Abstract

Sirenda Vong and colleagues argue that investing in information technology surveillance systems to detect trends is an essential first step in tackling antimicrobial resistance in South East Asian countries

Key messages

Lack of information technology (IT) infrastructure is often cited as a barrier to comprehensive antimicrobial resistance (AMR) surveillance and antibiotic usage stewardship programmes in low and middle income countries

Few open access software options that might support an IT infrastructure for AMR surveillance are available

IT systems should support regular communication between central and local levels to enable feedback, improved data quality, and acceptance by users

Good data quality in an IT system requires data validation to be carried out in collaboration with the laboratories to correct inconsistencies and errors

The World Health Organization, South East Asia regional office will support international partners to translate the present recommendations into actions and mobilise resources and leverage partnerships

The continual rise of antimicrobial resistance (AMR) was recognised by the United Nations in 2016 as a serious threat to global health and human development.1 Surveillance of AMR and monitoring antibiotic usage are complementary and fundamental to everyday clinical practice. They are also central to monitoring the effectiveness of national AMR prevention and containment programmes. The extent of AMR (eg, prevalence and trends, public health significance of resistance phenotypes or species) can be determined through quality laboratories interconnected in a well organised national surveillance network.2 Building this surveillance network remains a challenge in most countries, including those of the World Health Organization’s (WHO) South East Asia region (SEAR). A lack of information technology (IT) infrastructure is often cited as a barrier to comprehensive AMR surveillance and antibiotic usage programmes.3 Surveillance of AMR and antibiotic usage is complex as data generated from one single patient require analysis of several organisms. These must be tested for susceptibility to several antibiotics and combined with antibiotic treatment regimens. When surveillance data are captured by networks of clinical laboratories, only IT systems can readily manage and consolidate the information to allow timely and thorough analyses nationally and locally. Computers can be used efficiently to study the emergence of resistant genes and in systems to detect an outbreak within a hospital or nationally; for analysis of AMR clusters through antibiotic resistance profiles; for automated or manual entry of data for web based reporting that allows real time integration and timely analysis; and to provide automated reporting with the ability for space-time visualisation.

Surveillance specialists in the region understand the potential benefits of automation offered through software, hardware, and communication infrastructure, although ways to set up an IT system are unclear. Major barriers to improving the quality of work are the costs of software and hardware, of maintaining systems, and of employing staff. Inadequate infrastructure also leads to limited/slow internet connectivity.

We present here strategic directions and practical solutions for setting up an IT system to improve the AMR surveillance network for countries in the South East Asia region—developing their full participation in the Global AMR Surveillance System (GLASS).4

Methods

This paper is based on literature and desk review, and discussions among a group of IT experts, epidemiologists, and microbiologists who were convened by WHO SEARO in September 2016 in New Delhi, India. The group reviewed ways in which IT might improve AMR surveillance in SEAR countries. The discussion proposed a roadmap to generate local and national surveillance of AMR trends in human health using IT in the first instance. It acknowledged the importance of good quality laboratory data, their representativeness and antibiotic resistance in other contexts, such as AMR surveillance in animals and surveillance of antibiotic usage in both humans and animals used for food.

SEAR is the WHO region with the smallest number of countries (n=11) but accounts for 26% of the global population.4 The region is composed of low and middle income countries, including Thailand and Maldives as the only two upper middle income countries.5

Constraints of IT surveillance in South East Asia

Expansion of the internet and IT across Asia has been unprecedented, but the use of IT surveillance for AMR is limited. Surveillance of antibiotic resistant bacteria is sporadic and selective in most SEAR countries. When conducted, it is typically in laboratories of large universities and private hospitals that are not linked within a national network. In 2014, five of the 11 SEAR countries (India, Bangladesh, Indonesia, Maldives, and East Timor) could not generate national AMR data, and only Thailand and Nepal have the capacity to collect and collate data from more than five laboratory sites.6 A recent review suggested that of 110 articles published in the past 16 years about computer based surveillance of infectious diseases, only five (5%) stem from SEAR, including one on computed AMR surveillance, which presented the use of WHONET (Rattanaumpawan P, personal communication).7

