Abstract

The purpose of this study was to formulate a dry powder for inhalation containing a combination treatment for eradication of Pseudomonas aeruginosa bacterial biofilms. Dry powders containing an antibiotic (ciprofloxacin hydrochloride, CH) and nutrient dispersion compound (glutamic acid, GA) at a ratio determined to eliminate the biofilms were generated by spray drying. Leucine was added to the spray dried formulation to aid powder flowability. A central composite design of experiments was performed to determine the effects of solution and processing parameters on powder yield and aerodynamic properties.

Combinations of CH and GA eradicated bacterial biofilms at lower antibiotic concentrations compared to CH alone. Spray dried powders were produced with yields up to 43% and mass mean aerodynamic diameters (MMAD) in the respirable range. Powder yield was primarily affected by variables that determine cyclone efficiency, i.e. atomizer and solution flow rates and solution concentration; while MMAD was mainly determined by solution concentration. Fine particle fractions (FPF) <4.46 µm and <2.82 µm of the powders ranged from 56–70% and 35–46%, respectively. This study demonstrates that dry powder aerosols containing high concentrations of a combination treatment effective against P. aeruginosa biofilms could be developed with high yield, aerodynamic properties appropriate for inhalation, and no loss of potency.

Keywords: Spray drying, ciprofloxacin, central composite design, fine particle fraction, mass median aerodynamic diameter, Pseudomonas aeruginosa

GRAPHICAL ABSTRACT

1. Introduction

Pseudomonas aeruginosa is a Gram-negative, opportunistic bacterium that forms biofilms in response to stress in people with existing disease, such as cystic fibrosis, and those that are immunocompromised. Bacterial biofilms consist of bacterial colonies surrounded by a secreted extracellular polymeric matrix. Bacteria embedded within biofilms are difficult to eradicate as they display a 100–1000 fold increase in resistance to antibiotics compared to bacteria outside a biofilm [1]. The current treatment regimen for such infections involves long-term, aggressive administration of antibiotics. However, antibiotics alone provide only temporary relief and, in many cases, recurrence of infection is observed and chronic infections [2, 3]. Thus the cost of treatment is high and the search for more effective treatment options remains ongoing [4].

A variety of methods are being pursued to promote bacterial dispersion to enhance bacterial susceptibility to antibiotics. Bacterial dispersion from a biofilm is a natural process in biofilm maturation involving active release of bacteria in reaction to environmental cues [5]. This process can also be triggered by a variety of chemical compounds, including matrix degrading enzymes, salts, chelating agents, surfactants, and nutrients [6–11]. Nutrient compounds, such as glucose, amino acids, and organic acids, show promise as dispersion-causing agents that could be inexpensively added to existing treatments [7, 11]. Nutrient compounds create a high nutrient concentration external to the biofilm, causing bacterial movement from the biofilm to the surrounding environment via chemotaxis [5]. The dispersed bacteria display phenotypic characteristics of planktonic bacteria [7], suggesting they may exhibit higher susceptibility to antibiotics. Indeed, we recently demonstrated that dispersed bacteria are not only more susceptible to antibiotics, but that biofilms grown in vitro can be eradicated with lower antibiotic concentrations when combined with nutrient dispersion compounds [12].

The objective of the current study was to formulate a dry powder for delivery of both antibiotics and nutrient dispersion compounds in a single aerosol via inhalation. Dry powder aerosols provide advantages over other formulations, including delivery of the therapeutic dose directly to the site of infection, which cannot be achieved with oral or IV administration, and faster administration time, portability, and simpler cleaning requirements compared to nebulization [13, 14]. Due to these advantages, antibiotic-containing dry powder aerosols are currently used in the treatment of infections in CF and can offer improved patient compliance [15, 16]. Here, we aimed to develop a dry powder aerosol with high yield and good aerodynamic properties for lung deposition of combination treatments containing antibiotics and dispersion compounds. We used design of experiments to optimize formulation parameters (solution pH, solution concentration, inlet temperature, atomizer flow rate, and solution flow rate) to achieve these properties.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

Ciprofloxacin hydrochloride (CH), a broad-spectrum, fluoroquinolone antibiotic used clinically against P. aeruginosa infections, was purchased from MP Biomedicals LLC (Solon, OH). L-glutamic acid (GA, a nutrient dispersion compound), L-leucine (an excipient to enhance powder flowability), silicone oil DC 200, and hexane mixture of isomers reagent 98.5% were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). Hydrochloric acid was purchased from VWR (West Chester, PA). Sodium hydroxide was purchased from Fisher Scientific (Fair Lawn, NJ). Purified water was obtained from a NanoPure Infinity Ultrapure Water System (Barnstead Int., Dubuque, IA).

2.2. Treatment of Bacterial Biofilms to Identify Combination Concentrations

P. aeruginosa mucoid lab strain PAO1 (ATCC, Manassas, VA), a common laboratory strain, was chosen as the test strain [17]. A bacterial suspension of PAO1 containing 1.5×107 CFU/mL of bacteria was prepared in Mueller Hinton Broth (MHB). Biofilms were grown by adding the suspension to a Minimum Biofilm Eradication Concentration (MBEC)™ assay trough (Innovotech, Edmonton, Alberta, Canada), placing the peg lid on the trough such that the 96 pegs dip in the suspension, and incubating the trough at 37°C for 24 hrs [18] on a rocker table.

Grown biofilms were then treated with combinations of CH and GA. Biofilms grown on the pegs were treated by dipping the pegs in wells of a 96-well plate containing either CH alone across antibiotic concentrations from 1 µg/mL to 1000 µg/mL, or a combination of CH at various concentrations and 20 mM GA at 37°C for 24 hrs. Post-treatment, the peg lid with the residual biofilms was transferred to 96-well plate containing sterile MHB. The biofilms were dispersed in the media by sonicating the plate in a sonic water bath. The peg lid was then discarded and the 96-well plate was incubated at 37°C for 24 hrs. Optical density (OD) of the bacterial suspensions was measured at 650 nm to obtain suspension turbidity, with a limit of quantification at an OD of 0.1. Greater turbidity (higher OD) was indicative of greater total bacterial count. Sterile MHB was used as the negative control. OD is reported as the average ± standard deviation. Student’s t-test was used to determine statistically significant differences between treatments, with p<0.05 signifying statistical significance.

To further quantify the variability with a single treatment across multiple biofilm samples, the incidence of growth (IOG) was determined. IOG is defined as the percentage of wells with an optical density greater than 0.1 at 650 nm (the limit of detection of the assay). Wells with OD650nm below 0.1 represented ‘no measurable growth’, while wells with OD650nm above 0.1 represented ‘measurable growth’. IOG was calculated using the OD readings obtained for the post-treatment residual biofilms by taking the ratio of the number of wells for a particular treatment that gave an OD650nm greater than 0.1 to the total number of wells for that treatment.

2.3. Formulation of Dry Powders via Spray Drying

A Buchi 190 spray drier (Flawil, Switzerland) was used to generate dry powder aerosols containing CH, GA, and leucine. Leucine is a commonly used excipient that reduces adhesion between particles and improves the flowability of powders [19, 20]. Previous work in our laboratory found that as little as 10 wt% leucine could be incorporated into the dry powders to improve powder dispersion and deposition [21]. An aqueous solution containing 10% leucine, 1.5% CH, and 88.5% GA (CH:GA ratio determined from OD experiments to eradicate biofilms) at room temperature was pumped into the spray dryer using a MasterFlex L/S peristaltic pump equipped with an Easy-Load II head and size 16 platinum-cured silicone tubing (Cole-Parmer, Vernon Hills, IL) and spray dried at an aspirator pressure of −30 mbar.

A central composite design of experiments was used to investigate the effects of formulation parameters and spray dryer processing parameters on the yield and aerodynamic properties of the generated dry powders. Solution pH (3–11), solids concentration of the spray dried solution (0.025–0.725 wt %), spray dryer inlet temperature (155–195°C), atomizer air flow rate (150–750 L/hr), and solution flow rate (5–13 mL/min) were varied (Table 1, factor values for all 32 runs in the central composite design are provided in the supplementary data). Solution pH was included as changes to the ionizable groups have been previously observed to affect particle morphology and amino acid crystallinity during spray drying [22, 23]. Solids concentration has been observed to significantly affect yield and moisture content of spray dried powders [21, 24, 25]. Inlet temperature alters the drying time of the aerosols, thereby potentially affecting final powder porosity and morphology [25]. The minimum inlet temperature was selected to prevent accumulation of water in the collection chamber under typical parameter settings (determined by spray drying water alone). The maximum temperature chosen was the maximum allowed by the Buchi spray dryer. The range for atomizer air flow rate was determined by the minimum and maximum allowable rates on the spray dryer. Reducing solution flow rate has been found to considerably increase yields, while higher flow rates are associated with greater moisture content in the powders due to improper evaporation of the solvent [21, 24]. The experiments were designed and analyzed using Statgraphics® (Warrenton, VA). Analysis of variance (ANOVA) was performed to determine the effect of each factor on individual responses.

