Abstract

Background

The burden of HIV remains heaviest in resource-limited settings, where problems of losses to care, silent transfers, gaps in care, and incomplete mortality ascertainment have been recognized.

Methods

Patients in care at Academic Model Providing Access to Healthcare (AMPATH) clinics from 2001–2011 were included in this retrospective observational study. Patients missing an appointment were traced by trained staff; those found alive were counseled to return to care (RTC). Relative hazards of RTC were estimated among those having a true gap: missing a clinic appointment and confirmed as neither dead nor receiving care elsewhere. Sample-based multiple imputation accounted for missing vital status.

Results

Among 34,522 patients lost to clinic, 15,331 (44.4%) had a true gap per outreach, 2,754 (8.0%) were deceased, and 837 (2.4%) had documented transfers. Of 15,600 (45.2%) remaining without active ascertainment, 8,762 (56.2%) with later RTC were assumed to have a true gap. Adjusted cause-specific hazard ratios (aHR) showed early outreach (an ≤8-day window, defined by grid-search approach) had twice the hazard for RTC vs. those without (aHR=2.06; p<0.001). Hazard ratios for RTC were lower the later the outreach effort after disengagement (aHR=0.86 per unit increase in time; p<0.001). Older age, female sex (vs. male), ART use (vs. none), and HIV status disclosure (vs. none) were also associated with greater likelihood of RTC, and higher enrollment CD4 count with lower likelihood of RTC.

Conclusion

Patient outreach efforts have a positive impact on patient RTC, regardless of when undertaken, but particularly soon after the patient misses an appointment.

Keywords: retention in care, sample-based multiple imputation, mortality ascertainment, re-engagement in care, outreach

Background

The HIV epidemic remains a serious global health threat, affecting more than 35 million individuals, particularly in resource-limited settings, where the overwhelming burden and incidence of disease still lies.(1) However, there have been encouraging recent trends of reduced incidence and mortality alongside antiretroviral therapy (ART) program scale-up and ART provision for more than 18 million people, with more than 10.3 million people receiving therapy in eastern and southern Africa.(1) Even though this represents treatment for only 54% of the more than 19 million HIV-positive individuals in the most affected setting, the scale of the intervention represents unique programmatic challenges.(1) Indeed, as antiretroviral therapy guidelines have expanded to accommodate a treatment-as-prevention paradigm, retention in continuous care has remained a critical point of loss in the HIV care continuum, representing a barrier to optimizing individual patient outcomes and population reductions in transmission.(2,3)

The problems of losses to care, silent transfers (i.e., undocumented transfer from one program to another), true gaps in care (i.e., complete absence from medical care for defined periods of time with resumption of care at subsequent time points), and incomplete mortality assessment in these settings have been widely recognized, with a number of studies describing the influence of individual-level and program-level factors on these outcomes.(4,5) Despite growing awareness of the problem and significant improvements in retention and ART adherence, particularly at sites offering adherence support services, counseling services, educational materials and food rations, program attrition has persisted to an estimated rate between 0.5% and 2.5% per month, with as much as 30% of patients being lost to clinic in the first year after ART initiation, depending on the setting.(4,6–12). One pernicious aspect of program attrition is that it hinders efforts to monitor and evaluate care and treatment programs and, by extension, hampers any intervention which may result in improving patient retention. This is because, as a rule, clinical outcomes are not known among patients who have been truly lost to a program and thus, attrition results in incomplete outcome ascertainment for a significant proportion of these cohorts. Consequently, inferences about these populations that do not account for incomplete outcome ascertainment among those lost to clinic may be subject to biases which may be significant.(13)

However, it is often impractical or impossible for most programs in resource-limited settings, which may lack comprehensive death registries, to establish the vital status of patients who are no longer in care at the program and, because of limited communications among programs, it is virtually impossible to ascertain whether a patient is receiving care elsewhere. The end result is a breakdown in the ability of programs and systems of care to perform monitoring and evaluation of programs and programmatic interventions to improve care and patient outcomes. A number of studies have noted these inferential barriers due to incomplete outcome ascertainment and have proposed potential analytic remedies.(13–17) Among the solutions considered is double-sampling among those lost to care (using either a random sample (14,17,18) or over-sampling individuals with specific profiles (19)) and intensive tracing to ascertain outcomes. Double-sampling has been particularly appealing because only a small sample of those lost needs to be traced and the approach addresses selection bias due to differential emigration in a methodologically transparent and resource-efficient manner.

Virtually all of these studies however, constitute a public health evaluation of patient outcomes and treatment programs. With essentially no exceptions, this powerful methodology has not been used to date to assess interventions that may improve patient retention or induce patients who have disengaged from care to re-engage. While a few studies in Africa have shown that programs that attempt to re-engage patients back into care have some success(10), and re-integration of patients previously lost to clinic back into care should improve clinical outcomes, most studies taking the necessary next steps and quantifying the success of outreach strategies to improve re-engagement after losses to clinic have been conducted in the United States.(20–26) The few studies assessing re-engagement in low-income countries have focused more on descriptions of factors associated with attrition, have assessed only groups such as pregnant women, or have been qualitative in nature.(27–32) No studies however have quantitatively evaluated the success of specific strategies or their timing to maximize patient re-engagement in care after loss to care.

Beyond describing the epidemiology of HIV and the movement of populations in and out of care, evidence is now required to transform epidemiologic understanding into public health action, re-establishing retention in HIV care and access to continuous ART.(33) The re-engagement of individuals lost to care is an essential and understudied stage in the HIV continuum of care.(32) In this report, we use a sampling-based method as described above to undertake a rigorous analysis of the impact and timing of patient outreach on re-engagement in care among HIV-infected patients receiving care in a large African HIV care and treatment program who have experienced gaps in care over the course of a decade.

