Abstract

Autoimmune hepatitis is a rare chronic inflammatory liver disease, affecting all ages, characterised by elevated transaminase and immunoglobulin G levels, positive autoantibodies, interface hepatitis at liver histology and good response to immunosuppressive treatment. If untreated, it has a poor prognosis. The aim of this review is to summarize the evidence for standard treatment and to provide a systematic review on alternative treatments for adults and children. Standard treatment is based on steroids and azathioprine, and leads to disease remission in 80%-90% of patients. Alternative first line treatment has been attempted with budesonide or cyclosporine, but their superiority compared to standard treatment remains to be demonstrated. Second-line treatments are needed for patients not responding or intolerant to standard treatment. No randomized controlled trials have been performed for second-line options. Mycophenolate mofetil is the most widely used second-line drug, and has good efficacy particularly for patients intolerant to azathioprine, but has the major disadvantage of being teratogenic. Only few and heterogeneous data on cyclosporine, tacrolimus, everolimus and sirolimus are available. More recently, experience with the anti-tumour necrosis factor-alpha infliximab and the anti-CD20 rituximab has been published, with ambivalent results; these agents may have severe side-effects and their use should be restricted to specialized centres. Clinical trials with new therapeutic options are ongoing.

Keywords: Autoimmune hepatitis, Standard treatment, Second-line treatment, Adults, Children

Core tip: The first part of this review summarizes the standard therapeutic approach for autoimmune hepatitis (steroids and azathioprine) and the evidence on which it is based. The second part reviews systematically published data on first and second line alternative treatments. This information is summarized in two comprehensive tables, one for adult and one for paediatric patients.

INTRODUCTION

Autoimmune hepatitis (AIH) is a rare inflammatory liver disease of unknown origin characterised by high transaminase and immunoglobulin G (IgG) levels, positive autoantibodies, and, histologically, by interface hepatitis[1-4]. The condition affects all ages, and has a female preponderance[5]. There is no single diagnostic test[1,2]. The International Autoimmune Hepatitis Group (IAIHG) established comprehensive diagnostic criteria in 1993[6], based on expert opinion, intended to be used for research purposes. After their evaluation in a number of studies, the criteria were updated in 1999[7]. A simplified, clinical practice-friendly version was published in 2008[8]. These criteria are intended to help in guiding diagnosis and decision on therapy initiation in patients presenting with a clinical picture suggesting AIH, and have received extensive external validation since publication[9-11].

AIH is divided in type 1 and type 2, the latter being rare in adults and representing 30% of juvenile AIH. The distinction is made serologically: type 1 AIH is positive for anti-nuclear antibodies (ANA), and/or anti-smooth muscle antibodies (SMA), while type 2 AIH is positive for anti-liver kidney microsomal antibodies type 1 (anti-LKM1) and/or anti-liver cytosol type 1 (anti-LC1)[12].

AIH is the first liver disease for which pharmacologic treatment has been shown to improve survival. Indeed, it has an excellent response to steroid-based immunosuppressive therapy, with a reported response rate of 75%-90%[2]. Steroid-response is a crucial feature of AIH, and it is part of the IAIHG revised diagnostic criteria[7]. Lack of response to steroids should prompt a review of the diagnosis.

Treatment indications

If untreated, AIH has a severe prognosis. This knowledge derives from early clinical trials, when “HBsAg-negative hepatitis” (as AIH was called then) patients were treated with corticosteroids vs placebo. One placebo controlled study reported a 5-year survival rate of 32% in untreated patients vs 82% in patients treated with steroids[13]. According to the guidelines on the management of AIH by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD)[2], the 6-mo survival rate in untreated patients is about 60%. Therefore, once diagnosed, AIH should be treated promptly. Elderly patients with mild pauci- or a-symptomatic disease, who have a high risk of developing steroid side effects, may be an exception, and in this clinical context treatment vs watchful waiting should be carefully evaluated case by case[14-16]. Untreated patients need a close follow-up. Treatment must be always initiated in the presence of clinical symptoms, severe biochemical and/or histological disease activity. Younger subjects, particularly children and adolescents, who have a more aggressive disease, should be treated without delay[17].

Treatment aims

The aim of treatment is disease remission, which is reached if the following criteria are met: (1) absence of clinical symptoms; (2) normal transaminase levels; and (3) normal IgG levels. In children/adolescents, negative or very low-titre autoantibodies (< 1:20 for ANA/SMA; < 1:10 for anti-LKM1) are an additional criterion of remission[3], which remains to be evaluated in adults by longitudinal studies.

In the past, transaminase levels below twice the upper limit of normal (ULN) have been considered proof of remission, but it is now clear that patients with abnormal transaminase levels have progressive disease[2,18]. Once remission is achieved, the lowest possible dose of immunosuppressive drugs should be used to maintain long-term remission with no or minimal side effects.

Disease relapse is defined as transaminase levels rising above the ULN after remission[12]. Relapse occurs mostly if the dose of the immunosuppressive drugs is reduced, or in case of non-adherence. Non-adherence is a frequent clinical problem, particularly in adolescents[19] and young adults, and is often due to real or perceived treatment side effects. It should always be suspected in case of relapse while on a stable dose of immunosuppressive drugs.

AIM AND METHODOLOGY OF THE SYSTEMATIC REVIEW

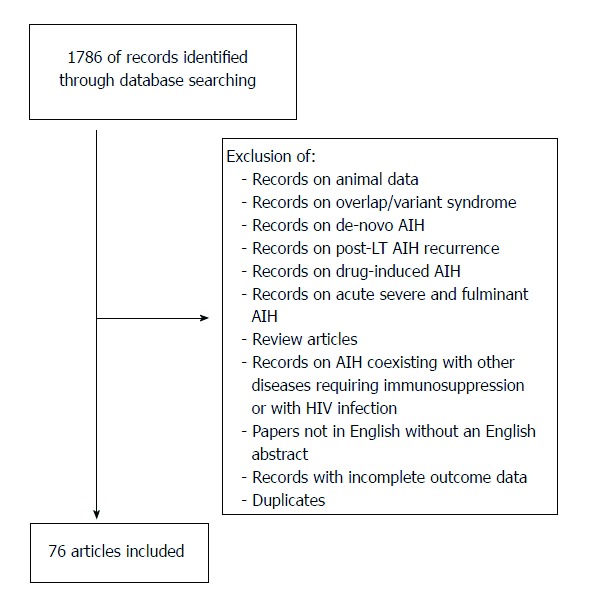

The aim of this review is, in its first part, to critically summarize the evidence on which standard AIH treatment (prednisone and azathioprine) is based, and, in its second part, to provide a systematic review of the published data on alternative treatments. For the purpose of the systematic review of the literature on alternative AIH treatment, publications cited in PubMed (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed) were selected using the search words “autoimmune hepatitis” and “treatment”. Citations were chosen on the basis of their relevance to the aim of this article (Figure 1). Fundamental characteristics of the abstracts judged pertinent to the review were noted, and full-length original articles were selected from the abstracts. Seventy-six articles were identified, 22 of them are not discussed in this review because of anedoctal reporting, the remaining 54 are included in Table 1 (adults) and Table 2 (children). Children/adolescents have a more aggressive disease, with a more frequent acute presentation[20] and therefore need a different management[17]. For this reason, the present review article discusses adult and pediatric treatment separately.

Figure 1.

Selection of relevant articles for the systematic literature review on alternative AIH treatments. AIH: Autoimmune hepatitis; LT: Liver transplantation.

Table 1.

Proposed schedule of prednisone tapering during remission-induction therapy in adults[25]

| Prednisone mg/d | Azathioprine | |

| Week 1 | 60.0 | Check transaminase levels every week before reducing the prednisone dose: if transaminase levels stop decreasing, add azathioprine 1-2 mg/kg per day, if jaundice is subsiding |

| Week 2 | 50.0 | |

| Week 3 | 40.0 | |

| Week 4 | 30.0 | |

| Week 5 | 25.0 | |

| Week 6 | 20.0 | |

| Week 7 | 15.0 | |

| Week 8-9 | 12.5 | |

| Week 10-11 | 10.0 | |

| If severe steroid side effects: consider reducing to 2.5 mg/d for 2 wk and then stopping prednisone |

Table 2.

| Prednisone mg/kg/d | Azathioprine | |

| Week 1 | 2.0 | Check transaminase levels every week before reducing the prednisone dose: if transaminase levels stop decreasing, add azathioprine starting with 0.5 mg/kg per day, if jaundice is subsiding, at increasing doses up to 2-2.5 mg/kg/d until biochemical control |

| Week 2 | 1.75 | |

| Week 3 | 1.50 | |

| Week 4 | 1.25 | |

| Week 5 | 1.00 | |

| Week 6 | 0.75 | |

| Week 7 | 0.50 | |

| Week 8-9 | 0.25 | |

| Week 10-11 | 0.10-0.20 | |

| If severe steroid side effects: consider reducing to 2.5 mg/d for 2 wk and then stopping prednisone |

STANDARD TREATMENT

Why do we treat autoimmune hepatitis with steroids and azathioprine?

