Abstract

Purpose:

The aim of this study is to describe a modified technique of vertically split-conjunctival autograft (CAG) for primary double-head pterygium and evaluate its postoperative outcome.

Methods:

In this retrospective, noncomparative, interventional case series, 87 eyes of 87 patients of double-head pterygium from June 2009 to June 2015 were included. They underwent vertical split CAG. A limbus-limbus orientation was not strictly maintained. Primary outcome measure was recurrence rate. Other outcome measures studied were graft retraction, Tenon's granuloma, dellen, and so on.

Results:

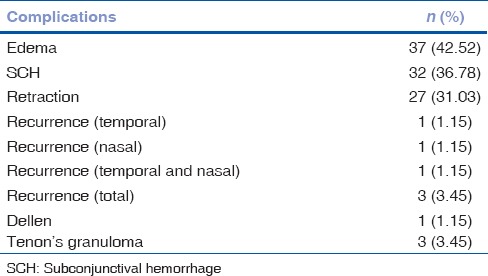

Mean age was 54.54 ± 11.51 years; M:F was 41:46. Mean follow-up was 17.28 ± 10.28 months. The only significant complication was recurrence rate of 3.45% (3 eyes out of 87). Other most common secondary outcome was graft edema, 42.52% (37 eyes out of 87) which resolved without any intervention. Other outcomes such as graft retraction (31.03%), dellen (1.15%), Tenon's granuloma (3.45%), and subconjunctival hemorrhage (36.78%) were recorded.

Conclusion:

Modified vertical split CAG without maintaining limbus-limbus orientation, just large enough to cover the bare scleral defect, appears to be a successful technique with lower recurrence rate in treating double-head pterygium.

Key words: Double-head pterygium, pterygium recurrence, vertical split conjunctiva, without limbus-limbus

A pterygium is an ocular surface fibrovascular, wing-shaped encroachment onto the cornea associated with chronic ultraviolet light exposure.[1,2] Pterygium is seen in all countries of the world but its prevalence is higher in a country like India which is a part of the “pterygium belt.”[3] The main histopathological change in pterygium is elastotic degeneration of conjunctival collagen.[4] Pterygium occurs mostly on the nasal side, which can be attributed to light coming to the temporal cornea and being focused on the nasal cornea.[5] Double-head pterygium, that is, nasal and temporal pterygia in the same eye is rare. In studies by Dolezalová, the incidence was found to be 2.5%.[6] As we know, conjunctival autograft (CAG) is the gold standard in the management of primary pterygium.[7] However, it may not be sufficient to cover the bare scleral defect in a double-head pterygium. Amniotic membrane transplantation (AMT) has been found to be effective in these cases, but it is not easily available to all surgeons and cost is a limiting factor. Superior and inferior bulbar CAG has been effective, but it is difficult to obtain a thin graft from inferior bulbar conjunctiva, so a superior donor site is preferable.

We herein report a novel approach to suturing the vertically split CAG without maintaining limbus-limbus orientation, just large enough to cover the bare scleral defect. We also document the long-term effect on patients with primary double-head pterygium.

Methods

Case records of 87 eyes of 87 patients were included in the study. Data from June 2009 to June 2015 were analyzed retrospectively at a tertiary eye care hospital in South India. All surgeries were performed by one surgeon. Data collected included patient's age, sex, ocular medical and surgical history, visual acuity before and after surgery, surgical technique and complications. Pterygium was graded according to the corneal involvement (Grade 1: crossing limbus; Grade 2: midway between limbus and pupil; Grade 3: reaching up to pupillary margin; and Grade 4: crossing pupillary margin). Up to Grade 3 primary double-head pterygium was included in this study. Grade 4 and recurrent pterygium were excluded from the study. The study protocol adhered to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki. This study was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee.

