ABSTRACT

Lamin A (LA) is a critical structural component of the nuclear lamina. Mutations within the LA gene (LMNA) lead to several human disorders, most striking of which is Hutchinson-Gilford Progeria Syndrome (HGPS), a premature aging disorder. HGPS cells are best characterized by an abnormal nuclear morphology known as nuclear blebbing, which arises due to the accumulation of progerin, a dominant mutant form of LA. The microtubule (MT) network is known to mediate changes in nuclear morphology in the context of specific events such as mitosis, cell polarization, nucleus positioning and cellular migration. What is less understood is the role of the microtubule network in determining nuclear morphology during interphase. In this study, we elucidate the role of the cytoskeleton in regulation and misregulation of nuclear morphology through perturbations of both the lamina and the microtubule network. We found that LA knockout cells exhibit a crescent shape morphology associated with the microtubule-organizing center. Furthermore, this crescent shape ameliorates upon treatment with MT drugs, Nocodazole or Taxol. Expression of progerin, in LA knockout cells also rescues the crescent shape, although the response to Nocodazole or Taxol treatment is altered in comparison to cells expressing LA. Together these results describe a collaborative effort between LA and the MT network to maintain nuclear morphology.

KEYWORDS: HGPS, lamin A, nuclear shape, microbutuble, progerin

Introduction

Lamin A (LA), a type V intermediate filament encoded by the LMNA gene, is a key component of the nuclear lamina.1 The lamina supports the nuclear envelope, allowing the nucleus to resist mechanical perturbations.2,3 LA directly interacts with chromosomes and nuclear regulatory proteins, implicating the nuclear lamina in key cellular processes such as apoptosis, chromatin organization, and gene expression.4-9

Mutations in the LMNA gene have been associated with a heterogeneous, rare group of hereditary diseases collectively termed laminopathies that include Emery–Dreifuss Muscular Dystrophy, Dunnigan-type familial partial lipodystrophy, dilated cardiomyopathy, and Hutchinson-Gilford Progeria Syndrome (HGPS).1,5,10,11 Among these laminopathies, HGPS has been extensively studied due to its striking clinical phenotypes including osteoporosis, loss of subcutaneous fat, alopecia, and joint stiffening after 12 months of age.5,12-14 HGPS arises due to the accumulation of a mutant LA isoform termed progerin which anchors to the nuclear membrane and leads to thickening of the nuclear lamina, loss of heterochromatin, alterations in histone methylation, gene misregulation, and genomic instability.4,6,15-21 Most Evidently, the accumulation of progerin results in an abnormal nuclear morphology termed nuclear blebbing.16 Nuclear blebbing appears to drive the pathology of HGPS, as treatments that improve blebbing have been associated with ameliorated HGPS cellular phenotypes.10,22-28 A change in nuclear shape is also suggested to be a hallmark of lamin mutations that lead to other laminopathies.29

The nucleus is not an isolated system. Prior studies have shown that the cytoskeleton directly influences nuclear shape in fundamental cellular processes.30,31 The most extreme example is the Microtubule (MT) facilitated nuclear breakdown during mitosis.32 Furthermore, during cell migration, a filamentous actin structure known as the actin cap compresses and supports the nucleus.33 Studies investigating granulopoiesis found that the MT network mediates nuclear lobulation.34 Other studies have focused on MT influences during migration/positioning. In Drosophila follicle cells, individual MT fibers push the nucleus creating local indentations resulting in nuclear “wriggling”.35 In Drosophila oocytes, the dorsal-ventral axis is polarized by nucleus migration. This process is mediated by the MTOC which pushes the nucleus causing an indentation.36 A direct connection between the nuclear lamina and the cytoskeleton has been established through LINC complexes, transmembrane proteins that span the nuclear membrane and bind to both.37 These studies, as well as others, have focused on event specific microtubule-nucleus interactions.33,34,37-41 In comparison, relatively little is known about how the equilibrium nuclear morphology is affected by the cytoskeleton, especially in laminopathies. Interestingly, NAT10 inhibitor, remodelin has been associated with improved nuclear morphology and cellular fitness in HGPS cells through a mechanism targeting the MT organizing center (MTOC),42 which suggests a role for the cytoskeleton in the nuclear blebbing phenotype in HGPS.

In this study, we investigate the interplay between microtubules and the nuclear lamina to elucidate the role of the cytoskeleton in maintaining normal nuclear morphology. We find that the MT network in the presence of LA is necessary for appropriate nuclear morphology. The absence of LA led to MT-driven nuclear abnormalities. Furthermore, the presence of progerin led to the altered MT-nucleus interactions. Together, these results suggest that normal nuclear shape is dependent upon balanced interactions between both cytoskeletal and lamin networks.

Results

Loss of LA results in the MTOC-associated crescent-shaped nuclei

The MT network is dynamic, with MTs growing and pushing, while also pulling on their surrounding via molecular motors.43 LA has previously been described as a rigid material.31,44 We, therefore, hypothesized that if MT network dynamicity and LA rigidity exhibit some interplay, then LA removal would result in MT driven abnormalities. To test this hypothesis, we characterized LA knockout (LA−/−) fibroblast nuclei and compared them to LA+/+ fibroblast nuclei.

To accurately and quantitatively determine the nuclear shape, we applied a described previously method for nuclear measurements.45,46 This program reports nuclear morphology as a measure of local invaginations typically associated with blebs and nuclear deformations. Mean negative curvature (MNC), one of the reported measures, is defined as the absolute value of the average negative curvature (negative when measured relative to the center of the nucleus) excluding all positive curvature values, i.e. all regions where the nucleus bulges outward. While it is counterintuitive to not measure outward bulges, our previous work clearly showed that blebs are best identified from their surrounding inward invaginations.45,46 Indeed, nuclei we would identify as more abnormal by visual inspection exhibit higher MNC.

Using lamin B1 (LB1) immunofluorescence staining, we observed that LA−/− cells more frequently exhibited a crescent shaped nuclear morphology compared with LA+/+ cells (Fig. 1A). We then counted over 100 randomly selected nuclei and found that the frequency of crescent-shaped nuclei was significantly higher in LA−/− cells than LA+/+ cells (Fig. 1B). The crescent shape of the nucleus was associated with gamma tubulin localization to the arc of the crescent (Fig. 1C and D), suggesting that the MTOC may be involved in this nuclear abnormality in the absence of LA.

Figure 1.

