Abstract

Purpose:

Cancer is the leading cause of nonaccidental death among adolescents and young adults (AYAs). High-intensity end-of-life care is expensive and may not be consistent with patient goals. However, the intensity of end-of-life care for AYA decedents with cancer—especially the effect of care received at specialty versus nonspecialty centers—remains understudied.

Methods:

We conducted a retrospective, population-based analysis with the California administrative discharge database that is linked to death certificates. The cohort included Californians age 15 to 39 years who died between 2000 and 2011 with cancer. Intense end-of-life interventions included readmission, admission to an intensive care unit, intubation in the last month of life, and in-hospital death. Specialty centers were defined as Children’s Oncology Group centers and National Cancer Institute–designated comprehensive cancer centers.

Results:

Of the 12,938 AYA cancer decedents, 59% received at least one intense end-of-life care intervention, and 30% received two or more. Patients treated at nonspecialty centers were more likely than those at specialty-care centers to receive two or more intense interventions (odds ratio [OR], 1.46; 95% CI, 1.32 to 1.62). Sociodemographic and clinical factors associated with two or more intense interventions included minority race/ethnicity (Black [OR, 1.35, 95% CI, 1.17 to 1.56]; Hispanic [OR, 1.24; 95% CI, 1.12 to 1.36]; non-Hispanic white: reference), younger age (15 to 21 years [OR, 1.36; 95% CI, 1.19 to 1.56; 22 to 29 years [OR,1.26; 95% CI,1.14 to 1.39]; ≥ 30 years: reference), and hematologic malignancies (OR, 1.53; 95% CI, 1.41 to 1.66; solid tumors: reference).

Conclusion:

Thirty percent of AYA cancer decedents received two or more high-intensity end-of-life interventions. In addition to sociodemographic and clinical characteristics, hospitalization in a nonspecialty center was associated with high-intensity end-of-life care. Additional research is needed to determine if these disparities are consistent with patient preference.

INTRODUCTION

Cancer is the leading cause of nonaccidental death among adolescents and young adults (AYAs; ages 15 to 39 years) in the United States.1 Despite approximately 9,000 cancer deaths in AYAs annually, there is a paucity of literature about end-of-life care for AYAs with cancer.2 End-of-life care is determined by many interacting factors. Inpatient intensity, timely hospice referrals, pain control, and caregiver outcomes are just some important end-of-life outcomes. Treatment center, local resources, patient and provider characteristics, and patient and caregiver preferences are important determinants of a patient’s end-of-life care. How these determinants influence end-of-life care is not clearly understood, particularly at a population level. In this study, we address this gap by determining the impact of treatment center and patient characteristics on one aspect of AYA oncology end-of-life care—inpatient intensity—with a population-level approach.

End-of-life care intensity receives much attention in older cancer decedents because of concerns that high-intensity care is expensive, is inconsistent with goal-concurrent end-of-life care, may be futile, and may actually harm the patient or caregivers. ASCO and other professional organizations advocate for a palliative approach to patients with life-threatening illnesses.3-7 The National Quality Forum endorses many intensity markers for cancer decedents. In two prior studies, approximately two thirds of AYAs with cancer received intense end-of-life care, and disparities were based on primary cancer diagnosis, patient age, and family income.8,9 However, these studies examined single-payer populations, which limits generalizability.

The prevalence of and factors associated with AYA end-of-life care intensity at a full population level remain unstudied. It is critical to determine how the site of care influences AYA end-of-life oncology care in addition to a determination of how other clinical and sociodemographic factors influence end-of-life care in a diverse population. This study addresses these gaps through a population-based approach that has sufficient population heterogeneity to examine the impact of site of care, clinical factors, and sociodemographic factors on intensity of end-of-life care in AYA cancer decedents.

METHODS

Study Design and Oversight

We conducted a retrospective (2000 to 2011) population-based analysis with the California Office of Statewide Health Planning and Development (OSHPD) Private Patient Discharge Data and Vital Statistics Death Certificate data. All California hospitals, except federal facilities and prison hospitals (> 500 hospitals), are required to submit information to OSHPD. The discharge and death certificate databases are linked with unique record linkage numbers for 2000 to 2011. OSHPD includes the following information on each discharge: age, race/ethnicity, sex, residence zip code, payer, length of stay, and up to 24 International Classification of Diseases (ninth revision; ICD9) codes. The Stanford University investigational review board and the California Committee for Protection of Human Subjects approved the study. Reporting guidelines for an administrative data study were followed.13

