Abstract

This report describes a secondary analysis of data from a comprehensive intervention project which included training and structural changes in three Baby Homes in St. Petersburg, Russian Federation. Multiple mediator models were tested according to the Baron and Kenny (1986) causal-steps approach to examine whether caregiver-child interaction quality, number of caregiver transitions, and group size mediated the effects of the intervention on children’s attachment behaviors and physical growth. The study utilized a subsample of 163 children from the original Russian Baby Home project who were between 11 and 19 months at the time of assessment. Results from comparisons of the training and structural changes versus no intervention conditions are presented. Caregiver-child interaction quality and the number of caregiver transitions fully mediated the association between intervention condition and attachment behavior. No other mediation was found. Results suggest that the quality of interaction between caregivers and children in institutional care is of primary importance to children’s development, but relationship context may play less direct mediational role, supporting caregiver-child interactions.

Keywords: Institutional care, caregiver-child interactions, attachment, physical growth

According to estimates, there are over 2 million orphans and vulnerable children living in institutional care worldwide (UNICEF, 2009). Institutionalized children often experience significant delays in cognitive, physical, and social development (Bakermans-Kranenburg et al., 2011; Dobrova-Krol, van IJzendoorn, Bakermans-Kranenburg, Cyr, & Juffer, 2008; Engle et al., 2007; Gunnar, 2001; Johnson et al., 2010; Smyke et al., 2007; The St. Petersburg—USA Orphanage Research Team, 2005; van IJzendoorn, Bakermans-Kranenburg, & Juffer, 2007). Most of these children live in depriving environments with limited caregiver-child interaction, limited stimulation, high children-adult ratios, and inconsistent caregivers (Rosas & McCall, 2011; van IJzendoorn et al., 2011). Research suggests that the quality of caregiver-child interaction in particular, rather than nutrition and medical care, leads to these poor outcomes (McCall, 2011; Smyke et al., 2007; The St. Petersburg—USA Orphanage Research Team, 2008).

However, little research has examined the role of relationship context in children’s development in institutional care. Relationship context refers to any past and present characteristics of the caregiving environment that may influence the formation or maintenance of a caregiver-child relationship. An intervention in Baby Homes (BHs) in St. Petersburg, Russian Federation, indicated that relationship context contributed to children’s development (The St. Petersburg—USA Orphanage Research Team, 2008). The present article reports secondary analyses of data from this study to determine whether caregiver-child interaction quality and two specific components of the relationship context, stability of caregivers and group size, mediated the relationship between intervention condition and children’s attachment and physical growth outcomes.

Institutional Characteristics

Since the discovery of extremely deficient conditions in Romanian orphanages in the 1990s, there has been great concern over deprivation in institutional care. Institutional care environments may vary in level of deprivation depending on whether they provide adequate health care and nutrition, cognitive stimulation, and opportunities for children to form relationships with caregivers (Gunnar, 2001). In most institutions, children experience few interactions with caregivers, those interactions are often poor in quality, and children are cared for in large groups with high children-adult ratios, experience multiple caregiver changes, and are deprived of appropriate social and emotional stimulation (Rosas & McCall, 2011; van IJzendoorn et al., 2011). These characteristics likely deny children necessary opportunities to form stable, trusting relationships with caregivers (Dobrova-Krol et al., 2008).

Caregiver-Child Interactions

Observational studies of institutional care have revealed that caregivers rarely interact with children in warm, sensitive, contingently responsive ways. Because of the high children-adult ratios and large group sizes, caregivers spend nearly all their time with children in routine care, such as bathing, feeding, and toileting, and very little time interacting with the children in play (Dobrova-Krol et al., 2008; The St. Petersburg-USA Orphanage Research Team, 2005; van IJzendoorn et al., 2011). In one study of Russian BHs, caregivers spent only 16% of their time engaged in group or one-on-one activities with children (Tirella et al., 2007). On average, children birth to three years old spent half of their waking hours not engaged in interactions with either peers or caregivers. In another study of the BHs involved in the current study, caregivers only interacted with infants 3–10 months old for 12.4 minutes during a 3-hour period, and nearly half of interaction was during routine feeding (Muhamedrahimov, 1999). When caregivers are required to interact with children for routine care, they demonstrate little warmth, sensitivity, or affection (The St. Petersburg-USA Orphanage Research Team, 2005; van IJzendoorn et al., 2011).

Relationship Context

Even when caregiver-child interactions are of good quality, the relationship context may limit the amount of such interactions with individual children and may limit children’s opportunities to form lasting quality relationships with their caregivers.

Group size and children-adult ratio

Children in institutions are typically cared for in large groups with high children-adult ratios. There are often 9–16 children per ward, although in some cases the group size may be much larger, and 8 children per caregiver, although it can be much higher (Rosas & McCall, 2011; van IJzendoorn et al., 2011). Such conditions limit the time caregivers have to care for children beyond meeting their basic physical needs.

Transitions

Children typically experience numerous transitions throughout their stay in institutional care. Many institutions separate children into groups based on their age or developmental level, so children transition to a new ward with new peers and caregivers when they reach a certain age or milestone (i.e., walking). Such transitions typically occur two to three times in the first 3 years of life (The St. Petersburg-USA Orphanage Research Team, 2005). In addition, many institutions have high caregiver turnover, caregivers may get as much as 55 days of vacation a year, and substitutes are not consistently assigned to the same ward (The St. Petersburg-USA Orphanage Research Team, 2005, 2008; van IJzendoorn et al., 2011). The collective result is that children may experience 60–100 different caregivers over their first two years of life in the institution (The St. Petersburg-USA Orphanage Research Team, 2008). The inconsistency of caregivers across time, and even day to day, may limit children’s opportunities to form long-term relationships with their caregivers and may affect their development.

Developmental Delays

Institutionalized children often experience delays in physical, cognitive, and social-emotional development (Bakermans-Kranenburg et al., 2011; Dobrova-Krol et al., 2008; Engle et al., 2007; Gunnar, 2001; Johnson et al., 2010; Smyke et al., 2007; The St. Petersburgh-USA Orphanage Research Team, 2005; van IJzendoorn et al., 2007). Increased time in the institution is related to greater delays, and children placed in adoptive or foster families and those experiencing interventions in institutions often experience catch-up following the change in care quality (Bakermans-Kranenburg et al., 2011; Engle et al., 2007; Gunnar, 2001; Johnson et al., 2010; Smyke et al., 2007; The St. Petersburgh-USA Orphanage Research Team, 2008; van IJzendoorn et al., 2007). This suggests that that institutional deprivation may be responsible for the early delays.

Attachment

Bowlby (1969) proposed that there is an evolutionary drive for infants and young children to maintain proximity to a competent caregiver, especially in times of threat or uncertainty. Over time in typical families, infants form an internal working model of their individual caregivers’ role as comforter and protector based on the consistency of the caregivers’ responses to the infants’ bids for attention. As a result, the infants can use such caregivers as dependable secure bases from which to venture out to explore the environment.

