Abstract

Background:

Private general practitioners in Malaysia largely operates as solo practices – prescribing and supplying medications to patients directly from their clinics, thus posing risk of medication-related problems to consumers. A pharmacy practice reform that integrates pharmacists into primary healthcare clinics can be a potential initiative to promote quality use of medication. This model of care is a novel approach in Malaysia and research in the local context is required, especially from the perspectives of pharmacists.

Objective:

To explore pharmacists’ views in integrating pharmacists into private GP clinics in Malaysia.

Methods:

A combination of purposive and snowballing sampling was used to recruit community and hospital pharmacists from urban areas in Malaysia to participate either in focus groups or semi-structured interviews. A total of 2 focus groups and 4 semi-structured interviews were conducted. Sessions were audio recorded, transcribed verbatim and thematically analysed using NVivo 10.

Results:

Four major themes were identified: (1) Limited potential to expand pharmacists’ roles, (2) Concerns about non-pharmacists dispensing medicines in private GP clinics, (3) Lack of trust from consumers and private GPs, (4) Cost implications. Participants felt that there was a limited role for pharmacists in private GP clinics. This was because the medication supply role is currently undertaken in private GP clinics without the need of pharmacists. The perceived lack of trust from consumers and private GPs towards pharmacists arises from the belief that healthcare is the GPs’ responsibility. This suggests that there is a need for increased public and GP awareness towards the capabilities of pharmacists’ in medication management. Participants were concerned about an increase in cost to private GP visits if pharmacists were to be integrated. Nevertheless, some participants perceived the integration as a means to reduce medical costs through improved quality use of medicines.

Conclusion:

Findings from the study provided a better understanding to help ascertain pharmacists’ views on their readiness and acceptance in a potential new model of practice.

Keywords: Pharmacists, Physicians, Primary Health Care, Delivery of Health Care, Integrated, Interprofessional Relations, Qualitative Research, Malaysia

INTRODUCTION

Primary healthcare services in Malaysia are mainly provided by two sectors: the public health clinics which are fully funded by the government and the fee-for-service private sector, including private general practitioner (GP) clinics and community pharmacies.1

In Malaysia, private GPs mainly operate as solo practices with little coordination with other healthcare providers.2 Furthermore, physicians are allowed to operate a small dispensary within their clinics in Malaysia. Throughout the years, private GPs in Malaysia are granted rights under the Poison Act 1952 to prescribe and supply medications directly from their clinics. Private GPs hire non-pharmacists to dispense medications, further limiting the opportunities for pharmacists to extend their professional duties.

Community pharmacists in Malaysia are often underutilised and operate under rigid condition.3 The general public usually consults the community pharmacists to purchase a particular prescription medicine or over-the-counter products.4 Patient counselling is offered free of charge as part of professional pharmacy services and dispensing fees are not incurred.

Private sector services are funded by out-of-pocket payments and increasingly through third party funds such as private health insurance schemes and corporations that arrange for healthcare funding for their employees.5 Although private sector services are paid out-of-pocket, consumers are increasingly utilising private healthcare facilities due to easier accessibility and shorter patient waiting times.6 However, information sharing between the healthcare settings is absent leading to fragmentation of care, thus increasing risk to polypharmacy and medications errors.7,8 Polypharmacy is common among the elderly and those with multiple chronic diseases as they take more medications and are more at risk of medication related problems.9 These patients would ideally benefit from a clinical review of their medication regimens by pharmacists. Pharmacists as medication experts can improve patient outcomes by optimizing drug therapy and promoting quality use of medication.10,11 A pharmacy practice reform that integrates pharmacists into primary healthcare clinics can be a potential initiative to deliver comprehensive primary healthcare services to the public. These services are not limited to only dispensing medications and may include medication review, education, academic detailing, medication reconciliation, general practice preceptor, disease focused clinics, formulary development, and system level activities such as quality prescribing activities (prescribing audits).12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19

One of the first few integrative practices studied in Malaysia was the Cardiovascular Risk Factors Intervention Strategies (CORFIS) trial.20 In the trial, hypertensive patients were recruited to either receive conventional care (only GP) or CORFIS care (allied healthcare team consisting of GP, pharmacist, dietician and nurse educator).20 In as early as six months, patients who received CORFIS care showed significantly better improvement in achieving target blood pressure (BP) and treatment adherence as compared to patients who were seen only by a GP.20 Despite the reported benefits, the study posted an important question on whether the significant improvement in BP outcomes was sustainable over a longer period of care. This warrants for follow-up investigations on facilitators and barriers of integrating pharmacists’ participation into GP clinics.

Some reported challenges to the adoption and integration of expanded pharmacists’ roles within the healthcare system were GPs’ reservation and pharmacists themselves who often lacked confidence and are averse to risks.21,22 Two studies in Malaysia reported reservations by the private GPs on key roles of pharmacists such as diagnosing minor ailments, maintain complete medication profile and drug information provider to physicians.23,24 A report of private GPs’ opinions on pharmacist integration revealed that they were concerned that collaborative practices with pharmacists may pose threat to the professional dominance and autonomy accorded to the private GPs in Malaysia.25 The attitudes, trust and understanding of GPs towards the skills and knowledge of pharmacists appear to be the greatest barrier towards integration of pharmacists into GP clinics.25 Similarly, healthcare consumers was also reported to have low expectations toward the role of pharmacists working within GP clinics, suggesting that engagement of pharmacists in health improvement activities tend to be passive and product-orientated.26 Therefore, the importance of individual pharmacist assertiveness and confidence is a key factor in overcoming many of the integration barriers.21,22 Pharmacists who possess these personality traits might be better suited to work in a multidisciplinary general practice setting.

