Abstract

Kathleen Holloway and colleagues discuss findings from a rapid assessment of antibiotic use and policies undertaken by South East Asian countries to drive further actions to reduce inappropriate use

Inappropriate use of antibiotics is rampant in South East Asia1 2 3 4 5 6 and is a major contributor to antimicrobial resistance.7 8 9 However, data on antibiotic use are scant, few effective interventions to improve appropriate antibiotic use have been implemented,10 11 and implementation of policies for appropriate use of antibiotics is also poor.12 13 An analysis of secondary data on antibiotic use from 56 low and middle income countries found that countries reporting implementation of more policies also had more appropriate antibiotic use.14 15 Effective policies included having a government health department to promote rational use of medicines, a national strategy to contain antimicrobial resistance, a national drug information centre, drug and therapeutic committees in more than half of all general hospitals and provinces, and undergraduate education on standard treatment guidelines.15 An updated essential medicines list and national formularies were also associated with lower antibiotic use.

Many high level forums have recommended that countries undertake routine monitoring of antibiotic use and use an integrated health systems approach to improve access to and use of medicines, including antibiotics.16 17 18 Most South East Asian countries lack the infrastructure for this, and the responsibility for medicines management is often divided between different government units with no clear accountability. Since 2010, South East Asian countries have been conducting national situational analyses on medicines management every four years,19 supported by the World Health Organization.20 This process involves rapid systematic data collection on use and availability of medicines, including antibiotics, and implementation of policies to ensure appropriate use. A multidisciplinary government team of four to eight people conducts this analysis over two weeks using a predesigned workbook tool. The process ends with a national workshop to identify priorities for action.19

We present key findings from published reports of the situational analyses done during 2010-15 19 and propose next steps to improve antibiotic management.

Methods

We reviewed all the country reports of the situational analyses published on the website of the WHO Regional Office for South-East Asia (WHO/SEARO) 19 and extracted data on antibiotic use in primary care facilities in the public sector, opinions of health workers on antibiotic use, and policies to encourage appropriate use. Box 1 summarises the methods for the country situational analyses. 19

Box 1: Summary of methods for AMR situational analysis

The workbook tool used for the situational analysis built on other tools 21 and was developed by WHO/SEARO in the first round of situational analyses in all 11 countries during 2010-13. The tool was piloted for use by government staff in the second round of analyses in eight countries during 2014-15. The situational analysis approach was developed in the WHO South-East Asian region at the request of member states 20 22 but is suitable for use in other low and middle income countries.

Methods

Over two weeks the analysis team visited all major ministry of health departments and agencies responsible for drug supply, selection, use, regulation, drug policy, insurance, and health professional training to understand what each unit did, and what policies were in place. The team also visited healthcare facilities, with the aim of visiting at least 20 facilities, two of each type of public health facility (primary care centres, secondary, and tertiary hospitals) plus private pharmacies in at least two provinces/regions, as selected by the ministry of health.

Data collection and analysis

Data were collected using a predesigned workbook tool 19 (see supplementary data on bmj.com) by a team of four to eight staff nominated by the government, with at least one team member from each of the government departments responsible for drug supply, selection, use, regulation, and policy. Staff at the central level were interviewed using the open questions in the workbook tool about the health system and policies in place.

At each health facility, the team reviewed 30 primary care outpatient encounters (using documentation available at the facility, such as prescriptions held in the pharmacy or by the patient, paper slips in the pharmacy, patient records, or outpatient registers). The means for standard indicators of medicines use 21 (including the percentage of patients receiving an antibiotic) were calculated for each facility and each category of facility.

Additionally, antibiotic use in 30 cases of upper respiratory tract infection was reviewed, although a lack of records on diagnosis made this difficult in some countries. The percentage of cases with upper respiratory tract infection receiving an antibiotic was calculated for each facility and used to calculate the average for each type of facility. The basis for a diagnosis of upper respiratory tract infection was recorded—for example, runny nose, rhinitis, cough, cold, sore throat, viral acute respiratory infection, acute laryngitis, acute bronchitis, earache, and otitis media.