Table 1.

Independent variables and their respective levels in the central composite design.

| Design Point | pH | Solution Concentration, wt% |

Inlet Temperature, °C |

Atomizer Rate, L/hr |

Solution Flow Rate, mL/min |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Axial | 3 | 0.025 | 155 | 150 | 5 |

| Cubic | 5 | 0.200 | 165 | 300 | 7 |

| Midpoint | 7 | 0.375 | 175 | 450 | 9 |

| Cubic | 9 | 0.550 | 185 | 600 | 11 |

| Axial | 11 | 0.725 | 195 | 750 | 13 |

2.4. SEM Imaging

Powder was tapped onto double-sided carbon tape on an aluminum stub using a spatula and excess powder tapped off the stub. The sample was sputter coated (Emitech K550 sputter coater, Kent, England) with gold and palladium for three minutes to prevent charging of the powder during imaging. The samples were visualized with the Hitachi S-4800 SEM (Krefeld, Germany) with an accelerating voltage of 2 kV and a working distance of 5 µm, and images taken.

2.5. Aerodynamic Properties of Dry Powder Aerosols

The Next Generation Impactor (NGI, MSP Corporation, Shoreview, MN) was used to separate the dry aerosol particles into size fractions (cutoff diameters of 8.06 µm, 4.46 µm, 2.82 µm, 1.66 µm, 0.94 µm, 0.55 µm, and 0.34 µm for stages 1 to 7). The eight trays of the NGI were coated with a 3% solution of silicone oil in hexanes to prevent reentrainment of particles and dried for 24 hrs at room temperature in a fume hood. The NGI was assembled with the trays, NGI induction port, mouthpiece adaptor, HCP5 vacuum pump, flow meter (DFM 2000), and critical flow controller (TPK 2000, Copley Scientific, Nottingham, UK). A size 3 gelatin capsule was filled ½–⅔ full (~10–80 mg, depending on powder volume) with powder and placed in a low-resistance inhaler device, the Aerolizer® (Novartis Pharma AG, Basel, Switzerland). The inhaler was placed into the mouthpiece adaptor and the capsule punctured. The critical flow controller was set to pull powder in at 60 L/min for 4 sec. Powder deposited on each stage was collected using purified water and the UV absorbance of each solution measured at 276 nm using SpectraMax Plus 384 plate scanner (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA) to quantify the amount of ciprofloxacin deposited on each stage. The mass mean aerodynamic diameter and geometric standard deviation (GSD) were determined from the cumulative mass distribution curve using the Copley Citdas software (Copley Scientific, Nottingham, UK). For bimodal size distributions, a two log normal mode algorithm coded in MatLab was applied to the data to quantify the MMAD and GSD for each mode independently [26]. Emitted fraction for each powder was calculated by dividing the amount of powder aerosolized from the inhaler by the total powder loaded in the capsule. The fine particle fraction less than 4.46 µm (FPF< 4.46 µm), the fraction of particles depositing on stages 3 and below in the NGI, and fine particle fraction less than 2.82 µm (FPF< 2.82 µm), the fraction of particles depositing on stages 4 and below in the NGI, were determined using the Copley Citdas software.

The NGI is designed to operate at any flow rate between 30 and 100 L/min, though 60 L/min was chosen as peak performance could be expected from the device at this flow rate. The Aerolizer device delivers a more uniform dose at inspiratory flow rates of 60 L/min (~90–100%,) whereas at lower flow rates (30 L/min) the uniformity decreases to 80% of the label claim for marketed formulations [27]. A variety of studies have concluded that the majority of CF patients can achieve the flow rates required for efficient aerosol dispersion from dry powder inhalers. With low resistance devices such as the Aerolizer, 96% of patients (out of 96 patients from ages 6 to 54) were able to attain a flow rate of 60 L/min [28, 29].

2.6 Potency of Spray Dried Powders Compared to Raw Materials

To measure the effect of spray drying on the potency of the combination powder, MBEC values were determined for solutions containing the spray dried powder and raw CH and GA. Briefly, the spray dried powder (158 mg) was dissolved in 10 mL sterile MHB and serially diluted to obtain a total mass of CH and GA of 12 to 3000 µg. Solutions were prepared from raw CH and GA to contain the same concentrations as the solutions containing the spray dried formulation. PAO1 biofilms were grown in the MBEC assay trough as described in Section 2.2. The biofilms were treated for 24 h with solutions made from either the raw materials or spray dried powder. Then the residual biofilms on the pegs were dispersed in sterile MHB and incubated for 24 h, and the optical density of each solution was measured at 650 nm.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Impact of Combination Treatments Against P. aeruginosa Bacterial Biofilms

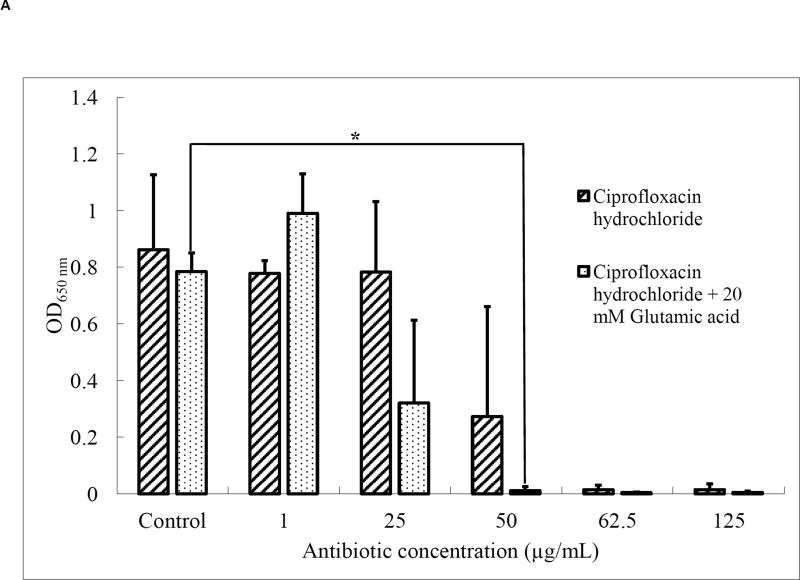

The ratio of ciprofloxacin (CH) to glutamic acid (GA) required for treatment of P. aeruginosa bacterial biofilms was determined prior to aerosol formulation. Upon treatment with ciprofloxacin (CH) alone, the total bacterial cell density, as measured by optical density, was significantly reduced at antibiotic concentrations of 50 µg/mL and higher (Fig. 1A), with a complete loss of bacterial viability at a concentration of 62.5 µg/mL. When the antibiotic treatment was combined with 20 mM glutamic acid (GA), total bacterial counts were reduced at a lower antibiotic concentration of 25 µg/mL, with a complete loss of bacterial viability at 50 µg/mL. Thus, combining a nutrient dispersion compound with the antibiotic enabled bacterial elimination at lower antibiotic concentrations. Sauer et al. previously demonstrated that GA chemotactically attracts P. aeruginosa out of biofilms at concentrations of 18 mM and higher [7]. Thus, the 20 mM GA concentration used here is expected to have resulted in a higher number of bacteria released from the biofilm, thus enhancing their susceptibility.

Fig. 1.

(A) Optical density at 650 nm (n=4; *p < 0.05) and (B) incidence of growth (n=4) of residual P. aeruginosa PAO1 biofilms after treatment with CH or a combination of CH and 20 mM GA.

Similarly, the incidence of growth (IOG) was reduced to 75% (i.e. 3 in 4 treated biofilms regrew after treatment) at an antibiotic concentration of 50 µg/mL. No regrowth was observed in any samples at an antibiotic concentration of 62.5 µg/mL (Fig. 1B). The combination of antibiotic with 20 mM GA resulted in a decrease in regrowth by 50% at a lower antibiotic concentration (25 µg/mL), and no regrowth was observed in any samples at antibiotic concentrations of 50 µg/mL and higher. This confirmed that the combination treatment caused better eradication of the biofilm bacteria at lower antibiotic concentrations compared to the antibiotic alone. Based on these results, we developed dry powder aerosols with a mass ratio of antibiotic:dispersion compound of 2.2:97.8 (equivalent to 50 µg/mL CH and 20 mM GA).