The lack of remuneration is a commonly expressed barrier preventing pharmacists from providing more clinical care services.27,28,29 However, a systematic review by Houle et al. showed that mere presence of remuneration scheme did not ensure uptake in practice.30 For example, pharmacist participation in the remuneration programs was found to vary considerably, with some programs reporting very low numbers of participating pharmacies31,32 and others reporting a high initial expression of interest but short persistence or very low patient enrolment over time.33,34,35

Integrating pharmacists into GP clinics is a new notion in the Malaysian setting. This study aimed to provide insights on the views of pharmacists and to identify perceived facilitators and barriers of integrating pharmacists into private GP clinics. A better understanding of this area will help ascertain the readiness and acceptance of pharmacists in a potential new model of practice.

METHODS

This study received ethical clearance by the International Medical University Joint-Committee (IMU-JC) of Research and Ethics Committee (IMU R 117/2013). A Project Advisory Group (PAG) was formed consisting of representatives of key stakeholder organisations. The PAG was a committee of experts invited from Malaysia’s peak professional pharmacy and medical organisations, Ministry of Health, community pharmacy and pharmacy educators, who have agreed to share their knowledge with the researchers. The aim of the PAG was to discuss and assist the development of semi-structured interview questions and a questioning route for focus group discussions, guided by what is known in the literature as well as their expertise in the primary healthcare environment.

Qualitative research using inductive approach from perspectives, feelings and experiences of pharmacists were engaged to generate novel insights on pharmacist integration into private GP clinics.36 For this purpose, data collection methods consisting of semi-structured interviews and focus groups were chosen since little is known about the topic in the Malaysian context. Semi-structured interviews were carried out with those who were unable to commit to a focus group session due to their busy schedule. The interviews and focus groups were conducted by one researcher (PSS) utilising an interview guide (Online Appendix) to ensure rigour and consistency in the questions asked.

Sampling and recruitment

Letters of invitation were disseminated to peak national professional pharmacy organisation and managers of ten community pharmacies to identify potential participants. Community pharmacists and private hospital pharmacists were engaged as participants as they would best represent the position of the pharmacist working within the private primary healthcare setting in this research. Recruitment was also done though snowballing technique as participants suggested potential candidates (if possible) within their social networks and expertise to participate in the study. The sample size was determined by data saturation and interviews were stopped when no new themes emerged from the interviews.

Interview Guide and Validity

A guide was used to conduct the interviews and focus groups. The guide was tested with a community pharmacist for face validation. Key topics in the guide included potential roles of integrated pharmacist, barriers and facilitators to integration, the benefits to integration and pharmacists’ remuneration. Probing questions and examples of potential scenarios were provided where necessary to encourage participant engagement. To reduce interviewer bias, the probing questions common to all the focus groups and semi-structured interviews were used to facilitate discussion.

Data collection

Data was collected between September and October 2013. Written consent was obtained from all participants. Anonymous demographic data was collected from the participants through a short questionnaire prior to the start of each focus group and semi-structured interview. The interviews and focus groups were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim.

Interviews and focus groups were carried out at a mutually agreed place and facilitated by PSS. Field notes identifying the main points gleaned from the discussion were taken throughout the focus group and interview sessions. The semi-structured interviews, focus group discussion and field notes served to triangulate the data. All participants were offered a copy of their interview transcript for content verification.

Data analysis

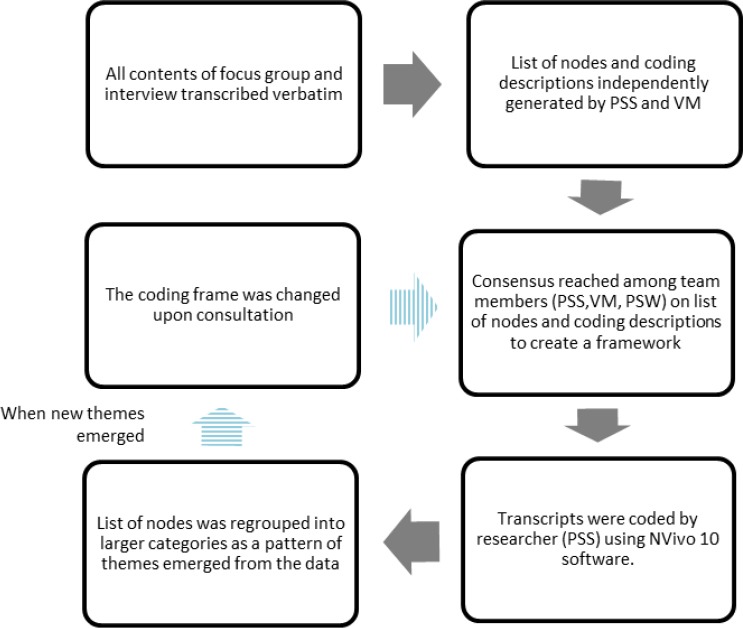

Data was analysed using a general inductive approach to derive findings in the context of focused evaluation questions (Figure 1).37 Transcripts were read several times by two researchers (PSS, VM) to independently create a list of nodes and coding descriptions. An agreed framework of nodes was generated from a consensus among team members (PSS, VM, PSW). The researcher (PSS) coded all the transcripts based on the agreed framework of nodes using the NVivo 10 software (QSR, Melbourne). The nodes were regrouped into larger categories as a pattern of themes emerged from the data. Emerging themes were developed by studying the transcripts repeatedly and considering possible meanings and how these fitted with developing themes. Themes generated were then checked with the original transcripts to make sure they were grounded in the data.