In countries with a national database, data from hospital laboratory sites are often collated in Microsoft Excel format and sent to the database irregularly by email or as hard copies. The laboratory data received often have inconsistent variables and variable file formats, leading to errors when data are manually re-entered, recoded, and reformatted. Such a process is labour intensive, and thus no such systems have successfully provided an early warning system. Combining clinical data, pharmacy data, and microbiology data remains a challenge. Thailand with its national AMR surveillance network of >60 sentinel hospital laboratories (Thamlikitkul V, personal communication), and India with its newly implemented national network of 10 laboratories, are no exception to these problems (Gupta S, personal communication). The Indian Council of Medical Research has started to introduce an open source, web based, real time AMR data collection system (Walia K, personal communication).

Other barriers include technical problems (eg, configuration of WHONET and BacLink7 8), system interoperability, lack of data standards, and lack of a well trained local and national IT workforce to advise and lead the process. Ten of 11 SEAR countries have limited human resources with which to process the analysis and generate standardised reports and feedback.

IT based AMR surveillance: examples from Sweden and Japan

AMR surveillance in Sweden was strengthened in 2012 by the setting up of Svebar—a national automated system for collecting culture and antibiotic susceptibility testing results from Swedish clinical laboratories.9 10

The system, owned by the Public Health Agency of Sweden (PHAS), creates real time early warnings of highly significant AMR (eg, multiresistant and extremely resistant microbes) and has a database of identified micro-organisms and all antimicrobial susceptibility testing results from participating laboratories. Early warning reports are automatically generated and immediately returned to the individual laboratory. The reports are based on “triggers” where the circumstances for an early warning signal are defined. Two typical examples of “triggers” are K pneumoniae resistant to carbapenem and E coli resistant to colistin in any clinical sample. The database, on the other hand, owned by the participating laboratories, is used for studying longitudinal and geographical trends in AMR.

Svebar generates standardised local and national reports, producing tables of aggregated resistance data for each species and antibiotic.

To achieve good data quality in an IT system, a data validation process is required that harmonises nomenclature and routines, and collaboration with the laboratories to correct inconsistencies and errors. Common antibiotic susceptibility testing standards—for example, the European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (EUCAST), a scientific committee that is to validate reference phenotypic and genotypic methods for antimicrobial susceptibility testing are also valuable when comparing data from different sources. Further harmonisation of Swedish data is underway through the European Antimicrobial Resistance Surveillance Network (EARS-Net) and GLASS.4 11

Although joining Svebar is voluntary, the system has enrolled most of the country’s clinical microbiology laboratories. PHAS experts report that continuous discussion between PHAS and the laboratories explains this high participation. For example, a user conference is held yearly at PHAS, where laboratory representatives are invited to discuss all aspects of the system—from generated reports and early warnings to quality of the underlying data. High public and professional awareness about AMR has also facilitated political commitment and paved the way for introduction of the system (Kahlmeter G, Aspevall O, Söderblom T, personal communication). In the future Svebar aims to incorporate whole genome sequencing data in AMR surveillance; and integrate antibiotic consumption and veterinary surveillance data to enable further analysis for policy making.

Japan Nosocomial Infections Surveillance (JANIS) is an automated programme that centralises AMR related hospital data to be compiled, analysed, and published periodically. Confidential summary reports are also shared with each participating hospital, comparing its data with that of the group of participating hospitals. Japan has reached out to many countries in the region (eg, Indonesia and India) by offering the JANIS software to support national AMR surveillance.12 13 14

