Abstract

Objective

Factors predictive of research career interest among pediatric emergency medicine (PEM) fellows are not known. We sought to determine prevalence and determinants of interest in research careers among PEM fellows.

Methods

We performed an electronically distributed national survey of current PEM fellows. We assessed demographics, barriers to successful research, and beliefs about research using 4-point ordinal scales. The primary outcome was the fellow-reported predicted percentage of time devoted to clinical research five years after graduation. We measured the association between barriers and beliefs and the predicted future clinical research time using the Spearman correlation coefficient.

Results

Of 458 current fellows, 231 (50.4%) submitted complete responses to the survey. The median predicted future clinical research time was 10% (interquartile range 5–20%). We identified no association between gender, residency type, nor prior research exposure and predicted future research time. The barrier most correlated with decreased predicted clinical research time was difficulty designing a feasible fellowship research project [Spearman coefficient (ρ) 0.20, p=0.002]. The belief most correlated with increased predicted clinical research time was excitement about research (ρ=0.69, p<0.001).

Conclusions

Most fellows expect to devote a minority of their career to clinical research. Excitement about research was strongly correlated with career research interest.

Introduction

Research in pediatric emergency medicine (PEM) is crucial to advancing care for children.1 Unmet areas of need in pediatric emergency medicine investigation include airway management, respiratory disease, and trauma; and emergency care system topics such as out-of-hospital management, knowledge deterioration, and patient outcomes.2 Advancing science in these domains of pediatric emergency medicine has the potential to reduce the burden of childhood disease.1,2 Thus, attracting greater numbers of new investigators with a diversity of interests could more quickly advance these important areas of investigation.

Currently, all PEM fellows are required to participate in a scholarly activity during their training. Scholarly pursuits including clinical research, bench research, quality improvement, medical education, advocacy, and public policy are vital to improving the emergency care of children and may fulfill the scholarly requirement. However, this requirement is most often fulfilled through completion of a clinical research investigation.3 Toward that requirement, the American Board of Pediatrics (ABP) mandates a curriculum including biostatistics, bioethics, study design, and research methods; development of research skills is an essential part of PEM fellowship. Nonetheless, despite its importance, few recent PEM fellowship graduates pursue research careers.4 Presently, 13% of graduating PEM fellows plan to pursue a career with a major research component, the lowest among all pediatric subspecialties.5 Several barriers exist to the pursuit of a PEM research career: there are few funded research mentors in emergency medicine to inspire the next generation of dedicated researchers, academic PEM physicians often feel underprepared for research careers after completing fellowship, and a large resource investment is required to grow a PEM research career.6–9 Without salary support and research funding, obtaining substantial protected time for research is difficult, as PEM physician salaries are often tied to clinical revenue.10

The factors that predict interest in clinical research for PEM trained physicians are not known. The objective of this study was to determine the prevalence and determinants of planned involvement in PEM clinical research after fellowship graduation.

Materials and Methods

Study design

This was a cross-sectional study of current PEM fellows. The Institutional Review Board exempted this study from review.

Study Participants

Participants were eligible if they were current PEM fellows in an American Council for Graduate Medical Education-accredited fellowship. Responses were excluded if they were incomplete. We estimated the number of eligible participants a priori as the 458 individuals matched to PEM fellowships in 2013–2015 based on National Residency Matching Program (NRMP) data.11

Survey Development and Measurements

The survey instrument was developed by the study investigators and reviewed by the Pediatric Emergency Medicine Collaborative Research Committee (PEM CRC) survey committee. Items were generated by an author (KAM) to assess prior research experience, current research experience, perceived barriers and beliefs regarding research in fellowship, and potential future career involvement in research. The initial 26-item survey went through three rounds of item reduction and revision. The survey was then assessed for content validity by additional PEM experts (RDM and LEN) who reviewed and provided feedback. The survey order and wording were modified accordingly, and additional items were added to better assess research beliefs and barriers. The survey was pilot tested with a PEM fellow and a recent PEM fellowship graduate for functionality and modified to increase understandability. The final survey consisted of 33 items and took 10 minutes based on pilot testing (Appendix).