The availability and procurement prices of essential medicines was also checked.

The team interviewed health workers (including the health facility manager, a prescriber in the outpatient department, the head of the pharmacy, a dispenser, a nurse, and sometimes other staff) using the open questions in the workbook about management of medicines and implementation of policies, and any problems.

Cross-cutting descriptive analysis was done each day and presented by the team at a national workshop at the end of the two weeks. The teams wrote country reports in the workbook tool format, which were published on the WHO/SEARO website after government approval.

WHO facilitated and supervised the entire process, including preparation, data collection and analysis, conducting the national workshop, and writing and publishing the country reports.

All results presented here were taken from the country reports.19 For indicators of antibiotic use, the averages across all facility types are presented. Where possible (in the later second round situation analyses), we calculated the median, and the 25th and 75th centiles for each country. No further statistical analysis could be done because of the small sample sizes and convenience sampling.

For antibiotic management, we focus on policies known to be associated with more appropriate use.15 We present data from all countries to give a regional picture, but we have not made comparisons between countries or over time as the data are insufficient for this purpose.

Findings

National situational analyses were conducted in all 11 countries of the South-East Asia region during 2010-13 and repeated in eight countries during 2014-15. In India, the analysis was done in only two states. In the first round, the data collection tool was being developed by WHO, government staff were less involved, and it was not possible to visit the designated number of health facilities, or collect data on antibiotic use in upper respiratory tract infection in all facilities. In the second round, data collection was done by a full government team using the predesigned workbook tool,19 and it was possible to visit more facilities. The tool was useful for standardised data collection, and it may be further modified based on the experience in countries.

Overall, medicines management is under-resourced in terms of funding and human resources in most countries. Partner support from donors, bilateral and multilateral agencies, and non-governmental agencies is generally limited and fragmented. In most countries, drug management, centrally and at facilities, is done manually leading to poor forecasting, quantification and stock management. Only three of 11 countries reported any monitoring of antibiotic use, either by collecting prescribing data or monitoring antibiotic use in hospitals. Drug regulatory authorities are under-resourced and implementation of drug policies about supply, selection, use, and regulation is suboptimal.19

