Abstract

To report a rare case of infectious keratitis after collagen cross-linking (CXL) for keratoconus. A 20-year-old male patient underwent CXL for keratoconus in his right eye. Four weeks after the procedure, he reported blurred vision and redness with increasing pain in the treated eye. Ophthalmic examination revealed a corneal epithelial defect with corneal infiltrates that exhibited branching needle-like opacities. The patient was diagnosed with infectious crystalline keratopathy (ICK). Corneal scrapings and culture indicated the presence of Streptococcus sanguinis. The patient was successfully treated with fortified vancomycin and ceftazidime over several weeks. ICK is a potential post-operative complication of CXL that can lead to corneal scarring with a permanent reduction in visual acuity.

Keywords: Corneal cross-linking, infectious crystalline keratopathy, keratitis, streptococcus

Introduction

Collagen cross-linking (CXL) treatment with a photosensitizer (riboflavin) and ultraviolet A (UVA) light induces a series of microstructural alterations in corneal collagen that increases the tensile strength of the cornea in patients with keratoconus.[1] CXL has been a common treatment to halt the progression of this disease. Although the safety and efficacy of CXL have been previously documented,[1] complications have also been reported, including temporary corneal haze, bullous keratopathy, microbial keratopathy, corneal scarring, sterile infiltrates, and secondary infection.[2] These complications usually result from inaccurate technique, poor patient hygiene, or concurrent ocular surface pathology.[2] We report a case of infectious crystalline keratopathy (ICK) after CXL treatment in a patient with progressive keratoconus. To the best of our knowledge, this is the case report in the English and non-English peer-reviewed literature.

Case Report

A 20-year-old male patient underwent CXL for keratoconus in his right eye. The treatment was performed under sterile conditions using pre-operative topical anesthesia. A blunt knife was used to remove the central 7.0–8.0 mm of corneal epithelium. Riboflavin 0.1% solution (10 mg riboflavin-5-phosphate in 10 mL dextran 20% solution) was applied every 2 min for 30 min. Followed by exposure of UVA (365 nm, 3 mW/cm2).

A bandage contact lens was placed over the eye at the end of the procedure. Post-operative medications included topical ofloxacin 0.3% and prednisolone acetate 1% both applied 4 times daily for 1 week. The patient was followed up on a daily basis. On the 3rd day, the corneal epithelial defect was completely healed and the bandage contact lens removed. The patient's immediate postoperative course was uneventful.

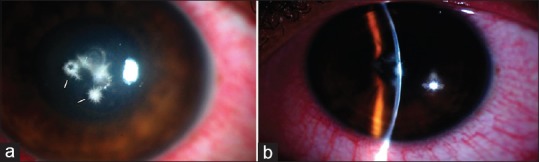

Four weeks after the procedure, the patient presented to the emergency room with a 1-week history of blurred vision and redness with increasing pain in the treated eye. On examination, the best-corrected visual acuity (BCVA) was 20/40. Slit-lamp examination indicated diffuse conjunctival injection and deep multiple infiltrates in the central corneal stroma with branching needle-like opacities, consistent with ICK [Figure 1]. Fluorescein staining revealed a corneal epithelium defect. There was moderate anterior chamber reaction. Examination of the left eye did not reveal any abnormalities.

Figure 1.

(a and b) Slit-lamp examination of the right eye showed diffuse conjunctival injection and multiple white, needle-like, branching stromal infiltrates