Study Population

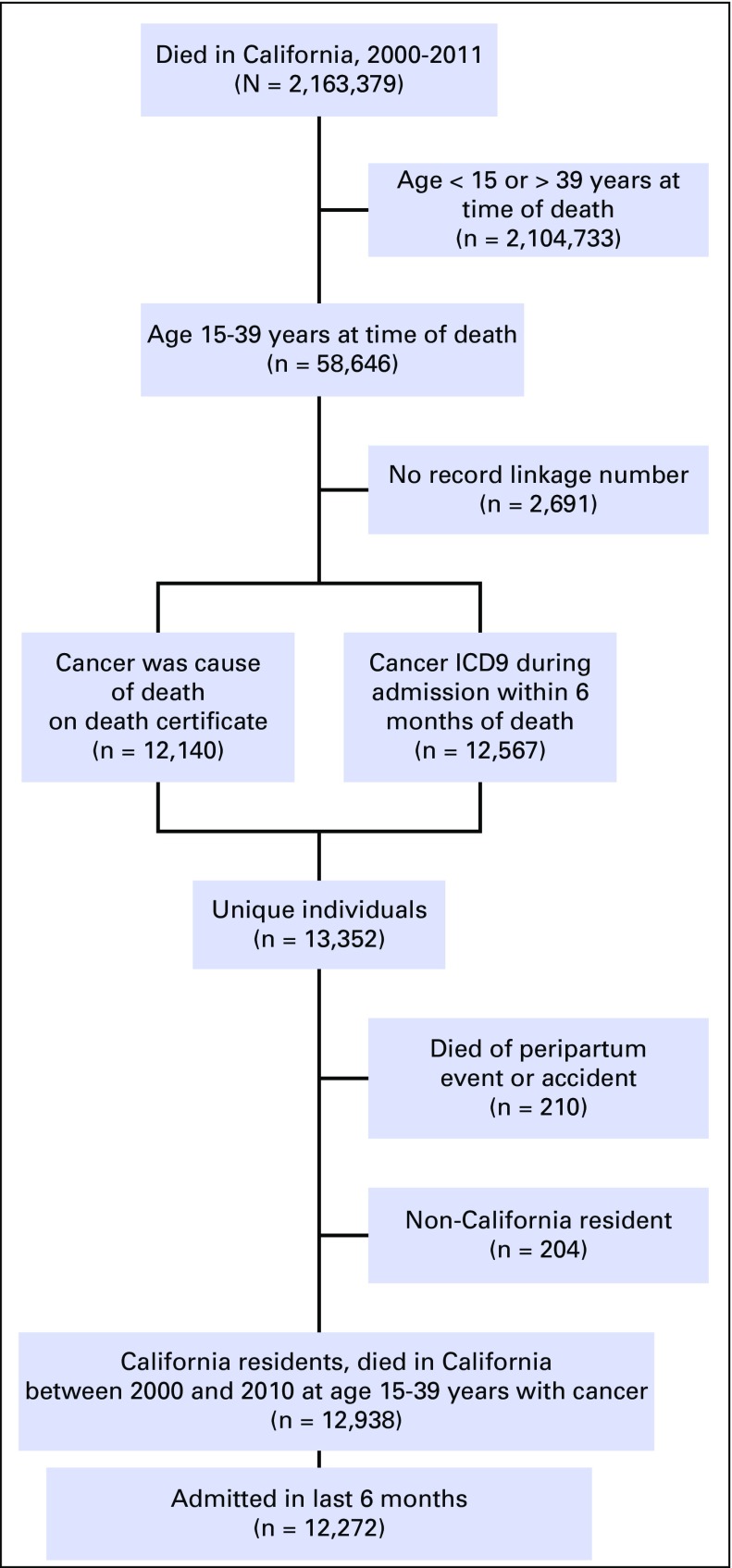

The study population included patients age 15 to 39 years at the time of death who died between 2000 and 2011 and who had an oncologic diagnosis during any hospitalization within 6 months of death or cancer as a cause of death (Fig 1). A list of oncologic ICD9 codes was developed by combining the Clinical Classification Software oncology diagnoses and oncologic ICD9 codes previously used in the OSHPD database.11,14 Potential nonmalignant conditions, such as carcinomas in situ and abnormal Papanincolaou smears, were removed. The resulting diagnoses were grouped according to AYA site categories of the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program.15 Four oncologists independently reviewed the list for completeness and accuracy. Death certificate cause-of-death categories for malignant neoplasms (C00 to C97) were included. Patients who died as a result of accidents or peripartum events were excluded.

Fig 1.

Study population: California residents who died in California between 2000 and 2011 at age 15 to 39 years with cancer (but death was not a result of peripartum events or accidents). ICD9, International Classification of Diseases, ninth revision

Dependent Variables

The markers of intensity used in this study were previously developed and validated, and many are endorsed by the National Quality Forum.16-19 They include admission to an intensive care unit (ICU), intubation or mechanical ventilation, tracheostomy placement, gastrostomy tube placement, hemodialysis, cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR), readmission in the last 30 days of life, and in-hospital death.16-19 ICD9 codes for intensity were described previously for all except ICU admission, which is not directly coded.16 ICU admission was determined by a code for intubation, mechanical ventilation, arterial catheterization, or central venous pressure monitoring. A patient was considered a recipient of an intervention if it was coded during an admission that took place entirely within the timeframe of interest. Location of death was determined from death certificates or hospital disposition of death.

Specialty centers (SCs) were defined as Children’s Oncology Group (COG) centers for those younger than age 18 years and as National Cancer Institute (NCI)–designated comprehensive cancer centers and/or COG centers for those age 18 years or older. NCI-designated centers were not considered SCs for patients younger than age 18 years, because pediatric patients have improved outcomes when treated at pediatric centers (ie, COG centers). COG centers were considered SCs for all ages, because many pediatric cancers can occur in young adults who benefit from pediatric centers, and because some patients would have been diagnosed before age 18 years, been appropriately treated at a COG center at diagnosis, and then remained there for continuity of care. Patients were classified according to their admissions in the last 6 months as only SC hospitalizations or as all other hospitalization combinations.

Independent Variables

The sociodemographic variables included payer (health maintenance organization [HMO], private insurance, and public or no insurance), death age, sex, race/ethnicity, median household income (from zip code–level median household income and the 2004 federal poverty level [FPL]), and metropolitan statistical area.20,21 They were pulled from death certificate information, when available, or from last hospital admission otherwise. Distance between hospitals and the center-of-residence zip code was calculated between the residence and (1) the last hospital and (2) the closest SC. Cancer diagnoses were determined as described in the Study Population section and grouped into hematologic malignancies (leukemia and lymphoma) and nonhematologic malignancies (solid tumors). The Elixhauser comorbidity score was chosen, because it was developed with the OSHPD database and included oncology patients.22,23 Each patient scored one point for each nononcologic comorbidity category present during the final admission.24 Interactions between age and specialty center, specialty care and diagnosis, age and diagnosis, and diagnosis and race/ethnicity were examined.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were calculated for each independent and dependent variable.

Prevalence of intense end-of-life care interventions

Patients were categorized by the number of intense interventions received. Frequency counts were performed for the entire cohort (N = 12,938).