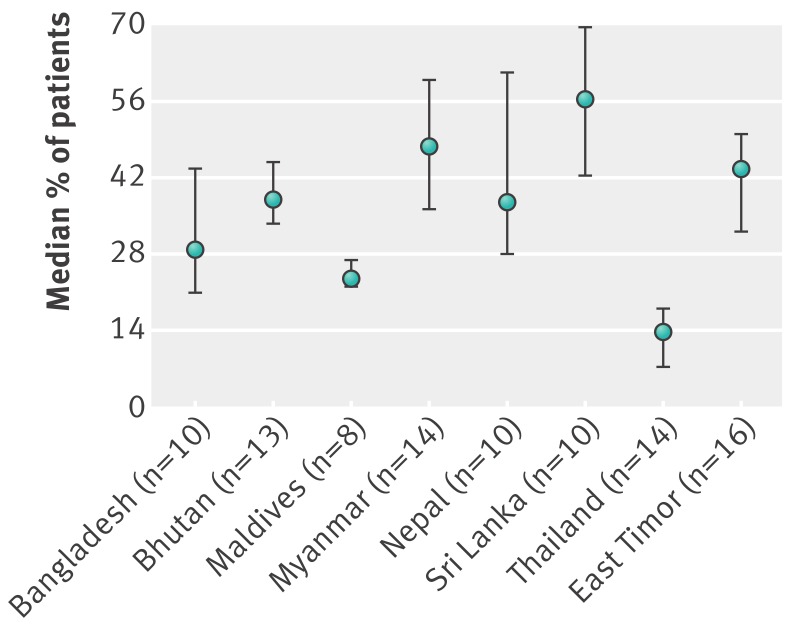

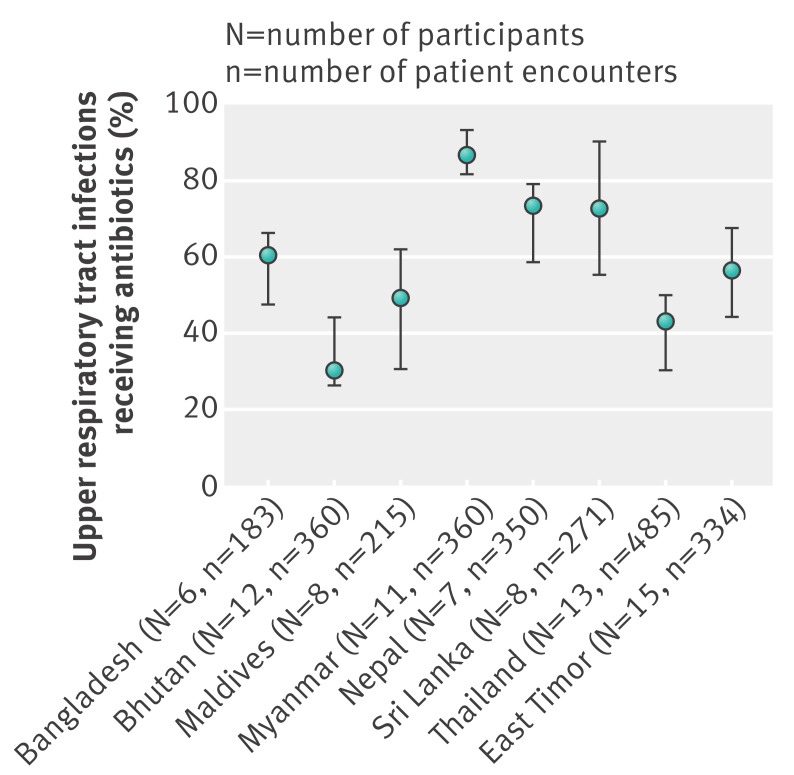

Table 1 summarises antibiotic use in primary care facilities in the public sector, and the presence of policies to promote more appropriate use based on selected indicators from the most recent situational analyses.19 Antibiotic use was high in all countries. Much of it was possibly inappropriate since most cases of upper respiratory tract infection in primary care are viral and do not need an antibiotic.2 4Fig 1 and 2 show the median and centile range of antibiotic use across facilities by country, and also indicate high antibiotic usage. Direct comparison between countries was not possible because the data from the individual surveys were not generalisable, the case mix varied, the capacity of health workers to make accurate diagnoses and their diagnostic terminology varied, and the drugs available were different. However, the lowest antibiotic use for upper respiratory tract infection was in Bhutan and Thailand, both of which had excellent availability of drugs at the facilities.19

Table 1.

Antibiotic use in public sector primary care facilities and presence of selected policies in South East Asian countries

| Country year | No of facilities with antibiotic data (No with URTI data)* | All outpatients | Patients with URTI | National AMR strategy | Nationalor state rational use of medicines unit | Nationalor state drug information centre | DTCs in most hospitals | National or state guidelines updated in past 5 years | Year of latest national or state essential medicines list | Public education on antibiotics in past 2 years | Antibiotics available without prescription | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total No of cases reviewed* | Average % (range) given antibiotics across facility type | Total No of cases reviewed* | Average % (range) given antibiotics across facility type | |||||||||||

| Bangladesh 2014 | 10 (6) | 300 | 31 (19-54) | 183 | 59 (59-60) | No | No | No | No | No | 2008 | No | Yes | |

| Bhutan 2015 | 13 (12) | 390 | 41 (33-49) | 360 | 34 (26-42) | No | Yes, but small | Yes | Referral hospitals only | Yes | 2014 | No | Yes | |

| DPR Korea 2012 | 10 (9) | 300 | 35 (18-51) | 110 | 65 (58-81) | No | No | No | No | Yes | Draft only in 2012 | No | Yes | |

