Abstract

Two chronic dietary studies, conducted years apart, with ammonium perfluorooctanoate (APFO) in Sprague Dawley rats have been previously reported. Although both included male 300 ppm dietary dose groups, only the later study, conducted in 1990–1992 by Biegel et al., reported an increase in proliferative lesions (hyperplasia and adenoma) of the acinar pancreas. An assessment of the significance of the differences between both studies requires careful consideration of: the diagnostic criteria for proliferative acinar cell lesions of the rat pancreas (for example, the diagnosis of pancreatic acinar cell hyperplasia versus adenoma is based on the two-dimensional size of the lesion rather than distinct morphological differences); the basis for those criteria in light of their relevance to biological behavior; and the potential diagnostic variability between individual pathologists for difficult-to-classify lesions. A pathology peer review of male exocrine pancreatic tissues from the earlier study, conducted in 1981–1983 by Butenhoff et al., was undertaken. This review identified an increase in acinar cell hyperplasia but not adenoma or carcinoma in the earlier study. Both studies observed a proliferative response in the acinar pancreas which was more pronounced in the study by Biegel et al. Definitive reasons for the greater incidence of proliferative lesions in the later study were not identified, but some possible explanations are presented herein. The relevance of this finding to human risk assessment, in the face of differences in the biological behavior of human and rat pancreatic proliferative lesions and the proposed mechanism of formation of these lesions, are questionable.

Keywords: Perfluorooctanoate, PFOA, Pancreas, Pathology, APFO, Rats

1. Introduction

The ammonium salt of perfluorooctanoic acid (APFO, CASRN 3825-26-1) has been used commercially as a surface-active agent in the production of various fluoropolymers. APFO has been demonstrated to activate the xenosensor nuclear receptor NR1C1 (the peroxisome proliferator activated receptor α, or PPAR α) and is therefore a member of a class of compounds known as peroxisome proliferators.

The extensive toxicology database for this chemical has been reviewed [1], [2], and includes two chronic (2-year) dietary studies in Sprague Dawley rats conducted several years apart in different laboratories [3], [4]. Results of a study conducted in 1981–1983 were reported by Butenhoff et al. [4], and those of the other study, conducted in 1990–1992, were reported by Biegel et al. [3]. The Biegel et al. study was undertaken to investigate the modes of action of selected effects of APFO observed in the study reported by Butenhoff et al., with emphasis on changes in response over a chronic dosing period. Although there were some differences in the study protocols between the two studies, common to both studies was a group of male Sprague Dawley rats fed AFPO at a dietary concentration of 300 ppm (∼14 mg/kg-d) for 2 years. Results for the male groups at this concentration were similar between the two studies for most endpoints evaluated. However, one difference noted was the presence of treatment-related increases in the incidences of proliferative lesions (hyperplasia and adenoma) of pancreatic acinar cells in the Biegel et al. study that were not observed in the Butenhoff et al. study. The presence of an APFO treatment-related increase in pancreatic acinar cell hyperplasia and adenoma in the Biegel et al. study was consistent with the observed pancreatic effects of a number of known peroxisome proliferators [5].

To better understand the apparent difference between the two studies with respect to pancreatic acinar cell lesions, pancreatic tissues from the Butenhoff et al. study, which reported no effect on the exocrine pancreas, were re-evaluated microscopically. This peer review evaluated proliferative acinar cell lesions of the pancreas using the currently recommended diagnostic criteria for pancreatic acinar cell lesions in rodents [6], criteria which became available in the interim between the two studies and were used in the evaluation of the Biegel et al. study. In addition, it involved a pathologist common to both studies in order to enhance the diagnostic consistency between the two studies.

This paper uses this rigorous scientific approach to examine the collection of pancreatic tissues from two published studies to look for commonalities and differences using currently recommended pathology diagnostic criteria in a manner that neutralizes potential diagnostic variability between studies. In doing so, it was concluded that the pancreas is indeed a target for APFO and that the responses in the two studies reflect the spectrum of changes from normal to adenoma with those in one study being more advanced (both in incidence and in terms of lesion size). Thus, there is no need to separate the two studies as if the findings in this tissue are contradictory, as has been largely done to this point in review literature. This report provides the results of that microscopic review and discusses the significance of the differences seen between the two chronic studies in rats with APFO with respect to proliferative lesions of pancreatic acinar cells.