Methods

Study population and measurement

Patients receiving care at the Academic Model Providing Access to Healthcare (AMPATH) between 2001 and 2011 were included. AMPATH is a partnership initially established between the Moi University School of Medicine in Eldoret, Kenya, the Indiana University School of Medicine, and Brown Medical School in 2001. AMPATH is a member of ART-LINC. AMPATH now provides HIV care and treatment to over 50,000 adults and children living with HIV/AIDS in 19 clinics throughout western Kenya. Patients are managed according to National Kenyan protocols, which are consistent with WHO guidelines. The majority of patients receive free HIV care including basic laboratory services and ART. Clinic visits occur monthly for all patients on ART unless alternative arrangements have been made with their health care provider. Patients who are not yet eligible for treatment are seen monthly or bi-monthly depending on their immunologic status and other factors in their health profile. Standard paper data collection forms are used at enrolment to the program and at each subsequent visit.

AMPATH enacted a patient outreach program where patients failing to appear for a scheduled appointment are traced by trained patient outreach staff in the community, based on location information the patients themselves provide upon enrollment.(13,34) Patients traced and found alive are given counseling and encouragement to return to care. The effect of this intervention on return to care, among patients found alive through outreach, is the focus of this study.

We used patient-level data obtained prospectively through routine clinical care at AMPATH and data obtained through the outreach encounter. This information has been recently incorporated into the AMPATH Medical Record System (AMRS), which is based on the OpenMRS platform (openmrs.org). Data from routine clinical care were processed and validated through standard operating procedures within the East Africa Region of the International Epidemiologic Databases to Evaluate AIDS (IeDEA-EA; www.iedea-ea.org) of which AMPATH is a participating site. All data and research were sanctioned by the AMPATH Institutional Research and Ethics Committee and the Indiana University Institutional Review Board as well as all appropriate bodies within the two institutions pursuant to local and national regulations as appropriate.

Statistical analysis

Analysis of return or re-engagement in care was based on patients who were lost to clinic and had a true gap in care. A “true gap in care” refers to a patient having not appeared for a scheduled clinic appointment and being neither dead nor receiving care elsewhere. This differs from an apparent gap, which would occur when individuals are absent from the clinic but receive care elsewhere without knowledge from the program of origin. This means unreported deaths and undocumented (“silent”) transfers to other treatment facilities do not constitute a true gap in care.

Based on a sample of lost patients whose true vital status was actively ascertained through outreach, we applied a multiple imputation methodology to impute missing vital status of lost patients who were not reached and for whom we did not have true vital status ascertained. This was crucial for our analysis because only living patients with a true gap in care were at risk of returning to care. Imputation of vital status has also been shown to greatly improve the validity of inferences based on mortality outcomes in these settings, where ascertainment may be problematic.(13–16) The multiple imputation used a missing at random assumption (MAR).(35–37) The MAR assumption here is translated as: the probability of missing data (i.e., unsuccessful outreach) does not depend on underlying true (vital) status given the covariates in the imputation model to predict missing vital status. Simply, patients not traced are no more or less likely to be deceased compared to similar patients who were successfully traced. The covariates used in the imputation model were time to loss to clinic from enrollment, age at enrollment, gender, CD4 count and WHO stage at enrollment, ART status at the time of the missed appointment, HIV status disclosure, and travel time to clinic. These variables along with additional data available through patient outreach, make the MAR assumption more plausible here.

Successful outreach (SOR) was defined as an outreach encounter where a patient lost to clinic was either successfully located if alive or had true vital status ascertained if deceased. Supplementary analyses assessed outcomes after early versus late or unsuccessful outreach efforts. These analyses complement the primary analysis by providing greater granularity in identifying an “optimal” time of successful outreach and identifying the risks of return to care about that cut-point, as opposed to modeling outreach time continuously. The definition of “early” was based on a grid search in which we looked for the number of days from flagging a patient as lost to clinic to successful outreach that achieved the smallest Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) value. In this grid search we evaluated all times from 1 day to 100 days until the outcome of SOR (Supplementary Figure 1).

Cumulative probability of return to care was estimated based on the non-parametric Kaplan-Meier estimator applied to patients with observed or imputed true gap in care, using the multiple imputation method described above. Hazards of return to care were estimated by the Cox model.

Sensitivity analysis

One complication of return to care analyses among patients with true gaps is that deaths occurring while not in care are not recorded. While it is possible to identify, through patient outreach, true vital status and engagement in care, it is not possible to obtain additional information to ascertain who, among those with a true gap in care, did not return because they disengaged from care altogether, transferred to (i.e., re-engaged in care in) another clinic or died. This is because these outcomes occur after the outreach encounter is completed and, with few exceptions, no additional tracing efforts were initiated on patients who, after being traced, did not return to care at the original clinic. Consequently, there are no observable data that can be used to identify patients who died, which can be used in turn to inform estimates of corresponding death times. This issue of unobserved mortality is only relevant to the patients that did not re-engage in care during the study period.

In order to evaluate the robustness of our inferences to various scenarios regarding unobserved out-of-care mortality, we performed sensitivity analyses speculating on the proportion of patients who died or transferred to another clinic, among those who had a gap in care. In these, we have simplistically excluded silent transfers (a small percentage within the AMPATH program due to comprehensive coverage of its catchment area) and only considered scenarios involving increasingly larger proportions of death among those with a gap in care. Sensitivity analyses were implemented as follows: initially, we fitted a semi-parametric cause-specific hazards model to assess effect on mortality while in care of gender, age when lost to clinic, CD4 count and WHO stage at enrollment, being on ART, HIV status disclosure and travel time to clinic. We imputed unknown vital status among patients lost to the program and not reached using multiple imputation, described above. In this manner, we assigned these patients our best guess whether the reason for their loss to program was disengagement from care versus being an unobserved death. We then approximated baseline hazards of this model with a Weibull-shaped hazard and used estimated effect parameters from the resulting model to simulate times to death while not in care. We assumed different levels of baseline mortality for those not returning to care during the study period, ranging from slightly lower to a much higher out-of-care mortality compared to observed in-care mortality. Based on simulated mortality, we used the Aalen-Johansen estimator(38) and the semiparametric proportional cause-specific hazards model to analyze occurrence of a patient returning to care in the presence of out-of-care mortality.