Standard treatment is based on steroids and azathioprine (Table 1). A systematic review of randomized controlled trials focused on these two drugs up to 2009 was published in 2010[21]. The exact azathioprine mechanism of action is unclear, but it is most probably linked to suppression of nucleic acid synthesis. The first evidence for steroid benefit in inducing remission and improving survival in treatment-naïve AIH stems from three trials performed in the 1970s, which demonstrated a significant better survival in patients with so called “HBsAg-negative chronic active liver disease” treated with steroids[22-24] in comparison to untreated patients. It should be noted that at that time the hepatitis C virus (HCV) had not been discovered and it is likely that some patients with HCV were included in the trials, although “HBsAg-negative chronic active hepatitis” was characterised by high globulin levels, female preponderance, and presence of autoantibodies, all features of AIH[13]. The benefit of steroid treatment would have probably been even greater if HCV-patients had been excluded[25]. In the Royal Free Hospital trial[22], 49 well characterised patients, including children, were randomised in a steroid-treated group (prednisolone 15 mg/d) and a placebo group. Mortality rate was 14% in the treated group, and 56% in the placebo group, with a follow-up ranging from 30 to 72 mo. The trial from the Mayo Clinic published one year later[23] included 63 patients, divided into four groups. Two groups were treated with protocols similar to current guidelines: the first group was treated with prednisone alone starting with 60 mg/d, tapered to a maintenance dose of 20 mg/d over 4 wk, the second group received prednisone 30 mg/d tapered to a maintenance dose of 10 mg/d combined with azathioprine at a fixed dose of 50 mg/d. The remaining groups were treated with azathioprine alone 100mg/d and placebo, respectively. The mortality rate in the first and second group was very low (6% and 7%), compared to a mortality rate of 36% and 41% in the groups treated with azathioprine alone or placebo. The follow-up period ranged from 3 mo to 3.5 years. The side effect rate was lower in the azathioprine-prednisone group than in the prednisone alone group (10% vs 44%). A trial from King’s College Hospital published in 1973[24] included 47 patients, divided into two groups, one treated with prednisone 15 mg/d, and the other with azathioprine alone, 75 mg/d, with a follow-up of two years. The mortality rate in the prednisone group was 5%, as compared to a mortality rate of 24% in the azathioprine group. From these early trials it is clear that prednisone is very effective in treating AIH, and that azathioprine alone is not able to obtain disease remission. Following these reports, strategies were sought to optimize the treatment schedule, i.e. to find the minimal doses of prednisone or prednisone/azathioprine able to control the disease with minimal side effects. A trial published in 1975[26] included 120 patients and compared four different schedules: (1) prednisone starting at 60 mg/d tapered to a maintenance dose of 20 mg/d; (2) prednisone starting at 30 mg/d tapered to 10 mg/d together with a 50 mg/d fixed dose of azathioprine; (3) prednisone at 60 mg/d tapered to a maintenance dose of 10 mg/d given on alternate days; and (4) placebo or azathioprine on a fixed dose of 100 mg/d without steroids, as control. Biochemical remission was achieved in 80% of patients in the first two groups, in 74% in the third group and in 34% in the control group. Histological remission was achieved in 57% and 60% of patients in the first two groups, but in only 19% and 24% in the third and in the control group. Side effects were less frequent in patients treated with prednisone/azathioprine from disease presentation, for which a lower dose of prednisone was used, leading to the conclusion that combined treatment is preferable. Of note, this trial enrolled “post-pubertal subjects”, including patients from the age of 12 years. An additional trial published in 1982[27] compared a fixed low-dose prednisone alone (10 mg/d for body weight < 70 kg, 15 mg/d for body weight ≥ 70 kg) in 37 patients with a fixed low-dose azathioprine alone (5 mg/kg per week for the first 2 wk, subsequently 10 mg/kg per week) in 47 patients. Mortality was very high in both groups at 1 year (27% and 28% respectively), indicating that a low prednisone dose and azathioprine alone are inadequate.

Despite the limitations of these early trials, prednisone ± azathioprine remains the mainstay of treatment for AIH, several reports showing high remission rates and favourable outcomes in both adult and juvenile AIH[20,28-38].

Of note, azathioprine monotherapy, though unsuccessful in the induction of remission, is effective in adults as maintenance therapy, at a dose of 2 mg/kg per day[39]. A 5-patient report suggests that it may be effective also in children[40]. In a recent retrospective series, 87% of 66 children with AIH were reported to maintain sustained biochemical remission (normal transaminase levels) in association with low 6-thioguanine nucleotides (TGN) levels (50-250 pmol 8 x 10 red blood cell cont) on an azathioprine dose of 1.2-1.6 mg/kg per day with or without associated steroids[41].

How to use prednisone and azathioprine

There is no treatment schedule applicable to all AIH patients. The suggested algorithms and treatment schedules must be tailored to the single patient, taking into account the severity of the disease, age and co-morbidities[1].

The AASLD guidelines published in 2010[2] recommend two alternative schedules: either prednisone alone at a dose of 60 mg/d or a combination of prednisone 30 mg/d and azathioprine 50 mg/d as initial treatment, favouring the latter because of fewer steroid side-effects[26]. However, as azathioprine can be hepatotoxic, particularly in cirrhotic and jaundiced patients[25], the more recent guidelines by the European Association for the Study of the Liver (EASL) recommend that it is added after two weeks of steroid monotherapy [predniso(lo)ne 1 mg/kg per day in adults], when partial disease control has been achieved[1]. In addition, this approach avoids the problem of distinguishing between azathioprine-induced hepatotoxicity and non-response, this distinction being an important issue in clinical practice. A retrospective series of 133 adult patients reports better results with a combination of steroids and another immunosuppressant (azathioprine in 96%, other unspecified drugs in 4%) from disease presentation compared to steroids alone or steroids followed by the addition of azathioprine/other immunosuppressants. Of note, only 2% of the patients included in this study were jaundiced at presentation[42], possibly explaining the high remission rate on azathioprine, without hepatotoxicity.

Prednisone should be rapidly tapered (Table 1) to minimise steroid side effects. This rapid decrease of the prednisone dose requires weekly checks of the transaminase levels to monitor response. Azathioprine should be added if the transaminase levels stop decreasing on steroid treatment alone (Table 1). Ultimately 85% of the patients will need azathioprine in addition to low-dose prednisone[12]. This protocol was originally used for children[25], but it is suitable to treat adult patients as well, because it allows to avoid azathioprine in a small proportion of patients and especially because it limits steroid side effects, which are often the reason for non-adherence. The initial recommended dose of azathioprine in adults is 50 mg/d or 1 mg/kg per day[2]. If steroid side effects are severe and require steroid discontinuation, the azathioprine dose is increased to 2 mg/kg per day.[39,43]

In children, the recommended treatment schedule is similar to that of adults, but a higher steroid dose is required due to the more aggressive disease course in this age group (Table 2). Children were included in early clinical trials[22,26], but a sub-analysis of paediatric patients was not performed, and the numbers were small. Current recommendations are based on series from large centres, which report a remission rate of about 90% using predniso(lo)ne ± azathioprine[20,35,36]. Conventional treatment of juvenile AIH consists of prednisolone (or prednisone) 2 mg/kg per day (maximum 60 mg/d), decreased over a period of 4 to 8 wk in parallel to the decline of transaminase levels, to a maintenance dose of 2.5-5 mg/d (Table 2). Long-term low daily doses are not associated with impaired adult height[44]. The timing for the addition of azathioprine as a steroid-sparing agent varies according to the protocols used in different centres. In some, azathioprine is added only in the presence of steroid adverse effects, or if the transaminase levels stop decreasing on steroid treatment alone. In other centres azathioprine is added after a few weeks of steroid treatment in all patients, when the serum aminotransferase levels begin to decrease. Some centres use a combination of steroids and azathioprine from the beginning, but caution is recommended because of the azathioprine hepatotoxicity mentioned above[1,2,34]. The initial recommended azathioprine dose is 0.5 mg/kg per day[12], which can be increased to 1-2 mg/kg per day until normalization of the transaminase levels is reached. As in adults, azathioprine alone has been shown to be able to control the disease as long-term maintenance therapy, although only in retrospective series[40,41,45].

As AIH is very sensitive to prednisone, a maintenance dose of 5 mg/d is effective in controlling the disease, usually with, but sometimes without, azathioprine. Steroid reduction below 5 mg/d (or 2.5 mg/d in children) requires careful monitoring of transaminase levels, even if implemented after long-term disease remission. The dose should be reduced very slowly, e.g., by 1 mg per month if 1 mg prednisone tablets are available, or, if not available, by reducing to 5-2.5 mg on alternate days for 1-2 mo, and then to 2.5 mg/d.

Side effects of steroids and azathioprine

Steroid side effects are dose and time dependent, and arise if a dose exceeding 7.5-10 mg/d is administered over several months[25]. The most common side effect is the development of cushingoid features. In a retrospective monocentric study of 103 adult AIH patients[46], mostly treated according to a standard protocol with a steroid starting dose of 1 mg/kg per day and a mean follow-up period of 95 mo, 15.5% developed cushingoid features. Although not severe, these changes are often a great concern for the patients, and may lead to non-adherence, with the dangerous consequence of poor disease control. Almost half of AIH patients discontinue steroids because of cosmetic changes (including acne) or obesity[47]. Severe, but less frequent steroid side effects include osteoporosis, brittle diabetes, cataract, psychosis and hypertension[2]. They are mainly related to the initial high dose, and are reversible[43,46]. Monitoring of these complications is advisable, including ophthalmologic controls and bone density scans on a regular basis.

Azathioprine side effects affect 10%-20% of patients and include hepatotoxicity, acute cholestatic hepatitis, pancreatitis, nausea and vomiting, rash, bone marrow suppression, veno-occlusive disease, opportunistic infections, and malignancy[2]. The most common side effect is bone marrow suppression, which is unpredictable, and can be aggravated by concomitant cytopaenia due to liver disease and hypersplenism. Haematological monitoring is necessary, particularly at the beginning of treatment. Measurement of erythrocyte concentrations of thiopurine methyltransferase (TPMT) activity may be advisable before institution of azathioprine therapy, but does not invariably predict response to the drug or toxicity[48,49]. TPMT genotyping predicts azathioprine haematological toxicity in those rare individuals with variant homozygosity, while heteroxygotes do not experience more toxicity than wild-type patients[50]. Five percent of patients develop early intolerance, most frequently with nausea and vomiting.

