Abstract

Cecilia Stålsby Lundborg and Ashok Tamhankar discuss how antibiotic residues in the environment contribute to antibiotic resistance in South East Asia and propose actions to mitigate the problem

The global action plan on antimicrobial resistance1 emphasises the One Health approach—seeing humans, animals, the food chain, the environment, and the interconnectedness between them as one entity. With growing economic development in South East Asia, the production and use of antibiotics—and therefore also their residues in the environment—are expected to increase.

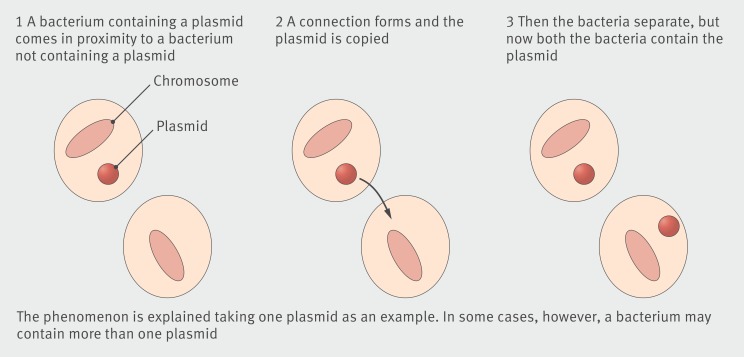

Antibiotic residues in the environment lead to resistant bacteria through selective pressure. Antibiotics like fluoroquinolones (for example, ciprofloxacin) and sulphonamides, (such as sulfamethoxazole) are chemically stable. Their residues are often detected in the environment, and resistance to them is frequently reported.2 3 Beta-lactam antibiotics produce readily degradable residues that are not easily detected but still contribute to resistance.2 3 Theoretically, a chance interaction between a single molecule of an antibiotic and a bacterium can trigger natural selection for resistance, or a mutation favouring resistance. Subsequently, a vertical gene transfer (from one generation to another) or a horizontal gene transfer (transfer of resistance genes from one bacterium to another through a plasmid) may occur (fig 1). Identification of a complete identical sequence of antibiotic resistance genes from soil bacteria and clinical pathogens has demonstrated the potential for horizontal gene transfer between environmental antibiotic resistant bacteria and pathogenic bacteria.2 Humans may be exposed to antibiotic residues or directly to antibiotic resistant bacteria, including pathogens, through food or environment, and potentially be infected. Reduced effectiveness of antibiotics may result in prolonged or poorly controlled infections.

Figure 1 How a plasmid, which might contain antibiotic resistance genes, gets copied from one bacterium to another

In this paper, we identify pathways that contribute to antibiotic residues in the environment and propose priority actions for South East Asian countries to monitor and limit this.

Sources of antibiotic residues in the environment

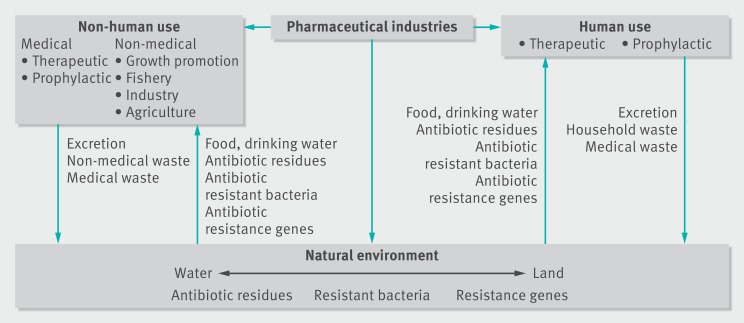

India and Bangladesh are major contributors to global pharmaceutical production.4 Antibiotics are also widely used in South East Asia for therapeutic and non-therapeutic purposes in humans, animals, aquaculture, and agriculture—including use for growth promotion. These activities produce antibiotic residues that contaminate the environment (fig 2). Antibiotics like fluoroquinolones and sulphonamides are chemically stable. Their residues are frequently detected in the environment, and resistance to them is commonly reported.2 3 Beta-lactam antibiotics produce degradable residues that are often not detected but still contribute to resistance.2 3

Figure 2 Potential routes of creation of antibiotic residues in the environment and transmission to and from the environment of antibiotic residues, antibiotic resistant bacteria, and antibiotic resistance genes

Pharmaceutical plants release large amounts of antibiotics into the environment. Antibiotic residues in the effluent (~1500 m3 of wastewater a day) of one cluster of Indian pharmaceutical factories comprising 90 bulk drug manufacturers showed ciprofloxacin concentrations of 28 000 μg/L and 31 000 μg/L on two consecutive days.5 Multiplying these concentrations by the amount of water released each day shows that several kilograms of antibiotics are released daily into the environment, and tons are released every year.5 Antibiotic concentrations measured in lakes close to the cluster showed ciprofloxacin concentration up to 6500 μg/L.6 There are several such clusters in India and Bangladesh.4 Smaller production units also contribute to residues.