Survey Distribution

The survey was distributed using an electronic web-link via REDCap (Research Electronic Data Capture).12 Participants were contacted via two methods specifically directed towards PEM fellows. First, all PEM fellowship directors were contacted via the PEM Fellowship Directors Listserv, managed by a co-investigator (CMM). Fellowship directors were instructed to forward the web-link to current PEM fellows. The survey was distributed using the listserv three times over three months.13 In addition, the survey link was also provided to attendees of the annual National PEM Fellows’ Conference which hosts current PEM fellows (conference held in March 2016 in Ann Arbor, MI). The survey was open between January and March 2016. Consent was implied by completion of the survey, and all responses were anonymous.

Survey Items and Measurements

We elicited demographics characteristics about each participant’s research background and current or former PEM fellowship. States were categorized into regions using United States Census tract categories (Northeast, Midwest, South, and West).14 Participants were asked whether their fellowship research received no funding, funding from inside the institution only, or funding from outside the institution.

Participants answered questions about specific barriers to research using a 4-point ordinal scale including “not a barrier,” “could overcome with a little effort,” “could overcome with a great deal of effort,” or “could not overcome.” We defined a significant barrier as one that required a great deal of effort to overcome or could not be overcome. Participants rated beliefs about research using a 4-point ordinal scale of “strongly disagree,” “disagree,” “agree,” or “strongly agree.” Responses were dichotomized as agree (either agree or strongly agree) or disagree (disagree or strongly disagree).

Outcomes

Each participant estimated the percentage time (0–100) he or she plans to devote five years after starting as PEM faculty to each of the following: patient care, clinical research, basic science research, administration, education, or other pursuits. We defined research as “any activity with the goal of generating generalizable knowledge, and can include hypothesis-driven studies, quality improvement with the intent to disseminate findings (‘quality improvement research’), and education research.” Participants who replied that clinical research would be part of their career were asked at what point in training they had decided to pursue research.

The primary outcome was predicted clinical research time. We dichotomized predicted clinical research time as follows: clinical research career if predicted clinical research time were ≥ 20% of anticipated professional time and no clinical research career if < 20%.

Data Analysis

Categorical variables were reported using frequencies, and continuous variables using medians [interquartile ranges (IQR)]. The Fisher exact test was used to compare categorical data. Wilcoxon rank-sum and Kruskal-Wallis tests were used to compare continuous data. Correlations between continuous responses and predicted clinical research time were performed using a Spearman rho (ρ). We considered results significant at the level p < 0.05. Because we performed 10 tests of correlation for barriers and beliefs with predicted clinical research time, we recomputed p values after adjustment for multiple comparisons using the Holm method.15 Data were analyzed using R version 3.2.3 (R Foundation, Vienna, Austria) and ggplot2.16

Results

Of the 458 eligible PEM fellows, 257 (56.1%) responded. Twenty-six responses were incomplete; therefore, we analyzed 231 complete responses (overall response rate 50.4%). Characteristics of the study population are presented in Table 1. The geographic distribution, gender and fellowship year were similar to available national data for PEM fellow trainees.4,11

Table 1.

Demographics and research experience of current pediatric emergency medicine fellows.

| Participants (N = 231) n (%) |

|

|---|---|

| Fellowship Year | |

| Year 1 | 78 (34) |

| Year 2 | 81 (35) |

| Year 3 | 70 (30) |

| Year 4 or later | 2 (1) |

| Female gender | 145 (63) |

| Region | |

| Northeast | 66 (29) |

| Midwest | 59 (26) |

| South | 66 (29) |

| West | 28 (12) |

| Residency* | |

| General emergency medicine | 18 (8) |

| Pediatrics | 215 (93) |

| Advanced degrees other than MD | |

| MPH | 15 (7) |

| MS | 17 (7) |

| PhD | 1 (0) |

| Other | 10 (4) |

| Research experience before fellowship | 203 (88) |

| Previous research experience | |

| Basic science | 93 (40) |

| Clinical | 184 (80) |

| Qualitative | 72 (31) |

| Translational | 22 (10) |

| Any presentation experience | 181 (78) |

| Poster presentation | 148 (64) |

| Platform presentation | 67 (29) |

| Published paper | 117 (51) |

Totals may not add to 100% due to missing data.

