Abstract

Background

The World Health Organization defines HIV virologic failure as two consecutive viral loads >1,000 copies/mL, measured 3–6 months apart with interval adherence support. We sought to empirically evaluate these guidelines using data from an observational cohort.

Setting

The Uganda AIDS Rural Treatment Outcomes study observed adults with HIV in southwestern Uganda from the time of antiretroviral therapy (ART) initiation, and monitored adherence with electronic pill bottles.

Methods

We included participants on ART with a detectable HIV RNA viral load and who remained on the same regimen until the subsequent measurement. We fit logistic regression models with viral resuppression as the outcome of interest, and both initial viral load level and average adherence as predictors of interest.

Results

We analyzed 139 events. Median ART duration was 0.92 years, and 100% were on a non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor-based regimen. Viral resuppression occurred in 88% of those with initial HIV RNA <1000 copies/mL and 42% if HIV RNA was >1000 copies/mL (P <0.001). Adherence after detectable viremia predicted viral resuppression for those with HIV RNA <1000 copies/mL (P = 0.011), but was not associated with resuppression for those with HIV RNA >1000 copies/mL (P = 0.894; interaction term P = 0.077).

Conclusions

Among patients on ART with detectable HIV RNA >1000 copies/mL who remain on the same regimen, only 42% resuppressed at next measurement, and there was no association between interval adherence and viral resuppression. These data support consideration of resistance testing to help guide management of virologic failure in resource-limited settings.

Keywords: HIV-1, treatment failure, viremia, medication adherence, World Health Organization, Africa South of the Sahara

INTRODUCTION

In sub-Saharan Africa (SSA), home to >70% of the global HIV disease burden 1, as many as one in three patients develop virologic failure within two years of initiating antiretroviral therapy (ART) 2. The World Health Organization (WHO) definition of virologic failure requires two consecutive HIV-1 RNA levels >1,000 copies/mL measured three months apart after a minimum six months of ART, with adherence support in the interim 3. Individuals with HIV RNA <1,000 copies/mL do not enter the WHO algorithm for treatment failure, and therefore and do not meet criteria for potentially switching to second line therapy. Guidelines also do not include recommendations for the use of resistance testing to guide therapy. Using data from a large cohort of individuals on ART in rural Uganda, we evaluated two key aspects of the WHO guidelines for managing virologic failure: 1) the threshold for defining virologic failure and 2) the relationship between level of adherence after detectable viremia and odds of resuppression.

METHODS

Setting

We analyzed data from the Uganda AIDS Rural Treatment Outcomes (UARTO) study (NCT01596322), a prospective cohort study in southwestern Uganda from 2005 to 2015, extensively described previously 4,5. The UARTO study enrolled participants at the time of ART initiation at the Mbarara Regional Referral Hospital (MRRH) Immune Suppression Syndrome (ISS) Clinic, a government-run facility that provides antiretroviral therapy at no cost to patients. Eligible participants for inclusion in the cohort were over age 18 and lived within 60 kilometers of the clinic.

Study design and study population

For this analysis, we included study participants who were 1) ART-naïve, 2) had detectable HIV RNA >400 copies/mL after a minimum of four months of ART or after a previously undetectable HIV RNA and 3) did not change regimens prior to their next HIV RNA measurement. HIV RNA was measured quarterly as part of study protocol, but results were not available to providers in real time. Participants were excluded from the analysis if adherence data was unavailable or if the time between viral load measurements was less than 30 days.

Adherence Monitoring

Adherence to ART was objectively monitored using electronic pillbox systems. MEMSCap (WestRock, Switzerland), used from 2005 to 2011, recorded pill bottle openings electronically, and data was downloaded at each study visit 6,7. Wisepill (Wisepill Technologies, South Africa), used from 2010 to 2015, transmitted pill bottle opening events over cellular networks to provide real-time adherence data 8.