Given limited caregiver-child interaction in institutions, it is not surprising that many institutionalized infants and toddlers have poor attachment relationships with caregivers. Specifically, across four studies, 73% of institutionalized children were categorized as having disorganized attachment to their caregivers in Strange Situation type assessments; this is in stark contrast to about 15% of family-reared children who are categorized this way (Bakermans-Kranenburg, 2011, Dobrova-Krol et al., 2010; The St. Petersburg-USA Orphanage Research Team, 2008; Vorria et al., 2003; Zeanah et al., 2005). Attachment theory posits that disorganized infants view caregivers as a source of care and comfort but also a source of anxiety and fear (Bakermans-Kranenburg et al., 2011). However, institutional caregivers are more likely unavailable than an expected source of anxiety (Bakermans-Kranenburg et al., 2011). Due to high children-adult ratios and multiple caregiver changes, children in institutions may not have enough individual interactions with any one caregiver to form an organized attachment (Ainsworth, 1979).

Physical Development

A large number of children reared in institutions experience poor physical growth and stunting (Dobrova-Krol et al., 2008; Engle et al., 2007; Gunnar, 2001; Johnson et al., 2010; van IJzendoorn et al., 2007). Stunting is defined as having a height-for-age of two or more standard deviations below the norm for parent-reared children (Grantham-McGregor et al., 2007; Walker et al., 2007). It is negatively associated with indices of secure attachment, play quality, positive affect, attention skills, social skills, cognitive development, and school achievement (Grantham-McGregor et al., 2007).

Although poor physical growth is usually attributed to poor nutritional intake, research with institutionalized and post-institutionalized children has indicated that social factors play a significant role (Dobrova-Krol et al., 2008; Engle et al., 2007; Gunnar, 2001; Johnson et al., 2010, van IJzendoorn et al., 2007). According to the psychosocial short stature hypothesis, social-emotional deprivation leads to increased stress, which, if chronic, can dysregulate the hypothalamus-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis inhibiting the production of growth hormone (Johnson & Gunnar, 2011; Talbot et al., 1947; The St. Petersburg-USA Orphanage Research Team, 2008; Widdowson, 1951). Some of the most convincing evidence for the psychosocial short stature hypothesis has come from The St. Petersburg-USA Orphanage Research Team’s (2008) Russian BH study. Children who had experienced improved caregiving quality following an intervention of caregiver training grew physically at greater rates than children who had not experienced improvements in care, despite no changes in nutrition or medical care. Also, studies in which institutionalized children are transferred to adoptive or foster families have documented substantial physical growth catch-up (Dobrova-Krol et al., 2008; Engle et al., 2007; Johnson et al., 2010), but improved social-behavioral caregiving in these studies is likely confounded with improved nutrition (Engle et al., 2007).

Role of Caregiving Quality and Relationship Context in Development

Some existing research from Early Childhood Education (ECE) settings suggests that the relationship context characteristics, such as transitions between caregivers and group size, do influence children’s development. However, to date, there is limited evidence to indicate that these specific effects are present within institutional care environments.

Caregiver Transitions

Theoretically, if a child forms an attachment to a caregiver and develops a working model of expectations, that child should be better able to handle the transition to a new caregiver. However, without a secure attachment in that first relationship, a child may be at a disadvantage for forming future secure attachments (Howes & Hamilton, 1993). Much research on continuity of caregiving in ECE settings has supported the claim that children require consistent and stable caregivers to form an attachment (Essa, 2006). Research has indicated children’s multiple transitions to different teachers in ECE settings may disrupt attachment (Goossens & van IJzendoorn, 1990; Howes & Hamilton, 1992, 1993; Ritchie & Howes, 2003). If only a few disruptions in caregiving are related to impaired attachment and issues with social competence, children experiencing frequent caregiver changes in institutional care may be at even greater risks for problems in social development.

Transitions between caregivers also influence children’s general development. Research within Russian BHs has indicated that children with caregivers trained to be more sensitive and responsive showed improvement in developmental quotient before and after, but not during, a transition to a new caregiver (McCall et al., 2012). This suggests that caregiver transitions may be a disruptive event for young children.

Group Size

For over a decade, child professionals have recommended that children-adult ratios in non-residential childcare settings not exceed 3:1 for infants, 4–5:1 for toddlers, and 7–8:1 for preschoolers (De Schipper, Riksen-Walraven, & Geurts, 2006). These recommendations were based on research suggesting that low ratios and small group size are related to higher quality caregiving, including sensitivity to children’s distress, positive regard, and mental stimulation (De Schipper et al., 2006; Goossens & Melhuish, 1996; NICHD Early Child Care Research Network [NICHD ECCRN], 1996, 2000). This effect was stronger at younger ages (NICHD ECCRN, 2000). Researchers theorize that caregivers must spread their attention across multiple children in group care, decreasing the individualized attention that may be crucial to meet children’s developmental needs (Ahnert, Pinquart, & Lamb, 2006; Bakermans-Kranenburg et al., 2011).

A Comprehensive Intervention in Institutional Care

In 2000, a multinational team began training caregivers as part of a large quasi-experimental study testing the effects of a comprehensive intervention implemented in BHs in St. Petersburg, Russian Federation (for details, see The St. Petersburg—USA Orphanage Research Team, 2008). The original study included three treatment groups, assigned based on the BH administration and staff willingness to implement required changes. The Training and Structural Changes (T+SC) condition provided caregivers with training on early childhood development and sensitive, responsive interactions with both typically developing children and those with a variety of disabilities. Classroom training was accompanied by supervision and technical assistance on the wards. The goal of the structural changes was to support caregiver-child relationships by creating a more family-like environment. This included creating wards of fewer children integrated by age and disability status served by fewer and more consistent caregivers. The Training Only (TO) condition included the same training as in T+SC but no structural changes, and the no intervention control group (NoI) continued care as usual. It is important to note that each of the BH directors believed that the type of care they provided in their BH was the most beneficial to the children. The previous report of the effects of the intervention revealed mean differences between children in the T+SC condition, the TO condition, and the NoI condition (The St. Petersburg—USA Orphanage Research Team, 2008).

Present Study

The present study describes a secondary analysis of data from the Russian BH intervention study to determine whether caregiver-child interaction quality, caregiver transitions, and group size mediate the effect of the intervention on children’s attachment and physical growth (The St. Petersburg—USA Orphanage Research Team, 2008). The current study addresses whether individual differences in caregiver interaction quality and specific relationship context components mediated the intervention effect. A previous analysis of this database indicated that the quality of the caregiving behavior partially mediated the relation between the intervention and children’s general behavioral development (i.e., Battelle DQs), but did not find mediating effects for stability of caregivers (Rosas et al., 2013). The present study continues efforts to break down the original intervention into some of its components and is the first to utilize a multiple mediator model to determine the combined mediation effects of interaction quality, caregiver transitions, and group size on other outcomes, specifically children’s attachment behaviors and physical growth1.