Results

Patient characteristics

Among 108,221 who were enrolled from 2001 to 2011 in one of the AMPATH clinics, 34,522 adult patients were identified as being lost to clinic. Of them, 44.4% (15,331/34,522) had a true gap in care as determined by outreach, 8.0% (2,754/34,522) were deceased and 2.4% (837/34,522) had a documented transfer to another HIV care facility; the remaining 45.2% (15,600/34,522) of patients did not have their true status ascertained. Of those patients, 56.2% (8,762/15,600) later returned to care and, because of this, were assumed to have a true gap in care. From this point forward, all analyses are based on patients with either a confirmed status of true gap in care (n=24,093=15,331+8,762), or those with an imputed gap in care among patients without ascertained vital status who never returned to care (n=6,838=15,600–8,762). About one third (10,653/30,931=36.2%) of these patients presented to care with a CD4 count ≥ 350 cells/μL, and a similar proportion (9,594/30,931=37.0%) presented to care with a WHO stage 3 or 4 diagnosis. Two thirds of patients had disclosed their HIV status (18,599/30,931=64.4%) while 54.9% (16,972/30,931) were on ART at the last clinic visit prior to being identified as lost to clinic.

The median (IQR) age at the time when patients were flagged as being lost to clinic of enrollment was 35.9 (29.8, 43.2) years. The majority of the patients were female (21,091/30,931=68.2%), a small proportion of whom were found to be pregnant at enrollment (2,311/21,091=11.0%). Median (IQR) CD4 cell count at the point of loss to clinic was 255 (117, 444) cells/μL. Patient characteristics according to their reason for any gap in care at their clinic of enrollment are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Descriptive characteristics of the study population, according to the reason for a gap in care (“true gap,” which was a confirmed loss to clinic, or “unknown”) at the clinic of enrollment, and overall (N=30,931).

| Reason for gap in care | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| True Gap (Total N=24, 093) N (%) |

Unknown (Total N=6,838) N (%) |

Overall (Total N=30,931) N (%) |

|

| Age at beginning of gap in care (years) | |||

| 18–24.9 | 1978 (8.2) | 1037 (15.2) | 3015 (9.7) |

| 25–34.9 | 8531 (35.4) | 2831 (41.4) | 11362 (36.7) |

| 35–44.9 | 8266 (34.3) | 1920 (28.1) | 10186 (32.9) |

| 45+ | 5318 (22.1) | 1050 (15.4) | 6368 (20.6) |

| Gender | |||

| Male | 7732 (32.1) | 2108 (30.8) | 9840 (31.8) |

| Female & non-pregnant | 14570 (60.5) | 4210 (61.6) | 18780 (60.7) |

| Female & pregnant at enrolment | 1791 (7.4) | 520 (7.6) | 2311 (7.5) |

| On ART before gap in care | |||

| No | 9634 (40.0) | 4325 (63.2) | 13959 (45.1) |

| Yes | 14459 (60.0) | 2513 (36.8) | 16972 (54.9) |

| HIV status disclosed | |||

| No | 7818 (34.6) | 2481 (39.4) | 10299 (35.6) |

| Yes | 14779 (65.4) | 3820 (60.6) | 18599 (64.4) |

| CD4 at enrollment | |||

| <350 | 15330 (65.5) | 3482 (57.5) | 18812 (63.8) |

| 350+ | 8078 (34.5) | 2575 (42.5) | 10653 (36.2) |

| WHO stage 3/4 at enrollment | |||

| ½ | 13098 (62.9) | 3233 (63.2) | 16331 (63.0) |

| ¾ | 7712 (37.1) | 1882 (36.8) | 9594 (37.0) |

| Travel time to clinic | |||

| 0–60 minutes | 14996 (64.2) | 4293 (65.8) | 19289 (64.6) |

| >60 minutes | 8348 (35.8) | 2233 (34.2) | 10581 (35.4) |

| Successful outreach within 8 days | |||

| No | 9915 (41.2) | 6838 (100.0) | 16753 (54.2) |

| Yes | 14178 (58.8) | 0 (0.0) | 14178 (45.8) |

| Return to care after the 1st gap | |||

| No | 3569 (14.8) | 6838 (100.0) | 10407 (33.6) |

| Yes | 20524 (85.2) | 0 (0.0) | 20524 (66.4) |

| Median (IQR) | Median (IQR) | Median (IQR) | |

|

| |||

| Age at beginning of gap (years) | 36.5 (30.5, 43.8) | 33.3 (27.4, 40.8) | 35.9 (29.8, 43.2) |

| CD4 at enrollment | 246 (113, 431) | 293 (137, 482) | 255 (117, 444) |

Models of returning to HIV care

We performed multivariable Cox models of the cause-specific hazard of returning to care. Outreach efforts were found to always have some benefit, with regard to the probability of returning to care, regardless of the lapse between the last clinic date and the date of returning to care: the hazard of returning to care was always greater than 1. From the interaction between successful outreach and (log) time (Table 2), we can infer that, for every log time unit delay (i.e., as outreach is delayed relative to the time of disengagement from care), the hazard of returning to care is reduced by about 14% (adjusted hazard ratio [HR]=0.86; 95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.85, 0.88).

Table 2.