2. Methods

Two chronic dietary toxicity studies were performed with APFO in Sprague Dawley rats: the study reported by Butenhoff et al. (hereafter referred to as Study 1) was conducted at 3M Company (Riker Laboratories, St. Paul, MN, April 1981–May 1983), and the study reported by Biegel et al. (hereafter referred to as Study 2) was conducted at DuPont (Haskell Laboratory, Newark, DE, December 1990–December 1992). These studies have been previously reported [3], [4].

In Study 1, male and female rats were fed 0, 30 and 300 ppm APFO and sacrificed at 2 years (terminal sacrifice). This study also included a 1-year interim sacrifice for the 0 and 300 ppm groups only. The pathology results as reported by the study pathologist for Study 1 were not peer reviewed at the time although selected slides were subjectively reviewed at a later date [4].

Study 2 was conducted in male rats only and included a group fed 300 ppm APFO and two 0 ppm control groups: an ad libitum control group and a control group pair-fed to the APFO-fed group. There were multiple interim sacrifices in this mechanistic study, and the results from those evaluations are reported by Biegel et al. [3]. The current report will compare the results of the re-evaluation of Study 1 with the published results of the core study of Study 2, where rats were sacrificed following up to 2-years dietary exposure to APFO. The pathology results as reported by the study pathologist for Study 2 were previously peer reviewed by a second pathologist.

For the current report, a limited pathology peer review of Study 1 was conducted on formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded, hematoxylin & eosin stained sections of all available pancreatic tissues from male rats (two slides from the 300 ppm terminal sacrifice group were deemed to contain insufficient pancreas tissues hence they were not included in the review). The review pathologist for this re-evaluation (SRF) had served as the primary pathologist on Study 2, thus providing one reviewer common to both studies. In addition, any differences in diagnoses of proliferative acinar cell lesions between the study and review pathologists of Study 1 were also examined by a second reviewing pathologist (JMCR). The updated results reported herein for Study 1 reflect agreement between the two reviewing pathologist (the study pathologist for Study 1 was not available to participate in this review). Since the pathology results from Study 2 had already undergone a pathology peer review, further evaluation of pancreatic tissue from that study was not conducted, and the results of that study as given herein are as originally reported by Biegel et al. [3]. Also, since Study 2 did not include females, female pancreatic tissue from Study 1 was not included in the current review. Proliferative lesions of the exocrine pancreas were not reported in female rats in Study 1 [4].

Criteria used for the diagnosis of pancreatic acinar hyperplasia, adenoma and carcinoma were those recommended by Hansen et al. [6]. Namely, acinar proliferative lesions diagnosed as hyperplasia were well-delineated, generally oval lesions composed of closely packed acinar cells with slightly enlarged nuclei arranged in an elongated acinar pattern. Mitoses and apoptotic cells were occasionally seen. The diagnosis of adenoma was ascribed to lesions that appeared similar morphologically to hyperplastic lesions, yet were greater than 5 mm in diameter. The diagnosis of carcinoma was assigned to proliferations that had morphologic indicators of malignancy: namely, areas of poor differentiation, fibroplasia, necrosis, capsular or vascular invasion and/or high mitotic rate.

For both studies, incidences of acinar cell hyperplasia and neoplasia in the treated and control groups were compared for statistical significance as judged at P ≤ 0.05. The statistical analysis for the data from Study 2 was reported by Biegel et al. [3]. For the data created by peer review of Study 1 as reported in this manuscript, the statistical analysis included the Fisher's exact test and the Cochran–Armitage test for trend.

3. Results

For most pancreases evaluated from Study 1, the reviewing pathologists were in agreement with the study pathologist. Exceptions included several instances of pancreatic acinar cell hyperplasia observed by the review pathologists that were not reported as part of the original microscopic evaluation (Table 1; Fig. 1A and B). These occurred predominantly in the 300 ppm group but were also observed in control rats (Table 1). In addition, two instances (2/15) of acinar cell hyperplasia were seen in the 300 ppm interim sacrifice group (not included in Table 1) and one lesion originally identified as acinar cell hyperplasia in a 30 ppm rat was considered to be a basophilic focus of cellular alteration. Further, one male rat in the 300 ppm group was considered to have an acinar cell carcinoma, which was not previously diagnosed (Fig. 2A and B); however, the presence of this lesion is of uncertain relationship to treatment given its single incidence. The spontaneous incidence of acinar cell carcinoma is less than 1% in male rats of this strain [7], [8], [9].

Table 1.

