Abstract

Objective

Open communication about cancer diagnosis and relevant stress is frequently avoided among breast cancer survivors in China. Non-disclosure behavior may lead to negative psychological consequences. We aimed to examine the relationship between non-disclosure and depressive symptoms, and the role of coping strategies and benefit-finding in that relationship among Chinese breast cancer survivors.

Methods

Using convenience sampling, we recruited 148 women in an early survivorship phase (up to 6 years post-treatment) in Nanjing, China. Participants were asked to complete a set of questionnaires in Chinese language, regarding sociodemographic characteristics, depressive symptoms, disclosure views, coping strategies, and benefit-finding.

Results

A higher level of non-disclosure was associated with more depressive symptoms. This relationship was mediated by self-blame and moderated by benefit-finding. Specifically, non-disclosure was associated with depressive symptoms through self-blame. The impact of non-disclosure was minimized among the women with a higher level of benefit-finding.

Conclusion

Unexpressed cancer-related concern may increase self-blame, which leads to emotional distress among Chinese breast cancer survivors. Practicing benefit-finding may reduce the negative impact of non-disclosure. As a culturally appropriate way of disclosure, written expression may be beneficial to Chinese breast cancer patients.

Keywords: non-disclosure, coping, depressive symptom, breast cancer, oncology, China

Disclosure is defined as the extent to which patients talk openly about their diagnosis and illness-related thoughts and feelings to people in their social networks.1,2 On the other hand, non-disclosure is often used to refer to non-expression, emotional control, inhibition, or topic avoidance. A growing body of research documents that non-disclosure is associated with poor psychological adjustment, elevated distress, and decreased quality of life among cancer patients.1,3 Compared with patients who express negative emotion, cancer patients who restrain from expressing their negative emotions are more likely to be anxious, depressed, and confused after being given the diagnosis.4

Breast cancer patients in China have reported strong reluctance to reveal their diagnosis, treatment, and illness-related thoughts and feelings to outsiders (acquaintances or distant relatives),5 those between outsiders and insiders (nurses and doctors),6 and sometimes, even to close family members and friends.7 Compared with individuals in Western society, Chinese in general are less likely to disclose their feelings and thoughts. This may be because Chinese culture values collectivism and social harmony over individual expression.8 In Chinese culture, displaying strong emotions is considered a weakness and was traditionally even thought to be a cause of illness.8 The cultural values of emotional restraint and harmony have been associated with reluctance to solicit support from family and friends, not wanting to lose face, and inviting criticism.9 Additionally, influenced by Chinese philosophical and medical beliefs, many patients attributed their cancer to factors such as the imbalance between yin and yang, fate, karma, geomancy, and misfortune.10 This cultural belief also may be associated with patients’ unwillingness to disclose their illness and reluctance to discuss cancer-related issues with others. Despite the strong tendency of non-disclosure in Chinese culture, relatively little is known about adjustment of Chinese breast cancer patients in the context of non-disclosure and the ways in which non-disclosure may lead to emotional distress in this population.

The social-cognitive processing (SCP) model of adjustment to stressors11 illustrates the impact of non-disclosure on emotional distress among patients with cancer. The SCP model suggests that non-disclosure may hinder adjustment to cancer by interrupting the cognitive processing of traumatic or stressful life events, particularly in unsupportive or critical social conditions.12,13 According to the SCP, traumatic or stressful events, including cancer diagnosis and treatment, may cause emotional distress through challenging the individual’s pre-existing mental models of themselves and the world. Thus, emotional adaptation could be achieved by re-evaluating worldviews and re-establishing psychological equilibrium. Disclosing stressful events and discussing relevant thoughts and feelings with others may provide the opportunity to improve understanding of reality and integrate the cognitive discrepancy by receiving new information and/or obtaining appropriate support,14 which in turn, may facilitate emotional adjustment. In contrast, non-disclosure may undermine an individual’s ability to confront and process the events to make sense of their life situation. The limited confrontation or incomplete cognitive processing may lead individuals to experience intrusive thoughts12 or ineffective cognitive strategies, such as denial or self-blame,15 which have consistently been found to cause distress.16,17

The SCP model and relevant research suggest that when women do not share their experience and feelings externally with others, certain types of coping strategies are likely to be activated and driven to deal with the experience and feelings by themselves. When the coping strategies driven by non-disclosure are ineffective, patients may experience emotional distress, while, effective coping strategies may lead to better adjustment. This is consistent with research on coping and emotional adjustment.

Research on coping and emotional adjustment among women with breast cancer has demonstrated that different types of coping efforts predict various levels of adaptation.18,19 In general, avoidance or passive coping styles have been associated with increased emotional distress and frequently have been described as maladaptive, whereas approaching or active coping styles have been associated with better psychological and social outcomes and commonly described as adaptive among women with breast cancer of various ethnicities, including Chinese.20,21 More specifically, acceptance and positive reappraisal were reported to be beneficial in reducing depressive symptoms, whereas self-blame was detrimental to emotional well-being among women with breast cancer in China.22,23 In addition to the role as a predictor of emotional well-being, coping has been conceptualized as a mediator in the relationship between interpersonal dynamics and emotional wellbeing during health-related stressful experiences.16,17 To date, a few studies have supported a role of intrusive thought as a mediator in the relationship between non-disclosure and adjustment to cancer.24,25 However, the potential mediating effects of coping strategies on the impact of non-disclosure rarely have been tested. Therefore, in the present study, we explored the mediating role of coping strategies in the relationship between non-disclosure and depressive symptoms.