Predictors of intensity of end-of-life care

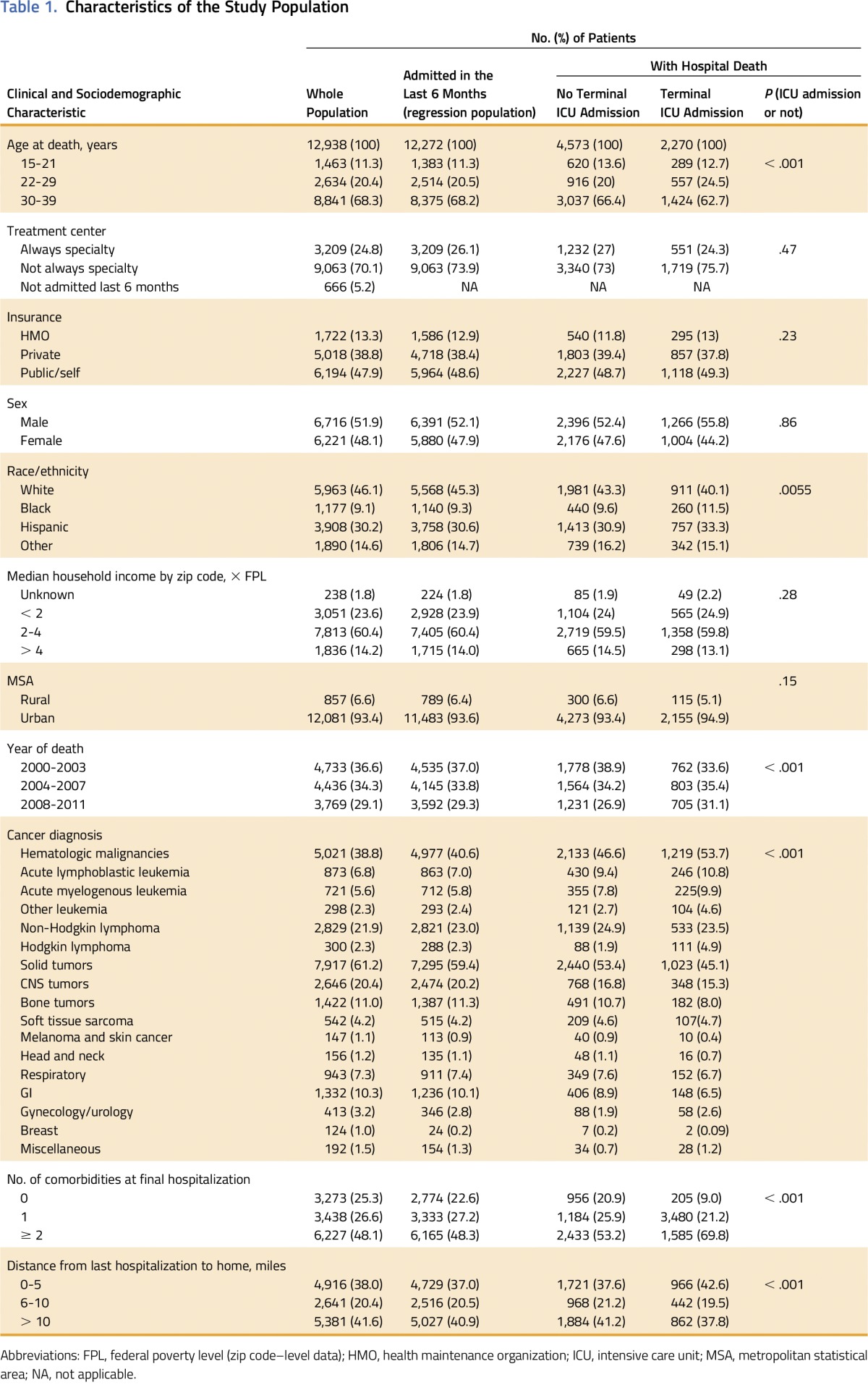

With the a priori independent variables, logistic regression models were constructed to determine factors associated with each intensity marker and with receipt of two or more intensity markers. Only the 12,272 patients (94% of the cohort) admitted in the last 6 months were used in the regression to ensure accurate insurance, comorbidity, and distance information. The clinical and sociodemographic characteristics of these 12,272 patients were similar to those of the whole cohort (Table 1). A sensitivity analysis was conducted in which intubation or mechanical ventilation with ICU admission was only counted as one intensity marker instead of as two separate intensity markers.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the Study Population

Predictors of end-of-life care location

Logistic regression models also were constructed to determine sociodemographic factors and diagnoses associated with SC hospitalization in the last 6 months. Some patients prefer hospital death, but such deaths would most likely occur on the floor rather than in the ICU, so patients with a terminal admission with and without an ICU admission were compared.

Regression results

Adjusted odds ratios (ORs) and 95% CIs are reported. SAS version 9.1 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC) was used.

RESULTS

Study Population Characteristics

There were 12,938 patients in the study population (Fig 1). In the last 6 months of life, 25% of the patients were hospitalized only at a SC, 70% were hospitalized at a nonspecialty center at least once, and 5% were not hospitalized. Solid tumors (61%) were more common than hematologic malignancies (39%). The most common single diagnoses were CNS tumors (20%) and non-Hodgkin lymphoma (22%). Two thirds (68%) of the patients were age 30 years or older at the time of death; 46% were non-Hispanic white, and 30% were Hispanic. Almost half (48%) had public insurance or were self pay, 39% had private non-HMO insurance, and 13% had HMO insurance (Table 1).