Statistical analysis

Our primary outcome of interest was virologic resuppression (<400 copies/mL) at the next measurement after an initially detectable HIV RNA. HIV RNA was measured using Roche Amplicor HIV-1 Monitor Test (lower limit of detection (LLD) 400 copies/mL) from 2005 – 2012 and Cobas Taqman Test (LLD 20 copies/mL) from 2012 – 2015. We used a threshold of 400 copies/mL to consistently define the outcome throughout the study period, during which the limits of detection changed. Primary predictors of interest were 1) magnitude of initial detectable HIV RNA, categorized as: detectable <500; 500–1,000; 1,000–10,000; 10,000 to 100,000; and >100,000 copies/mL; and 2) average adherence, categorized as <70%, 70–90%, and >90%, based on prior work relating those categories with risk of subsequent viremia 9.

We used chi-squared tests to evaluate crude relationships between 1) level of HIV viremia and viral resuppression and 2) average ART adherence and viral resuppression, stratified by level of HIV viremia. We then fit logistic regression models with robust standard errors to account for repeated episodes of detectable viremia within participants. We estimated the significance of an interaction term to test associations between adherence, level of initial HIV viremia, and odds of resuppression. We also performed a secondary analysis in which viral resuppression was redefined as a second viral load <1,000 copies/mL, in fitting with the current WHO guidelines. Finally, we performed sensitivity analyses, in which we excluded repeat episodes of detectable viremia that occurred for any single individual. Statistical analysis was conducted with Stata 14 (Stata Corp, College Station, Texas, USA).

Ethics

This study was approved by Institutional Review Boards at Partners Healthcare, University of California San Francisco, Mbarara University of Science and Technology, and Uganda National Council for Science and Technology. All participants provided signed written consent.

RESULTS

We evaluated data from 107 participants (14% of total cohort) who met inclusion criteria for this analysis and contributed 139 unique treatment failure events from 2006 to 2013. Of these, 64% were women. At the time of first detectable viremia, median age was 36, median duration of ART was 0.9 years (IQR 0.7 – 2.1 years), and most participants were taking lamivudine/zidovudine/nevirapine (53%), lamivudine/stavudine/nevirapine (25%), or lamivudine/zidovudine/efavirenz (13%). (Table 1)

Table 1.

Population characteristics

| N=107 | |

|---|---|

| Age | 36 (29 – 42) |

| Male | 38 (36) |

| Duration of ART at time of failure | |

| 4–12 months | 59 (55) |

| 1–3 years | 33 (31) |

| 3–5 years | 13 (12) |

| >5 years | 2 (2) |

| ART regimen | |

| 3TC/AZT/NVP | 57 (53) |

| 3TC/AZT/EFV | 14 (13) |

| 3TC/D4T/NVP | 27 (25) |

| 3TC/TDF/EFV | 8 (7) |

| Other | 1 (1) |

| CD4 count (cells/mm3) | 275 (180 – 423) |

| Detectable HIV RNA (copies/mL) | |

| Detectable <500 | 17 (16) |

| 500 – 1,000 | 41 (38) |

| 1000 – 10,000 | 21 (20) |

| >10,000 – 100,000 | 19 (18) |

| >100,000 | 9 (8) |

Categorical data are listed as frequency (%).

Continuous variables are listed as median (IQR).

3TC = lamivudine; AZT = zidovudine; NVP = nevirapine; EFV = efavirenz; D4T = stavudine; TDF = tenofovir

