Abstract

Aparna Shah and colleagues call on South East Asian countries to invest in national networks of laboratories for robust and standardised surveillance of antimicrobial resistance

Key messages

Poor infrastructure of laboratories affects surveillance of AMR in South East Asia

Developing national networks of laboratories for AMR surveillance is a priority

Standard protocols for measuring and reporting resistance must be followed

The patterns and driving forces for the emergence and spread of antimicrobial resistance (AMR) vary from place to place. Monitoring local resistance patterns helps implement targeted measures to contain AMR and to treat infections effectively. Laboratories are important for quantifying the burden of AMR and resistance patterns, and it is vital they follow standard protocols to generate quality data. Collating local data on AMR is essential to obtain a representative picture of national trends, plan and measure the effect of policies and interventions, and contribute to the understanding of AMR at a regional and global level.

In 2011 health ministers of South East Asian countries released the Jaipur declaration, signifying their commitment to work together to contain AMR.1 The declaration emphasises the need to increase capacity and share best practices for laboratory based surveillance of AMR and foster the effective use of data to modify antibiotic policy.

Regional strategies led by the World Health Organization2 3 4 recognise laboratory surveillance as a priority for controlling AMR, and countries are expected to report annually on progress. WHO organises regular meetings with representatives of national laboratories of all countries in the region5 6 7 8 to gather AMR data and discuss the challenges faced by participating laboratories.

We draw on points discussed at these meetings and suggest actions for policy makers to adopt as part of their national action plans to establish robust nationwide laboratory based surveillance mechanisms for AMR.

Poor infrastructure for laboratory based surveillance

Strengthening nationally coordinated laboratory services has, until recently, been a low priority in most South East Asian countries, with minimal funding.

A situation analysis by WHO in 2015 found that of 11 member states in region, six have a national policy or strategy on AMR, seven have a national coordinating mechanism, and nine a regulatory agency to monitor AMR.4 All of these factors affect the status of laboratory based surveillance.

All 11 member states collect data on resistance in bacteria of public health importance, though the quality and volume of data are variable. Data from laboratory surveillance also help to formulate standard treatment guidelines. All 11 member states have a list of essential medicines, but antimicrobials are available without a prescription in several countries. Nine countries reported having a national infection prevention and control programme,4 and seven reported that all their tertiary hospitals are supported by a good laboratory system.4

Nine countries have national reference laboratories for testing sensitivity to antibiotics, and six participate in external quality assessment programmes.4 The number of laboratories that meet international standards is not available. Standards such as those from the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute or the European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing are not widely used, resulting in a lack of reliable and comparable data. Some countries have no agreement on surveillance standards. Although reporting the proportions of resistant bacteria causing specific diseases or affecting defined populations is preferable, national data are often limited to proportions of resistant bacteria. Use of WHO software WHONET to monitor resistance patterns is not popular, despite free availability of the software and simplicity of use.

Information gathered by the WHO regional office shows that the quality of surveillance is dependent on the overall state and infrastructure of health laboratories in the country. In the absence of a national policy, the infrastructure, access, quality, and performance of laboratories are generally poor. Coordination between laboratories, hospital administration, and policy makers is also insufficient to share and effectively use the data.

Increasing burden of antimicrobial resistance

Data from country reports on AMR presented at regional WHO meetings5 6 7 8 and in published reports reflect an increasing trend of resistance among important bacterial pathogens. This pattern is observed in community acquired infections as well as healthcare associated or hospital transmitted infections. Although these reports give a snapshot of the situation, they fail to project an accurate picture because of the lack of nationally representative quality data.

In 2013, WHO initiated a global survey of resistance to seven pathogens of public health importance drawing from national data and published reports.9Table 1 presents information for the South East Asia region, contributed by all 11 member states. The survey confirmed that AMR is a global problem, with several developing countries reporting alarmingly high rates of resistance in most of the included pathogens.9 The high level of resistance indicates futility of use of these antibiotics as these will be therapeutically ineffective.

Table 1.

Overview of resistance in selected pathogens in South East Asia

| Organism | Resistant to | National resistance data (%)* | Published resistance data (%)* |

|---|---|---|---|

| Escherichia coli | 3rd generation cephalosporins |

16-68 | 19-95 |

| fluoroquinolones | 32-64 | 4-89 | |

| Klebsiella pneumoniae | 3rd generation cephalosporins | 34-81 | 5-100 |

| Carbapenam | 0-8 | 0-55 | |

| Meticillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) | β lactams | 10-26 | 2-81 |

|

Streptococcus

pneumoniae |

Penicillin | 47-8 | 0-6 |

| Non-typhoidal Salmonella | Fluoroquinolones | 0.2-4 | 1.4 |

| Shigella sp | Fluoroquinolones | – | 0-82 |

| Neisseria gonorrohoeae | 3rd generation cephalosporins† |

0-5 | 5-15 |

Source: WHO. Antimicrobial resistance: global report on surveillance.9

*Percentage of resistant isolates out of total isolates of bacteria that were analysed for antimicrobial susceptibility testing.