Comparison of incidence of pancreatic acinar cell hyperplastic and neoplastic observations between the chronic dietary studies (at 2 years unless otherwise indicated) in rats fed ammonium perfluorooctanoate (APFO) as reported by Butenhoff et al. [4], pre-and post-review, and Biegel et al. [3].

| Butenhoff et al. [4] (Study 1) |

Biegel et al. [3] (Study 2) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 30 ppm APFO | 300 ppm APFO | Control | Pair-fed control | 300 ppm APFO | |

| Hyperplasia (H) | ||||||

| Initial review | 0/46 (0) | 2/46 (4) | 2/49 (4) | 14/80 (18)a | 8/79 (10) | 30/76 (39)# |

| Post-reviewb | 3/46 (7) | 1/46 (2) | 10/47c (21)* | |||

| Adenoma (A) | ||||||

| Initial review | 0/46 (0) | 0/46 (0) | 0/49 (0) | 0/80 (0) | 1/79 (1) | 7/76 (9)# |

| Post-review | 0/46 (0) | 0/46 (0) | 0/47c (0) | |||

| Carcinoma (C) | ||||||

| Initial review | 0/46 (0) | 0/46 (0) | 0/49 (0) | 0/80 (0) | 0/79 (0) | 1/76 (1) |

| Post-review | 0/46 (0) | 0/46 (0) | 1/47c (2) | |||

| Combined (H + A + C) | ||||||

| Initial review | 0/46 (0) | 2/46 (4) | 2/49 (4) | 14/80 (18) | 9/79 (11) | 38/76 (50)# |

| Post-review | 3/46 (7) | 1/46 (2) | 11/47c (23)* | |||

Rats with finding/rats examined (%).

Represents the consensus diagnosis following review post-study.

During the pathology re-evaluation of Butenhoff et al. study, two slides were deemed to contain insufficient pancreas tissues hence they were not included in the review.

Significantly different from pair-fed control group (p < 0.05).

Positive by Cochran–Armitage trend test (p < 0.05).

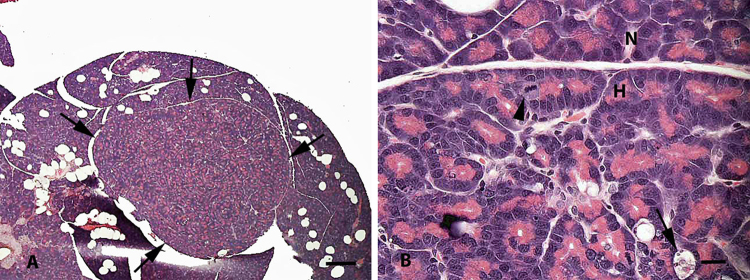

Fig. 1.

Pancreas from a control male rat (Study 1). (A) Low magnification of a well-circumscribed area of acinar cell hyperplasia (arrows). Bar = 500 μm. (B) Higher magnification of (A) at border of hyperplastic (H) and normal (N) regions. Areas of hyperplasia have crowding of acinar cell nuclei, some elongation and branching of acinar units, increased mitoses (arrowhead), and areas of apoptosis and dropout of acinar cells (arrow). Bar = 20 μm.

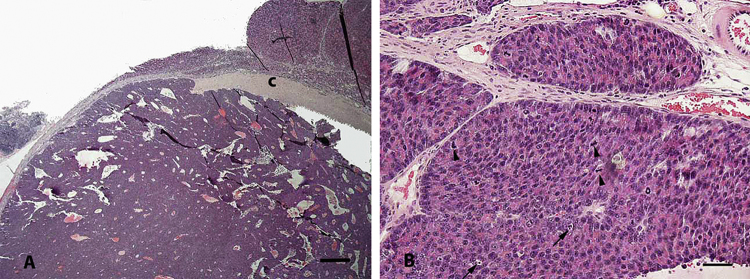

Fig. 2.

Pancreas from a male rat fed 300 ppm APFO (Study 1). (A) Low magnification of an acinar cell carcinoma partially encapsulated by fibrous tissue (c). Bar = 500 μm. (B) Higher magnification of (A) showing neoplastic acinar cells arranged in solid sheets or irregular tubules with frequent mitoses (arrowheads) and apoptosis (arrows). Bar = 50 μm.

Based on the results of the peer review of the pancreases in Study 1, the incidence of pancreatic acinar cell hyperplasia was statistically significantly elevated in the 300 ppm group as compared to controls. However, with respect to acinar cell tumors, the conclusions of the peer review were in agreement with the original study report in that there were no statistically significant or test substance-related increases in acinar cell neoplasms (adenoma or carcinoma) following chronic dietary exposure to 30 or 300 ppm APFO in Study 1.