From human consumption, conservative estimates suggest that nearly half of consumed antibiotics are released, in active form, through excretion.2 Studies from South East Asia7 8 report residues of several antibiotics in hospital wastewater. However, it should be noted that the majority of antibiotics are used in the community, and this also contributes to environmental residues.

The use of antibiotics in animals contributes equally to residues. Studies from Bangladesh, India, Indonesia, and Thailand have reported antibiotic residues in aquaculture products and aquaculture water. Chloramphenicol was found in fish from Bangladesh,9 and in shrimps from India10 and Indonesia.11 In Thailand, erythromycin and tetracyclines were detected in aquaculture water with oxytetracycline concentrations up to 180 ng/L.12 In integrated aquaculture farms excreta from chickens, that may have been given antibiotics, is used as feed. This can lead to the transfer of residues to fish used for human consumption.13

Risks with antibiotic residues in the environment

Wastewater from hospitals, livestock and poultry farms, aquaculture farms, and human dwellings is sometimes released, without any treatment, into the environment. Even if it goes to municipal sewage treatment plants, their antibiotic removal capacity is not adequate14 and this water may end up in drinking water sources like rivers and lakes. Many countries do not have routine monitoring of pharmaceuticals, including antibiotics, in drinking water because of the associated high costs.15

A study from Thailand reported levels of ciprofloxacin up to 200 ng/L in wastewater treatment plants and receiving waters.16 A study from five tropical Asian countries found predominance of sulfonamides in rivers and coastal waters, and it was estimated that about 12 tons of sulfamethoxazole per year was released into the sea.12

When untreated or inadequately treated wastewater containing antibiotics is released into water bodies, antibiotics and their metabolites can enter the food chain. Persistence, bioaccumulation, and toxicity may vary between different antibiotics, but all contribute to resistance and have adverse effects on living organisms. Laboratory experiments mimicking the concentration of pharmaceutical plant effluent in India with antibiotics at the lowest tested effluent concentration (0.2%) showed a 40% reduction in the growth of exposed tadpoles.17 A risk assessment in India using urban wastewater showed trimethoprim toxicity to bacteria, duckweed, algae, daphnia, rotifers, and fish in bioassays.18 Antibiotics have also been shown to accumulate in plant parts like leaves, stem, and roots.19

Present situation of wastewater remediation

Sewage or wastewater treatment plants help remove antibiotics from wastewater to varying degrees. However, antibiotics have been found in effluent from treatment plants even in high income countries, indicating that current technology does not completely eliminate antibiotics.2 3 15 20 The situation is worse in South East Asia as up to 80% of the wastewater is not treated at all and contaminates ground water, surface waters, soil, and even crops.14

In Thailand up to 3 μg/L of oxytetracycline and up to 1.6 μg/L of enrofloxacin were detected in conventional treatment plant effluent.21 Advanced treatments with chlorination and ultraviolet radiation can increase the removal efficiency by up to 50-90%.15 16 However, another study from Thailand showed residues for roxithromycin, sulfamethazine, and sulfamethoxazole even with advanced treatment.8 Effluent from a treatment plant serving drug manufacturers in India contained up to 31 000 μg/L of ciprofloxacin.5 Ampicillin up to 21 μg/L was detected in effluent from a treatment plant serving community wastewater in an Indian city.22

Laboratory experiments show that very low antibiotic concentrations, similar to those in the environment, can select for and maintain resistance.23 It is uncertain if antibiotics can be totally eliminated from wastewaters or maintained at levels below the risk for development of resistance. Therefore, predicted no effect environmental concentrations (PNEC) for resistance selection have been postulated for some antibiotics—for example, ciprofloxacin 64 pg/mL, azithromycin 250 pg/mL, meropenem 64 pg/mL, oxytetracycline 500 pg/mL, sulfamethoxazole 16 ng/mL, and colistin 2 ng/mL.24 These concentrations serve as a guideline in setting up environmental monitoring programmes and for interventions to keep environmental antibiotic concentrations below a certain limit.