Factors affecting the hazard of return to care. Results from a multivariable Cox proportional hazards model accounting for lack of proportionality in the hazards by the inclusion of the effect of interaction of successful outreach with the logarithm of time included to capture the time dependence of the effect of successful outreach over time.

| HR | 95% CI | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age at beginning of gap in care (years) | |||

| 18–24.9 | 1 | ||

| 25–34.9 | 1.202 | (1.129, 1.280) | <0.001 |

| 35–44.9 | 1.378 | (1.292, 1.470) | <0.001 |

| 45+ | 1.500 | (1.401, 1.606) | <0.001 |

| Gender | |||

| Male | 1 | ||

| Female & non-pregnant | 1.053 | (1.018, 1.090) | 0.003 |

| Female & pregnant | 1.175 | (1.100, 1.256) | <0.001 |

| Successful outreach (estimate at 1 year) | |||

| No | 1 | ||

| Yes | 1.427 | (1.336, 1.525) | <0.001 |

| Successful outreach * log(time1) | |||

| per unit | 0.863 | (0.846, 0.880) | <0.001 |

| On ART | |||

| No | 1 | ||

| Yes | 1.601 | (1.542, 1.663) | <0.001 |

| HIV status disclosed | |||

| No | 1 | ||

| Yes | 1.055 | (1.022, 1.089) | 0.001 |

| CD4 at enrollment | |||

| <350 | 1 | ||

| 350+ | 0.951 | (0.914, 0.989) | 0.011 |

| WHO stage at enrollment | |||

| 1/2 | 1 | ||

| 3/4 | 0.994 | (0.961, 1.028) | 0.732 |

| Travel time to clinic | |||

| 0–60 minutes | 1 | ||

| >60 minutes | 1.015 | (0.983, 1.049) | 0.356 |

Years since flagged as lost

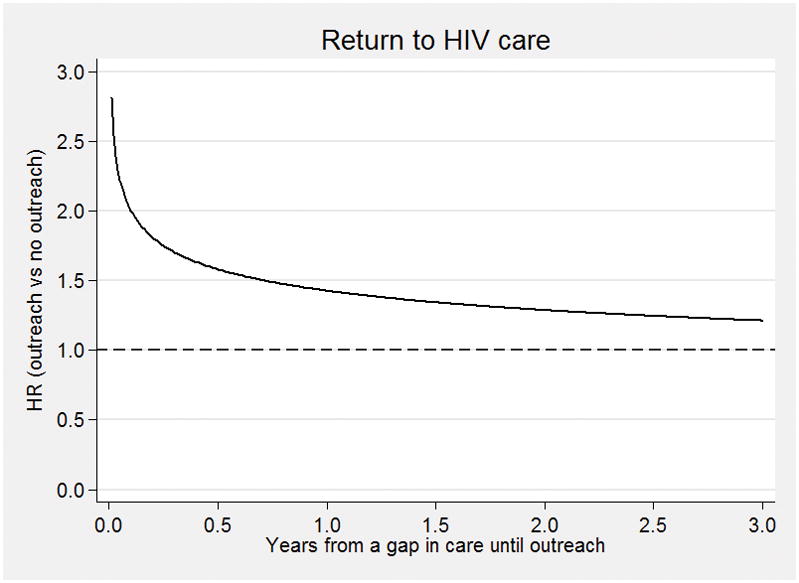

The effect of early outreach was analyzed further by using an 8-day window, based on a grid search approach, in supplementary analyses. When dichotomizing successful outreach as early vs. late in this manner, we detected similar associations between return to HIV care and demographic and clinical characteristics as in the primary analyses where continuous time was used (Table 3). Patients reached early (i.e., within 8 days from their missed visit) had approximately two times the hazard to return to care (HR=2.06; 95% CI: 1.99, 2.11) compared to those who did not successfully receive outreach or received outreach late (i.e., after 8 days from their missed clinic visit). In a naïve complete-case analysis, excluding the 6,838 individuals for whom the imputation procedure was used in the primary analysis to predict missing vital status, this effect was drastically attenuated (HR=1.09; 95% CI: 1.06, 1.12), though still statistically significant and in the same direction as when using the full study population (Supplementary Table 1). Importantly, using the entire study population, the earliest outreach was associated with an HR above 2.5, while outreach before 6 months had an HR between 1.6 and 2.0, outreach between 6 and 18 months having a HR between 1.3 and HR 1.6, and outreach after 18 months having minimal effect (HR<1.3) (Figure 1).

Table 3.

Effect of early outreach on the hazard of returning to care. Results from a multivariable Cox proportional hazards model.

| HR | 95% CI | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age at beginning of gap in care (years) | |||

| 18–24.9 | 1 | ||

| 25–34.9 | 1.210 | (1.138,1.287) | <0.001 |

| 35–44.9 | 1.393 | (1.308,1.482) | <0.001 |

| 45+ | 1.521 | (1.420,1.629) | <0.001 |

| Gender | |||

| Male | 1 | ||

| Female & non-pregnant | 1.053 | (1.019,1.088) | 0.002 |

| Female & pregnant | 1.183 | (1.113,1.257) | <0.001 |

| Successful outreach within 8 days | |||

| No | 1 | ||

| Yes | 2.056 | (1.999,2.114) | <0.001 |

| On ART | |||

| No | 1 | ||

| Yes | 1.617 | (1.553,1.682) | <0.001 |

| HIV status disclosed | |||

| No | 1 | ||

| Yes | 1.057 | (1.028,1.087) | <0.001 |

| Initial CD4 | |||

| <350 | 1 | ||

| 350+ | 0.956 | (0.921,0.992) | 0.016 |

| WHO stage 3/4 | |||

| 1/2 | 1 | ||

| 3/4 | 0.99 | (0.957,1.024) | 0.557 |

| Travel time to clinic | |||

| 0′–60′ | 1 | ||

| >60′ | 1.012 | (0.982,1.044) | 0.433 |

Figure 1.