Method

Participants

The current sample, a subset of the original, includes all typically developing children who were between 11 and 19 months at the time of an attachment behaviors assessment and who had resided in one of the three BHs for at least 3 months after the interventions were completely implemented (Attachment behavior analysis: N = 163, 86 males2, Age M = 15.98 months; Growth analysis: N= 159, 88 males, Age M = 16.33 months).

Procedure

Many assessments were conducted periodically on children, and the assessments used in the current study were conducted after children had spent at least 3 months in the completed intervention condition (or 3 months in BH for NoI).

Caregiver-child interaction quality

Caregiver-child interaction quality was measured using the complete Parent-Child Early Relational Assessment (PCERA; Clark, 1985). PCERA observations occurred at intake to the BH, 3, 6, 9, 12, 18, 24, 36, 48 months, and at departure. The present study utilized the total PCERA score at the oldest age available for each child within the sampled age range (11–19 months). The PCERA includes 65 ratings of social-emotional relational dimensions on a 5-point scale, with higher scores reflecting more positive indicators.

During assessments, children were accompanied by their preferred caregiver, i.e., who knew the child best. Each observation was made in a separate room and began with the caregiver feeding the child 100 g of fruit puree and engaging the child in a structured task based on the age of the child (diapering, getting the child to use a rattle, having the child try to find a hidden block, building a tower out of blocks). This was followed by 5 minutes of free-play in which the caregiver was asked to sit with the child on a blanket and play with the child using a variety of toys provided for them. Ratings were based only on the free-play episode. There were two primary reasons for this choice. The free-play episode was thought to most accurately reflect interactions that would be seen on the wards resulting from the intervention and would offer more variability within the sample of caregivers.

Assessors rated from videotapes the sessions on 29 caregiver characteristics, including tone, affect, mood, attitude, and style of involvement; 28 child characteristics, including mood and affect, behavioral and adaptive abilities, activity level, and communication; and 8 dyadic characteristics including affective quality and mutuality. The mean score for all 65 PCERA ratings was used for analysis.

Originally, four assessors were trained in group sessions and then practiced coding videotapes until they reached 90% agreement (within ± 1 point on the 5-point scale) on three out of four consecutive assessments (The St. Petersburg—USA Orphanage Research Team, 2008). Reliability was calculated using a sample of 20 children ranging from 3 months to 5 years, a majority without any diagnosable disabilities (The St. Petersburg—USA Orphanage Research Team, 2008). When compared with an expert coder, 58% were coded identically and 95% within one point of each other. Within pairs of coders, 55% were coded identically and 95% within one point. After year 3 of the project, six additional assessors were added. Their reliability for paired codings was high, with 96% of the 65 items rated identically or within 1 point.

Caregiver transitions

Each BH kept detailed records of caregiver ward assignments, including the date each caregiver was assigned to work with a specific group of children and any ward changes, including substitutions. The number of caregiver transitions was measured by adding up the complete number of unique caregivers assigned the child’s ward during the 90 days prior to the date of outcome assessment (attachment or physical growth). Caregivers who were assigned to the ward more than once during the 90-day period were counted only once to provide the total number of different caregivers the child experienced during that period. It is important to note that at times, changes in caregivers may have been a result of children being reassigned to a different ward. This would mean that those transitions to different set of caregivers were accompanied by additional changes, including changes in peers and physical environment.

Group size

The BHs also kept similar records of child ward assignments. Group size was determined from the total of number of children assigned to the ward on the day prior to the child’s outcome assessment.

Attachment behaviors

The PCERA 5 minutes free-play episode was followed by twice repeated sequence of separation (3 minutes) and reunion (3 minutes) episodes. The camera operator acted as the “stranger” and remained in the room the entire time so that the child was never completely alone. Videos of the procedure for typically developing children 11 to 19 months of age were coded for attachment ratings by assessors on a 7-point scale for Proximity Seeking, Contact Maintaining, Avoidant Behavior, and Resistance for each reunion episode (Ainsworth, Blehar, Waters, & Wall, 1978; See The St. Petersburg—USA Orphanage Research Team, 2008 for details). Then, attachment dimensions, continuous measures of attachment, were calculated from the attachment behavior ratings according to Fraley and Spieker (2003): Proximity + Contact-Avoidance (PCA) and Resistance.

Physical growth

BH physicians measured height, weight, and head circumference at intake, 3, 6, 9, 12, 18, 24, 36, 48 months, and at departure. For infants who were not able to stand on their own, height was measured as recumbent length, by placing them on their backs with heads against a vertical edge, depressing the knees, and measuring the child’s length. Weight was assessed with counterbalanced scales, and head circumference was measured using ordinary tape measures.

Physical growth data were converted to standardized z-scores using the Center for Disease Control standardized physical growth program. This program generated standardized z-scores for each child’s measurement to allow comparison to typical home-reared (American) children at that age. For example, a z-score of −2.3 would indicate that the child was 2.3 standard deviations below the mean of a large sample of USA children at the same age.

Analysis included the last available physical growth assessment for a child within the sampled age range. In many cases, this last available measures of physical growth occurred prior to the assessment of caregiver-child interaction quality (PCERA). This violates basic causal assumptions, challenging the notion that caregiver-child interaction quality could mediate the relationship between intervention condition and growth outcomes. However, of the children whose last available physical growth data was collected before caregiver-child interaction quality, all but four had physical growth assessments completed within one month prior to the caregiver-child interaction quality assessment. In fact, many of those were completed less than a week prior to the interaction quality assessment. It is reasonable to assume children’s physical growth scores would not change drastically within a single month and therefore growth data collected prior to caregiver-child interaction quality would be an adequate proxy for growth scores after the time of caregiver-child interaction quality assessments. Analysis was completed both including and excluding those who had growth data from within one month prior to the interaction quality assessment, and indeed, there was little difference in the general mediation results. Therefore, analysis with physical growth data collected within one month prior to the interaction quality assessments is presented here.