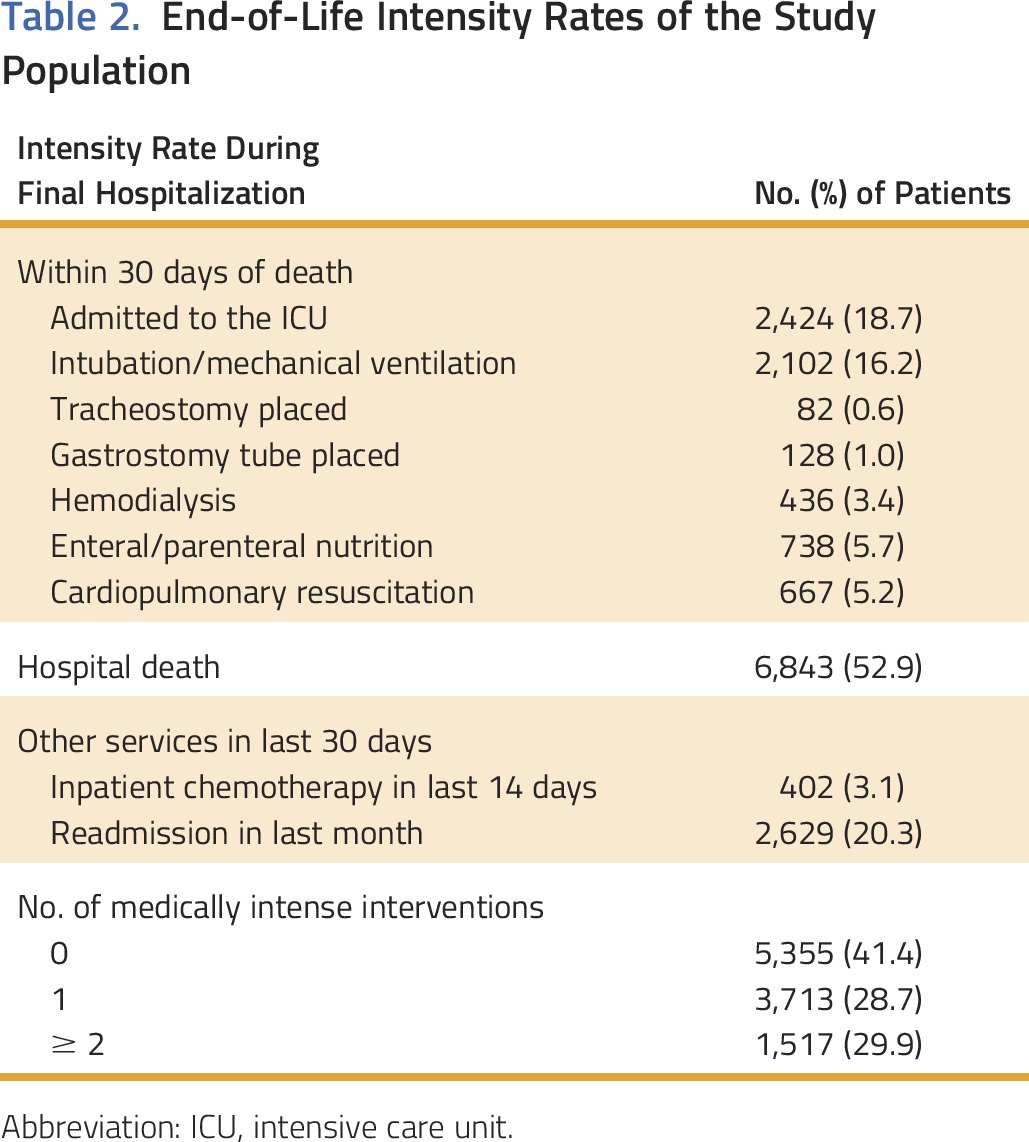

Intensity of End-of-Life Care

More than half of the patients (59%) received at least one inpatient high-intensity end-of-life intervention, and 30% received two or more (Table 2). The most prevalent intense interventions were hospital death (53%), readmission (20%), and ICU admission (19%).

Table 2.