Figure 1. General inductive approach.

During the interpretation stage, researchers reviewed beyond descriptions of individual transcripts towards developing themes which offered possible explanations for what was happening within the data. This process was influenced both by the original research objectives and by new concepts generated inductively (participants’ experiences and views) from the data. Each theme was supported by verbatim quotations from participants that would best represent the idea of the theme. Towards the end of the study when no new theme emerged, this suggested that major themes had been identified. This is known as data saturation. Regular team meetings among the researchers (PSS, VM and PSW) facilitated critical exploration of participant responses, discussion of deviant cases and agreement on recurring themes.

RESULTS

A total of 19 pharmacists participated in two focus groups and four semi-structured interviews. The focus groups ran for approximately one hour and semi-structured interviews each lasted 30 minutes on average. Mean age (SD) of the participants was 29.7 (SD=4.7) years, with a range of 25 to 41 years. Demographic characteristics of participants are listed in Table 1.

Table 1. Demographic characteristics of participants. (n=19).

| Characteristics | Participants |

|---|---|

| Interview method | |

| Focus Group 1 | 7 |

| Focus Group 2 | 8 |

| Semi-structured interviews | 4 |

| Years of practice | |

| Less than 5 years | 12 |

| 5 to 10 years | 4 |

| 10 to 15 years | 2 |

| More than 15 years | 1 |

| Area of practice | |

| Community pharmacy | 17 |

| Private hospital | 2 |

Four major themes emerged from the focus groups and semi-structured interviews and are supported by illustrative quotations from the participants (P = Pharmacist). A summary of themes and illustrative quotations is illustrated in Table 2.

Table 2. Themes and illustrative quotations.

| Themes | Illustrative quotations |

|---|---|

| Pharmacists envisioning their main role as dispensing medications | P3: So again it’s quite dangerous in the sense that you tend to question or query about the safety of the medication because these technicians, they are basically not trained. So they will just follow whatever the doctor has written or ask them to do. P6: We, pharmacist (will) give out the medication instead of the nurses. P11: The pharmacist will be assigned to dispense medication and at the same time provide some advice or information to doctors. P2: I think that will a good thing because if there is any mistake or anything that the doctors do, pharmacists will be able to pick up so they sort of counter check on each other. |

| Difficulty envisioning roles beyond medication supply (i) Limited roles for pharmacist in private GP clinics (ii) Perceived roles similar to pharmacists in public hospitals or clinics |

P11: So pharmacist will be assigned to be the person in charge for dispensing medication. And the same time can provide some advice or some information to doctors. P2: I’m not too sure what other services they (pharmacists) do (in a private clinic). Or perhaps I have not given much thought to it. P11: Maybe you can have some pilot study… see how is the outcome (about integrating pharmacist into clinic). P10: First thing is dispensing separation has to be done first la. Without this, we cannot do any further la. Like change dose, prescribe medication, all of this is beyond our scope. Now the limiting factor is the dispensing separation. P1: By seeing the common illnesses, I (as the GPs) can earn money also so why do I need to put a pharmacist in my store (clinic) just too maybe see what I’m doing. P1: People (will) know what pharmacists do instead of just dispensing (medication)… A lot of people don’t understand actually the role of pharmacist. So this will bring up the value of the pharmacist in Malaysia. P9: Like (in) klinik kesihatan, pharmacist actually do more than the dispensing role… the pharmacist makes an appointment with the patient, have a small group discussion or finding out the (medication-related) problem with the patient before referring to the GP. |

| Lack of support and recognition by consumers and private GPs (i) Poor working relationship with private GPs (ii) Lack of recognition from consumers |

P4: Doctors are protecting their prescribing rights, pharmacist want their dispensing rights. Both are fighting for their own rights so it’s difficult to work closely for the time being because of the dispensing issue. P12: These days, pharmacist and GP are like enemies. We don’t communicate. P2: (The challenge would be) getting the doctors to work with pharmacist. P18: The major problem is the doctors view it as pharmacists trying to share a piece of their cake. P5: In order for this (pharmacist integration) to work, they (GPs and pharmacists) need to be able to work together. P14: For some people they don’t believe in pharmacist because they think that doctor is more superior, more competent. So we have to change the perception of the public. P9: Traditionally, Malaysian patients look up to doctors like God. So whatever the doctors say they will listen. So maybe we (pharmacists) are quite difficult to come in. |