4. Discussion

Only two studies to date have assessed chronic dietary exposure to APFO in rats. Although many of the endpoints assessed in these studies were collaborative, one observation that appeared to not be common to both studies was the finding of increased pancreatic acinar proliferations. This apparent contradiction was addressed in this study via a rigorous scientific approach that examined the collection of pancreatic tissues from both studies to look for commonalities and differences using currently recommended pathology diagnostic criteria in a manner that enhanced the diagnostic consistency between the studies. In doing so, it was concluded that the pancreas is indeed a target for APFO and that the responses in the two studies reflect the spectrum of changes from normal to adenoma with those in one study being more advanced (both in incidence and in terms of lesion size). Thus, there is no need to separate the two studies as if the findings in this tissue are contradictory, as has been largely done to this point in review literature.

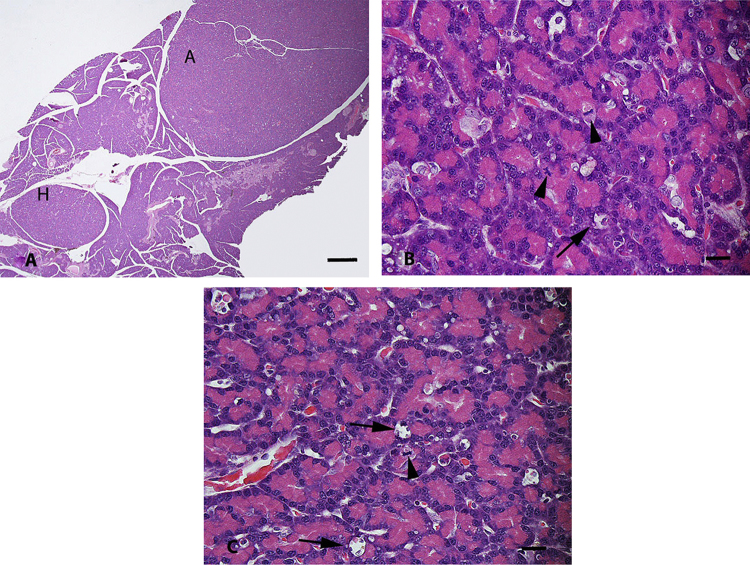

Based on the results of this review of pancreatic tissue from the Butenhoff et al. [4] chronic study (Study 1) conducted in rats with APFO, the test substance produced an increased incidence of pancreatic acinar cell hyperplasia in male rats fed 300 ppm in this study. This review did not identify pancreatic acinar cell adenomas in this study. In partial contrast to these results, Biegel et al. [3] (Study 2) reported increased incidences of acinar cell hyperplasia and adenoma in male rats fed 300 ppm (Fig. 3A–C). The incidences of pancreatic acinar cell hyperplasia reported by Biegel et al. [3] were higher than those observed in this peer review of the study reported by Butenhoff et al. [4].

Fig. 3.

Pancreas from a male rat fed 300 ppm APFO (Study 2). (A) Low magnification of acinar cell hyperplasia (H) and acinar cell adenoma (A). Note that both lesions are round to oval, well-circumscribed and are morphologically similar except for their size. Bar = 500 μm. (B and C) Higher magnification of acinar hyperplasia and adenoma, respectively, from (A). Note that the morphologic similarity of the hyperplasia and adenoma, and the similarity of both to the acinar cell hyperplasia present in Fig. 1B from a control rat (mitoses at arrowheads and apoptosis at arrows). Bars = 20 μm.

An assessment of the significance of the differences between both studies requires consideration of the biological behavior of pancreatic acinar cell hyperplasia and neoplasia, recommended diagnostic criteria for proliferative acinar cell lesions of the rat pancreas and the basis for those criteria, and the potential diagnostic variability between individual pathologists for difficult-to-classify lesions. Proliferative lesions of the acinar pancreas of the rat are thought to exist along a continuum of hyperplasia, adenoma, and carcinoma. However, the likelihood of progression or regression along that continuum is unknown in most cases, and although acinar cell carcinomas are clearly distinguishable morphologically as an entity, typically there are no cytological features that clearly distinguish hyperplasia from adenoma [6], [10]. To achieve some uniformity in diagnoses across laboratories, diagnostic criteria have been established to differentiate acinar cell hyperplasia from adenoma, and the criterion most commonly employed is the somewhat arbitrary feature of two-dimensional size of the lesion [6], [10]. Thus, for many acinar cell proliferations, the difference between the diagnoses of hyperplasia and adenoma reflects a difference in the two-dimensional area of a random section through the lesion rather than known differences in biological potential.

