Abstract

The distribution range of the western pine beetle Dendroctonus brevicomis LeConte (Coleoptera: Curculionidae) is supported only by scattered records in the northern parts of Mexico, suggesting that its populations may be marginal and rare in this region. In this study, we review the geographical distribution of D. brevicomis in northern Mexico and perform a geometric morphometric analysis of seminal rod shape to evaluate its reliability for identifying this species with respect to other members of the Dendroctonus frontalis Zimmermann (Coleoptera: Curculionidae) complex. Our results provide 30 new records, with 26 distributed in the Sierra Madre Occidental and 4 in the Sierra Madre Oriental. These records extend the known distribution range of D. brevicomis to Durango and Tamaulipas states in northern Mexico. Furthermore, we find high geographic variation in size and shape of the seminal rod, with conspicous differences among individuals from different geographical regions, namely west and east of the Great Basin and between mountain systems in Mexico.

Keywords: seminal rod shape, geometric morphometry, Dendroctonus frontalis complex

The western pine beetle (WPB) Dendroctonus brevicomis LeConte (Coleoptera: Curculionidae) is a bark beetle well known in Canada and the United States. It is an aggressive species capable of killing large numbers of pine trees during outbreaks (Miller and Keen 1960, Bright 1976, Six and Bracewell 2015). The WPB occurs across the west coast in southern British Columbia in Canada as far south as southern California, and from Idaho and eastern Montana to central Arizona and western Texas (Wood 1982). This range coincides with those of its principal hosts, Pinus ponderosa Douglas ex C. Lawson (Pinales: Pinaceae) and P. coulteri D. Don (Pinales: Pinaceae), which form pine forests at elevations between 300 and 1800 m (Miller and Keen 1960, Wood 1963, DeMars and Roettgering 1982, Strom et al. 2001, Six and Bracewell 2015).

The first record of this bark beetle species in Mexico was reported by Swaine (1918) as Dendroctonus barberi Hopkins, a synonym of D. brevicomis, in the northern region of the country. Since then, few studies have recorded its presence in this region. For example, Wood (1963, 1982) documented this species from Tres Rios in Chihuahua state; Perusquía (1978) displayed the seminal rod of one specimen from Arroyo de los Novillos, Mesa del Huracán in the same state; Lanier et al. (1988) described the seminal rod of specimens collected in Puerto del Tarillo, 10 km south of Galeana, Nuevo Leon; and Sánchez-Martínez et al. (2007) collected specimens in funnel traps in Sierra de Arteaga, Coahuila. Other studies have suggested that D. brevicomis could also be present in Coahuila, Durango, and Zacatecas states (Atkinson 2017, Cibrián-Tovar et al. 1995). However, due to the lack of vouchers in entomological collections and reliable data in the literature, subsequent studies on the distribution range of the Dendroctonus species in Mexico considered only 10 valid records for D. brevicomis in Chihuahua, Durango, and Nuevo Leon states (Salinas-Moreno et al. 2004, 2010). All this information suggests that the populations of this species may be marginal and rare in Mexico.

However, recent studies carried out in Dendroctonus frontalis Zimmermann (Coleoptera: Curculionidae) complex species, such as D. frontalis,Dendroctonus mesoamericanus Armendáriz-Toledano and Sullivan (Curculionidae: Scolytinae), Dendroctonus mexicanus Hopkins (Coleoptera: Scolytidae) and Dendroctonus vitei Wood (Coleoptera: Curculionidae: Scolytinae) (Armendáriz-Toledano et al. 2014a,b), have demostrated that the taxonomic identification of species from this complex in Mexico and Central America is difficult and problematic because the wide morphological variation of their body attributes (Armendáriz-Toledano and Zúñiga 2017), the lack of diagnostic characters to differentiate them (Armendáriz-Toledano et al. 2014a), and the coexistence of some of species in space and time in the same host (Zúñiga et al. 1995, 1999; Moser et al. 2005). This has led some collections of D. frontalis complex species to be incorrectly identified or unrecognized, despite species can be identified with molecular markers (e.g., COI mtDNA) (Victor and Zúñiga 2016), chromosomes number (Lanier et al. 1988, Armendáriz-Toledano et al. 2014a, 2017), and in some cases with cuticular hydrocarbon (Sullivan et al. 2012).

The morphology of the seminal rod, a sclerotized structure within the internal sac of the aedeagus, has been used succesfully to identify species belonging to the D. frontalis complex (Vité et al. 1974, 1975, Lanier et al. 1988, Armendáriz-Toledano et al. 2014a; Armendáriz-Toledano et al. 2015) and consequently used to reconsider their distribution (Armendáriz-Toledano et al. 2014b, 2017). In this study, we review the geographical distribution of D. brevicomis in the mountain systems of northern Mexico and perform a geometric morphometrics analysis of seminal rods to evaluate their reliability and consistency for identifying this species with regard to members of the D. frontalis complex.