Loss of LA results in an MTOC associated crescent shape. (A) Representative confocal immunofluorescence images of LA −/− and LA +/+ cells. Green = lamin B1; Blue = DAPI. (B) Frequency of crescent-shaped nuclei in LA−/− and LA+/+ cells. N > 100 nuclei per population. *** p <0.001. Counted by 3 independent observers. Error bars are the standard deviation. (C) Representative confocal images of MTOC colocalization with crescent invagination in LA−/− cells. Green = gamma tubulin; Blue = DAPI. (D) Frequency of LA−/− and LA+/+ crescent-shaped nuclei colocalized with gamma tubulin. N >100 nuclei per population. Counted by 3 independent observers. Error bars are standard deviation. Error bars are the standard deviation. (E) Distribution of LA−/− and LA +/+ nuclear morphology as quantified by mean negative curvature. Density denotes cell count. N > 150. (F) Distribution of LA−/− and LA +/+ nuclear morphology as quantified by nuclear area. The area measurements are normalized to LA−/−. (G) Clustering of LA−/− and LA+/+ nuclei with a dotted line denoting the boundary between the 2 populations. Both metrics are normalized to LA−/−.

Nuclear shape analysis showed that LA−/− nuclei exhibited increased mean negative curvature (Fig. 1E) and reduced nuclear area (Fig. 1F), suggesting that LA−/− nuclei displayed worsened morphology. The differences were significant enough allowing for robust identification of a boundary between the 2 conditions (Fig. 1G). When using all the 5 metrics of nuclear shape (i.e., MNC, area, eccentricity, solidity, and tortuosity) for classification, the classification accuracy is quite high at 88%, with a 10% likelihood of classifying a single LA+/+ cell as LA−/−, and a 13% chance of classifying a single LA−/− cell as LA+/+. These results show that LA is necessary for appropriate nuclear morphology, and further suggests that the MTOC drives this change in nuclear shape.

Disruption of the MT network improves LA−/− nuclear morphology

To test whether the MT network facilitated abnormal nuclear morphology observed in LA−/− cells, we treated LA −/− and LA +/+ cells with classical MT drugs Nocodazole (NOC) and Taxol (TX). We used NOC to depolymerize MTs and used TX to stabilize and polymerize MTs. LA−/− and LA+/+ fibroblasts were treated with increasing concentrations of either NOC or TX for 2 hours and then stained for MTs. Appropriate concentrations (4μM NOC and 2μM) were identified by changes in MT organization in LA−/− and LA+/+ fibroblasts (Fig S1 and S2).

We observed improvement of LA−/− nuclear morphology following either NOC or TX treatment (Fig. 2A). Quantitative image analysis showed no change in MNC for LA+/+ cells (Fig. 2B), indicating under the experimental condition, either of these treatments significantly affects the nuclear shape in healthy cells. Interestingly, a decrease in mean negative curvature for LA−/− cells was observed in NOC or TX treatments. This result further suggests that the MT network is not needed to maintain the rounded morphology of healthy cells, but plays a role in facilitating LA−/− nuclear abnormalities.

Figure 2.

Disruption of the microtubule network improves abnormal LA−/− nuclear morphology. (A) Representative confocal images of LA−/− and LA+/+ cells treated with Mock, 4µM Nocodazole (NOC), or 2µM Taxol (TX). Green = Lamin B1; Blue = DAPI. (B-D) Nuclear morphology quantifications of LA−/− and LA+/+ cells treated with Mock, 4μM NOC, and 2μM TX. (B) Mean negative curvature, (C) Area, (D) Volume measurements. N > 300 nuclei per population. Data is represented as mean with 95% confidence intervals. All values are normalized to LA−/− mock treated. *** p < 0.001. (E-G) Mean negative curvature by area contour plots. (E) LA−/− treated nuclei. (F) LA+/+ treated nuclei (G) Both LA−/− and LA+/+ nuclei excluding mock treated. N > 200 nuclei per population. Both metrics are normalized to LA−/− Mock. Dotted line depicts boundary between LA−/− and LA+/+. (H) Representative confocal images of LA−/− and LA+/+ cells treated with Mock, 4µM Nocodazole (NOC), or 2µM Taxol (TX). Red = Gamma-tubulin; Blue = DAPI.

Image analysis further showed that nuclear area decreased for both LA−/− and LA+/+ cells following NOC treatment and that the area increased following TX treatment of LA+/+ cells (Fig. 2C). To determine whether MT affected the projected area or the volume of the nucleus, we took Z-stack images of each nucleus and measured nuclear volume using a built-in function in Volocity (Perkin Elmer, Waltham, MA). We analyzed over 300 nuclei per condition and found that in these experiments, differences in the nuclear area are associated with changes in nuclear volume (Fig. 2D). Using our previously identified boundary (Fig. 1G), we asked whether NOC and TX shifted LA−/− nuclei toward LA+/+ morphology in all of the parameters we measure. The analysis agrees with the observed changes in MNC alone; LA−/− cells treated with NOC or TX become more LA+/+ like while LA+/+ treated cells exhibit little change (Fig. 2E–G).

We were curious about whether any of these drug treatments caused a disassociation between the nucleus and MTOC allowing for the rescue of the crescent shape. Staining with anti-gamma tubulin antibodies revealed no such disassociation (Fig. 2H). Altogether, these results show that the MTs play a role in driving LA−/− nuclear abnormality and furthermore demonstrate that LA plays a role in mediating nucleus-MT interactions.

Expression of LA and progerin in LA−/− cells partially rescues the crescent shape

To further elucidate the role of LA in the nucleus-MT interactions, we conducted a rescue experiment by transducing LA−/− cells with LA-GFP through lentivirus infection (Fig S3). As we previously reported,28,47,48 the expression level of LA-GFP from lentiviruses is moderate and comparable to the endogeneous LA/C (Fig S3). Interestingly, we found that LA-GFP expression in LA−/− cells quickly and effectively rescued nuclear morphology (Fig. 3A and B) and GFP-alone control did not improve the crescent nuclear shape (Fig. 3A and B). As LA−/− cells may have considerable perturbations in the organization of actin, vimentin and other structural components,49 this rescue experiment validated the direct causal relationship between lack of LA and the crescent shape nuclear morphology.