Although non-disclosure may mobilize certain coping strategies associated with emotional distress, this does not eliminate the possibility that patients that do not share their challenges engage in internal efforts to understand their situation and successfully establish coherent meaning of self and situations. Successful finding of meaning or benefit from adversity, including cancer diagnosis,26 which is often termed benefit-finding, can be conceptualized as consequences of individuals’ attempts to re-establish a coherent view of the world and self during the stressful events.27 Benefit-finding has been reported to be prevalent for a significant portion of cancer patients, including Chinese cancer survivors and negatively related to anxiety, depression, and other psychological distress over time.28,29 Because it is possible that women’s internal efforts to find meaning and benefit interact with non-disclosure and buffer the negative effects of non-disclosure on depressive symptoms,30 our study examined the moderating role of benefit-finding, as well as the mediating role of coping strategies.

Based on previous research and theories, we postulated that: (1) non-disclosure would be associated with depressive symptoms controlling for demographics and illness related variables; (2) coping strategies would mediate the relationship between non-disclosure and depressive symptoms; and (3) benefit-finding would moderate the relationship between non-disclosure and depression among breast cancer patients in China.

METHODS

The present study was conducted as part of an international research collaboration between the Center for Asian Health (CAH) at Temple University in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania (United States) and the Nanjing Cancer Survivors Association (NCSA) in China. The CAH offered guidance in protocol development and research methods and the NCSA played a central role in study implementation, including participant recruitment and data collection. In addition to the onsite training by the Principal Investigator (Dr Grace X. Ma), regular conference calls were conducted between the PI’s research team members of CAH and NCSA to discuss recruitment procedures, progress in data collection, and interpretation of the findings.

Study Participants and Recruitment Procedures

Breast cancer survivors who are members of NCSA in China were recruited between September 2013 and March 2014. Patients were eligible for study participation if they: (1) completed treatment for early stage breast cancer (stage 0–III); (2) were aged 21 years or older; (3) had completed treatment for breast cancer within the past 6 years (because this study focused on early survivorship phase); (4) had no other history of cancer; and (5) were able to provide informed consent. Women were recruited through NCSA’s member community outreach events, newsletters, and survivor support groups. With the permission from NCSA leader, the research staff attended outreach events and support groups held by the NCSA to introduce the study to survivors. Eligible women interested in participating were provided with a consent form and self-administered questionnaire to return in a self-addressed stamped envelope. The NCSA also advertised the study with contact information in its newsletter so that interesting women could contact the research staff. Study participation was voluntary without compensation. A total of 148 women participated in the study.

Measures

Demographic and disease-related variables

We collected demographic information, including age, marital/relationship status, employment status, annual household income, insurance status, and years of formal education. We provided participants with information about disease-related characteristics, such as cancer stage and time since treatment.

Depressive symptoms

The 9-item Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) was used to measure depressive symptoms.31 The PHQ-9 consists of one item for each of the 9 DSM-IV depression criteria: (1) anhedonia; (2) depressed mood; (3) trouble sleeping; (4) feeling tired; (5) change in appetite; (6) guilt or worthlessness; (7) trouble concentrating; (8) feeling slowed down or restless; and (9) suicidal thoughts. The measure was used for both establishing a provisional diagnosis and grading symptom severity. For this study, PHQ-9 was used to measure severity of depressive symptoms with a 4-point scale from 0 (not at all) to 3 (nearly every day) and a total score ranging from 0 to 27. The PHQ was validated with a Chinese population,32 with a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.78 in this study.

Disclosure questionnaire

A 4-item disclosure questionnaire was adapted from the measure designed to assess the reasons why Asians and Asian Americans might avoid seeking social support for coping with stressors.33 The questionnaire was modified for this study to examine patients’ beliefs that might affect their willingness to communicate about their cancer status and relevant stress. The 4 items represent: (1) desire to preserve the harmony of the social group (ie, “although having breast cancer bothers me, I would not want to disrupt my social group by sharing it.”); (2) belief that telling others would make the situation worse (ie, “I would rather not tell about my stress or problems of breast cancer to my friends because they would blow them out.”); (3) desire to save face and avoid embarrassment (ie, “it is better to keep one’s concerns to one’s self, rather than lose face in front of the people I am close to.”); and (4) belief that each person has a responsibility to solve problems on their own. All 4 items were measured on a 5-point scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). The overall score ranged from 4 to 20, with a high score indicating a stronger tendency of non-disclosure. The 4 items had acceptable internal consistency reliability (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.70).

Coping

Coping skills were assessed using the Brief COPE scale,34 a 28-item coping inventory. The Brief COPE scale has previously been validated in Chinese populations with success. It measures 14 conceptually different coping reactions (denial, disengagement, self-blame, positive reappraisal, acceptance, planning, self-distraction, use of emotional support, use of instrumental support, active coping, humor, religion, venting, and substance use). Participants rated how often they employed a certain strategy as a way of coping with stress related to their cancer-related experiences. Responses are measured on a 4-point scale, from 1 (I have not been doing this at all) to 4 (I have been doing this a lot). Internal consistency reliability was 0.79 as measured by Cronbach’s alpha.