A possible complication of long-term treatment with azathioprine is the development of malignancies. In one study aiming at investigating disease control by azathioprine monotherapy at a dose of 2 mg/kg per day, 5 of 72 patients (7%) developed malignancies over a median follow up of 12 years[39]. Recently, two cases of T-cell lymphoma in adolescents treated with azathioprine for AIH were reported[51]. Thus, a lower azathioprine dose in association with low-dose steroids may be preferable for long-term maintenance therapy. Azathioprine is considered to be safe in pregnancy[52-54].

Measurement of the azathioprine metabolites 6-TGN and 6-methylmercaptopurine can be helpful in identifying drug toxicity and non-adherence, and in distinguishing azathioprine hepatotoxicity from disease non-response, as shown by a retrospective study in adults[55], and a small prospective study in children[56], but an ideal therapeutic level of the 6-thioguanine metabolites has not been established for AIH, unlike for inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD).

Treatment withdrawal

The AASLD[2] and the EASL guidelines[1] recommend a treatment duration of at least 2 and 3 years respectively, and both advise against a trial of treatment withdrawal before 2 years of complete biochemical remission. They recommend performing a liver biopsy before attempting treatment discontinuation, because histological inflammatory activity can still be present despite biochemical remission, predicting relapse. A recent report on 28 patients in whom treatment was withdrawn without histological evaluation, shows that the 54% of patients who did not relapse had transaminase levels less than half the ULN and IgG levels below 12 g/L on low-dose monotherapy (azathioprine/mercaptopurine or steroids) for at least 2 years, suggesting that patients meeting these parameters may avoid pre-withdrawal liver biopsy[57].This suggestion, however, requires confirmation by other centres.

Relapse after treatment withdrawal is frequent, having been reported in some 80% of patients[1,2,58]. Repeated relapses are associated with a poorer prognosis and a higher rate of drug side effects[2]. For this reason, patients experiencing a first relapse episode after appropriate evaluation of disease remission, should undergo life-long low-dose immunosuppressive therapy[1].

For AIH type 2, relapse is almost universal if treatment is completely withdrawn[20], and long-term low-dose maintenance therapy should be planned from the diagnosis. Since this condition mostly affects children, adolescents and young adults, life-long duration of the therapy should be discussed and carefully explained to the patients and their family.

ALTERNATIVE TREATMENTS

For patients who experience azathioprine side effects, ranging from the relatively frequent early gastrointestinal intolerance to the rarer and more serious bone marrow suppression, and for poor responders to standard treatment, alternative regimens are needed, primarily to avoid high-dose steroid side-effects. A systematic review of the published clinical data on pharmacological treatments different from prednisone and azathioprine is provided in this section. Treatments for whom there are only anecdotal data are not discussed cyclophosphamide[59], methotrexate[60-62], ursodeoxycholic acid[63-69], etanercept[70], plasma exchange[71], intravenous immunoglobulin[72], leukapheresis[73], chloroquine[74], thymostimulin[75], deflazacort[76,77], saireito[78], sympathomimetic amines[79], glycyrrhizin[80], fenofibrate[81].

Budesonide

Budesonide is a glucocorticosteroid with a potent topical effect and a high first-pass uptake (> 90%) in the healthy liver, thus appearing ideal for treating AIH. The first reports on its use included small numbers of patients at different stages of disease and gave controversial results[79-83] (Table 3). Subsequently, a large randomized controlled trial in 203 AIH patients (including 46 children/adolescents) was carried out, involving several European centres[82] (Table 3). Cirrhotic patients were excluded, because the first pass hepatic extraction of budesonide may be reduced in cirrhosis due to portosystemic shunting. In fact, severe complications have been reported in cirrhotic patients on budesonide[83,84], including portal vein thrombosis and Budd-Chiari syndrome, indicating that AIH patients with cirrhosis at diagnosis (at least one third) should not be treated with budesonide. The trial primary end-point was biochemical remission (defined as normalization of transaminase levels) in absence of steroid side effects. The overall results of the trial showed better response to budesonide/azathioprine than to prednisone/azathioprine treatment, the primary end-point being achieved in 60% of patients given budesonide vs 38.8% of those given prednisone[82]. These response rates, however, are below the remission rates achieved with standard treatment, and this has raised concerns. In the control arm, the prednisone dose was reduced as per-protocol, irrespective of the course of the clinical and biochemical response, an approach not recommended in AIH treatment[1], which should be tailored to individual patient response. The initial prednisone dose (40 mg/d) was low at least for children/adolescents[1,12], who should be treated with 2 mg/kg per day (up to 60 mg/d). All patients were prescribed azathioprine from the beginning, irrespective of the presence of jaundice, raising the possibility that the low response rate might be partly due to azathioprine hepatotoxicity[85]. The trial included treatment naïve patients and patients experiencing disease relapse, who are likely to represent a subgroup of poor responders[85]. Moreover, only transaminase levels were used to define biochemical remission, while the combination of normal transaminase and IgG/gammaglobulin levels best predicts absence of histological activity[46,86,87].

Table 3.

Published data on autoimmune hepatitis treatment different from steroids and azathioprine in adults (from age 16)

| Reference, yr | Country | Number and type of patients | Design | Outcome | Follow-up | Dose | Safety |

| Budesonide | |||||||

| Danielsson et al[79], 1994 | Sweden | 13 naïve | Prospective | Significant decrase of mean transaminase levels | 9 mo | 6-8 mg/d | Plasma cortisol reduction in cirrhotic patients |

| Czaja et al[80], 2000 | United States | 10 AZA-NR | Prospective | 3/10 BR | 2-12 mo | 9 mg/d | All patients had side-effects |

| Wiegand et al[81], 2005 | Germany | 12 naïve | Prospective | 10/12 BR | 3 mo | 9 mg/d | 3 discontinued due to side effects |

| Csepregi et al[82], 2006 | Germany | 10 naïve 8 AZA-NR | Prospective | 7/10 naïve BR 8/8 AZA-NR BR | 24 wk | 9 mg/d | Steroids side-effects in cirrhotic patients |

| Zandieh et al[83], 2008 | Canada | 6 AZA-INT 3 PDN-INT | Retrospective | 4/6 AZA-INT CBR 3/3 PDN-INT CBR | 24 wk-8 yr | 1.5-9 mg/d | Not reported |

| Manns et al[84], 20101 | Europe | 208 naïve or relapsing | Prospective, randomized, | 60% BR in budesonide 39% BR in PDN | 6 mo | 9 mg/d | Steroids side effects: 28% in budesonide arm, 53% in PDN arm |

| Mycophenolate mofetil | |||||||

| Richardson et al[177], 2000 | United Kingdom | 3 AZA-INT 4 AZA-NR | Retrospective | 5/7 BR | 46 mo | 2 g/d | Leukopaenia in 1 |

| Zolfino et al[93], 2002 | United Kingdom | 3 second line | Retrospective | 1/3 BR | Not reported | 2 g/d | Not reported |

| Devlin et al[94], 2004 | Canada | 5 second-line | Retrospective | 5/5 BR | Not reported | Not reported | 1 pyelonephritis |

| Chatur et al[95], 2005 | Canada | 11 second-line | Retrospective | 7/11 BR | 10-54 mo | 0.5-2 g/d | Leukopaenia in 1, diarrhoea in 1 |

| Czaja et al[96],2005 | United States | 8 first- and second line | Retrospective | 0/8 CBR | 12-26 mo | 0.5-3 g/ d | None reported |

| Inductivo-Yu et al[97], 2007 | United States | 15 second-line | Retrospective | Significant decrease of mean transaminase levels and of histological fibrosis and inflammation | 41 mo | 2 g/d | None significant |

| Hlivko et al[98], 2008 | United States | 17 naïve 12 second-line | Retrospective | 16/19 BR | Not reported | 0.5-2 g/d | 10 discontinued for side-effects |

| Hennes et al[99], 20082 | Germany | 27 AZA-INT 9 AZA-NR | Retrospective | 57% AZA-INT BR 25% AZA-NR BR | 16 mo | 1-2 g/d | 11 GI side effects |

| Wolf et al[178], 2009 | United States | 16 second-line | Retrospective | 5/16 BR | Not reported | 1-2 g/d | 1 discontinued due to paresthesias |

| Sharzehi et al[100], 2010 | United States | 9 AZA-INT 12 AZA-NR | Retrospective | 21/21 BR | 12 mo | 0.5-2 g/d | 1 discontinued for GI side-effects |

| Baven-Pronk et al[101], 2011 | The Netherlands | 23 AZA-INT 22 AZA-NR | Retrospective | 67% AZA-INT BR 13% AZA-NR BR | 3-133 mo | 0.5-3 g/d | 6 discontinued for side-effects |

| Jothinami et al[102], 2014 | India- United Kingdom | 18 AZA-INT 2 AZA-NR | Retrospective | 14 BR | 5-83 mo | 1-2 g/d | 3 discontinued due to side-effects |

| Zachou et al[103], 2016 | Greece | 109 naïve | Prospective | 83/102 BR at 3 mo | 72 mo | 1.5-2 g/d | 2 discontinued for septicaemia; 5 dose reduction for leukopaenia or infections |

| Gazzola et al[179], 2016 | Australia | 51 AZA-INT 45 AZA-NR | Retrospective | 27/49 AZA-INT BR 17/40 AZA-NR BR | Median: 31.9 mo | 1-2 g/d | 1 death, 2 hospitalisations, 8 GI side effects, 5 infections, 3 cytopoenia, 3 neuropsychiatric, 2 skin cancer, 1 lymphoproliferative disorder |