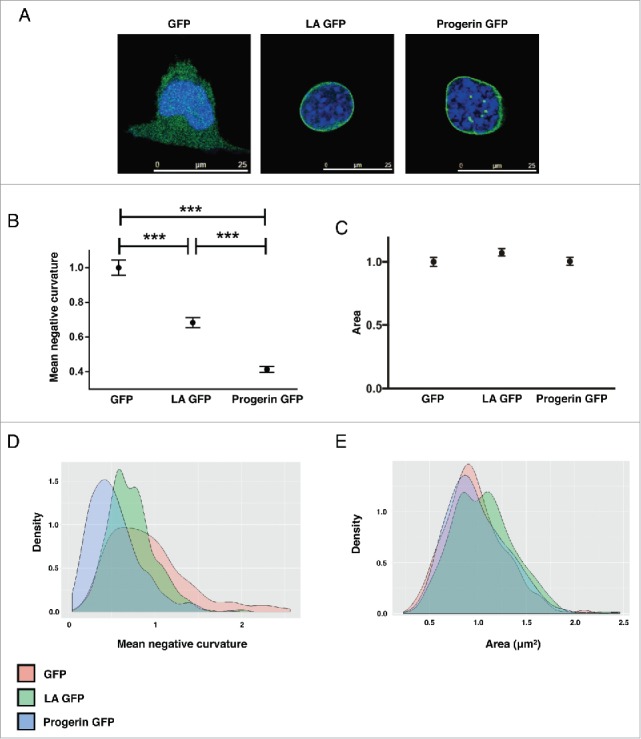

Figure 3.

Ectopic expression of LA-GFP or Progerin-GFP partially rescues abnormal LA −/− nuclear morphology. (A) Representative confocal immunofluorescence images of LA −/− nuclei transfected with GFP, LA-GFP, or progerin-GFP. Green = GFP; Blue = DAPI. (B-C) Nuclear morphology quantification of GFP-expressing LA−/− nuclei. (B) Mean negative curvature, and (C) Area. N > 300 nuclei per population. Data is normalized to GFP-expressing LA−/− samples. *** p < 0.001. (D-E) Distribution of nuclear morphology quantification in LA−/− cells expressing GFP, LA-GFP or progerin-GFP.

HGPS is a well-studied laminopathy that arises due to a dominant mutant LA isoform termed progerin. Nuclear blebbing is considered a hallmark phenotype in HGPS cells.5,16,50-52 To test whether progerin expression alone is sufficient for inducing nuclear blebbing, we also transduced LA−/− cells with progerin-GFP expressing lentivirus and quantified changes in nuclear morphology. Our initial observations unexpectedly revealed that progerin-GFP overexpression partially rescued the LA−/− morphological phenotype (Fig. 3A). These observations were consistent with automated analysis, which showed decreased MNC (Fig. 3B and D) in progerin-GFP expressing cells. Considering that progerin is a truncated form of LA, this rescue is likely due to progerin retaining some LA functionality. Additionally, it is important to note that our transfected nuclei did not contain LA (Fig S3). It is possible that nuclear blebs arise due to interaction between LA and progerin rather than just progerin accumulation (see discussion).

No significant changes in the nuclear area were observed in either LA-GFP or progerin-GFP expressing LA−/− cells in comparison to GFP alone control cells (Fig. 3C and E). Neither did the lentiviral transduction cause any observable changes with MT organization and MTOC position (Fig S4).

Progerin-GFP alters responses to NOC and TX drug treatments

We then tested whether progerin-GFP expressing cells responded to NOC and TX treatment in a similar fashion as LA-GFP expressing cells. As expected, GFP expressing LA−/− cells showed improved nuclear morphology in response to NOC and TX treatments (Fig. 4A and D). Interestingly, LA-GFP expressing cells exhibited similar behavior to drug treatment as LA+/+ cells (Fig. 4B and D), reiterating that both the MT network and LA are necessary for appropriate nuclear morphology. Surprisingly, progerin-GFP cells did not mimic LA-GFP cells' response to NOC and TX. LB1 immunofluorescence staining showed that progerin-GFP cells had worsened nuclear morphology in response to NOC and further improved morphology following TX (Fig. 4C). These visual impressions were further confirmed by nuclear quantitative analysis. MNC increased in progerin-GFP cells in response to NOC and decreased in response to TX, supporting our immunofluorescence images (Fig. 4D). Notably, both LA-GFP and progerin-GFP expressing nuclei exhibited decreased area following NOC treatment and increased area in response to TX (Fig 4E and F), reminiscent of the LA+/+ cells (Fig. 2C). We confirmed that all of these models responded to drug treatments as expected (Fig S5) and observed that the MTOC remained associated positioning (Fig S6). Together, these results suggest that progerin, despite partially rescuing LA−/− nuclear morphology, alters nucleus-MT interactions.

Figure 4.

Progerin-GFP alters the response to cytoskeletal drugs. (A-C) Representative confocal immunofluorescence images of LA −/− nuclei transfected with (A) GFP, (B) LA-GFP, and (C) Progerin-GFP treated with either mock, 4μM NOC, or 2μM TX. Green = GFP; Red = Lamin B1; Blue = DAPI. (D-F) Quantification of transfected LA−/− nuclei (D) Mean negative curvature, (E) Area with Nocodazole treatment, and (F) Area with Taxol treatment. N >150 nuclei for each quantification. Data plotted as mean with 95% confidence intervals. All metrics are normalized to LA−/− GFP. **p < 0.01; ***p <0.001.

Discussion

In this study, we investigated the relationship between the MT network and the nuclear lamina in an attempt to better understand how the cytoskeleton modulates nuclear shape. We applied high-throughput automated nuclear shape analysis program to determine changes in nuclear morphology after MT and LA perturbations. We used progerin as a disease model to understand how altered lamina impacted cytoskeletal influence on the nucleus. Understanding how the cytoskeleton and nuclear lamina interact to sustain nuclear shape, as well as the impact of progerin on this interplay provides insights into HGPS pathology and treatments from a mechanical perspective.

Local MT influence on nuclear morphology

Loss of LA resulted in an abnormal nuclear morphology, with crescent-shaped nuclei where the center of the crescent is associated with the MTOC. The MTOC's position provides insights into the mechanical balance within the cell as the MTOC location is based upon balancing forces of the emanating MT fibers.53,54 When these forces are balanced, the MTOC is at equilibrium. If the MTOC is not at this point, the forces are unbalanced, and the MTOC will move back to the balanced state. Thus, the MTOC is said to have a “center seeking” behavior (Fig. 5).