End-of-Life Intensity Rates of the Study Population

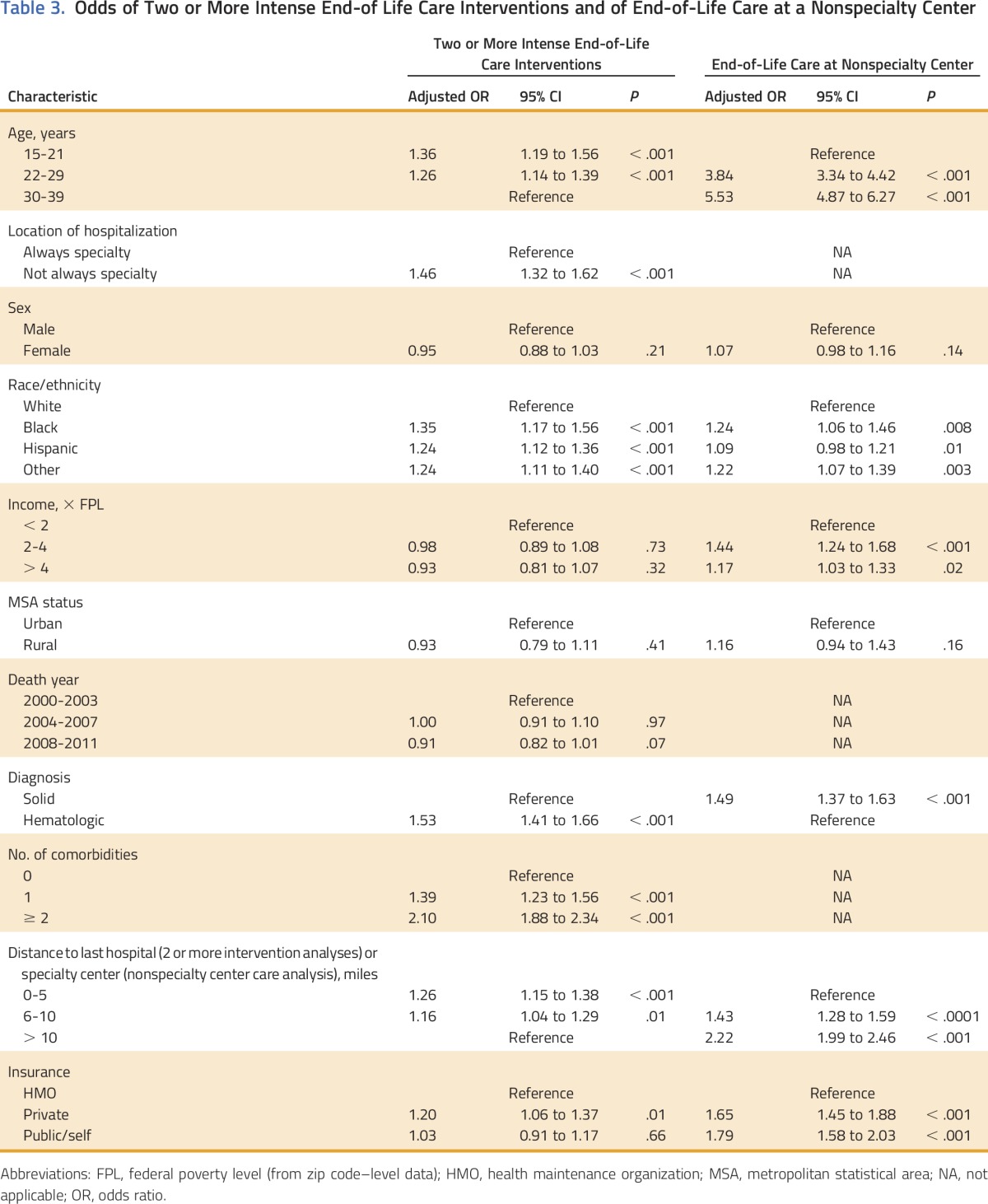

Factors Associated With High-Intensity End-of-Life Care

Receipt of two or more intense end-of-life interventions was associated with admission at a nonspecialty center even once in the last 6 months of life (OR, 1.46; 95% CI, 1.32 to 1.62; reference: only SC admission) and with hematologic malignancies (OR, 1.53; 95% CI, 1.41 to 1.66; reference: solid tumors). Those with minority race/ethnicity status of non-Hispanic black (OR, 1.35; 95% CI, 1.17 to 1.56), Hispanic (OR, 1.24; 95% CI, 1.12 to 1.36), or other race/ethnicity (OR, 1.24; 95% CI, 1.11 to 1.40; reference for all: non-Hispanic white) and with private non-HMO insurance (OR, 1.20; 95% CI, 1.06 to 1.37; reference: HMO insurance) also were more likely to have two or more intense interventions. Finally, younger patients age 15 21 years (OR, 1.36; 95% CI, 1.19 to 1.56) and 22 to 29 years (OR, 1.26; 95% CI, 1.14 to 1.39; reference for both: 30 to 39 years) were more likely to have two or more intense interventions, as were those who lived less than 10 miles from the final hospital (0 to 5 miles OR, 1.26 [95% CI, 1.15 to 1.38]; 6 to 10 miles OR, 1.16 [95% CI, 1.04 to 1.29]; reference: residence more than 10 miles from hospital; Table 3). The sensitivity analysis that used intubation or mechanical ventilation and ICU admission as a single intensity marker rather than two showed similar findings (data not shown). A significant interaction was observed between SC and age (P < .001). In particular, at nonspecialty centers, the younger the patient, the more likely they were to receive intense care, whereas, at specialty centers, 22 to 29 year olds had the highest odds of intense care.

Table 3.

Odds of Two or More Intense End-of Life Care Interventions and of End-of-Life Care at a Nonspecialty Center