Based on these considerations, it is apparent that the pancreatic effects in both chronic feeding studies in rats with APFO are qualitatively similar, as APFO produced increased incidences of proliferative acinar cell lesions of the pancreas in both studies. The differences observed were only quantitative in nature, that is, more and larger focal proliferative acinar cell lesions were produced in Study 2 as compared to Study 1. Since size (partially dependent on random two-dimensional sectioning through a three-dimensional lesion) is the primary diagnostic criterion distinguishing acinar cell hyperplasia from neoplasia in rodents, the tendency toward larger proliferative lesions accounts for the finding of test-substance related adenomas in Study 2 but not in Study 1.

The reason for this quantitative discordance despite use of the same rat strain and dietary concentration of APFO (300 ppm) in the two studies is not known. However, there are a number of variables that could contribute to the differences observed. Hyperplasia was diagnosed more commonly in the control rats in Study 2, implying a higher background incidence in those rats. Although both studies used CD Sprague Dawley rat stock from Charles River Laboratories (sourced from different breeding facilities), these studies were conducted approximately 10 years apart and in different laboratories. It is expected that these temporal and locational variables were associated with some differences in animal husbandry, including diet, as well as potential genetic drifts within the rat strain over the interim between the conduct of the two studies. During this time, Charles River was experiencing a decrease in longevity in its breeding stock that elicited a change in its breeding program [4]. However, of all possible factors, an undetermined difference in the diets is the most likely factor influencing the different incidences of proliferative acinar cell lesions. Various forms of dietary manipulation, including feeding raw soy diets or diets deficient in choline, are known to moderate the incidences of acinar cell hyperplasia and neoplasia in the pancreas of rodents [11], [12]. For instance, the incidences of acinar cell hyperplasia and adenoma were increased five-fold in control male F344 rats given corn oil by gavage compared to rats not gavaged [10]. Sample source, purity and average daily APFO consumption by 300 ppm group males in both studies were quite similar (14.2 mg/kg in Study 1 and 13.6 mg/kg in Study 2). However, the studies used different base diets. Certified Purina Laboratory Chow (Ralston Purina, Inc., St. Louis, Missouri) was used in Study 1 and Certified Rodent Diet #5002 (PMI Feeds, Inc.) was used in Study 2. Differences in diet composition between these two diets may have influenced the pancreatic acinar cell responses given the known influence of dietary manipulation on proliferative acinar cell lesions in the rat. However, the precise dietary factors that may have been involved are not known. There may be other potential explanations for differences in outcomes between the two studies, but no conclusion can be reached at present.