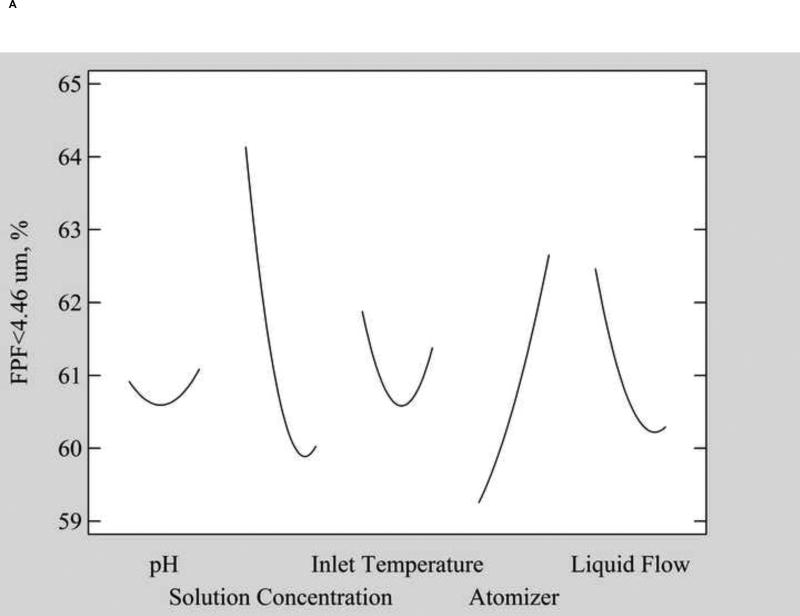

3.2. Central Composite Design

Statistical results of the design of experiments studies are provided in Table 2 (responses for all 32 runs of the central composite design are provided in the supplementary material). Two runs did not produce powder for analysis. Water collected in the product vessel during Run 6, which had the lowest atomizer rate of 150 L/hr. In Run 11, which had the lowest solution concentration of 0.025 wt %, only a few, large, agglomerated particles were collected.

Table 2.

Summary of effects of powder preparation parameters on important powder yield and aerodynamic properties.

| Input variables (range) |

Effect on yield Significance (range) |

Effect on Ave. MMAD Significance (range) |

Effect on MMAD1 Significance (range) |

Effect on MMAD2 Significance (range) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| pH (3–11) | p = 0.11 (not sig.) (25.0–28.0%) | p = 0.69 (not sig.) (3.56–3.52 µm) | p = 0.92 (not sig.) (1.05–1.02 µm) | p = 0.16 (not sig.) (4.64–4.8 µm) |

| Solution conc. (0.025–0.725 wt%) | p < 0.003 (23.0–32.0%) | p < 0.03 (3.31–3.63 µm) | p = 0.89 (not sig.) (0.97–1.05 µm) | p < 0.003 (4.30–4.85 µm) |

| Inlet temperature (155–195°C) | p = 0.25 (not sign.) (28.0–25.5%) | p = 0.58 (not sig.) (3.47–3.58 µm) | p = 0.83 (not sig.) (1.03–1.11 µm) | p = 0.59 (not sig.) (4.77–4.67 µm) |

| Atomizer rate (150–750 L/hr) | p < 0.001 (11.5–29.5%) | p = 0.30 (not sig.) (3.59–3.46 µm) | p = 0.17 (not sig.) (1.24–0.83 µm) | p = 0.08 (not sig.) (4.83–4.60 µm) |

| Solution flow rate (5–13 mL/min) | p < 0.02 (25.0–28.0%) | p = 0.25 (not sig.) (3.45–3.58 µm) | p = 0.375 (not sig.) (1.24–1.01 µm) | p < 0.03 (4.56–4.83 µm) |

| Input variables (range) |

Effect on EF Significance (range) |

Effect on FPF<4.46 µm Significance (range) |

Effect on FPF<2.82 µm Significance (range) |

|---|---|---|---|

| pH (3–11) | p = 0.06 (not sig.) (89.5–73.5%) | p = 0.91 (not sig.) (60.6–61.1%) | p = 0.50 (not sig.) (39.3–40.3%) |

| Solution conc. (0.025–0.725 wt%) | p = 0.60 (not sig.) (82.0–87.5%) | p < 0.04 (64.2–59.8%) | p = 0.07 (not sig.) (42.3–38.7%) |

| Inlet temperature (155–195°C) | p = 0.39 (not sig.) (90.0–83.0%) | p = 0.73 (not sig.) (61.8–60.6%) | p = 1.00 (not sig.) (39.5–40.2%) |

| Atomizer rate (150–750 L/hr) | p = 0.07 (not sig.) (71.5–91.0%) | p = 0.08 (not sig.) (59.2–62.6%) | p = 0.50 (not sig.) (39.0–40.2%) |

| Solution flow rate (5–13 mL/min) | p = 0.88 (not sig.) (86.0–84.0%) | p = 0.16 (not sig.) (62.4–60.2%) | p = 0.27 (not sig.) (40.9–39.1%) |

p-values < 0.05 are statistically significant.

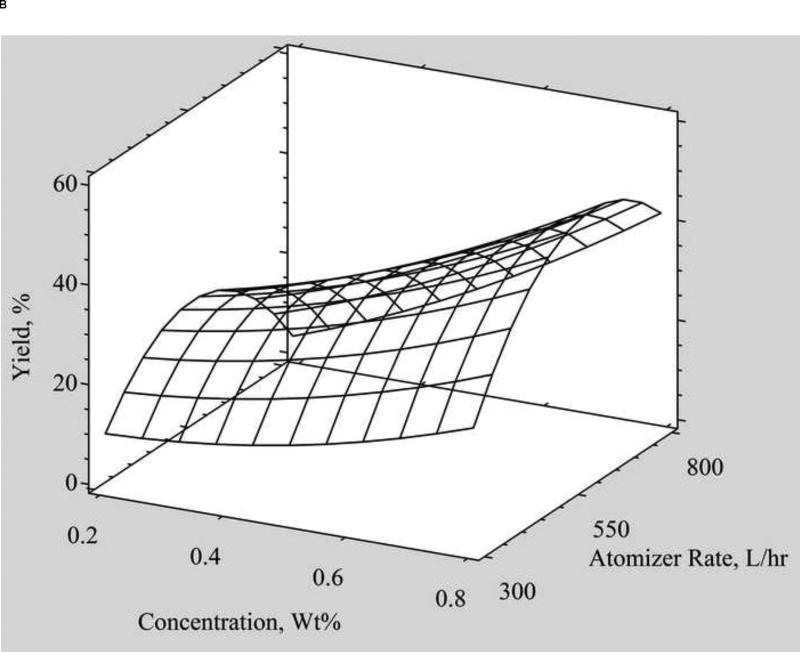

3.2.1. Product Yield

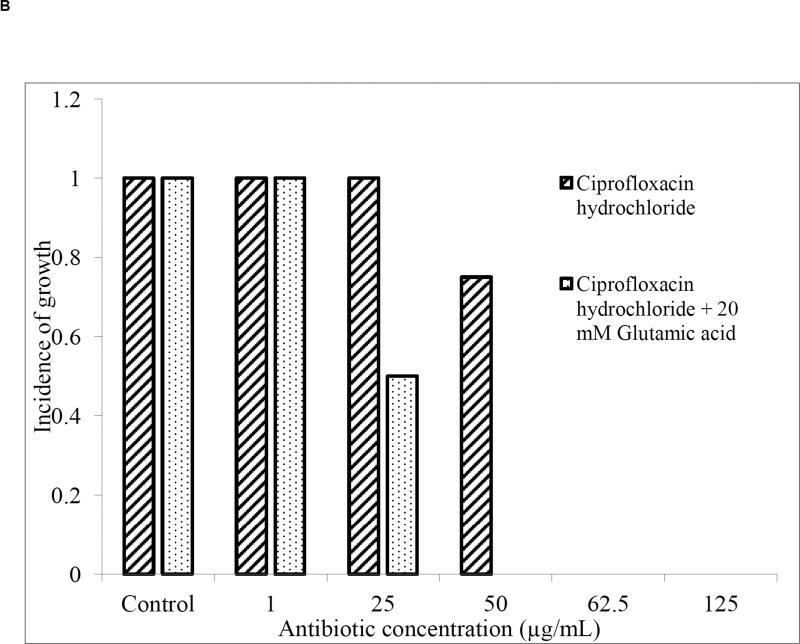

Powders generated by spray drying combinations of leucine, CH, and GA were produced with yields ranging from 6.0% to 43.1%. Bench top spray dryers, such as the Buchi spray dryer used in this study, typically produce powders at yields less than 90% due to losses as powder sticks to the large drying chamber prior to any collection and reported yields range widely (e.g. 8% to 84%[19, 30–32]. In this study, 3 of the 5 input variables significantly impacted the product yield. Increasing the solution concentration, atomizer air flow rate, and liquid flow rate significantly increased the yield of the dry powder collected (Table 2). An increase in solution concentration from 0.025 to 0.725 wt % resulted in a 40% increase in yield (Fig. 2). The impact of solution concentration on yield is a consistent trend found in literature [21, 25, 30, 32, 33], as a higher solution concentration results in larger particle formation and thus better collection of particles by the spray dryer cyclone [34]. Increasing the atomizer air flow rate from 150 to 600 L/hr resulted in a 160% increase in yield (Fig. 2B). The increase in yield with atomizer air flow rate is consistent with previous studies of spray dried polymeric nanocapsules and co-spray dried theophylline and hydroxypropyl methylcellulose [32, 35]. Increasing the atomizer air flow rate has two main effects on spray drying: first it results in the formation of smaller droplets, which would tend to decrease yield, but also enhances the action of the cyclone, leading to more efficient collection [34]. At atomizer air flow rates above 600 L/hr, the yield decreased. At very high atomizer air flow rates, above 600 L/hr in this study, powder is likely blown out of the collection vessel and removed via the exhaust. Yield was maximized at an atomizer flow rate of about 600 L/hr and the highest solution concentration of 0.725 wt%.