Benefit-finding

A 6-item instrument adapted from the Benefit Finding Scale35 was used. The statement for each item is “[H]aving breast cancer…” followed by a potential benefit gained from the experience. Examples include “has led me to be more accepting of things” and “has brought my family closer together.” Items were scored on a 5-point scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). Although the original Benefit Finding Scale has 17-items, more recent studies have used scales consisting of 10 items,36 or even 3 items.37 One study has demonstrated cultural difference of factor structure of benefit-finding scale items between Japanese and Western populations, highlighting the necessity to use culturally-appropriate scales of benefit-finding. 38 The final selection of the Benefit Finding Scale items was based on the feedback and pilot-testing with the NCSA’s advisors and patient focus groups to ensure its cultural relevance and appropriateness. In the present sample, the 6-item benefit-finding scale had an internal consistency reliability of 0.80 as measured by Cronbach’s alpha.

Data Analysis

Descriptive analysis was used to describe the sample characteristics and prevalence of variables of interest. The relationships of demographics, cancer-related variables, and other psychosocial variables (non-disclosure, coping, benefit-finding) with depressive symptoms, the main outcome variable of the study, were examined by conducting ANOVA and correlation analyses. The variables that showed significant association with depressive symptoms were included in the regression analyses as covariates.

The main analyses consisted of a series of regression analyses to determine the association between non-disclosure and depressive symptoms, as well as the moderating and mediating roles of cognitive coping strategies and benefit-finding in that association. To test moderating effects of benefit-finding, a hierarchical regression analysis was performed with demographic covariates, non-disclosure, potential moderator, and interactions term being entered in each step. An interaction term was created using the centered predictor and moderator variables to minimize potential problems with multicollinearity. To test mediating effects of cognitive coping on depressive symptoms, regression analyses were conducted to test each of the following conditions: (1) significant associations between non-disclosure and depressive symptoms, non-disclosure and potential mediating variables, and potential mediating variables and depressive symptoms; and (2) significant reduction in the effect of non-disclosure on depressive symptoms when mediating variables are controlled for. In addition, a bias-corrected bootstrap procedure was used to calculate 95% confidence intervals to determine the significance of the indirect effect of the potential mediator.39

RESULTS

Characteristics of the Sample

One hundred forty-eight women with a mean age of 54 years participated in the study. The majority of the women were married (91%), had earned a high school degree (67%), were retired (70%), reported an annual household income less than 60,000 RMB (equivalent to $9645 USD) (89%), and had health insurance (98%). According to the National Bureau of Statistics of China, households with an annual income ranging from 60,000 RMB to 500,000 RMB are classified as middle class, which means that the majority of the women in this study were from relatively low-income households in China. Regarding cancer-related characteristics, most of the women had been diagnosed with stage II breast cancer (64%) and had completed treatment with both surgery and chemotherapy (89%). Slightly more than a half of the women (51%) were within 1 3 years post-treatment, and more than three-fourths (78%) had been receiving follow-up care every 6 months.

To identify potential covariates, we tested the relationship between depressive symptoms and each of the demographic and disease-related variables reported above using correlation or analysis of variance as appropriate. Education level and insurance status were significantly associated with depressive symptoms (Table 1). However, 98% of the women sampled were insured, and only education level was included in the subsequent regression analyses as a covariate.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics for Demographics and Disease-related Variables, and Their Associations with Depressive Symptoms (N = 148)

| N (%) | p-value of association with depressive symptoms | |

|---|---|---|

| Age (M, SD) | 54.1 (7.39) | .84 |

|

| ||

| Marital status | ||

|

| ||

| Married/living as married | 134 (90.5) | .82 |

| Divorced/separated | 8 (5.4) | |

| Windowed | 6 (4.1) | |

|

| ||

| Annual household incomea | 0.48 | |

|

| ||

| Less than 30K RMB | 53 (35.8) | |

| B/w 30K and 60K RBM | 68 (45.9) | |

| More than 60K RMB | 16 (10.8) | |

| Missing | 11 (7.4) | |

|

| ||

| Highest education | .02 | |

|

| ||

| Below high school | 48 (32.4) | |

| High school | 66 (44.6) | |

| College or higher | 33 (22.3) | |

| Missing | 1 (1.0) | |

|

| ||

| Employment | .70 | |

|

| ||

| Employed | 21 (14.1) | |

| Unemployed | 18 (12.1) | |

| Retired | 103 (69.8) | |

| Homemaker | 6 (4.0) | |

|

| ||

| Insurance | .04 | |

|

| ||

| No | 3 (2.0) | |

| Yes | 145 (98.0) | |

|

| ||

| Stage of cancer | .56 | |

|

| ||

| Stage 0 | 4 (2.7) | |

| Stage I | 40 (27.0) | |

| Stage II | 94 (63.5) | |

| Stage III | 10 (6.8) | |

|

| ||

| Years after treatment completion | .64 | |

|

| ||

| Within a year | 32 (21.6) | |

| 1–3 years | 75 (50.7) | |

| 3–6 years | 41 (27.7) | |

Note.

= Annual household income was reported in RMB (Chinse yuan), the official currency is equal to 0.15 US dollar in January 2016.