APFO belongs to a class of compounds known as PPARα agonists. The leading theory for the mechanism of induction of pancreatic acinar cell proliferative lesions by APFO and other PPARα agonists in the rat is based, in a large part, on studies involving the potent PPARα agonist, WY14,643. A proposed mode of action is initiated by PPARα activation in the liver, which alters bile acid composition through enhanced cholesterol/triglyceride excretion and/or causes cholestasis thereby decreasing the total bile acid output [3], [13], [14], [15]. This change in the composition and output of bile triggers increased cholecystokinin (CCK) levels due to enhanced release of CCK from the intestinal mucosa [16], [17]. As CCK has been shown to be a growth factor for rat pancreatic acinar cells via direct binding to acinar CCK1 receptors, this sustained increase in CCK elicits pancreatic acinar hyperplasia, eventually progressing from hyperplasia to neoplasia [3], [18]. This mode of action is unlikely to be relevant to humans, as humans regulate exocrine pancreatic secretion via a neuronal, cholinergic pathway (i.e., indirectly) rather than by direct binding of CCK to pancreatic acinar cell receptors [19], [20], [21]. Human acinar cells do not have functional CCK receptors, nor are they responsive to physiological concentrations of CCK in vitro; whereas CCK1 receptors are plentiful on rat acinar cells and rat acinar cells are responsive to physiological concentrations of CCK in vitro [22], [23], [24], [25], [26]. Further, CCK is a potent stimulator of pancreatic enzyme secretion in the rat. This is in apparent contrast to humans in which in vivo studies with a CCK1R antagonist indicate that CCK is not an essential intermediary of post-prandial pancreatic enzyme secretion [24], [26], [27]. In considering the human relevance of acinar cell hyperplasia and neoplasia in the rodent, it is noteworthy that the histological type of tumor seen in the rodent is distinctly different from tumors of the exocrine pancreas most commonly observed in humans. While rodent tumors typically display acinar differentiation, the majority of human pancreatic neoplasms are of the ductular type [11], [28]. True ductular neoplasms of the pancreas are rare in rats [29]. In addition, while rodent tumors typically have no noticeable effects on the rodent's morbidity or mortality, the majority of human pancreatic neoplasms carry a dismal 5-year survival rate of 6% [30]. Mutation causing activation of the proto-oncogene KRAS occurs in >90% of human pancreatic ductular adenocarcinomas, and this mutation is found in even the earliest precancerous pancreatic lesions in humans [31], [32]. The more advanced neoplastic exocrine pancreatic lesions in humans acquire additional mutations, largely in tumor suppressor genes [31]. PFOA has not shown mutagenic or clastogenic activity in a variety of standard assay systems [33], and is thus unlikely to be a complete carcinogen. In addition, pancreatic acinar cell hyperplasia and neoplasia have been produced in rats by a number of compounds which, like APFO, produce peroxisome proliferation in the liver. These include pharmaceuticals widely used in humans, such as the hypolipidemic agents, clofibrate and nafenopin. There is no known association between these compounds and tumors of the exocrine pancreas in humans. Of particular interest, cancer epidemiology of human populations exposed to PFOA, including occupational exposure, has not found increased risk or incidence of pancreatic cancer to be associated with PFOA exposure [34], [35], [36]. Although the mechanism leading to the formation of proliferative lesions of the acinar pancreas in rats is not well-understood, in the context of human health risk assessment, such lesions are of questionable relevance.

In conclusion, microscopic lesions observed in the exocrine pancreas in a chronic feeding study in rats with APFO were re-evaluated using current diagnostic criteria and involving a pathologist common to both studies. The results of that review were compared to those reported in a second study in the same strain of rat. These reviews were conducted to clarify apparent differences between the two studies relative to compound-related proliferative lesions of the exocrine pancreas. The results of the two studies were similar in that APFO produced proliferative lesions of pancreatic acinar cells in both studies at dietary concentrations of 300 ppm. In the first study, treatment-related changes were limited to increases in acinar cell hyperplasia. In the second study, increased incidences of both hyperplasia and adenoma of acinar cells were observed. Thus, these studies produced qualitatively similar responses in the pancreas, with the differences noted being largely quantitative in nature, that is, higher overall incidences of proliferative lesions and a tendency toward larger areas of proliferation in the second study compared to the earlier study. Although the basis for the quantitative difference observed is not known, since the difference between pancreatic acinar hyperplasia and adenoma in the rat is based primarily on the size of a random section through the lesion, and not necessarily biological potential, the results of the two studies are in reasonable concordance given the experimental variables that exist between them. A number of variables, especially diet, are known to modulate the proliferative response of the acinar pancreas in rats and are likely operative in the differences in degree of response seen in the two chronic studies with APFO. Despite these differences, target organ effects on the pancreas, characterized by focal proliferative lesions of pancreatic acinar cells, were common to both studies. The relevance of this finding to human risk assessment, in the face of differences in the biological behavior of human and rat pancreatic proliferative lesions and the proposed mechanism of formation of these lesions, is questionable.

Source of funding

DuPont Company and 3M Company funded the studies reported herein.

Footnotes

Available online 2 May 2014

Contributor Information

Jessica M. Caverly Rae, Email: Jessica.m.caverly-rae@dupont.com.

Steven R. Frame, Email: steven.r.frame@dupont.com.

Gerald L. Kennedy, Email: Gerald.kennedy@dupont.com.

John L. Butenhoff, Email: jlbutenhoff@mmm.com.

Shu-Ching Chang, Email: s.chang@mmm.com.