Fig. 2.

A) Main effects plot showing the mean response of each formulation and process parameter on yield. B) Surface plot showing the effect of atomizer air flow rate and solution concentration on the percent yield.

3.2.2. Mass Median Aerodynamic Diameter (MMAD)

Aerodynamic particle size is a key formulation parameter that determines the probability of an aerosol particle depositing within the respiratory tract [36]. Its value depends on the geometric size and density of the particle, both of which can be manipulated to achieve a desired aerodynamic size. In general, particles with smaller aerodynamic diameters penetrate deeper into the respiratory tract. Most particles >5 µm in diameter are considered too large for pulmonary deposition as they impact on the oropharynx and in the first airway bifurcation [37, 38]. Particles in the 3 to 6 µm aerodynamic diameter range preferentially deposit in the large conducting airways and those 1 to 3 µm deposit largely in the small airways and alveoli. The optimal aerodynamic particle size range for deposition within the lung is about 1–5 µm. Optimally, the aerodynamic size of an aerosolizable powder would be tuned to the location of the disease [39]. For P. aeruginosa infections, preserved lung tissue from CF patients colonized with P. aeruginosa prior to antibiotic treatment showed colonization in the tracheobronchial regions of the lungs. After aggressive antibiotic therapy, lung explants from patients showed P. aeruginosa colonization in the alveolar region of the lungs.[40] Therefore, when antibiotics are not effective at eradicating all bacteria in the conducting airways, the bacteria relocate to the respiratory airways. For effective treatment of P. aeruginosa infections, treatment of early acute infections may be focused solely on the conducting airways. But chronic infections may require achieving high drug concentrations across both the conducting and respiratory zones, thus the 1–5 µm range is most appropriate for this application.

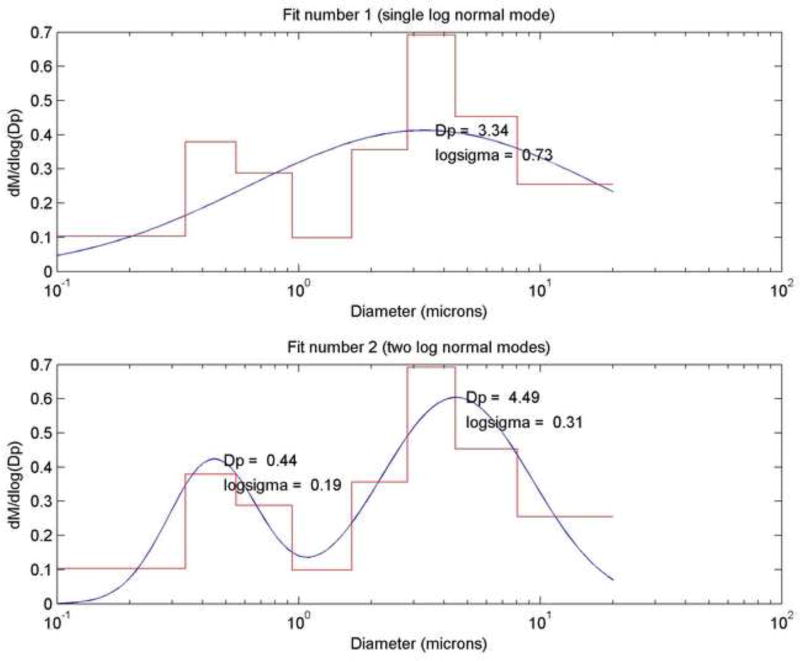

The mass median aerodynamic diameter of the powders, the diameter at which 50% of the particles by mass are larger and 50% are smaller, was estimated by impaction [36] using a Next Generation Impactor. Figure 3 (top) depicts a typical size distribution acquired from the impactor software, which assumes a single log normal distribution. From this distribution, a single MMAD value of 3.34 µm is calculated. However, in these studies bimodal particle distributions were observed in the cumulative mass distribution curves, which was verified by SEM imaging (Fig. 4). Thus the single log normal mode fit did not match the data well and we applied a two log normal mode fit to the experimental data (Fig. 3) [26]. Figure 3 (bottom) presents the resulting fit and the MMAD (Dp on the graph) for each mode (minor mode, MMAD1 = 0.44 µm; major mode, MMAD2 = 4.49 µm). The bimodal particle distribution is likely due to unsteady solution flow from the peristaltic pump into the spray dryer. Other researchers formulating with leucine have reported multiple particle sizes in the resulting spray dried aerosols [19, 30, 33, 41], though typically a single MMAD is reported. To enable comparison to previous literature studies, we report the single MMAD value obtained from the Citidas software, but also report results from the two log normal mode fit to better represent the size data for powders generated.

Fig. 3.

Frequency particle size distribution curves: (Top) single log normal mode fit to the size distribution, with MMAD (Dp) of 3.34 µm and GSD (logsigma) of 0.73 matching the values calculated by the Copley Citdas software, and (Bottom) two log normal modes fit to the size distribution providing MMAD and GSD values for each mode.

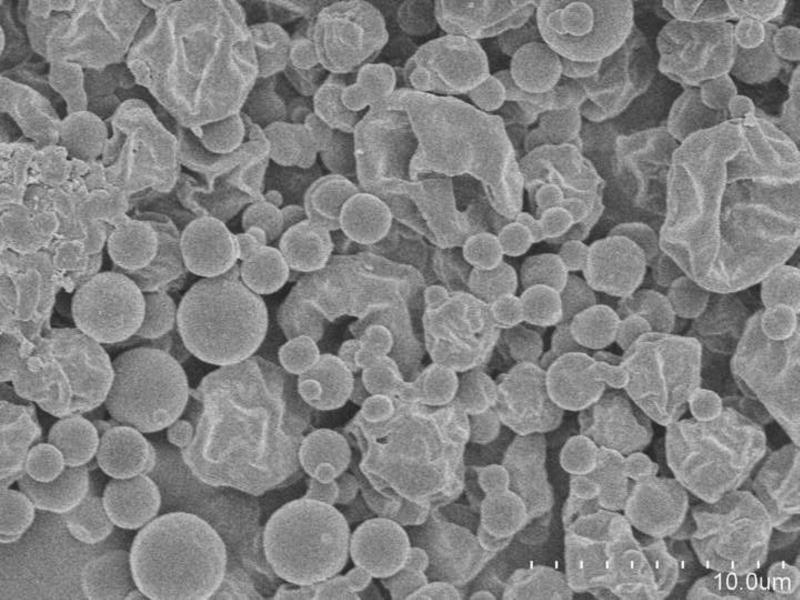

Fig. 4.

SEM image of spray dried powder (Run 24) in which two populations of particles, small spherical particles and larger wrinkled particles, were observed. Scale bar = 10 µm.