| Rajasthan, India 2013 | 10 (10) | 300 | 62 (53-67) | 198 | 94 (81-100) | No | Yes, in supply unit | No | Yes, but monitor only EML compliance | Yes | 2013 | No | Yes | |

| Karnataka, India 2013 | 13† (6) | 390 | 32† (23-45) | 167 | 70 (64-78) | No | No | Yes | No | No | 2013 | No | Yes | |

| Indonesia 2011 | 8† (3‡) | 240 | 45† (34-55) | 30 | 72‡ | 2011 | Yes, but small | Yes | Yes | Yes | 2008 | Yes, in some provinces | Yes | |

| Maldives 2014 | 8 (8) | 240 | 24 (15-34) | 215 | 43 (34-48) | No | No | No | No | No | 2013, but not followed | No | Yes | |

| Myanmar 2014 | 14 (11) | 420 | 47 (34-54) | 360 | 87 (73-96) | No | No | No | No | Yes | 2010 | No | Yes | |

| Nepal 2014 | 10† (7) | 300 | 44† (39-46) | 350 | 66 (63-71) | 2001 | No | No | Referral hospitals only | No | 2011, but many drugs not supplied | No | Yes | |

| Sri Lanka 2015 | 10 (8) | 300 | 56 (45-67) | 271 | 70 (47-85) | No | No | No | Started in 2015 | No | 2014 | No | Yes | |

| Thailand 2015 | 14 (13) | 420 | 12 (11-14) | 485 | 43 (20-52) | 2011 | No, but has committee | No | Yes | No, but many protocols | 2015 | No, but MOH working group started | Yes | |

| East Timor 2015 | 16 (15) | 480 | 43 (39-50) | 334 | 55 (47-66) | No | No | No | National hospital only | No | 2015, but 2010 version followed | Only in 2016 | Yes | |

AMR=antimicrobial resistance, DTC=drug and therapeutic committee, URTI=upper respiratory tract infection.

*30 patient records were reviewed per health facility from which the % receiving an antibiotic was calculated. 30 cases of URTI were reviewed in health facilities which recorded URTI diagnoses from which the % of URTI cases receiving an antibiotic was calculated19

†Includes private outpatient facilities offering some public sector services: two medical colleges in Karnataka, one medical college in Nepal and one military hospital in Indonesia.

‡Analysis of only 30 prescriptions from three primary care facilities.

Fig 1 Median (25th to 75th centiles) percentage of outpatients prescribed antibiotics across all surveyed public primary care facilities in eight South East Asian countries)

Fig 2 Median (25th to 75th centiles) percentage of patients with upper respiratory tract infection prescribed antibiotics across all surveyed public primary care facilities in eight South East Asian countries

Implementation of recommended policies to reduce inappropriate use of antibiotics14 15 was poor.19 Antibiotics were available over the counter without prescription in all countries, even though this is illegal in all countries except Thailand and East Timor.

Qualitative information on possible causes of inappropriate antibiotic use was collected by interviewing healthcare workers in all countries. Between three and 10 health workers from each of 200 facilities (depending on size) were interviewed. Many health workers were aware that antibiotics were misused and cited various reasons, including patient demand, poor drug supply, and lack of diagnostic facilities, training, appropriate information, and time. Box 2 gives some examples of the views of the health workers taken from the country reports.19

Box 2: Health worker comments relating to inappropriate antibiotic use 19

“How can I make a proper diagnosis in one minute?” (Doctor in Bangladesh)

“According to STGs [standard treatment guidelines] for fever, coughs and colds, we should give paracetamol for a few days and only give antibiotics if there is no response, but I like to give the complete treatment (ie, antibiotics) from the start.” (Doctor in Sri Lanka)

“For children under 5 years with pneumonia I must give amoxicillin according to the IMCI [Integrated Management of Childhood Illness] guidelines. Since we are short of amoxicillin and have short-dated chloramphenicol syrup, I am prescribing chloramphenicol syrup to children of more than 5 years with pneumonia in order to use up the stock.” (Health post in-charge (senior auxiliary health worker who is a paramedical staff of two to three years training) in Nepal)

