Abstract

PURPOSE:

Monitoring the visual acuity following cataract surgery is used as a measure of the quality of the surgery in blindness prevention programs in middle- and low-income countries. While the day 1 visual acuity is usually available, the (final) visual acuity after several weeks may not be available, as the majority of patients may not return for review. This study was undertaken to ascertain if the early and late visual acuities are correlated and if the day 1 visual acuity can be used to predict the likely final visual acuity.

METHODS:

A retrospective case note review was undertaken of all eyes having cataract surgery over a 6-month period.

RESULTS:

There was a positive correlation between the day 1 and week 6 visual acuities in both the World Health Organization categories (Spearman coefficient = 0.4666, P = 0.001) and the logMAR visual acuity scores (Spearman coefficient = 0.5425, P = 0.001).

CONCLUSION:

In blindness prevention programs in middle- and low-income countries with poor postoperative follow-up where it is not possible to document the final visual acuity in all the operated cases, there is merit in documenting and monitoring the day 1 visual acuity as a quality control measure.

Keywords: Cataract surgery outcome, cataract surgery postoperative visual acuity, cataract surgery quality monitoring

Introduction

Cataract is the leading cause of global blindness, responsible for about 50% of cases.[1] To eliminate blindness due to cataract, the provision of high volume, high quality, low-cost surgery is recommended.[2] Monitoring the visual acuity following surgery is used as a measure of the quality of the surgery, and the World Health Organization (WHO) has recommendations for the acceptable proportions of eyes in different vision categories on day 1 following surgery and at final follow-up after surgery.[3] However, poor follow-up after surgery in middle- and low-income countries makes the assessment of the surgery quality and the visual acuity outcome uncertain. While it is possible to measure the visual acuity on day 1 following surgery before the patient is discharged, the (final) visual acuity after several weeks may only be obtainable in a small proportion of patients, as the majority of patients do not return for review.[4] The overall early and late visual outcomes for eye units in different hospitals have been found to be correlated.[5] It would be most useful to know if the early and late visual outcomes in individual patients are correlated and if the day 1 visual acuity can be used to predict the likely final visual acuity in an individual patient.

This study was undertaken to assess if there is a correlation between the day 1 visual acuity and the visual acuity at final follow-up after 6 weeks and to identify factors that might affect that correlation.

Methods

Ethical approval for the study was obtained from the Human Research Ethics Committee, and the study was conducted in compliance with the Helsinki Declaration.

The case notes of all patients having cataract surgery over a 6-month period were reviewed. Patients having cataract surgery who live within the city metro have their surgery done as day cases, while those who live outside the city are admitted for 1 night after their surgery. They are all reviewed on day 1 after their surgery and then again after 6 weeks. The autorefraction is checked at each review to exclude significant astigmatism or refraction surprise from a biometry error, but subjective refractions are not done and best-corrected visual acuities are not recorded. Patients requiring refraction correction after surgery are referred to an optometrist at a secondary level community health center.

Data were extracted on the patients' gender, the patients' age, preoperative pathology, intraoperative complications, the presence or absence of corneal edema on day 1 and the presenting visual acuities on day 1 and at final follow-up after 6 weeks. The Snellen visual acuities were converted to logMAR visual acuities.[6]

The data were entered on a Microsoft XL worksheet, and the data were analyzed using Stata 12.0 (StataCorp). The correlations between the day 1 and week 6 visual acuities were calculated, using both the logMAR visual acuities and the WHO visual acuity categories. A multivariate analysis was done to assess if intraoperative complications (posterior capsule rupture, zonular dehiscence, and vitreous loss) or day 1 postoperative corneal edema might affect the association between the day 1 and final visual acuities at week 6.

Results

There were 603 cataract surgeries done in the 6-month period between July and December 2014. Three hundred and ninety-three surgeries (65.2%) were done on females and 210 surgeries (34.8%) were done on males. The age range of the patients was 13–100 years, with a mean age of 67 years (standard deviation 13 years).

Five hundred and eighty-four cases (96.8%) were seen on day 1 after surgery and 502 (83.3%) were seen at week 6.

Twenty-six cases (4.3%) had intraoperative posterior capsule rupture, 23 cases (3.8%) intraoperative zonular dehiscence, 15 cases (2.5%) intraoperative vitreous loss, and 38 cases (6.5%) corneal edema on day 1.

Corneal edema on day 1 was positively correlated with the intraoperative complications of posterior capsule rupture (χ2 = 10.44, P = 0.001), vitreous loss (χ2 = 4.27, P = 0.039), and zonular dehiscence (χ2 = 5.70, P = 0.016).

Of the 584 cases seen on day 1, 79 (13.5%) were noted to have diabetic retinopathy and 37 (6.3%) were noted to have glaucomatous optic neuropathy. Similarly, of the 502 cases seen at 6 weeks, 71 (14.1%) were noted to have diabetic retinopathy and 33 (6.5%) were noted to have glaucomatous optic neuropathy.

The mean day 1 logMAR visual acuity was 0.72 and the mean final visual acuity at week 6 was 0.4.

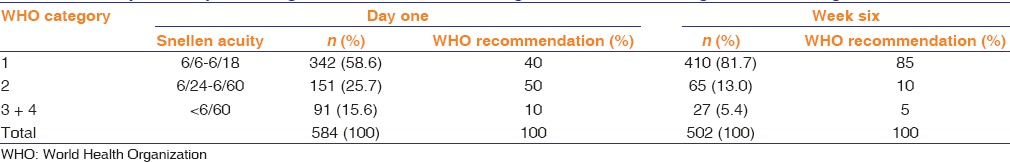

The day 1 and week 6 visual acuity outcomes according to the WHO vision categories are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Postoperative presenting visual acuities according to World Health Organization categories

There was a positive correlation between the day 1 and week 6 visual acuities in the WHO categories (Spearman coefficient = 0.4666, P = 0.001) and in the logMAR visual acuity scores (Spearman coefficient = 0.5425, P = 0.001).