| Park et al[180], 2016 | South Korea | 1 AZA-INT | Retrospective | 1/1 CBR | 1 yr | 1 g/d | None |

| Cyclosporine A | |||||||

| Mistilis et al[121], 1985 | Australia | 1 AZA-INT | Retrospective | 1/1 BR | 1 yr | Not reported | None |

| Paroli et al[116], 1992 | Italy | 3 naïve | Prospective | 3/3 BR | 1 yr | 5 mg/kg/d | Not reported |

| Person et al[118], 1993 | United States | 1 second-line | Retrospective | BR | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported |

| Sherman et al[114], 1994 | United States | 6 AZA-NR (1 paediatric) | Retrospective | 5/6 BR at 10 wk | Not reported | Not reported | 1 increased serum creatinine |

| Senturk et al[119], 1995 | India | 1 second-line | Retrospective | BR | 1 yr | Not reported | None |

| Fernandes et al[113], 1999 | United States | 5 AZA-NR | Retrospective | 4/5 BR at 3 mo | 27 mo | 3-5 mg/kg/d | Minimal |

| Malekzadeh et al[117], 2001 | Iran | 9 naïve 10 second-line | Prospective | 79% BR and HI | 26 mo | 2-5 mg/kg/d | 4 discontinued due to side effects |

| Zolfino et al[93], 2002 | United Kingdom | 1 second-line | Retrospective | NR | Not reported | Serum level 100-200 μg/L | Not reported |

| Malekzadeh et al[181], 2012 | Iran | 22 steroid-intolerant or NR | Retrospective | 9 BR | 60 mo | Not reported | Hirsutism (frequency not reported) |

| Tacrolimus | |||||||

| Van Thiel et al[134], 1995 | United States | 21 naïve | Prospective | Mean 80% ALT drop at 3 months | 3 mo | 6.6-8 mg/d; blood levels 0.6-1.0 ng/mL | Mild mean creatinine elevation after 1 yr |

| Heneghan et al[137], 1999 | United Kingdom | 7 naïve | Prospective | BR in 86% | Not reported | Not reported | |

| Zolfino et al[93], 2002 | United Kingdom | 5 AZA-NR | Retrospective | 2/5 BR | Not reported | 2-4 mg/d | Not reported |

| Aqel et al[130], 2004 | United States | 11 second-line | Retrospective | Normalization of mean ALT value | 16 mo | 0.5-1 mg/d(blood level < 6 ng/mL) | Minimal |

| Chatur et al[95], 2005 | Canada | 3 second-line | Retrospective | 3/3 NR | 10-54 mo | 2-4 mg/d | 1 discontinued for abdominal pain |

| Larsen et al[131], 2007 | Denmark | 9 AZA- or MMF-NR (1 pediatric) | Retrospective | 9/9 BR | 12-37 mo | 2 mg/d (target blood level < 6 ng/mL) | 1 mild tremor |

| Tannous et al[133], 2011 | United States | 13 second-line | Retrospective | 12/13 BR | 1-65 mo | 2-6 mg/d (mean blood level 6 ng/mL) | 1 HUS; 1 oral carcinoma |

| Than et al[135], 2016 | German, United Kingdom | 16 AZA-NR 1 AZA-INT | Retrospective | BR in most | 60 mo | 0.5-5 mg/d | 1 LT; 4 PSC overlap |

| Al Taii et al[136], 20173 | United States | 23 second-line | Retrospective | 27% CBR 41% BR | 5 mg/d (mean) serum level: 6.7 ng/mL (mean) | Significant increase of serum creatinine; 1 discontinued for GI hemorrhage | |

| Sirolimus | |||||||

| Chatrath et al[139], 2014 | United States | 5 AZA-NR | Prospective | 4/5 BR | 4-72 mo | 2 mg/d | 2 hyperlipidemia |

| Rubin et al[141], 2016 | United States | 2 second-line | Retrospective | 1/2 BR | Not reported | 3-6 mg/d | 1 discontinued due to leg ulcer |

| Everolimus | |||||||

| Ytting et al[143], 2015 | Denmark | 7 second-line | Retrospective | 3/7 CBR 4/7 BR | 1-3 yr | 0.75-1.5 mg/d (target blood levels: 3-6 ng/mL) | Minimal |

| Rituximab | |||||||

| Burak et al[144], 2013 | Canada | 3 AZA-NR 3 AZA-INT | Prospective | 6/6 BR at 24 wk | 72 wk | 1000 mg on day 0 and 15 | 1 mild infection |

| Al-Busafi et al[182], 2013 | Oman | 1 steroid-resisitant | Retrospective | BR | Not reported | Not reported | None reported |

| Rubin et al[141], 2016 | United States | 1 second-line | Retrospective | 1/1 BR | 14 mo | 475 mg/m2 per week | None reported |

| Infliximab | |||||||

| Weiler-Normann et al[154], 2013 | Germany | 11 second-line | Retrospective | 8/11 BR | 6 to > 40 infusions | 5 mg/kg on 0, 2, 6, then every 4-8 wk | 7/11 infections, 3 discontinued for side effects |

| Vallejo et al[156], 2014 | Spain | 1 AZA-NR | Retrospective | 1/1 BR | 3 mo | 5 mg/kg given 3 times | Mild respiratory infection |

| 6-mercaptopurine | |||||||

| Pratt et al[167], 1996 | United States | 2 AZA-INT | Retrospective | 2/2 CBR, 1/2 HI | 24 mo in one not reported in the other | 100 mg/d | None reported |

| Hübener et al[168], 2016 | Germany/United Kingdom | 20 AZA-INT 2 AZA-NR | Retrospective | 8/20 CBR 7/20 BR | 18.5 mo | 25-100 mg/d | 4 discontinued for GI side-effects, 1 for leucopaenia |

| Elnegouly et al[183], 2017 | Germany/Austria | 17 AZA-INT | Retrospective | 11/12 CBR | 1 yr | 25-50 mg/d | 2 discontinued for side-effects |

| Allopurinol | |||||||

| Al-Shamma et al[170], 2013 | United Kingdom | 1 AZA-NR | Retrospective | 1/1 BR | 12 mo | 100 mg/d | None reported |

| De Boer et al[171], 2013 | The Netherlands | 3 AZA-INT 5 AZA-NR | Retrospective | 7/8 BR | 13 mo | 100 mg/d | 1 discontinued for neuropathy |

| Al-Shamma et al[172], 2013 | United Kingdom | 1 AZA-NR | Retrospective | 1/1 CBR | Not reported | 100 mg/d | None reported |

| 6-thioguanine | |||||||

| De Boer et al[174], 2005 | The Netherlands | 3 AZA-INT | Retrospective | 3/3 BR | Not reported | 0.3 mg/kg/d | None reported |

| Van den Brand et al[175], 2017 | The Netherlands | 6 AZA-NR 6 AZA-INT | Retrospective | Significant median ALT decrease | 12-75 mo | 0.3 mg/kg/d | 1 nodular regenerative hyperplasia |

The series includes 46 children (Woynarowski et al[91] 2013);

The series includes 4 adolescents, but only overall results are reported, and youngest age at diagnosis was 13 yr;

The series includes 6 adolescents, but only overall results are reported, and youngest age at diagnosis was 15 yr. BR: Biochemical response; AZA-NR: Azathioprine non-responder; AZA-INT: Azathioprine intolerant; CBR: Complete biochemical response; PDN: Prednisone; GI: Gastrointestinal; HI: Histological improvement; LT: Liver transplant; NR: Non-responder; ALT: Alanine aminotransferase; HUS: Haemolytic-uremic syndrome; PSC: Primary sclerosing cholangitis.

Though budesonide is still not recommended as first line therapy for AIH[1], it may be a valid alternative for the maintenance of remission long-time, particularly for patients experiencing steroid side effects. In a retrospective study 60 patients with either prednisolone side effects or dependence on a relative high dose of prednisolone were switched to budesonide[88]: the biochemical remission rate at 6 mo was 55%, and 25% of the patients needed to be switched back to prednisone due to budesonide side-effects or insufficient response. However, all patients who were in remission at the time of switching remained in remission. These findings indicate that budesonide is effective in maintaining remission in patients who have achieved it with prednisone, but also that it is not free of side effects, and that, not surprisingly, it is not effective in patients resistant to prednisone, as prednisone and budesonide share the same receptor.

A sub-analysis of the paediatric population (46 patients aged 9 to 17) enrolled in the budesonide trial[89] reported no significant difference in biochemical remission rate at 6 and 12 mo between the budesonide and the prednisone groups (32% and 33% at 6 mo and 50% and 42% at 12 mo, respectively) (Table 4). The frequency of steroid side effects was also not different, being 47% in the budesonide group and 63% in the prednisone group, apart from a lower mean weight gain in the budesonide group. The remission rate was well below that achieved with standard treatment, therefore, budesonide cannot be recommended for the treatment of children/adolescents with AIH until a trial including strict diagnostic criteria and drug schedules appropriate for the juvenile disease is performed[85].

Table 4.

