Abstract

Background

Initiating antiretroviral therapy (ART) early improves clinical outcomes and prevents transmission. Guidelines for first-line therapy have changed with the availability of newer ART agents. In this study, we compared persistence and virologic response to initial ART according to the class of anchor agent used.

Setting

An observational clinical cohort study in the Southeastern United States.

Methods

All HIV-infected patients participating in the UNC Center for AIDS Research Clinical Cohort (UCHCC) and initiating ART between 1996 and 2014 were included. Separate time-to-event analyses with regimen discontinuation and virologic failure as outcomes were used, including Kaplan-Meier survival curves and adjusted Cox proportional hazards models.

Results

One thousand six hundred and twenty-four patients were included (median age of 37 years at baseline, 28% women, 60% African-American, 28% White). Eleven percent initiated INSTI, 33% NNRTI, 20% bPI, 27% Other, and 9% NRTI only regimens. Compared to non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor(NNRTI)-containing regimens, integrase strand transfer inhibitor(INSTI)-containing regimens had an adjusted hazard ratio of 0.49 (95% confidence interval, 0.35, 0.69) for discontinuation and 0.70 (95% confidence interval, 0.46, 1.06) for virologic failure. All other regimen types were associated with increased rates of discontinuation and failure compared to NNRTI.

Conclusions

Initiating ART with an INSTI-containing regimen was associated with lower rates of regimen discontinuation and virologic failure.

Keywords: HIV, antiretroviral therapy, integrase inhibitors, prospective studies, United States

Introduction

Initiating antiretroviral therapy (ART) early in HIV infection improves clinical outcomes and prevents transmission.[1,2] U.S. treatment guidelines have changed with availability of newer ART agents, and currently recommend starting ART with a combination of two nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NRTI), and an integrase strand transfer inhibitor (INSTI), or a boosted protease inhibitor (bPI).[3] The effectiveness of INSTI-containing regimens compared to previously available regimens has not been well characterized. In this study, we compared response to initial ART in the clinical setting including continuation of the initial regimen, known as persistence or durability, and virologic response.

Methods

All patients initiating ART in the University of North Carolina (UNC) Center for AIDS Research HIV Clinical Cohort, 1996-2014, were included. This prospective cohort of all primary HIV care patients at the UNC Hospitals is representative of HIV-infected patients in care in North Carolina.[4] Patients were followed from first ART initiation (baseline) until first of outcome, loss to follow-up, death or November 2015. The two primary outcomes evaluated were ART discontinuation, defined as change in anchor agent class or stopping ART for longer than 2 weeks, and virologic failure, defined as first HIV RNA level ≥400 copies/mL after 24 weeks of therapy in an intention-to-treat approach where patients lost to follow-up with HIV RNA <400 copies/mL were censored and changes in therapy were ignored. ART regimen categories were based on anchor agent: INSTI (any INSTI), bPI (ritonavir-boosted atazanavir, darunavir or lopinavir), non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor (NNRTI, efavirenz or rilpivirine), Other (including unboosted and other bPI), and NRTI (regimens including only NRTIs). Patients provided written informed consent to participate in the clinical cohort, and the UNC institutional review board approved both the cohort study and this secondary data analysis.

Separate time to event analyses were performed for each outcome of interest, including Kaplan-Meier survival curves and Cox proportional hazards models adjusted for baseline age, sex, race, CD4 cell count, HIV RNA level, and calendar year. We excluded patients missing baseline CD4 or HIV RNA measurements. In a sensitivity analysis, we included patients missing baseline measurements and used multiple imputations with Markov Chain Monte Carlo and 50 imputations based on age, sex, race, men who have sex with men (MSM) status, injection drug use (IDU), year of ART initiation, and ART regimen. We included calendar year using disjoint indicator variables for the periods 1996-2000, 2001-2005, 2006-2010, and 2011-2014. Since ART agent availability changed over time we also fit separate models for INSTI, bPI, Other and NRTI, each in comparison to NNRTI, restricting to calendar years where both ART regimen types were available, and including calendar years as a continuous variable. To account for shorter follow-up of INSTI-initiating patients, we also conducted sensitivity analyses where we restricted follow-up time for all patients to 3 years following ART initiation. For all estimates, 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) were calculated, P values were two-sided, and <0.05 was considered statistically significant. Analyses were performed in SAS software, version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Results