Prevalence and Correlation of Main Variables

The mean PHQ-9 depressive symptoms score was 5.9 (SD = 3.7) on the PHQ-9, suggesting a degree of mild depression (Table 2). Regarding the first 2 screening questions, approximately 70% of the women reported experiencing “little interest or pleasure in doing things” and 40% reported “feeling down, depressed or hopeless” at least several days during the past 2 weeks.

Table 2.

Correlations between Main Variables

| Depressive symptoms | Non-disclosure | Mean | SD | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Depressive symptoms | - | 5.86 | 3.65 | |

| Non-disclosure | 0.246** | - | 3.23 | 0.79 |

| Benefit finding | −0.216* | 0.123 | 4.15 | 0.51 |

| Denial | 0.075 | 0.271** | 2.15 | 1.04 |

| Self-blame | .0423** | 0.296** | 1.78 | 0.87 |

| Positive reappraisal | 0.139 | −0.005 | 3.36 | 0.77 |

| Acceptance | −0.120 | 0.020 | 3.46 | 0.63 |

| Disengagement | 0.103 | 0.260** | 1.58 | 0.79 |

| Planning | 0.212* | 0.151 | 2.86 | 0.82 |

| Self-distraction | 0.106 | 0.016 | 3.32 | 0.86 |

| Use of emotional support | 0.152 | 0.133 | 2.73 | 0.91 |

| Use of instrumental support | 0.134 | 0.037 | 2.93 | 0.87 |

| Active coping | 0.118 | 0.159 | 3.12 | 0.79 |

| Humor | −0.223* | −0.003 | 3.38 | 0.64 |

| Religion | 0.107 | 0.142 | 2.09 | 1.02 |

| Venting | 0.180* | 0.177* | 2.47 | 0.68 |

| Substance use | −0.017 | 0.049 | 1.07 | 0.25 |

p < .05,

p < .01, 2-tailed

A large proportion of the participant pool “agreed” or “strongly agreed” that they would not share their diagnosis, concerns, or problems such that they could avoid disrupting their social group (64%), save face (53%), solve the problems on their own (53%), and avoid making the situation worse (29%). The mean scores on this variable (M = 3.23, SD = 0.8) suggested the general tendency of non-disclosure of the sample. Women reported relatively high levels of benefit-finding (M = 4.1, SD = 0.4) At least 80% of the women “agreed” or “strongly agreed” on all 6 of the items.

Zero-order correlations were conducted to examine the relationships between depressive symptoms and other main variables, including non-disclosure, benefit-finding, and 14 coping strategies. The results, presented in Table 2, indicate that depressive symptoms were associated with non-disclosure (r = 0.246, p < .01), benefit-finding = −0.216, p < .05), self-blame (r = 0.423, p < .01), planning (r = 0.212, p < .05), humor (r = −0.223, p < .05), and venting (r = 0.180, p < .05). Non-disclosure was significantly associated with depressive symptoms (r = 0.246, p < .01), denial (r = 0.271, p < .01), self-blame (r = 0.296, p < .01), disengagement (r = 0.260, p < .01), and venting (r = 0.177, p < .05).

Association between Non-disclosure and Depressive Symptoms

The prediction of non-disclosure on depressive symptoms was examined after controlling for demographic and disease-related covariates. As Table 3 shows, non-disclosure significantly predicted depressive symptoms (β = 0.253, p < .05), controlling for education in Model 1, and education and non-disclosure accounted for 6.7% of the variance in depressive symptoms.

Table 3.

Regression Models Predicting Depressive Symptoms with Potential Moderator

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | p | β | p | β | p | |

| Covariate | ||||||

| Education | 0.103 | < .001 | 0.104 | .199 | 0.083 | .291 |

| Independent variable | ||||||

| Non-disclosure (ND) | 0.253 | .003 | 0.283 | .001 | 1.676 | < .001 |

| Moderator | ||||||

| Benefit finding (BF) | −0.248 | .003 | 0.323 | .098 | ||

| Interaction term | ||||||

| ND × BF | −1.591 | .002 | ||||

| R2 | 0.067 | 0.127 | 0.190 | |||

Mediating Role of Maladaptive Coping Strategies

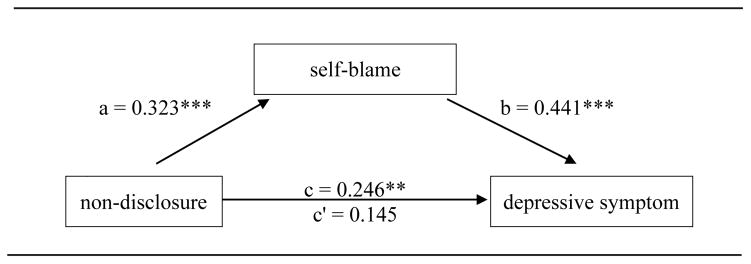

Among the different scales of coping strategies, only venting and self-blame were significantly associated with both non-disclosure and depressive symptoms (Table 1). Thus, the 2 variables were included in the mediation analysis. In the mediation model, non-disclosure was significantly associated with self-blame (β = 0.323, p < .001), which was significantly associated with a higher level of depressive symptoms (β = 0.441, p < .001). When self-blame was added, the regression coefficient between non-disclosure and depressive symptoms was reduced (β = 0.246 to β = 0.145) and the association was no longer statistically significant (p > .05). This model explained 21.5% of the variance in depressive symptoms (R2 = 0.215). The significance of indirect effect was tested using bootstrapping procedures, and unstandardized effects and 95% confidence interval (CI) were computed for each of 1000 bootstrapped sample. The results showed that the indirect effect of non-disclosure on depressive symptoms through self-blame was statistically significant (unstandardized coefficient B = 0.52, 95% CI 0.22 – 0.97). Figure 1 illustrates the mediation model with unstandardized regression coefficients. The other potential mediator, venting, did not significantly mediate the relationship between non-disclosure and depressive symptoms.

