Abstract

Cutaneous endometriosis is defined by the presence of endometrial glands and/or stroma in skin and represents less than 1% of all ectopic endometrium. Cutaneous endometriosis is classified as primary and secondary. Primary cutaneous endometriosis appears without a prior surgical history and secondary cutaneous endometriosis mostly occurs at surgical scar tissue after abdominal operations. The most widely accepted pathogenesis of secondary endometriosis is the iatrogenic implantation of endometrial cells after surgery, such as laparoscopic procedures. However, the pathogenesis of primary endometriosis is still unknown. Umbilical endometriosis is composed only 0.4% to 4.0% of all endometriosis, however, umbilicus is the most common site of primary cutaneous endometriosis. A 38-year-old women presented with solitary 2.5×2.0-cm-sized purple to brown colored painful nodule on the umbilicus since 2 years ago. The patient had no history of surgical procedures. The skin lesion became swollen with spontaneous bleeding during menstruation. The skin lesion was diagnosed as a keloid at private hospital and has been treated with lesional injection of steroid for several times but there was no improvement. Imaging studies showed an enhancing umbilical mass without connection to internal organs. Biopsy specimen showed the several dilated glandular structures in dermis. They were surrounded by endometrial-type stroma and perivascular infiltration of lymphocytes. The patient was diagnosed as primary cutaneous endometriosis and skin lesion was removed by complete wide excision without recurrence. We report an interesting and rare case of primary umbilical endometriosis mistaken for a keloid and review the literatures.

Keywords: Cutaneous endometriosis, Endometriosis of umbilicus, Primary cutaneous endometriosis, Umbilical endometriosis

INTRODUCTION

Endometriosis is histopathologically defined by the presence of endometrial glands and/or stroma outside of the endometrium1. Ectopic endometriosis could be developed in many other tissues, most commonly affects pelvic organs such as ovaries, fallopian tubes, uterine ligaments, pelvic wall2. Primary cutaneous umbilical endometriosis, which is also known as Villar's nodule, is a rare manifestation of endometriosis3. Secondary endometriosis mostly occurs at surgical scar tissue after abdominal operations4. The most widely accepted pathogenesis of secondary endometriosis is the iatrogenic implantation of endometrial cells after surgery, commonly after laparoscopic procedures5. However, the pathogenesis of primary endometriosis is still unknown.

To date, umbilical endometriosis has been reported to represent about 0.4% to 4.0% of all endometriosis and accounts for 30% to 40% cases of cutaneous endometriosis. Among cutaneous endometriosis, primary umbilical endometriosis was considered even less common.

CASE REPORT

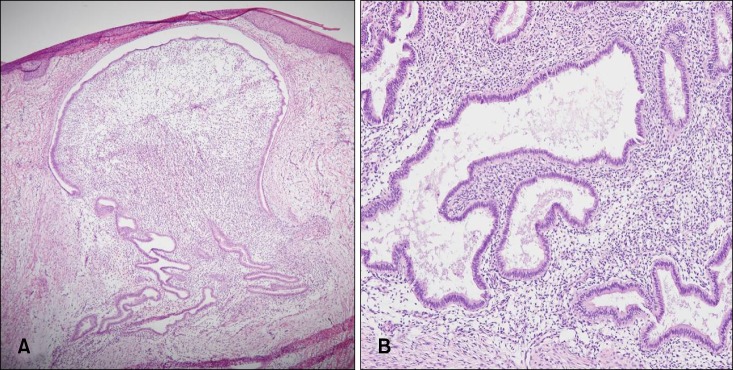

A 38-year-old multigravida female visited our department because of a painful nodule on her umbilicus. The patient recalled that the lesion was observed 2 years ago and the lesion became swollen with spontaneous frank bleeding during menstruation. The patient had no history of surgical procedure, nor any family history of malignancy. The nodule was first diagnosed as a keloid at a private clinic and had been treated with intralesional injection of steroid for several times without any signs of improvement. Physical examination revealed a 2.5×2.0-cm-sized brownish to purple colored nodule on the umbilicus (Fig. 1). Imaging studies were carried out for differential diagnosis with Sister Mary Joseph nodule and keloid. Umbilical ultrasonography showed a mass with heterogenous echogenecity, increased vascularity and abdominal computed tomography (CT) revealed enhancing mass at umbilicus without connection to abdominal organs. Histopathological examination showed dilated glandular structures surrounded by cellular endometrial-type stroma and deep perivascular infiltration of lymphocytes (Fig. 2). According to these findings, the umbilical lesion was diagnosed as primary cutaneous endometriosis and it was removed by local surgical excision. Postoperative period was unremarkable and the patient was followed up for 2 years without recurrence.