Materials and Methods

More than 1,500 specimens of the D. frontalis complex species from 60 geographic locations in northern Mexico were reviewed; D. brevicomis was present in 31 of these locations (Table 1). The samples were collected directly from infested trees or donated by federal institutions: Comisión Nacional Forestal in Chihuahua, Durango, and Jalisco; Instituto Nacional de Investigaciones Forestales Agrícolas y Pecuarias (INIFAP) campus in Aguascalientes; Laboratorio de Análisis de Referencia en Sanidad Forestal del INIFAP; Colección Científica de Entomología Forestal, División de Ciencias Forestales, Universidad Autónoma de Chapingo; and Museo de Historia Natural de la Ciudad y Cultura Ambiental de la Ciudad de Mexico.

Table 1.

Species, acronyms, state, municipality, location, and geographical coordinates from examined specimens of D. brevicomis, D. approximatus, and D. adjunctus

| Sp | Acronims | State, municipality, and locality | Longitude | Latitude | Altitude (m) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| D. brevicomis | CGRA | Chihuahua, Guachochi-Rincones del Aguajito | 26°58′′12″ | 107°06′12″ | 2,441 |

| CGEC | Chihuahua, Guachochi-Ejido Corralitos | 26°54′40″ | 106°58′39″ | 2,417 | |

| CGA | Chihuahua, Guachochi-La Angostura | 26°56′56″ | 107°06′00″ | 2,440 | |

| CGRP | Chihuahua, Guachochi-Rocheachi, pesachi | 27°4′56″ | 107°12′3″ | 2,291 | |

| CGMA | Chihuahua, Guachochi-Mesa del Aguaje | 27°05′39″ | 107°15′18″ | 2,384 | |

| CGFL | Chihuahua, Guachochi-Frac. A, Lote 1, La Lobera | 26°53′2″ | 107°06′43″ | 2,475 | |

| CGTH | Chihuahua, Guachochi-Ejido Tatahuichi Hueleyvo | 27°15′34″ | 107°22′53″ | 2,303 | |

| CGTS | Chihuahua, Guachochi-Tonachi, Sibarichi. | 26°56′47″ | 107°15′29″ | 2,202 | |

| CGAT | Chihuahua, Guachochi-Ajolotes, Telesforo | 26°52′45″ | 107°02′29″ | 2,425 | |

| CGAP | Chihuahua, Guachochi-Aboreachi, Potrero Eusebio | 27°06′26″ | 107°20′15″ | 2,213 | |

| CGF4 | Chihuahua, Guachochi-Frac. 4 Rancho Roque. | 26°43′50″ | 107°10′33″ | 2,496 | |

| CGSA | Chihuahua, Guachochi-Samachique | 27°17′50″ | 107°32′51″ | 2,324 | |

| CGP | Chihuahua, Guachochi-El peñasco | 26°53′20″ | 107°05′41″ | 2,440 | |

| CGVL | Chihuahua, Guachochi-Valle de Lobos | 26°55′47″ | 107°08′23″ | 2,458 | |

| CGLS | Chihuahua, Guachochi-Ejido La Soledad | 26°56′55″ | 106°59′37″ | 2,330 | |

| CGRE | Chihuahua, Guachochi-Rancho La Esperanza | 26°52′40″ | 107°11′33″ | 2,492 | |

| CGL2 | Chihuahua, Guachochi-Lote 2 | 26°52′20″ | 107°08′37″ | 2,455 | |

| CGAZ | Chihuahua, Guachochi-Ejido Agua Zarca | 26°49′15″ | 107°08′11″ | 2,465 | |

| CGT | Chihuahua, Guachochi-El Tascate | 26°47′14″ | 107°07′34″ | 2,507 | |

| CGT2 | Chihuahua, Guachochi-Caborachi | 26°49′23″ | 106°55′39″ | 2,480 | |

| CGPE | Chihuahua, Guachochi-Patio Elio Acosta | 26°51′38″ | 107°5′12″ | 2,418 | |

| CML | Chihuahua, Madera-La Lobera | 29°37′25″ | 108°34′59″ | 1,946 | |

| CMG | Chihuahua, Madera-Guadalupe Victoria | 29°13′4″ | 107°53′20″ | 2,241 | |

| DSO | Durango, San Dimas-Ejido Otinapa y San Carlos | 24°02′26″ | 105°04′23″ | 2,485 | |

| DSC | Durango, San Dimas-Chavarría | 24°22′8″ | 105°32′48″ | 2,540 | |

| DPE | Durango, Durango-Parque Ecológico Tecúan | 23°56′60″ | 105°3′00″ | 2,456 | |

| DAM | Durango, Durango-Ejido Altares-Mesa del Cristo | 23°56′60″ | 105°13′43″ | 2,487 | |

| CAM | Coahuila, Arteaga-Monterreal | 24º14′8″ | 100º26′5″ | 2,209 | |

| NLG | Nuevo León, Galeana-Carretera Linares-Galeana la ‘Y’ | 24°46′45″ | 100°2′42″ | 1,607 | |

| NGP | Nuevo León, Galeana-Puerto Pastores | 24°46′42″ | 100°2′1″ | 1,584 | |

| NCP | Nuevo León, Cerro-‘El Potosí’ | 24°52′2″ | 100°13′52″ | 3,392 | |

| TGF | Tamaulipas, Goméz Farias-Ejido Unidos Venceremos | 22°52′18″ | 99°2′44″ | 1,110 | |

| EAFMa | Estado de México, Axapusco-Ejido Francisco I. Madero | 19°41′53″ | 98°45′19″ | 2,870 | |

| JCGT b | Jalisco, Ciudad Guzmán-Sierra del Tigre | 19°53′32″ | 102°58′11″ | 2,686 |