| Cost implications from integrating pharmacists into private GP clinics | P18: I think from the doctor point of view is the cost. Because you may not want to hire someone, another 6 to 7k just to dispense medication. P10: The objective is good but it’s not practical… Even the doctors are cutting budget for their locums. P9: It’s something to think about because at the end of the day, the cost will be passed on to the consumers. So if you are going to adopt this idea, it’s (medical bills) going to escalate even more. P10: The service charge, consultation also will be increased. They have to pay the consultation fees to doctor as well as the consultation fees for pharmacist. P13: I think if you (pharmacists) play your role well, I think yes (for consumers to pay). Why not? P9; Depends on what service (provided by pharmacist). P5: No, because in the first place they are already asking for cheaper prices for medications, what makes you think they will actually pay extra 5 ringgit for consultation. P2: If it’s out of their own pocket, no. I don’t think there’s such thing as pharmacist consultation fee or anything like that. P5: I suppose private clinics could actually get some sort subsidy from the government. |

(Note: ‘la’ is a suffix of no standard meaning used in the Malaysian colloquial)

Theme 1: Pharmacists envisioned their main role as dispensing medications.

All participants brought up the issue of non-pharmacy trained clinic staff dispensing medications to their patients. Some participants referred to the clinic staff as ‘nurses’, ‘assistants’, ‘high school graduates’ and ‘technicians’. With the current state of practice, the participants were concerned about patient and medication safety in clinics since these clinic staff were largely not formally trained to supply medications. The participants strongly felt that the role of dispensing of medications should be best left to pharmacists. In addition, some participants added that the pharmacist can provide advice and medication information to the GPs when required. Most participants commented that the pharmacist working in the private GP clinic will be able to provide a check-and-balance mechanism before medications are dispensed to consumers. One of the participants stressed that prescribing and counter-checking of medications should not be carried out by the same person, i.e. GPs.

Theme 2: Difficulty envisioning roles beyond medication supply

(i) Limited roles for pharmacist in private GP clinics

Most participants expressed that the potential pharmacist activities in private GP clinics include dispensing medication to consumers and providing medication information to private GPs. When enquired on other potential pharmacy services besides dispensing medications, most participants were unable to answer. They have not seen or experienced pharmacists working in private GP clinics before, therefore have not thought about it. Some participants also suggested to trial pharmacist working in private GP clinics to help visualise some of the potential roles.

Dispensing separation was heavily discussed among all participants. The participants strongly insisted that currently without dispensing rights for pharmacists, it would be difficult to develop new pharmacist roles within the private GP clinics. The participants perceived that the GPs may also feel the redundancy of pharmacists’ roles in the clinic as GPs can treat common illnesses without the presence of pharmacists. Though majority of the participants were unable to envision the potential roles for pharmacists in private GP clinics, one-third of the participants saw the opportunity for pharmacists to be integrated into general practice as a way to help improve awareness and societal value of pharmacists within the Malaysian community.

(ii) Perceived roles similar to pharmacists in public hospitals/clinics

Upon prompting, participants envisaged the pharmacist’s role in private GP clinics to be similar to the current roles of pharmacists in public hospitals or public clinics (known locally as the ‘klinik kesihatan’). The medication therapy adherence clinic (MTAC) led by pharmacists in the public sector, was mentioned as an example among the participants. In these pharmacist-led clinic sessions, the pharmacist reviews the patient’s medications and discuss of any medication-related problems before referring them to see the GP.

Theme 3: Lack of support and recognition by consumers and private GPs

(i) Poor working relationship with private GPs

All participants revealed that GPs and pharmacists do not work collaboratively. One participant termed the current relationship between pharmacists and GPs as “like enemies”. According to the participants, the poor working relationship between private GPs and pharmacists stem from the lack of dispensing separation and poor communication between the two professions. All participants also agreed that GPs’ acceptance and their willingness to work with the pharmacist in private GP clinics pose as a challenge to integration. Some participants indicated that private GPs were mostly concerned about pharmacists to taking over their roles and revenue/business. Overall, the participants felt that the working relationship between GPs and pharmacists needs to be improved before pharmacist integration into private GP clinic can take place.

(ii) Lack of recognition from consumers

A number of participants felt that the public often regarded doctors as a superior figure compared with pharmacists. The participants felt such public perception hinders the potential role for pharmacists.

Theme 4: Cost implications from integrating pharmacists into private GP clinics

The majority of participants agreed on a funding model where the consumers will pay for a pharmacist service in private GP clinics. Other potential funding options include joint venture between pharmacists and private GPs, and for pharmacists’ fee to be incorporated into dispensed medications. On whether the integrated pharmacists should be paid by private GPs in the form of salary, most participants doubted if private GPs would pay a monthly salary of MYR 6,000 (approximately USD 1,700) for pharmacists to supply medications in the clinic.

Even though most participants suggested a consumer funded model, they had concerns about consumers bearing the extra costs for the pharmacists’ service. The participants had mixed responses as to whether the consumers would be willing to pay for the pharmacist services. Some participants were confident that consumers would be willing to pay while some others felt that it depended on the type of service provided. However, the majority felt that consumers would not be willing to pay extra to pharmacists since dispensing and counselling services are currently provided free of charge. They cited incidences where consumers were already haggling for cheaper medications, thus making them question as to whether consumers would actually be willing to pay extra for pharmacists’ consultation if the new model were to come into practice. This opposes to the doctor’s consultation fees which are currently included in the treatment fee (including procedures and medications) as a lump sum, which consumers do not regard as an additional payment. A number of participants suggested for the government to provide financial support in the form of a subsidy to facilitate pharmacists’ integration into private GP clinic.