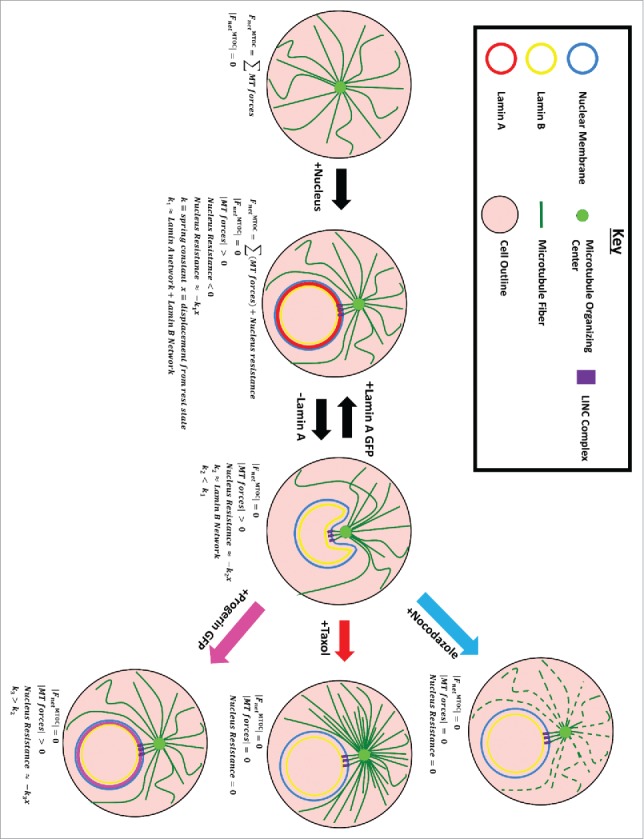

Figure 5.

Local Microtubule-Nucleus interaction. We hypothesize that the microtubule-organizing center (MTOC) locally deforms the nucleus mediated through LINC complexes. Force produced by the MTOC is normally resisted by the nucleus, specifically LA. Removal of LA leads to the invagination which can be rescued by progerin or LA expression. Nuclear morphology can also be rescued by Nocodazole and Taxol treatments which reduce MTOC force production.

Since the nucleus prevents such centering of the MTOC, it is likely that the MTOC locally pushes against the nucleus, but that the nucleus is still enough to resist the MTOC yet preserve normal nuclear shape. The paucity of lamins leading to nuclear invagination centered about the MTOC was proposed in one model of HL-60 cell differentiation.34 Specifically, it was observed that retinoic acid differentiation of HL-60 cells leads to invagination/lobulation of the nucleus in a MT-dependent mechanism.34 Our LA knockout and LA-GFP rescue (Fig. 3) experiments suggest that it is the LA layer that retains a concave nuclear shape against a pushing MTOC. The importance of LA in providing nuclear stiffness against MTOC driven deformations is further supported by the change in nuclear morphology during differentiation of monocytes into macrophages. Monocytes normally lack LA and exhibit crescent-shaped nuclei, however upon differentiation into macrophages they express LA and return to a circular nuclear morphology.55

It is worth noting that our results disagree with findings in another publication,56 in which a disassociation between MTOC and the nucleus in LA−/− cells was documented, and the authors pointed to an emerin dimer as the anchor of these 2 together. We confirmed that our cells are completely negative for LA (Fig S3). Since emerin requires LA to target to the nucleus,9 it would appear unlikely to be involved in anchoring the MTOC within our system.

Rather than weaken and strengthen the nuclear rigidity, we can also alter the pushing of the microtubule network. Perturbations of the MT fibers via NOC and TX resulted in improved nuclear morphology (Fig. 2), even for LA−/− cells. This indicates a reduced force about the MTOC (Fig. 5). There is some concern with whether the usage of MT drugs could inhibit mitosis impinging on our analysis. Considering the shortness of our treatment (2 hours) in comparison to the cell doubling time (18–24 hours) we do not expect significant biasing of results.

Progerin is traditionally associated with an abnormal nuclear morphology. However, when we transfected progerin-GFP into LA−/− nuclei, we found rescue of the crescent morphology rather than the presence of nuclear blebs (Figs. 3 and 4). Considering that progerin is a truncated form of LA, this rescue is likely due to progerin retaining some LA functionality. Additionally, it is important to note that our transfected nuclei did not contain LA (Fig S3). It is possible that nuclear blebs arise due to interaction between LA and progerin rather than just progerin accumulation. Lamin interactions leading to nuclear blebs is not an unprecedented idea. Prior work has mathematically modeled nuclear blebbing as a mechanical phenomenon arising due to LA and LB interactions.57 A recent study provides experimental supports to this notion by identifying compounds that efficiently blocked progerin-lamin A/C binding and alleviated nuclear deformation and HGPS phenotypes in animal models.55

A working model

We summarize these findings with a schematic explained below (Fig. 5). The microtubule network is anchored to the MTOC, and thus the MTOC experiences forces due to microtubule polymerization, as well as forces due to molecular motors attached to microtubules that pull on the surrounding. Application of NOC and TX affect the MT and their force production. NOC depolymerizes MT and TX “freezes” them both of which reduces the forces pushing onto the MTOC (Fig S7).

The nucleus also applies a force onto the MTOC, and we approximate this interaction as a spring whose stiffness is a function of lamin composition.58 Removal of LA decreases nucleus stiffness, changing the equilibrium resulting in a local concavity/crescent shaped nucleus. This shape can be rescued by altering the force balance. If the MTs are perturbed via NOC or TX, the force about the MTOC pushing into the nucleus is vastly reduced or near zero resulting in amelioration of shape. If the spring is stiffened via LA-GFP or progerin-GFP transfection, the MTOC faces a stronger opposing force resulting in more rounded nuclear shape (Fig. 3). One open question is whether this more rounded nuclear shape may go hand in hand with amelioration of the disease phenotypes of laminopathies.

Global MT influence on nuclear morphology

The MT cytoskeleton is composed of more than just the MTOC: it is a global network found throughout the cell. Therefore, the MT network should influence nuclear morphology beyond the large deformations seen near the MTOC. We found that NOC treatment always resulted in smaller nuclei (Fig. 2C, D, and Fig. 4E) and that TX resulted in increased nuclear size for LA+/+, LA-GFP, or progerin-GFP nuclei (Fig. 2C, D, and Fig. 4F). These findings suggest that while the MTOC pushes against the nucleus, other MT may also pull on the nucleus, with the overall effect that the MT network expands the nucleoskeleton, thereby helping to maintain its shape.