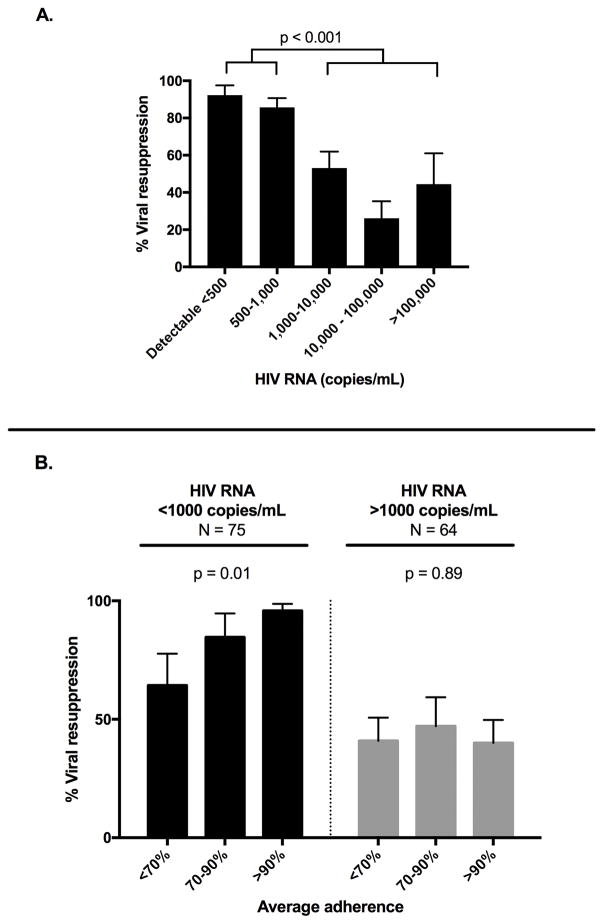

Participants with HIV RNA <1,000 copies/mL were significantly more likely to resuppress at next measurement, as compared to participants with HIV RNA >1,000 copies/mL (88% versus 42%, P < 0.001, Figure 1A). There was no significant difference in odds of resuppression between those with HIV RNA 500–1000 copies/mL, compared to HIV RNA <500 copies/mL (OR 0.5; 95% CI 0.10 – 2.60; P = 0.410).

Figure 1.

(A) Effect of initial HIV RNA level on viral resuppression to <400 copies/mL, N = 139 (B) Effect of average adherence on viral resuppression stratified by initial HIV RNA level.

For events with initial HIV RNA <1,000 copies/mL, average adherence was a significant predictor of resuppression (P = 0.011, Figure 1B). In contrast, for participants with HIV RNA >1,000 copies/mL, average adherence was not associated with resuppression (P = 0.894, Figure 1B; interaction term P = 0.077). In the secondary analysis in which viral resuppression was redefined as HIV RNA <1,000 copies/mL, rather than <400 copies/mL, only ten events were reclassified, and results remained unchanged. Results were also unchanged in sensitivity analyses when we restricted models to only first episodes of detectable viremia for each participant.

DISCUSSION

In this analysis, we used data from a longitudinal cohort in rural Uganda including objective adherence monitoring to evaluate the relationships between the level of HIV viremia, ART adherence, and viral resuppression, which are key aspects of the current WHO guidelines. We found that most of those with an HIV RNA <1,000 copies/mL (88%) resuppressed at their next HIV RNA measurement, and that adherence after the first episode of failure was a reliable predictor of resuppression. Although low-level viremia is not currently mentioned in most international guidelines, these findings suggest that such individuals should also be considered as candidates for intensified adherence support interventions. In contrast, only 42% of those with HIV RNA >1,000 copies/mL resuppressed, and higher levels of adherence did not predict resuppression in this group. Notably, resuppression rates were low even in participants with >90% average adherence, suggesting that adherence support in this group might not be sufficient to optimize rates of virologic suppression. Instead, for those with higher levels of viremia at failure, resistance testing, where feasible, may improve selection of participants for second line therapy versus adherence support interventions.

Although low-level viremia has been associated with future virologic failure 10–12; and resistance has been detected in those with HIV RNA <1000 copies/mL 13,14, our data support the current WHO recommended threshold of 1,000 copies/mL to define treatment failure. The great majority of patients below this threshold resuppressed at the next measurement. Moreover, a threshold of 1,000 copies/mL has important advantages for risk of HIV transmission 15–17 as well as accuracy of dried blood spot testing, a commonly used testing modality in the region 18–21. However, our study was relatively short in observation; and it will be important for future studies to consider long-term outcomes and rates of drug resistance for patients with low-level viremia in SSA to ensure they can achieve durable suppression on first-line regimens.