DISCUSSION

This study found that pharmacist participants felt that their main role in private GP clinics would be medication supply and had difficulty envisioning roles beyond that. The strong adherence to the traditional role of dispensing resonates with the article by Rosenthal et al. where the authors suggested that pharmacists have personality traits of paralysis in the face of ambiguity.22 The authors hypothesised that the biggest barrier to practice change is an existing underlying pharmacy culture that is resistant to change.22 This is in contrast to early career participants in this study, who were hungry for change and keenly interested in acting on that desire to expand their roles in the primary care. In literature, “early adopters” of practice innovations were typically described as being younger, more often seen as opinion leaders and more educated than their peers.38 Future implementation research should be directed in engaging these early adopters and their needs studied more closely, to facilitate successful pharmacy practice change.

The opportunities and challenges discussed in the study reflected the needs for pharmacy training and education to keep pace with the expanding roles of pharmacists. Pharmacy students in Malaysia are trained in providing pharmaceutical care, but most of the time, pharmacy practice is concentrated on technical and retailing activities which may not allow the full use of their knowledge and skills.39 A Malaysian study on pharmacy student activities during clinical placements found that the common activities were related to supply of medications and packing of drugs.40 The mismatch between their training and current practice may not give them the opportunity to assume professional responsibility in patient care roles. The difficulty in envisioning roles beyond medication supply may also be due to the lack of exposure to be flexible in evolving models of practice and the fear of new responsibility.22 The schools of pharmacy therefore hold the responsibilities to equip the profession with the competency in terms of knowledge and skills to practice. Unless pharmacy graduates have been inculcated with this mind-set during their education, they may be reluctant to perform tasks beyond supply of medications.

Lack of public’s trust towards pharmacists and absence of dispensing separation were expressed by participants as barriers to extend their roles into private GP clinics. Similarly, reports of lack of understanding in pharmacists’ roles by the community have also been shared in the international literature.41,42,43 In Taiwan, nearly 80% of consumers agreed that the only responsibility of a pharmacist was to accurately dispense medications as prescribed.33 The reason could be due to traditional belief that healthcare is solely the GPs’ responsibility as private GPs prescribe and supply medications at their clinics.

Additionally most participants envisage pharmacists’ roles in private GP clinics would resemble those of which are observed in the public healthcare setting. Value-added services such as Medication Therapy Adherence Clinic (MTAC) involving medication management and disease monitoring are pharmacist-led activities provided in the public hospitals and clinics. These pharmacists work in close collaboration with their physicians to provide the best pharmaceutical care for the patients. Therefore, participants deemed activities similar to MTAC were suitable to be provided by an integrated pharmacist who would closely work in collaboration with the private GP in the clinic instead of independent pharmacy consultations by a community pharmacist. This was because Malaysian community pharmacists often reported lack of time, large workload and inadequate drug information sources as limitations in the provision of these services.45,46

On separate studies, the Malaysian private GPs and consumers perceived integrated pharmacists to be helpful in roles beyond dispensing medication, including prescribing audits, medication review, drug information, education on therapeutic management of disease, patient advocacy and medication stock management.25,26 While integration provides greater opportunity for communication between pharmacist and GP, there remained concerns that pharmacists may remove parts of the GPs’ function and jeopardise the clinic’s business.25 In this study, working relationship between private GPs and pharmacists were found to be both a key barrier and facilitator to integrating a pharmacist into private GP clinics. This finding was similar to studies conducted by Freeman et al. and Tan et al.27,29 Antagonism between both professions is best explained by the long standing conflict between dispensing doctors and pharmacists, who are potentially in competition for business.47 The struggle over ‘turf wars’ between doctors and pharmacists is nothing new in the implementation of clinical services in primary care.48,49,50 What often gets lost in these ‘turf wars’ is the consumers. Thus, healthcare consumers have highlighted the need of greater collaboration between GPs and pharmacists, and if barriers exist, these must be overcome before comprehensive inter-professional relationship can be realised.26 For pharmacist collaboration with GPs to be successful, there must also be a willingness from both parties to work together. The placement of highly trained pharmacists within GP clinics or ‘co-location’ can be considered for this purpose. Co-location of pharmacists and private GPs could increase rapport, professional trust and communication between the two professions.51 Additionally, early working relationship may also be nurtured during their undergraduate years through inter-professional education.52 By creating opportunities for early exposure and interaction, GPs and pharmacists can recognise and appreciate each other’s roles, thus building confidence and encouraging teamwork.