“We have a lot of soon-to-expire erythromycin so we are pushing it to the dispensary and we will finish it in a few days.” (Pharmacy technician in East Timor)

“I do not like to go to the hospital because of the long wait and the difficulty to see the correct doctor.” (Pharmacy customer in Bhutan)

“We urgently need national standard treatment guidelines to ensure that drugs are used properly and not wasted.” (Senior policy maker in Myanmar)

“We have to give antibiotics like azithromycin and cefixime because the patients have already been prescribed the simpler antibiotics by unqualified practitioners.” (Medical officer in Rajasthan, India)

Antibiotic use was heavily influenced by availability of drugs, staffing policies, and implementation of regulations, as well as the knowledge, beliefs, and qualifications of the health workers. Private pharmacy owners and dispensers in many countries stated that if they did not sell antibiotics without prescription, they would lose business because the patients would simply go elsewhere. These views may not be representative of practice in the entire country or region, but previous studies have reported all these causes.23

The process ended with national workshops to develop recommendations based on the findings with participation from government officials, health workers, and partner organisations. Recommendations were made in all countries 19 to establish and strengthen hospital drug and therapeutic committees; undertake public education on antibiotic use; enforce prescription only availability for newer antibiotics; and establish a government unit with direct responsibility for monitoring use of medicines and coordinating implementation of policies to encourage rational use.

In eight countries where two situational analyses were done, the action taken on the recommendations made in the first situational analysis was assessed. Table 2 summarises antibiotic use in public sector primary care in these eight countries in the first and second analyses, and the measures that were taken to improve appropriate use.

Table 2.

Antibiotic use in public sector primary care facilities and policy changes in eight countries for which a situational analysis was done twice during 2010-1519

| Country | No of public facilities, patient encounters (No with URTI data) | Average % (range) of outpatients given antibiotics across facility type | Average % (range) of patients with URTI given antibiotics across facility type | New policies implemented between 2010-12 and 2014-15 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2010-12 | 2014-15 | 2010-12† | 2014-15† | 2010-12† | 2014-15† | ||||

| Bangladesh | 4, 120 (0) | 10, 300 (6, 183) | 48 (34-74) | 31 (19-54) | — | 59 (59-60) | None. Variable drug availability in terms of supply and type | ||

| Bhutan | 8, 240 (0) | 13, 390 (12, 360) | 33 (31-34) | 41 (33-49) | — | 34 (26-42) | Some monitoring and continuing medical education, updated essential medicines list and standard treatment guidelines, and good drug availability | ||

| Maldives | 5, 150 (0) | 8, 240 (8, 215) | 38 (35-43) | 24 (15-34) | — | 43 (34-48) | None. Decreased drug availability | ||

| Myanmar | 10, 300 (8, 90) | 14, 420 (11, 360) | 38 (27-56) | 47 (34-54) | 83 (72-100) | 87 (73-96) | None. Increased drug availability | ||

| Nepal | 13, 390 (9, 110) | 10, 300 (7, 350) | 47 (21-54) | 44* (39-46) | 73 (72-74) | 66 (63-71) | Non-governmental organisation rational use of medicine project in a few districts. Variable drug availability | ||

| Sri Lanka | 6, 180 (0) | 10,300 (8, 271) | 49 (22-66) | 56 (45-67) | — | 70 (47-85) | Drug and therapeutic committees started in 2015. Variable drug availability | ||

| Thailand | 9, 270 (6, 73) | 14, 420 (13, 485) | 30 (23-45) | 12 (11-14) | 57 (54-62) | 43 (20-52) | Monitoring use, updated essential medicines list, drug and therapeutic committees, and antibiotic smart use and PLEASE projects†¶ | ||

| East Timor | 10, 300 (8, 153) | 16, 480 (15, 334) | 50 (42-75) | 43 (39-50) | 77 (69-88) | 55 (47-66) | None. Decreased drug availability | ||

URTI=upper respiratory tract infection.