Requirements, options, and proposed solutions

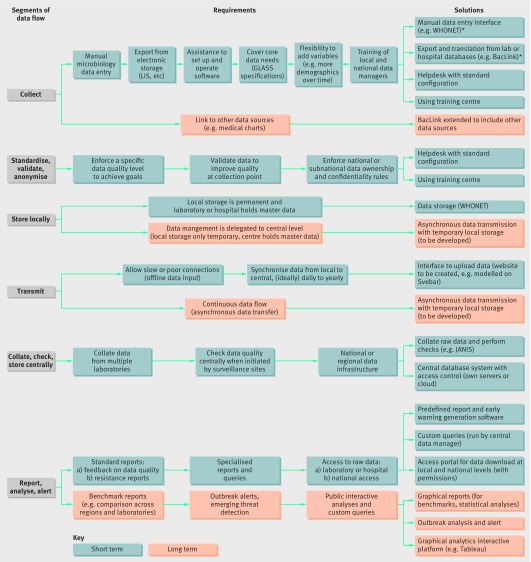

The requirements for an IT system to support the data flow from hospitals or laboratory sites to a national centre to generate national data and analyses can be broken down into six segments of data flow: collect; standardise, validate, and anonymise; store locally; transmit; collate, check, and store centrally; report, analyse, and alert (fig 1). For SEAR, improving the data collection process and the technical capacity at a national data centre also increases data quality and the ability to assess and improve through feedback the reliability of testing by participating laboratories.

Fig 1 Requirements and proposed solution by segment of surveillance data flow. *WHONET is free windows based database software developed for the management and analysis of microbiology laboratory data with a special focus on the analysis of antimicrobial susceptibility test results. BacLink is a free data conversion utility to facilitate the transfer of data from existing laboratory information systems into WHONET and thus avoid the need for double data entry. WHONET and BacLink are developed by the WHO Collaborating Centre for Surveillance of Antimicrobial Resistance based at the Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston. LIS=laboratory information system; GLASS=Global AMR Surveillance System; JANIS=Japan Nosocomial Infections Surveillance; Svebar=Swedish surveillance of antimicrobial resistance.

Firstly, data completeness and accuracy should be improved by enhanced data collection directly from the testing instruments into a laboratory results database or laboratory information system, while allowing more advanced laboratory sites to set up microbiology data transfer from their existing information system or hospital management system; by providing technical assistance for sites at each step of the data collection process to supplement limited availability and skills; and allowing offline data entry and synchronization with a central location with varying frequency, implying the need to store data locally at the laboratory and hospital, which would hold the master copy of the data.

Secondly, it is crucial to build up skills and IT capacity to collate and check data in a central location, and run analyses, reports, and alerts on the whole dataset centrally to organise skills and resources based on mutual principles. Discussion and interaction between the central location and the surveillance sites are considered essential for success, with central technical support services; continuous quality check of data to deal with errors or alerts; regular site visits and open communications; support to access raw data stored at the central location; and regular standard analyses and feedback to surveillance sites.

In the future, the capacity of countries will increase to include more diverse data sources (eg, clinical records and antibiotic usage data); to generate more sophisticated and interactive reports, analyses, and queries; and to allow the public to have access to some of the information. Delegation of the full management of the system to a central location through the use of web based applications and providing the central location with the master data are possible options for streamlining and simplifying the process (fig 1).

The building blocks of a possible solution for SEAR would include a number of key technological elements. Firstly, a local system that consists of a standalone (eg, desktop computer) application for entering data manually, which implements quality checks and generates local alerts. Secondly, an interface to extract data collected from various laboratory/hospital systems and translate it into the same common format. Finally, the system must be assisted by a central service that helps local staff (IT and end users) to set up and operate the software.

A central system will collect, collate, and check files from the surveillance sites and assemble them in a central database with access control to ensure security and confidentiality of data. A web portal could allow all sites to access and download raw data according to the permission they had received. Options for the central database will vary based on cost, the number of surveillance sites, and the country’s capacity and needs—for example, a national centre with its own servers or a regional centre using regional servers or cloud computing.

The central system needs the ability to generate predefined reports, such as alerts on data quality, standard resistance analyses, warnings about organisms or clusters of public health importance, comparison with other facilities, to send back to laboratory sites. The central database will be accessible to the central data manager and restricted staff to perform ad hoc queries (eg, SQL queries generating Excel files; box 1). The same queries and access will be granted to surveillance sites for their own data.