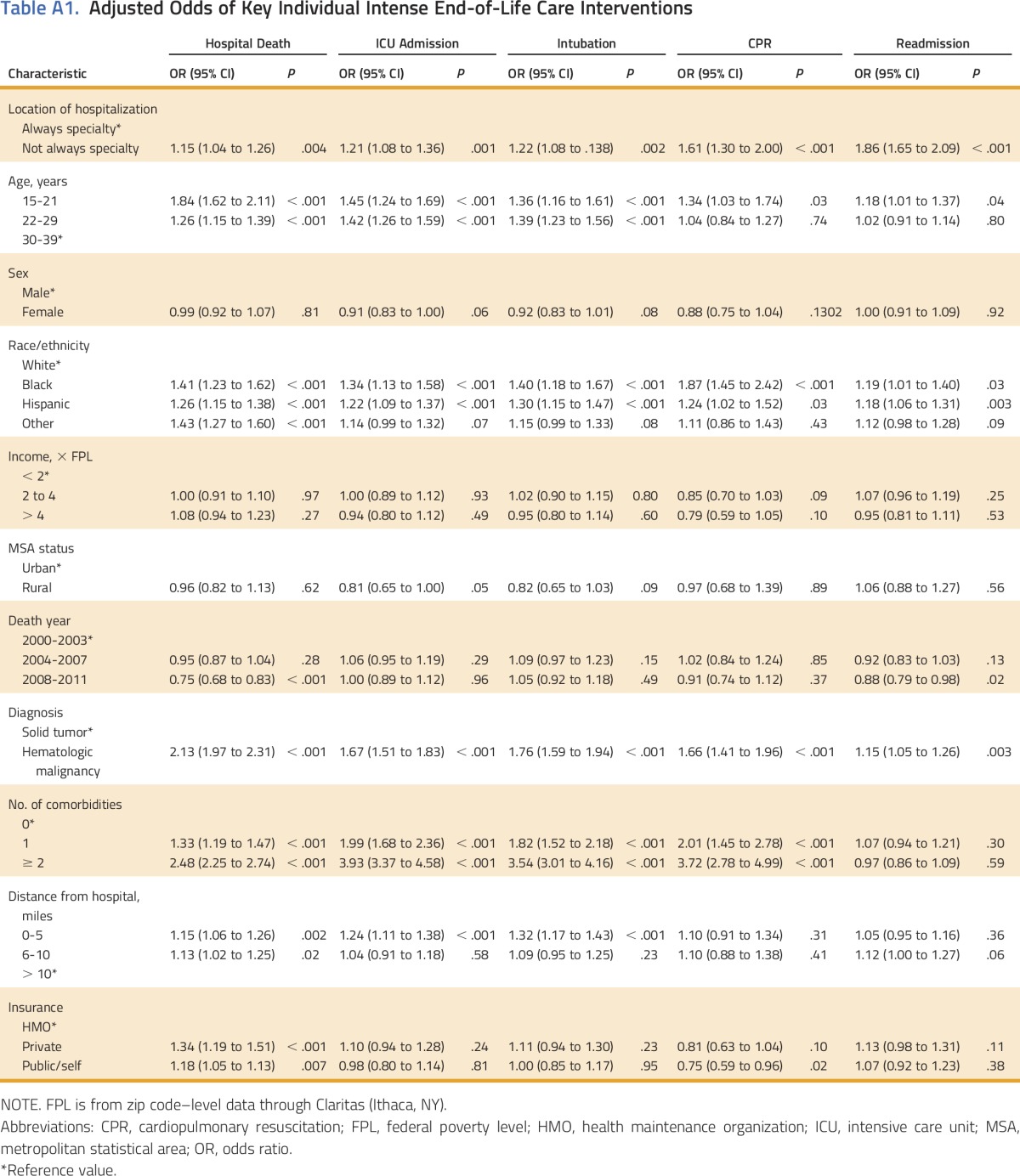

In separate regression models for hospital death, ICU admission, intubation, CPR, and readmission, the associations with receipt of the individual interventions were similar for the receipt of two or more intense interventions. In particular, those interventions were associated with nonspecialty center admission, younger age, minority race/ethnicity, hematologic diagnosis, and proximity to last hospital (Appendix Table A1, online only).

Factors Associated With Location of End-of-Life Care

Compared with patients who received their end-of-life care in SCs, patients who received their end-of-life care in nonspecialty care hospitals were more likely to reside greater than 5 miles from an SC (6 to 10 miles OR, 2.17 [95% CI, 1.95 to 2.40]; > 10 miles OR, 2.22 [95% CI, 2.0 to 2.46; reference for both: 0 to 5 miles) and in a lower-income county (< 2 × FPL OR, 1.44 [95% CI, 1.24 to 1.68]; 2 to 4 × FPL OR, 1.17 [95% CI, 1.03 to 1.33]; reference for both: > 4 × FPL). Patients at nonspecialty centers were more likely to have non-HMO private insurance (OR, 1.65; 95% CI, 1.45 to 1.88) or public insurance/self pay (OR, 1.79; 95% CI, 1.58 to 2.03; reference for both: HMO insurance) and to have black (OR, 1.24; 95% CI, 1.06 to 1.46) and other racial/ethnic identities (OR, 1.22; 95% CI, 1.07 to 13.9; reference for both: non-Hispanic white). Patients at nonspecialty centers also were more likely to be older (22 to 30 years OR, 3.84; [95% CI, 3.34 to 4.42]; ≥ 31 years OR, 5.53 [95% CI, 4.87 to 6.27]; reference for both: 15 to 21 years) and to have solid tumors (OR, 1.49; 95% CI, 1.37 to 1.63; reference: hematologic malignancies; Table 3).

Of the patients who had an in-hospital death, patients with an ICU admission during the terminal admission differed significantly from those without an ICU admission. Age at death, treatment center, sex, race/ethnicity, metropolitan statistical area, death year, diagnosis, comorbidity, and distance from hospital all were significantly different between the two groups (Table 1).

DISCUSSION

In this population-based study, the majority (59%) of AYA cancer decedents received at least one intense end-of-life care intervention, and nearly a third (30%) received two or more interventions. Nonspecialty centers were more likely than SCs to deliver high-intensity end-of-life care. High-intensity end-of-life care also was more common among AYAs who died at younger ages, those with an ethnic minority identity, and those with hematologic malignancies. The observed prevalence of intense end-of-life care among AYAs with cancer (59%) was slightly lower than in previous studies (68% and 75%).8,9 This difference could be explained by differences in definitions or study sampling. In the HMO study, the composite definition of end-of-life care intensity included emergency department use and admission in the last month (instead of readmission) but not hospital death.8 The prevalence of individual intensity markers is more consistent: the rate of ICU admissions in this study (19%), for example, was comparable to that observed in previous studies (21% to 22%).8,9 The prevalence of high-intensity care in this study’s population was higher than in the Medicare population: 53% of this population died in the hospital versus 29% to 30% of Medicare patients; 18% of this population was readmitted in the last 30 days versus 9% to 10% of Medicare patients.25,26 Because younger age was associated with increased intensity, these differences are unsurprising. However, whether this difference is goal concurrent and appropriate or does not respect patient wishes is unknown.

There is variation in intensity of end-of-life care for AYA oncology patients; specifically, administration of such care was more frequent in nonspecialty centers. The association is particularly interesting, because AYA oncology patients are less likely than their younger peers to be treated at SCs.10-12 This is a timely issue as the Affordable Care Act (ACA) is reconsidered: currently, 41% of ACA networks lack an NCI-designated cancer center, which may limit SC access for many patients.27 If the ACA Medicaid expansion ends, even fewer patients may have SC access, because public insurance/self pay is associated with nonspecialty center end-of-life use. Older patients, certain minorities, those with solid tumors, those with non-HMO insurance, those living further from SCs, and those in lower-income counties were more likely to be hospitalized at nonspecialty centers. Interestingly, blacks, but not Hispanics, were more likely to be hospitalized at nonspecialty centers. To our knowledge, this is the first time a nuanced understanding of the variation in SC use at the end of life is described in the literature.