*Includes one medical college in Nepal offering some public services.

†Antibiotic smart use project, started in 2007, consists of multifaceted interventions at the individual, organisational, network, and policy levels aimed at changing behaviour, maintaining the changes, and scaling up the project. Activities vary across institutions. ¶PLEASE project, started in 2014 in 71 hospitals. It consists of: pharmacy and therapeutics committee (P), labelling and leaflet (L), essential tools for rational use of medicines (E), awareness of rational use among prescribers and patients (A), special population care (S), and ethics in promotion (E).

Antibiotic use in primary care remained high in all countries, apart from in Thailand where it appeared to have decreased substantially. Thailand was also the only country to report specific nationwide actions to reduce inappropriate antibiotic use.24 These included monitoring use, a project to improve prescribing behaviour25 using multifaceted behaviour change interventions, strengthening hospital drug and therapeutic committees, and regularly updating its essential medicines list. However, the figures should be interpreted with caution. Direct comparison between the two periods is not possible because of the small sample sizes and the selection of different facilities. Furthermore, some countries reported changes in the availability and types of essential medicines which could have affected measurement of antibiotic use between the two periods.

Benefits and limitations of country situational analyses

The situational analyses enabled the rapid collection of data sufficient to show worryingly high use of antibiotics in primary care, and poor implementation of policies to promote more appropriate use.15 Although the data are limited, and not generalisable to the national situation, they have identified serious problems, and provided evidence to advocate for feasible solutions. The data highlight to governments ongoing antibiotic misuse in public primary care, possible reasons for misuse, and the urgent need to implement policies to encourage more appropriate use.19 The analyses have also allowed some monitoring of progress. Since the assessment is completed within two weeks, it is cheap and flexible. Involvement of government staff in data collection helps build their capacity to assess antibiotic use and policy implementation, and increases the likelihood of government follow up. It remains to be seen if greater government involvement guarantees action.

Data collection in the private and hospital sectors was too limited for useful regional analysis. A substantial proportion of antibiotic use occurs in primary care, however, and we expect private sector antibiotic prescribing to be similar to that in the public sector.2 3 The quality of the data may have been affected by time and resource constraints. However, error was minimised by WHO staff supervising all data collection. Furthermore, similar results about antibiotic management in South East Asia have been reported elsewhere.1 2 3 4 5 6 7 10 11 12 13

Developing political will and an enabling environment

The situational analyses would not have been possible without political will. Developing a mandate for action took six years, and involved two regional meetings with experts and senior government officials to finalise the process.26 27 The recommendations of each meeting were incorporated into two WHO regional resolutions adopted by the governments of member states of the South-East Asia region.20 22

Even with a mandate, many government officials feared that they might be blamed for any negative findings, and this may have led to a reluctance to collect and share data on antibiotic management. However, constant reassurance by WHO that the purpose of the situation analyses was not to find fault but to identify weaknesses in the healthcare system, and possible solutions, reduced staff fears, and resulted in free and frank discussions in the national workshops .19

In conclusion, inappropriate use of antibiotics is high, and implementation of policies to encourage more appropriate use is poor in many South-East Asian countries.

We recommend that countries take the following actions:

Undertake regular situational analyses to monitor antibiotic use, and policy implementation as already mandated by WHO member states20

Develop a national coordinating mechanism, and establish a government unit to regularly monitor the use of medicines and antibiotics, and policy implementation

Strengthen hospital drug and therapeutics committees, and update and implement national standard treatment guidelines by training health staff, monitoring the use of medicines, and ensuring that the drug supply matches what is recommended in the guidelines

Invest in public education, and regulate over-the-counter availability of newer antibiotics.

While the member state resolutions have enabled the country situational analyses on medicines management to be done, constant follow up by governments, WHO and partners, and appropriate investment will be needed to make progress.