Two participants trained in both general emergency medicine and pediatrics.

Research Involvement

The majority of respondents (203; 87.9%) had research experience prior to fellowship and 106 (45.9%) had time free from clinical duty during residency to conduct research, such as a brief research rotation or extended clinical leave to conduct research. Those with pre-fellowship research time free from clinical duty predicted a higher median percentage of time devoted to clinical research than those without (10%, IQR 5–25 versus 10%, IQR 0–15; p=0.006).

One hundred sixty-four (71.0%) respondents reported currently serving as the lead investigator on a research project at their home institutions, 17 (7.4%) reported collaborative involvement in a project led by other investigators, and 29 (12.6%) reported both. Participation in multi-institutional research was uncommon, with 25 (10.8%) involved in a current multi-center study, and 11 (4.8%) leading such projects. Twelve (5%) current fellows reported being uninvolved in research. Eleven (4.8%) survey participants had extramural funding for fellowship research, 58 (25.1%) had internal funding only, and 159 (68.8%) had no funding. Respondents with extramural funding planned to devote a higher percentage of time to research than those with internal funding only or no funding: extramural funding [median 20%, IQR 18–33%] vs. internal funding (10%, IQR 6–20%; p = 0.02) and vs. no funding (10%, IQR 0–20%; p=0.003).