We identified additional subgroups with higher rates of intense end-of life care, including younger patients, minorities, those with hematologic malignancies, and those living closer to the hospital. Similar disparities were found in several studies not conducted in AYA populations, mainly in the Medicare population and internationally.25,26,28-30 These associations held true when intubation and or mechanical ventilation plus ICU admission were counted as one intensity marker. This adds to previous AYA studies, which found that high-intensity care was associated with Asian ethnicity, advanced cancer diagnosis, discontinuous Medicaid enrollment, and higher family income in addition to the broader findings in this study of diagnosis, race/ethnicity, and age.8,9 These differences are unsurprising, because this study has a 10-fold larger study population than previous AYA studies, which provided more power to detect differences between groups and a more diverse population than studies limited to a certain geographic area or insurance status or to insurance continuity.8,9

Our findings may carry important implications for health care financing and health disparities. Improvements in end-of-life care may help reduce overall health care costs. End-of-life care accounts for approximately 25% of Medicare spending, and there is growing evidence that patients do not desire intense end-of-life care, which may be harmful.31-33 The majority of older adults who know they are dying do not want life-extending measures.34,35 Among the adult caregivers of dying patients, more intense end-of-life care is associated with worse outcomes (eg, major depressive disorders, post-traumatic stress disorder).36,37 Less is known about the impact of intense end-of-life care on AYA patients and their families, but one study of 17 adolescent oncology patients showed that 94% would want to die at home and that 88% would want a natural death.38 Reduction of end-of-life care intensity for these AYA patients may improve care quality and reduce health care costs.

Like any population-level study, this study has limitations to consider. The population-based study is limited to patients from California, but 10% of the US population resides in California and California is diverse, so it can shed light on national trends.21 This study was restricted to patients in the linked death certificate patient discharge database. Therefore, patients who were not admitted at any point in their lives; those only admitted at prison, Veterans Affairs, or out-of-state hospitals; or patients without record linkage numbers, were missed. If many patients were never hospitalized, this study would be biased toward more intensity. There are 2,777 AYA oncology patients in the death certificate database who are without a record linkage number, because they were never admitted at a qualifying hospital, had never been admitted anywhere, or were admitted but had no linkage number. However, 44% of the 2,777 unlinked patients died in the hospital (compared with 53% in the study population). Therefore, the population in the linked database and the patients without a record linkage number seem to have comparable rates of the one intensity marker compared with the linked and unlinked patients. Some end-of-life intensity studies restrict themselves to patients who have known terminal diagnoses (ie, stage IV diagnosis or relapse) to exclude patients who may receive intense interventions as a result of a sudden event, like sepsis, from which patients have a good chance of recovery. However, staging and relapse information is not available in OSHPD. The rates described here are consistent with (and actually more conservative than) the previous, smaller AYA studies.8,9 In addition, diagnosis age could not be determined in OSHPD. OSHPD has linked death certificates and final hospital admission for 2000 to 2011, but it has not yet linked more recent years. Therefore, this study does not reflect recent changes such as increased immunotherapy and the ACA. Other important end-of-life markers—hospice use and emergency department use in the last month—are not available in sufficient detail in the OSHPD database. There is a need for a robust hospice marker in this population, because some hospice agencies will not take a patient younger than a certain age. Therefore, the number of hospice agencies or hospice patients served in the local area may not be appropriate for this age group. Instead, this study focuses on inpatient care, and there may be different ethical implications and drivers for inpatient (eg, CPR, hospital death) versus outpatient (eg, emergency department visits) intensity. Therefore, inpatient and outpatient intensity each deserve individual attention.16-18 This study has the advantage of being a full population study with diverse insurers, which allows for an overall assessment of intensity rates and disparities in intensity of end-of-life care.

In conclusion, this population-based study finds that almost two thirds of AYA cancer decedents received intense end-of-life care and that younger patients, blacks, patients with hematologic malignancies, those with non-HMO insurance, and those hospitalized at nonspecialty centers are more likely to receive intense end-of-life care. It will be important to understand the underlying reasons for the association of these clinical and demographic characteristics with high-intensity care. It also will be particularly important to monitor how rates of intensity and SC access change with potential changes in US insurance policy.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We thank the Stanford Center for Policy, Outcomes, and Prevention for the provision of data access, programming, and statistical support. Supported by a KL2 Mentored Career Development Award of the Stanford Clinical and Translational Science Award to Spectrum (National Institutes of Health Awards No. KL2 TR 001083 and UL1 TR 001085) through salary support for E.J. Presented at the Annual Meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO), Chicago, IL, June 3-7, 2016, and at the ASCO Palliative Care in Oncology Symposium, San Francisco, CA, September 9-10, 2016.

Appendix

Table A1.

Adjusted Odds of Key Individual Intense End-of-Life Care Interventions

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conception and design: Emily E. Johnston, Lee Sanders, Smita Bhatia, Lisa J. Chamberlain

Financial support: Emily E. Johnston, Lee Sanders

Provision of study materials or patients: Lee Sanders

Collection and assembly of data: Emily E. Johnston, Elysia Alvarez, Olga Saynina

Data analysis and interpretation: All authors

Manuscript writing: All authors

Final approval of manuscript: All authors

Accountable for all aspects of the work: All authors

AUTHORS' DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

End-of-Life Intensity for Adolescents and Young Adults with Cancer: A Californian Population-Based Study That Shows Disparities

The following represents disclosure information provided by authors of this manuscript. All relationships are considered compensated. Relationships are self-held unless noted. I = Immediate Family Member, Inst = My Institution. Relationships may not relate to the subject matter of this manuscript. For more information about ASCO's conflict of interest policy, please refer to www.asco.org/rwc or ascopubs.org/journal/jop/site/misc/ifc.xhtml.

Emily E. Johnston

No relationship to disclose

Elysia Alvarez

No relationship to disclose

Olga Saynina

No relationship to disclose

Lee Sanders

No relationship to disclose

Smita Bhatia

No relationship to disclose

Lisa J. Chamberlain

No relationship to disclose

REFERENCES

- 1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Ten leading causes of death and injury. http://www.cdc.gov/injury/wisqars/leadingcauses.html.