Key messages

Country situational analyses provide rapid assessment of antibiotic use and policies, particularly where infrastructure for routine monitoring is lacking, so help to build political will and government capacity to take action to improve the appropriate use of antibiotics

South East Asian countries have high antibiotic use, and poor implementation of policies to encourage appropriate use

Measures such as a dedicated government unit for antimicrobial stewardship, a national strategy to contain antimicrobial resistance, updated standard treatment guidelines, hospital drug and therapeutic committees, public education, and restriction of newer antibiotics being available without prescription must be implemented

Web Extra.

Extra material supplied by the author

Workbook tool used for data collection

Contributors and sources:The situational analysis approach described in this article was developed in response to international calls for a systematic, holistic, health systems approach to promote rational use of medicines at the country level. KAH is a public health doctor, who formerly worked as regional adviser in essential drugs and other medicines in the WHO South-East Asia regional office, and as medical officer in charge of promoting rational use of medicines in WHO Geneva. She developed the methods for the situational analyses, facilitated the situational analyses, organised both meetings held in 2010 and 2013, analysed the data, and wrote the manuscript. AK is a professor of pharmacology with international expertise in drug use, medicines pricing and access. She participated in the initial meeting in July 2010, supported three situational analyses during 2015, reviewed the methods, and helped with the analysis and writing the manuscript. GB was a professor and head of pharmacology with international expertise in drug selection and use. She participated in the initial meeting in July 2010, and in the regional consultation in 2013, supported a situational analysis in 2015, reviewed the methods, and helped write the manuscript. MP is a junior public health professional who worked in the WHO South-East Asia regional office. She assisted in data analysis, and developed the graphical presentation. KT is a public health pharmacist who has been working as the regional adviser in essential drugs and other medicines in the WHO Western Pacific, and now in South-East Asia regional office. She participated in the regional consultation in 2013, and assisted in the interpretation of the data, and writing the manuscript.

Competing interests: We have read and understood BMJ policy on declaration of interests, and declare that all five authors were recruited by WHO to facilitate one or more country situational analyses and one or more of the meetings described in the manuscript. KAH is a former regional adviser in essential drugs and other medicines at WHO/SEARO. WHO/SEARO funded all the situational analyses.

Provenance and peer review: Commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

This article is one of a series commissioned by The BMJ based on an idea from WHO SEARO. The BMJ retained full editorial control over external peer review, editing, and publication.

References

- 1.Holloway KA. Promoting the rational use of antibiotics. Regional Health Forum: WHO South East Asia Region 2011;15(1):122−30. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kotwani A, Holloway K. Antibiotic prescribing practice for acute, uncomplicated respiratory tract infections in primary care settings in New Delhi, India. Trop Med Int Health 2014;19:761-8. 10.1111/tmi.12327 pmid:24750565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kotwani A, Chaudhury RR, Holloway K. Antibiotic-prescribing practices of primary care prescribers for acute diarrhea in New Delhi, India. Value Health 2012;15(Suppl):S116-9. 10.1016/j.jval.2011.11.008 pmid:22265057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.World Health Organisation. Medicine use in primary health care in developing and transitional countries: factbook summarising results from studies reported between 1990 and 2006. WHO, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Holloway KA, van Dijk L. The world medicines situation 2011. 3rd ed.. Rational use of medicines World Health Organization, 2011. http://www.who.int/medicines/areas/policy/world_medicines_situation/en/index.html