Surgical procedure

A standard surgical technique similar to Rao et al.[8] was followed with a few modifications [Fig. 1]. 2% Xylocaine (Astra Zeneca, UK) was used as local peribulbar anesthesia. Head of the nasal pterygium was avulsed from the corneal surface using a toothed forceps and an iris spatula. The pterygium body and the underlying fibrovascular tissue was then excised using conjunctival forceps. The corneal and limbal areas were scraped clean of residual tissue with a crescent blade. Gentle wet field cautery was used to achieve hemostasis. A similar procedure was performed for the temporal pterygium. The superior bulbar conjunctiva was selected as the donor site. Balanced salt solution was injected subconjunctivally with 26G needle, which was useful for the good dissection of conjunctiva from Tenon's capsule. A small nick incision was made at the forniceal end using Vannas scissors. A thin conjunctival graft of adequate size was fashioned. Starting from the forniceal end, the graft was split vertically into two halves till the limbus was reached [Fig. 2a]. Tenon's attachment was dissected meticulously for each graft. For successful graft take up, thin graft with meticulous dissection of Tenon's is required.[9] The grafts were excised from their base using Vannas scissor; and without changing the orientation, grafts were placed on bare scleral defect of nasal and temporal sides [Fig. 2b]. Adjunctive agents such as Mitomycin-C (MMC) or 5-fluorouracil were not used in this procedure.[10] With epithelium side up, split CAGs of adequate size just large enough to cover the bare scleral defects were secured with interrupted 10-0 polyamide monofilament sutures (Ethicon, Johnson and Johnson, India). Autografts were secured at the limbus with scleral anchoring sutures superiorly and inferiorly, and the remaining margin of graft was attached to conjunctiva with two or three interrupted sutures. Here, limbus-limbus orientation was not strictly maintained and complete covering of the bare area was ensured. The eye was patched overnight. Postoperatively, topical 0.5% loteprednol etabonate, topical 0.5% moxifloxacin HCl, and tear substitute 0.5% carboxymethyl cellulose were started six times daily for the 1st week and then gradually tapered over 4 weeks. Patients were examined on postoperative day 1 and later asked for follow-up after 1 week, 6 weeks [Fig. 3], 6 months, 1 year [Fig. 4], and every year thereafter. The data from each visit was analyzed and documented. Patients with follow-up of <6 months were not included in the study. Recurrence was defined as fibrovascular tissue in growth of 1.5 mm or more beyond the limbus onto the clear cornea with conjunctival dragging as described by Singh et al.[11]

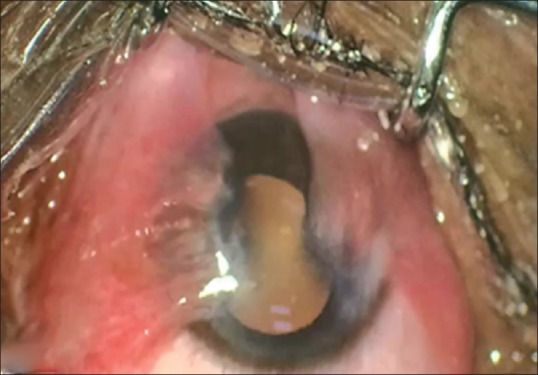

Figure 1.

Double-head pterygium preoperatively

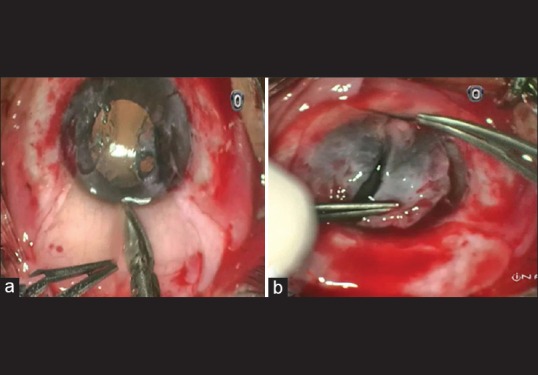

Figure 2.