D. approximatus.

D. adjunctus.

D. frontalis complex species were identified following Armendáriz-Toledano and Zúñiga (2017). Specimens were sexed by the presence of frontal tubercles and stridulatory apparatus in males (Lyon 1958, Wood 1982). Male genitalia were removed from specimens and cleared according to Armendáriz-Toledano et al. (2014b). The seminal rod was separated from the genitalia, and both structures were semipermanently mounted on the same slide in glycerol and photographed in lateral view using a Nikon Coolpix 5000 (Nikon, Tokyo, Japan) camera on a phase contrast microscope (400×).

Geometric Morphometrics

In total, 70 images from seminal rods of D. brevicomis from 31 localities were analyzed (Table 1). In addition, for comparison purposes, 10 seminal rods of specimens from British Columbia, Canada and San Jacinto, California and Flagstaff, Arizona, United States were included in the analysis. Images from seminal rods of D. frontalis (n = 5), D. mesoamericanus (n = 4), D. mexicanus (n= 4), and D. vitei (n = 5) reported in Armendáriz-Toledano et al. (2014b) and images from D. adjunctus (n = 5) and D. approximatus (n = 4) seminal rods freshly obtained from specimens collected in Mexican localities (Table 1) were also included in the analysis. All images were identically oriented with the seminal valve pointing upwards (Fig. 1A).

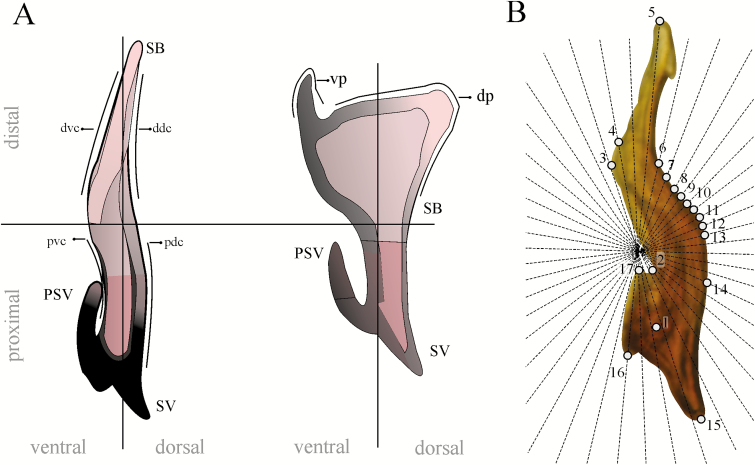

Fig. 1.

Lateral view of the seminal rod of D. brevicomis and D. mesoamericanus. (A) Anatomy of the entire (D. brevicomis) and bifurcade (D. mesoamericanus) seminal rod. (B) Seminal rod of D. brevicomis showing landmarks type II (1, 3, 15–17) and III (2), and semilandmarks. ddc (distal dorsal curvature); dp (dorsal process); dvc (distal–ventral curvature); pdc (proximal dorsal curvature); PSV (prolongation of seminal valve); pvc (proximal ventral curvature); SB (seminal rod body); SV (seminal valve).

Because there is an insufficient number of suitable, well-defined homologous points on the seminal rod, we used landmarks and semilandmarks (Bookstein 1991, Zelditch et al. 2004) (Fig. 1B). To guarantee a consistent location of semilandmarks on seminal rod curvatures, a fan of 46 radiating lines was added to each seminal rod image. The fan was digitalized in the MakeFan6 application in the integrated morphometrics package (IMP) (Sheets 2003), and the points where lines met with the margin of the seminal rod constituted semilandmarks. In total, 6 landmarks (type II [1, 3, 15–17] and III [2]) and 11 semilandmarks (4–14) were defined and later digitalized in an x, y coordinates matrix using the tpsDig program, ver 1.40 (Rohlf 2004).

Given that semilandmarks were digitized as discrete points, coordinate adjustment was done in SemiLand 6 (Sheets 2003) to minimize the tangential variation of points on seminal rod curvatures after generalized Procrustes analysis (GPA) (Zelditch et al. 2004). GPA was performed in the CoordGen6 program of IMP to produce a set of partial Procrustes superimpositions of specimens without effects of size, position or rotation.

To obtain new variables that quantify the highest percentage of shape variation, relative warps analysis (RWA) was performed in PAST 3.12 using the adjusted x, y coordinates matrix (Hammer et al. 2001, Zelditch et al. 2004). RWA was performed using paired variance–covariance matrices among species, and seminal rod shape variation in a multidimensional space was plotted using the first two relative warps (RW1 vs RW2).

Changes in seminal rod geometric configuration of the specimens were visualized by thin-plate spline deformation grids in PAST 3.12, and shape variation was visualized by mean of deformation grids.

Multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA), with respective post hoc pairwise Hotelling’s T-test, using the first five RWs (Zelditch et al. 2004), was performed to evaluate shape differences among species. The discriminatory power of seminal rod shape among species was tested using canonical variate analysis (CVA) with coordinates generated by Procrustes in PAST 3.12.

Results

Distribution Range

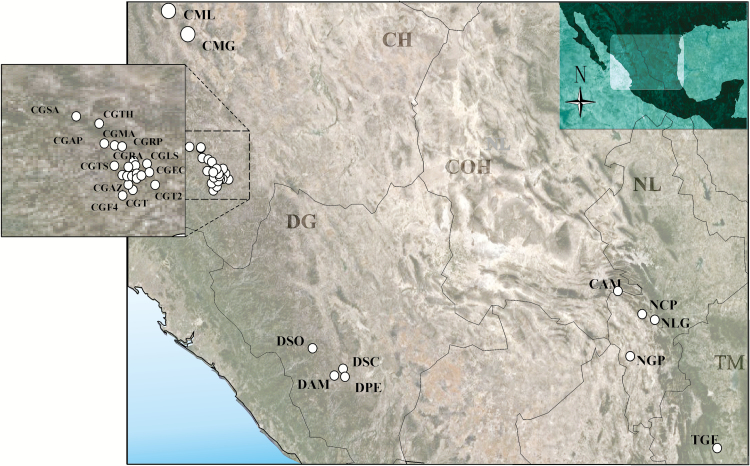

D. brevicomis was identified in the following localities in Mexico (Fig. 2, Table 1): Chihuahua, Guachochi municipality: Ricones del Aguajito, 26° 58′12″, 107° 06′12 (New record); Ejido Corralitos, 26° 54′40″, 106° 58′39″ (New record); La angostura, 26° 56′56″, 107° 06′0″ (New record); Rocheachi-Pesachi, 27° 4′56″, 107° 12′3″ (New record); Mesa del Aguaje, 27° 05′39″, 107° 15′18″ (New record); Fraccionamiento A, Lote 1, La lobera, 26° 53′2″, 107° 06′43″ (New record); Tatahuichi-Hueleyvo, 27° 15′34″, 107° 22′53″ (New record); Tonachi-Sibarichi, 26° 56′47″, 107° 15′29″ (New record); Ajolotes-Telesforo, 26° 52′45″, 107° 02′29″ (New record); Aboreachi-Potrero Eusebio, 27° 06′26″, 107° 20′15″ (New record); Fraccionamiento 4 Rancho Roque, 26° 43′50″, 107° 10′33″′(New record); Samachique, 27° 17′50″, 107° 32′51″′(New record); El Peñasco, 26° 53′20″, 107° 05′41″′(New record); Valle de Lobos, 26° 55′47″, 107° 08′23″′(New record); Ejido La Soledad, 26° 56′55″, 106° 59′37″′(New record); Rancho La Esperanza, 26° 52′40″, 107° 11′33″′(New record); Lote 2, 26° 52′20″, 107° 08′37″′(New record); Ejido Agua Zarca, 26° 49′15″, 107° 08′11″′(New record); El Tascate, 26° 47′14″, 107° 07′34″′(New record); Caborachi, 26° 49′23″, 106° 55′39″′(New record); Patio Elio Acosta, 26° 51′38”, 107° 5′12” (New record). Madera municipality: La Lobera, 29° 37′25″, 108° 34′59″′(New record), Guadalupe Victoria, 29° 13′4″, 107° 53′20″′(New record). Durango, San Dimas municipality: Ejido Otinapa y San Carlos, 24° 02′26″, 105° 04′23″′(New record), Chavarría, 24° 22′8″, 105° 04′23″′(New record). Durango municipality: Parque Ecológico Tecúan,, 23° 56′60”, 105° 3′00” (New record), Ejido Altares-Mesa del Cristo, 23° 56′60”, 105° 13′43″′(New record). Coahuila, Arteaga municipality: Monterreal, 24° 14′8″, 100º 26′5″. Nuevo León, Galeana municipality: Carretera Linares-Galeana, la “Y”, 24° 46′45”, 100° 2′42” (New record), Puerto Pastores, 24° 46′42″, 100° 2′1″′(New record), “Cerro el Potosí”, 24° 52′2”, 100° 13′52″′(New record). Tamaulipas, Gómez Farías municipality: Ejido unidos venceremos, 22° 52′18”, 99° 2′44”, (New state record).

Fig. 2.

Collection locations for D. brevicomis identified by morphometric analysis of the seminal rod, and the presence of homogeneous short pubescences on elytral declivity. Locality acronyms are shown in Table 1. CH (Chihuahua); DG (Durango); NL (Nuevo Leon); COH (Coahuila); TM (Tamaulipas).