Cost was also discussed heavily in this study. Most participants immediately identified pharmacist integration to an increased cost to private GPs which will consequently burden consumers. However, some participants saw this novel model as a means to reduce hospitalisations and cost through better quality use of medication. This finding was similar to that by Ramalho et al. and Isetts et al. which reported cost savings attributable to the integration of a pharmacist to a primary healthcare practice.31,53 In this study, although most participants felt that consumers would not be willing to pay extra for pharmacy services, a separate study on consumers’ willingness to pay for a pharmacy-based bone mineral density (BMD) testing in Malaysia showed otherwise. Eleven out of 17 participants would go to a pharmacy for BMD testing and be willing to pay the pharmacist between MYR 0 to MYR 50 (approximately USD 12).54 It is also important to understand that for-profit, private sector providers will usually supply services for which individuals are willing to pay. They will tend not to provide services for which little demand exists. Decision-makers who wish to increase the coverage of effective public health interventions where members of the community do not see them as necessary or even desirable, face a particular challenge. Therefore, they need to stimulate demand. Where there is demand, and therefore willingness to pay, private sector healthcare providers will be more inclined to provide these services; although government supports and subsidies may still be necessary to raise coverage to the desired level.55

When considering the study as a whole, the interpretation of the results may be limited by two main factors. Firstly, the project recruited participants who were mainly within the Klang Valley and highly urbanised areas. Although qualitative research, by its nature, served to provide insight into issues and experiences of participants, the number of participants recruited is often small. Also, the participants were not recruited using a random selection procedure. For these reasons, the results obtained may not be regarded as being representative of the Malaysian population as a whole. Nevertheless, findings from this study provided a better understanding to help ascertain the readiness and acceptance of pharmacists in a potential new model of practice. These results can be triangulated with local published data on perspectives from other stakeholders, giving a broader idea to the practice model. Future research should focus on achieving generalisation through a large-scale questionnaire and a retrospective review of pre- and post-integration study while providing guiding principles on successful integration. Outcomes describing characteristics of the pharmacist and primary healthcare setting, and how the pharmacist interacts within this setting could be investigated.

CONCLUSIONS

This study highlighted the perceived roles of pharmacists, barriers and facilitators of integrating pharmacists into private GP clinics. These findings have high strategic relevance to current directions of the pharmacy profession. Given the growing demand for healthcare services in our ageing population, this study has the potential to guide the pharmacy profession and pharmacists, towards accepting their responsibility within the healthcare system in the area of patient care.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The authors would like to thank all participants for their contribution to this study.

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

No conflicts of interest have been declared.

FUNDING

This work was supported by the Exploratory Research Grant Scheme (ERGS) from the Ministry of Education (MOE) Malaysia [grant number ERGS/1/2013/SKK02/ IMU/03/2].

Contributor Information

Pui S. Saw, School of Pharmacy, Monash University Malaysia. Selangor (Malaysia). saw.pui.san@monash.edu

Lisa Nissen, Professor and Head, School of Clinical Sciences, Queensland University of Technology, Brisbane QLD (Australia). l.nissen@qut.edu.au.

Christopher Freeman, Clinical Senior Lecturer in QUM, School of Pharmacy, University of Queensland. St Lucia, QLD (Australia). c.freeman4@uq.edu.au.

Pei S. Wong, Senior lecturer, School of Pharmacy, International Medical University. Kuala Lumpur (Malaysia). peise_wong@imu.edu.my

Vivienne Mak, Lecturer, Faculty of Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Sciences, Monash University. Parkville (Australia). vivienne.mak@monash.edu.

References

- 1.Jaafar S, Mohd Noh K, Abdul Muttalib K, Othman N, Healy J. Malaysia Health System Review. Health Systems in Transition. 2013;3(1):1–103. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ramli A, Taher S. Managing chronic diseases in the Malaysian primary health care –a need for change. Malays Fam Physician. 2008;3(1):7–13. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wong SS. Pharmacy practice in Malaysia. Malaysian Journal of Pharmacy. 2001;1(1):2–8. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chua SS, Lim KP, Lee HG. Utilisation of community pharmacists by the general public in Malaysia. Int J Pharm Pract. 2013;21(1):66–69. doi: 10.1111/j.2042-7174.2012.00219.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chee HL. Ownership, control, and contention:challenges for the future of healthcare in Malaysia. Soc Sci Med. 2008;66(10):2145–2156. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.01.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Aljunid S. The role of private medical practitioners and their interactions with public health services in Asian countries. Health Policy Plan. 1995;10(4):333–349. doi: 10.1093/heapol/10.4.333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ministry of Health Malaysia. [accesed 29 December 2014];Country Health Plan:10th Malaysia Plan. 2011-2015 Available at: http://www.moh.gov.my/images/gallery/Report/Country_health.pdf .