Published data on autoimmune hepatitis treatment different from steroids and azathioprine in children

| Ref. | Country | Number and type of patients (n) | Design | Outcome | Follow-up | Dose | Side effects |

| Budesonide | |||||||

| Woynarowski et al[91], 2013 | Europe | 46 including naïve and second-line | Prospective | 16% BR AZA+BUD 15% BR AZA+PDN at 6 mo | 1 yr | 6-9 mg/d | More weight gain in PDN group |

| Mycophenolate mofetil | |||||||

| Lee et al[107], 2007 | Malaysia | 2 second-line | Retrospective | 0/2 BR at 6 mo | 6-18 mo | 20-40 mg/kg/d | Not reported |

| Aw et al[106], 2009 | United Kingdom | 20 AZA-NR 6 AZA-INT | Retrospective | 18/26 CBR | 0.75-12 mo | 20-40 mg/kg/d | 7 Leukopaenia |

| Jiménenz-Rivera et al[108], 2012 | Canada | 12 second-line | Retrospective | Not reported | Not reported | 1000-1500 mg/d | Not reported |

| Dehghani et al[109], 2013 | Iran | 5 second-line | Retrospective | 5/5 BR | None reported | Not reported | Not reported |

| Cyclosporine A | |||||||

| Jackson et al[120], 1995 | South Africa | 1 AZA-INT | Retrospective | 1/1 BR at 2 wk | 19 mo | 5 mg/kg/d | None |

| Debray et al[111], 1999 | France | 8 naïve 7 second-line (all type 2 AIH) | Retrospective | 8/8 naïve BR 7/7 second-line (including 3 with ALF) | 1-6 yr | 4.7-5.6 mg/kg/d | Minimal |

| Ben Halima et al[122], 2002 | Tunisia | 1 first-line | Retrospective | 1/1 BR | Not reported | Not reported | None |

| Sciveres et al[184], 2004 | Italy | 4 naïve 4 steroid/AZA-intolerant | Retrospective | 8/8 BR at 2-8 wk | 1.5-15 yr | 4-10 mg/kg per day | 2 gingival hypertrophy, 1 creatinine elevation |

| Cuarterolo et al[124], 2006 | Agentina | 86 naïve, type 1 AIH | Prospective | BR 94% | 2 yr | 4 mg/kg per day | 8/84 creatinine elevation 3/84 hypertension |

| Nastasio et al[115], 2011 | Italy | 19 naïve1 10 second-line1 | Retrospective | 19/19 naïve BR at 4-18 wk 9/10 second-line BR | 6.5 yr | Not reported | 11 hyperthricosis, 13 gingival hypertrophy |

| Dehghani et al[109], 2013 | Iran | 3 second-line | Retrospective | 3/3 BR | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported |

| Lee et al[107], 2015 | Malaysia | 2 second-line | Retrospective | 1 /2 BR | 6-18 mo | 5 mg/kg per day, serum level 250-350 ng/mL | |

| Zaya et al[112], 2012 | Croatia | 9 naïve (1 type 2 AIH) | Retrospective | 7/9 BR after 1 yr | 24 mo | 3-5 mg/kg per day | Minor |

| Jiménez-Rivera et al[108], 2012 | Canada | 9 naïve 15 second-line | Retrospective | Not reported | 4 ± 2 yr | 4 ± 0.8 mg/kg per day intially 4.9 ± 1.8 mg/kg per day in follow-up | Not reported |

| Tacrolimus | |||||||

| Zolfino et al[93], 2002 | United Kingdom | 1 second-line | Retrospective | NR | Not reported | 2 mg/d | Not reported |

| Marlaka et al[138], 2012 | Sweden | 20 naïve | Prospective | 3/20 BR in monotherapy | 1 yr | Target blood levels: 2.5-5 ng/ml | 1 discontinued for side-effects; 2 developed IBD |

| Dehghani et al[109], 2013 | Iran | 2 second-line | Retrospective | 2/2 BR | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported |

| Jiménez-Rivera et al[108], 2015 | Canada | 6 second-line | Retrospective | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported |

| Sirolimus | |||||||

| Kurowski et al[140], 2014 | United States | 4 second-line | Retrospective | 2/4 BR | Not reported | Not reported | 2 mo ulcers |

| Rituximab | |||||||

| D’Agostino et al[150], 2013 | Canada/Argentina | 2 second-line | Retrospective | 2/2 CBR at 3/8 mo | 26-38 mo | 375 mg/m2 weekly for 4 wk | None reported |

| Infliximab | |||||||

| Rajanayagam et al[158], 2013 | Australia | 1 second-line | Retrospective | 1/1 BR | 19 mo | 5 mg/kg 4 infusions at 4 wk interval | LT was not prevented |

| 6-mercaptopurine | |||||||

| Pratt et al[167], 1996 | United States | 1 AZA-NR | Retrospective | 1/1 CBR and HR | 36 mo | 1.5 mg/kg | None reported |

Twelve patients had additional concomintant immunosuppressive drugs. BR: Biochemical response; AZA: Azathioprine; BUD: Budesonide; PDN: Prednisone; INT: Intolerant; NR: Non-responder; AIH: Autoimmune hepatitis; ALF: Acute liver failure; IBD: Inflammatory bowel disease; LT: Liver transplant; CRB: Complete biochemical response.

Mycophenolate mofetil

Mycophenolate mofetil (MMF) is the prodrug of mycophenolic acid. It is an inhibitor of inosine monophosphate dehydrogenase, the rate-limiting enzyme in de novo purine synthesis on which, in contrast to other cells, B and T lymphocyte proliferation relies. MMF is widely used as second line AIH treatment, mostly combined with prednisone, both for patients intolerant to azathioprine and for patients with unsatisfactory response to standard azathioprine/prednisone treatment. Its use in AIH is based on retrospective series[90-103] (Table 3) with a total number of 313 patients treated, suggesting that MMF is partially effective in patients intolerant to azathioprine, but may not be effective in case of azathioprine poor response. However, a recent paper from Australia including 96 patients[104] reported a similar remission rate both in patients intolerant and poor responders to azathioprine (Table 3). One single prospective uncontrolled trial from Greece tested the use of MMF as first-line treatment[102,105] (Table 3). MMF was reported to be safe and effective in inducing and maintaining remission in treatment-naïve patients (83/102 patients achieved biochemical remission at 3 mo) and to have a rapid steroid sparing effect. However, it is not clear whether it offers an advantage over azathioprine, as a head-to-head comparison with azathioprine was not performed. A trial comparing azathioprine to MMF is currently ongoing (NCT02900443). MMF has the major disadvantages of being about 15 times more expensive than azathioprine, and, most importantly, of being teratogenic, which is highly relevant, since AIH affects mainly young females. The most frequent side effects are gastro-intestinal symptoms.

In juvenile AIH patients in whom standard immunosuppression is unable to induce stable remission, or who are intolerant to azathioprine, MMF at a dose of 20 mg/kg twice daily, together with prednisolone, has been used successfully used[90,106-108] (Table 4). A recent meta-analysis, including data from several small studies of second line treatments in children refractory to standard therapy shows that MMF is efficacious with a low side effect profile (in contrast to calcineurin inhibitors), supporting the notion that MMF should be the primary choice for second-line therapy in juvenile AIH[109].

Calcineurin inhibitors

Cyclosporine A: Cyclosporine A is a calcineurin inhibitor extensively used in the setting of transplant medicine. Important side effects are renal toxicity and cosmetic changes, particularly in association to high doses. In small retrospective series[90,108,110-115], small prospective open and uncontrolled trials[115,116] and single case studies[91,107,117-121] cyclosporine A has been reported to be effective - using variable doses, duration of treatment and follow-up - either as first-line option or in patients not responding to azathioprine and prednisone, both in children and in adults (Tables 3 and 4). Though the results of these reports appear to be encouraging, the quality and quantity of the data are insufficient to recommend its use. In paediatrics, cyclosporine A has been used as first line treatment for type 1 AIH in an attempt to reduce steroid side effects in a prospective multicentre study in 84 treatment-naïve children[122,123] (Table 4). Cyclosporine alone was administered for 6 mo, and the patients were subsequently switched to azathioprine and prednisone. Transaminase levels normalization was obtained in 72% of the subjects after six months of cyclosporine monotherapy, but IgG levels were not included in the remission criteria. Cyclosporine side effects included hypertrichosis (55%), gingival hyperplasia (39%), elevation of creatinine (9%) and hypertension (3%). The main limitation of this study is lack of direct comparison with standard treatment.

Animal data suggest that cyclosporine A may promote autoimmunity[124-127], and the first reports of de novo autoimmune hepatitis arising after liver transplantation were in children treated with cyclosporine[128]. These observations call for caution in the use of cyclosporine in AIH.

Tacrolimus: Tacrolimus is a more potent calcineurin inhibitor than cyclosporine, has less cosmetic side effects, but similar drug class toxicity. In AIH, it has been used both for refractory cases and for patients intolerant to other immunosuppressive regimens. A few retrospective small case series in adults have been published, with variable remission criteria, sometimes including only transaminase levels[91,93,129-135]. The reported efficacy was good in a total number of 80 patients (Table 3). Two prospective open-label trials from the ‘90s are available, both in naïve patients[133,136] (Table 3). The oldest one included 21 adult patients[133], with a follow up of 1 year, after which a liver biopsy was repeated, but histological results are not reported. Half of the patients were anti-LKM1 positive; tacrolimus was used as monotherapy. Of note, the serum target level of tacrolimus was low (0.6-1 ng/mL). The mean decrease of transaminase and bilirubin levels was satisfactory, but the remission rate is not reported. In terms of side effects, the mean creatinine value increased significantly after 1 year of treatment. The second prospective trial in naïve patients included seven adult subjects and used lower tacrolimus doses combined with 20 mg/d of prednisolone. Transaminase levels, albumin, bilirubin and prothrombin time significantly improved in 6/7 patients[136].