Geometric Morphometrics

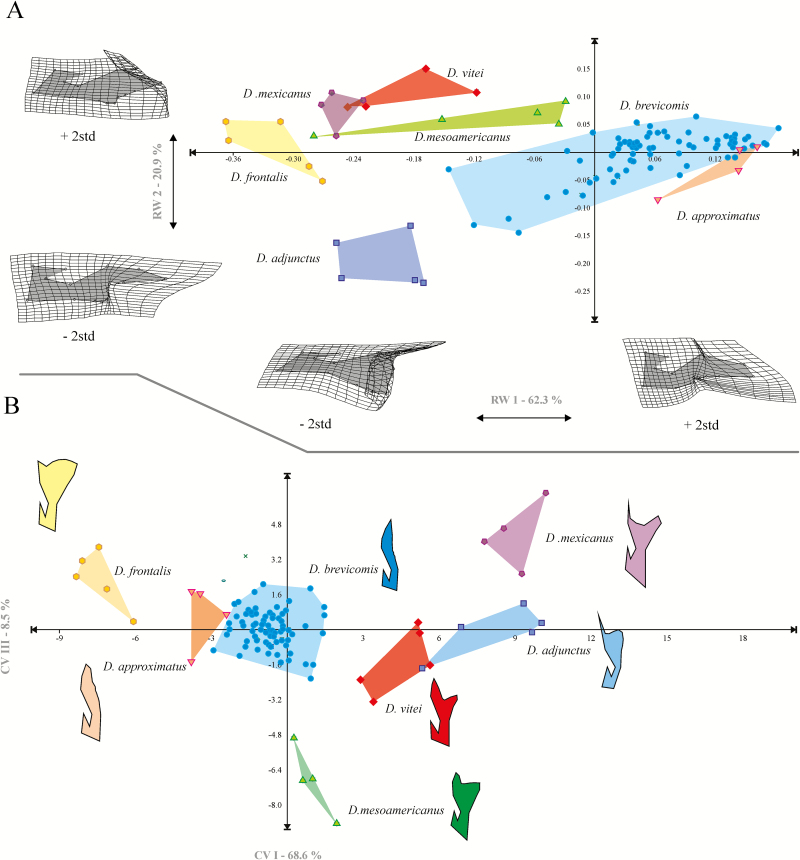

The first three RWs explained 98.3% of the observed total variation (RW1: 62.3%, RW2: 20.9%, RW3: 11.7%, RW4: 2.9%). The deformation grids corresponding to RW1 explained deformations in the distal region of the seminal rod, dorsal border and seminal valve. Specimens with positive RW1 values had a thin, whole distal area almost as wide as the seminal valve, whereas specimens with negative values had a much wider distal edge than the seminal valve and distal edge divided into ventral and dorsal proceses (Fig. 3A).

Fig. 3.

Scatter plots of RWs and CV of seminal rod shape of D. adjunctus, D. approximatus, D. brevicomis, D. frontalis, D. mexicanus, D. mesoamericanus, and D. vitei. (A) RW1 versus RW2, showing deformation grids corresponding to each component. (B) CV1 versus CV3 showing the mean shape configuration of each species.

RW2 showed deformations in the dorsal and ventral processess of the seminal rod, as well as in the curvature between both proceses and the degree of prominence of the curvature of the dorsal proximal region (Fig. 3A). Specimens with positive values for this component had a slightly longer ventral process than dorsal process. The curvature between both processes and the curvature of the distal proximal region were slightly convex, whereas specimens with negative values presented a ventral process much longer than the dorsal process, with the curvature between both processes evidently convex and with a highly developed curvature of the dorsal proximal region (Fig. 3A).

The scatter plot between RW1 and RW2 showed the formation of seven groups, four of them with a slight overlap, given that one specimen of D. vitei was mixed with D. mexicanus, and two specimens of D. approximatus were mixed with D. brevicomis (Fig. 3A).

Significant differences were found in the form of seminal rods among species (MANOVA: λWilks = 0.009578, F = 78.35, d.f. = 12,102, P ≤ 0.001). The respective paired Hotelling’s T-test supported differences in the shape of this structure between D. brevicomis and the rest of the analyzed species: D. adjunctus (P ≤ 0.001), D. approximatus (P ≤ 0.005), D. frontalis (P ≤ 0.001), D. vitei (P ≤ 0.001), D. mesoamericanus (P ≤ 0.001), and D. mexicanus (P ≤ 0.001).

The CVA explained 97.6% of total variation in the first three canonical vectors (CV1: 68.6%, CV2: 20.42%, CV3: 8.5%). Scatter plots between CV1 versus CV2, and CV1 versus CV3, and discriminant function correctly grouped and classified 100% of the specimens according to seven analyzed species (Fig. 3B).

Discussion

Range Distribution

Our study confirms the presence of D. brevicomis in Chihuahua, Coahuila, Durango, and Nuevo Leon states, where this species had been previously reported (Atkinson 2017, Lanier et al. 1988, Salinas-Moreno et al. 2010, Wood and Brigth 1992) and provides 30 new records in Mexico. Of these new records, 26 are in Chihuahua and Durango states in the Sierra Madre Occidental (SMOC) and four in Nuevo Leon and Tamaulipas states in the Sierra Madre Oriental (SMOR). The Tamaulipas record constitutes the most southern distribution site. Voucher representatives of all locations analyzed were deposited in the Museo de History Natural de la Ciudad y Cultura Ambiental and Colección Nacional de Insectos del Instituto de Biología, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México (CNIN), Mexico City, Mexico.