Importantly, we found low rates of resuppression (42%) for those with higher HIV RNA at time of failure, and no association between level of adherence and resuppression. These findings are in contrast to pooled estimates in a systematic review by Bonner, et al 22 which is cited by WHO as evidence to support current requirements for two consecutive HIV RNA results >1,000 copies/mL to define virologic failure, with adherence support in the interim 3. That review reported that 70% of patients with elevated HIV RNA resuppress following an adherence intervention 22. However, the review included diverse populations from multiple settings, both adults and children, varying ART regimens (including protease inhibitors), and most notably, robust adherence interventions such as educational programs, support groups, dosing diaries, and home visits, which may be feasible in some settings in SSA, but are not widely available. Moreover, even where these strategies are available, they remain largely unproven in practice 23,24.

In contrast, several other studies from sub-Saharan Africa have demonstrated that a majority (60–90%) of patients with virologic failure on first-line regimens have clinically significant drug resistance mutations at time of failure 25–28. Our results would support these studies as we found most patients do not resuppress after an HIV RNA >1,000 copies/mL, including those with >90% average adherence (Figure 1B). Similarly, a recent study in Swaziland similarly failed to find improved rates of resuppression with augmented adherence support 24. Taken together, this body of evidence suggests that resistance might be a primary driver of treatment failure for an important majority of patients with high-level viremia in the region. A clinical trial is currently underway to evaluate the feasibility, efficacy, and cost-effectiveness of resistance testing after a detectable HIV RNA with high-level viremia (NIH AI124718; NCT02787499).

Our results should be interpreted with consideration of our single site study design and sample size. Furthermore, we acknowledge that our study does not provide an exact evaluation of the WHO algorithm given that participants were included after four months of ART and that viral suppression in our study was defined as 400 copies/mL, as opposed to 1,000 copies/mL in the guidelines. We are also unable to fully evaluate the efficacy of WHO guidelines in this study given that HIV RNA testing was not done as part of routine clinical care and was not available to guide care plans or changes in therapy. We do not have paired resistance data available to assess its impact on our findings, though this is planned for future analyses. Our estimates could be biased by misestimation of ART adherence. However, we have previously demonstrated very strong associations between electronically captured adherence, drug levels and virologic failure in our study 29,30. Moreover, the only way in which misestimation of adherence would meaningfully affect our estimates would be if there was a differential practice in use (or misuse) of adherence monitors between those with high and low viral loads, which we believe to be unlikely. Approximately 75% of evaluated events in this analysis were observed on nevirapine-based regimens, which remain in wide use but are no longer a recommended first-line option in sub-Saharan Africa. Similarly, 25% of participants were on stavudine, which was no longer recommended as part of first line ART at the time the 2013 WHO guidelines were published. Because we were not powered to detect differences by regimen, future studies should attempt to do so.

In conclusion, our data support the recommended WHO HIV RNA threshold of 1,000 copies/mL to determine virologic failure. However, although patients with low-level viremia are not discussed in WHO guidelines for management of virologic failure, we offer evidence that adherence support might particularly benefit this group. In addition, because a majority of patients do not resuppress after failure with HIV RNA viremia above 1,000 copies/mL, and because adherence does not predict their resuppression, HIV drug resistance should be considered as an etiology for treatment failure so as to optimize the selection of immediate second line therapy versus adherence support in this population. In order to achieve global targets to maintain viral suppression in 90% of those on ART, feasibility of resistance testing in sub-Saharan Africa should be further evaluated.