Intraoperative zonular dehiscence and vitreous loss and day 1 postoperative corneal edema significantly weakened the correlation between the logMAR visual acuities (Spearman coefficient = 0.4220, P = 0.001 and Spearman coefficient = 0.4846, P = 0.001), while posterior capsule rupture did not significantly affect this correlation (Spearman coefficient = 0.4008, P = 0.667).

Eyes with good vision on day 1 (category one) have an 80% chance of remaining in category 1 (272 of 342 eyes). Eyes with poor vision on day 1 (categories 3 and 4) have a 21% chance of remaining with poor vision (19 of 91 eyes). Of these, eyes without corneal edema have a 19% chance of improving to good vision (3 of 16 eyes), while eyes with corneal edema have a 44% chance of improving to good vision (33 of 75 eyes).

Discussion

Our study shows a good correlation between the day 1 visual acuity and the week 6 visual acuity, using both individual logMAR visual acuities and WHO categories. Corneal edema on day 1 weakened this correlation, and this was associated with intraoperative complications of zonular dehiscence and vitreous loss. Eyes in category one on day 1 are likely to remain in this category. Eyes in categories 3 and 4 on day 1 without corneal edema are less likely to improve to category 1, whereas eyes with corneal edema are more likely to improve to category 1. Overall, as we might expect, there is an improvement in visual acuity from day 1 to week 6 (59% to 82% in category 1, 26% to 13% in category 2, and 16% to 5% in categories 3 and 4).

Two-thirds of surgeries were on females and one-third on males. We do not have data on the etiology of cataracts in this cohort of patients, but most of the adult cataracts seen in our clinic are age related. Female gender has been reported as a barrier to cataract surgery uptake in a number of blindness prevention programs in middle- and low-income countries, and specific strategies have been recommended to deal with this gender inequity.[7] The reverse gender inequity in our patients is, therefore, interesting and noteworthy.

The loss to follow-up after cataract surgery in middle- and low-income countries is well recognized, and follow-up rates as low as 20% have been reported.[8] Over 80% of our patients returned for follow-up after 6 weeks, which allowed for comparison of the day 1 and week 6 visual acuities in this majority of patients.

While the proportions of eyes with good vision on day 1 and at week 6 compare favorably with the WHO recommendations, the proportions of eyes with poor vision on day 1 and at week 6 compare unfavorably with the WHO recommendations. From our study, we do not know the reasons for the poor vision in these eyes (whether other eye pathology, intraoperative or postoperative complication, or uncorrected refractive error).[4] Fourteen percent of the operated eyes were noted to have associated diabetic retinopathy, and it is probable that associated diabetic retinopathy is a common cause of poor vision following cataract surgery in our patients.

There are a number of weaknesses with our study. This was a retrospective case note review and not a prospective study. Our follow-up rate of <100% may bias the correlations we have found. Our refraction services are provided at secondary level community health centres, and patients requiring refraction correction after surgery are referred to an optometrist working at a community health center. While we check the autorefraction on all our patients after surgery, to exclude significant astigmatism or a refraction surprise from biometry error requiring further intervention, we do not routinely perform a subjective refraction, and we do not have available data on the best-corrected visual acuities. We have, therefore, only compared the day 1 presenting visual acuities with the week 6 presenting visual acuities.

Notwithstanding these weaknesses, in the absence of corneal edema on day 1, there is a good correlation between the day 1 visual acuity and the week 6 visual acuity. In blindness prevention programs in middle- and low-income countries with poor postoperative follow-up where it is not possible to document the final visual acuity in all the operated cases, there is still merit in documenting and monitoring the day 1 visual acuity as a quality control measure.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Pascolini D, Mariotti S. Global estimates of visual impairment 2010. Br J Ophthalmol. 2012;96:614–18. doi: 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2011-300539. https://www.iapb.org/wp-content/uploads/WHO-Global-Data-on-Visual-Impairments-2010.pdf . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brian G, Taylor H. Cataract blindness – Challenges for the 21st century. Bull World Health Organ. 2001;79:249–56. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dandona L, Limburg H. What do we mean by cataract outcomes? Community Eye Health. 2000;13:35–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Limburg H, Foster A, Gilbert C, Johnson GJ, Kyndt M, Myatt M. Routine monitoring of visual outcome of cataract surgery. Part 2: Results from eight study centres. Br J Ophthalmol. 2005;89:50–2. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2004.045369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Congdon N, Yan X, Lansingh V, Sisay A, Müller A, Chan V, et al. Assessment of cataract surgical outcomes in settings where follow-up is poor: PRECOG, a multicentre observational study. Lancet Glob Health. 2013;1:e37–45. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(13)70003-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Holladay JT. Proper method for calculating average visual acuity. J Refract Surg. 1997;13:388–91. doi: 10.3928/1081-597X-19970701-16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lewallen S, Mousa A, Bassett K, Courtright P. Cataract surgical coverage remains lower in women. Br J Ophthalmol. 2009;93:295–8. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2008.140301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bani A, Wang D, Congdon N. Early assessment of visual acuity after cataract surgery in rural Indonesia. Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2012;40:155–61. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-9071.2011.02667.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]