The increase in the records number of D. brevicomis suggests that its ocurrence in northern Mexico has often been overlooked, perhaps due to incorrect determination or because it is far less abundant compared with other D. frontalis complex species. We found that in >90% of analyzed samples, the WPB was present in small proportions (~1:100) compared with other bark beetles (e.g., D. mexicanus or D. frontalis).

The majority of D. brevicomis records in Canada and the United States has been reported in P. ponderosa Douglas ex Lawson 1836 and P. coulteri D. Don 1836 (Wood 1982, Lanier et al. 1988, Wood and Bright 1992, Six and Bracewell 2015) and occasionally in other species such as Pinus arizonica Engelmann ex Rothrock 1878 (Pinales: Pinaceae), and Abies concolor (Gordon et Glendinning) Hildebrand 1861 (Pinales: Pinaceae) (Atkinson 2017, Bright 1976). In Mexico, scarce records of this species were reported for Pinusestevesi Martinez 1982, Pinusengelmannii Carrière 1854, Pinusleiophylla Schiede ex Schlechtendal et Chamisso 1831, Pinusmontezumae Lambert 1832, and Pinusteocote Schiede ex Schlechtendal et Chamisso 1830 (Cibrián-Tovar et al. 1995, Salinas-Moreno et al. 2010). In this study, we found D. brevicomis in P. engelmannii, P. leiophylla, P. montezumae, and P. teocote.

The distribution of D. brevicomis in the northern regions of SMOC and SMOR in Mexico, its discontinuous range in both regions, and the larger number of hosts recorded compared with Canada and the United States should be used to reconsider the potential ecological role that this aggressive species might have in Mexico; in fact, in these last years the collection of this species have been more frequent in these mountain systems, altough outbreaks in these mountains have been attributed to other Dendroctonus species.

Geometric Morphometrics

Seminal rod shape has been proposed repeatedly as a useful morphological character for identifying D. frontalis complex species (Vité et al.1974, 1975; Lanier et al.1988). Recently, a quantitative analysis of this structure in individuals from species belonging to the D. frontalis complex (e.g., D. frontalis–D. mesoamericanus, D. mexicanus–D. vitei) comfirmed its reliablity for identifying and discriminating these species (Armendáriz-Toledano et al 2014a,b).

Our results show that when members of this complex are included as a group, the interspecific variation is so broad that it is not possible to recognize discrete groups for each species of the D. frontalis complex (Fig. 3A). The most evident segregation is observed for two large groups, one consisting of the taxa that present seminal rod bodies divided into ventral and dorsal processes (D. adjunctus, D. frontalis, D. mesoamericanus, D. mexicanus, and D. vitei) and the other constituted by species that possess the entire body (D. approximatus and D. brevicomis) (Fig. 3A).

RWA showed a slight overlap between D. mexicanus–D. vitei and D. approximatus–D. brevicomis, because these species present the most similar seminal rods (Fig. 3A). In fact, in the case of D. approximatus and D. brevicomis, previous authors have not recognized differences in this structure, characterizing it as “elongated” (Lanier et al. 1988). However, CVA did not show overlap in the seminal rod shape of these species (Fig. 3B), indicating that it is a useful diagnostic character for their identification. Particularly, these differences were consistent even after specimens of D. brevicomis from other localities were included.

Thus, D. brevicomis can be differentiated from D. approximatus by the presence of a thin distal area of the seminal rod body with very pronounced distal–dorsal and distal–ventral edges and seminal valves thinner than the seminal rod body.

Intraspecific Variation of the Seminal Rod of D. brevicomis

Our results show that the seminal rod displays a wide geographic variation in terms of size and shape (Fig. 4). Specimens from British Columbia and California have longer seminal rods than those from Arizona, which, in turn, are longer than those from SMOC (Chihuahua and Durango) specimens. Further, specimens from British Columbia and western California show seminal rods with scarcely pronounced elongated dorsal and ventral curvatures compared with specimens from eastern Arizona, which also have elongated seminal rods but conspicuosly pronounced dorsal and ventral curvatures. On the other hand, specimens from Mexican localities present more complex seminal rod shape patterns. Specimens from SMOR have thinner seminal rods than specimens from any other locality, with very pronounced curvatures.

Fig. 4.

Seminal rod in lateral view, representative of D. brevicomis across its distribution range. West (western side of the Great Basin (GB)); east (eastern side of GB); SMOR (Sierra Madre Oriental); SMOC (Sierra Madre Occidental).

Other attributes of taxonomic value (e.g., pubescence length in elitral declivity) in the WPB show variation patterns similar to those of seminal rods. Specimens from British Columbia and California present variable pubescence length in elitral declivity that does not exceed interestriae width, while specimens from Arizona, Chihuahua, Durango, and Nuevo Leon display a more uniform pubescence length. Additional studies of these and other morphological characteristics across all distribution range of D. brevicomis must be performed to determinate the limits of this species, because morphological, molecular, and chemical ecology evidence (Hopkins 1909; Kelley et al. 1999; Pureswaran et al. 2008, 2016) suggests the presence of cryptic species between western and eastern populations of the Great Basin in the United States and possibly also in Mexican populations.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Jorge E. Macías-Sámano and three anonymous reviewers for their comments and suggestions on this manuscript. This study was partially funded by the Secretaría de Investigación y Posgrado IPN (20144216). O.V.M. and F.A.T. were Consejo Nacional de Ciencia y Tecnología (CONACyT) fellows 267732 and 267436, respectively. F.A.T. was also member of Programa Institucional de Formación de Investigadores of Instituto Politécnico Nacional (PIFI-IPN).