Results

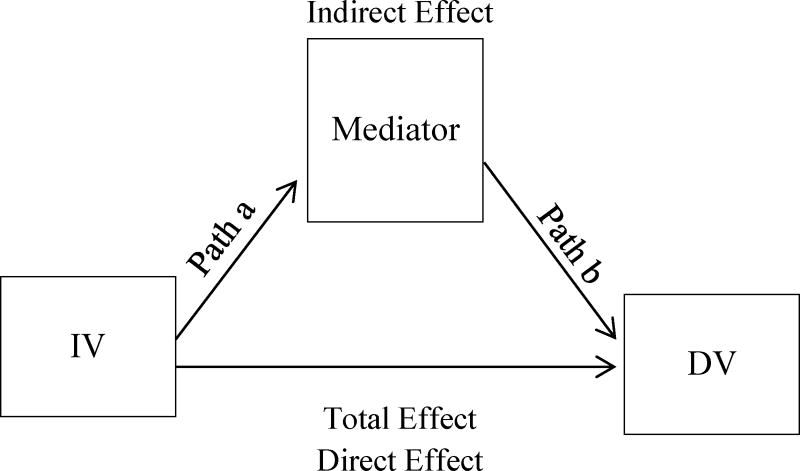

Mediation analyses were performed using the Baron and Kenny (1986) causal-steps approach (see Figure 1). This approach requires significant correlations between the independent variable and the dependent variable (total effect), the independent variable and potential mediator (path a), and the mediator and dependent variable (path b). In order for mediation to occur, the indirect effect must also be significant, indicating that the independent variable predicts the dependent variable via the tested mediator. The direct effect is the remaining prediction of the dependent variable after controlling for the mediator’s effect. For mediation to occur, this direct effect must be smaller than the total effect. Full mediation, which requires that the direct effect be zero within sampling error when controlling for the mediator, indicates that the relationship between the independent and dependent variable is fully explained by the effects of the tested mediators. Partial mediation, which is present if the direct effect remains significant after controlling for the mediator but all other conditions for mediation are met, indicates that a substantial portion of the relationship is yet to be explained.

Figure 1.

Mediator model.

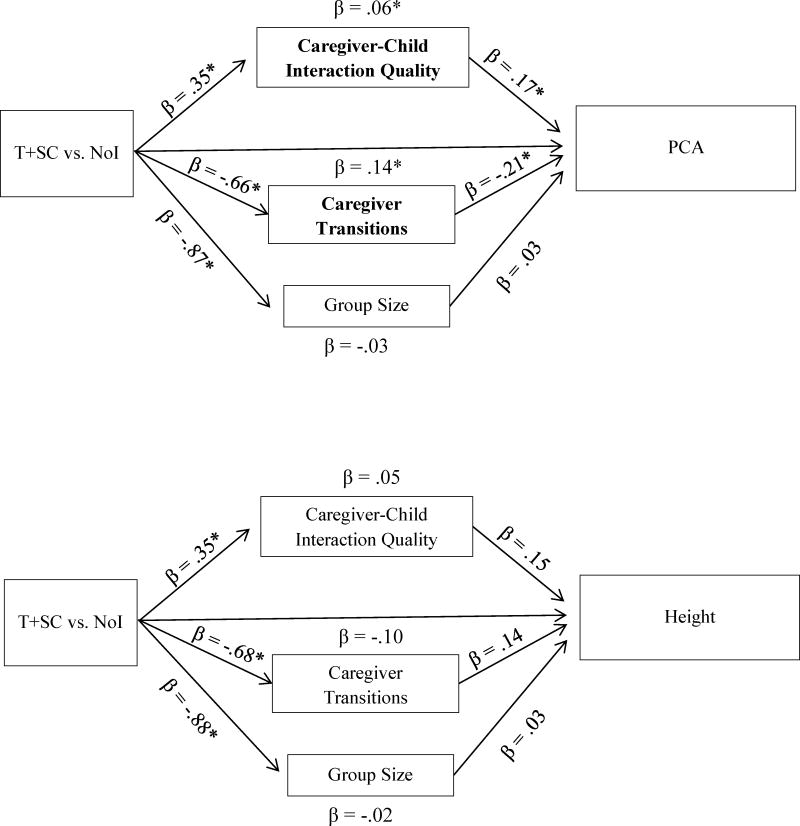

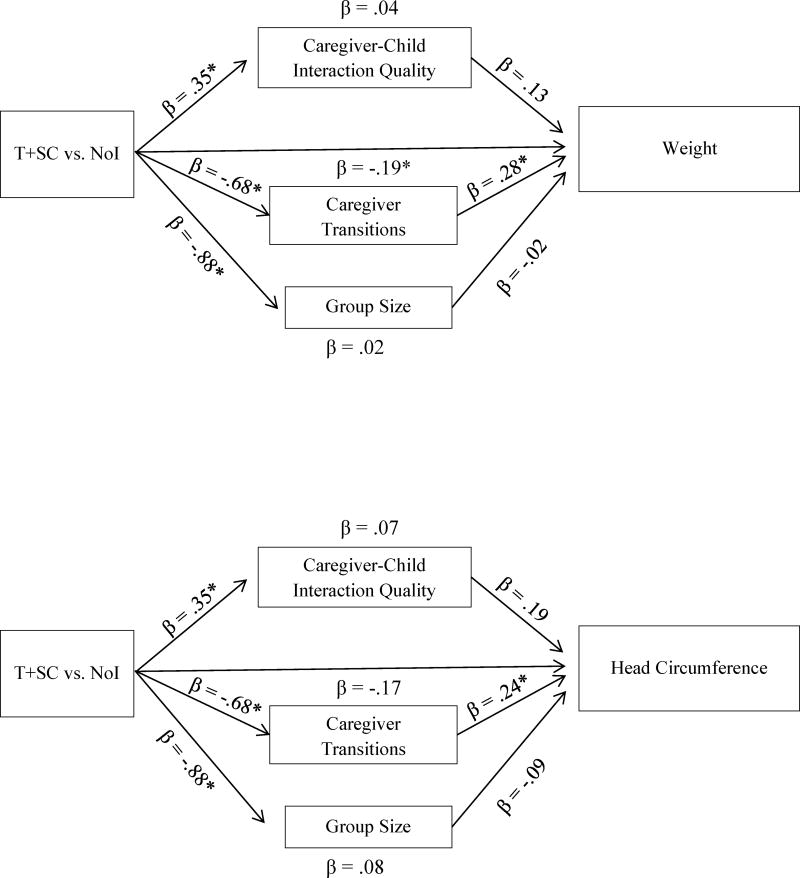

Ninety-five percent bias-corrected confidence intervals (CI) were created using bootstrapping methods with 1000 samples. For each analysis, the independent variable was the intervention group (T+SC, TO, and NoI) represented by dummy variables; potential mediators were caregiver-child interaction quality (PCERA), caregiver transitions, and group size; and age at outcome assessment and time in the intervention were includes as covariates. Mediation analyses were performed for each of the following outcome variables: Proximity + Contact – Avoidance (PCA) attachment dimension, height, weight, and head circumference. Multiple mediator models were tested for all outcome variables to estimate whether a mediator had a mediating effect above and beyond the inclusion of other mediators. Standardized coefficients and 95% CI are reported. Figures 2 and 3 portray the path diagrams corresponding to the results. Linearity of relations between mediators and dependent variables was determined by visual examination of scatterplots.

Figure 2.