- 8.Fialová D, Onder G. Medication errors in elderly people:contributing factors and future perspectives. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2009;67(6):641–645. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2009.03419.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Junius-Walker U, Theile G, Hummers-Pradier E. Prevalence and predictors of polypharmacy among older primary care patients in Germany. Fam Pract. 2007;24(1):14–19. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cml067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Freeman CR, Cottrell WN, Kyle G, Williams ID, Nissen L. An evaluation of medication review reports across different settings. Int J Clin Pharm. 2013;35(1):5–13. doi: 10.1007/s11096-012-9701-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chua SS, Kok LC, Md Yusof FA, Tang GH, Lee SWH, Efendie B, Paraidathathu T. Pharmaceutical care issues identified by pharmacists in patients with diabetes, hypertension or hyperlipidaemia in primary care settings. BMC Health Serv Res. 2012;12:388. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-12-388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dolovich L, Pottie K, Kaczorowski J, Farrell B, Austin Z, Rodriguez C, Gaebel K, Sellors C. Integrating family medicine and pharmacy to advance primary care therapeutics. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2008;83(6):913–917. doi: 10.1038/clpt.2008.29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fish A, Watson MC, Bond CM. Practice-based pharmaceutical services:a systematic review. Int J Pharm Pract. 2002;10(4):225–233. doi: 10.1211/096176702776868451. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ables AZ, Baughman OL., 3rd The clinical pharmacist as a preceptor in a family practice residency training program. Fam Med. 2002;34(9):658–662. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cone SM, Brown MC, Stambaugh RL. Characteristics of ambulatory care clinics and pharmacists in Veterans Affairs medical centers:an update. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2008;65(7):631–635. doi: 10.2146/ajhp070198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Martin RM, Lunec SG, Rink E. UK postal survey of pharmacists working with general practices on prescribing issues:characteristics, roles and working arrangements. Int J Pharm Pract. 1998;6(3):133–139. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Carter BL, Malone DC, Billups SJ, Valuck RJ, Barnette DJ, Sintek CD, Ellis S, Covey D, Mason B, Jue S, Carmichael J, Guthrie K, Dombrowski R, Geraets DR, Amato M. Impact of Managed Pharmaceutical care on resource utilization and Outcomes in Veterans affairs medical centers. Interpreting the findings of the IMPROVE study. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2001;58(14):1330–1337. doi: 10.1093/ajhp/58.14.1330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lowe CJ, Raynor DK, Purvis J, Farrin A, Hudson J. Effects of a medicine review and education programme for older people in general practice. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2000;50(2):172–175. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2125.2000.00247.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Farrell B, Ward N, Dore N, Russell G, Geneau R, Evans S. Working in interprofessional primary health care teams:What do pharmacists do? Res Social Adm Pharm. 2013;9(3):288–301. doi: 10.1016/j.sapharm.2012.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Low WH, Seet W, Ramli AS, Ng KK, Jamaiyah H, Dan SP, Teng CL, Lee VK, Chua SS, Md Yusof FA, Karupaiah T, Chee WS, Goh PP, Zaki M, Lim TO. Community-based cardiovascular Risk Factors Intervention Strategies (CORFIS) in managing hypertension:A pragmatic non-randomised controlled trial. Med J Malaysia. 2013;68(2):129–135. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Frankel GE, Austin Z. Responsibility and confidence:identifying barriers to advanced pharmacy practice. Can Pharm J (Ott) 2013;146(3):155–161. doi: 10.1177/1715163513487309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rosenthal M, Austin Z, Tsuyuki RT. Are pharmacists the ultimate barrier to pharmacy practice change? Can Pharm J (Ott) 2010;143:37–42. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hassali M, Awaisu A, Shafie A. Professional Training and Roles of Community Pharmacists in Malaysia:Views from General Medical Practitioners. Malays Fam Physician. 2009;4(2-3):71–76. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sarriff A, Nordin N, Hassali MA. Extending the Roles of Community Pharmacists:Views from General Medical Practitioners. Med J Malaysia. 2012;67(6):577–581. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Saw PS, Nissen L, Freeman C, Wong PS, Mak V. A new role of pharmacists in private primary healthcare clinics in Malaysia:the views of general practitioners. J Pharm Pract Res. 2017;47(1):27–33. doi: 10.18549/PharmPract.2017.03.971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Saw PS, Nissen LM, Freeman C, Wong PS, Mak V. Health care consumers' perspectives on pharmacist integration into private general practitioner clinics in Malaysia:a qualitative study. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2015;9:467–477. doi: 10.2147/PPA.S73953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Freeman C, Cottrell WN, Kyle G, Williams I, Nissen L. Integrating a pharmacist into the general practice environment:opinions of pharmacist's, general practitioner's, health care consumer's, and practice manager's. BMC Health Serv Res. 2012;12:229. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-12-229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jorgenson D, Laubscher T, Lyons B, Palmer R. Integrating pharmacists into primary care teams:barriers and facilitators. Int J Pharm Pract. 2014;22(4):292–299. doi: 10.1111/ijpp.12080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tan EC, Stewart K, Elliott RA, George J. Integration of pharmacists into general practice clinics in Australia:the views of general practitioners and pharmacists. Int J Pharm Pract. 2014;22(1):28–37. doi: 10.1111/ijpp.12047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Houle SK, Grindrod KA, Chatterley T, Tsuyuki RT. Paying pharmacists for patient care:A systematic review of remunerated pharmacy clinical care services. Can Pharm J (Ott) 2014;147(4):209–232. doi: 10.1177/1715163514536678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Isetts BJ, Schondelmeyer SW, Artz MB, Lenarz LA, Heaton AH, Wadd WB, Brown LM, Cipolle RJ. Clinical and economic outcomes of medication therapy management services:the Minnesota experience. J Am Pharm Assoc (2003) 2008 Mar-Apr;48(2):203–211. doi: 10.1331/JAPhA.2008.07108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Thompson CA. State-paid medication therapy management services succeed. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2008;65(6):490–498. doi: 10.2146/news080022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lee E, Braund R, Tordoff J. Examining the first year of Medicines Use Review services provided by pharmacists in New Zealand. N Z Med J. 2008;2009;122(1293):3566. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jackson M, Gaspic-Piskovic M, Cimino S. Description of a Canadian employer-sponsored smoking cessation program utilizing community pharmacy-based cognitive services. Can Pharm J (Ott) 2008;141(4):234–240. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Look KA, Mott DA, Leedham RK, Kreling DH, Hermansen-Kobulnicky CJ. Pharmacy participation and claim characteristics in the Wisconsin Medicaid Pharmaceutical Care Program from 1996 to 2007. J Manag Care Pharm. 2012 Mar;18(2):116–128. doi: 10.18553/jmcp.2012.18.2.116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pope C, Mays N. Reaching the parts other methods cannot reach:an introduction to qualitative methods in health and health services research. BMJ. 1995;311(6996):42–45. doi: 10.1136/bmj.311.6996.42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Thomas D. A General Inductive Approach for Analyzing Qualitative Evaluation Data. Am J Eval. 2006;27(2):237–246. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jorgenson D, Gubbels-Smith A, Farrell B, Ward N, Dolovich L, Jennings B. Characteristics of pharmacists who enrolled in the pilot ADAPT Education Program:Implications for practice change. Can Pharm J (Ott) 2012;145(6):260–263. doi: 10.3821/145.6.cpj260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hassali MA, Shafie AA, Awaisu A, Mohamed Ibrahim MI, Ahmed SI. A public health pharmacy course at a Malaysian pharmacy school. Am J Pharm Educ. 2009;73(7):136. doi: 10.5688/aj7307136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ting KN, Wong KT, Thang SM. Contributions of Early Work-Based Learning:A Case Study of First Year Pharmacy Students. International Journal of Teaching and Learning in Higher Education. 2009;22(3):326–335. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Olsson E, Tuyet LT, Nguyen HA, Stalsby Lundborg C. Health professionals' and consumers' views on the role of the pharmacy personnel and the pharmacy service in Hanoi, Vietnam:a qualitative study. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2002;27(4):273–280. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2710.2002.00421.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kamei M, Teshima K, Fukushima N, Nakamura T. Investigation of patients'demand for community pharmacies:relationship between pharmacy services and patient satisfaction. Yakugaku Zasshi. 2001;121(3):215–220. doi: 10.1248/yakushi.121.215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kamat VR, Nichter M. Pharmacies, self-medication and pharmaceutical marketing in Bombay, India. Soc Sci Med. 1998;47(6):779–794. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(98)00134-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wen MF, Lin SJ, Yang YH, Huang YM, Wang HP, Chen CS, Wu FL. Effects of a national medication education program in Taiwan to change the public's perceptions of the roles and functions of pharmacists. Patient Educ Couns. 2007;65(3):303–310. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2006.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sarriff A. A survey of patient-oriented services in community pharmacy practice in Malaysia. J Clin Pharm Ther. 1994;19(1):57–60. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2710.1994.tb00810.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hassali MA, Subish P, Shafie AA, Ibrahim MIM. Perceptions and Barriers towards Provision of Health Promotion Activities among Community Pharmacists in the State of Penang, Malaysia. J Clin Diagn Res. 2009;3(3):1562–1568. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Amzan K. Pharmacists vs doctors:The ongoing ‘debate'. [accessed 17 June 2015];The Malay Mail Online 2015. Available at: http://www.themalaymailonline.com/opinion/kamal-amzan/article/pharmacists-vs-doctors-the-ongoing-debate .