References Cited

- Armendáriz-Toledano F., Niño A., Sullivan B. T., Macías-Sámano J., Victor J., Clarke S. R., and Zúñiga G.. 2014a. Two species within Dendroctonus frontalis (Coleoptera: Curculionidae): evidence from morphological, karyological, molecular and crossing studies. Ann. Entomol. Soc. Am. 107: 11–27. [Google Scholar]

- Armendáriz-Toledano F., Niño A., Macías-Sámano J. E., and Zúñiga G.. 2014b. Review of the geographical distribution of Dendroctonus vitei (Curculionidae: Scolytinae) based on geometric morphometrics of the seminal rod. Ann. Entonmol. Soc. Am. 107: 748–755. [Google Scholar]

- Armendáriz-Toledano F., Niño A., Sullivan B. T., Kirkendall L. R., and Zúñiga G.. 2015. A new species of bark beetle, Dendroctonus mesoamericanus sp. nov. (Curculionidae: Scolytinae), in Southern Mexico and Central America. Ann. Entomol. Soc. Am. 108: 403–414. [Google Scholar]

- Armendáriz-Toledano F., and Zúñiga G.. 2017. Illustrated key to species of genus Dendroctonus (Curculionidae Scolytinae) occurring in Mexico and Central America. J. Insect Sci. 17: 34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armendáriz-Toledano F., García-Román J., López M. F., Sullivan B. T., and Zúñiga G.. 2017. New characters and redescription of Dendroctonus vitei (Curculionidae: Scolytinae). Can. Entomol. 140: 413–433 [Google Scholar]

- Atkinson T. H. 2017. Bark and ambrosia beetles www.barkbeetles.info (accesed 20 January 2017).

- Bright D. E. 1976. The insects and arachnids of Canada. Part II. The Bark beetles of Canada and Alaska (Coleoptera: Scolitydae). Biosystematics Research Institute, Canada Department of Agriculture; Ottawa, Ontario, Canada. [Google Scholar]

- Bookstein F. L. 1991. Morphometrics tools for landmark data: geometry and Biology. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cibrián-Tovar D., Méndez-Montiel J. T., Campos-Bolaños R., Yates H. O. III, and Flores-Lara J.. 1995. Insectos forestales de México/Forest Insects of Mexico. Universidad Autónoma de Chapingo, México. [Google Scholar]

- DeMars C. J., and Roettgering B. H.. 1982. Western pine beetle. Forest Service and Disease Leaflet I. USDA Forest Service. [Google Scholar]

- Hammer O., Harper D., and Ryan P.. 2001. Paleontological statistics software package for education and data analysis. Paleontol. Electro. 4: 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Hopkins A. D. 1909. Contributions toward a monograph of the scolytid beetles I, the genus Dendroctonus. U.S. Department of Agriculture Bureau of Entomology Technical Series 17 (Part I). [Google Scholar]

- Kelley T. S., Mitton J. B., and Paine T. D.. 1999. Strong differentitation in mitochondrial DNA of Dendroctous brevicomis (Coleoptera: Scolytidae) on different subspecies of ponderosa pine. Ann. Entomol. Soc. Am. 92: 193–197. [Google Scholar]

- Lanier G. N., Hendrichs J. P., and Flores J. E.. 1988. Biosystematics of the Dendroctonus frontalis (Coleoptera: Scolytidae) complex. Ann. Entomol. Soc. Am. 81: 403–418. [Google Scholar]

- Lyon R. L. 1958. A useful secondary sex character in Dendroctonus bark beetles. Can. Entomol. 90: 582–584. [Google Scholar]

- Miller J. M., and Keen F. P.. 1960. Biology and control of the Western Pine Beetle. USDA Forest Service Miscellaneous. Publication 800, Washington, DC. Department of Agriculture; 831 p. [Google Scholar]

- Moser J. C., Fitzgibbon B. A., and Klepzig K. D.. 2005. The Mexican pine beetle, Dendroctonus mexicanus: first record in the United States and co-occurrence with the southern pine beetle – Dendroctonus frontalis (Coleoptera: Scolytidae or Curculionidae: Scolytinae). Entomol. News 116: 235–243. [Google Scholar]

- Perusquía O. J. 1978. Descortezador de los pinos (Dendroctonus spp.). Taxonomía y distribución. Instituto Nacional de Investigaciones Forestales. Boletín Técnico No. 55. SARH. DGICF; México. [Google Scholar]