Acknowledgments

Source of Funding: This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health [T32 AI007433-25 to S.M.M, P30 AI027763 and UM1 CA181255 to J.N.M, K23 MH099916 to M.J.S., and R01 MH054907] and the Harvard Center for AIDS Research [P30AI060354 to M.J.S]. The contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

Footnotes

S.M.M, J.E.H, J.N.M, P.W.H, V.C.M, D.R.B, and M.J.S contributed to the concept and study design. Study data was collected and managed by Y.B., N.M., J.E.H., J.N.M., P.W.H, and D.R.B. Statistical analysis was completed by S.M.M, N.M., and M.J.S. All authors contributed to manuscript production and have seen and approved the manuscript.

Meetings: Part of this data was presented at the 21st International AIDS Conference, Durban, South Africa, July 2016.

Conflicts of Interest: All authors report no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Organization WH. [Accessed July 19, 2016];Global Health Observatory Data: HIV/AIDS. 2016 http://www.who.int/gho/hiv/en/

- 2.Barth RE, van der Loeff MF, Schuurman R, Hoepelman AI, Wensing AM. Virological follow-up of adult patients in antiretroviral treatment programmes in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review. Lancet Infect Dis. 2010;10(3):155–166. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(09)70328-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Consolidated Guidelines on the Use of Antiretroviral Drugs for Treating and Preventing HIV Infection: Recommendations for a Public Health Approach. 2. Geneva: 2016. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Siedner MJ, Lankowski A, Tsai AC, et al. GPS-measured distance to clinic, but not self-reported transportation factors, are associated with missed HIV clinic visits in rural Uganda. AIDS. 2013;27(9):1503–1508. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32835fd873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Weiser SD, Tsai AC, Gupta R, et al. Food insecurity is associated with morbidity and patterns of healthcare utilization among HIV-infected individuals in a resource-poor setting. AIDS. 2012;26(1):67–75. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32834cad37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Haberer JE, Kiwanuka J, Nansera D, Ragland K, Mellins C, Bangsberg DR. Multiple measures reveal antiretroviral adherence successes and challenges in HIV-infected Ugandan children. PLoS One. 2012;7(5):e36737. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0036737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lu M, Safren SA, Skolnik PR, et al. Optimal recall period and response task for self-reported HIV medication adherence. AIDS Behav. 2008;12(1):86–94. doi: 10.1007/s10461-007-9261-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Haberer JE, Kahane J, Kigozi I, et al. Real-time adherence monitoring for HIV antiretroviral therapy. AIDS Behav. 2010;14(6):1340–1346. doi: 10.1007/s10461-010-9799-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Musinguzi N, Mocello RA, Boum Y, 2nd, et al. Duration of Viral Suppression and Risk of Rebound Viremia with First-Line Antiretroviral Therapy in Rural Uganda. AIDS Behav. 2016 doi: 10.1007/s10461-016-1447-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ryscavage P, Kelly S, Li JZ, Harrigan PR, Taiwo B. Significance and clinical management of persistent low-level viremia and very-low-level viremia in HIV-1-infected patients. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2014;58(7):3585–3598. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00076-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Laprise C, de Pokomandy A, Baril JG, Dufresne S, Trottier H. Virologic failure following persistent low-level viremia in a cohort of HIV-positive patients: results from 12 years of observation. Clin Infect Dis. 2013;57(10):1489–1496. doi: 10.1093/cid/cit529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Karlsson AC, Younger SR, Martin JN, et al. Immunologic and virologic evolution during periods of intermittent and persistent low-level viremia. AIDS. 2004;18(7):981–989. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200404300-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Taiwo B, Gallien S, Ribaudo H, Haubrich R, Kuritzkes D, Eron J. HIV drug resistance evolution during persistent near-target viral suppression. Antiretroviral Therapy. 2010;15(A38) [Google Scholar]