Multiple mediation models for T+SC versus NoI, covarying for age and time in the intervention. Coefficients in bold represent significant mediation. Note that the total and direct effects are not pictured here. *indicates significance at p =.05.

Figure 3.

Multiple mediation models for T+SC versus NoI, covarying for age and time in the intervention. Coefficients in bold represent significant mediation. Note that the total and direct effects are not pictured here. *indicates significance at p =.05.

Attachment Behaviors

Caregiver-child interaction quality and caregiver transitions fully mediated the difference between T+SC and NoI conditions on the PCA attachment dimension (See Tables 1 & 2, Figure 2). The pathways for these two mediators met of the Baron and Kenny (1986) causal-steps criteria as follows. Specifically for caregiver-child interaction quality and caregiver transitions mediators, intervention group was associated with attachment PCA. T+SC had significantly higher attachment PCA than NoI (total effects 1 & 2)3. In addition, there were significant associations between intervention group and caregiver-child interaction quality and caregiver transitions. T+SC had significantly higher caregiver-child interaction quality and fewer caregiver transitions than NoI (paths a1 & a2). Caregiver-child interaction quality positively predicted PCA (path b1), and caregiver transitions negatively predicted PCA (path b2). Finally, the indirect effects were significant while the direct effect was not significant, indicating full mediation.

Table 1.

Multiple Mediator Analysis: Mediation Paths for T+SC versus NoI

| Caregiver-Child Interaction Quality1 | Caregiver Transitions2 | Group Size3 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||

| Path | B | 95% CI | B | 95% CI | B | 95% CI | |

| PCA | a | .35 | [.19, .51]* | −.66 | [−.79, −.53] * | −.87 | [−.97, −77]* |

| b | .17 | [.01, .32] * | −.21 | [−.38, −.03] * | .03 | [−.22, .28] | |

| indirect | .06 | [.00, .14] * | .14 | [.02, .26] * | −.03 | [−.25, .19] | |

| direct | .24 | [−.02, .51] | .24 | [−.02, .51] | .24 | [−.02, .51] | |

| total | .30 | [.04, .56] * | .37 | [.09, .66] * | .21 | [−.04, .43] | |

|

| |||||||

| Height | a | .35 | [.17, .50]* | −.68 | [−.81, −.55]* | −.88 | [−.98, −.78]* |

| b | .15 | [−.02, .31] | .14 | [−.12, .40] | .02 | [−.31, .34] | |

| indirect | .05 | [−.01, .12] | −.10 | [−.28, .08] | −.02 | [−.30, .28] | |

| direct | .54 | [.23, .85]* | .54 | [.23, .85]* | .54 | [.23, .85]* | |

| total | .59 | [.31, .87]* | .44 | [.11, .75]* | .52 | [.27, .77]* | |

|

| |||||||

| Weight | a | .35 | [.17, .50]* | −.68 | [−.81, −.55]* | −.88 | [−.98, −.78]* |

| b | .13 | [−.06, .29] | .28 | [.07, .52]* | −.02 | [−.32, .26] | |

| indirect | .04 | [−.02, .11] | −.19 | [−.38, −.04]* | .02 | [−.24, .30] | |

| direct | .46 | [.18, .74]* | .46 | [.18, .74]* | .46 | [.18, .74]* | |

| total | .50 | [.23, .77]* | .27 | [−.06, .58] | .48 | [.24, .73]* | |

|

| |||||||

| Head Circumference | a | .35 | [.17, .50]* | −.68 | [−.81, −.55]* | −.88 | [−.98, −.78]* |

| b | .19 | [−.00, .38] | .24 | [−.02, .49] | −.09 | [−.42, .24] | |

| indirect | .07 | [−.00, .15] | −.17 | [−.35, .01] | .08 | [−.21, .37] | |

| direct | .24 | [−.08, .57] | .24 | [−.08, .57] | .24 | [−.08, .57] | |

| total | .31 | [.01, .62]* | .07 | [−.28, .41] | .31 | [.07, .56]* | |

Table 2.

Mean and Standard Deviations for PCA Models

| PCA | Caregiver-Child Interaction Quality | Caregiver Transitions | Group Size | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| T+SC (n = 49) |

M = 2.74 SD = 3.01 |

M = 3.68 SD = .30 |

M = 6.92 SD = 1.01 |

M = 6.39 SD = .98 |

| NoI (n = 62) |

M = .62 SD = 2.43 |

M = 3.43 SD = .32 |

M = 10.79 SD = 3.41 |

M = 12.03 SD = 2.71 |

Group size did not mediate the difference between T+SC and NoI. No significant difference was found between the intervention conditions after adjusting for age at assessment and time in the intervention along with the other mediators (total effect 3). Although, T+SC had significantly lower group size than NoI (path a3), the mediator did not significantly predict the PCA dimension under the same conditions (path b3).

Growth

Height

No mediation was found for height (Tables 1 & 3, Figure 2). Intervention group was associated with Height. Height z-scores were significantly higher in T+SC than in NoI (total effects 1, 2, & 3). Intervention group was also associated with caregiver-child interaction quality, caregiver transitions, and group size. T+SC had significantly higher caregiver-child interaction quality, significantly fewer caregiver transitions, and significantly lower group size than NoI (paths a1, a2, & a3). Each of these associations confirm the effect of the intervention. However, the mediators failed to significantly predict the height (paths b1, b2, & b3).

Table 3.

Means and Standard Deviations for Physical Growth Models

| Height z-score | Weight z-score | Head Circ. z-score | Caregiver-Child Interaction Quality | Caregiver Transitions | Group Size | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T+SC (n = 52) |

M = −.78 SD = .94 |

M = −1.35 SD = 1.20 |

M = −.67 SD = 1.22 |

M = 3.72 SD = .34 |

M = 6.90 SD = .98 |

M = 6.40 SD = .98 |

| NoI (n = 59) |

M = −1.82 SD = 1.07 |

M = −2.25 SD = 1.37 |

M = −1.25 SD = 1.36 |

M = 3.43 SD = .33 |

M = 10.97 SD = 3.39 |

M = 12.19 SD = 2.64 |

Weight

No mediation was found for weight (Tables 1 & 3, Figure 3). Violations of the Baron and Kenny (1986) causal-steps requirements varied by the mediator tested.

For caregiver-child interaction quality and caregiver transitions, weight z-scores were significantly higher in T+SC than in NoI (total effects 1 & 3). Intervention group was not associated with caregiver-child interaction quality or group size after adjusting for age at assessment and time in the intervention along with the other mediators (paths a1 & a3), nor were these mediators associated with weight (paths b1 & b3).

There was no significant total effect for caregiver transitions after adjusting for age at assessment and time in the intervention along with the other mediators (total effect 2). However, T+SC had significantly fewer caregiver transitions than NoI (path a2), and caregiver transitions positively predicted weight (path b2).