To pull on the nucleus, the MT cytoskeleton must be anchored to it. However, the MT cytoskeleton does not directly interact with the nuclear membrane or lamina, but rather is connected to the lamina by transmembrane LINC complexes. LINC complexes SUN1-Nesprin3α along with BPAG159-62 connect LA to the MT network and are stabilized when interacting with LA.63,64 Thus, LA−/− cells provide at best a reduced anchoring for the MT network to the nucleus. Indeed, the size of LA−/− nuclei did not increase after TX treatment (Fig. 2C, D and Fig. 4F).

Rather than removal of the LA, its structure can also be altered, specifically in HGPS. LA is released from the inner nuclear membrane following ZMPSTE24-mediated removal of its farnesyl group, while progerin remains anchored to the inner membrane. Thus a LA-dominant nuclear lamina is organized differently than a progerin-dominant nuclear lamina within the nucleus. Normally the LA forms a spherical mesh along with Lamin B, another intranuclear lamin. The meshes are rather homogenous with some interconnectedness.65,66 Progerin creates a disrupted network that disrupts the LB network and blends these 2 networks together.67 Previous studies show that distribution of the nuclear lamina plays a role in HGPS pathology, emphasizing the importance of lamina organization in preserving nuclear morphology.66 Indeed, we find that Progerin-GFP nuclei responded differently than LA-GFP nuclei following NOC and TX treatments. NOC treatment resulted in less rounded nuclear morphology while TX improved MNC (Fig. 4D). Our study suggests that appropriate nuclear lamina organization is necessary for proper MT-mediated forces on the nucleus and thereby nuclear morphology.

Materials and methods

Cell lines and drug treatments

LA knockout (LA −/−) along with control LA (LA+/+) mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) were obtained from Dr. Colin L. Stewart54 and cultured in Dulbecco's Modified Eagle's Medium (Lonza) supplemented with 10% FBS (Gemini- Bio-Products) under 5% CO2 at 37°C. Nocodazole, Taxol or DMSO was diluted to specified concentrations in 10% FBS DMEM media and then co-cultured with cells for 2 hours. Following treatment, cells were immediately fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde/PBS.

Immunofluorescence staining

For immunofluorescence, cells were grown in glass-bottom dishes, fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde/PBS for 25min at room temperature, permeabilized with 0.5% Triton X-100/PBS for 5 min and then incubated in blocking solution (4% BSA/TBS) overnight at 4°C. Cells were then incubated with primary antibodies overnight at 4°C, followed by incubation with fluorescently conjugated secondary antibody for 1h at room temperature. Fluorescence was visualized by either a Nikon Spinning Disc Confocal or a Leica SP5-X system.

Antibodies

Antibodies used in this study included: goat anti-Lamin B antibody (M20, Santa Cruz), mouse anti-α-tubulin antibody (DM1a, Santa Cruz) and mouse anti-ɣ-tubulin antibody (019K4794, Sigma).

Lentivirus production

LA-GFP and progerin-GFP expressing lentiviral plasmids were constructed as previously reported.43 In short, LA or progerin cDNA was subcloned into a pHR-SIN-CSGW lentiviral vector. For lentiviral production pHR-LA-GFP-SIN-CSGW or pHR-progerin-GFP-SIN-CSGW vectors was transfected into 293T cells together with both pHR-CMV-8.2ΔR, and pCMV-VSVG via Fugene 6 (Promega, E2692). The viruses were collected 48 hours after transfection, filtered through 0.45 µm filters, tittered through FACS and ultimately stored at −80°C.

Image analysis

Images were analyzed by a custom in house MATLAB program described previously.42 In short, the program outlines nuclear boundaries and extracts shape measures, such as boundary curvature thus allowing for a more sensitive, controlled analysis as compared with traditional hand counting.

Nuclei morphology was characterized through 4 different metrics. Mean negative curvature is defined as the average negative curvature on the boundary of each nuclei Area is measured as the number of pixels enclosed by a nucleus boundary and then converted to µm using image resolution. Eccentricity is defined as 1 – the ratio of the nucleus' major axis over the minor axis. Solidity is defined as the ratio of the area over convex hull area.

Statistical analysis

Data was analyzed by a 2-tailed Student's t-test assuming unequal variance, a p-value less than 0.05 was considered significant. Multiple comparison corrections were applied where appropriate. A chi-square test was conducted to compare the number of crescent-shaped nuclei in LA −/− and LA +/+ fibroblasts.

Supplementary Material

Abbreviations

- HGPS

Hutchinson-Gilford Progeria Syndrome

- LA

Lamin A

- LA −/−

Lamin A Knockout

- LB1

Lamin B1

- MNC

Mean Negative Curvature

- MT

Microtubule

- MTOC

Microtubule Organizing Center

- NOC

Nocodazole

- TX

Taxol

Disclosure of potential conflicts of interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