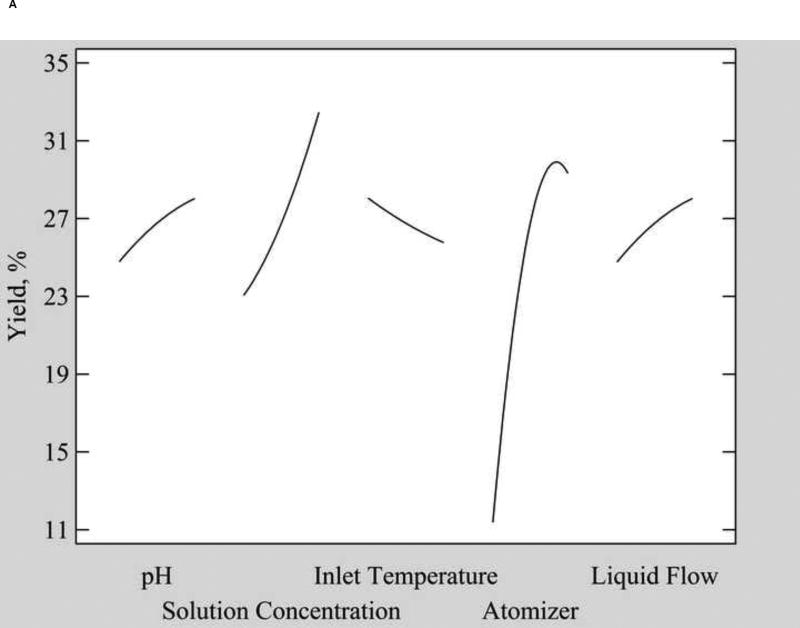

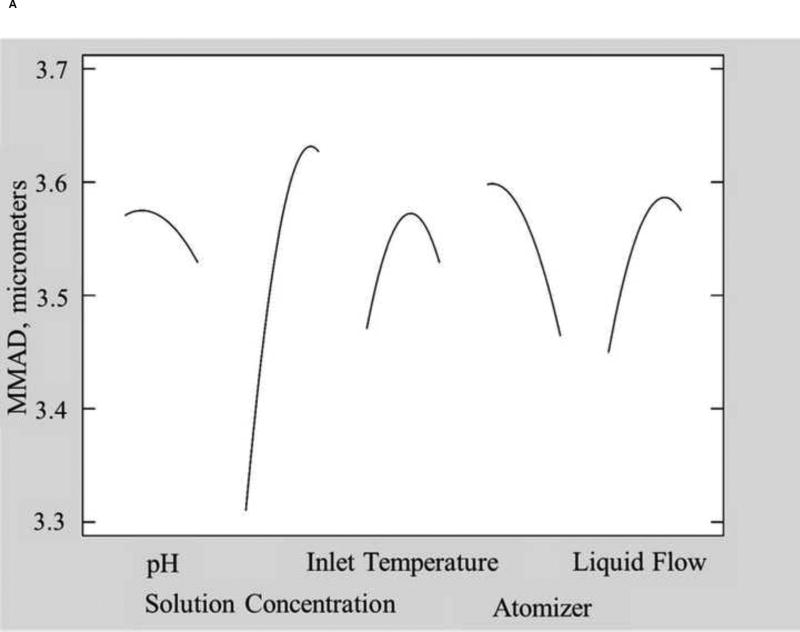

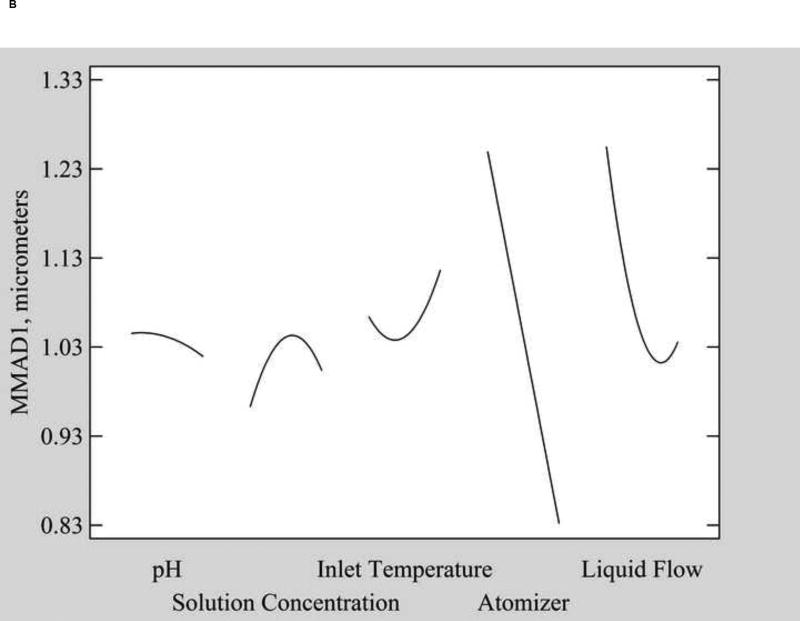

The single mode MMAD values ranged from 2.9 µm to 5.0 µm (data provided in the supplementary material), within the typical range reported for spray dried formulations containing leucine [19, 30, 41–43]. Fig. 5A shows the main effects of each factors on the single mode MMAD. Only solution concentration significantly affected MMAD (p=0.027). Increasing the concentration of the solution being atomized results in droplets that contain more solid material, resulting in either a higher density of the particles or larger particle size upon drying due to crust formation at the surface as the surface concentration increases [21, 32–34].

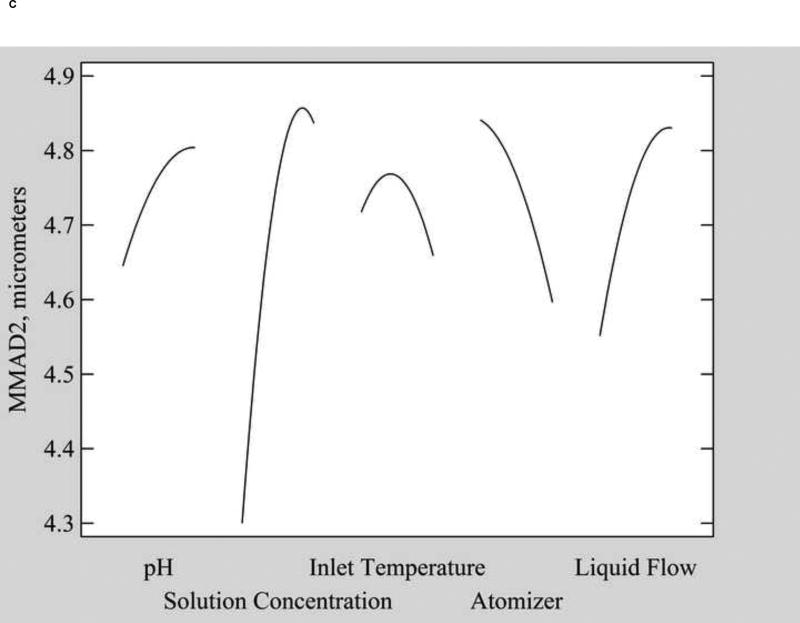

Fig. 5.

Main effect plots of A) MMAD from the single log normal mode fit, B) MMAD1, the minor mode from the two log normal mode fit, and C) MMAD2, the major mode from the two log normal mode fit.

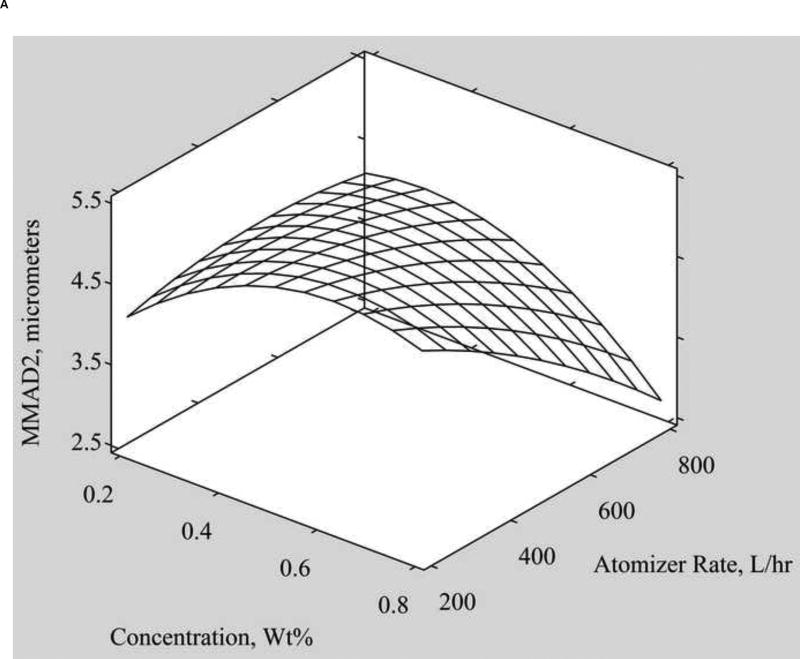

Using the two log normal mode distribution fit, two MMAD modes were observed and the impact of factors on each mode individually was evaluated. The MMAD of the minor mode (MMAD1) ranged from 0.4 µm to 1.8 µm for different powder formulations and was not significantly affected by any factor (Table 2). However, MMAD2, which ranged from 2.8 µm to 5.1 µm, was affected by numerous factors (Fig. 5C). Similar to the single mode MMAD, an increase in solution concentration significantly increased MMAD2 (p=0.002), likely due to the dominance of this second mode in the overall volume diameter distribution. In addition, a second variable, liquid flow rate (p=0.026), affected MMAD2. Increasing the liquid flow rate prolongs the drying time for droplets and decreases the outlet temperature, which can result in enhanced collisions and agglomeration of drying droplets (leading to larger particle size) or a higher residual water content in the powders (leading to higher density) [33].