Head circumference

No significant mediation was found for head circumference (Tables 1 & 3, Figure 3). Intervention group was associated with head circumference for two of the potential mediators. For caregiver-child interaction quality and group size, T+SC had significantly greater head circumference z-scores than NoI (total effects 1 & 3). For caregiver transitions there was no total effect, after adjusting for age at assessment and time in the intervention along with the other mediators (total effect 2). Intervention group was associated with caregiver-child interaction quality, caregiver transitions, and group size. T+SC had significantly higher caregiver-child interaction quality, significantly fewer caregiver transitions, and significantly smaller group size than NoI (paths a1, a2, & a3). These differences were the expected results of the intervention. However, the mediators did not significantly predict head circumference (paths b1, b2, & b3).

Although the effects were not significant, some of the effects neared significance and are worth noting. The positive prediction of caregiver-child interaction quality on intervention group neared significance (path b1), as did the indirect effect of intervention group on head circumference through caregiver-child interaction quality (indirect effect 1). Together with the lack of a significant direct effect, this indicates that the analysis neared detecting full mediation via caregiver-child interaction quality.

Discussion

It was hypothesized that the quality of interactions between caregivers and children and the relationship context in which those interactions occurs mediate the association between the intervention condition and attachment and physical growth outcomes. Results partially supported this hypothesis for attachment, but failed to support the hypothesis for physical growth outcomes.

Attachment Behaviors

Results indicated that both caregiver-child interaction quality and caregiver transitions fully mediated the association between treatment condition and the PCA attachment dimension. According to multiple regression, caregiver-child interaction quality’s mediating effect uniquely accounted for 2.15% of the variance in attachment behaviors. This suggests that improvements in interaction quality can lead to improvements in attachment behaviors, regardless of the surrounding relationship context, at least as operationalized here. This is in accordance with past theory and research, demonstrating quality interactions with high sensitivity and responsiveness from caregivers encourages the growth of attachment (Ainsworth, 1979; Bakermans-Kranenburg et al., 2003; Brumariu & Kerns, 2010).

Number of caregiver transitions also mediated the association between intervention condition and the PCA attachment dimensions, uniquely accounting for 1.68% of the variance in attachment. This also suggests that the consistency of caregivers is an important factor in the development of attachment relationships. The full mediation model accounted for 18.75% of the variance in PCA attachment. Within that, 11.31% of the variation accounted for came from overlap between variables. This further supports the theory that relationship context and other characteristics matter to the development of attachment relationships.

Physical Growth

Contrary to the hypotheses, neither caregiver-child interaction quality, caregiver transitions, nor group size significantly mediated the association between intervention group and height, weight, or head circumference. However, children in T+SC did have significantly greater height, weight, and head circumference z-scores than children in NoI, indicating that the intervention was related to improvements in these growth outcomes within this subsample. According to multiple regression, intervention group and the child age covariate seemed to have stronger influences within the physical growth models (uniquely accounting for 6.84% & 3.03% of the variance respectively for height, 8.98% & 2.88% for weight, and 1.24% & 1.80% for head circumference). Yet, the unique contributions of caregiver-child interaction quality and caregiver transitions were comparable to those in the attachment behaviors model (2.20% & 0.59% for height, 1.47% & 2.80% for weight, and 3.46% & 2.06% for head circumference).

The overall lack of mediation for physical growth is not readily explained. However, there are many other underlying biological factors which may uniquely and interactively influence children’s physical development that are simply not accounted for in this study. Extant research suggests that children with greater growth impairment prior to intervention experience greater catch-up, and degree of growth impairment at the beginning of the intervention was not taken into consideration within the present analyses (D. Johnson, personal communication, March 19, 2016). Other aspects of the environment may also account for these differences in growth scores, such as environment quality as measured by the HOME scale (Rosas et al., 2013).

Primary Importance of Caregiver-Child Interaction Quality

It was expected that caregiver-child interaction quality would be a main mediating factor for each type of outcome. The relationship context variables of caregiver transitions and group size were thought to support the effects of interaction quality. However, since they were directly manipulated by the intervention, they could also act as individual mediators.

In accord with hypotheses, caregiver-child interaction quality was a significant mediator for attachment behaviors (PCA) and neared significance as a mediator for head circumference. This suggests that improvement in the quality of interactions between caregivers and children as a result of the intervention received in T+SC was crucial to the improvement of some attachment behaviors and physical growth outcomes. In addition, evidence from the PCA mediation model suggests that number of caregiver transitions provides some support to strengthen effects on attachment. Few caregiver transitions theoretically may allow each individual child to spend greater time developing relationships with specific caregivers, furthering the effects of improvements in quality of caregiver-child interaction.

Limitations

The present study is limited by a number of factors. First, its quasi-experimental design may have influenced the results and may limit generalizability. Although each BH administrator believed that the intervention (or maintenance of the traditional style of care in NoI) received at their BH was best for the children, possible confounding differences in BH care, such differences in caregiver education or experience or physical environment and care, cannot be ruled out. In addition, the quasi-experimental design places limits on the assumption of causality. Mediation analysis helps to tease apart the importance of various variables that the intervention aimed to improve, but the analysis is still correlational in nature and cannot measure up to the evidence provided by a true experiment.

As mentioned previously, caregiver transitions is somewhat confounded by children changing wards and therefore experiencing a number of transitions beyond that of switching caregivers. The current analyses do not control for these additional changes in children’s lives and therefore, results should be interpreted with caution.

The small age range of the present sample also limits the ability to see long-term outcomes. It would be preferable to track changes in attachment behavior and physical growth longer into childhood to determine if the effects of the intervention are lasting or whether there is a lag between intervention and improvement.

The lack of mediation from group size raises the question of whether children-adult ratio is more salient to children’s development than the number of children within a group. Research from American early care and education settings suggests that the effects of the two variables are similar (NICHD ECCRN, 1996; Goossens & Melhuish, 1996; De Schipper et al., 2006). However, both group size and ratio are highly regulated within these ECE settings. Therefore, limited variability may mask the true effects. Unfortunately, the present data set did not lend itself to easy identification of children-adult ratio, which would have been preferable.

Results provided little insight into how caregiver-child interactions and relationship context characteristics influence children’s physical growth. More study with careful consideration of environmental characteristics (including nutrition and medical care) is needed to further tease apart the influences of these variables on physical growth. Future research would also benefit from measures of cortisol or other stress hormones to further confirm the psychosocial short stature hypothesis.

Finally, the present intervention study was conducted in government sponsored Russian BHs. The intervention effects may not be generalizable to institutionalized care in other nations, cultures, or privately operated institutions.