†Decreased susceptibility to 3rd generation cephalosporins.

WHO’s Gonococcal Antimicrobial Surveillance Programme (GASP) captures global data on resistance in gonococci. In six South East Asian countries gonococci have high rates of resistance to penicillin (25%-100% of isolates of gonococci tested), tetracycline (10%-100%), and ciprofloxacin (38%-100%), as well as decreased susceptibility to third generation cephalosporins, making these drugs unsuitable for treating gonococcal infections.10 Overall, over 90% of isolates that were less susceptible or resistant to penicillin and ciprofloxacin were identified from 15 laboratories in these six countries.10

A multicentre prospective study from Sri Lanka found increasing antimicrobial resistance in bloodstream infections caused by Gram negative bacilli, such as Escherichia coli.11 Multicentre studies by the Indian Network for Surveillance of Antimicrobial Resistance also show extensive drug resistance in different parts of India.12 13 In one study, meticillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus was isolated from 41% of samples at 15 tertiary care institutes over two years.12 A similar study showed high levels of resistance to nalidixic acid in Salmonella typhi and Salmonella paratyphi A.13

Similar studies are needed across the region to ascertain resistance in important pathogens. A laboratory based network in Nepal coordinated by the National Public Health Laboratory has generated valuable data on the burden of AMR of public health importance, in particular, Streptococcus pneumoniae.14 Thailand has efficiently used the results of laboratory based surveillance to generate national data on AMR, which has guided actions under its national programme.15

Initiatives to strengthen laboratory surveillance

The WHO regional office for South East Asia has supported national and regional workshops on standard laboratory methods for testing bacterial and antimicrobial susceptibility to enhance capacity for laboratory surveillance. The objective is to encourage member states to establish national laboratory networks for wider surveillance, ensure compliance with standards, and produce comparable results. Although AMR surveillance has largely been laboratory based, there is also a push towards gathering demographic and epidemiological data to link with antimicrobial susceptibility patterns identified in laboratories, and accurately assess the effect on public health.

WHO has launched a Global Antimicrobial Resistance Surveillance System (GLASS) to standardise AMR surveillance. This system collects and reports data on AMR rates aggregated at national level and is expected to enable comparable and validated data to be shared between countries to drive local, national, and regional action. Epidemiological and microbiological information will be combined to enhance understanding of the extent and impact of AMR on populations, detect emerging resistance and monitor trends, and measure the effectiveness of interventions to control AMR. Countries can enrol to participate in GLASS.

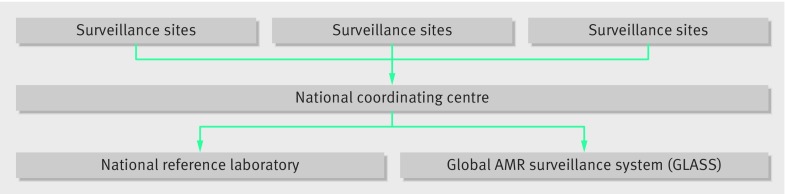

Figure 1 outlines components of the surveillance system recommended as part of GLASS. Several institutes in South East Asia undertake antimicrobial susceptibility but the data generated are not comparable or are not shared to enable appropriate response. GLASS should help overcome these problems and build capacity for systematic national surveillance.

Fig 1 Components of GLASS

Way forward

Laboratory based surveillance is crucial to understand the burden of resistance as well as the effectiveness of interventions. Overall, South East Asian countries have limited capacity for national surveillance. National action plans must accord sufficient importance to strengthening laboratories and networks to undertake AMR surveillance.

Access to laboratory services needs to be urgently expanded. Currently, most AMR surveillance is limited to national or regional laboratories, leaving the district laboratories out of any surveillance network. This must change to obtain accurate national data. As well as increasing the number of laboratories participating in the AMR network, governments must ensure adequate skilled staff, functional equipment, a continuous supply of reagents, standardised technology, and sustainable funding. National networks need to be initiated and strengthened for generating nationally representative data.

Simple microbiological techniques to determine drug susceptibility of bacteria are available in several laboratories. However, laboratories must follow a standard protocol to measure and report resistance. Gathering data is not enough. Information must be able to be shared with decision makers to enhance public health knowledge and guide policy making at national and regional levels, while informing patient diagnosis and care at the local level.16 Active collaboration between laboratories in public and private sector as well as between human health and animal health is also critical.

Participation in the GLASS programme will help countries develop a realistic national action plan for AMR and efficiently monitor their progress.17 There is clearly a case for greater investment in health laboratories that will ensure integrated surveillance of AMR in humans and animals, and in disease specific control programmes.