Career Plans

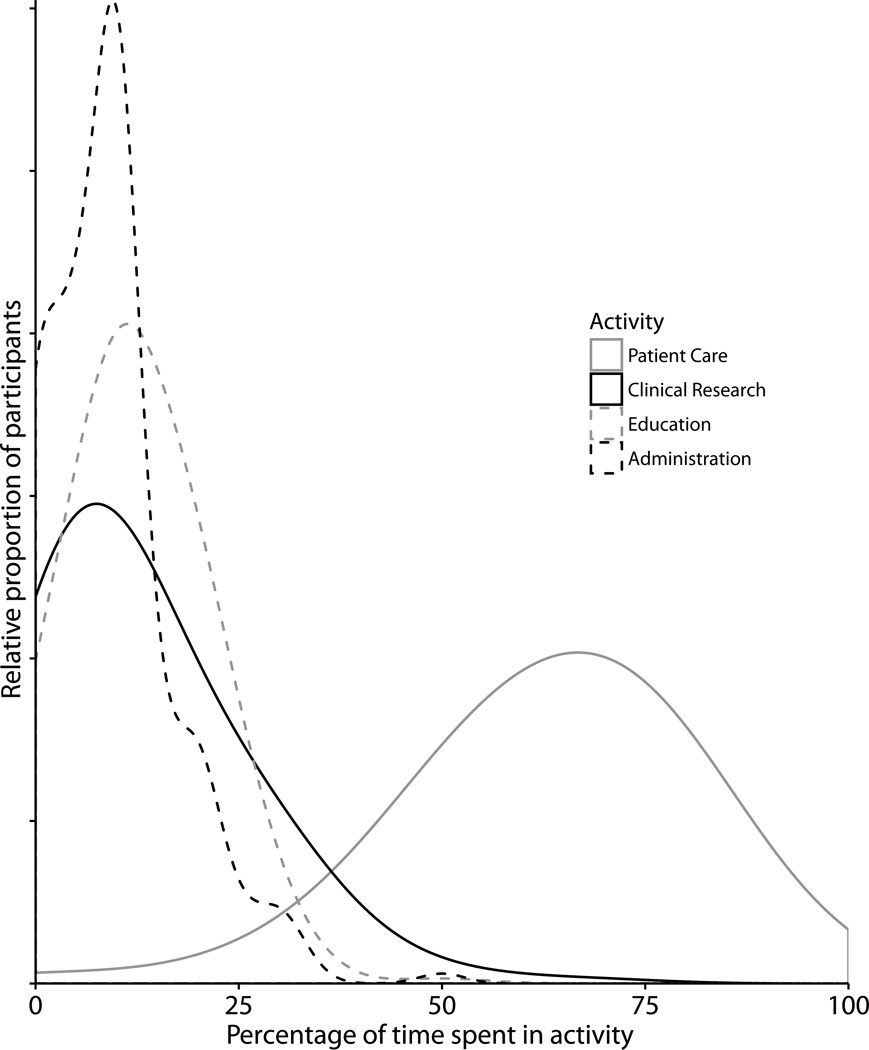

Five years after completing fellowship, respondents planned to spend a median 65% [IQR 50–75] of their working time devoted to patient care, 10% (IQR 5–20) to clinical research, 10% (IQR 10–20) to education, and 10% (IQR 5–10) to administration (Figure). Six (2.6%) participants planned time devoted to basic science research. Five participants said they anticipated “other” pursuits: two planned advocacy or community outreach, two planned global health, and one each planned clinical bioethics, education research, and sports medicine.

Figure 1.

Smoothed histogram of predicted time devoted to specific professional activities. The height of the curve represents the relative proportion of participants who plan a professional activity, e.g. the most common prediction for clinical research time was 10%, and very few predicted more than 50% of time spent on clinical research activities. The area under each curve sums to one. Basic science research and other activities were omitted because the median time anticipated in each was 0%.

Among the 69 (29.9%) respondents planning to devote at least 20% of their future career to clinical research, 40 (58%) made that decision in residency or prior, 17 (25%) in the first fellowship year, 8 (12%) in the second fellowship year, and 4 (6%) in the third fellowship year. None of the following factors was associated with predicted clinical research time in 5 years: gender (p=1.00), pediatrics vs. general emergency medicine residency (p=0.32), presence or absence of prior research experience (p=0.19), or current year in fellowship (p=0.18).

Barriers to Research

Approximately half of respondents (109; 47.2%) reported at least one significant barrier to fellowship research (Table 2). The most common barrier cited was having time to do research (63; 27.4%). The barriers significantly correlated with predicted future clinical research time were designing a feasible research project (ρ=0.20, p=0.002) and identifying an interesting research question (ρ=0.18, 0.006).

Table 2.

Barriers to research, beliefs about research, and predicted clinical research time.

| Difficulty overcoming barrier | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| None | Little | Great deal | Could not overcome | ||||||

| Barrier | ρ* | n (%) | Research % | n (%) | Research % | n (%) | Research % | n (%) | Research % |

| Designing a feasible project | +0.20‡ | 41 (18) | 15 (5–25) | 130 (57) | 10 (5–20) | 56 (24) | 5 (0–15) | 2 (1) | 2† |

| Identifying interesting question | +0.18‡ | 66 (57) | 12 (5–25) | 125 (54) | 10 (5–20) | 38 (16) | 7 (0–10) | 2 (1) | 2† |

| Identifying resources | +0.09 | 58 (25) | 10 (5–20) | 112 (49) | 10 (5–20) | 52 (23) | 10 (0–20) | 6 (3) | 8 (1–10) |

| Mentorship | +0.04 | 129 (56) | 10 (2–20) | 81 (35) | 10 (5–20) | 18 (8) | 8 (1–10) | 2 (1) | 5† |

| Having enough time | +0.02 | 72 (31) | 10 (4–20) | 95 (41) | 10 (5–20) | 58 (25) | 10 (0–20) | 5 (2) | 15 (10–25) |

| Agreement with belief | |||||||||

| Strongly agree | Somewhat agree | Somewhat disagree | Strongly disagree | ||||||