In children, one prospective, single centre, open label trial including 20 treatment naïve patients is available: none was anti-LKM1 positive, follow up was 1 year, after which a liver biopsy was repeated[137] (Table 4). Target tacrolimus blood levels were 2.5-5 ng/mL. 14/20 patients needed azathioprine and prednisone in addition to tacrolimus to achieve remission. Histological improvement of inflammation was seen in 12/14 cases. No effect on the renal function was observed. This trial suggests that tacrolimus as monotherapy is not effective in juvenile AIH, but could be considered as steroid/azathioprine sparing agent.

More high-quality data are needed, both in adults and children, to assess tacrolimus efficacy in AIH.

m-TOR inhibitors

Sirolimus: Sirolimus is a macrolide molecule acting by inhibiting the mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR), a protein that modulates the proliferation and survival of activated lymphocytes. It is produced by the bacterium Streptomyces hygroscopicus and was isolated in 1972 on Easter Island (Rapa Nui). Sirolimus is used to prevent rejection in solid organ transplantion.

There is very limited experience in the use of this drug for poor responders to standard AIH treatment. Retrospective data on 5 adult patients with AIH refractory to prednisone, azathioprine and mycophenolate are available[138] (Table 3). Only transaminase levels were used to define remission, median follow up was 24 mo, the target serum level was low, 10-20 ng/dL. Complete remission was achieved in 2/5 patients. Side effects were limited to hyperlipidaemia occurring in 2/5 patients. In paediatrics, a small retrospective series reports the use of rapamycin in 5 cases refractory to standard treatment (3/4 also to MMF)[139], including 1 case of non-adherence (Table 4). Two of the four patients showed an improvement in transaminase levels; tolerability was good, though 2/4 had mouth ulcerations not requiring drug discontinuation. The target sirolimus blood levels reported in the paper are 4-8 ng/mL. A report of two additional adult cases of difficult-to-treat AIH patients managed with sirolimus is even less encouraging: in one case sirolimus was discontinued due to legs ulcers, and in the other it was ineffective[140]. No drug serum levels were reported.

In conclusion, data on sirolimus in difficult-to-treat AIH patients are scanty and rather disappointing.

In the transplant setting, sirolimus has been reported to be effective in difficult-to-treat de novo AIH or AIH recurrence[141] in a small series of 6 paediatric patients. Three of them experienced infections while on sirolimus, including one case of colitis and fever leading to drug discontinuation.

Everolimus: Everolimus has a mechanism of action similar to sirolimus, and is used to prevent solid organ rejection, or at higher doses, as an anti-cancer drug.

Only one report is available on the use of everolimus for the treatment of AIH. It is a retrospective series of 7 adult patients with insufficient response to standard or alternative treatments (budesonide, MMF, calcineurin inhibitors), or with severe treatment side-effects[142] (Table 3). Everolimus target blood concentration was 3-6 ng/mL. Complete biochemical response was obtained in 3/7 patients after 5 mo, but all patients, except one who was non-adherent, had significant decrease in serum transaminase levels, allowing reduction of the steroid dose. Histology did not show disease progression in four patients treated for 3-5 years. No severe side effects were reported, but one patient died from cholangiocarcinoma diagnosed 6 mo after starting everolimus, though cancer was not considered to be associated with the drug. In conclusion, in view of the very few data available, the role of everolimus in the treatment of AIH remains to be explored.

Biologicals

Rituximab: Rituximab is a monoclonal chimaeric (murine/human) antibody that specifically binds the CD-20 antigen, a phosphoprotein expressed on the surface of B-lymphocytes, leading to B-cell depletion. It is approved for the treatment of non-Hodgkin lymphoma, rheumatoid arthritis and ANCA-associated vasculitis. It has also been used recently as rescue treatment in refractory AIH. In a single-centre open-label pilot study in Canada, 6 AIH adult patients who had failed treatment with prednisone and/or azathioprine[143] for intolerable side-effects (3/6) or refractory disease (3/6) were treated with two doses of 1000 mg rituximab administered two weeks apart (Table 3). Tolerance was good, only one patient developing minor infections. In all patients, transaminase and IgG levels decreased; a liver biopsy performed after 1 year in 4 of the 6 patients showed improvement of the inflammatory activity. Though a recent survey shows that rituximab is used for difficult-to-treat AIH patients in several centres[144], this experience has not been published. A few case reports of patients with AIH coexisting with other autoimmune diseases have been published[145-149], all demonstrating a positive effect of rituximab also on AIH.

In children, two cases of refractory AIH have been successfully treated with rituximab[149] (Table 4). In addition, the recently published preliminary results of a real-world expert management of paediatric AIH also reported the use of rituximab as rescue therapy[150].

In summary, rituximab has shown good efficacy in a small number of difficult-to-treat AIH patients, but its safety profile needs to be evaluated carefully, as the drug may have severe long term side-effects, including B-cell depletion[151].

Infliximab: Infliximab is a recombinant humanized chimaeric antibody used for the treatment of ulcerative colitis, Crohn disease, rheumatoid arthritis, psoriatic arthritis/plaque psoriasis, and ankylosing spondylitis. It acts mainly by direct neutralization of soluble tumour necrosis factor-alpha, but it has also pro-apoptotic and anti-proliferative effects on lymphocytes[152].

One small retrospective series from Germany on the use of infliximab as salvage therapy in 11 adult AIH patients reports[153] (Table 3) normalisation of transaminase levels in 8 and of IgG levels in 6. However, 7 patients developed infectious complications, and treatment had to be stopped because of side effects in three cases. Recently, preliminary results of an extension of this cohort of difficult-to-treat AIH patients was published: the cohort now includes 18 cases, 15 reaching biochemical remission[154]. Two case reports have also been published: one describing a difficult-to-treat AIH patient who achieved normalization of transaminases levels after 3 mo of infliximab treatment[155], and one reporting good disease control on infliximab in a young patient with AIH and adult onset Still disease[156].

In children, a 10-year old girl with aggressive disease, unresponsive to standard treatment, MMF and tacrolimus, has been reported to have a good response to infliximab, though liver transplantation was deferred but not avoided[157] (Table 4).

As for rituximab, specialized centres have unreported experience[144,150]. It is important to note that anti-tumour necrosis factor-alpha can induce hepatotoxicity resembling AIH[158-162], as well as other immune-mediated disorders, such as lupus erythematosus[163]. This should raise caution in using this agent, which should be reserved for treatement–resistant AIH cases in specialised centres.

Thiopurines

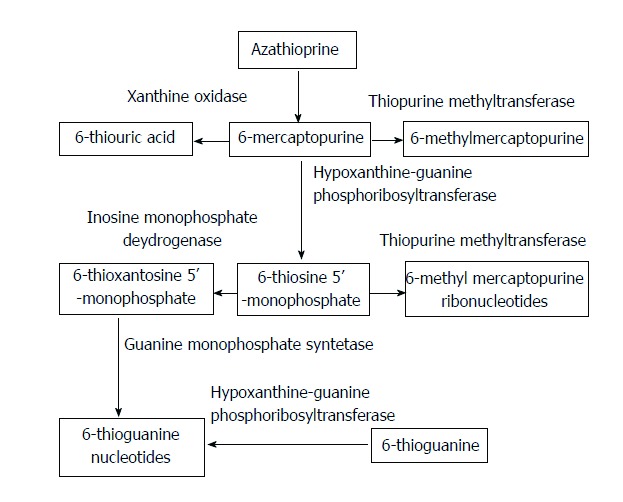

6-mercaptopurine: Azathioprine is the prodrug of 6-mercaptopurine (6-MP), and is non-enzymatically converted into 6-MP, which represents the biologically active form of the drug. 6-MP is used for the treatment of IBD, where it has been shown that 6-MP is better tolerated than azathioprine[164,165], despite the close biochemical relationship and shared metabolic pathways (Figure 2). In AIH, 6-MP was used successfully in 3 patients intolerant or unresponsive to azathioprine, including one paediatric patient[166], representing the only published experience in children (Tables 3 and 4). The largest series of AIH patients intolerant or unresponsive to standard treatment switched to 6-MP is a retrospective study on 22 adult cases[167] (Table 3). The two patients with insufficient response to standard treatment did not respond to 6-MP, whereas 15/20 patients intolerant to azathioprine showed either partial (7/15) or complete (8/15) biochemical remission. Five patients discontinued 6-MP, four for gastrointestinal side effects, and one for leukopaenia. Recently, preliminary data from an additional multicentre retrospective series of 17 patients, all azathioprine-intolerant, reported complete biochemical response in 11 of the 12 patients followed-up for at least 12 mo[168]. These data suggest that 6-MP can be an alternative for patients intolerant to azathioprine, but the available data are insufficient to formulate recommendations.

Figure 2.

Simplified representation of the thiopurine metabolism. Azathioprine is non-enzymatically converted to 6-mercaptopurine, which is competitively converted into 6-methymercaptopurine, 6-thiouric acid and 6-thiosine 5’-monophosphate by different enzymes. The latter metabolite is further transformed into the metabolic active 6-thioguanine nucleotides.

Allopurinol: Azathioprine hepatotoxicity can be due to a skewed metabolism of the drug, leading to a preferential generation of the hepatotoxic metabolite 6-methylmercaptopurine (6-MMP) instead of the metabolic active 6-thioguanine nucleotides (6-TGN). Allopurinol co-administration redirects the thiopurine metabolism towards 6-TGN. This strategy is used in the treatment of IBD. A case report suggests that allopurinol can be helpful also in AIH[169] (Table 3). A retrospective case-series of 8 AIH adult patients intolerant or with insufficient response either to azathioprine/prednisone (4/8) or 6-MP/prednisone (4/8), one patient in each group being also on budesonide, reported complete biochemical remission in 3/3 intolerant patients and in 4/5 unresponsive patients[170] (Table 3). All patients had skewed thiopurine metabolism. In one further case report of a patient with insufficient response to prednisone/azathioprine and shunted metabolism, allopurinol (100 mg/d) allowed rapid normalisation of transaminase levels and steroid reduction[171] (Table 3).

