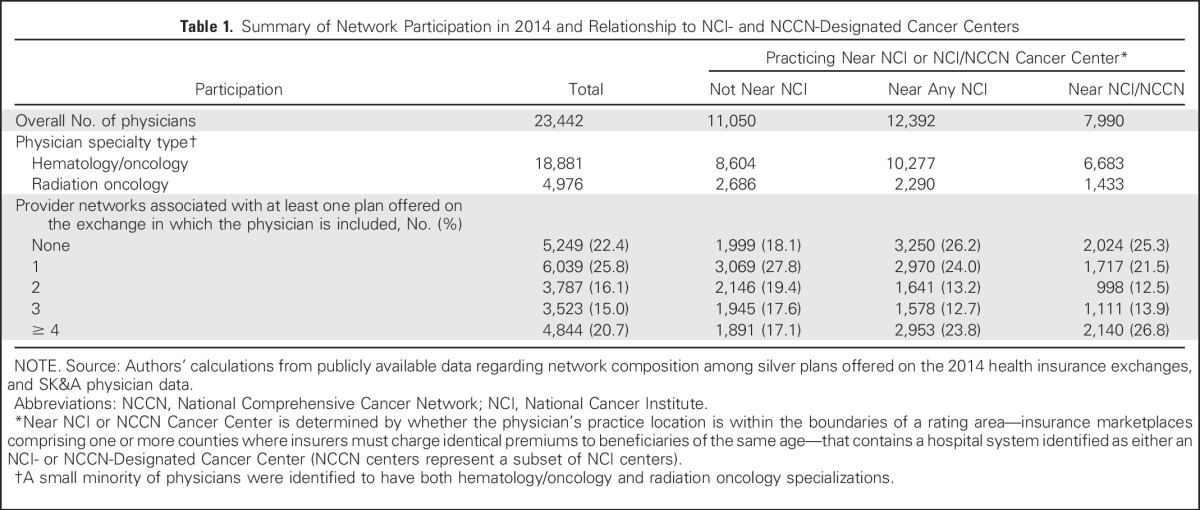

We identified 23,442 oncologists (3.4% of all unique physicians in the original integrated data set), of whom 12,392 (59.2%) were practicing in the 51 markets with at least one NCI-Designated Cancer Center; of these, 7,990 were practicing in the 27 markets containing centers also designated as NCCN Cancer Centers (Table 1). Approximately three-fourths of all oncologists were participating in at least one network offered on the health insurance exchanges. A higher proportion of oncologists practicing in markets with NCI-Designated Cancer Centers were excluded from all networks (26.2% v 18.1%; P < .001), but a higher proportion of these oncologists were also likely to be included in four or more networks (23.8% v 17.1%; P < .001).

Table 1.

Summary of Network Participation in 2014 and Relationship to NCI- and NCCN-Designated Cancer Centers