Box 1: Glossary of some information technology (IT) terms used in this article

Manual data entry—Entering separate items of data, one at a time in a computer interface, as opposed to submitting a file (eg, Excel) containing multiple isolates

Electronic data system—IT system used by the laboratory or hospital to store information—for example, Meditech and Cerner

Standalone or desktop application, software or interface—Software component running on a local computer independently of any network connection. In contrast to a web based system where the application cannot be accessed without an internet connection

Asynchronous data transmission—Data are transmitted as they become available and a connection to the remote system exists. For instance, as soon as a user enters a single item of information and clicks on “save,” it is sent to a server. In contrast to synchronous transfer, where data are synchronised in batches at a specific time with the remote server, with a user triggering the synchronisation or through a scheduled routine

Data extraction—Process of exporting data from a system, in this context from a specific laboratory or hospital database with its own format into a file with a more commonly used format that can then be used by another system

Data conversion or translation—Process of transforming data from one format to another. It can cover column selection and renaming, data type checks (eg, verifying that a column holds only numbers), data translation (eg, changing “male” into “M”), and file format transformations (eg, from XML to CSV)

Data collation—Process of assembling multiple datasets, typically having the same format. It can include data checks, duplicate identification, version control, etc

Surveillance site—The local laboratory or hospital which collects the original data used for surveillance

Laboratory information system—Computer software that processes, stores, and manages data from all stages of medical processes and tests. Basic laboratory information systems commonly have features that manage patient check in, order entry, specimen processing, results entry, and patient demographics

System interoperability—The ability of various IT systems and software to communicate and exchange data

SQL—Structured Query Language is a special programming language designed to communicate with a database

The purpose of such a central system is to provide a way for surveillance sites to share their data while keeping full control over it; to deliver timely central analysis; and to enable harmonisation of the central data infrastructure and the national or regional assistance/support teams. To take on these responsibilities, the central level would need to be well equipped and organised, with sufficient resources and skills, to provide training and technical support to the sites.

In the medium term, the system should grow and add components to support additional data transfer options, export from other sources, more complex graphical and interactive reports, and automated analyses that produce alerts about potential outbreaks.

We reviewed the literature, bearing in mind the above requirements, and found a few existing software options that are open access (ie, data not shown). Firstly, WHONET: desktop based software that already implements a manual data input interface, validation rules, alerts and storage as well as a data conversion component called BacLink to convert data from common laboratory and hospital systems formats. WHONET is free and has been used in >120 countries, including six in SEAR. It processes microbiology data from >2300 hospital, public health, food, and veterinary laboratories, although many of them were unable to use it to its full capacity. With proper training support at local sites, WHONET could deal with local needs. BacLink could be expanded to reinforce its capability to automate the data export. Secondly, the central level could implement an instance of JANIS: a centralised system that collects data from local surveillance sites assuming they conform to a specified standard, and can capture data from thousands of sites.15 JANIS provides a feedback report to local sites upon uploading their data, and creates annual resistance reports.15 JANIS could be complemented by a web portal to allow local and national users to download their data.

Conclusions

In summary, we have underlined the benefits and needs of IT systems to collect, process, and analyse data at a national centre as one of the priorities for improvement in the quality of national surveillance data. We proposed four guiding principles. Firstly, reliance should be on existing open access programmes and systems where further evidence of interoperability between existing systems is warranted. Secondly, the roadmap must be flexible in a rapidly changing situation where information needs, sources, and technology continue to evolve. Thirdly, this report should be seen as a first step towards further surveillance development and integration. Lastly, IT systems should be associated with continuous communication between central and local levels to improve feedback, procedures, and acceptability by local users.

The roadmap proposed in this report provides directions for countries in the region for the construction of AMR surveillance systems, acknowledging that IT systems need not be “one size fits all.” WHO, when supported by MS, will advocate that international partners should mobilise resources and leverage partnerships for technical support. WHO will subsequently work with each country to design an IT system relying on the various options proposed in fig 1. The implementation plan will be backed by training those who manage the system. There could be some system integration in support of countries’ participation in GLASS.