- Pureswaran D. S., R. W. Hofstetter, and Sullivan B. T.. 2008. Attraction of the southern pine beetle, dendroctonus frontalis, to pheromone components of the western pine beetle, dendroctonus brevicomis (Coleoptera: Curculionidae: Scolytinae), in an allopatric zone. Environ. Entomol. 37: 70–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pureswaran D. S., R. W. Hofstetter B. T. Sullivan A. M. Grady, and Brownie C.. 2016. Western pine beetle populations in Arizona and California differ in the composition of their aggregation pheromones. J. Chem. Ecol. 42: 404–413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rohlf F. J. 2004. tpsDig. Version 1.40. Stony Brook, NY: Deparment of Ecology and Evolution, State University of New York. [Google Scholar]

- Salinas-Moreno Y., Guadalupe Mendoza M. A., Barrios M. A., Cisneros R., Macías-Sámano J., and Zúñiga G.. 2004. Aerography of the genus Dendroctonus (Coleoptera: Curculionidae: Scolytinae) in Mexico. J. Biogeogr. 31: 1163–1177. [Google Scholar]

- Salinas-Moreno Y., Vargas C. F., Zúñiga G., Víctor J., Ager A., and Hayes J. L.. 2010. Atlas de distribución geográfica de los descortezadores del género Dendroctonus (Curculionidae: Scolytinae) en México/Atlas of the geographic distribution of bark beetles of the genus Dendroctonus (Curculionidae: Scolytinae) in Mexico. Instituto Politécnico Nacional-Comisión Nacional Forestal, México. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez-Martínez G., Torres-Espinoza L. M., Vázquez-Collazo I., González-Gaona E., and Narváez-Flores R.. 2007. Monitoreo y manejo de insectos descortezadores de coníferas. INIFAP-Campo Experimental Pabellón. Libro técnico No. 4. [Google Scholar]

- Sheets H. D. 2003. IMP – integrated morphometrics package. Buffalo, NY: Department of Physics, Canisius College; (http://www3.canisius.edu/_sheets/imp7.htm). [Google Scholar]

- Six D. L., and Bracewell R.. 2015. Dendroctonus, pp. 305–350. InVega F.E. and Hofstetter R.W. (eds.), Bark beetles, biology and ecology of native and invasive species. Academic Press. Amsterdam (The Netherlands) and Boston (MA), Elsevier. [Google Scholar]

- Strom B. L., Goyer R. A., and Shea P. J.. 2001. Visual and olfactory disruption of orientation by the western pine beetle to attractant-baited traps. Entomol. Exp. Appl. 100: 63–67. [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan B. T., Niño A., Moreno B., Brownie C., Macías-Sámano J., Clarke S. R., Kirkendall L. R., and Zúñiga G.. 2012. Biochemical evidence that Dendroctonus frontalis consists of two sibling species in Belize and Chiapas, Mexico. Ann. Entomol. Soc. Am. 105: 817–831. [Google Scholar]

- Swaine J. M. 1918. Canadian bark beetles, Part II. A preliminary classification with an account of the habits and means of controls. Can. Dept. Agr. Tech. Bull., 14. [Google Scholar]

- Victor J., and Zúñiga G.. 2016. Phylogeny of Dendroctonus bark beetles (Coleoptera: Curculionidae: Scolytinae) inferred from morphological and molecular data. Syst. Entomol. 41: 162–177. [Google Scholar]

- Vité J. P., Islas S. F., Renwich J. A. A., Hughes P. R., and Kliefoth R. A.. 1974. Biochemical and biological variation of southern pine beetle population in North and Central America. Z. Angew. Entomol. 75: 422–435. [Google Scholar]

- Vité J. P., Hughes R. F., and Renwich J. A. A.. 1975. Pine beetles of the genus Dendroctonus: pest population in Central America. FAO. Bull. Plant Prot. 6: 178–184. [Google Scholar]

- Wood S. L. 1963. A revision of the bark beetles genus Dendroctonus Erichson (Coleoptera: Scolytidae). Great Basin Nat. 23: 1–117. [Google Scholar]

- Wood S. L. 1982. The bark ambrosia beetles of North and Central America (Coleoptera: Scolytidae): a taxonomic monograph. Great Basin Nat. 6: 1–1359. [Google Scholar]

- Wood S. L., and Bright D. E.. 1992. A catalog of Scolytidae and Platipodidae (Coleoptera), Part 2: taxonomic index. Great Basin Nat. 13: 1–833. [Google Scholar]

- Zelditch L. M., Swiderski D. L., Sheets H. D., and Fink W. L.. 2004. Geometric morphometrics for biologist: a primer. Maple Vail; New York, NY. [Google Scholar]

- Zúñiga G., R. Cisneros, and Salinas-Moreno Y., 1995. Coexistencia de Dendroctonus frontalis Zimmerman y D. mexicanus Hopkins (Coleóptera: Scolytidae) sobre un sobre un mismo hospedero. Acta Zool. Méx. (n.s.) 64: 59–62. [Google Scholar]

- Zúñiga G., Mendoza-Correa G., Cisneros R., and Salinas-Moreno Y.. 1999. Zonas de sobreposición geográfica de las especies mexicanas de Dendroctonus Erichson (Coleoptera: Scolytidae) y sus implicaciones ecológico-evolutivas. Acta Zool. Méx. (n.s.) 77: 1–22. [Google Scholar]