6-thioguanine: 6-thioguanine (6-TG) is enzymatically converted into 6-TGN, which are the active metabolites of azathioprine, bypassing the metabolic steps leading to the formation of the hepatotoxic metabolite 6-MMP (Figure 2). 6-TG is approved for the treatment of acute and chronic myeloid leukaemia, and chronic lymphatic leukaemia. It is used in IBD patients with insufficient response or intolerant to azathioprine or 6-MP[172]. Safety issues have been raised, particularly in respect to the development of nodular regenerative hyperplasia and sinusoidal obstruction syndrome[172]. In AIH, after an early preliminary report[173], a retrospective series of 12 adult patients switched from azathioprine or 6-MP to 6-TG for intolerance or insufficient response reported a median alanine aminotransferase levels drop from 81 IU/L to 30 IU/L (Table 3). Nodular regenerative hyperplasia developed in one case after 8 years of 6-TG treatment[174].

Due to the paucity of data and its potential hepatotoxicity, 6-TG cannot be recommended in AIH.

TREATMENTS UNDER INVESTIGATION

New compounds are currently under investigation in AIH. Preliminary results of a phase 1, first-in-human trial of preimplantation factor in AIH demonstrated good safety and tolerability, but a non-significant decrease in mean transaminase levels[175]. Other investigational drugs in AIH include VAY736, which leads to B-cell depletion and B-cell activating factor receptor blockade (NCT03217422), JKB-122, which is a toll-like receptor 4 antagonist (NCT02556372) and low dose interleukin 2 (NCT01988506).

CONCLUSION

The pharmacological treatment of AIH should be personalized, because of the heterogeneity of the disease. Treatment schedules in children differ, because of the more aggressive disease course in this age group. Standard treatment, based on steroids and azathioprine, is effective in the vast majority of patients, and side-effects can be minimised by rapid prednisone tapering. Budesonide was tried as first-line treatment in an attempt to reduce steroids side-effects, but the results of a randomized controlled trial do not allow to universally recommending it as first-line treatment instead of prednisone. A minority of patients prove difficult-to-treat, either because of severe side effects from standard treatment, or resistant disease. Mycophenolate mofetil is the most widely used second-line drug, and also the drug with the highest amount of available data. Calcineurin inhibitors are alternative options, but data on their efficacy are scanty. Infliximab and rituximab may represent an additional treatment option for selected difficult-to treat cases, but their use should be restricted to specialised centres because of potentially severe side effects. New pharmaceutical treatments are currently under investigation.

Footnotes

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: United Kingdom

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B, B, B, B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

Conflict-of-interest statement: No potential conflicts of interest.

Peer-review started: June 7, 2017

First decision: June 22, 2017

Article in press: August 2, 2017

P- Reviewer: Dehghani S, Drenth JPH, Lee HC, Rodrigues AT, Watanabe T, Wirth S S- Editor: Ma YJ L- Editor: A E- Editor: Xu XR

Contributor Information

Benedetta Terziroli Beretta-Piccoli, Epatocentro Ticino, 6900 Lugano, Switzerland.

Giorgina Mieli-Vergani, Paediatric Liver, GI and Nutrition Centre, MowatLabs, King’s College Hospital, Denmark Hill, London SE5 9RS, United Kingdom.

Diego Vergani, Institute of Liver Studies, MowatLabs, King’s College Hospital, Denmark Hill, London SE5 9RS, United Kingdom. diego.vergani@kcl.ac.uk.