Time-dependent hazard ratio – HR – for return to care (ratio of successful outreach versus unsuccessful or no outreach) dependent on time of initiation of outreach relative to disengagement. The horizontal dashed line at HR=1 (reference) implies no difference attributable to outreach. HR>1 implies benefit (higher likelihood of return), while HR<1 indicates a detrimental effect of outreach.

In the primary model, compared with younger patients (age 18–24.9 years), older patients had increased hazard ratios of return to care, with HR=1.20 (95% CI: 1.13, 1.28) for those aged 25–34.9, HR=1.38 (95% CI: 1.29, 1.47) for those aged 35–44.9, and HR=1.50 (95% CI: 1.40, 1.61) for those aged ≥45 years. Compared to males, female patients, whether non-pregnant (HR=1.05, 95% CI: 1.02, 1.09) or pregnant (HR=1.18, 95% CI: 1.10, 1.26) had a greater likelihood of return to care. Both ART use (HR=1.60, 95% CI: 1.54, 1.66 vs. no ART), and disclosure of HIV status (HR=1.06, 95% CI: 1.02, 1.09 vs. none) were also associated with greater likelihood of returning to care (Table 2). In contrast, higher CD4 count at enrollment was associated with lower likelihood of returning to care (HR=0.95, 95% CI: 0.91, 0.99) (Table 2). Adjusted associations between these covariates and return to care were similar in both magnitude and direction in the supplementary model using an 8-day window for successful outreach, both when using the full study population (Table 3) and when using the naïve complete-case analysis in which the 6,838 individuals with missing true gap status were excluded (Supplementary Table 1).

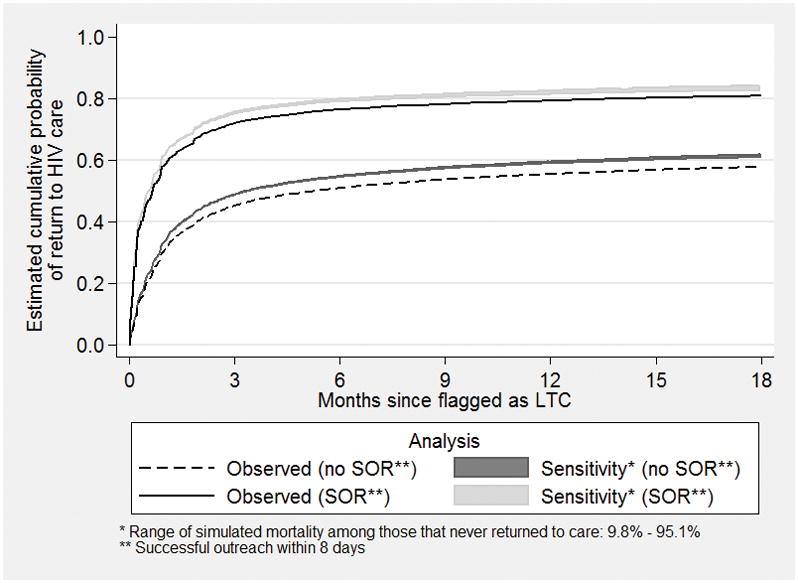

Sensitivity analyses

We performed sensitivity analyses by considering numerous scenarios of patient mortality after true gaps in care as described in the Methods above. The time-dependent effect of outreach based on the sensitivity analyses was essentially identical to the one from the main analysis. Specifically, the time-dependent effect (HR) of outreach at 1 year ranged from 1.34 to 1.55, and was highly statistically significant in all cases (p-value<0.001). The corresponding effect of the interaction of outreach with the logarithm of time ranged from 0.87 to 0.91, and was statistically significant in all cases, too (p-value<0.001). This indicates that our results are robust to various scenarios regarding the mortality of those that never returned in care. This is supported by the extremely narrow intervals around the cumulative incidence estimates (Figure 2; see grey areas around the curves) which imply that, under widely differing assumptions about the true rate of out-of-care mortality, our observations outlined in the previous section (which did not consider the unknown mortality after a gap in care) were quite robust to potential under-ascertainment of mortality as a competing risk for re-engagement in care with the adjusted hazard ratios falling in the range of 1.96 to 2.03 between successful outreach and no outreach (analyses not shown).

Figure 2.

Estimates of the cumulative probability of returning to HIV care after a true gap in care (time zero) according to whether there was a successful outreach (SOR) effort within 8 days from the date that a patient was flagged as lost to clinic (LTC), which was the beginning of the gap in care. Estimates are based on the analysis of the observed data (black solid and dashed lines) and the sensitivity analysis regarding various scenarios of the unobserved out-of-care mortality (shaded areas corresponding to a range of mortality rates while out of care).

Discussion

Among those with true gaps in care, outreach had a clinically significant impact on returning to care (HR=2.056) even after controlling for other predictors commonly reported to be associated with the likelihood of gaps in care such as older age, pregnancy, lower CD4 count at enrollment, and ART. Notably, the relative effect of outreach on the likelihood of return to care had a strong time dependence from when the gap in care was identified. As shown in Figure 1, the hazard ratio for returning to HIV care was higher the closer the outreach effort was made to the time of disengagement from care (Figure 1). However, because people often spontaneously return to care soon after a gap is identified (e.g. approximately half of the persons in our study with a gap in care returned to care spontaneously within 3 months), the absolute effect of outreach rises and then falls, with a maximal effect occurring between 1 and 6 months. Formal optimization approaches could be used to identify the health-maximizing time for outreach by considering the number of people additionally returned to care together with the health benefit from reducing the length of the gap.

Our observations recapitulate differences and patterns noted in studies assessing programmatic retention in care, as older age and lower CD4 count at enrollment and/or at ART initiation have previously been reported as strongly associated with better retention in care within similar settings (28,39–41) A notable difference of our study compared to previous reports is that our inferences were made with reference to a population already lost to clinic, versus the entire population engaged in care, which might be susceptible to saturation of treatment effect because individuals continuously retained in the entire population may not derive additional benefit from outreach efforts (e.g., appointment reminders) directed at them.