(a) Vertical split-conjunctival graft technique, (b) split graft in two halves without limbus-limbus orientation

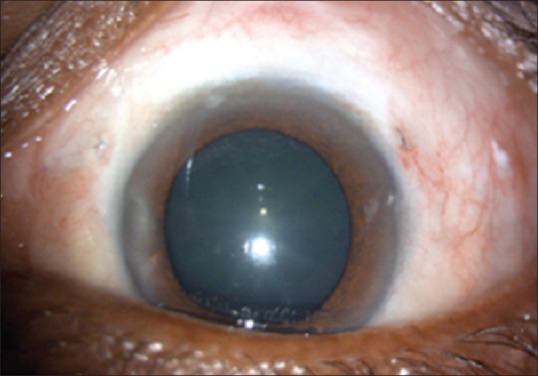

Figure 3.

Six weeks postoperative

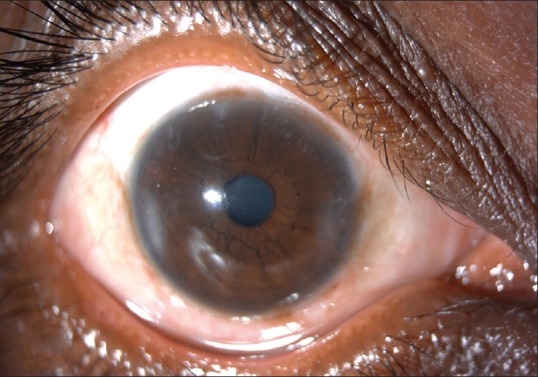

Figure 4.

One-year follow-up

Statistical analysis

Recurrence of pterygium was the primary outcome, whereas Tenon's granuloma, graft retraction, graft edema, subconjunctival hemorrhage, and dellen were considered other outcome variables. Descriptive analysis of all the variables was done using mean and standard deviation for quantitative variables.

Results

On retrospective analysis of 87 eyes with primary double-head pterygium operated by this technique of vertical split CAG without limbus-limbus orientation, the following results were obtained. Mean age was 54.54 ± 11.51 years; M:F was 41:46. Overall, mean follow-up was 17.28 ± 10.28 (months). Patients with follow-up <6 months were not included in the study. Of the total 87 eyes, the left eye constituted 55 eyes and right eye was 32. A total of 3.45% (3 eyes out of 87) had recurrence, of which one had nasal, one temporal, and one nasotemporal. The three eyes in which recurrence occurred due to graft loss might have developed excessive graft retraction in the early postoperative period. Some nonlimbal end loose sutures were removed at follow-up of 1 week. The remaining sutures were removed at 6-week follow-up. Fully 42.52% (37 eyes out of 87) had postoperative edema. Similarly, 36.78% (32 eyes out of 87) had subconjunctival hemorrhage. A total of 31.03% (27 eyes out of 87) had graft retraction in postoperative period, whereas 1.15% (1 eye out of 87) developed dellen and 3.45% (3 eyes out of 87) developed Tenon's granuloma. Table 1 shows the percentage of various outcomes of this study.

Table 1.

Outcomes of this study

Discussion

Pterygium surgery holds the possibility of recurrence as one of the major complications. The operative procedure of choice should aim to minimize the recurrence rate along with better visual cosmetic appearance. In our study, we used vertically split CAG from superior quadrant and secured the graft with sutures without maintaining limbus-limbus orientation on bare scleral defects. Various options available for the management of double-head pterygium are vertical split CAG with limbus-limbus orientation, split CAG with horizontal graft, superior and inferior bulbar CAG, and AMT, but none of them has worldwide acceptance. Conventional bare sclera technique is not done routinely because of high recurrence rate.[12] Various adjunctive therapies have been tried with pterygium excision so as to prevent recurrence. Use of beta irradiation or thiotepa eye drops, antimitotic drugs (MMC and 5-fluorouracil), fibrin glue, and AMT have been used.[13] Various complications of MMC have been noted such as punctuate keratopathy, scleral melt, corneal melting.[14] Amniotic membrane is costly, requires preservation and availability is an issue sometimes. Previous studies have reported higher recurrence rate with AMT compared to conjunctival grafting.[15] Fibrin glue for securing graft gives advantages of easy fixation and better postoperative comfort, but it has high cost and risk of transmission of infectious agents such as parvovirus B19 and prion.[16] Most recently, a new technique named “pterygium extended removal followed by extended conjunctival transplant” for double-head pterygium was published by Hirst and Smallcombe and showed excellent cosmetic results with no recurrence rate in 20 eyes at 1-year follow-up.[17]