Figure 1.

Mediation Pathway of Non-Disclosure on Depressive Symptoms

*p < .05; **p < .01; ***p < .001

Note. a, b, c, and c′ are an unstandardized regression coefficient; c is the coefficient without self-blame in the model, and c′ is the coefficient with self-blame in the model.

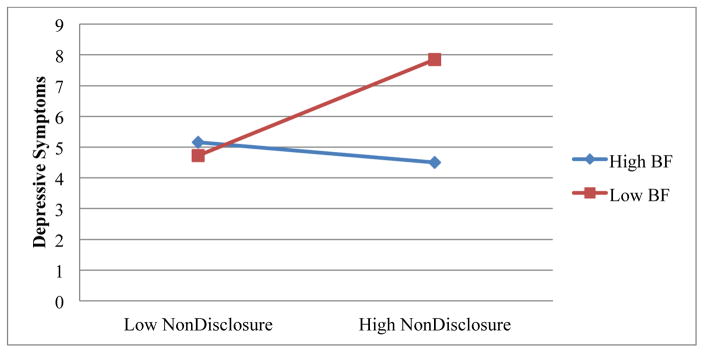

Moderating Role of Benefit-finding

To test the moderating role of benefit-finding, we tested the interaction effect between non-disclosure and benefit-finding. As Table 3 shows, we added the moderating variable, benefit-finding, in Model 2, and, the interaction term “ND × BF,” in Model 3. Results showed that the interaction effect between non-disclosure and benefit-finding was statistically significant β = −1.591, p < .01), in addition to the main effect of non-disclosure (β = 1.676, p < .001). The final model explained 19.0% of the variance in depressive symptoms. Figure 2 illustrates the slopes for the relation between non-disclosure and benefit-finding plotted at low (1 SD below the M) and high (1 SD above the M) levels of variables. The statistical significance of the 2 slopes was tested to interpret the simple effect of non-disclosure at both levels of benefit-finding. The result of a simple effect analysis indicated that the relation between non-disclosure and depressive symptoms was statistically significant at a low level of benefit-finding (β = 0.45, p < .001), but not so at a high level of benefit-finding. These results suggest that the impact of non-disclosure on depressive symptoms is substantial among women who experience low levels of benefit-finding, whereas the impact of non-disclosure is minimal among those who experience high levels of benefit-finding.(unstandardized coefficient

Figure 2.

Interaction Effect of Non-disclosure and Benefit Finding (BF) on Depressive Symptoms

DISCUSSION

The present study examined the relationship between non-disclosure of cancer-related stress and concern and depressive symptoms among the breast cancer survivors in China, and the role of coping strategies and benefit-finding in that relationship. As hypothesized, non-disclosure was significantly associated with depressive symptoms, controlling for demographics and disease-related factors, which is consistent with previous studies demonstrating the negative impact of non-disclosure or non-expression of stress-related thoughts and feelings on depressive symptoms.1,40

Self-blame appears to be one mechanism by ( which non-disclosure is associated with depressive symptoms among breast cancer survivors in China. Women who do not share their diagnosis and relevant concerns are more likely to blame themselves, which can lead to an increased risk of depressive symptoms. This finding is consistent with a US study that found a mediating role of self-blame in the link between cancer-related topic avoidance and psychological distress among women who were undergoing treatment, or had recently completed treatment, for breast cancer.15 Evidence that self-blame mediates the link between non-disclosure and depressive symptoms among survivors of breast cancer in China adds to current literature regarding the impact of coping strategies on emotional well-being among patients with breast cancer. As the SCP model suggests, women who fail to make sense of their cancer through open discussion may be overwhelmed by intrusive thoughts of responsibility and guilt.11 Specifically, Chinese women may blame themselves for their cancer because in China, breast cancer is still often thought to be contagious and a death sentence.6,7

In addition to the mediating role of self-blame, we found that benefit-finding was a moderator that serves as a protective factor in the relationship between non-disclosure and depressive symptoms. We hypothesized that some women who chose not to disclose their breast cancer-related feelings and thoughts might still engage in certain adaptive cognitive process and changes, such as benefit-finding, to deal with cancer-related stress, which could impact depressive symptoms. Results of our analysis confirmed the moderating effect of benefit-finding on the relationship between non-disclosure and depressive symptoms. Specifically, for breast cancer patients who found less benefit from their illness, failing to disclose is related to elevated depressive symptoms. However, if patients utilize a high level of benefit-finding, non-disclosure does not have a significant effect on depressive symptoms. Our findings are consistent with previous studies that demonstrated a positive impact of benefit-finding on depressive symptoms among Chinese breast cancer patients.41 Our findings also add to the benefit-finding literature by expanding the role of benefit-finding in the context of non disclosure.