In a previous report on re-engagement in care, Layer, et al. [2014] noted multiple barriers to return, such as work relocation requirements, lack of transportation resources, time commitments caring for sick relatives, losing identification or clinical care access cards.(30) Particularly important was fear of subsequent mistreatment by clinic staff after missed appointments. Lack of health knowledge did not appear to be a barrier. Camlin [2016] identified a similar spectrum of factors, with poverty and transportation resources having a greater role, and fear of mistreatment by clinic staff also playing an important role.(32) Indeed, it is possible that the outreach effort was effective in part because it mitigated concerns over staff hostility or provided encouragement to patients.

There were limitations to this analysis. As with all observational studies, our analysis may have been subject to residual confounding of the relationship between measured factors and re-engagement in care. In addition, as revealed in sensitivity analyses, the true mortality rate during gaps in care may be slightly underestimated, and thus the population of individuals susceptible to re-engagement in any particular risk set may be slightly overestimated. However, our approach has mitigated many of these limitations. Our study benefited from rich data available on transfers of care and double-sampling techniques utilizing intensive tracing and mortality ascertainment to better characterize the patient population truly at risk of returning to clinic after a true gap in care. In fact, as the severely attenuated estimate from the naïve complete-case analysis demonstrates, the use of imputation to properly incorporate the population not directly observed during outreach but still at risk of returning to clinic mitigated a serious source of selection bias. The imputation was therefore crucial in obtaining more valid estimates for the effect of early outreach on return to care. In sensitivity analyses assuming a wide range of mortality rates for those lost to follow-up at the clinic of enrollment but not returning to care, inferences with respect to the cumulative probability of re-engagement in care and the differences in re-engagement due to successful outreach were not appreciably affected. Accordingly, our results are more likely to generalize to individuals who have true gaps in care, and are particularly robust to typical sources of bias.

Our results have an important policy impact. Within AMPATH, the outreach program had a clinically significant effect increasing the likelihood that individuals with a true gap in care returned to care, even after controlling for other risk factors and after verifying that the gaps were “true gaps” in care rather than undocumented (“silent”) transfers or unreported deaths. While programs continue to scale-up and enhance delivery of ART to key populations, efforts to prevent losses to follow-up and gaps in care will be essential in order to realize the full benefits of expanded access for both the individual and the HIV-uninfected population. As results from this study indicate, establishing outreach to patients absent from care could yield very high cumulative probabilities of re-engagement.

We conclude that patient outreach efforts have a positive impact on the likelihood of patient re-engagement in care, regardless of when they are undertaken, but particularly when initiated shortly after failure by the patient to keep a scheduled appointment. Our observations, which take into account the unknown outcome of patients with gaps in care, have the potential to inform both the possible benefit and optimal timing of such interventions. Outreach programs are an important component of ART programs which continue to scale up, especially if the cost-effectiveness of outreach efforts could be demonstrated to be favorable (meaning more health is bought with the same resources) compared to other programmatic priorities such as earlier initiation of ART, making second- and third-line ART regimens more available, and implementation of routine viral load testing. Indeed, future research on the cost-effectiveness of outreach interventions would inform its prioritization in the context of these multiple priorities. As current HIV treatment prevention efforts shift towards combination interventions, our results suggest that outreach may be a valuable constituent.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute Of Allergy And Infectious Diseases (NIAID), Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute Of Child Health & Human Development (NICHD), National Institute On Drug Abuse (NIDA), National Cancer Institute (NCI), and the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH), in accordance with the regulatory requirements of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number U01AI069911, (East Africa IeDEA Consortium), and Award Number U01AI069923 (Caribbean, Central and South America network for HIV epidemiology (CCASAnet) of IeDEA).

This work was also supported by the President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR) through USAID under the terms of Cooperative Agreement No. AID-623-A-12-0001 It is made possible through joint support of the United States Agency for International Development (USAID).

The contents of this journal article are the sole responsibility of the authors and of AMPATH and do not necessarily reflect the official views of the National Institutes of Health, USAID, or the United States Government.