| Belief | ρ | n (%) | Research % | n (%) | Research % | n (%) | Research % | n (%) | Research % |

| Research is exciting | +0.69‡ | 47 (21) | 30 (20–30) | 103 (45) | 10 (5–20) | 47 (21) | 5 (0–10) | 32 (14) | 0 (0–0) |

| PEM has unanswered questions | +0.49‡ | 90 (39) | 18 (10–30) | 108 (47) | 10 (0–15) | 26 (11) | 0 (0–9) | 6 (3) | 0 (0–0) |

| I have a specific topic of interest | +0.41‡ | 98 (42) | 15 (10–25) | 104 (45) | 10 (0–15) | 26 (11) | 0 (0–10) | 3 (1) | 0† |

| Research moves PEM forward | +0.26‡ | 169 (74) | 10 (5–20) | 53 (23) | 10 (0–10) | 7 (3) | 0 (0–5) | 0 | N/A |

| Need help obtaining mentorship | −0.03 | 31 (13) | 10 (3–22) | 68 (29) | 10 (5–20) | 80 (35) | 10 (0–15) | 52 (23) | 12 (5–25) |

Research % given as median and interquartile range predicted clinical research time

Positive ρ indicates decreasing barrier correlated to increasing predicted clinical research time.

Too few observations to calculate 25th and 75th percentiles

p < 0.05

One hundred ninety-four (83.9%) participants agreed they had sufficient clinical research mentorship. There was no difference in likelihood of a clinical research career between those with adequate mentorship (10%, IQR 5–20) and those without (7.5%, IQR 1–13; p=0.17).

Beliefs Regarding Research

Respondents who believed research is exciting, that PEM has unanswered research questions, who were interested in a specific research topic, and who believed that research moves PEM forward reported higher predicted clinical research time (p<0.001 for all) (Table 2). Of the 150 respondents who agreed research was exciting, 65 (43%) predicted a clinical research career, compared with 4/79 (5%) among those who disagreed (p<0.001).

All significant barrier and belief correlations remained so after adjustment for multiple comparisons.

Discussion

A majority of PEM fellows arrived to fellowship with prior research experience and state they have sufficient mentorship at their training institution. Yet, only one in three PEM fellows plans to focus a substantial proportion of their future faculty careers on clinical research. Fellows with stated excitement and interest in a research were more likely to intend research as part of their career, and intention is a strong predictor of later research involvement.17 In order to develop the next generation of PEM researchers, faculty should identify fellows with defined interest early in their fellowship program, and prioritize fostering fellow engagement and excitement in research curricula and mentoring relationships. Development of the next generation of PEM researchers is paramount, as these future investigators are necessary to lead discoveries in prehospital and emergency care for children.

Nearly all PEM fellows plan careers centered on patient care, which underscores that the most likely reason residency graduates enter PEM is not to pursue research.18 Nearly half of current PEM fellows believe there should be an option to have a shortened fellowship duration for those pursuing primarily clinical careers.5 However, the need for future PEM investigators is clear. Priorities of PEM research are ever-expanding, but the number of fellows entering the research workforce remains low.4 Challenges such as increased competition for grant funding, lack of diversity among established researchers, difficulty securing protected time as junior faculty, availability of institutional resources, and increased interest in alternative scholarly pursuits, such as quality improvement and implementation science, may have made choice of a research career less appealing to fellow trainees.9,17

Excitement and belief in the importance of research were associated with future plans to participate in research. This may lead to increased eagerness, which fellowship directors believe is linked to research competency.19 Current external research funding was also predictive of a planned research career; the decision to pursue funding may reflect underlying enthusiasm for research. Barriers to performing research and sufficiency of research mentorship during fellowship were less predictive of future research interest, and therefore work to lower barriers to research may not increase the rate of planned research careers. Research is only one of a number of important factors in selection of PEM fellows.20–22 However, with more applicants than available fellowship positions, programs could consider prioritizing research at the time of applicant selection and identifying potential future investigators at this early stage.