Although only self-blame was found to be a significant mediator, the relationships of other coping strategies with non-disclosure and depressive symptoms are noteworthy. Denial and behavioral disengagement were significantly associated with non-disclosure. However, they were not significantly associated with depressive symptoms. These results indicate that non-disclosing women are likely to deny their current conditions or give up dealing with them, yet, the coping strategies would not necessarily lead to depressive symptoms in this population.

Interestingly, planning, one of the coping strategies, an action previously demonstrated to be adaptive in dealing with emotional distress, was associated with increased depressive symptoms along with venting and self-blame. A potential explanation would be that a woman’s “trying to come up with a strategy about what to do” or “thinking hard about what steps to take” may represent a situation where the woman is experiencing uncertainty or lack of confidence about what to do to deal with her situation. Because coping is a complex and dynamic process,42 it is possible that, in this population, the planning may be mobilized with other maladaptive coping strategies, as well as adaptive coping strategies, which leads to increased depressive symptoms. Indeed, the planning is significantly correlated with venting and self-blame, in addition to active coping and positive reappraisal in the correlation analysis (not presented in the table). This is consistent with mobilization effects43 in which severe stress may prompt individuals to increase their coping, whether adaptive or mal-adaptive.

The complexity of coping process might have contributed to the results that only humor was negatively associated with depressive symptoms, and other coping strategies that have been demonstrated to be adaptive in dealing with stress were not correlated with depressive symptoms. Although benefit-finding appeared to buffer the impact of non-disclosure and was associated with reduced depressive symptom, positive reappraisal, a conceptually similar coping strategy, was not associated with depressive symptoms. It would be because benefit-finding reflects actual successful identification and recognition of benefits bestowed by cancer-related experiences, whereas positive reappraisal refers to the ongoing and not necessarily successful, efforts of looking for new meanings. Patients’ unsuccessful attempts to reappraise their stressful situations would not be sufficient to reduce depressive symptoms.

The findings of our study have several clinical implications. In Chinese cultural contexts, expression of stress-related feelings and thoughts to others may not necessarily be beneficial, especially when it is perceived to be disrupting social harmony. An alternative form of disclosure that has received considerable scholarly attention is written disclosure, or expressive writing. Meta-analysis results have confirmed the beneficial impacts of expressive writing on psychological well-being.44 In addition, Lu and Stanton found that healthy Asian adults benefited more from expressive writing than did their Caucasian peers, suggesting that written disclosure might be a more culturally sensitive or appropriate form of expression for Asian individuals.45 Lu et al22 also argued that because it does not involve direct interpersonal contact, written disclosure provides an assurance of privacy and facilitates emotional expression without damaging the harmonious social relationships. Their study results indicated a significant association between expressive writing and long-term improvement of psychological well-being among Chinese breast cancer survivors. Our findings of the mediating and moderating effects suggest that rather than directly targeting non-disclosure, it would be more efficient to address the cognitive coping strategies such as self-blame and benefit-finding. In particular, written disclosure interventions to promote benefit-finding and reduce self-blame may have a synergic effect in facilitating cognitive processing to restore self-esteem and sense of meaning in this population.

This study has several limitations. First, the cross-sectional nature of this study precludes any causal inference. Although self-blame fully mediated the link between non-disclosure and depressive symptoms, it is also possible that higher depressive symptoms may lead to more self-blame, which in turn leads to non-disclosure. To confirm the direction of the mediating effects, future research needs to apply a longitudinal design that allows researchers to examine changes of coping strategies at different time periods to capture the entirety of the process. Second, the convenience sampling design may have limited the representativeness of the sample because the participants in this study may be different from women that did not participate. It is possible that women who experienced no or mild symptoms would be more likely to participate in the study than those who experienced more severe depressive symptoms. Future studies with a larger sample of patients with a wide range of depressive symptom would be beneficial in capturing a more precise understanding about the relationships among non-disclosure, coping, and depressive symptoms. A third limitation involves that the non-disclosure scale used in the present study has not been validated in existing literature. However, the 4 items we used in the present study showed satisfactory internal reliability and were conceptually consistent with previous findings of emotional disclosure among Chinese individuals. The validity of these specific items, particularly for Chinese individuals, merits future research. Finally, detailed information on the women’s social networks and source of social support was not provided in the present study. Traditionally, Chinese women have served as the main caregiver of family members and a source of support for others rather than being a target for support.46 Therefore, recognizing the social environment of women and the people women can rely on would be important in understanding women’s disclosure and coping behaviors. Future studies are strongly recommended to include the information to elucidate Chinese women’s adjustment to cancer-related stressors.

Despite the limitations, to the best of our knowledge, this is the first study that demonstrates the importance of and interrelations among non-disclosure, coping strategies, benefit-finding, and depressive symptoms in breast cancer survivors in China. This study sheds light on the issues surrounding how breast cancer patients in China face burdens of not sharing information about their diagnosis to their family and friends. Our findings provide important suggestions for more culturally sensitive interventions.