Significant two-way interactions on MMAD2 were observed between solution concentration and atomizer rate (p=0.023), as well as inlet temperature and atomizer rate (p=0.035). A larger MMAD2 was achieved with a high solution concentration and low atomizer rate. Together these two parameters produce large droplets with a high solids concentration, both resulting in larger MMAD [32, 34]. A significant interaction between inlet temperature and atomizer air flow rate on particle size is anticipated as both enhance the energy for the drying process [31]. The effects of inlet temperature and atomizer air flow rate balance each other, such that a ridge can be observed in the surface response plot (Figure 6B). Increasing the atomizer air flow rate increases the energy supplied for breaking up the liquid into droplets, thus generating smaller droplets. Inlet temperature has the opposite effect, where increasing inlet temperature increases particle size. Thus to achieve smaller particle aerodynamic sizes (< 3 µm), powders can be spray dried using either a low inlet temperature and high atomizer flow rate or a high temperature and low atomizer flow rate.

Fig. 6.

Surface response plots of the effects of A) solution concentration and atomizer rate and B) inlet temperature and atomizer rate on MMAD2.

Geometric standard deviation (GSD) represents the spread or polydispersity of the size distribution, thus a value of 1 is truly monodisperse. Practically, GSD values less than 1.2 are regarded as monodisperse [44]. Average GSD values for the minor mode (GSD1) ranged from 1.5 to 14.0, indicating high polydispersity in this mode. Average GSD values for the major mode (GSD2) were smaller, ranging from 0.7 to 2.8. The regional deposition of aerosol particles in the lungs can be controlled by tailoring the polydispersity of particles, when combined with proper breathing parameters [45]. Monodisperse aerosols may be desirable for better predictability in the deposition profile. However, polydisperse aerosols may enable more distributed deposition across the lung spaces and, with the right breathing pattern, can achieve targeting of the lung periphery [45, 46].

3.2.3. Emitted Fraction

Emitted fraction (EF) is the fraction of the powder loaded in the capsule that was aerosolized from the inhaler and represents the efficiency of aerosolization of the powder [47]. Higher emitted fractions lead to greater amount of drug entering the lungs and improved efficacy. Variations in the EF values could lead to variations in the clinical response [48]. EF values in the current study ranged from 45.55 to 98.09%, though none of the parameters significantly affected the emitted fraction of the aerosolized powders. The wide range of EF values is likely due to differences in powder dispersion based on capsule loading, which was based on powder volume, and particle surface properties, which impact powder cohesion [14].

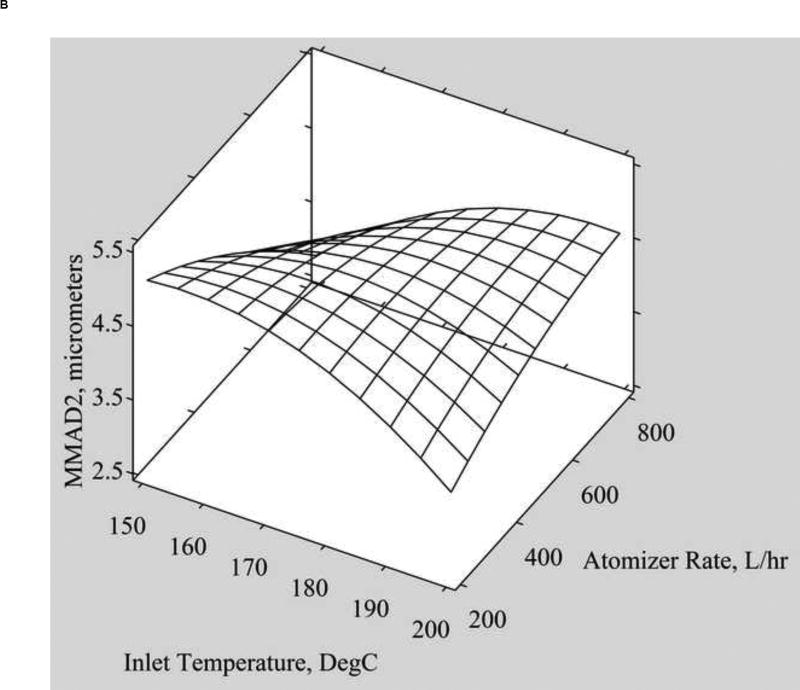

3.2.4. Fine Particle Fractions (FPF)

Historically, the optimal aerodynamic particle size range for deposition in the lung was deemed to be <5 µm, though there is some evidence that impactor data based on particles <3.5 µm may more accurately predict total in vivo deposition [38, 49]. Thus in these studies we evaluated fine particle fractions less than both of these diameters. To eliminate errors due to interpolation, fine particle fractions were evaluated at impactor cutoffs that were closest to the desired size, that is fine particle fractions less than 4.46 µm (FPF<4.46 µm) and 2.82 µm (FPF<2.82 µm).

The average FPF<4.46 µm and FPF<2.82 µm for spray dried powders produced in this study ranged from 56 to 70% and 35 to 46%, respectively, indicating the powders could achieve substantial deposition in the lungs. Similar FPF values have been observed with spray dried formulations containing only the amino acid leucine [30]. Leucine modulates the aerosolization behavior of dry powders primarily by reducing adhesion between particles, thus increasing powder dispersibility and deposition in the lungs [19]. Formulations containing leucine often demonstrate higher FPF values compared to formulations without leucine [50].

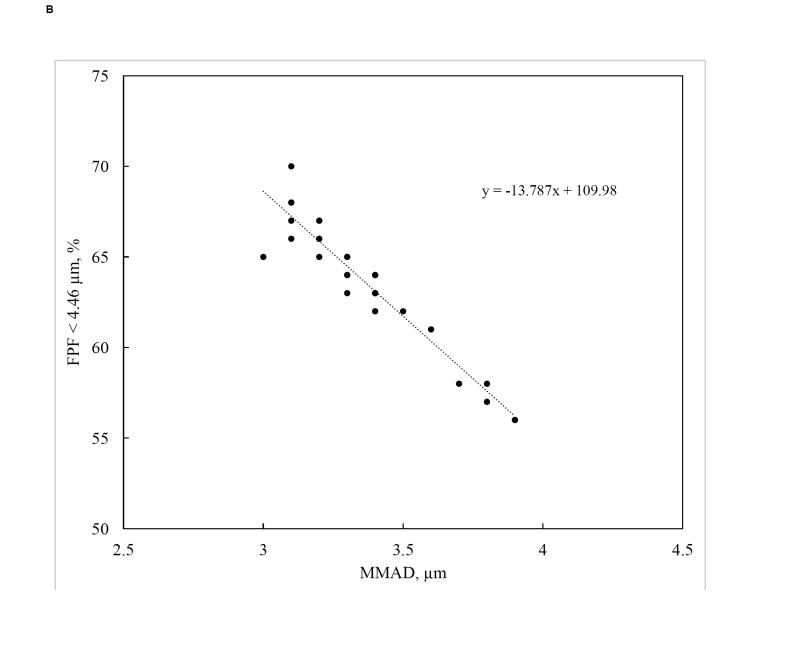

In this study, increasing solution concentration resulted in a significant decrease in FPF<4.46 µm (p=0.038) (Figure 7A). This is consistent with the larger particle MMADs produced at higher feed concentrations. A linear correlation between FPF<4.46 µm and MMAD was observed (Figure 7B). No other factor significantly affected FPF<4.46 µm. While the general trends for FPF< 2.82 µm were similar to those for FPF< 4.46 µm, no factors significantly affected FPF< 2.82 µm. This is not unexpected as 1) this parameter is most impacted by the minor mode of the particle size distribution and 2) no parameters significantly affected the average size of the minor size mode. However, given the importance of this smaller size fraction on lung deposition, a wider parameter space could be evaluated to identify variables that could be tuned to increase its value.

Fig. 7.

A) Main effects plot of FPF < 4.46 µm and B) Linear correlation between FPF < 4.46 µm and MMAD (R2 = 0.905).

3.2.5. Optimization of Input Variables

A theoretical optimization was performed to identify values of the input variables to produce a dry powder with maximum yield, MMAD values between 1 and 5 µm, and maximized FPF. Only optima within the experimental region were examined. The optimal values predicted were to minimize pH at a value of 3, inlet temperature at 155°C, and solution flow rate at 5 mL/min. The other two variables were optimized at mid-range levels of 0.56 wt % for solution concentration and 450 L/hr for atomizer flow rate. These values suggest that further investigation of input variables beyond those tested in the CCD could result in better optimization of powder yield and aerodynamic properties for this set of compounds. In particular, evaluation of pH below 3, inlet temperatures below 155°C, and solution flow rates below 5 mL/min may improve the optimization. While these parameters would remain important for aerosol generation at larger scales, further experimentation would be necessary to determine the similarity of the process upon scale up as only a few publications have reported on the scale up of spray drying from the laboratory to pilot scale or industrial scale [51].