Expectations for fellows have changed over time. Fellows must complete a scholarly activity during training, but some now opt to complete other forms of scholarship such as quality improvement studies, curriculum development, or administrative projects. No longer is completion of a clinical research project necessary or required. However, special effort to mentor and encourage fellows and new faculty with interest and excitement in research could lead to careers with a substantial research component.

How can PEM fellowships generate excitement about research? One third of fellows attends the annual National PEM Fellows’ Conference each year; attendance is associated with increased confidence in conducting research and increased intention to pursue and expand research opportunities.23 Fellowship curricula designed to foster curiosity, focusing mentorship on identifying research of highest interest to specific trainees, as well as increased national collaboration and mentorship could increase research enthusiasm. Additionally, for the half of fellows whose interest in research began prior to fellowship, developing curricula that take into account each fellow’s level may be valuable. In other medical fields, highly structured curricula and influential mentors predict interest in research and later research productivity.24–26 Half of PEM fellows participate in a hospital-based scholarly curriculum designed for all pediatric fellows, and our findings suggested participation in such activities should be increased. However, beyond these cross-disciplinary research training efforts, the development of PEM-specific research curricula might be used to increase camaraderie and relevance of the presented material to clinical research interests.5

This study had several limitations. First, participants who chose to respond may not be representative of the larger population of PEM fellows. However, our sample had a similar makeup of geography, gender, and fellowship stage as national data with complete ascertainment. Second, as a cross-sectional study, association may not reflect causation. For instance, it is possible that those already interested in pursuing research careers become excited and not the reverse. Third, our outcome was predicted clinical research time rather than actual clinical research time, though this prediction measures fellows’ intentions. Intentions are a crucial precursor to action; without the intention to incorporate research into their careers, fellowship graduates are unlikely to do so.17 Given the challenge of funding research efforts, fellow research intention may not result in later participation in research. Fourth, absent a consensus of what percentage of time constitutes a clinical research career, we chose to set a cutoff of 20% to represent one workday per week. We acknowledge that in some contexts, other cutoffs may be appropriate. Fifth, respondents may have had different perceptions of what constitutes research. However, we believe our definition of research would minimize the differences in perceptions. Sixth, we did not define mentorship for respondents in order to allow respondents to self-define what was relevant to them, however this self-definition may have impacted responses to whether mentorship was sufficient. Finally, the data were observational and therefore intervening on possible predictors may not result in improved outcomes.

Conclusion

In conclusion, only one in three PEM fellows plans a career with significant clinical research time within the first five years after completion of fellowship. Early research interest in fellowship, and fellow excitement about research were most associated with interest in clinical research as a faculty member. In order to develop the next generation of PEM researchers, faculty should identify fellows with defined interest early in their fellowship program, and foster fellow engagement and excitement in research curricula. Development of the next generation of PEM researchers is important, as these future investigators are necessary to lead discoveries in prehospital and emergency care for children.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This project was supported by grant number T32HS000063 from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

References

- 1.Committee on the Future of Emergency Care in the United States Health System. Emergency Care for Children: Growing Pains. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Foltin GL, Dayan P, Tunik M, et al. Priorities for pediatric prehospital research. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2010;26(10):773–777. doi: 10.1097/PEC.0b013e3181fc4088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.American Board of Pediatrics. General Criteria for Subspecialty Certification. [Accessed May 18, 2016]. Available at: https://www.abp.org/content/general-criteria-subspecialty-certification. [Google Scholar]