The 1624 patients who initiated ART between 1996 and 2014 were 28% women, 60% African-American, 28% White, and a median 37 years old at baseline (Table 1). Eleven percent initiated INSTI, 33% NNRTI, 20% bPI, 27% Other, and 9% NRTI only regimens. The most common NRTI backbone combinations were: emtricitabine/tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (FTC/TDF) among patients on INSTI (92%); FTC/TDF and zidovudine/lamivudine (ZDV/3TC) among patients on NNRTI (59% and 22%, respectively); and TDF/FTC, ZDV/3TC, and abacavir/lamivudine (ABC/3TC) among patients on bPI (57%, 18%, and 9%, respectively). Patients initiating different ART regimens differed significantly on most baseline characteristics including sex, race and year of starting ART. Notably, CD4 cell counts were statistically significantly different by ART regimen with a median of 403, 279, 230, 237, and 341 cells/mm3 for patients starting INSTI, NNRTI, bPI, Other and NRTI regimens, respectively.

Table 1. Baseline Patient Characteristics and Time to Discontinuation and Virologic Failure by Initial Antiretroviral Therapy.

| Initial ART Regimen | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||||||

| Total (n = 1624) |

INSTI (n = 173) |

NNRTI (n = 536) |

bPI (n = 331) |

Other (n = 434) |

NRTI (n = 150) |

P valuea | |

| Baseline Characteristics | |||||||

| Age y, Median (IQR) | 37 (29, 46) | 38 (26, 48) | 37 (29, 46) | 37 (29, 47) | 37 (29, 45) | 37 (31, 45) | .90 |

| Women, No (%) | 460 (28%) | 30 (17%) | 124 (23%) | 107 (32%) | 146 (34%) | 53 (35%) | <.001 |

| Raceb, No (%) | .003 | ||||||

| African-American | 979 (60%) | 109 (63%) | 328 (61%) | 174 (53%) | 268 (62%) | 100 (67%) | |

| White | 453 (28%) | 52 (30%) | 129 (24%) | 112 (34%) | 122 (28%) | 38 (25%) | |

| Other | 192 (12%) | 12 (7%) | 79 (15%) | 45 (14%) | 44 (10%) | 12 (8%) | |

| CD4 Cell Count cells/mm3, Median (IQR) | 277 (104, 463) | 403 (246, 579) | 279 (116, 468) | 230 (78, 401) | 237 (69, 442) | 341 (127, 475) | <.001 |

| HIV RNA level log10 copies/mL, Median (IQR) | 4.8 (4.2, 5.3) | 4.4 (3.9, 5.0) | 4.8 (4.2, 5.4) | 4.9 (4.3, 5.5) | 4.9 (4.2, 5.4) | 4.6 (3.9, 5.1) | <.001 |

| Calendar Year,Median (IQR) | 2005 (2000, 2010) | 2013 (2012, 2014) | 2007 (2002, 2010) | 2007 (2005, 2010) | 1999 (1998, 2003) | 1998 (1997, 2001) | <.001 |

| Follow-up years, Median (IQR)c | 5.5 (2.7, 9.7) | 2.3 (1.5, 3.1) | 5.5 (3.2, 8.8) | 5.5 (3.0, 8.7) | 6.6 (3.2, 14.2) | 9.7 (2.7, 14.7) | <.001 |

| Lost to follow-up, No (%) | 594 (37%) | 29 (17%) | 204 (38%) | 121 (37%) | 169 (39%) | 71 (47%) | <.001 |