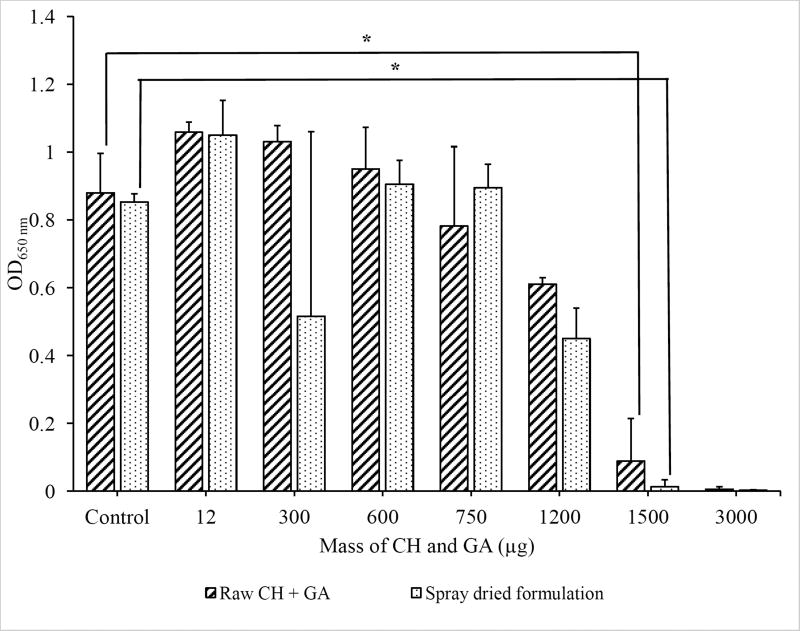

3.2.6. Potency of Spray Dried Formulation

The impact of spray drying on the potency of the combination treatment was determined. Upon treatment of P. aeruginosa biofilms with solutions of the raw materials or the spray dried powders, loss in biofilm viability was observed with exposure at the same antibiotic and dispersion compound dose with both treatments (Figure 8). Since no statistically significant differences were observed in bacterial viability between the raw materials and spray dried powders, spray drying did not alter the potency of the drug compounds.

Fig. 8.

Optical density at 650 nm (n=4; *p < 0.05) of residual P. aeruginosa PAO1 biofilms after treatment with the spray dried formulation or an equivalent dose of raw CH + GA.

3.2.7. Limitations of the Current Study

Current clinical trials with ciprofloxacin DPIs provide 32.5 mg of ciprofloxacin (total powder load of 50 mg) [52]. To achieve this dose of ciprofloxacin and maintain the dose of dispersion compound required for effective treatment with the powders formulated in the current study, multiple capsules and inhalations would be required for each treatment. For greater patient acceptance, the number of capsules could be reduced by using an Aerolizer® device modified to accommodate larger capsules [53] or by using a more potent dispersion compound. Second, additional factors that impact dry powder dispersion and deposition in patients should be taken into account in future studies. In particular, the dependence of device resistance and inspiratory flow rate on the performance of the dry powders developed in this study remains a critical issue to be investigated.

4. Conclusions

Combinations of CH and GA were more effective in eradicating bacterial biofilms, killing biofilms at lower antibiotic concentrations compared to CH alone. The effects of five input variables (solution pH, solids concentration of the spray dried solution, spray dryer inlet temperature, atomizer air flow rate, and solution flow rate) on the yield and aerodynamic properties of spray dried combinations of CH, GA, and leucine were evaluated by central composite design. Powder yield was primarily affected by variables that determine cyclone efficiency, i.e. the atomizer flow rate, solution concentration, and solution flow rate. Key aerodynamic properties of the powders, MMAD and FPF < 4.46 µm, were mainly impacted by the solution concentration. Though because a bimodal distribution in MMAD was observed, evaluating the impact of each particle mode on powder aerodynamic properties led to the identification of an additional input variable, solution flow rate, that significantly impacted MMAD. The results show that dry powder aerosols containing a combination treatment effective against P. aeruginosa biofilms could be developed by spray drying and result in powders with high drug concentrations (90% CH and GA), reasonable yields, and good aerodynamic properties for inhalation without loss of drug potency.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (grant numbers AI096007 and UL1RR024979) and the PhRMA Foundation. This work utilized the Hitachi S-4800 SEM in the University of Iowa Central Microscopy Research Facilities that was purchased with funding from the NIH SIG grant 1 S10 RR022498-01. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