Conclusions

Despite providing limited insight into children’s physical growth, the present study has clearer implications regarding attachment behaviors. The results of the study suggest that the quality of interactions between children and their caregivers in institutional settings is vitally important for the children’s attachment behaviors. Interaction quality was a key mediating factor in this study, suggesting that improving interaction quality should be a primary target of interventions within institutional settings. The training model utilized in this study was, in fact, successful in raising the quality of caregiver-child interactions. The model used a train-the-trainer model with close supervision and technical assistance provided on the ward. Similar interventions emphasizing caregiver-child interactions implemented by others in Latin American institutions and institutions of Russian Federation have also produced improvements in children’s development (Groark et al., 2013a, 2013b; McCall et al., 2010; Muhamedrahimov et al., 2009).

The mediation of caregiver transitions also indicated the importance of stability of caregivers to attachment. Changes in caregivers may be enough to disrupt general attachment development (Goossens & van IJzendoorn, 1990; Howes & Hamilton, 1992, 1993; Ritchie & Howes, 2003), but it is also likely that frequent caregiver changes simply prevents children from having enough time with specific caregivers to develop attachment relationships with those caregivers.

Results of this study suggest that to best support children’s attachment, institutions should make efforts to provide caregivers who are sensitive, responsive, and contingent in interactions with children and to ensure with consistency in whom is providing children’s direct care.

Acknowledgments

This research was funded in part by HD 050212 to authors McCall and Groark from the Eunice Shriver Kennedy National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. The interpretations and opinions expressed are those of the authors, not the funder.

The data analyzed for this article came from a research study approved by University of Pittsburgh’s Institutional Review Board (IRB# 0610059) and by the human subjects ethics committee at St. Petersburg State University in St. Petersburg, Russian Federation.

The authors would like to dedicate this article in memory of Dr. Kevin H. Kim, whose dedication to his students and colleagues made works like this possible. The authors would also like to express their thanks to Dr. Dana Johnson for his feedback regarding physical growth outcomes and their interpretation.

Footnotes

Results from the TO condition are not presented in the current report because a supplementary nutrition program was introduced within the BH that potentially biased children’s physical growth results and there was no mediation found for attachment when comparing TO to NoI.

Gender of four children with attachment data was missing from records

Subscript numbers are provided here to identify specific mediators tested: subscript 1 = caregiver-child interaction quality, subscript 2 = caregiver transitions, subscript 3 = group size. These same subscript numbers are within the column labels of Table 1.

Contributor Information

Hilary A. Warner, University of Pittsburgh

Robert B. McCall, University of Pittsburgh

Christina J. Groark, University of Pittsburgh

Kevin H. Kim, University of Pittsburgh

Rifkat J. Muhamedrahimov, St. Petersburg State University

Oleg I. Palmov, St. Petersburg State University

Natalia V. Nikiforova, Baby Home 13, St. Petersburg, RF

References

- Ahnert L, Pinquart M, Lamb ME. Security of children’s relationships with nonparental care providers: A meta-analysis. Child Development. 2006;74(3):664–679. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2006.00896.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ainsworth MDS. Infant-mother attachment. American Psychologist. 1979;34(10):932–937. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.34.10.932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ainsworth MDS, Blehar MC, Waters E, Wall S. Patterns of attachment: A psychological study of the strange situation. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum Associates; 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Bakermans-Kranenburg MJ, Steele H, Zeanah CH, Muhamedrahimov RJ, Vorria P, Dobrova-Krol NA, Gunnar MR. Attachment and emotional development in institutional care: Characteristics and catch up. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development. 2011;76:62–91. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-5834.2011.00628.x. Serial No. 301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bakermans-Kranenburg MJ, van IJzendoorn MH, Juffer F. Less is more: Meta-Analyses of sensitivity and attachment interventions in early childhood. Psychological Bulletin. 2003;129(2):195–215. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.129.2.195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baron RM, Kenny DA. The moderator–mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1986;51(6):1173. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.51.6.1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowlby J. Attachment and loss: Attachment. Vol. 1. New York, NY: Basic Books; 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Brumariu L, Kerns K. Parent-child attachment in early and middle childhood. In: Smith P, Hart C, editors. Wiley-Blackwell Handbook of Childhood Social Development. 2nd. Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell; 2010. pp. 319–336. [Google Scholar]

- Clark R. The parent-child early relational assessment instrument and manual. Madison, WI: Department of Psychiatry, University of Wisconsin Medical School; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- De Schipper EJ, Rikens-Walraven JM, Geurts SAE. Effects of child-caregiver ratio on the interactions between caregivers and children in child-care centers: An experimental study. Child Development. 2006;77(4):861–874. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2006.00907.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobrova-Krol NA, van IJzendoorn MH, Bakermans-Kranenburg MJ, Cyr C, Juffer F. Physical growth delays and stress dysregulation in stunted and non-stunted Ukrainian institution-reared children. Infant Behavior & Development. 2008;31:539–553. doi: 10.1016/j.infbeh.2008.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobrova-Krol NA, Bakermans-Kranenburg MJ, Van IJzendoorn MH, Juffer F. The importance of quality of care: Effects of perinatal HIV infection and early institutional rearing on preschoolers’ attachment and indiscriminate friendliness. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2010;51(12):1368–1376. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2010.02243.x. https//doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.2010.02243.x/full. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engle PL, Black MM, Behrman JR, Cabral de Mello M, Gertler PJ, Kapiriri L, the International Child Development Steering Group Strategies to avoid the loss of developmental potential in more than 200 million children in the developing world. Lancet. 2007;369:229–242. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60112-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Essa EL, Favre K, Thweatt G, Waugh S. Continuity of care for infants and toddlers. Early Child Development and Care. 2006;148(1):11–19. doi: 10.1080/0300443991480102. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fraley RC, Spieker SJ. Are infant attachment patterns continuously or categorically distributed? A taxometric analysis of strange situation behavior. Developmental Psychology. 2003;39(3):387–404. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.39.3.387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goossens F, Melhuish EC. On the ecological validity of measuring the sensitivity of professional caregivers: The laboratory versus the nursery. European Journal of Psychology of Education. 1996;11(2):169–176. doi: 10.1007/BF03172722. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Goossens FA, van IJzendoorn MH. Quality of infants’ attachments to professional caregivers: Relation to infant-parent attachment and day-care characteristics. Child Development. 1990;61:832–837. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1990.tb02825.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grantham-McGregor S, Cheung YB, Cueto S, Glewwe P, Richter L, Strupp B, the International Child Development Steering Group Developmental potential in the first 5 years for children in developing countries. Lancet. 2007;369:60–70. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60032-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groark CJ, McCall RB, Fish L, McCarthy SK, Eichner JC, Gee AD. Structure, caregiver-child interactions, and children’s general physical and behavioral development in three Central American institutions. International Perspectives in Psychology: Research, Practice, Consultation. 2013a;2(3):207–224. doi: 10.1037/ipp0000007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Groark CJ, McCall RB, McCarthy SK, Eichner JC, Warner HA, Salaway J, Lopez ME. The effects of a social-emotional intervention on caregivers and children with disabilities in two Central American institutions. Infants and Young Children. 2013b;26:286–305. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/IYC.0b013e3182a682cb. [Google Scholar]