Conclusion

Our findings indicate that non-disclosure is associated with more depressive symptoms among breast cancer survivors in China. Unexpressed cancer related concern may increase self-blame, which leads to emotional distress among breast cancer survivors in China. However, practicing benefit-finding may reduce the negative impact of non-disclosure. Our results suggest that disclosure needs to be situated in sociocultural contexts. Specifically, in Chinese cultural contexts, expression of stress-related feelings and thoughts to others may not necessarily be beneficial, especially when it is perceived to be disrupting social harmony. Written expression may be a more culturally appropriate way of emotion disclosure and beneficial to patients with breast cancer in China. Other coping strategies including denial and behavioral disengagement are associated with non-disclosure. Planning and venting are positively and humor is negatively associated with depressive symptom. The impact of complex and dynamic coping process on emotional adjustment in this population warrants further investigation.

Human Subjects Statement

We conducted this study according to the guidelines laid down in the Declaration of Helsinki. The Temple University Institutional Review Board approved all procedures involving human participants. Participants gave consent prior to taking the survey.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the partners, volunteers, community coordinators of Asian Community Health Coalition and Nanjing Cancer Survivor Association and research team at the Center for Asian Health, Temple University, who facilitated and supported the data collection of the study. This research was partially supported by faculty research funds (PI: Dr Grace X. Ma), NIH U54 CA153513 Asian Community Cancer Health Disparities Center (PI: Dr Grace X. Ma), and NIH R03TW009406 Fogarty International Center (PI: Dr Grace X. Ma).

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

Contributor Information

Minsun Lee, Postdoctoral Associate, Center for Asian Health, Lewis Katz School of Medicine, Philadelphia, PA.

Yuan Song, Nanjing Cancer Survivor Association, Nanjing, China.

Lin Zhu, Postdoctoral Associate, Center for Asian Health, Lewis Katz School of Medicine, Philadelphia, PA.

Grace X. Ma, Associate Dean for Health Disparities, Director of Center for Asian Health, Laura H. Carnell Professor and Professor in Clinical Sciences, Lewis Katz School of Medicine, Temple University, Philadelphia, PA.