|

| |||||||

| Time to Discontinuationd | |||||||

| Unadjusted HR single model (95% CI)e | 0.48 (0.35, 0.67) | 1 (Reference) | 1.23 (1.04, 1.46) | 1.59 (1.37, 1.85) | 3.02 (2.48, 3.68) | NA | |

| Adjusted HR single model (95% CI)e | 0.49 (0.35, 0.69) | 1 (Reference) | 1.24 (1.05, 1.47) | 1.47 (1.24, 1.75) | 3.01 (2.40, 3.78) | NA | |

| Unadjusted HR separate models (95% CI)e | 0.56 (0.40, 0.80) | 1 (Reference) | 1.28 (1.08, 1.52) | 1.58 (1.35, 1.85) | 2.61 (1.98, 3.43) | NA | |

| Adjusted HR separate models (95% CI)e | 0.52 (0.34, 0.80) | 1 (Reference) | 1.28 (1.07, 1.53) | 1.39 (1.16, 1.67) | 2.76 (2.00, 3.82) | NA | |

|

| |||||||

| Time to Virologic Failure | |||||||

| Unadjusted HR single model (95% CI)e | 0.46 (0.31, 0.67) | 1 (Reference) | 1.13 (0.92, 1.38) | 1.91 (1.61, 2.27) | 3.06 (2.46, 3.81) | NA | |

| Adjusted HR single model (95% CI)e | 0.70 (0.46, 1.06) | 1 (Reference) | 1.23 (1.00, 1.51) | 1.23 (1.02, 1.50) | 1.83 (1.44, 2.34) | NA | |

| Unadjusted HR separate models (95% CI)e | 0.74 (0.48, 1.13) | 1 (Reference) | 1.20 (0.97, 1.47) | 1.86 (1.55, 2.23) | 1.49 (1.10, 2.01) | NA | |

| Adjusted HR separate models (95% CI)e | 0.59 (0.34, 1.03) | 1 (Reference) | 1.25 (1.01, 1.55) | 1.28 (1.04, 1.57) | 1.39 (1.00, 1.94) | NA | |

Abbreviations: ART, antiretroviral therapy; INSTI, integrase strand transfer inhibitor; NNRTI, non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor; bPI, boosted protease inhibitor; NRTI, nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor; IQR, interquartile range; CI, confidence interval; NA, not applicable; HR, hazard ratio.

P values from Chi-square and Kruskal-Wallis Tests.

Race for this study was based on medical record reviews and categorized by the investigators. We assessed race in this study given prior evidence of an association with HIV clinical outcomes.

Follow-up years defined as time from ART initiation until the first of death, loss to follow-up (last clinic visit plus 12 months), or administrative censoring (November 2015).

Reasons for discontinuation included virologic failure and stopping ART for more than 2 weeks (23%, 37%, respectively) overall, and for INSTI (5%, 54%), NNRTI (18%, 42%), bPI (20%, 35%), Other (29%, 35%), NRTI (29%, 26%).

Estimates from Cox proportional hazards models. Single model estimates based on one model including all patients initiating: INSTI (raltegravir 53, dolutegravir 12, elvitegravir 108); NNRTI (efavirenz 499, rilpivirine 37); bPI (lopinavir 160, atazanavir 98, darunavir 73); Other (434); and NRTI (150). Separate model estimates based on fitting four separate models for patients initiating: (i) INSTI and NNRTI between 2007 and 2014 (raltegravir 53, dolutegravir 12, elvitegravir 108, efavirenz 240, rilpivirine 37); (ii) bPI and NNRTI between 2000 and 2014 (lopinavir 154, atazanavir 98, darunavir 73, efavirenz 467, rilpivirine 37); (iii) Other and NNRTI between 1998 and 2014 (Other 359, efavirenz 499, rilpivirine 37); and (iv) NRTI and NNRTI between 1998 and 2005 (NRTI 83, efavirenz 221). Adjusted models included age, sex, race, CD4 cell count, HIV RNA level and calendar year, all measured at ART initiation.