- Gunnar MR. Effects of early deprivation. In: Nelson CA, Luciana M, editors. Handbook of developmental cognitive neuroscience. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press; 2001. pp. 617–629. Retrieved from http://cognet.mit.edu/library/erefs/nelson/n39/abstract.html. [Google Scholar]

- Howes C, Hamilton CE. Children’s relationships with child care teachers: stability and concordance with parental attachments. Child Development. 1992;63(4):867–878. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.ep9301120082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howes C, Hamilton CE. The changing experience of child care: Changes in teachers and in teacher-child relationships and children’s social competence with peers. Early Childhood Research Quarterly. 1993;8:15–32. doi: 10.1016/S0885-2006(05)80096-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson DE, Gunnar MR. Growth failure in institutionalized children. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development. 2011;76:92–126. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-5834.2011.00629.x. Serial No. 301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson DE, Guthrie D, Smyke AT, Koga SF, Fox NA, Zeanah CH, Nelson CA. Growth and associations between auxology, caregiving environment, and cognition in socially deprived Romanian children randomized to foster vs ongoing institutional care. Archives of Pediatric and Adolescent Medicine. 2010;164(6):507–516. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2010.56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCall RB. Research, practice, and policy perspectives on issues of children without permanent parental care. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development. 2011;76:223–272. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-5834.2011.00634.x. Serial No. 301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCall RB, Fish LA, Groark CJ, Muhamedrahimov RJ, Palmov O, Nikiforova NV. The role of transitions to new age groups in the development of institutionalized children. Infant Mental Health Journal. 2012;33(4):421–429. doi: 10.1002/imhj.21329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCall RB, Groark CJ, Fish LA, Harkins D, Serrano G, Gordon K. A socioemotional intervention in a Latin American orphanage. Infant Mental Health Journal. 2010;31(5):521–542. doi: 10.1002/imhj.20270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muhamedrahimov RJ. New attitudes: Infant care facilities in St. Petersburg, Russia. In: Osofsky JD, Fitzgerald HE, editors. WAIMH handbook of infant mental health. Vol. 1. New York: Wiley; 1999. pp. 245–294. [Google Scholar]

- Muhamedrahimov RJ, Palmov OI, Konkova MY, Shevchuk EA. Reorganization of social-emotional environment and implementation of early intervention program in baby homes of Krasnoyarsk region. Krasnoyarsk, RF: Polis; 2009. p. 64. (Мухамедрахимов, Р. Ж., Пальмов, О. И., Конькова, М. Ю., & Шевчук, Е. А. (2009). Опыт изменения социального окружения детей в домах ребенка. Внедрение технологии раннего вмешательства в домах ребенка Красноярского края. Красноярск, РФ: Полис. 64 c.) [Google Scholar]

- NICHD Early Child Care Research Network. Characteristics of infant child care: Factors contributing to positive caregiving. Early Childhood Research Quarterly. 1996;11:269–306. doi: 10.1016/S0885-2006(96)90009-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- NICHD Early Child Care Research Network. Characteristics and quality of child care for toddlers and preschoolers. Applied Developmental Science. 2000;4(3):116–135. doi: 10.1207/S1532480XADS0403_2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rosas J, McCall RB. Characteristics of institutions, interventions, and children’s development. Pittsburgh, PA: University of Pittsburgh Office of Child Development; 2011. Unpublished Manuscript. [Google Scholar]

- Rosas JM, McCall RB, Groark CJ, Muhamedrahimov R, Palmov O, Nikiforova N. Environmental quality as mediator between an institutional intervention and children’s developmental outcomes. Pittsburgh, PA: University of Pittsburgh Office of Child Development; 2013. Unpublished manuscript. [Google Scholar]

- Ritchie S, Howes C. Program practices, caregiver stability, and child-caregiver relationships. Applied Developmental Psychology. 2003;24:497–516. doi: 10.1016/S0193-3973(03)00028-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Smyke AT, Koga SF, Johnson DE, Fox NA, Marshall PJ, Nelson CA, the BEIP Core Group The caregiving context in institution-reared and family-reared infants and toddlers in Romania. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2007;48(2):210–218. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2006.01694.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talbot NB, Sobel EH, Burk BS, Lindemann E, Kaufman SB. Dwarfism in healthy children: its possible relation to emotional, nutritional and endocrine disturbances. The New England Journal of Medicine. 1947;236(21):783–789. doi: 10.1056/NEJM194705222362102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The St. Petersburg-USA Orphanage Research Team. Characteristics of children, caregivers, and orphanages for young children in St. Petersburg, Russian Federation. Applied Developmental Psychology. 2005;26:477–506. doi: 10.1016/j.appdev.2005.06.002.. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- The St. Petersburg-USA Orphanage Research Team. The effects of early social-emotional and relationship experience on the development of young orphanage children. Monographs of the Society of Research in Child Development. 2008;73:1–297. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-5834.2008.00483.x. Serial No. 291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tirella LG, Chan W, Cermak SA, Litvinova A, Salas KC, Miller LC. Time use in Russian baby homes. Child: care, health and development. 2008;34(1):77–86. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2214.2007.00766.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- UNICEF. Progress for children: A report card on child protection, No 8. New York: Author; 2009. Retrieved from http://www.unicef.org/publications/files/Progress_for_Children-No.8_EN_081309.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- van IJzendoorn MH, Bakermans-Kranenburg MJ, Juffer M. Plasticity of growth in height, weight, and head circumference: Meta-analytic evidence of massive catch-up after international adoption. Journal of Developmental & Behavioral Pediatrics. 2007;28(4):334–343. doi: 10.1097/DBP.0b013e31811320aa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van IJzendoorn MH, Palacios J, Sonuga-Barke EJS, Gunnar MR, Vorria P, McCall RB, Juffer F. Children in institutional care: Delayed development and resilience. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development. 2011;76:8–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-5834.2011.00626.x. Serial No. 301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vorria P, Papaligoura Z, Dunn J, Van IJzendoorn MH, Steele H, Kontopoulou A, Sarafidou Y. Early experiences and attachment relationships of Greek infants raised in residential group care. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2003;44(8):1208–1220. doi: 10.1111/1469-7610.00202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker SP, Wachs TD, Meeks Gardner J, Lozoff B, Wasserman GA, Pollitt E, the International Child Development Steering Group Child development: Risk factors for adverse outcomes in developing countries. Lancet. 2007;369:145–157. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60076-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Widdowson EM. Mental contentment and physical growth. Lancet. 1951;1:1316–1318. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(51)91795-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeanah CH, Smyke AT, Koga SF, Carlson E. Attachment in institutionalized and community children in Romania. Child Development. 2005;76(5):1015–1028. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2005.00894.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]