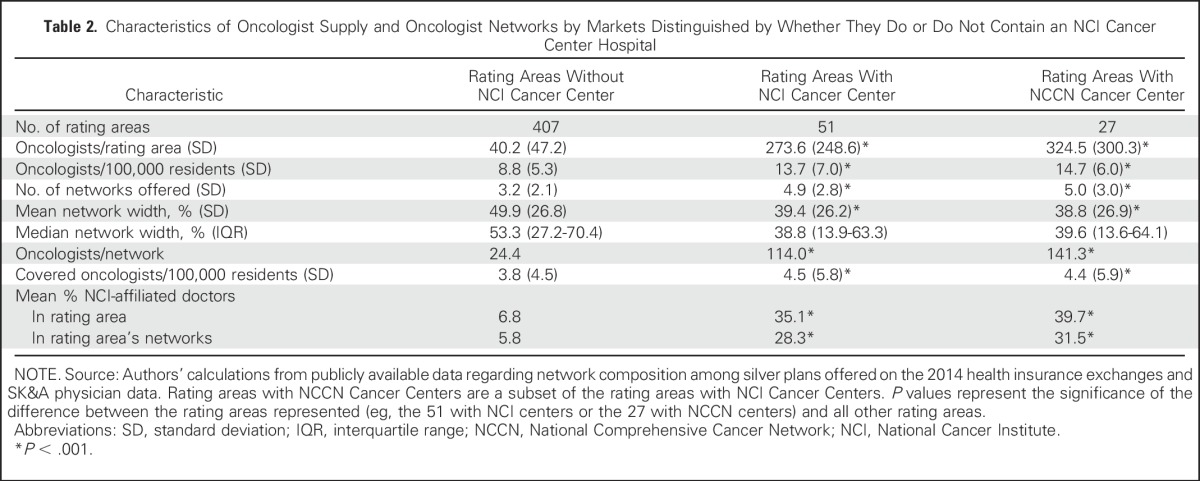

In the 51 markets that included NCI-Designated Cancer Centers, there were on average 4.9 (standard deviation [SD], 2.8) networks, compared with 3.2 (SD, 2.1) networks in markets without an NCI-Designated Cancer Center (Table 2). The overall oncologist supply was higher in markets that contained an NCI-Designated Cancer Center (13.7 [SD, 7.0] v 8.8 [SD, 5.3] oncologists per 100,000 residents), but networks in these markets were narrower on average (mean network width, 39.4% [SD, 26.2%] v 49.9% [SD, 26.8%], where lower proportions indicate narrower networks). The majority of networks in markets that contained an NCI-Designated Cancer Center included fewer than half of the oncologists practicing in the market. Despite this narrowness, the average number of covered oncologists per 100,000 residents was higher among networks offered in markets with an NCI Cancer Center (4.5 [SD, 5.8] v 3.8 [SD 4.5]). All differences between markets that did and did not contain NCI-Designated Cancer Centers were highly significant (P < .001).

Table 2.

Characteristics of Oncologist Supply and Oncologist Networks by Markets Distinguished by Whether They Do or Do Not Contain an NCI Cancer Center Hospital

When we examined the subset of markets that contained an NCCN Cancer Center, we found similar results, with oncologist supply, network breadth, and mean number of covered oncologists per 100,000 residents comparable to the corresponding statistics in markets that contained a non-NCCN NCI-Designated Cancer Center. There were no significant differences between the two subsets of markets (those containing NCI-Designated Cancer Centers that were or were not also designated as NCCN centers).