References

- 1.Kennedy G.L., Jr., Butenhoff J.L., Olsen G.W., O’Connor J.C., Seacat A.M., Perkins R.G., Biegel L.B., Murphy S.R., Farrar D.G. The toxicology of perfluorooctanoate. Crit. Rev. Toxicol. 2004;34:351–384. doi: 10.1080/10408440490464705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lau C., Anitole K., Hodes C., Lai D., Pfahles-Hutchens A., Seed J. Perfluoroalkyl acids: a review of monitoring and toxicological findings. Toxicol. Sci. 2007;99:366–394. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfm128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Biegel L.B., Hurtt M.E., Frame S.R., O’Connor J.C., Cook J.C. Mechanisms of extrahepatic tumor induction by peroxisome proliferators in male CD rats. Toxicol. Sci. 2001;60:44–55. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/60.1.44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Butenhoff J.L., Kennedy G.L., Jr., Chang S.-C., Olsen G.W. Chronic dietary toxicity and carcinogenicity study with ammonium perfluorooctanoate in Sprague Dawley rats. Toxicology. 2012;298:1–13. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2012.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Klaunig J.E., Babich M.A., Baetcke K.P., Cook J.C., Corton J.C., David R.M., DeLuca J.G., Lai D.Y., McKee R.H., Peters J.M., Roberts R.A., Fenner-Crisp P.A. PPARalpha agonist-induced rodent tumors: modes of action and human relevance. Crit. Rev. Toxicol. 2003;33:655–780. doi: 10.1080/713608372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hansen J.F., Ross P.E., Makovec G.T., Eustis S.L., Sigler R.E. Guides for Toxicologic Pathology. STP/ARP/AFTP; Washington, DC: 1995. Proliferative and other selected lesions of the exocrine pancreas in rats, GI-6. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Giknis M., Clifford C.B. 2004. Compilation of spontaneous neoplastic lesions and survival in Crl:CD (SD) rats from control groups.http://www.criver.com/files/pdfs/rms/cd/rm_rm_r_lesions_survival_crlcd_sd_rats.aspx [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lang P. Charles River; 1987. Spontaneious Neoplastic Lesions in the Crl:CD BR rat. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yokohama Biological reference data on CD(SD)IGS rats. CD9SD. IGS Study Group. http://www.crj.co.jp/cms/pdf/info_common/47/5972776/Biological%20Reference%20Data%20on%20CD(SD)%20Rats%202001.pdf

- 10.Eustis S.L., Boorman G.A. Exocrine pancreas. In: Boorman G.A., Eustis S.L., Elwell M.R., Montgomery C.A. Jr., Mackenzie W.F., editors. Pathology of the Fischer Rat. Academic Press, Inc.; San Diego: 1990. pp. 95–108. (Chapter 8) [Google Scholar]

- 11.Longnecker D.S., Millar P.M. Tumours of the pancreas. In: Turusov V.S.A.M.U., editor. Pathology of Tumors in Laboratory Animals. Volume I – Tumours of the Rat. second ed. International Agency for Research on Cancer; Lyon: 1990. pp. 241–249. [Google Scholar]