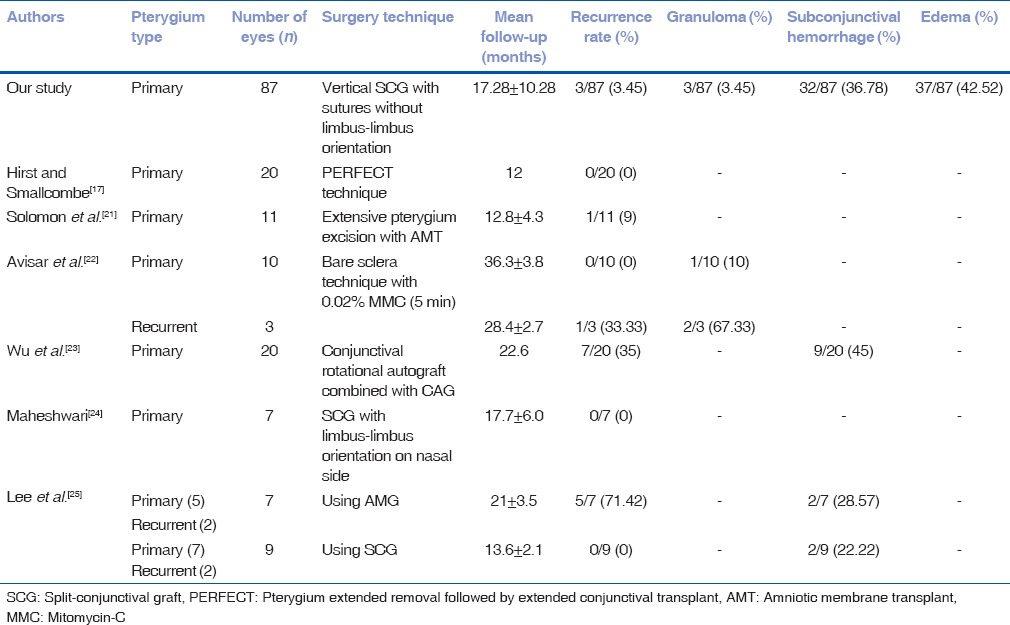

In general, the pterygium recurrence occurs within the first 6 months after surgery.[18] In our study, the overall rate of recurrence was 3.45% (3 eyes out of 87) which was comparable to other published studies. Previous studies mentioned suture-related complications such as infection, prolonged operating time, and postoperative discomfort which can sometimes require second surgery.[19,20] All three eyes which had recurrence might have developed excessive graft retraction due to early loose suture cutting from nonlimbal end at 1-week follow-up, leading to graft loss at 6 weeks, and eventually recurrence at 6-month follow-up. In a study by Solomon et al. with technique of pterygium excision with AMT, the recurrence rate was 9% (1 eye out of 11).[21] Similarly, double-head pterygium excision using bare sclera technique with 0.02% MMC (5 min) was published by Avisar et al. which showed recurrence rate of 0%(0 out of 10 eyes) in primary pterygium and 33.33% (1 eye out of 3) in recurrent double-head pterygium.[22] Using different procedures, previously published studies have shown varying degrees of recurrence that ranged from 0% to 71.42%.[17,21,22,23,24,25] Previous studies reported that, limbal stem cells act as a barrier between the conjunctiva and corneal epithelium and destruction of this barrier leads to growth of conjunctival tissue on to the cornea.[26,27] However, in our study, adequate size graft; enough to cover the bare scleral defect without maintaining limbus-limbus orientation, had still lower recurrence rate comparable to other studies. Graft retraction occurred in 31.03% (27 eyes out of 87) and three eyes had graft loss which resulted in recurrence. The eyes with retraction at 6 weeks resolved without any intervention at subsequent follow-ups. Graft retraction could be due to inclusion of Tenon's in the graft and can be minimized by meticulous dissection of subepithelial graft tissue.[20] Furthermore, suture cutting early in the postoperative period may lead to graft retraction. Graft edema was observed in 42.52% (37 eyes out of 87) which could be due to excessive handling of the graft. Graft edema subsided without any intervention at the end of 1–2 weeks. Graft edema was the most common outcome of our study. Mutlu et al. reported that the most frequent complication in limbal CAG transplantation was graft edema.[28] We had 3.45% (3 eyes out of 87) of Tenon's granuloma, which may be due to inadequate excision of Tenon's tissue from donor bed. Previously published studies advocated this due to friction of the exposed Tenon's tissue with upper lid during blinking eventually leading to granuloma formation.[29,30]