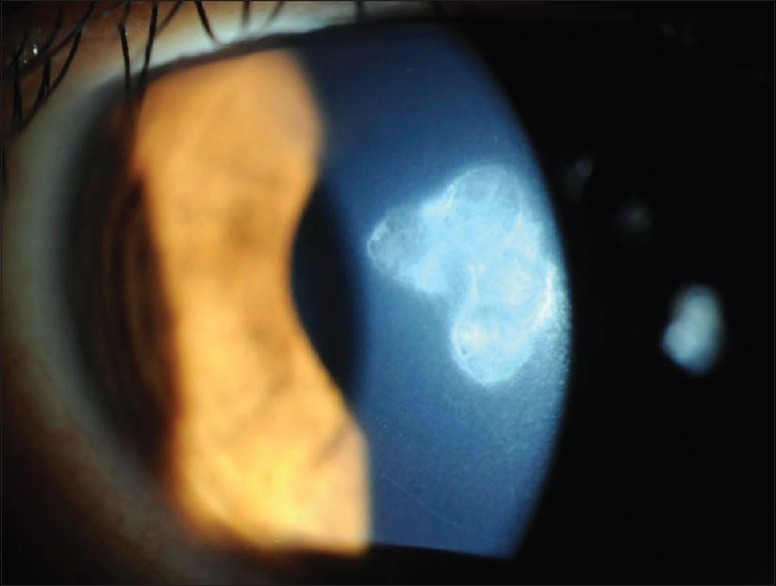

Corneal scrapings were taken for microbiological staining and inoculated for culture. The organism was identified as Streptococcus sanguinis, which is sensitive to moxifloxacin, vancomycin, oxacillin, and ceftazidime. The patient was treated with hourly topical vancomycin (50 mg/0.1 mL) and ceftazidime (50 mg/0.1 mL) fortified eye drops. The antibiotics were reduced to five times daily 3 days after presentation and slowly tapered after the infiltrates began to resolve and the epithelial defect healed. Six weeks later, the density of the infiltrates decreased and topical antibiotics were discontinued. Eight weeks after presentation, the BCVA was 20/30 and there was complete resolution of the infiltrates with a faint residual avascular corneal scar [Figure 2].

Figure 2.

Eight weeks after topical antibiotic treatment, stromal infiltration has resolved and resulted in an avascularized stromal scar

Discussion

ICK is a chronic corneal infection characterized by infiltration in a needle-like configuration at all levels of the corneal stroma.[3] It results from stromal colonization by microorganisms without adjacent inflammatory reaction but with preservation of the stromal structure.[3] Biofilm formation is considered important in the pathogenesis of ICK. The bacteria are enveloped in a biofilm composed of an exopolysaccharide glycocalyx.[4] The biofilm isolates the infectious organisms from the immune system, making them impervious to antimicrobial penetration.[4]

Risk factors for ICK include previous corneal surgery, long-term corticosteroid use, prior corneal disease, and systemic immunocompromise.[3] ICK has been reported after cataract extraction, penetrating keratoplasty, corneal refractive surgery, and glaucoma filtering surgery.[3,4]

The most common organisms associated with ICK are the viridans group of streptococci.[4] Other causative organisms include Streptococcus pneumoniae, Haemophilus aphrophilus, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa.[5] Candida have also been implicated.

S. sanguinis was the causative organism in the current case. Formerly known as S. sanguis, S. sanguinis is a Gram-positive facultative anaerobic bacteria and a member of the viridans streptococci group.[6] The infection responded well to topical antibiotics. This therapy minimized the risk of recurrence, mitigated further sequelae, and maintained vision at 20/30.

Ironically, although infectious keratitis can occur after CXL, this treatment is a viable option for corneal melts or severe unresponsive infectious keratitis because CXL strengthens a collagenolytic cornea, whereas UVA irradiation eliminates the infectious agent.[7]

This case report illustrates the development of ICK 4 weeks after CXL treatment. One possible explanation is that CXL enlarges the intralamellar space and favors the ingrowth of bacteria in the corneal stroma.[5] In general, the cornea is most susceptible to infection during epithelial healing. The use of bandage contact lenses may decrease healing time but increase the risk of infection associated with manipulation of the contact lens.[7] Our patient showed complete epithelial healing after the CXL procedure. Nonetheless, he presented with ICK 4 weeks later, an unusual development after CXL treatment.

Although infectious keratitis after CXL is a rare complication, maintaining sterile conditions during the procedure and providing appropriate antibiotic prophylaxis are warranted to mitigate the risk of this vision-threatening infection, which can lead to corneal scarring and a permanent reduction in visual acuity.

The patient provided written consent for publication of personal information, including medical record details and photographs.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Parker JS, van Dijk K, Melles GR. Treatment options for advanced keratoconus: A review. Surv Ophthalmol. 2015;60:459–80. doi: 10.1016/j.survophthal.2015.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dhawan S, Rao K, Natrajan S. Complications of corneal collagen cross-linking. J Ophthalmol. 2011;2011:869015. doi: 10.1155/2011/869015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sharma N, Vajpayee RB, Pushker N, Vajpayee M. Infectious crystalline keratopathy. CLAO J. 2000;26:40–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Masselos K, Tsang HH, Ooi JL, Sharma NS, Coroneo MT. Laser corneal biofilm disruption for infectious crystalline keratopathy. Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2009;37:177–80. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-9071.2008.01912.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Khan IJ, Hamada S, Rauz S. Infectious crystalline keratopathy treated with intrastromal antibiotics. Cornea. 2010;29:1186–8. doi: 10.1097/ICO.0b013e3181d403d4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Krzysciak W, Pluskwa KK, Jurczak A, Koscielniak D. The pathogenicity of the Streptococcus genus. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2013;32:1361–76. doi: 10.1007/s10096-013-1914-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Abbouda A, Abicca I, Alió JL. Infectious keratitis following corneal crosslinking: A systematic review of reported cases: Management, visual outcome, and treatment proposed. Semin Ophthalmol. 2016;31:485–91. doi: 10.3109/08820538.2014.962176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]