Fig. 1. About 2.5×2.0-cm-sized brownish to purple colored nodule on the umbilicus.

Fig. 2. (A, B) Specimen showed lesions in the superficial dermis and deep dermis comprising dilated glandular structures, surrounded by cellular endometrial-type stroma (H&E; A: ×40, B: ×100, respectively).

DISCUSSION

Cutaneous endometriosis represents 0.5% to 1.0% of all patients with ectopic endometriosis. Less than 30% of cutaneous endometriosis presents without prior surgical operative history, which is termed as primary spontaneous cutaneous endometriosis3. Umbilical endometriosis is composed 0.4% to 4.0% of all endometriosis, high as two-fifths of extragenital endometrioric lesions. Moreover, umbilicus is the most common site of primary cutaneous endometriosis6. Umbilical endometriosis occurs in female of reproductive age and associated symptoms are cyclic pain, bleeding and swelling of the lesion according to the menstrual cycle4.

Several possible pathogenesis of umbilical endometriosis were suggested by multiple investigators. The most commonly accepted mechanisms are lymphatic or vascular migration, cellular metaplasia, and iatrogenic metastasis5. Suggested theory includes migration of endometrial tissue from retrogression of menstruation. Survival of endometrial implants after implantation may depend on local and systemic factors. Inflammatory process is then stimulated by microvascular endothelial injury. Accordingly, it might enhance adhesion of tissue implants in outside of endometrial tissues via production of adhesion molecules such as integrin and e-cadherins7. Major etiologic pathogenesis of secondary umbilical endometriosis could be explained by iatrogenic metastasis, endometrial cells implant in scars after surgery. In comparison, primary umbilical endometriosis may be explained by the theory of vascular or lymphatic migration.

Twenty-nine published studies with primary umbilical endometriosis were identified in the literature written in English and Korean language during the period 2000~2016 (Table 1)1,3,4,5,6,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30. Primary umbilical endometriosis is initially very rare condition, but it is now increasing in number. Based on all the reports, the mean age of patients was 35.1 years.

Table 1. Literature review of primary umbilical endometriosis.

| Reference | Age at diagnosis (yr) | Age at initial (yr) | Initial diagnosis | Presenting symptom | Treatment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Theunissen and IJpma9 | 47 | 47 | Umbilical hernia | Asymptomatic umbilical nodule | Surgical excision |

| Calagna et al.10 | 33 | 33 | Umbilical granuloma | Spontaneous catamenial bleeding | Surgical excision |

| Chikazawa et al.11 | 46 | 44 | Swelling during mentrual period | Surgical excision | |

| Chikazawa et al.11 | 27 | 23 | Pain during menstrual period | Surgical excision | |

| Pariza and Mavrodin12 | 26 | 25 | Pain and discharge | Surgical excision | |

| Paramythiotis et al.13 | 46 | - | Uterine leiomyoma | Abdominal and pelvic pain | Total hysterectomy with excision of nodule |

| Ghosh and Das14 | 33 | 33 | Umbilical endometriosis | Cyclic pain and swelling | Excisional biopsy |

| Gin et al.15 | 31 | 31 | Swelling during mentrual period | Surgical excision | |

| Kahlenberg and Laskey16 | 24 | 20 | Abcess | Bloody discharge during menstrual period | Surgical excision |

| Fancellu et al.17 | 24 | 24 | Umbilical endometriosis | Concomittant bleeding on menstruation | Surgical excision |

| Jaime et al.3 | 33 | 33 | Spontaneous bleeding | Not described | |

| Efremidou et al.18 | 44 | 38~39 | Granuloma | Pain during menstrual period | Surgical excision |

| Kesici et al.19 | 38 | 38 | Omphalitis | Umbilical secretion and mass | Surgical excision |

| Fernández-Aceñero and Córdova4 | 38 | 35 | Umbilical endometriosis with uterine fibroids | Cyclic pain | Abdominal hysterectomy with excision of nodule |

| Dadhwal et al.8 | 42 | 42 | Cyclic pain and blackish discoloration | Surgical excision | |

| Bagade and Guirguis20 | 35 | 35 | Umbilical endometriosis | Spontaneous and cyclic bleeing | Goserelin acetate, and then surgical excision |

| Victory et al.6 | 47 | 46 | Umbilical bleeding | Surgical excision | |

| Boesgaard-Kjer et al.21 | 28.5 (mean age of 10 patients) | - | Periodic color change and tenderness | Surgical excision | |

| Wiegratz et al.22 | 27 | 25 | Umbilical endometriosis | Increasing cyclic pain | Oral contraceptive, and then surgical excision |

| Taniguchi et al.23 | 45 | 42 | Umbilical endometriosis | Painful umbilical mass | Surgical excision |