Recommendations to reduce antibiotic residues

The global action plan on antimicrobial resistance encourages interventions and policies to protect human health, and the environment as a whole, in the face of uncertain risks.25 Solutions to reduce antibiotic residues in the environment are crucial to reduce development of resistance, and must be integrated within existing national programmes.

Increase awareness about antibiotic residues and optimise antibiotic use

The World Health Organization, South-East Asia Regional Office (WHO SEARO) has recently undertaken initiatives to map information on environmental antibiotic residues in the region and is planning activities to spread awareness. Education and training of all stakeholders—the public, health professionals, manufacturers, and policy makers—on the origin of residues and the associated risks is essential. This training must focus on the whole chain from production, prescribing, and use, to the importance of wastewater management and correct disposal of unused drugs.

Awareness of rational use of antibiotics in humans and animals is important. Infection prevention and control measures can also help reduce the overall use of antibiotics. Take-back programmes involving return of unused or excess drugs to pharmacies is recommended by WHO,15 though such initiatives have not yet been tried at scale in South East Asia.

Wastewater treatment plants to keep residues entering the environment to a minimum

The number of wastewater treatment plants in the region is indequate.14 Considering resource limitations, decentralised, on site treatment plants equipped to neutralise antibiotics and resistant bacteria (OSTP-Zero ARB) must be considered.26 These can provide an efficient, and low cost solution at the point of origin, such as pharmaceutical industries, hospitals, agriculture and aquaculture, and in the community.14 Public-private partnerships and industry incentives to establish such treatment plants may accelerate progress.

Septic tanks are beneficial as human waste is collected, but these might also serve as storehouses of antibiotics and breeding grounds for resistant bacteria. The contents must not be released untreated into the environment when the tanks are emptied.14 Small size OSTP- Zero ARB can be a solution for these as well.

Monitoring, research, and innovation

It is estimated that many tons of antibiotic residues are released into the environment in South East Asia every year. Yet there is lack of documentation of antibiotic residues in wastewaters from hospital, industry, treatment plant effluents, aquaculture, and drinking water sources. Routine surveillance of environmental antibiotic concentrations and resistant bacteria can guide the development and implementation of contextually appropriate interventions.

Innovative, affordable, and easy to use methods for detecting antibiotic residues and resistant bacteria are needed. The tools that are currently available, such as high performance liquid chromatography coupled with tandem mass spectrometry, are expensive for routine monitoring. Qualitative information such as the presence of an antibiotic or antibiotic mixture above a certain limit of detection would also be adequate if methods for detecting precise concentrations are costly.

In addition, implementation research can help evaluate adoption of interventions such as take back programmes for the management of leftover antibiotics. Mathematical modelling based on antibiotic use can potentially be used to quantify residues and their influence on resistance. Qualitative studies among key stakeholders including the community, industries, and policy makers are essential to understand how they perceive the problem and to develop feasible solutions.

Innovations should target efficient and affordable technology to remove antibiotic residues and resistant bacteria, preferably at the point of origin. Technology to recover and, where possible, reuse antibiotics and pharmaceutical molecules is an area of research.

Photocatalysis—use of a substance to accelerate a process of a chemical reaction in the presence of light, such as solar or ultraviolet radiation or light emitting diode—holds promise for disinfection of bacteria and decontamination of antibiotics.27

Need for regulation

WHO has called for policies to improve the management of pharmaceutical waste and minimise residues entering the environment.15 Specific regulations are, however, limited by a lack of consensus on safe environmental concentrations of antibiotic residues from the perspective of development of resistance.24

Environmental risk assessments to study interactions of agents or hazards, humans and ecological resources are required for launching new medicines in Europe and the US, but not for medicines already on the market.28 These requirements don’t address resistance implications, but focus on ecological toxicity to various species.28 Ecopharmacovigilance is a relatively new concept to track the environmental risks of drugs and involves detection, assessment, and prevention of adverse effects to humans or other species. This is gaining interest in Europe and also in India as it exports medicines to many countries across the globe.28 29

Sustainable development goal 12.4 states that by 2020 countries must “achieve the environmentally sound management of chemicals and all wastes throughout their life cycle, in accordance with agreed international frameworks, and significantly reduce their release to air, water, and soil in order to minimise their adverse impacts on human health and the environment.”30 Pharmaceuticals must be addressed within this target. The sustainable development goals serve as a framework together with global1 and national action plans for regulation on release of antibiotic residues.