- 12.McGuinness E.E., Morgan R.G., Levison D.A., Frape D.L., Hopwood D., Wormsley K.G. The effects of long-term feeding of soya flour on the rat pancreas. Scand. J. Gastroenterol. 1980;15:497–502. doi: 10.3109/00365528009181507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cook J.C., Hurtt M.E., Frame S.R., Biegel L.B. Mechanisms of extrahepatic tumor induction by peroxisome proliferators in Crl:CD BR(CD) rats. Toxicologist. 1994:301. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/60.1.44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liu R.C., Hurtt M.E., Cook J.C., Biegel L.B. Effect of the peroxisome proliferator, ammonium perfluorooctanoate (C8), on hepatic aromatase activity in adult male Crl:CD BR (CD) rats. Fundam. Appl. Toxicol. 1996;30:220–228. doi: 10.1006/faat.1996.0059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Obourn J.D., Frame S.R., Bell R.H., Jr., Longnecker D.S., Elliott G.S., Cook J.C. Mechanisms for the pancreatic oncogenic effects of the peroxisome proliferator Wyeth-14,643. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 1997;145:425–436. doi: 10.1006/taap.1997.8210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cattley R.C., DeLuca J., Elcombe C., Fenner-Crisp P., Lake B.G., Marsman D.S., Pastoor T.A., Popp J.A., Robinson D.E., Schwetz B., Tugwood J., Wahli W. Do peroxisome proliferating compounds pose a hepatocarcinogenic hazard to humans? Regul. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 1998;27:47–60. doi: 10.1006/rtph.1997.1163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gavin C.E., Martin N.P., Schlosser M.J. Absence of specific CCK-A binding sites on human pancreatic membranes. Toxicologist. 1996:334. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Longnecker D.S. Interferences between adaptive and neoplastic growth in the pancreas. Gut. 1985;28:253–258. doi: 10.1136/gut.28.suppl.253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Adler G., Beglinger C., Braun U., Reinshagen M., Koop I., Schafmayer A., Rovati L., Arnold R. Interaction of the cholinergic system and cholecystokinin in the regulation of endogenous and exogenous stimulation of pancreatic secretion in humans. Gastroenterology. 1991;100:537–543. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(91)90227-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Klaunig J.E., Hocevar B.A., Kamendulis L.M. Mode of action analysis of perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA) tumorigenicity and human relevance. Reprod. Toxicol. 2012;33:410–418. doi: 10.1016/j.reprotox.2011.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Soudah H.C., Lu Y., Hasler W.L., Owyang C. Cholecystokinin at physiological levels evokes pancreatic enzyme secretion via a cholinergic pathway. Am. J. Physiol. 1992;263:G102–G107. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1992.263.1.G102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ji B., Bi Y., Simeone D., Mortensen R.M., Logsdon C.D. Human pancreatic acinar cells lack functional responses to cholecystokinin and gastrin. Gastroenterology. 2001;121:1380–1390. doi: 10.1053/gast.2001.29557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Miyasaka K., Shinozaki H., Jimi A., Funakoshi A. Amylase secretion from dispersed human pancreatic acini: neither cholecystokinin a nor cholecystokinin B receptors mediate amylase secretion in vitro. Pancreas. 2002;25:161–165. doi: 10.1097/00006676-200208000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Monstein H.J., Nylander A.G., Salehi A., Chen D., Lundquist I., Hakanson R. Cholecystokinin-A and cholecystokinin-B/gastrin receptor mRNA expression in the gastrointestinal tract and pancreas of the rat and man. A polymerase chain reaction study. Scand. J. Gastroenterol. 1996;31:383–390. doi: 10.3109/00365529609006415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pandiri A.R. Overview of exocrine pancreatic pathobiology. Toxicol. Pathol. 2014;42:207–216. doi: 10.1177/0192623313509907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wank S.A., Pisegna J.R., de Weerth A. Cholecystokinin receptor family. Molecular cloning, structure, and functional expression in rat, guinea pig, and human. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1994;713:49–66. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1994.tb44052.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cantor P., Mortensen P.E., Myhre J., Gjorup I., Worning H., Stahl E., Survill T.T. The effect of the cholecystokinin receptor antagonist MK-329 on meal-stimulated pancreaticobiliary output in humans. Gastroenterology. 1992;102:1742–1751. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(92)91738-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Greaves A.K., Letcher R.J., Sonne C., Dietz R., Born E.W. Tissue-specific concentrations and patterns of perfluoroalkyl carboxylates and sulfonates in East Greenland polar bears. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2012;46:11575–11583. doi: 10.1021/es303400f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Greaves P., Faccini J.M. Rat Histopathology: A Glossary for Use in Toxicity and Carcinogenicity Studies. Elsevier; Amsterdam: 1992. Digestive system. Pancreas. [Google Scholar]

- 30.NCI . Cancer of the Pancreas (National Cancer Institute); 2014. National Institute of Health: Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results Program, 2003–2009.http://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/pancreas.html [Google Scholar]

- 31.Maitra A., Hruban R.H. Pancreatic cancer. Annu. Rev. Pathol. 2008;3:157–188. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pathmechdis.3.121806.154305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Almoguera C., Shibata D., Forrester K., Martin J., Arnheim N., Perucho M. Most human carcinomas of the exocrine pancreas contain mutant c-K-ras genes. Cell. 1988;53:549–554. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(88)90571-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Butenhoff J.L., Kennedy G.L., Jung R., Chang S.C. Evaluation of perfluorooctanoate for potential genotoxicity. Toxicology Reports. 2014;1:252–270. doi: 10.1016/j.toxrep.2014.05.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Barry V., Winquist A., Steenland K. Perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA) exposures and incident cancers among adults living near a chemical plant. Environ. Health Perspect. 2013;121:1313–1318. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1306615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Eriksen K.T., Sorensen M., McLaughlin J.K., Lipworth L., Tjonneland A., Overvad K., Raaschou-Nielsen O. Perfluorooctanoate and perfluorooctanesulfonate plasma levels and risk of cancer in the general Danish population. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2009;101:605–609. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djp041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lundin J.I., Alexander B.H., Olsen G.W., Church T.R. Ammonium perfluorooctanoate production and occupational mortality. Epidemiology. 2009;20:921–928. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0b013e3181b5f395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]