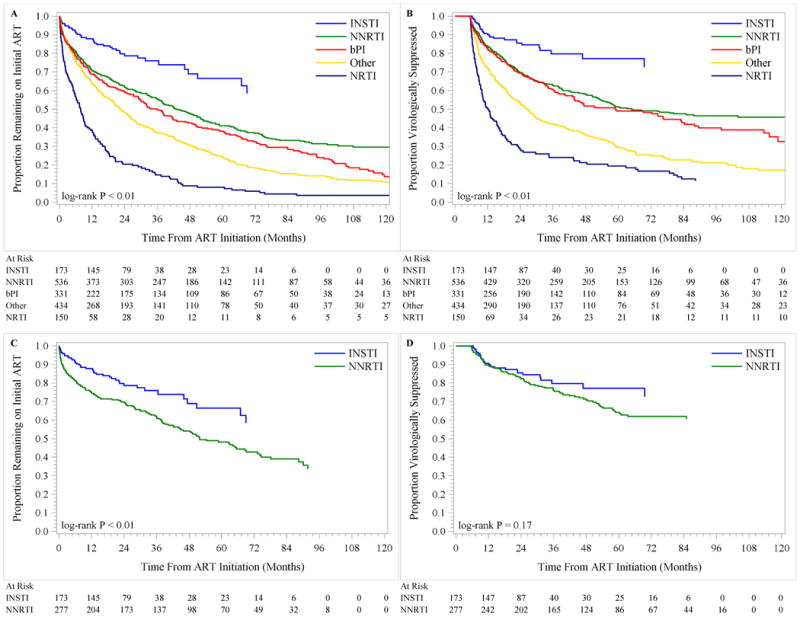

Median times to discontinuation and virologic failure for NNRTI patients were 3.5 and 5.1 years, respectively, (Figure 1A-B) compared to >7.4 years for INSTI patients for each of these events. Among 1111 patients who discontinued ART, 23% and 37% were due to virologic failure and ART interruption, respectively, and this varied by ART regimen. In unadjusted analyses, the estimated hazard ratio (HR) among those initiating an INSTI, as compared to an NNRTI, was 0.48 (95% CI, 0.35, 0.67) for time to discontinuation, and 0.46 (95% CI, 0.31, 0.67) for time to virologic failure (Table 1). After adjustment, the estimated HR for patients initiating an INSTI versus an NNRTI was 0.49 (95% CI, 0.35, 0.69) for time to discontinuation and 0.70 (95% CI, 0.46, 1.06) for time to virologic failure. When comparing only patients initiating INSTI and NNRTI regimens between 2007 and 2014, INSTI regimens still fared better (Figure 1C-D). In adjusted models restricted to years 2007-2014 and comparing only INSTI regimens to NNRTI, the HR was 0.52 (0.34, 0.80) for time to discontinuation and 0.59 (0.34, 1.03) for time to virologic failure. In this comparison, >90% of both INSTI and NNRTI regimens had TDF/FTC as the NRTI backbone. In a sensitivity analysis including patients missing CD4 and HIV RNA at baseline and using multiple imputation, in adjusted models restricted to 2007-2014 and comparing INSTI regimens (n=180) to NNRTI (n=295), the HR was 0.52 (95% CI 0.34, 0.79) for time to discontinuation, and 0.57 (0.33, 0.98) for time to virologic failure. Results were similar when follow-up was limited to 3 years after ART initiation, and when NRTI backbone was included as an adjustment variable (results not shown). Patients initiating bPI, Other or NRTI regimens fared worse in time to discontinuation and virologic failure analyses than patients initiating an NNRTI.

Figure 1. Primary End Points.