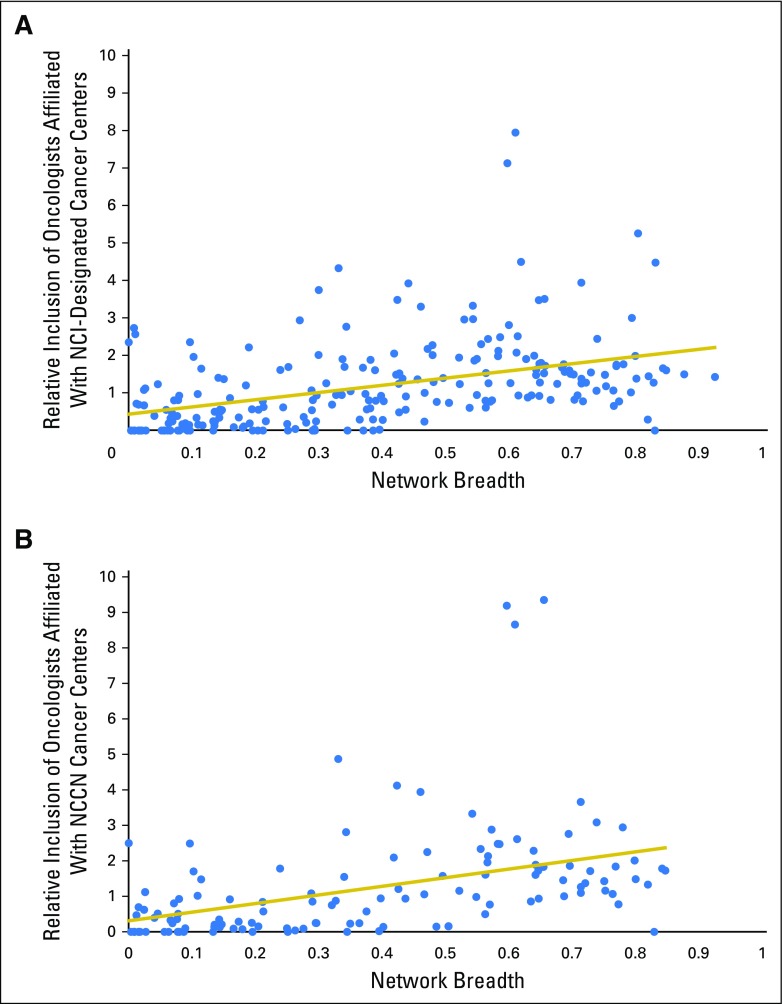

To examine the relationship between a network’s breadth and its relative inclusion of oncologists affiliated with an NCI-Designated Cancer Center, we focused only on those networks offered in one of the 51 markets that contained at least one NCI-Designated Cancer Center. For every market that included an NCI-Designated Cancer Center within its physical boundary, we included all networks that were associated with at least one plan sold in that market. There were multiple networks (33 of the 248 included in our analysis) that did not contain a single physician affiliated with an NCI center; these networks were narrower, on average, than those that included at least one NCI physician (mean, 14.1% of local oncologists in-network, compared with a mean of 42.3% among networks that included at least one NCI-affiliated oncologist). Figure 1A displays a significant correlation between oncology network breadth and our relative inclusion measure (r = 0.44; P < .001), indicating that narrower oncology networks have fewer oncologists affiliated with NCI-Designated Cancer Centers. Figure 1B displays the results of the same analysis limited to just the networks offered within the subset of 27 markets containing an NCCN Cancer Center, where the results were nearly identical (r = 0.42; P < .001).

Fig 1.

(A) Network breadth and relative inclusion of oncologists affiliated with National Cancer Institute (NCI)–Designated Cancer Centers. (B) Network breadth and relative inclusion of oncologists affiliated with National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) Cancer Centers. Network breadth is defined as the proportion of a rating area’s physicians included in a network. Relative inclusion of NCI-affiliated oncologists is determined by the proportion of oncologists affiliated with NCI-Designated Cancer Centers in each network, divided by the proportion of oncologists with NCI affiliation excluded from that network from within the same rating area.

DISCUSSION

We find that narrower provider networks have a higher likelihood of systematically excluding oncologists affiliated with NCI-Designated or NCCN Cancer Centers. These hospitals are recognized for their high-quality clinical cancer care, education, and research programs. This finding suggests that narrow provider networks may not just have fewer providers from which to choose; in addition, the more limited list of available providers may not offer the same quality care as those providers who have been excluded from the network. This highlights a critical tradeoff consumers face when purchasing a narrow network plan: consumers may benefit from the fact that narrow networks generally have lower premiums, but they may face reduced access to the higher-quality providers in their market.

This tradeoff, however, may not extend to other types of health care or across all narrow networks. One study examining performance on process-of-care quality measures among hospitals in California found that hospitals included in narrow networks performed as well as or better than hospitals excluded from narrow networks.8 In addition, some narrow networks are limited to well-integrated, high-quality physician groups such as Kaiser Permanente, which suggests that narrow networks could be a useful tool to ensure higher-quality health care.9

Nevertheless, our findings reaffirm and extend prior calls for accurate information about providers in health plan networks and are relevant to replacement proposals for the Affordable Care Act, which foster shoppable insurance in both the individual and group markets.22 In 2016, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services enacted rules for publishing user-friendly provider directories that include a provider’s location, contact information, specialty, medical group, and any hospital affiliations.23 Specifically, we also call for provider directories to reflect indicators of care quality and clinical expertise, such as—for providers of cancer care—NCI or NCCN affiliation and other care quality designations.