- 14.Labhardt ND, Bader J, Lejone TI, et al. Should viral load thresholds be lowered?: Revisiting the WHO definition for virologic failure in patients on antiretroviral therapy in resource-limited settings. Medicine (Baltimore) 2016;95(28):e3985. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000003985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Quinn TC, Wawer MJ, Sewankambo N, et al. Viral load and heterosexual transmission of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. Rakai Project Study Group. N Engl J Med. 2000;342(13):921–929. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200003303421303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Marks G, Gardner LI, Rose CE, et al. Time above 1500 copies: a viral load measure for assessing transmission risk of HIV-positive patients in care. AIDS. 2015;29(8):947–954. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000000640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fideli US, Allen SA, Musonda R, et al. Virologic and immunologic determinants of heterosexual transmission of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 in Africa. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2001;17(10):901–910. doi: 10.1089/088922201750290023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rottinghaus EK, Ugbena R, Diallo K, et al. Dried blood spot specimens are a suitable alternative sample type for HIV-1 viral load measurement and drug resistance genotyping in patients receiving first-line antiretroviral therapy. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;54(8):1187–1195. doi: 10.1093/cid/cis015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Working Group on Modelling of Antiretroviral Therapy Monitoring Strategies in Sub-Saharan A. Phillips A, Shroufi A, et al. Sustainable HIV treatment in Africa through viral-load-informed differentiated care. Nature. 2015;528(7580):S68–76. doi: 10.1038/nature16046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vojnov L. Dried blood spot samples can be used for HIV-1 viral load testing with most currently available viral load technologies: a pooled data meta-analysis and systematic review. World Health Organization Consolidated Guidelines on the Use of Antiretroviral Drugs for Treating and Preventing HIV Infection: Recommendations for a Public Health Approach Web Supplement B. 2016 [Google Scholar]

- 21.Smit PW, Sollis KA, Fiscus S, et al. Systematic review of the use of dried blood spots for monitoring HIV viral load and for early infant diagnosis. PLoS One. 2014;9(3):e86461. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0086461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bonner K, Mezochow A, Roberts T, Ford N, Cohn J. Viral load monitoring as a tool to reinforce adherence: a systematic review. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2013;64(1):74–78. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31829f05ac. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Barnighausen T, Chaiyachati K, Chimbindi N, Peoples A, Haberer J, Newell ML. Interventions to increase antiretroviral adherence in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review of evaluation studies. Lancet Infect Dis. 2011;11(12):942–951. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(11)70181-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jobanputra K, Parker LA, Azih C, et al. Factors associated with virological failure and suppression after enhanced adherence counselling, in children, adolescents and adults on antiretroviral therapy for HIV in Swaziland. PLoS One. 2015;10(2):e0116144. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0116144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wallis CL, Aga E, Ribaudo H, et al. Drug susceptibility and resistance mutations after first-line failure in resource limited settings. Clin Infect Dis. 2014;59(5):706–715. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciu314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.TenoRes Study G. Global epidemiology of drug resistance after failure of WHO recommended first-line regimens for adult HIV-1 infection: a multicentre retrospective cohort study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2016;16(5):565–575. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(15)00536-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hamers RL, Sigaloff KC, Wensing AM, et al. Patterns of HIV-1 drug resistance after first-line antiretroviral therapy (ART) failure in 6 sub-Saharan African countries: implications for second-line ART strategies. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;54(11):1660–1669. doi: 10.1093/cid/cis254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ndahimana J, Riedel DJ, Mwumvaneza M, et al. Drug resistance mutations after the first 12 months on antiretroviral therapy and determinants of virological failure in Rwanda. Trop Med Int Health. 2016;21(7):928–935. doi: 10.1111/tmi.12717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Haberer JE, Musinguzi N, Boum Y, 2nd, et al. Duration of Antiretroviral Therapy Adherence Interruption Is Associated With Risk of Virologic Rebound as Determined by Real-Time Adherence Monitoring in Rural Uganda. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2015;70(4):386–392. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000000737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Musinguzi N, Muganzi CD, Boum Y, 2nd, et al. Comparison of subjective and objective adherence measures for preexposure prophylaxis against HIV infection among serodiscordant couples in East Africa. AIDS. 2016;30(7):1121–1129. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000001024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]