Contributors and sources: Most of the authors are or were directors of national public health laboratories or national centres for disease control of member states of the WHO South East Asia region. Authors and contributors have been national representatives for sharing national data with the global community. All the PHLs directors are or were also national AMR laboratory focal points and associated with generation of antimicrobial susceptibility data in their respective countries. These data were presented in WHO intercountry or regional meetings, and some are published in WHO global reports and other publications on AMR. AS wrote the first draft of the manuscript and subsequent revision, and interpreted it in collaboration with the other authors.

Competing interests: All authors have reported receiving no support from any organisation for the submitted work. These are official national reports submitted on behalf of national governments in WHO meetings.

Provenance and peer review: Commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

This article is one of a series commissioned by The BMJ based on an idea from WHO SEARO. The BMJ retained full editorial control over external peer review, editing, and publication.

References

- 1.Jaipur Declaration on Antimicrobial Resistance. 2016.http://www.searo.who.int/entity/antimicrobial_resistance/rev_jaipur_declaration_2014.pdf?ua=1.

- 2.World Health Organization. Asia Pacific strategy for strengthening health laboratory services (2010-2015). 2010 http://apps.searo.who.int/PDS_DOCS/B4531.pdf?ua=1.

- 3.World Health Organization. Regional strategy on prevention and containment of antimicrobial resistance 2010-2015. http://www.searo.who.int/entity/antimicrobial_resistance/documents/sea_hlm_407/en/.

- 4.World Health Organization. Worldwide country situation analysis: response to antimicrobial resistance. 2016. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/163468/1/9789241564946_eng.pdf.

- 5.World Health Organization. Report of a bi-regional workshop on laboratory based surveillance of antimicrobial resistance, Chennai, India, 21-25 March 2011. 2011. http://www.searo.who.int/entity/antimicrobial_resistance/BCT_Reports_SEA-HLM-420.pdf.

- 6.World Health Organization. Report of regional workshop on antimicrobial resistance, Bangkok, Thailand 6-10 August 2012. 2012. http://www.searo.who.int/entity/antimicrobial_resistance/documents/CDS_SEA-CD-258.pdf.

- 7.World Health Organization. Report of a regional workshop on laboratory-based surveillance of antimicrobial resistance, Chennai, India 17-21 June 2012. 2013. http://www.searo.who.int/entity/antimicrobial_resistance/sea_cd_273.pdf?ua=1.

- 8.World Health Organization. Report of regional workshop on antimicrobial resistance, Jaipur, India 10-13 November 2014. 2014. http://www.searo.who.int/entity/antimicrobial_resistance/sea_hlm_423.pdf.

- 9.World Health Organization. Antimicrobial resistance: global report on surveillance. 2014. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/112642/1/9789241564748_eng.pdf.

- 10.Bala M, Kakran M, Singh V, Sood S, Ramesh V. Monitoring antimicrobial resistance in Neisseria gonorrhoeae in selected countries of the WHO South-East Asia Region between 2009 and 2012: a retrospective analysis. Sex Transm Infect 2013;89(Suppl 4):iv28-35. 10.1136/sextrans-2012-050904. pmid:24243876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chandrasiri P, Elwitigala J, Nanayakkara G, et al. A multi centre laboratory study of Gram negative bacterial blood stream infections in Sri Lanka. Ceylon Med J 2013;58:56-61. 10.4038/cmj.v58i2.5680. pmid:23817934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Joshi S, Ray P, Manchanda V, et al. Methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) in India: prevalence & susceptibility pattern. Indian J Med Res 2013;137:363-9.pmid:23563381. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Joshi S. Indian Network for Surveillance of Antimicrobial Resistance (INSAR) group. Antibiogram of S. enterica serovar Typhi and S. enterica serovar Paratyphi A: a multi-centre study from India. WHO South East Asia J Public Health 2012;1:182-8. 10.4103/2224-3151.206930 pmid:28612793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Geeta S, Adhikari BR. Ten years surveillance of antimicrobial resistance pattern of Streptococcus pneumoniae in Nepal. Afr J Microbiol Res 2012;6:4233-8. 10.5897/AJMR11.606. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Thamlikitkul V, Rattanaumpawan P, Boonyasiri A, et al. Thailand antimicrobial resistance containment and prevention program. J Glob Antimicrob Resist 2015;3:290-4. 10.1016/j.jgar.2015.09.003. pmid:27842876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.World Health Organization. Global Antimicrobial Surveillance System, Manual for early Implementation. Geneva: WHO Press 2015. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/188783/1/9789241549400_eng.pdf.

- 17.Nugent R, Back E, Beith A. The race against drug resistance.Center for Global Development, 2010. [Google Scholar]