Key messages

Antibiotic manufacture, as well as its use, contributes to antibiotic residues in the environment, which leads to development of resistant bacteria

In South East Asia, wastewater containing antibiotics is often directly released into the environment without sufficient treatment

Research must focus on developing efficient, affordable, small scale treatment plants to eliminate antibiotic residues and resistant bacteria at the point of origin, and tools to monitor their levels in the environment

Contributors and sources: Both authors are working together on projects on antibiotic residues and antibiotic resistance in the environment in India and Vietnam. CSL is professor and research group leader and has been principal investigator in several research projects on a wide range of aspects concerning antibiotics, in many of which AJT has been involved. CSL has been course leader for several international courses on antimicrobial resistance, to which AJT has contributed. CSL was scientific adviser to the Swedish Research Council on development research and also to ReAct—Action on Antibiotic Resistance. She has been working with Strama, Swedish Strategic Programme for the Rational Use of Antimicrobial Agents and Surveillance of Resistance for 15 years. AJT, a former senior scientist with Bio-Medical group of BARC, India, is founder member and national coordinator of Indian Initiative for Management of Antibiotic Resistance. Both authors contributed equally to the article, which is based on a report submitted to the WHO SEARO by them. Both are guarantors.

Competing interests: We have read and understood BMJ’s policy on declaration of interest and have no relevant interests to declare. This work was commissioned by the WHO Regional Office of South East Asia using the UK government’s Fleming Fund. The authors alone are responsible for the views expressed in this article, which does not necessarily represent the views, decisions, or policies of the institutions with which the authors are affiliated.

Provenance and peer review: Commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

This article is one of a series commissioned by The BMJ based on an idea from WHO SEARO. The BMJ retained full editorial control over external peer review, editing, and publication.

References

- 1.World Health Organization. Global action plan on antimicrobial resistance. 2015. www.wpro.who.int/entity/drug_resistance/resources/global_action_plan_eng.pdf. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Ashbolt NJ, Amézquita A, Backhaus T, et al. Human Health Risk Assessment (HHRA) for environmental development and transfer of antibiotic resistance. Environ Health Perspect 2013;121:993-1001.pmid:23838256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kümmerer K. Antibiotics in the aquatic environment: a review: part I. Chemosphere 2009;75:417-34. 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2008.11.086 pmid:19185900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rehman MS, Rashid N, Ashfaq M, Saif A, Ahmad N, Han JI. Global risk of pharmaceutical contamination from highly populated developing countries. Chemosphere 2015;138:1045-55. 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2013.02.036 pmid:23535471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Larsson DGJ, de Pedro C, Paxeus N. Effluent from drug manufactures contains extremely high levels of pharmaceuticals. J Hazard Mater 2007;148:751-5. 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2007.07.008 pmid:17706342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fick J, Söderström H, Lindberg RH, Phan C, Tysklind M, Larsson DGJ. Contamination of surface, ground, and drinking water from pharmaceutical production. Environ Toxicol Chem 2009;28:2522-7. 10.1897/09-073.1 pmid:19449981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Diwan V, Tamhankar AJ, Khandal RK, et al. Antibiotics and antibiotic resistant bacteria in waters associated with a hospital in Ujjain, India. BMC Public Health 2010;10:414 10.1186/1471-2458-10-414 pmid:20626873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sinthuchai D, Boontanon SK, Boontanon N, Polprasert C. Evaluation of removal efficiency of human antibiotics in wastewater treatment plants in Bangkok, Thailand. Water Sci Technol 2016;73:182-91. 10.2166/wst.2015.484 pmid:26744950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bakar MA, Morshed AJM, Islam F, Karim R. Screening of chloramphenicol residues in chickens and fish in Chittagong city of Bangladesh. Bangl J Vet Med 2013;11:173-5. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Swapna KM, Rajesh R, Lakshmanan PT. Incidence of antibiotic residues in farmed shrimps from the southern states of India. Indian Journal of Geo-Marine Sciences 2012;41:344-7. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Impens S, Reybroeck W, Vercammen J, et al. Screening and confirmation of chloramphenicol in shrimp tissue using ELISA in combination with GC-MS2 and LC-MS2 Anal Chim Acta 2003;483:153-63 10.1016/S0003-2670(02)01232-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shimizu A, Takada H, Koike T, et al. Ubiquitous occurrence of sulfonamides in tropical Asian waters. Sci Total Environ 2013;452-453:108-15. 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2013.02.027 pmid:23500404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Koeypudsa W, Yakupitiyage A, Tangtrongpiros J. The fate of chlortetracycline residues in a simulated chicken-fish integrated farming systems. Aquacult Res 2005;36:570-7 10.1111/j.1365-2109.2005.01255.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.WEPA Outlook on Environmental management in Asia. www.wepa-db.net/pdf/1203outlook/01.pdf.