We also found that the density of covered oncologists (oncologists per 100,000 residents) was similar between markets with and without NCI-Designated or NCCN Cancer Centers, even though networks were narrower (the majority included fewer than half of oncologists) in markets that contained an NCI-Designated or NCCN Cancer Center. This finding somewhat reassuringly suggests that overall access to providers of cancer care may be similar in markets with and without NCI-Designated or NCCN Cancer Centers, even as oncologists affiliated with such centers are more likely to be excluded from narrower networks. It remains to be seen whether there exist similar associations between network breadth and the reputation or prestige of oncologists’ affiliated hospitals in regions that do not contain NCI-Designated Cancer Centers.

This study has limitations. Although we demonstrate an association between network breadth and exclusion of NCI-Designated or NCCN Cancer Centers, we cannot conclude that insurers consciously exclude these physicians at higher rates because of their NCI designation or whether the exclusion results from a correlated factor. For example, it is possible that group practice size (unavailable in our data set) is associated with market power and pricing and is also correlated with NCI or NCCN affiliation. We also cannot identify differences in actual care quality among cancer centers from our data sets, nor is it possible to ascribe higher quality or better outcomes to patients treated at NCI-Designated or NCCN Cancer Centers; such designation is only one marker of quality. Future research should extend our work on access to providers of cancer care to examine the relationship between narrow networks and cancer care quality, outcomes, and spending.

Last, our study focuses on narrow network plans in the individual insurance exchanges and, thus, is most directly applicable to the individual (consumer) rather than the group (employer) market. Benchmarking network sizes found among exchange plans to those found among standard commercial plans offered in the same regions would allow a comparison between the two,8 but, to our knowledge, these data are unavailable at the national level. However, narrow networks are becoming more common in the group market as well, and insurers may well use the same strategies for lowering premiums and competing for customers in both markets.

In summary, narrower provider networks are more likely to exclude oncologists affiliated with NCI-Designated or NCCN Cancer Centers. Health insurers, state regulators, and federal lawmakers should offer ways for consumers to learn more about the providers of cancer care and their affiliations when considering narrow network plans.

Footnotes

Supported by the National Cancer Institute Grant No. P30-CA016520, National Cancer Institute Grant No. K07-CA163616, American Cancer Society (ACS) Grant No. RSGI-12697, National Institute on Aging Grant No PO1 AG19783, and Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Grant No. 30768.

See accompanying Editorial on page 3095

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conception and design: All authors

Financial support: Justin E. Bekelman, Daniel Polsky

Collection and assembly of data: Laura Yasaitis, Daniel Polsky

Data analysis and interpretation: All authors

Manuscript writing: All authors

Final approval of manuscript: All authors

Accountable for all aspects of the work: All authors

AUTHORS' DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Relation Between Narrow Networks and Providers of Cancer Care

The following represents disclosure information provided by authors of this manuscript. All relationships are considered compensated. Relationships are self-held unless noted. I = Immediate Family Member, Inst = My Institution. Relationships may not relate to the subject matter of this manuscript. For more information about ASCO's conflict of interest policy, please refer to www.asco.org/rwc or ascopubs.org/jco/site/ifc.

Laura Yasaitis

No relationship to disclose

Justin E. Bekelman

Consulting or Advisory Role: Gerson Lehrman Group

Daniel Polsky

Research Funding: Pfizer (Inst)

REFERENCES

- 1.Polsky D, Weiner J. The skinny on narrow networks in health insurance marketplace plans. University of Pennsylvania LDI, 2015. www.rwjf.org/en/library/research/2015/06/the-skinny-on-narrow-networks-in-health-insurance-marketplace-pl.html [Google Scholar]

- 2. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2015.0885. Claxton G, Rae M, Panchal N, et al: Health benefits in 2015: Stable trends in the employer market. Health Aff (Millwood) 34:1779-1788, 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. McKinsey & Company: Hospital networks: Evolution of the configurations on the 2015 exchanges. http://healthcare.mckinsey.com/sites/default/files/2015HospitalNetworks.pdf.