References

- 1.UNAIDS. AIDS by the numbers: AIDS is not over, but it can be. Geneva: Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization. Consolidated guidelines on the use of antiretroviral drugs for treating and preventing HIV infection. 2013 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hirnschall G, Harries AD, Easterbrook PJ, Doherty MC, Ball A. The next generation of the World Health Organization’s global antiretroviral guidance. J Int AIDS Soc Switzerland. 2013;16:18757. doi: 10.7448/IAS.16.1.18757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lamb MR, El-Sadr WM, Geng E, Nash D. Association of adherence support and outreach services with total attrition, loss to follow-up, and death among ART patients in sub-Saharan Africa. PLoS One United States. 2012;7(6):e38443. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0038443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ware NC, Wyatt MA, Geng EH, Kaaya SF, Agbaji OO, Muyindike WR, Chalamilla G, Agaba PA. Toward an understanding of disengagement from HIV treatment and care in sub-Saharan Africa: a qualitative study. PLoS Med United States. 2013;10(1):e1001369. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001369. discussion e1001369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Odafe S, Torpey K, Khamofu H, Ogbanufe O, Oladele EA, Kuti O, Adedokun O, Badru T, Okechukwu E, Chabikuli O. The pattern of attrition from an antiretroviral treatment program in Nigeria. PLoS One United States. 2012;7(12):e51254. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0051254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nachega JB, Uthman OA, del Rio C, Mugavero MJ, Rees H, Mills EJ. Addressing the Achilles’ heel in the HIV care continuum for the success of a test-and-treat strategy to achieve an AIDS-free generation. Clin Infect Dis United States. 2014;59(Suppl 1):S21–7. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciu299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kessler J, Nucifora K, Li L, Uhler L, Braithwaite S. Impact and Cost-Effectiveness of Hypothetical Strategies to Enhance Retention in Care within HIV Treatment Programs in East Africa. Value Health United States. 2015;18(8):946–55. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2015.09.2940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rachlis B, Ochieng D, Geng E, Rotich E, Ochieng V, Maritim B, Ndege S, Naanyu V, Martin JN, Keter A, Ayuo P, Diero L, Nyambura M, Braitstein P. Implementation and operational research: evaluating outcomes of patients lost to follow-up in a large comprehensive care treatment program in western Kenya. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr United States. 2015;68(4):e46–55. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000000492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Braitstein P, Songok J, Vreeman RC, Wools-Kaloustian KK, Koskei P, Walusuna L, Ayaya S, Nyandiko W, Yiannoutsos C. “Wamepotea” (they have become lost): outcomes of HIV-positive and HIV-exposed children lost to follow-up from a large HIV treatment program in western Kenya. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr United States. 2011;57(3):e40–6. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3182167f0d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ochieng VO, Ochieng D, Sidle JE. Gender and Losses to Follow up From a Large HIV Treatment Program in Western Kenya. Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 2010:16. doi: 10.2471/BLT.09.064329. epub. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rachlis B, Bakoyannis G, Easterbrook P, Genberg B, Braithwaite RS, Cohen CR, Bukusi EA, Kambugu A, Bwana MB, Somi GR, Geng EH, Musick B, Yiannoutsos CT, Wools-Kaloustian K, Braitstein P. Facility-level factors influencing retention of patients in HIV care in East Africa. Facility-level factors influencing retention of patients in HIV care in East Africa. 2016 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0159994. In Press at PLoS One. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yiannoutsos CT, An MW, Frangakis CE, Musick BS, Braitstein P, Wools-Kaloustian K, Ochieng D, Martin JN, Bacon MC, Ochieng V, Kimaiyo S. Sampling-based approaches to improve estimation of mortality among patient dropouts: experience from a large PEPFAR-funded program in Western Kenya. PLoS One United States. 2008;3(12):e3843. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0003843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Geng EH, Emenyonu N, Bwana MB, Glidden DV, Martin JN. Sampling-based approach to determining outcomes of patients lost to follow-up in antiretroviral therapy scale-up programs in Africa. JAMA. United States. 2008:506–7. doi: 10.1001/jama.300.5.506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Geng EH, Bangsberg DR, Musinguzi N, Emenyonu N, Bwana MB, Yiannoutsos CT, Glidden DV, Deeks SG, Martin JN. Understanding reasons for and outcomes of patients lost to follow-up in antiretroviral therapy programs in Africa through a sampling-based approach. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr United States. 2010;53(3):405–11. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181b843f0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Egger M, Spycher BD, Sidle J, Weigel R, Geng EH, Fox MP, MacPhail P, van Cutsem G, Messou E, Wood R, Nash D, Pascoe M, Dickinson D, Etard JF, McIntyre JA, Brinkhof MW IeDEA East Africa, West Africa and Southern Africa. Correcting mortality for loss to follow-up: a nomogram applied to antiretroviral treatment programmes in sub-Saharan Africa. PLoS Med United States. 2011;8(1):e1000390. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Geng EH, Odeny TA, Lyamuya R, Nakiwogga-Muwanga A, Diero L, Bwana M, Braitstein P, Somi G, Kambugu A, Bukusi E, Wenger M, Neilands TB, Glidden DV, Wools-Kaloustian K, Yiannoutsos C, Martin J East Africa International Epidemiologic Databases to Evaluate AIDS (EA-IeDEA) Consortium. Retention in Care and Patient-Reported Reasons for Undocumented Transfer or Stopping Care Among HIV-Infected Patients on Antiretroviral Therapy in Eastern Africa: Application of a Sampling-Based Approach. Clin Infect Dis United States. 2016;62(7):935–44. doi: 10.1093/cid/civ1004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Geng EH, Odeny TA, Lyamuya RE, Nakiwogga-Muwanga A, Diero L, Bwana M, Muyindike W, Braitstein P, Somi GR, Kambugu A, Bukusi EA, Wenger M, Wools-Kaloustian KK, Glidden DV, Yiannoutsos CT, Martin JN. Estimation of mortality among HIV-infected people on antiretroviral treatment in east Africa: a sampling based approach in an observational, multisite, cohort study. The Lancet HIV. 2015;2(3):e107–e116. doi: 10.1016/S2352-3018(15)00002-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.An MW, Frangakis CE, Yiannoutsos CT. Choosing profile double-sampling designs for survival estimation with application to President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief evaluation. Stat Med England. 2014;33(12):2017–29. doi: 10.1002/sim.6087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Humphrey J, Hadi CM, Richey LE. HIV testing and re-engagement for individuals with previously diagnosed HIV Infection in New Orleans, Louisiana. AIDS Patient Care STDS. United States. 