Shown are unadjusted Kaplan-Meier estimates of time to discontinuation of first antiretroviral therapy (Panel A), and time to virologic failure of initial antiretroviral therapy (Panel B), by antiretroviral therapy regimen type. Panels C and D show unadjusted Kaplan-Meier estimates of time to discontinuation and time to virologic failure, respectively, restricting to patients initiating INSTI and NNRTI regimens 2007 and later.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this study demonstrates for the first time the dramatic increase in initial therapy virologic response and persistence with INSTI-containing regimens. Studies of initial ART duration prior to the availability of INSTI agents estimated median times on first therapy ranging from 1 to 2.9 years.[5-7] More recent reports have observed increases in durability with median times from 2.9 to 4.6 years, with patients initiated on NNRTIs remaining on their initial ART longer than those started on bPIs and other agents.[8,9] In this study, patients started on non-INSTI regimens had first ART durability comparable to these prior reports with similar associations observed between NNRTI and bPI regimens. Notably we found that patients initiating INSTI-containing regimens remained on their initial regimen at least twice as long on average than patients initiating other types of ART. Our study is the first to examine specifically INSTI-containing regimens and to focus on changes of anchor class as regimen discontinuation. This definition likely reflects more relevant regimen modifications not related to simplification or to backbone agent changes.

The greater INSTI regimen persistence likely captures the contributions of favorable safety, efficacy and tolerability profiles of INSTI regimens. Randomized clinical trials of INSTI agents have reported rare drug discontinuations due to adverse events, which were generally mild or moderate and lower than for NNRTI-based regimens, as well as high virologic response rates and low failure rates that were comparable or better than NNRTI.[10-12] Our findings of INSTI effectiveness from routine clinical care therefore extend these prior results and suggest that more tolerable regimens with high efficacy result in increased initial ART persistence in a real-world setting and with longer observation.

Our findings are limited by smaller sample size and person-time available for INSTI initiators and possible residual confounding due to differences in baseline clinical covariates. In addition, specific reasons for discontinuation were not examined and may have varied across initial ART regimens. This study was also conducted at a single clinical site and therefore the generalizability of our results should be considered carefully. The demographic make-up of our clinical site is however, very similar to the demographics of the HIV epidemic in Southeastern United States.[4] Expanding these analyses to national and international cohort collaborations and including future years of INSTI clinical care experience will be important to confirm these initial findings and inform clinical care practice.

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest and Source of Funding: This study was funded by the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Center for AIDS Research (CFAR), an NIH funded program P30 AI50410. Mr. Davy-Méndez has nothing to disclose. Dr. Eron reports grants from National Institutes of Health, during the conduct of the study; personal fees from Merck, grants and personal fees from Gilead Sciences, grants and personal fees from ViiV Healthcare, grants and personal fees from Janssen, grants and personal fees from Bristol Myers Squibb, grants and personal fees from Abbvie, outside the submitted work. Ms. Zakharova has nothing to disclose. Dr. Wohl reports personal fees from Gilead Sciences, Janssen and Viiv and grants from Gilead Sciences and Merck and Co, outside the submitted work. Dr. Napravnik reports grants from NIH, during the conduct of the study.

Declaration of interests: Mr. Davy-Méndez has nothing to disclose. Dr. Eron reports grants from National Institutes of Health, during the conduct of the study; personal fees from Merck, grants and personal fees from Gilead Sciences, grants and personal fees from ViiV Healthcare, grants and personal fees from Janssen, grants and personal fees from Bristol Myers Squibb, grants and personal fees from Abbvie, outside the submitted work. Ms. Zakharova has nothing to disclose. Dr. Wohl reports personal fees from Gilead Sciences, Janssen and Viiv and grants from Gilead Sciences and Merck and Co, outside the submitted work. Dr. Napravnik reports grants from NIH, during the conduct of the study.

Funding/Support: This study was funded by the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Center for AIDS Research (CFAR), an NIH funded program P30 AI50410.

Role of the Sponsors: The sponsors had no role in the design and conduct of the study; the collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; or the preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Additional Contributions: We give special thanks to all participating patients who made this study possible.