- 4.Polsky D, Cidav Z, Swanson A: Marketplace plans with narrow physician networks feature lower monthly premiums than plans with larger networks. Health Aff (Millwood) 35:1842-1848, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Atwood A, Lo Sasso AT: The effect of narrow provider networks on health care use. J Health Econ 50:86-98, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Gruber J, McKnight R: Controlling health care costs through limited network insurance plans: Evidence from Massachusetts state employees. National Bureau of Economic Research, Cambridge, MA, 2014.

- 7.Schleicher SM, Mullangi S, Feeley TW: Effects of narrow networks on access to high-quality cancer care. JAMA Oncol 2:427-428, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Haeder SF, Weimer DL, Mukamel DB: California hospital networks are narrower in marketplace than in commercial plans, but access and quality are similar. Health Aff (Millwood) 34:741-748, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Haeder SF, Weimer DL, Mukamel DB: Narrow networks and the Affordable Care Act. JAMA 314:669-670, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mariotto AB, Yabroff KR, Shao Y, et al. : Projections of the cost of cancer care in the United States: 2010-2020. J Natl Cancer Inst 103:117-128, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cooperberg MR, Broering JM, Carroll PR: Time trends and local variation in primary treatment of localized prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol 28:1117-1123, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brooks GA, Li L, Uno H, et al. : Acute hospital care is the chief driver of regional spending variation in Medicare patients with advanced cancer. Health Aff (Millwood) 33:1793-1800, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McWilliams JM, Dalton JB, Landrum MB, et al. : Geographic variation in cancer-related imaging: Veterans Affairs health care system versus Medicare. Ann Intern Med 161:794-802, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Makarov DV, Soulos PR, Gold HT, et al. : Regional-level correlations in inappropriate imaging rates for prostate and breast cancers: Potential implications for the Choosing Wisely campaign. JAMA Oncol 1:185-194, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.National Cancer Institute : NCI-Designated Cancer Centers. http://www.cancer.gov/research/nci-role/cancer-centers

- 16.Rajput A, Romanus D, Weiser MR, et al. : Meeting the 12 lymph node (LN) benchmark in colon cancer. J Surg Oncol 102:3-9, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Buchholz TA, Theriault RL, Niland JC, et al. : The use of radiation as a component of breast conservation therapy in National Comprehensive Cancer Network Centers. J Clin Oncol 24:361-369, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pfister DG, Rubin DM, Elkin EB, et al. : Risk adjusting survival outcomes in hospitals that treat patients with cancer without information on cancer stage. JAMA Oncol 1:1303-1310, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Onega T, Duell EJ, Shi X, et al. : Influence of NCI cancer center attendance on mortality in lung, breast, colorectal, and prostate cancer patients. Med Care Res Rev 66:542-560, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Friese CR, Silber JH, Aiken LH: National Cancer Institute Cancer Center designation and 30-day mortality for hospitalized, immunocompromised cancer patients. Cancer Invest 28:751-757, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dunn A, Shapiro AH: Do physicians possess market power? J Law Econ 57:159-193, 2014 [Google Scholar]

- 22. Haeder SF, Weimer DL, Mukamel DB: Secret shoppers find access to providers and network accuracy lacking for those in Marketplace and commercial plans. Health Aff (Millwood) 35:1160-1166, 2016. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 23. Jaffe S: Obamacare, Private Medicare Plans Must Keep Updated Doctor Directories in 2016. Kaiser Health News. http://khn.org/news/health-exchange-medicare-advantage-plans-must-keep-updated-doctor-directories-in-2016/