Abbreviations

- CH

ciprofloxacin hydrochloride

- EF

emitted fraction

- FPF

fine particle fraction

- GA

L-glutamic acid

- GSD

geometric standard deviation

- IOG

incidence of growth

- MBEC

minimum biofilm eradication concentration

- MHB

Mueller Hinton Broth

- MMAD

mass median aerodynamic diameter

- NGI

next generation impactor

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Taylor PK, Yeung ATY, Hancock REW. Antibiotic resistance in Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms: Towards the development of novel anti-biofilm therapies. J. Biotechnol. 2014;191:121–130. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2014.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aaron SD, Ferris W, Ramotar K, Vandemheen K, Chan F, Saginur R. Single and combination antibiotic susceptibilities of planktonic, adherent, and biofilm-grown Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolates cultured from sputa of adults with cystic fibrosis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2002;40:4172–4179. doi: 10.1128/JCM.40.11.4172-4179.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mall MA, Hartl D. CFTR: cystic fibrosis and beyond. Eur. Respir. J. 2014;44(4):1042–1054. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00228013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lam J, Vaughan S, Parkins MD. Tobramycin inhalation powder (TIP): an efficient treatment strategy for the management of chronic Pseudomonas Aeruginosa infection in cystic fibrosis. Clin. Med. Insights: Circ., Respir. Pulm. Med. 2013;7:61–77. 17. doi: 10.4137/CCRPM.S10592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kostakioti M, Hadjifrangiskou M, Hultgren SJ. Bacterial biofilms: development, dispersal, and therapeutic strategies in the dawn of the postantibiotic era. Cold Spring Harbor Perspect. Med. 2013;3(4):a010306/1–a010306/23. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a010306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Alkawash MA, Soothill JS, Schiller NL. Alginate lyase enhances antibiotic killing of mucoid Pseudomonas aeruginosa in biofilms. Acta Pathologica, Microbiologica, et Imuunologica Scandinavica. 2006;114(2):131–138. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0463.2006.apm_356.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sauer K, Cullen MC, Rickard AH, Zeef LAH, Davies DG, Gilbert P. Characterization of nutrient-induced dispersion in Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1 biofilm. J. Bacteriol. 2004;186(21):7312–7326. doi: 10.1128/JB.186.21.7312-7326.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Banin E, Brady KM, Greenberg EP. Chelator-induced dispersal and killing of Pseudomonas aeruginosa cells in a biofilm. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2006;72(3):2064–2069. doi: 10.1128/AEM.72.3.2064-2069.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen X, Stewart P. Biofilm removal caused by chemical treatments. Wat. Res. 2000;34(17):4229–4233. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Boles BR, Thoendel M, Singh PK. Rhamnolipids mediate detachment of Pseudomonas aeruginosa from biofilms. Mol. Microbiol. 2005;57(5):1210–1223. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2005.04743.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Moulton RC, Montie TC. Chemotaxis by Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J. Bacteriol. 1979;37(1):274–280. doi: 10.1128/jb.137.1.274-280.1979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sommerfeld Ross S, Fiegel J. Nutrient dispersion enhances conventional antibiotic activity against Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents. 2012;40:177–181. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2012.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yang MY, Chan JGY, Chan H-K. Pulmonary drug delivery by powder aerosols. Journal of Controlled Release. 2014;193:228–240. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2014.04.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hoppentocht M, Hagedoorn P, Frijlink HW, de Boer AH. Technological and practical challenges of dry powder inhalers and formulations. Adv. Drug Del. Rev. 2014;75:18–31. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2014.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.VanDevanter DR, Geller DE. Tobramycin administered by the TOBI(®) Podhaler(®) for persons with cystic fibrosis: a review. Medical Devices (Auckland, NZ) 2011;4:179–188. doi: 10.2147/MDER.S16360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Uttley L, Tappenden P. Dry powder inhalers in cystic fibrosis: same old drugs but different benefits? Curr. Opin. Pulm. Med. 2014;20(6):607–612. doi: 10.1097/MCP.0000000000000109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Klockgether J, Munder A, Neugebauer J, Davenport CF, Stanke F, Larbig KD, Heeb S, Schöck U, Pohl TM, Wiehlmann L, Tümmler B. Genome diversity of Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1 laboratory strains. J. Bacteriol. 2010;192(4) doi: 10.1128/JB.01515-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ceri H, Olson ME, Stremick C, Read RR, Morck D, Buret A. The calgary biofilm device: new technology for rapid determination of antibiotic susceptibilities of bacterial biofilms. J. Clin. Microbiol. 1999;37:1771–1776. doi: 10.1128/jcm.37.6.1771-1776.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Prota L, Santoro A, Bifulco M, Aquino RP, Mencherini T, Russo P. Leucine enhances aerosol performance of naringin dry powder and its activity on cystic fibrosis airway epithelial cells. Int. J. Pharm. 2011;412(1–2):8–19. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2011.03.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fiegel J, Garcia-Contreras L, Thomas M, verBerkmoes J, Hickey A, Edwards D. Preparation and in vivo evaluation of a dry powder for inhalation of capreomycin. Pharm. Res. 2008;25(4):805–811. doi: 10.1007/s11095-007-9381-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Thomas EK. Development of a dry powder aerosol for the dispersion and eradication of respiratory biofilms. Masters Dissertation. 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vanbever R, Mintzes JD, Wang J, Nice J, Chen D, Batycky R, Langer R, Edwards DA. Formulation and physical characterization of large porous particles for inhalation. Pharm Res. 1999;16(11):1735–42. doi: 10.1023/a:1018910200420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yu L, Ng K. Glycine crystallization during spray drying: the pH effect on salt and polymorphic forms. J Pharm Sci. 2002;91(11):2367–75. doi: 10.1002/jps.10225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Billon A, Bataille B, Cassanas G, Jacob M. Development of spray-dried acetaminophen microparticles using experimental designs. Int. J. Pharm. 2000;203(1–2):159–168. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5173(00)00448-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Buchi Spray Drying Training Papers. 2002 [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stanier C. Personal Communication. 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bronsky EA, Grossman J, Henis MJ, Gallo PP, Yegen U, Della CG, Kottakis J, Mehra S. Inspiratory flow rates and volumes with the Aerolizer dry powder inhaler in asthmatic children and adults. Curr Med Res Opin. 2004;20(2):131–7. doi: 10.1185/030079903125002793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Elkins MR, Robinson P, Anderson SD, Perry CP, Daviskas E, Charlton B. Inspiratory Flows and Volumes in Subjects with Cystic Fibrosis Using a New Dry Powder Inhaler Device. The Open Respiratory Medicine Journal. 2014;8:1–7. doi: 10.2174/1874306401408010001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tiddens HA, Geller DE, Challoner P, Speirs RJ, Kesser KC, Overbeek SE, Humble D, Shrewsbury SB, Standaert TA. Effect of Dry Powder Inhaler Resistance on the Inspiratory Flow Rates and Volumes of Cystic Fibrosis Patients of Six Years and Older. J. Aerosol Med. 2006;19(4):456–465. doi: 10.1089/jam.2006.19.456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Seville PC, Learoyd TP, Li HY, Williamson IJ, Birchall JC. Amino acid-modified spray-dried powders with enhanced aerosolization properties for pulmonary drug delivery. Powder Technol. 2007;178(1):40–50. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stahl K, Claesson M, Lilliehorn P, Linden H, Backstrom K. The effect of process variables on the degradation and physical properties of spray dried insulin intended for inhalation. Int. J. Pharm. 2002;233(1–2):227–237. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5173(01)00945-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tewa-Tagne P, Degobert G, Briancon S, Bordes C, Gauvrit J-Y, Lanteri P, Fessi H. Spray-drying nanocapsules in presence of colloidal silica as drying auxiliary agent: formulation and process variables optimization using experimental designs. Pharm Res. 2007;24(4):650–61. doi: 10.1007/s11095-006-9182-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Maltesen MJ, Bjerregaard S, Hovgaard L, Havelund S, van de Weert M. Quality by design - Spray drying of insulin intended for inhalation. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2008;70(828–838) doi: 10.1016/j.ejpb.2008.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Masters K. Spray drying handbook. Spray drying handbook. (3) 1979 [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wan LSC, Heng PWS, Chia CGH. Preparation of coated particles using a spray drying process with an aqueous system. Int. J. Pharm. 1991;77(2–3):183–91. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hinds WC. Aerosol technology: Properties, behavior, and measurement of airborne particles. 2. Wiley & Sons; 1999. p. 504. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Patton JS, Byron PR. Inhaling medicines: delivering drugs to the body through the lungs. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2007;6:67–74. doi: 10.1038/nrd2153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Demoly P, Hagedoorn P, de Boer AH, Frijlink HW. The clinical relevance of dry powder inhaler performance for drug delivery. Resp. Med. 2014;108(8):1195–1203. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2014.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Labiris NR, Dolovich MB. Pulmonary drug delivery. Part I: Physiological factors affecting therapeutic effectiveness of aerosolized medications. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2003;56:588–599. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2125.2003.01892.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bjarnsholt T, Jensen PØ, Fiandaca MJ, Pedersen J, Hansen CR, Andersen CB, Pressler T, Givskob M, Høiby N. Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms in the respiratory tract of cystic fibrosis patients. Pediatr. Pulmonol. 2009;44(6):547–548. doi: 10.1002/ppul.21011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sou T, Kaminskas LM, Nguyen T-H, Carlberg R, McIntosh MP, Morton DAV. The effect of amino acid excipients on morphology and solid-state properties of multi-component spray-dried formulations for pulmonary delivery of biomacromolecules. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2013;83(2):234–243. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpb.2012.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Najafabadi AR, Gilani K, Barghi M, Rafiee-Tehrani M. The effect of vehicle on physical properties and aerosolisation behaviour of disodium cromoglycate microparticles spray dried alone or with Lleucine. Int J Pharm. 2004;285(1–2):97–108. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2004.07.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Raula J, Lahde A, Kauppinen EI. Aerosolization behavior of carrier-free L-leucine coated salbutamol sulphate powders. Int J Pharm. 2009;365(1–2):18–25. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2008.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Witschi HP, Brian JD. Handbook of Experimental Pharmacology. 1. Springer-Verlag Berlin Heldelberg; 1985. Toxicology of Inhaled Medicines. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Heyder J. Deposition of inhaled particles in the human respiratory tract and consequences for regional targeting in respiratory drug delivery. Proc. Am. Thorac. Soc. 2004;1(4):315–320. doi: 10.1513/pats.200409-046TA. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Morrow PE. An evaluation of the physical properties of monodisperse and heterodisperse aerosols used in the assessment of bronchial function. Chest. 1981;80(6 Suppl):809–13. doi: 10.1378/chest.80.6.809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Park C-W, Li X, Vogt FG, Hayes D, Jr, Zwischenberger JB, Park E-S, Mansour HM. Advanced spray-dried design, physicochemical characterization, and aerosol dispersion performance of vancomycin and clarithromycin multifunctional controlled release particles for targeted respiratory delivery as dry powder inhalation aerosols. Int J Pharm. 2013;455(1–2):374–392. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2013.06.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Abdelrahim ME. Emitted dose and lung deposition of inhaled terbutaline from Turbuhaler at different conditions. Respiratory Medicine. 2010;104(5):682–689. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2009.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Newman SP, Chan HK. In vitro/in vivo comparisons in pulmonary drug delivery. J. Aerosol. Med. Pulm. Drug Deliv. 2007;21(1):77–84. doi: 10.1089/jamp.2007.0643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Simon A, Amaro MI, Cabral LM, Healy AM, de Sousa VP. Development of a novel dry powder inhalation formulation for the delivery of rivastigmine hydrogen tartrate. Int J Pharm. 2016;501(1–2):124–138. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2016.01.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Thybo P, Hovgaard L, Lindeløv JS, Brask A, Andersen SK. Scaling Up the Spray Drying Process from Pilot to Production Scale Using an Atomized Droplet Size Criterion. Pharmaceutical Research. 2008;25(7):1610–1620. doi: 10.1007/s11095-008-9565-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Dorkin HL, Staab D, Operschall E, Alder J, Criollo M. Ciprofloxacin DPI: a randomised, placebo-controlled, phase IIb efficacy and safety study on cystic fibrosis. BMJ Open Respiratory Research. 2015;2(1) doi: 10.1136/bmjresp-2015-000100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Parumasivam T, Leung SSY, Tang P, Mauro C, Britton W, Chan H-K. The delivery of highdose dry powder antibiotics by a low-cost generic inhaler. The AAPS Journal. 2017;19(1):191–202. doi: 10.1208/s12248-016-9988-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.