- 4.American Board of Pediatrics. 2015–2016 Workforce Data. Chapel Hill, NC: 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Freed GL, Dunham KM, Moran LM, et al. Specialty Specific Comparisons Regarding Perspectives on Fellowship Training. Pediatrics. 2014;133(Supplement):S76–S77. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brown J. National Institutes of Health Support for Individual Mentored Career Development Grants in Emergency Medicine. Acad Emerg Med. 2014;21(11):1269–1273. doi: 10.1111/acem.12517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ranney ML, Limkakeng AT, Carr B, et al. Improving the Emergency Care Research Investigator Pipeline: SAEM/ACEP Recommendations. Acad Emerg Med. 2015;22(7):849–851. doi: 10.1111/acem.12699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gorelick MH, Schremmer R, Ruch-Ross H, et al. Current Workforce Characteristics and Burnout in Pediatric Emergency Medicine. Acad Emerg Med. 2016;23(1):48–54. doi: 10.1111/acem.12845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Reynolds S, Chang T, Iyer S, et al. Essentials of PEM Fellowship: Part 5: Scholarship Prepares Fellows to Lead as Pediatric Emergency Specialists. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2016;32(9):645–647. doi: 10.1097/PEC.0000000000000896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lewis RJ. Academic Emergency Medicine and the “Tragedy of the Commons” defined. Acad Emerg Med. 2004;11(5):423–427. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2004.tb02399.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.National Resident Matching Program. NRMP Program Results 2011–2015 Specialties Matching Service. Washington, DC: 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, et al. Research electronic data capture REDCap)--a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42(2):377–381. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McAneney C. Pediatric emergency medicine fellowship programs. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2015;31(4):308–314. doi: 10.1097/PEC.0000000000000431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.United States Census Bureau. [Accessed April 8, 2016];Census Regions and Divisions of the United States. Available at: http://www2.census.gov/geo/pdfs/maps-data/maps/reference/us_regdiv.pdf.

- 15.Holm S. A Simple Sequentially Rejective Multiple Test Procedure. Scand J Stat. 1979;6(2):65–70. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wickham H. ggplot2: Elegant Graphics for Data Analysis. New York: Springer-Verlag; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Krupat E, Camargo CA, Strewler GJ, et al. Factors associated with physicians’ choice of a career in research: a retrospective report 15 years after medical school graduation. Adv Heal Sci Educ. 2016 Apr; doi: 10.1007/s10459-016-9678-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Freed GL, Dunham KM, Switalski KE, et al. Pediatric fellows: perspectives on training and future scope of practice. Pediatrics. 2009 Jan;123:S31–S37. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-1578I. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Titus MO, Losek JD, Givens TG. Pediatric Emergency Medicine Fellowship Research Curriculum. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2009;25(9):550–554. doi: 10.1097/PEC.0b013e3181b4f623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Poirier MP, Pruitt CW. Factors used by pediatric emergency medicine program directors to select their fellows. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2003;19(3):157–161. doi: 10.1097/01.pec.0000081236.98249.ed. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bradley T, Clingenpeel JM, Poirier M. Internal Applicants to Pediatric Emergency Medicine Fellowships and Current Use of the National Resident Matching Program Match. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2015;31(7):487–492. doi: 10.1097/PEC.0000000000000481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.National Residency Matching Program. Results and Data: Specialty Matching Service. [Accessed April 14, 2016]. Available at: http://www.nrmp.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/02/Results-and-Data-SMS-2015.pdf. Published 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jaffe DM, Knapp JF, Jeffe DB. Final evaluation of the 2005 to 2007 National Pediatric Emergency Medicine Fellows’ Conferences. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2009;25(5):295–300. doi: 10.1097/PEC.0b013e3181a34159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Steiner JF, Lanphear BP, Curtis P, et al. Indicators of early research productivity among primary care fellows. J Gen Intern Med. 2002;17(11):854–860. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2002.10515.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Posporelis S, Sawa A, Smith GS, et al. Promoting Careers in Academic Research to Psychiatry Residents. Acad Psychiatry. 2014;38(2):185–190. doi: 10.1007/s40596-014-0037-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ahmad S, De Oliveira GS, McCarthy RJ. Status of anesthesiology resident research education in the United States: Structured education programs increase resident research productivity. Anesth Analg. 2013;116(1):205–210. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0b013e31826f087d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.