References

- [1].Eriksson M, Brown WT, Gordon LB, Glynn MW, Singer J, Scott L, Erdos MR, Robbins CM, Moses TY, Berglund P, et al.. Recurrent de novo point mutations in lamin A cause Hutchinson-Gilford progeria syndrome. Nature 2003; 423:293-8; PMID:12714972; https://doi.org/ 10.1038/nature01629 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Lammerding J, Schulze PC, Takahashi T, Kozlov S, Sullivan T, Kamm RD, Stewart CL, Lee RT. Lamin A/C deficiency causes defective nuclear mechanics and mechanotransduction. J Clin Invest 2004; 113:370-8; PMID:14755334; https://doi.org/ 10.1172/JCI200419670 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Worman HJ, Courvalin JC. How do mutations in lamins A and C cause disease? J Clin Invest 2004; 113:349-51; PMID:14755330; https://doi.org/ 10.1172/JCI20832 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Shumaker DK, Dechat T, Kohlmaier A, Adam SA, Bozovsky MR, Erdos MR, Eriksson M, Goldman AE, Khuon S, Collins FS, et al.. Mutant nuclear lamin A leads to progressive alterations of epigenetic control in premature aging. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2006; 103:8703-8; PMID:16738054; https://doi.org/ 10.1073/pnas.0602569103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Capell BC, Collins FS. Human laminopathies: nuclei gone genetically awry. Nat Rev Genet 2006; 7:940-52; PMID:17139325; https://doi.org/ 10.1038/nrg1906 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].McCord RP, Nazario-Toole A, Zhang H, Chines PS, Zhan Y, Erdos MR, Collins FS, Dekker J, Cao K. Correlated alterations in genome organization, histone methylation, and DNA-lamin A/C interactions in Hutchinson-Gilford progeria syndrome. Genome Res 2013; 23:260-9; PMID:23152449; https://doi.org/ 10.1101/gr.138032.112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Ly DH, Lockhart DJ, Lerner RA, Schultz PG. Mitotic misregulation and human aging. Science 2000; 287:2486-92; PMID:10741968; https://doi.org/ 10.1126/science.287.5462.2486 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Marji J, O'Donoghue SI, McClintock D, Satagopam VP, Schneider R, Ratner D, Worman HJ, Gordon LB, Djabali K. Defective lamin A-Rb signaling in Hutchinson-Gilford Progeria Syndrome and reversal by farnesyltransferase inhibition. PLoS One 2010; 5:e11132; PMID:20559568; https://doi.org/ 10.1371/journal.pone.0011132 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Wu D, Flannery AR, Cai H, Ko E, Cao K. Nuclear localization signal deletion mutants of lamin A and progerin reveal insights into lamin A processing and emerin targeting. Nucleus 2014; 5:66-74; PMID:24637396; https://doi.org/ 10.4161/nucl.28068 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Bonne G, Di Barletta MR, Varnous S, Becane HM, Hammouda EH, Merlini L, Muntoni F, Greenberg CR, Gary F, Urtizberea JA, et al.. Mutations in the gene encoding lamin A/C cause autosomal dominant Emery-Dreifuss muscular dystrophy. Nat Genet 1999; 21:285-8; PMID:10080180; https://doi.org/ 10.1038/6799 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Cao H, Hegele RA. Nuclear lamin A/C R482Q mutation in canadian kindreds with Dunnigan-type familial partial lipodystrophy. Hum Mol Genet 2000; 9:109-12; PMID:10587585; https://doi.org/ 10.1093/hmg/9.1.109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Gordon LB, Harling-Berg CJ, Rothman FG. Highlights of the 2007 Progeria Research Foundation scientific workshop: progress in translational science. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2008; 63:777-87 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Gordon LB, McCarten KM, Giobbie-Hurder A, Machan JT, Campbell SE, Berns SD, Kieran MW. Disease progression in Hutchinson-Gilford progeria syndrome: impact on growth and development. Pediatrics 2007; 120:824-33; PMID:17908770; https://doi.org/ 10.1542/peds.2007-1357 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Merideth MA, Gordon LB, Clauss S, Sachdev V, Smith AC, Perry MB, Brewer CC, Zalewski C, Kim HJ, Solomon B, et al.. Phenotype and course of Hutchinson-Gilford progeria syndrome. N Engl J Med 2008; 358:592-604; PMID:18256394; https://doi.org/ 10.1056/NEJMoa0706898 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Goldman RD, Shumaker DK, Erdos MR, Eriksson M, Goldman AE, Gordon LB, Gruenbaum Y, Khuon S, Mendez M, Varga R, et al.. Accumulation of mutant lamin A causes progressive changes in nuclear architecture in Hutchinson-Gilford progeria syndrome. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2004; 101:8963-8; PMID:15184648; https://doi.org/ 10.1073/pnas.0402943101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Cao K, Capell BC, Erdos MR, Djabali K, Collins FS. A lamin A protein isoform overexpressed in Hutchinson-Gilford progeria syndrome interferes with mitosis in progeria and normal cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2007; 104:4949-54; PMID:17360355; https://doi.org/ 10.1073/pnas.0611640104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Dechat T, Pfleghaar K, Sengupta K, Shimi T, Shumaker DK, Solimando L, Goldman RD. Nuclear lamins: major factors in the structural organization and function of the nucleus and chromatin. Genes Dev 2008; 22:832-53; PMID:18381888; https://doi.org/ 10.1101/gad.1652708 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Dechat T, Shimi T, Adam SA, Rusinol AE, Andres DA, Spielmann HP, Sinensky MS, Goldman RD. Alterations in mitosis and cell cycle progression caused by a mutant lamin A known to accelerate human aging. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2007; 104:4955-60; PMID:17360326; https://doi.org/ 10.1073/pnas.0700854104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Goldman RD, Gruenbaum Y, Moir RD, Shumaker DK, Spann TP. Nuclear lamins: building blocks of nuclear architecture. Genes Dev 2002; 16:533-47; PMID:11877373; https://doi.org/ 10.1101/gad.960502 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Stancheva I, Schirmer EC. Nuclear envelope: connecting structural genome organization to regulation of gene expression. Adv Exp Med Biol 2014; 773:209-44; PMID:24563350 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Liu B, Wang J, Chan KM, Tjia WM, Deng W, Guan X, Huang JD, Li KM, Chau PY, Chen DJ, et al.. Genomic instability in laminopathy-based premature aging. Nat Med 2005; 11:780-5; PMID:15980864; https://doi.org/ 10.1038/nm1266 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Yang SH, Bergo MO, Toth JI, Qiao X, Hu Y, Sandoval S, Meta M, Bendale P, Gelb MH, Young SG, et al.. Blocking protein farnesyltransferase improves nuclear blebbing in mouse fibroblasts with a targeted Hutchinson-Gilford progeria syndrome mutation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2005; 102:10291-6; PMID:16014412; https://doi.org/ 10.1073/pnas.0504641102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Glynn MW, Glover TW. Incomplete processing of mutant lamin A in Hutchinson-Gilford progeria leads to nuclear abnormalities, which are reversed by farnesyltransferase inhibition. Hum Mol Genet 2005; 14:2959-69; PMID:16126733; https://doi.org/ 10.1093/hmg/ddi326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Yang SH, Meta M, Qiao X, Frost D, Bauch J, Coffinier C, Majumdar S, Bergo MO, Young SG, Fong LG. A farnesyltransferase inhibitor improves disease phenotypes in mice with a Hutchinson-Gilford progeria syndrome mutation. J Clin Invest 2006; 116:2115-21; PMID:16862216; https://doi.org/ 10.1172/JCI28968 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Mallampalli MP, Huyer G, Bendale P, Gelb MH, Michaelis S. Inhibiting farnesylation reverses the nuclear morphology defect in a HeLa cell model for Hutchinson-Gilford progeria syndrome. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2005; 102:14416-21; PMID:16186497; https://doi.org/ 10.1073/pnas.0503712102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Cao K, Graziotto JJ, Blair CD, Mazzulli JR, Erdos MR, Krainc D, Collins FS. Rapamycin reverses cellular phenotypes and enhances mutant protein clearance in Hutchinson-Gilford progeria syndrome cells. Sci Transl Med 2011; 3:89ra58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Graziotto JJ, Cao K, Collins FS, Krainc D. Rapamycin activates autophagy in Hutchinson-Gilford progeria syndrome: implications for normal aging and age-dependent neurodegenerative disorders. Autophagy 2012; 8:147-51; PMID:22170152; https://doi.org/ 10.4161/auto.8.1.18331 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Xiong ZM, Choi JY, Wang K, Zhang H, Tariq Z, Wu D, Ko E, LaDana C, Sesaki H, Cao K. Methylene blue alleviates nuclear and mitochondrial abnormalities in progeria. Aging Cell 2016; 15:279-90; PMID:26663466; https://doi.org/ 10.1111/acel.12434 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Davidson PM, Lammerding J. Broken nuclei–lamins, nuclear mechanics, and disease. Trends Cell Biol 2014; 24:247-56; PMID:24309562; https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.tcb.2013.11.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Gruenbaum Y, Margalit A, Goldman RD, Shumaker DK, Wilson KL. The nuclear lamina comes of age. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2005; 6:21-31; PMID:15688064; https://doi.org/ 10.1038/nrm1550 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Dahl KN, Ribeiro AJ, Lammerding J. Nuclear shape, mechanics, and mechanotransduction. Circ Res 2008; 102:1307-18; PMID:18535268; https://doi.org/ 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.173989 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Beaudouin J, Gerlich D, Daigle N, Eils R, Ellenberg J. Nuclear envelope breakdown proceeds by microtubule-induced tearing of the lamina. Cell 2002; 108:83-96; PMID:11792323; https://doi.org/ 10.1016/S0092-8674(01)00627-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Kim DH, Cho S, Wirtz D. Tight coupling between nucleus and cell migration through the perinuclear actin cap. J Cell Sci 2014; 127:2528-41; PMID:24639463; https://doi.org/ 10.1242/jcs.144345 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Olins AL, Olins DE. Cytoskeletal influences on nuclear shape in granulocytic HL-60 cells. BMC Cell Biol 2004; 5:30; PMID:15317658; https://doi.org/ 10.1186/1471-2121-5-30 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Szikora S, Gaspar I, Szabad J. ‘Poking’ microtubules bring about nuclear wriggling to position nuclei. J Cell Sci 2013. 126:254-62; PMID:23077179; https://doi.org/ 10.1242/jcs.114355 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Zhao T, Graham O, Raposo A, St. Johnston D. Growing microtubules push the oocyte nucleus to polarize the drosophila dorsal-ventral axis. Science (New York, NY) 2012; 336:999-1003; https://doi.org/ 10.1126/science.1219147 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Crisp M, Liu Q, Roux K, Rattner JB, Shanahan C, Burke B, Stahl PD, Hodzic D. Coupling of the nucleus and cytoplasm: role of the LINC complex. J Cell Biol 2006; 172:41-53; PMID:16380439; https://doi.org/ 10.1083/jcb.200509124 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Levy JR, Holzbaur EL. Dynein drives nuclear rotation during forward progression of motile fibroblasts. J Cell Sci 2008; 121:3187-95; PMID:18782860; https://doi.org/ 10.1242/jcs.033878 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Georgatos SD, Pyrpasopoulou A, Theodoropoulos PA. Nuclear envelope breakdown in mammalian cells involves stepwise lamina disassembly and microtubule-drive deformation of the nuclear membrane. J Cell Sci 1997; 110 ( Pt 17):2129-40; PMID:9378763 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].McGregor AL, Hsia CR, Lammerding J. Squish and squeeze-the nucleus as a physical barrier during migration in confined environments. Curr Opin Cell Biol 2016; 40:32-40; PMID:26895141; https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.ceb.2016.01.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Fruleux A, Hawkins RJ. Physical role for the nucleus in cell migration. J Phys Condens Matter 2016; 28:363002; PMID:27406341; https://doi.org/ 10.1088/0953-8984/28/36/363002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Larrieu D, Britton S, Demir M, Rodriguez R, Jackson SP. Chemical inhibition of NAT10 corrects defects of laminopathic cells. Science 2014; 344:527-32; PMID:24786082; https://doi.org/ 10.1126/science.1252651 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Tsai MY, Wiese C, Cao K, Martin O, Donovan P, Ruderman J, Prigent C, Zheng Y. A Ran signalling pathway mediated by the mitotic kinase Aurora A in spindle assembly. Nat Cell Biol 2003; 5:242-8; PMID:12577065; https://doi.org/ 10.1038/ncb936 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Swift J, Ivanovska IL, Buxboim A, Harada T, Dingal PC, Pinter J, Pajerowski JD, Spinler KR, Shin JW, Tewari M, et al.. Nuclear lamin-A scales with tissue stiffness and enhances matrix-directed differentiation. Science (New York, NY) 2013; 341:1240104; https://doi.org/ 10.1126/science.1240104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Driscoll MK, Albanese JL, Xiong ZM, Mailman M, Losert W, Cao K. Automated image analysis of nuclear shape: what can we learn from a prematurely aged cell? Aging (Albany NY) 2012; 4:119-32; PMID:22354768; https://doi.org/ 10.18632/aging.100434 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Candia J, Maunu R, Driscoll M, Biancotto A, Dagur P, McCoy JP Jr, Sen HN, Wei L, Maritan A, Cao K, et al.. From cellular characteristics to disease diagnosis: uncovering phenotypes with supercells. PLoS Comput Biol 2013; 