- 48.McDonough RP, Rovers JP, Currie JD, Hagel H, Vallandinghanl J, Sobotka J. Obstacles to the implementation of pharmaceutical care in the community setting. J Am Pharm Assoc. 1998;38(1):87–95. doi: 10.1016/S1086-5802(16)30296-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kucukarslan S, Lai S, Dong Y, Al-Bassam N, Kim K. Physician beliefs and attitudes toward collaboration with community pharmacists. Res Social Adm Pharm. 2011;7(3):224–232. doi: 10.1016/j.sapharm.2010.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hughes CM, McCann S. Perceived interprofessional barriers between community pharmacists and general practitioners:a qualitative assessment. Br J Gen Pract. 2003;53(493):600–606. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bradley F, Elvey R, Ashcroft DM, Hassell K, Kendall J, Sibbald B, Noyce P. The challenge of integrating community pharmacists into the primary health care team:a case study of local pharmaceutical services (LPS) pilots and interprofessional collaboration. J Interprof Care. 2008;22(4):387–398. doi: 10.1080/13561820802137005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Van C, Costa D, Abbott P, Mitchell B, Krass I. Community pharmacist attitudes towards collaboration with general practitioners:development and validation of a measure and a model. BMC Health Serv Res. 2012;12:320. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-12-320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ramalho de Oliveira D, Brummel AR, Miller DB. Medication therapy management:10 years of experience in a large integrated health care system. J Manag Care Pharm. 2010;16(3):185–195. doi: 10.18553/jmcp.2010.16.3.185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Jacob S, Sarriff A. An explorative study of pharmacy-based bone mineral density testing. Malaysian J Pharm Sci. 2006;4(2):1–14. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Swan M, Zwi A. Private practitioners and public health:close the gap or increase the distance. Department of Public Health and Policy, London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine. 1997 [Google Scholar]