- 2.Bleyer A: The death burden and end-of-life care intensity among adolescent and young adult patients with cancer. JAMA Oncol 1:579-580, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Institute of Medicine: When children die: Improving palliative and end-of-life care for children and their families. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK216211/

- 4.Smith TJ, Temin S, Alesi ER, et al. : American Society of Clinical Oncology provisional clinical opinion: The integration of palliative care into standard oncology care. J Clin Oncol 30:880-887, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Section on Hospice and Palliative Medicine and Committee on Hospital Care : Pediatric palliative care and hospice care commitments, guidelines, and recommendations. Pediatrics 132:966-972, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. National Quality Forum: Home. http://www.qualityforum.org/Home.aspx.

- 7.Dying in America : Improving Quality and Honoring Individual Preferences Near the End of Life. Washington, DC, The National Academies Press, 2014 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mack JW, Chen LH, Cannavale K, et al. : End-of-life care intensity among adolescent and young adult patients with cancer in Kaiser Permanente Southern California. JAMA Oncol 1:592-600, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mack JW, Chen K, Boscoe FP, et al. : High intensity of end-of-life care among adolescent and young adult cancer patients in the New York State Medicaid program. Med Care 53:1018-1026, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Albritton KH, Wiggins CH, Nelson HE, et al. : Site of oncologic specialty care for older adolescents in Utah. J Clin Oncol 25:4616-4621, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chamberlain LJ, Pineda N, Winestone L, et al. : Increased utilization of pediatric specialty care: A population study of pediatric oncology inpatients in California. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol 36:99-107, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Howell DL, Ward KC, Austin HD, et al. : Access to pediatric cancer care by age, race, and diagnosis, and outcomes of cancer treatment in pediatric and adolescent patients in the state of Georgia. J Clin Oncol 25:4610-4615, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Benchimol EI, Smeeth L, Guttmann A, et al. : The reporting of studies conducted using observational routinely-collected health data (RECORD) statement. PLoS Med 12:e1001885, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project: Clinical classification software: Diagnosis (January 1980 through September 2015). https://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/toolssoftware/ccs/AppendixASingleDX.txt.

- 15. National Cancer Institute: AYA site recode/WHO 2008 definition. https://seer.cancer.gov/ayarecode/aya-who2008.html.

- 16.Barnato AE, Farrell MH, Chang C-CH, et al. : Development and validation of hospital “end-of-life” treatment intensity measures. Med Care 47:1098-1105, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Earle CC, Park ER, Lai B, et al. : Identifying potential indicators of the quality of end-of-life cancer care from administrative data. J Clin Oncol 21:1133-1138, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Earle CC, Neville BA, Landrum MB, et al. : Evaluating claims-based indicators of the intensity of end-of-life cancer care. Int J Qual Health Care 17:505-509, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.National Quality Forum : Quality positioning system. http://www.qualityforum.org/QPS/QPSTool.aspx#qpsPageState

- 20.US Department of Health and Human Services : 2004 HHS poverty guidelines. http://aspe.hhs.gov/2004-hhs-poverty-guidelines

- 21.US Census Bureau : US census data. http://www.census.gov/data.html

- 22.Elixhauser A, Steiner C, Harris DR, et al. : Comorbidity measures for use with administrative data. Med Care 36:8-27, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Quan H, Sundararajan V, Halfon P, et al. : Coding algorithms for defining comorbidities in ICD-9-CM and ICD-10 administrative data. Med Care 43:1130-1139, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.van Walraven C, Austin PC, Jennings A, et al. : A modification of the Elixhauser comorbidity measures into a point system for hospital death using administrative data. Med Care 47:626-633, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Earle CC, Neville BA, Landrum MB, et al. : Trends in the aggressiveness of cancer care near the end of life. J Clin Oncol 22:315-321, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Miesfeldt S, Murray K, Lucas L, et al. : Association of age, gender, and race with intensity of end-of-life care for Medicare beneficiaries with cancer. J Palliat Med 15:548-554, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Kehl KL, Liao, K-P, Krause TM, et al: Access to accredited cancer hospitals within federal exchange plans under the Affordable Care Act. J Clin Oncol 35:645-651, 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 28.Sharma RK, Prigerson HG, Penedo FJ, et al. : Male-female patient differences in the association between end-of-life discussions and receipt of intensive care near death. Cancer 121:2814-2820, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ho TH, Barbera L, Saskin R, et al. : Trends in the aggressiveness of end-of-life cancer care in the universal health care system of Ontario, Canada. J Clin Oncol 29:1587-1591, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Guadagnolo BA, Liao K-P, Giordano SH, et al. : Variation in intensity and costs of care by payer and race for patients dying of cancer in Texas: An analysis of registry-linked Medicaid, Medicare, and dually eligible claims data. Med Care 53:591-598, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yabroff KR, Warren JL, Brown ML: Costs of cancer care in the USA: A descriptive review. Nat Clin Pract Oncol 4:643-656, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Emanuel EJ, Ash A, Yu W, et al. : Managed care, hospice use, site of death, and medical expenditures in the last year of life. Arch Intern Med 162:1722-1728, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Riley GF, Lubitz JD: Long-term trends in Medicare payments in the last year of life. Health Serv Res 45:565-576, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Weeks JC, Cook EF, O’Day SJ, et al. : Relationship between cancer patients’ predictions of prognosis and their treatment preferences. JAMA 279:1709-1714, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.McCarthy EP, Phillips RS, Zhong Z, et al. : Dying with cancer: Patients’ function, symptoms, and care preferences as death approaches. J Am Geriatr Soc 48:S110-S121, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wright AA, Zhang B, Ray A, et al. : Associations between end-of-life discussions, patient mental health, medical care near death, and caregiver bereavement adjustment. JAMA 300:1665-1673, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wright AA, Keating NL, Balboni TA, et al. : Place of death: Correlations with quality of life of patients with cancer and predictors of bereaved caregivers’ mental health. J Clin Oncol 28:4457-4464, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jacobs S, Perez J, Cheng YI, et al. : Adolescent end of life preferences and congruence with their parents’ preferences: Results of a survey of adolescents with cancer. Pediatr Blood Cancer 62:710-714, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]