9:e1003215; PMID:24039568; https://doi.org/ 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1003215 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Wu D, Yates PA, Zhang H, Cao K. Comparing lamin proteins post-translational relative stability using a 2A peptide-based system reveals elevated resistance of progerin to cellular degradation. Nucleus 2016; 7:585-96; PMID:27929926; https://doi.org/ 10.1080/19491034.2016.1260803 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Zhang H, Sun L, Wang K, Wu D, Trappio M, Witting C, Cao K. Loss of H3K9me3 Correlates with ATM Activation and Histone H2AX Phosphorylation Deficiencies in Hutchinson-Gilford Progeria Syndrome. PLoS One 2016; 11:e0167454; PMID:27907109; https://doi.org/ 10.1371/journal.pone.0167454 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Broers JL, Peeters EA, Kuijpers HJ, Endert J, Bouten CV, Oomens CW, Baaijens FP, Ramaekers FC. Decreased mechanical stiffness in LMNA−/− cells is caused by defective nucleo-cytoskeletal integrity: implications for the development of laminopathies. Hum Mol Genet 2004; 13:2567-80; PMID:15367494; https://doi.org/ 10.1093/hmg/ddh295 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Cao K, Blair CD, Faddah DA, Kieckhaefer JE, Olive M, Erdos MR, Nabel EG, Collins FS. Progerin and telomere dysfunction collaborate to trigger cellular senescence in normal human fibroblasts. J Clin Invest 2011; 121:2833-44; PMID:21670498; https://doi.org/ 10.1172/JCI43578 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Capell BC, Olive M, Erdos MR, Cao K, Faddah DA, Tavarez UL, Conneely KN, Qu X, San H, Ganesh SK, et al.. A farnesyltransferase inhibitor prevents both the onset and late progression of cardiovascular disease in a progeria mouse model. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2008; 105:15902-7; PMID:18838683; https://doi.org/ 10.1073/pnas.0807840105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Capell BC, Erdos MR, Madigan JP, Fiordalisi JJ, Varga R, Conneely KN, Gordon LB, Der CJ, Cox AD, Collins FS. Inhibiting farnesylation of progerin prevents the characteristic nuclear blebbing of Hutchinson-Gilford progeria syndrome. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2005; 102:12879-84; PMID:16129833; https://doi.org/ 10.1073/pnas.0506001102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Holy TE, Dogterom M, Yurke B, Leibler S. Assembly and positioning of microtubule asters in microfabricated chambers. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1997; 94:6228-31; PMID:9177199; https://doi.org/ 10.1073/pnas.94.12.6228 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Reinsch S, Gonczy P. Mechanisms of nuclear positioning. J Cell Sci 1998; 111 ( Pt 16):2283-95; PMID:9683624 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Lee SJ, Jung YS, Yoon MH, Kang SM, Oh AY, Lee JH, Jun SY, Woo TG, Chun HY, Kim SK, et al.. Interruption of progerin-lamin A/C binding ameliorates Hutchinson-Gilford progeria syndrome phenotype. J Clin Invest 2016; 126:3879-93; PMID:27617860; https://doi.org/ 10.1172/JCI84164 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Lee J, Hale CM, Panorchan P, Khatau SB, George J, Tseng Y, Stewart CL, Hodzic D, Wirtz D. Nuclear lamin A/C deficiency induces defects in cell mechanics, polarization, and migration. Biophys J 2007; 93:2542-52; PMID:17631533; https://doi.org/ 10.1529/biophysj.106.102426 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Funkhouser CM, Sknepnek R, Shimi T, Goldman AE, Goldman RD, Olvera de la Cruz M. Mechanical model of blebbing in nuclear lamin meshworks. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2013; 110:3248-53; PMID:23401537; https://doi.org/ 10.1073/pnas.1300215110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Dahl KN, Kahn SM, Wilson KL, Discher DE. The nuclear envelope lamina network has elasticity and a compressibility limit suggestive of a molecular shock absorber. J Cell Sci 2004; 117:4779-86; PMID:15331638; https://doi.org/ 10.1242/jcs.01357 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Hale CM, Shrestha AL, Khatau SB, Stewart-Hutchinson PJ, Hernandez L, Stewart CL, Hodzic D, Wirtz D. Dysfunctional connections between the nucleus and the actin and microtubule networks in laminopathic models. Biophys J 2008; 95:5462-75; PMID:18790843; https://doi.org/ 10.1529/biophysj.108.139428 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Ketema M, Sonnenberg A. Nesprin-3: a versatile connector between the nucleus and the cytoskeleton. Biochem Soc Trans 2011; 39:1719-24; PMID:22103514; https://doi.org/ 10.1042/BST20110669 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Roux KJ, Crisp ML, Liu Q, Kim D, Kozlov S, Stewart CL, Burke B. Nesprin 4 is an outer nuclear membrane protein that can induce kinesin-mediated cell polarization. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2009; 106:2194-9; PMID:19164528; https://doi.org/ 10.1073/pnas.0808602106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Ketema M, Wilhelmsen K, Kuikman I, Janssen H, Hodzic D, Sonnenberg A. Requirements for the localization of nesprin-3 at the nuclear envelope and its interaction with plectin. J Cell Sci 2007; 120:3384-94; PMID:17881500; https://doi.org/ 10.1242/jcs.014191 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Chang W, Worman HJ, Gundersen GG. Accessorizing and anchoring the LINC complex for multifunctionality. J Cell Biol 2015; 208:11-22; PMID:25559183; https://doi.org/ 10.1083/jcb.201409047 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Kim Y, Sharov AA, McDole K, Cheng M, Hao H, Fan CM, Gaiano N, Ko MS, Zheng Y. Mouse B-type lamins are required for proper organogenesis but not by embryonic stem cells. Science 2011; 334:1706-10; PMID:22116031; https://doi.org/ 10.1126/science.1211222 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].Goldberg MW, Fiserova J, Huttenlauch I, Stick R. A new model for nuclear lamina organization. Biochem Soc Trans 2008; 36:1339-43; PMID:19021552; https://doi.org/ 10.1042/BST0361339 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].Shimi T, Pfleghaar K, Kojima S, Pack CG, Solovei I, Goldman AE, Adam SA, Shumaker DK, Kinjo M, Cremer T, et al.. The A- and B-type nuclear lamin networks: microdomains involved in chromatin organization and transcription. Genes Dev 2008; 22:3409-21; PMID:19141474; https://doi.org/ 10.1101/gad.1735208 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [67].Delbarre E, Tramier M, Coppey-Moisan M, Gaillard C, Courvalin JC, Buendia B. The truncated prelamin A in Hutchinson-Gilford progeria syndrome alters segregation of A-type and B-type lamin homopolymers. Hum Mol Genet 2006; 15:1113-22; PMID:16481358; https://doi.org/ 10.1093/hmg/ddl026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.