- 15.World Health Organization. Pharmaceticals in drinking water. 2012. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/44630/1/9789241502085_eng.pdf.

- 16.Tewari S, Jindal R, Kho YL, Eo S, Choi K. Major pharmaceutical residues in wastewater treatment plants and receiving waters in Bangkok, Thailand, and associated ecological risks. Chemosphere 2013;91:697-704. 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2012.12.042 pmid:23332673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Carlsson G, Orn S, Larsson DG. Effluent from bulk drug production is toxic to aquatic vertebrates. Environ Toxicol Chem 2009;28:2656-62. 10.1897/08-524.1 pmid:19186889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Singh KP, Rai P, Singh AK, Verma P, Gupta S. Occurrence of pharmaceuticals in urban wastewater of north Indian cities and risk assessment. Environ Monit Assess 2014;186:6663-82. 10.1007/s10661-014-3881-8 pmid:25004851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hu X, Zhou Q, Luo Y. Occurrence and source analysis of typical veterinary antibiotics in manure, soil, vegetables and groundwater from organic vegetable bases, northern China. Environ Pollut 2010;158:2992-8. 10.1016/j.envpol.2010.05.023 pmid:20580472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Watkinson AJ, Murby EJ, Kolpin DW, Costanzo SD. The occurrence of antibiotics in an urban watershed: from wastewater to drinking water. Sci Total Environ 2009;407:2711-23. 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2008.11.059 pmid:19138787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rico A, Oliveira R, McDonough S, et al. Use, fate and ecological risks of antibiotics applied in tilapia cage farming in Thailand. Environ Pollut 2014;191:8-16. 10.1016/j.envpol.2014.04.002 pmid:24780637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mutiyar PK, Mittal AK. Occurrences and fate of selected human antibiotics in influents and effluents of sewage treatment plant and effluent-receiving river Yamuna in Delhi (India). Environ Monit Assess 2014;186:541-57. 10.1007/s10661-013-3398-6 pmid:24085621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gullberg E, Cao S, Berg OG, et al. Selection of resistant bacteria at very low antibiotic concentrations. PLoS Pathog 2011;7:e1002158 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002158 pmid:21811410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bengtsson-Palme J, Larsson DGJ. Concentrations of antibiotics predicted to select for resistant bacteria: Proposed limits for environmental regulation. Environ Int 2016;86:140-9. 10.1016/j.envint.2015.10.015 pmid:26590482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kriebel D, Tickner J, Epstein P, et al. The precautionary principle in environmental science. Environ Health Perspect 2001;109:871-6. 10.1289/ehp.01109871 pmid:11673114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tamhankar AJ. Location specific integrated antibiotic resistance management strategy (LIARMS). In: Ragunath D, Nagaraja V, Durga Rao C, eds. Antimicrobial resistance: the modern epidemic.Macmillan: 390-9. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Das S, Sinha S, Das B, et al. Disinfection of multidrug resistant escherichia coli by solar photocatalysis using Fe-doped ZnO nanoparticles. Sci Rep 2017;7:104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Holm G, Snape JR, Murray-Smith R, Talbot J, Taylor D, Sörme P. Implementing ecopharmacovigilance in practice: challenges and potential opportunities. Drug Saf 2013;36:533-46. 10.1007/s40264-013-0049-3 pmid:23620169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Revannasiddaiah N, Kumar CA. India’s progress towards ecopharmacovigiliance. J Drug Discovery and Therapeutics 2015;3:62-8. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sustaniable Development Goals. Knowledge platform. https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org.