| Chew et al.24 | 44 | 44 | Umbilical endometriosis | Progressively enlarging umbilical nodule | GnRH analogue leuprorelin acetate |

| Claas-Quax et al.25 | 27 | 27 | Catamenial bleeding | Surgical excision | |

| Sidani et al.26 | 37 | 37 | Cyclic swelling and discharge | Surgical excision | |

| Sengupta et al.27 | 29 | 28 | Painful nodule | Excisional biopsy | |

| Minaidou et al.1 | 26 | - | Umbilical hernia | Umbilical pain and dark purplish nodule | Surgical excision |

| Weng and Yang5 | 37 | - | Cyclic bleeding | Gestrinone, and then surgical excision | |

| Kim et al.28 | 42 | 42 | Epidermal cyst | Size increase and pain | Excisional biopsy |

| Song et al.29 | 25 | 23 | Dermatofibroma | Size increase, pain, discoloration | Surgical excision |

| Kyamidis et al.30 | 37 | 27 | Umbilical endometriosis | Tenderness and occasional bleeding | Not described |

Differential diagnosis of umbilical endometriosis includes keloid, metastasis of visceral carcinoma, which is referred as Sister Mary Joseph nodule and melanoma3. Therefore, physicians should work on imaging studies such as ultrasonography or CT or magnetic resonance imaging. Furthermore, diagnosis must be confirmed histopathologically to exclude malignancy. More importantly, keloid is clinically very similar to umbilical endometriosis. Clinicians should pay particular attention to patients, especially history of surgery or trauma, and presenting symptoms that are related to menstrual cycle. If treatment with steroid intralesional injection does not improve the symptom, umbilical endometriosis should be considered for differential diagnosis.

Surgical excision is the definitive treatment. Hormonal therapy with gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonists, oral contraceptive and danazol can be used before surgical excision to decrease the size of the lesion and make symptom relief8,31. Recurrence rate is very rare9. In our case, the lesion was confirmed by umbilical ultrasonography and abdominal CT and histopathological finding, and removed by local surgical excision.

In conclusion, cutaneous endometriosis of umbilicus should now be recognized as a primary or metastatic presentation or iatrogenic complication of endometriosis. Patients with primary umbilical endometriosis should undergo careful history and physical examination to rule out potential malignancies. Moreover, differential diagnosis with keloid is very important. If the lesion diagnosed with keloid has cyclic symptoms with menstrual period, and does not improve with treatment, umbilical endometriosis should be suspected. Surgical excision is the treatment of choice to prevent recurrence and to reduce the risk of malignant transformation.

Footnotes

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST: The authors have nothing to disclose.