References

- 1.Figueiredo MI, Fries E, Ingram KM. The role of disclosure patterns and unsupportive social interactions in the well-being of breast cancer patients. Psychooncology. 2004;13:96–105. doi: 10.1002/pon.717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yoo GJ, Aviv C, Levine EG, et al. Emotion work: disclosing cancer. Support Care Cancer. 2009;18:205–215. doi: 10.1007/s00520-009-0646-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Goldsmith DJ, Miller LE, Caughlin JP. Openness and avoidance in couples communication about cancer. In: Beck CS, editor. Communication Yearbook. Vol. 31. New York, NY: Routledge; 2009. pp. 62–117. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Iwamitsu Y, Shimoda K, Abe H, et al. Differences in emotional distress between breast tumor patients with emotional inhibition and those with emotional expression. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2003;57:289–294. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1819.2003.01119.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Liu J-E, Mok E, Wong T. Perceptions of supportive communication in Chinese patients with cancer: experiences and expectations. J Adv Nurs. 2005;52:262–270. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2005.03583.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tam Ashing K, Padilla G, Tejero J, Kagawa-Singer M. Understanding the breast cancer experience of Asian American women. Psychooncology. 2003;12:38–58. doi: 10.1002/pon.632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wong-Kim E, Sun A, DeMattos MC. Assessing cancer beliefs in a Chinese immigrant community. Cancer Control J Moffitt Cancer Cent. 2003;10:22–28. doi: 10.1177/107327480301005s04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wu DYH, Tseng W-S. Introduction: the characteristics of Chinese culture. In: Tseng W-S, Wu DYH, editors. Chinese Culture and Mental Health. Orlando, FL: Academic Press; 1985. pp. 3–13. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chang J. The interplay between collectivism and social support processes among Asian and Latino American college students. Asian Am J Psychol. 2015;6:4–14. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yeo SS, Meiser B, Barlow-Stewart K, et al. Understanding community beliefs of Chinese-Australians about cancer: initial insights using an ethnographic approach. Psychooncology. 2005;14:174–186. doi: 10.1002/pon.831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lepore SJ. A social-cognitive processing model of emotional adjustment to cancer. In: Baum A, Andersen BL, editors. Psychosocial Interventions for Cancer. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2001. pp. 99–116. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lepore SJ, Revenson TA. Social constraints on disclosure and adjustment to cancer. Soc Personal Psychol Compass. 2007;1:313–333. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zakowski SG, Ramati A, Morton C, et al. Written emotional disclosure buffers the effects of social constraints on distress among cancer patients. Health Psychol. 2004;23:555–563. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.23.6.555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Munro H, Scott SE, King A, Grunfeld EA. Patterns and predictors of disclosure of a diagnosis of cancer. Psy-chooncology. 2015;24:508–514. doi: 10.1002/pon.3679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Donovan-Kicken E, Caughlin JP. Breast cancer patients’ topic avoidance and psychological distress: the mediating role of coping. J Health Psychol. 2011;16:596–606. doi: 10.1177/1359105310383605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Culver JL, Arena PL, Antoni MH, Carver CS. Coping and distress among women under treatment for early stage breast cancer: comparing African Americans, Hispanics and non-Hispanic whites. Psychooncology. 2002;11:495–504. doi: 10.1002/pon.615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dunkel-Schetter C, Feinstein LG, Taylor SE, Falke RL. Patterns of coping with cancer. Health Psychol. 1992;11:79–87. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.11.2.79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hack TF, Degner LF. Coping responses following breast cancer diagnosis predict psychological adjustment three years later. Psychooncology. 2004;13:235–247. doi: 10.1002/pon.739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Scott JL, Kim W, Ward BG. United We Stand? The effects of a couple-coping intervention on adjustment to early stage breast or gynecological cancer. J Consult Clin Psy-chol. 2004;72:1122–1135. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.72.6.1122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang F, Liu J, Liu L, et al. The status and correlates of depression and anxiety among breast-cancer survivors in eastern China: a population-based, cross-sectional case control study. BMC Public Health. 2014;14:326. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-14-326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang X, Wang S-S, Peng R-J, et al. Interaction of coping styles and psychological stress on anxious and depressive symptoms in Chinese breast cancer patients. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev APJCP. 2012;13:1645–1649. doi: 10.7314/apjcp.2012.13.4.1645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li J, Lambert VA. Coping strategies and predictors of general well-being in women with breast cancer in the People’s Republic of China. Nurs Health Sci. 2007;9:199–204. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2018.2007.00325.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang Y, Yi J, He J, et al. Cognitive emotion regulation strategies as predictors of depressive symptoms in women newly diagnosed with breast cancer. Psychooncology. 2014;23:93–99. doi: 10.1002/pon.3376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lepore SJ. Expressive writing moderates the relation between intrusive thoughts and depressive symptoms. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1997;73:1030–1037. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.73.5.1030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.You J, Lu Q. Social constraints and quality of life among Chinese-speaking breast cancer survivors: a mediation model. Qual Life Res. 2014;23:2577–2584. doi: 10.1007/s11136-014-0698-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nezlek JB, Kuppens P. Regulating positive and negative emotions in daily life. J Pers. 2008;76:561–580. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.2008.00496.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Janoff-Bulman R. Shattered Assumptions: Towards a New Psychology of Trauma. New York, NY: Free Press; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ho SMY, Chan CLW, Ho RTH. Posttraumatic growth in Chinese cancer survivors. Psychooncology. 2004;13:377–389. doi: 10.1002/pon.758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Liu J-E, Wang H-Y, Wang M-L, et al. Posttraumatic growth and psychological distress in Chinese early-stage breast cancer survivors: a longitudinal study. Psychooncology. 2014;23:437–443. doi: 10.1002/pon.3436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Helgeson VS, Reynolds KA, Tomich PL. A meta-analytic review of benefit finding and growth. J Consult Clin Psy-chol. 2006;74:797–816. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.74.5.797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JBW. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16:606–613. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yeung A, Fung F, Yu S-C, et al. Validation of the patient health questionnaire-9 for depression screening among Chinese Americans. Compr Psychiatry. 2008;49:211–217. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2006.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Taylor SE, Sherman DK, Kim HS, et al. Culture and social support: who seeks it and why? J Pers Soc Psychol. 2004;87:354–362. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.87.3.354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Carver CS. You want to measure coping but your protocol’ too long: consider the brief cope. Int J Behav Med. 1997;4:92–100. doi: 10.1207/s15327558ijbm0401_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tomich PL, Helgeson VS. Is finding something good in the bad always good? Benefit finding among women with breast cancer. Health Psychol. 2004;23:16–23. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.23.1.16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jansen L, Hoffmeister M, Chang-Claude J, et al. Benefit finding and post-traumatic growth in long-term colorectal cancer survivors: prevalence, determinants, and associations with quality of life. Br J Cancer. 2011;105:1158–1165. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2011.335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Brand C, Barry L, Gallagher S. Social support mediates the association between benefit finding and quality of life in caregivers. J Health Psychol. 2016;21:1126–1136. doi: 10.1177/1359105314547244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ando M, Morita T, Hirai K, et al. Development of a Japanese benefit finding scale (JBFS) for patients with cancer. Am J Hosp Palliat Med. 2011;28:171–175. doi: 10.1177/1049909110382102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.MacKinnon DP. Introduction to Statistical Mediation Analysis. New York, NY: Routledge; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pennebaker JW, Kiecolt-Glaser JK, Glaser R. Disclosure of traumas and immune function: health implications for psychotherapy. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1988;56:239–245. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.56.2.239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wang Y, Zhu X, Yi J, et al. Benefit finding predicts depressive and anxious symptoms in women with breast cancer. Qual Life Res. 2015;24:2681–2688. doi: 10.1007/s11136-015-1001-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Folkman S, Lazarus RS. The relationship between coping and emotion: implications for theory and research. Soc Sci Med. 1988;26:309–317. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(88)90395-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pargament KI, Smith BW, Koenig HG, Perez L. Patterns of positive and negative religious coping with major life stressors. J Sci Study Relig. 1998;37:710–724. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Frattaroli J. Experimental disclosure and its moderators: a meta-analysis. Psychol Bull. 2006;132:823–865. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.132.6.823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lu Q, Stanton AL. How benefits of expressive writing vary as a function of writing instructions, ethnicity and ambivalence over emotional expression. Psychol Health. 2010;25:669–684. doi: 10.1080/08870440902883196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhan HJ. Through gendered lens: explaining Chinese caregivers’ task performance and care reward. J Women Aging. 2004;16:123–142. doi: 10.1300/J074v16n01_09. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]