Table 2 shows comparison of different techniques of double-head pterygium surgery and their postoperative outcomes published in previous studies.

Table 2.

Comparison of outcomes with previously published double-head pterygium studies

Conclusion

Our study had certain limitations, being retrospective in nature and nonrandomized. It is probably the first reported surgical technique for primary double-head pterygium of such a large sample size, where limbus-limbus orientation of CAG was not maintained like previous studies; still, the cases had very low recurrence rate. This technique modified with other methods such as use of fibrin glue instead of sutures would definitely reduce postoperative discomfort and irritation with lesser surgical time.

In summary, vertical split conjunctival graft without maintaining limbus-limbus orientation, just large enough to cover the bare scleral defect, appears to be a successful technique with lower recurrence rate in treating double-head pterygium.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Dushku N, Reid TW. Immunohistochemical evidence that human pterygia originate from an invasion of vimentin-expressing altered limbal epithelial basal cells. Curr Eye Res. 1994;13:473–81. doi: 10.3109/02713689408999878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kwok LS, Coroneo MT. A model for pterygium formation. Cornea. 1994;13:219–24. doi: 10.1097/00003226-199405000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Demartini DR, Vastine DW. Pterygium. In: Abbott RL, editor. Surgical Interventions for Corneal and External Diseases. Orlando, USA: Grune and Straton; 1987. p. 141. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Spencer WH. Ophthalmic Pathology: An Atlas and Textbook. 3rd ed. Vol. 1. Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders; 1985. pp. 174–6. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Maloof AJ, Ho A, Coroneo MT. Influence of corneal shape on limbal light focusing. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1994;35:2592–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dolezalová V. Is the occurrence of a temporal pterygium really so rare? Ophthalmologica. 1977;174:88–91. doi: 10.1159/000308583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kenyon KR, Wagoner MD, Hettinger ME. Conjunctival autograft transplantation for advanced and recurrent pterygium. Ophthalmology. 1985;92:1461–70. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(85)33831-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rao SK, Lekha T, Mukesh BN, Sitalakshmi G, Padmanabhan P. Conjunctival-limbal autografts for primary and recurrent pterygia: Technique and results. Indian J Ophthalmol. 1998;46:203–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.de Wit D, Athanasiadis I, Sharma A, Moore J. Sutureless and glue-free conjunctival autograft in pterygium surgery: A case series. Eye (Lond) 2010;24:1474–7. doi: 10.1038/eye.2010.75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kaufman SC, Jacobs DS, Lee WB, Deng SX, Rosenblatt MI, Shtein RM. Options and adjuvants in surgery for pterygium: A report by the American Academy of Ophthalmology. Ophthalmology. 2013;120:201–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2012.06.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Singh G, Wilson MR, Foster CS. Long-term follow-up study of mitomycin eye drops as adjunctive treatment of pterygia and its comparison with conjunctival autograft transplantation. Cornea. 1990;9:331–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fernandes M, Sangwan VS, Bansal AK, Gangopadhyay N, Sridhar MS, Garg P, et al. Outcome of pterygium surgery: Analysis over 14 years. Eye (Lond) 2005;19:1182–90. doi: 10.1038/sj.eye.6701728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kawasaki S, Uno T, Shimamura I, Ohashi Y. Outcome of surgery for recurrent pterygium using intraoperative application of mitomycin C and amniotic membrane transplantation. Jpn J Ophthalmol. 