References

- 1.European Association for the Study of the Liver. EASL Clinical Practice Guidelines: Autoimmune hepatitis. J Hepatol. 2015;63:971–1004. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2015.06.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Manns MP, Czaja AJ, Gorham JD, Krawitt EL, Mieli-Vergani G, Vergani D, Vierling JM; American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. Diagnosis and management of autoimmune hepatitis. Hepatology. 2010;51:2193–2213. doi: 10.1002/hep.23584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vergani D, Mackay IR, Mieli-Vergani G. The Autoimmune Diseases (Fifth Edition) Boston: Academic Press;; 2014. Chapter 61 - Hepatitis [Internet] pp. [cited 2016 Oct 15]. page 889–907. Available from: http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/B9780123849298000617. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Longhi MS, Ma Y, Mieli-Vergani G, Vergani D. Aetiopathogenesis of autoimmune hepatitis. J Autoimmun. 2010;34:7–14. doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2009.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Liberal R, Krawitt EL, Vierling JM, Manns MP, Mieli-Vergani G, Vergani D. Cutting edge issues in autoimmune hepatitis. J Autoimmun. 2016;75:6–19. doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2016.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Johnson PJ, McFarlane IG. Meeting report: International Autoimmune Hepatitis Group. Hepatology. 1993;18:998–1005. doi: 10.1002/hep.1840180435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Alvarez F, Berg PA, Bianchi FB, Bianchi L, Burroughs AK, Cancado EL, Chapman RW, Cooksley WG, Czaja AJ, Desmet VJ, et al. International Autoimmune Hepatitis Group Report: review of criteria for diagnosis of autoimmune hepatitis. J Hepatol. 1999;31:929–938. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(99)80297-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hennes EM, Zeniya M, Czaja AJ, Parés A, Dalekos GN, Krawitt EL, Bittencourt PL, Porta G, Boberg KM, Hofer H, et al. Simplified criteria for the diagnosis of autoimmune hepatitis. Hepatology. 2008;48:169–176. doi: 10.1002/hep.22322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Muratori P, Granito A, Pappas G, Muratori L. Validation of simplified diagnostic criteria for autoimmune hepatitis in Italian patients. Hepatology. 2009;49:1782–1783; author reply 1783. doi: 10.1002/hep.22825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Muñoz-Espinosa L, Alarcon G, Mercado-Moreira A, Cordero P, Caballero E, Avalos V, Villarreal G, Senties K, Puente D, Soto J, et al. Performance of the international classifications criteria for autoimmune hepatitis diagnosis in Mexican patients. Autoimmunity. 2011;44:543–548. doi: 10.3109/08916934.2011.592884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Qiu D, Wang Q, Wang H, Xie Q, Zang G, Jiang H, Tu C, Guo J, Zhang S, Wang J, et al. Validation of the simplified criteria for diagnosis of autoimmune hepatitis in Chinese patients. J Hepatol. 2011;54:340–347. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2010.06.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vergani D, Mieli-Vergani G. Pharmacological management of autoimmune hepatitis. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2011;12:607–613. doi: 10.1517/14656566.2011.524206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kirk AP, Jain S, Pocock S, Thomas HC, Sherlock S. Late results of the Royal Free Hospital prospective controlled trial of prednisolone therapy in hepatitis B surface antigen negative chronic active hepatitis. Gut. 1980;21:78–83. doi: 10.1136/gut.21.1.78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Al-Chalabi T, Boccato S, Portmann BC, McFarlane IG, Heneghan MA. Autoimmune hepatitis (AIH) in the elderly: a systematic retrospective analysis of a large group of consecutive patients with definite AIH followed at a tertiary referral centre. J Hepatol. 2006;45:575–583. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2006.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Czaja AJ. Clinical Features, Differential Diagnosis and Treatment of Autoimmune Hepatitis in the Elderly. Drugs Aging. 2012;25:219–239. doi: 10.2165/00002512-200825030-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Czaja AJ, Carpenter HA. Distinctive clinical phenotype and treatment outcome of type 1 autoimmune hepatitis in the elderly. Hepatology. 2006;43:532–538. doi: 10.1002/hep.21074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Floreani A, Liberal R, Vergani D, Mieli-Vergani G. Autoimmune hepatitis: Contrasts and comparisons in children and adults - a comprehensive review. J Autoimmun. 2013;46:7–16. doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2013.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Muratori L, Muratori P, Lanzoni G, Ferri S, Lenzi M. Application of the 2010 American Association for the study of liver diseases criteria of remission to a cohort of Italian patients with autoimmune hepatitis. Hepatology. 2010;52:1857; author reply 1857–1857; author reply 1858. doi: 10.1002/hep.23924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kerkar N, Annunziato RA, Foley L, Schmeidler J, Rumbo C, Emre S, Shneider B, Shemesh E. Prospective analysis of nonadherence in autoimmune hepatitis: a common problem. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2006;43:629–634. doi: 10.1097/01.mpg.0000239735.87111.ba. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gregorio GV, Portmann B, Reid F, Donaldson PT, Doherty DG, McCartney M, Mowat AP, Vergani D, Mieli-Vergani G. Autoimmune hepatitis in childhood: a 20-year experience. Hepatology. 1997;25:541–547. doi: 10.1002/hep.510250308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lamers MM, van Oijen MG, Pronk M, Drenth JP. Treatment options for autoimmune hepatitis: A systematic review of randomized controlled trials. J Hepatol. 2010;53:191–198. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2010.01.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cook GC, Mulligan R, Sherlock S. Controlled prospective trial of corticosteroid therapy in active chronic hepatitis. Q J Med. 1971;40:159–185. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.qjmed.a067264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Soloway RD, Summerskill WH, Baggenstoss AH, Geall MG, Gitnićk GL, Elveback IR, Schoenfield LJ. Clinical, biochemical, and histological remission of severe chronic active liver disease: a controlled study of treatments and early prognosis. Gastroenterology. 1972;63:820–833. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Murray-Lyon IM, Stern RB, Williams R. Controlled trial of prednisone and azathioprine in active chronic hepatitis. Lancet. 1973;1:735–737. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(73)92125-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lohse AW, Mieli-Vergani G. Autoimmune hepatitis. J Hepatol. 2011;55:171–182. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2010.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Summerskill WH, Korman MG, Ammon HV, Baggenstoss AH. Prednisone for chronic active liver disease: dose titration, standard dose, and combination with azathioprine compared. Gut. 1975;16:876–883. doi: 10.1136/gut.16.11.876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tage-Jensen U, Schlichting P, Aldershvile J, Andersen P, Dietrichson O, Hardt F, Mathiesen LR, Nielsen JO. Azathioprine versus prednisone in non-alcoholic chronic liver disease (CLD). Relation to a serological classification. Liver. 1982;2:95–103. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0676.1982.tb00184.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kil JS, Lee JH, Han A-R, Kang JY, Won HJ, Jung HY, Lim HM, Gwak G-Y, Choi MS, Koh KC, et al. Long-term Treatment Outcomes for Autoimmune Hepatitis in Korea. J Korean Med Sci. 2010;25:54–60. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2010.25.1.54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bruguera M, Caballería L, Parés A, Rodés J. [Autoimmune hepatitis. Clinical characteristics and response to treatment in a series of 49 spanish patients] Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1998;21:375–381. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Seela S, Sheela H, Boyer JL. Autoimmune hepatitis type 1: safety and efficacy of prolonged medical therapy. Liver Int. 2005;25:734–739. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2005.01141.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Valera JM, Smok G, Márquez S, Poniachik J, Brahm J. [Histological regression of liver fibrosis with immunosuppressive therapy in autoimmune hepatitis] Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;34:10–15. doi: 10.1016/j.gastrohep.2010.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Maggiore G, Bernard O, Hadchouel M, Hadchouel P, Odievre M, Alagille D. Treatment of autoimmune chronic active hepatitis in childhood. J Pediatr. 1984;104:839–844. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(84)80477-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Johnson PJ, McFarlane IG, Williams R. Azathioprine for long-term maintenance of remission in autoimmune hepatitis. N Engl J Med. 1995;333:958–963. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199510123331502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Banerjee S, Rahhal R, Bishop WP. Azathioprine monotherapy for maintenance of remission in pediatric patients with autoimmune hepatitis. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2006;43:353–356. doi: 10.1097/01.mpg.0000232331.93052.dd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sheiko MA, Sundaram SS, Capocelli KE, Pan Z, McCoy AM, Mack CL. Outcomes in Pediatric Autoimmune Hepatitis and Significance of Azathioprine Metabolites. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2017;65:80–85. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0000000000001563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Enweluzo C, Aziz F, Mori A. Comparing efficacy between regimens in the initial treatment of autoimmune hepatitis. J Clin Med Res. 2013;5:281–285. doi: 10.4021/jocmr1486w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Stellon AJ, Keating JJ, Johnson PJ, McFarlane IG, Williams R. Maintenance of remission in autoimmune chronic active hepatitis with azathioprine after corticosteroid withdrawal. Hepatology. 1988;8:781–784. doi: 10.1002/hep.1840080414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Maggiore G, Veber F, Bernard O, Hadchouel M, Homberg JC, Alvarez F, Hadchouel P, Alagille D. Autoimmune hepatitis associated with anti-actin antibodies in children and adolescents. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 1993;17:376–381. doi: 10.1097/00005176-199311000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Karakoyun M, Ecevit CO, Kilicoglu E, Aydogdu S, Yagci RV, Ozgenc F. Autoimmune hepatitis and long-term disease course in children in Turkey, a single-center experience. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;28:927–930. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0000000000000648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Samaroo B, Samyn M, Buchanan C, Mieli-vergani G. Long-term Daily Oral Treatment With Prednisolone In Children With Autoimmune Liver Disease Does Not Affect Final Adult Height. Hepatology [Internet] 2006 [cited 2017 Jan 6] Available from: http://insights.ovid.com/hepatology/hepa/2006/10/001/long-term-daily-oral-treatment-prednisolone/670/01515467. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mieli-Vergani G, Heller S, Jara P, Vergani D, Chang MH, Fujisawa T, González-Peralta RP, Kelly D, Mohan N, Shah U, et al. Autoimmune hepatitis. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2009;49:158–164. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0b013e3181a1c265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dumortier J, Arita CT, Rivet C, LeGall C, Bouvier R, Fabien N, Guillaud O, Collardeau-Frachon S, Scoazec JY, Lachaux A. Long-term treatment reduction and steroids withdrawal in children with autoimmune hepatitis: a single centre experience on 55 children. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;21:1413–1418. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0b013e32832ad5f7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kanzler S, Löhr H, Gerken G, Galle PR, Lohse AW. Long-term management and prognosis of autoimmune hepatitis (AIH): a single center experience. Z Gastroenterol. 2001;39:339–341, 344-348. doi: 10.1055/s-2001-13708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Czaja AJ. Safety issues in the management of autoimmune hepatitis. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2008;7:319–333. doi: 10.1517/14740338.7.3.319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Langley PG, Underhill J, Tredger JM, Norris S, McFarlane IG. Thiopurine methyltransferase phenotype and genotype in relation to azathioprine therapy in autoimmune hepatitis. J Hepatol. 2002;37:441–447. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(02)00214-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Heneghan MA, Allan ML, Bornstein JD, Muir AJ, Tendler DA. Utility of thiopurine methyltransferase genotyping and phenotyping, and measurement of azathioprine metabolites in the management of patients with autoimmune hepatitis. J Hepatol. 2006;45:584–591. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2006.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Newman WG, Payne K, Tricker K, Roberts SA, Fargher E, Pushpakom S, Alder JE, Sidgwick GP, Payne D, Elliott RA, et al. A pragmatic randomized controlled trial of thiopurine methyltransferase genotyping prior to azathioprine treatment: the TARGET study. Pharmacogenomics. 2011;12:815–826. doi: 10.2217/pgs.11.32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Brinkert F, Arrenberg P, Krech T, Grabhorn E, Lohse A, Schramm C. Two Cases of Hepatosplenic T-Cell Lymphoma in Adolescents Treated for Autoimmune Hepatitis. Pediatrics. 2016;138:e20154245. doi: 10.1542/peds.2015-4245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Aggarwal N, Chopra S, Suri V, Sikka P, Dhiman RK, Chawla Y. Pregnancy outcome in women with autoimmune hepatitis. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2011;284:19–23. doi: 10.1007/s00404-010-1540-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Heneghan MA, Norris SM, O’Grady JG, Harrison PM, McFarlane IG. Management and outcome of pregnancy in autoimmune hepatitis. Gut. 2001;48:97–102. doi: 10.1136/gut.48.1.97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Terrabuio DR, Abrantes-Lemos CP, Carrilho FJ, Cançado EL. Follow-up of pregnant women with autoimmune hepatitis: the disease behavior along with maternal and fetal outcomes. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2009;43:350–356. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0b013e318176b8c5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hindorf U, Jahed K, Bergquist A, Verbaan H, Prytz H, Wallerstedt S, Werner M, Olsson R, Björnsson E, Peterson C, et al. Characterisation and utility of thiopurine methyltransferase and thiopurine metabolite measurements in autoimmune hepatitis. J Hepatol. 2010;52:106–111. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2009.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rumbo C, Emerick KM, Emre S, Shneider BL. Azathioprine metabolite measurements in the treatment of autoimmune hepatitis in pediatric patients: a preliminary report. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2002;35:391–398. doi: 10.1097/00005176-200209000-00032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hartl J, Ehlken H, Weiler-Normann C, Sebode M, Kreuels B, Pannicke N, Zenouzi R, Glaubke C, Lohse AW, Schramm C. Patient selection based on treatment duration and liver biochemistry increases success rates after treatment withdrawal in autoimmune hepatitis. J Hepatol. 2015;62:642–646. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2014.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.van Gerven NM, Verwer BJ, Witte BI, van Hoek B, Coenraad MJ, van Erpecum KJ, Beuers U, van Buuren HR, de Man RA, Drenth JP, et al. Relapse is almost universal after withdrawal of immunosuppressive medication in patients with autoimmune hepatitis in remission. J Hepatol. 2013;58:141–147. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2012.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kanzler S, Gerken G, Dienes HP, Meyer zum Büschenfelde KH, Lohse AW. Cyclophosphamide as alternative immunosuppressive therapy for autoimmune hepatitis--report of three cases. Z Gastroenterol. 1997;35:571–578. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Burak KW, Urbanski SJ, Swain MG. Successful treatment of refractory type 1 autoimmune hepatitis with methotrexate. J Hepatol. 1998;29:990–993. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(98)80128-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sultan MI, Biank VF, Telega GW. Successful treatment of autoimmune hepatitis with methotrexate. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2011;52:492–494. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0b013e3181f3d9c0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Venkataramani A, Jones MB, Sorrell MF. Methotrexate therapy for refractory chronic active autoimmune hepatitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:3432–3434. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2001.05346.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Miyake Y, Iwasaki Y, Kobashi H, Yasunaka T, Ikeda F, Takaki A, Okamoto R, Takaguchi K, Ikeda H, Makino Y, et al. Efficacy of ursodeoxycholic acid for Japanese patients with autoimmune hepatitis. Hepatol Int. 2009;3:556–562. doi: 10.1007/s12072-009-9155-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Czaja AJ, Carpenter HA, Lindor KD. Ursodeoxycholic acid as adjunctive therapy for problematic type 1 autoimmune hepatitis: a randomized placebo-controlled treatment trial. Hepatology. 1999;30:1381–1386. doi: 10.1002/hep.510300603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]