Contributors: SV summarised the discussions and all authors contributed and agreed on the contents of the paper.

Funding: This work was commissioned by the WHO Regional Office of South East Asia using the UK Government’s Fleming Fund. The authors alone are responsible for the views expressed in this article, which does not necessarily represent the views, decisions, or policies of the institutions with which the authors are affiliated.

Competing interests: The authors have read and understood BMJ policy on declaration of interests and declare no competing interests.

Provenance and peer review: Commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

This article is one of a series commissioned by The BMJ based on an idea from WHO SEARO. The BMJ retained full editorial control over external peer review, editing, and publication.

References

- 1.World Health Organization. United Nations high-level meeting on antimicrobial resistance. 2016. http://www.who.int/antimicrobial-resistance/events/UNGA-meeting-amr-sept2016/en/

- 2.Antimicrobial Resistance Standing Committee. National surveillance and reporting of antimicrobial resistance and antibiotic usage for human health in Australia. June 2013. https://www.safetyandquality.gov.au/wp-content/uploads/2014/02/National-surveillance-and-reporting-of-antimicrobial-resistance-and-antibiotic-usage-for-human-health-in-Australia.pdf

- 3.World Health Organization. Global action plan on antimicrobial resistance. 2015. www.who.int/antimicrobial-resistance/publications/global-action-plan/en/ [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.World Health Organization. Global antimicrobial resistance surveillance system: manual for early implementation. 2015. apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/188783/1/9789241549400_eng.pdf

- 5.World Bank. Population estimates and projections. 2017. data.worldbank.org/data-catalog/population-projection-tables

- 6.World Health Organization. Antimicrobial resistance: global report on surveillance. 2014. www.who.int/drugresistance/documents/surveillancereport/en/

- 7.Stelling J, O’Brien TF. WHONET: software for surveillance of infecting microbes and their resistance to antimicrobial agents. Chapter 48 In: Persing DH, Tenover SC, Hayden RT, et al, eds. Molecular microbiology: diagnostic principles and practice. 3rd ed. ASM Press, 2016:692-706, 10.1128/9781555819071.ch48. [Google Scholar]

- 8.World Health Organization. WHONET software. 2017. www.who.int/medicines/areas/rational_use/AMR_WHONET_SOFTWARE/en

- 9.SWEDRES-SVARM. 2013. In focus Svebar - Swedish surveillance of antimicrobial resistance, 2013:75. Solna/Uppsala, ISSN 1650-6332, https://www.folkhalsomyndigheten.se/pagefiles/17612/Swedres-Svarm-2013.pdf

- 10.Söderblom T, Billström H, Kahlmeter G, Aspevall O. The Svebar AMR surveillance group. Working with the Swedish early warning and antimicrobial resistance surveillance system SVEBAR. European Congress of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases, abstract publication, 10 May 2014, https://www.escmid.org/escmid_publications/escmid_elibrary/material/?mid=14923

- 11.European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. Antimicrobial resistance surveillance in Europe 2012. 2013. ecdc.europa.eu/en/publications/_layouts/forms/Publication_DispForm.aspx?List=4f55ad51-4aed-4d32-b960-af70113dbb90&ID=963

- 12.JANIS—Japan Nosocomial Infections Surveillance. About JANIS. https://janis.mhlw.go.jp/english/about/index.html

- 13.Morikane K. Infection control in healthcare settings in Japan. J Epidemiol 2012;22:86-90. doi:10.2188/jea.JE20110085 pmid:22307433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tanihara S, Suzuki S. Estimation of the incidence of MRSA patients: evaluation of a surveillance system using health insurance claim data. Epidemiol Infect 2016;144:2260-7. doi:10.1017/S0950268816000674 pmid:27350233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.World Health Organization, Regional Office for the Western Pacific. Biregional technical consultation on antimicrobial resistance in Asia. Meeting report. Tokyo, Japan. 2016.