2003;47:625–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Safianik B, Ben-Zion I, Garzozi HJ. Serious corneoscleral complications after pterygium excision with mitomycin C. Br J Ophthalmol. 2002;86:357–8. doi: 10.1136/bjo.86.3.357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Luanratanakorn P, Ratanapakorn T, Suwan-Apichon O, Chuck RS. Randomised controlled study of conjunctival autograft versus amniotic membrane graft in pterygium excision. Br J Ophthalmol. 2006;90:1476–80. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2006.095018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Foroutan A, Beigzadeh F, Ghaempanah MJ, Eshghi P, Amirizadeh N, Sianati H, et al. Efficacy of autologous fibrin glue for primary pterygium surgery with conjunctival autograft. Iran J Ophthalmol. 2011;23:39–47. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hirst LW, Smallcombe K. Double-headed pterygia treated with P.E.R.F.E.C.T for PTERYGIUM. Cornea. 2017;36:98–100. doi: 10.1097/ICO.0000000000001036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Adamis AP, Starck T, Kenyon KR. The management of pterygium. Ophthalmol Clin North Am. 1990;3:611–23. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Allan BD, Short P, Crawford GJ, Barrett GD, Constable IJ. Pterygium excision with conjunctival autografting: An effective and safe technique. Br J Ophthalmol. 1993;77:698–701. doi: 10.1136/bjo.77.11.698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tan D. Conjunctival grafting for ocular surface disease. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 1999;10:277–81. doi: 10.1097/00055735-199908000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Solomon A, Pires RT, Tseng SC. Amniotic membrane transplantation after extensive removal of primary and recurrent pterygia. Ophthalmology. 2001;108:449–60. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(00)00567-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Avisar R, Snir M, Weinberger D. Outcome of double-headed pterygium surgery. Cornea. 2003;22:501–3. doi: 10.1097/00003226-200308000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wu WK, Wong VW, Chi SC, Lam DS. Surgical management of double-head pterygium by using a novel technique: Conjunctival rotational autograft combined with conjunctival autograft. Cornea. 2007;26:1056–9. doi: 10.1097/ICO.0b013e31813349ec. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Maheshwari S. Split-conjunctival grafts for double-head pterygium. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2005;53:53–5. doi: 10.4103/0301-4738.15286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lee BH, Lee GJ, Park YJ, Lee KW. Clinical research on surgical treatment for double-head pterygium. J Korean Ophthalmol Soc. 2010;51:642–50. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tseng SC, Chen JJ, Huan AJ, Kruse FE, Maskin SL, Tsai RJ. Classification of conjunctival surgeries for corneal diseases based on stem cell concept. Ophthalmol Clin North Am. 1990;3:595–610. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pfister RR. Corneal stem cell disease: Concepts, categorization, and treatment by auto- and homotransplantation of limbal stem cells. CLAO J. 1994;20:64–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mutlu FM, Sobaci G, Tatar T, Yildirim E. A comparative study of recurrent pterygium surgery: Limbal conjunctival autograft transplantation versus mitomycin C with conjunctival flap. Ophthalmology. 1999;106:817–21. doi: 10.1016/S0161-6420(99)90172-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vrabec MP, Weisenthal RW, Elsing SH. Subconjunctival fibrosis after conjunctival autograft. Cornea. 1993;12:181–3. doi: 10.1097/00003226-199303000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Starck T, Kenyon KR, Serrano F. Conjunctival autograft for primary and recurrent pterygia: Surgical technique and problem management. Cornea. 1991;10:196–202. doi: 10.1097/00003226-199105000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]