Footnotes

Author Contributions: Davy-Méndez, Napravnik, Zakharova, Wohl, and Eron had full access to all the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Study concept and design: Acquisition of data: Davy-Méndez, Napravnik, Zakharova, Eron

Analysis and interpretation of data: Davy-Méndez, Napravnik, Wohl, Eron

Drafting of the manuscript: Davy-Méndez, Napravnik, Eron

Critical revision of the manuscript: Davy-Méndez, Napravnik, Zakharova, Wohl, Eron

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: Davy-Méndez, Napravnik, Wohl, Eron

Statistical analysis: Davy-Méndez, Napravnik

Obtained funding: Napravnik, Eron

Administrative, technical, or material support: Napravnik, Eron

Study supervision: Napravnik, Eron

References

- 1.Lundren JD, Babiker AG, Gordin F, Emery S, Grund B, Sharm S, et al. Initiation of antiretroviral therapy in early asymptomatic HIV infection. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(9):795–807. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1506816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cohen MS, Chen YQ, McCauley M, Gamble T, Hosseinipour MC, Kumarasamy N, et al. Antiretroviral therapy for the prevention of HIV-1 transmission. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(9):830–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1600693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Panel on Antiretroviral Guidelines for Adults and Adolescents. Department of Health and Human Services; [Accessed January 23, 2017]. Guidelines for the use of antiretroviral agents in HIV-1-infected adults and adolescents. Available at http://aidsinfo.nih.gov/contentfiles/lvguidelines/AdultandAdolescentGL.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Napravnik S, Eron JJ, Jr, McKaig RG, Hein AD, Menezes P, Quinlivan E. Factors associated with fewer visits for HIV primary care at a tertiary care center in the Southeastern US. AIDS Care. 2006;18:S45–50. doi: 10.1080/09540120600838928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Palella FJ, Jr, Chmiel JS, Moorman AC, Holmberg SD, HIV Outpatient Study Investigators Durability and predictors of success of highly active antiretroviral therapy for ambulatory HIV-infected patients. AIDS. 2002;16(12):1617–26. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200208160-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen RY, Westfall AO, Mugavero MJ, Cloud GA, Raper JL, Chatham AG, et al. Duration of highly active antiretroviral therapy regimens. Clin Infect Dis. 2003;37(5):714–22. doi: 10.1086/377271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Willig JH, Abroms S, Westfall AO, Routman J, Adusumilli S, Varshney M, et al. Increased regimen durability in the era of once-daily fixed-dose combination antiretroviral therapy. AIDS. 2008;22:1951–1960. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32830efd79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Abgrall S, Ingle SM, May MT, Costagliola D, Merci P, Cavassini M, et al. Durability of first ART regimen and risk factors for modification, interruption or death in HIV-positive patients starting ART in Europe and North America 2002-2009. AIDS. 2013;27(5):803–13. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32835cb997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sheth AN, Ofotokun I, Buchacz K, Armon C, Chmiel JS, Hart RL, et al. Antiretroviral regimen durability and success in treatment-naïve and treatment-experienced patients by year of treatment initiation, United States, 1996-2011. J Acqui Immune Defic Syndr. 2016;71(1):47–56. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000000813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sax PE, Wohl D, Yin MT, Post F, DeJesus E, Saag M, et al. Tenofovir alafenamide versus tenofovir disoproxil fumarate, coformulated with elvitegravir, Cobicistat, and emtricitabine, for initial treatment of HIV-1 infection: two randomised, double-blind, phase 3, non-inferiority trials. Lancet. 2015;385(9987):2606–15. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60616-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lennox JL, DeJesus E, Berger DS, Lazzarin A, Pollard RB, Ramalho Madruga JV, et al. Raltegravir versus efavirenz regimens in treatment-naïve HIV-1-infected patients: 96-week efficacy, durability, subgroup, safety, and metabolic analyses. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2010;55(1):39–48. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181da1287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Walmsley SL, Antela A, Clumeck N, Duiculescu D, Eberhard A, Gutiérrez F, et al. Dolutegravir plus abacavir-lamivudine for the treatment of HIV-1 infection. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(19):1807–1818. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1215541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]