2012:509–11. doi: 10.1089/apc.2012.0120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Udeagu CC, Webster TR, Bocour A, Michel P, Shepard CW. Lost or just not following up: public health effort to re-engage HIV-infected persons lost to follow-up into HIV medical care. AIDS England. 2013;27(14):2271–9. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e328362fdde. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Buchacz K, Chen MJ, Parisi MK, Yoshida-Cervantes M, Antunez E, Delgado V, Moss NJ, Scheer S. Using HIV surveillance registry data to re-link persons to care: the RSVP Project in San Francisco. PLoS One United States. 2015;10(3):e0118923. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0118923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Byrd KK, Furtado M, Bush T, Gardner L. Evaluating patterns in retention, continuation, gaps, and re-engagement in HIV care in a Medicaid-insured population, 2006–2012, United States. AIDS Care England. 2015;27(11):1387–95. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2015.1114991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Higa DH, Crepaz N, Mullins MM Prevention Research Synthesis Project. Identifying Best Practices for Increasing Linkage to, Retention, and Re-engagement in HIV Medical Care: Findings from a Systematic Review, 1996–2014. AIDS Behav United States. 2016;20(5):951–66. doi: 10.1007/s10461-015-1204-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lubelchek RJ, Fritz ML, Finnegan KJ, Trick WE. Use of a real-time alert system to identify and re-engage lost-to-care HIV patients. JAIDS Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. LWW. 2016 doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000000973. Publish Ahead of Print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wohl AR, Dierst-Davies R, Victoroff A, James S, Bendetson J, Bailey J, Daar E, Spencer L, Kulkarni S, Pérez MJ. Implementation and Operational Research: The Navigation Program: An Intervention to Reengage Lost Patients at 7 HIV Clinics in Los Angeles County, 2012–2014. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr United States. 2016;71(2):e44–50. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000000871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tweya H, Gareta D, Chagwera F, Ben-Smith A, Mwenyemasi J, Chiputula F, Boxshall M, Weigel R, Jahn A, Hosseinipour M, Phiri S. Early active follow-up of patients on antiretroviral therapy (ART) who are lost to follow-up: the ‘Back-to-Care’ project in Lilongwe, Malawi. Trop Med Int Health England. 2010;15(Suppl 1):82–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2010.02509.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kranzer K, Govindasamy D, Ford N, Johnston V, Lawn SD. Quantifying and addressing losses along the continuum of care for people living with HIV infection in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review. J Int AIDS Soc Switzerland. 2012;15(2):17383. doi: 10.7448/IAS.15.2.17383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Marson KG, Tapia K, Kohler P, McGrath CJ, John-Stewart GC, Richardson BA, Njoroge JW, Kiarie JN, Sakr SR, Chung MH. Male, mobile, and moneyed: loss to follow-up vs. transfer of care in an urban African antiretroviral treatment clinic. PLoS One United States. 2013;8(10):e78900. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0078900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Layer EH, Brahmbhatt H, Beckham SW, Ntogwisangu J, Mwampashi A, Davis WW, Kerrigan DL, Kennedy CE. “I pray that they accept me without scolding:” experiences with disengagement and re-engagement in HIV care and treatment services in Tanzania. AIDS Patient Care STDS United States. 2014;28(9):483–8. doi: 10.1089/apc.2014.0077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rotheram-Borus MJ, Tomlinson M, Scheffler A, Le Roux IM. Re-engagement in HIV care among mothers living with HIV in South Africa over 36 months post-birth. AIDS England: LWW. 2015;29(17):2361–2362. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000000837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Camlin CS, Neilands TB, Odeny TA, Lyamuya R, Nakiwogga-Muwanga A, Diero L, Bwana M, Braitstein P, Somi G, Kambugu A, Bukusi EA, Glidden DV, Wools-Kaloustian KK, Wenger M, Geng EH East Africa International Epidemiologic Databases to Evaluate AIDS (EA-IeDEA) Consortium. Patient-reported factors associated with reengagement among HIV-infected patients disengaged from care in East Africa. AIDS. England. 2016;30(3):495–502. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000000931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gill MJ, Krentz HB. Unappreciated epidemiology: the churn effect in a regional HIV care programme. Int J STD AIDS England. 2009;20(8):540–4. doi: 10.1258/ijsa.2008.008422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Braitstein P, Katshcke A, Shen C, Sang E, Nyandiko W, Ochieng VO, Vreeman R, Yiannoutsos CT, Wools-Kaloustian K, Ayaya S. Retention of HIV-infected and HIV-exposed children in a comprehensive HIV clinical care programme in Western Kenya. Trop Med Int Health. 2010 Jul;15(7):833–41. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2010.02539.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rubin DB, Schenker N. Multiple imputation in health-care databases: an overview and some applications. Stat Med ENGLAND. 1991;10(4):585–98. doi: 10.1002/sim.4780100410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bakoyannis G, Siannis F, Touloumi G. Modelling competing risks data with missing cause of failure. Stat Med England. 2010;29(30):3172–85. doi: 10.1002/sim.4133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lee M, Dignam JJ, Han J. Multiple imputation methods for nonparametric inference on cumulative incidence with missing cause of failure. Stat Med England. 2014;33(26):4605–26. doi: 10.1002/sim.6258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Aalen OO, Johansen S. An empirical transition matrix for non-homogeneous Markov chains based on censored observations. Scandinavian Journal of Statistics. JSTOR. 1978:141–150. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pati R, Lahuerta M, Elul B, Okamura M, Fernanda Alvim M, Schackman B, Bang H, Fernandes R, Assan A, Lima J, Nash D. Factors associated with loss to clinic among HIV patients not yet known to be eligible for antiretroviral therapy (ART) in Mozambique. Journal of the International AIDS Society. 2013;16(1) doi: 10.7448/IAS.16.1.18490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Grimsrud A, Cornell M, Schomaker M, Fox MP, Orrell C, Prozesky H, Stinson K, Tanser F, Egger M, Myer L International Epidemiologic Databases to Evaluate AIDS Southern Africa Collaboration (IeDEA-SA) CD4 count at antiretroviral therapy initiation and the risk of loss to follow-up: results from a multicentre cohort study. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2015 doi: 10.1136/jech-2015-206629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gwynn RC, Fawzy A, Viho I, Wu Y, Abrams EJ, Nash D. Risk factors for loss to follow-up prior to ART initiation among patients enrolling in HIV care with CD4+ cell count ≥200 cells/μL in the multi-country MTCT-Plus Initiative. BMC Health Serv Res England. 2015;15:247. doi: 10.1186/s12913-015-0898-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.