- 6.Holloway KA. Combating inappropriate use of medicines. Expert Rev Clin Pharmacol 2011;4:335-48. 10.1586/ecp.11.14 pmid:22114780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Holloway KA, Mathai E, Sorensen TL, et al. Community-based surveillance of antimicrobial use and resistance in resource-constrained settings. World Health Organisation, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Livermore DM. Bacterial resistance: origins, epidemiology, and impact. Clin Infect Dis 2003;36(Suppl 1):S11-23. 10.1086/344654 pmid:12516026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Harbarth S, Samore MH. Antimicrobial resistance determinants and future control. Emerg Infect Dis 2005;11:794-801. 10.3201/eid1106.050167 pmid:15963271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Holloway KA, Ivanovska V, Wagner AK, Vialle-Valentin C, Ross-Degnan D. Have we improved use of medicines in developing and transitional countries and do we know how to? Two decades of evidence. Trop Med Int Health 2013;18:656-64. 10.1111/tmi.12123 pmid:23648177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Holloway KA, Ivanovska V, Wagner AK, Vialle-Valentin C, Ross-Degnan D. Prescribing for acute childhood infections in developing and transitional countries, 1990-2009. Paediatr Int Child Health 2015;35:5-13. 10.1179/2046905514Y.0000000115. pmid:24621245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. World Health Organization.Using indicators to measure country pharmaceutical situations: fact book on WHO Level I and Level II monitoring indicators, WHO/TCM/2006.2.WHO, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 13. World Health Organization. Country pharmaceutical situations: Fact Book on WHO Level 1 indicators 2007, WHO/EMP/MPC/2010.1.WHO, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Holloway KA, Henry D. WHO essential medicines policies and use in developing and transitional countries: an analysis of reported policy implementation and medicines use surveys. PLoS Med 2014;11:e1001724 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001724. pmid:25226527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Holloway KA, Rosella L, Henry D. The impact of WHO essential medicines policies on inappropriate use of antibiotics. PLoS One 2016;11:e0152020 10.1371/journal.pone.0152020. pmid:27002977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bigdeli M, Garabedian L, Javadi D, Campbell S. Why a health systems approach? In: Bigdeli M, Peters DH, Wagner AK, eds. Medicines in health systems: advancing access, affordability and appropriate use. WHO and Alliance for Research on Access to Medicines, 2014:18-27. [Google Scholar]

- 17. World Health Organization. WHO Global Strategy for containment of antibiotic resistance.WHO, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 18.World Health Organization. Global action plan on antibiotic resistance. Secretariat’s report A68/20. 2015 http://apps.who.int/gb/ebwha/pdf_files/WHA68/A68_20-en.pdf.

- 19.World Health Organization Regional Office for South-East Asia. Country situation analyses of medicines in health care delivery in South-East Asia. http://www.searo.who.int/entity/medicines/country_situational_analysis/en/

- 20. Resolution of theWHO Regional Committee for South-East Asia. SEA/RC66/R7. Effective management of medicines. 2013. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/128268/1/SEA-RC-66-R7-Effective%20Management%20of%20Medicins.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 21. World Health Organization. WHO Operational package for assessing, monitoring and evaluating country pharmaceutical situations: guide for coordinators and data collectors.WHO, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Resolution of the WHO Regional Committee for South-East Asia. SEA/RC64/R5. Effective National Essential Drug Policy including the rational use of medicines. 2011. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/128366/1/SEA-RC64-R5.pdf

- 23.Radyowijati A, Haak H. Improving antibiotic use in low-income countries: an overview of evidence on determinants. Soc Sci Med 2003;57:733-44. 10.1016/S0277-9536(02)00422-7 pmid:12821020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sumpradit N, Wongkongkathep S, Poonpolsup S, et al. A new chapter in addressing antimicrobial resistance in Thailand. BMJ 2017;358:j2423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sumpradit N, Chongtrakul P, Anuwong K, et al. Antibiotics smart use: a workable model for promoting the rational use of medicines in Thailand. Bull World Health Organ 2012;90:905-13. 10.2471/BLT.12.105445. http://www.who.int/bulletin/volumes/90/12/12-105445.pdf?ua=1. pmid:23284196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.World Health Organization Regional Office for South-East Asia. Promoting rational use of medicines. Report of the intercountry meeting, New Delhi, India, 13–15 July 2010. WHO, 2011.

- 27.World Health Organization Regional Office for South-East Asia. Effective management of medicines. Report of the South-East Asia Regional Consultation. Bangkok, Thailand, 23–26 April 2013. WHO, 2013.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Workbook tool used for data collection