References

- 1.Minaidou E, Polymeris A, Vassiliou J, Kondi-Paphiti A, Karoutsou E, Katafygiotis P, et al. Primary umbilical endometriosis: case report and literature review. Clin Exp Obstet Gynecol. 2012;39:562–564. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yuen JS, Chow PK, Koong HN, Ho JM, Girija R. Unusual sites (thorax and umbilical hernial sac) of endometriosis. J R Coll Surg Edinb. 2001;46:313–315. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jaime TJ, Jaime TJ, Ormiga P, Leal F, Nogueira OM, Rodrigues N. Umbilical endometriosis: report of a case and its dermoscopic features. An Bras Dermatol. 2013;88:121–124. doi: 10.1590/S0365-05962013000100019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fernández-Aceñero MJ, Córdova S. Cutaneous endometriosis: review of 15 cases diagnosed at a single institution. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2011;283:1041–1044. doi: 10.1007/s00404-010-1484-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Weng CS, Yang YC. Images in clinical medicine. Villar's nodule--umbilical endometriosis. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:e45. doi: 10.1056/NEJMicm1009351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Victory R, Diamond MP, Johns DA. Villar's nodule: a case report and systematic literature review of endometriosis externa of the umbilicus. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2007;14:23–32. doi: 10.1016/j.jmig.2006.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Groothuis PG, Koks CA, de Goeij AF, Dunselman GA, Arends JW, Evers JL. Adhesion of human endometrium to the epithelial lining and extracellular matrix of amnion in vitro: an electron microscopic study. Hum Reprod. 1998;13:2275–2281. doi: 10.1093/humrep/13.8.2275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dadhwal V, Gupta B, Dasgupta C, Shende U, Deka D. Primary umbilical endometriosis: a rare entity. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2011;283(Suppl 1):119–120. doi: 10.1007/s00404-010-1809-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Theunissen CI, IJpma FF. Primary umbilical endometriosis: a cause of a painful umbilical nodule. J Surg Case Rep. 2015;2015:rjv025. doi: 10.1093/jscr/rjv025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Calagna G, Perino A, Chianetta D, Vinti D, Triolo MM, Rimi C, et al. Primary umbilical endometrioma: analyzing the pathogenesis of endometriosis from an unusual localization. Taiwan J Obstet Gynecol. 2015;54:306–312. doi: 10.1016/j.tjog.2014.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chikazawa K, Mitsushita J, Netsu S, Konno R. Surgical excision of umbilical endometriotic lesions with laparoscopic pelvic observation is the way to treat umbilical endometriosis. Asian J Endosc Surg. 2014;7:320–322. doi: 10.1111/ases.12128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pariza G, Mavrodin CI. Primary umbilical endometriosis (Villar's nodule)-case study, literature revision. Chirurgia (Bucur) 2014;109:546–549. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Paramythiotis D, Stavrou G, Panidis S, Panagiotou D, Chatzopoulos K, Papadopoulos VN, et al. Concurrent appendiceal and umbilical endometriosis: a case report and review of the literature. J Med Case Rep. 2014;8:258. doi: 10.1186/1752-1947-8-258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ghosh A, Das S. Primary umbilical endometriosis: a case report and review of literature. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2014;290:807–809. doi: 10.1007/s00404-014-3291-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gin TJ, Gin AD, Gin D, Pham A, Cahill J. Spontaneous cutaneous endometriosis of the umbilicus. Case Rep Dermatol. 2013;5:368–372. doi: 10.1159/000357493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kahlenberg LK, Laskey S. Primary umbilical endometriosis presenting as umbilical drainage in a nulliparous and surgically naive young woman. Am J Emerg Med. 2014;32:692.e1–692.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2013.12.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fancellu A, Pinna A, Manca A, Capobianco G, Porcu A. Primary umbilical endometriosis. Case report and discussion on management options. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2013;4:1145–1148. doi: 10.1016/j.ijscr.2013.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Efremidou EI, Kouklakis G, Mitrakas A, Liratzopoulos N, Polychronidis ACh. Primary umbilical endometrioma: a rare case of spontaneous abdominal wall endometriosis. Int J Gen Med. 2012;5:999–1002. doi: 10.2147/IJGM.S37302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kesici U, Yenisolak A, Kesici S, Siviloglu C. Primary cutaneous umbilical endometriosis. Med Arch. 2012;66:353–354. doi: 10.5455/medarh.2012.66.353-354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bagade PV, Guirguis MM. Menstruating from the umbilicus as a rare case of primary umbilical endometriosis: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2009;3:9326. doi: 10.1186/1752-1947-3-9326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Boesgaard-Kjer D, Boesgaard-Kjer D, Kjer JJ. Primary umbilical endometriosis (PUE) Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2017;209:44–45. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2016.05.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wiegratz I, Kissler S, Engels K, Strey C, Kaufmann M. Umbilical endometriosis in pregnancy without previous surgery. Fertil Steril. 2008;90:199.e17–199.e20. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2007.07.1303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Taniguchi F, Hirakawa E, Azuma Y, Uejima C, Ashida K, Harada T. Primary umbilical endometriosis: unusual and rare clinical presentation. Case Rep Obstet Gynecol. 2016;2016:9302376. doi: 10.1155/2016/9302376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chew KT, Norsaadah S, Suraya A, Hing EY, Ani Amelia Z, Nor Azlin MI, et al. Primary umbilical endometriosis successfully treated with dienogest. Horm Mol Biol Clin Investig. 2017;29:67–69. doi: 10.1515/hmbci-2016-0017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Claas-Quax MJ, Ooft ML, Hoogwater FJ, Veersema S. Primary umbilical endometriosis. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2015;194:260–261. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2015.08.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sidani MS, Khalil AM, Tawil AN, El-Hajj MI, Seoud MA. Primary umbilical endometriosis. Clin Exp Obstet Gynecol. 2002;29:40–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sengupta M, Naskar A, Gon S, Majumdar B. Villar's nodule. Online J Health Allied Sci. 2011;10:19. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kim SH, Park SJ, Lee DY, Lee ES. A case of cutaneous endometriosis. Korean J Dermatol. 2002;40:100–102. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Song WK, Park HJ, Kim YC, Cinn YW. A case of cutaneous endometriosis. Korean J Dermatol. 2000;38:999–1001. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kyamidis K, Lora V, Kanitakis J. Spontaneous cutaneous umbilical endometriosis: report of a new case with immunohistochemical study and literature review. Dermatol Online J. 2011;17:5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Purvis RS, Tyring SK. Cutaneous and subcutaneous endometriosis. Surgical and hormonal therapy. J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 1994;20:693–695. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.1994.tb00456.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]