Abstract

Unlike what is widely anticipated by the public, herbal medicines are not always safe despite being natural. We describe a 65-year-old Chinese man taking a prolonged maintenance dose of warfarin who experienced an elevated international normalized ratio (INR) with associated bleeding after drinking Gouqizi (goji berry) wine. This report illustrates that large doses (more than 6–12 g) of Gouqizi can significantly enhance the anticoagulant action of warfarin and may cause similar adverse effects in keeping with three previous reports. Therefore, the use of herbal medicines must adhere to pharmacopoeia-recommended guidelines, including dosage regimes. Doctors should advise patients regarding possible interactions between herbs and warfarin when prescribing and should increase the frequency of INR monitoring for those patients concurrently receiving warfarin and medicinal herbs. Further study is needed to do for the mechanism of interaction between Gouqizi and warfarin.

Keywords: Warfarin, Gouqizi, Lycium barbarum L., Drug–herb interactions, TCM

Warfarin is the most commonly used oral anticoagulant prescribed for patients with prosthetic heart valves, atrial fibrillation, pulmonary embolism and venous thrombosis [5]. The use of warfarin introduces challenges not only because it is known to have a narrow therapeutic range and risk of bleeding, but also because there are patient variables and potential drug–drug, drug–food and drug–herb interactions that can complicate its management [16]. The dosage of warfarin must be adjusted according to the international normalized ratio (INR) and patients are treated to obtain certain target INR ranges [5]. If the INR is lower than the target INR, there is the risk of thrombosis; however, if the INR is higher than the target INR, there is a high risk of bleeding. Consequently, in hospital patients are closely monitored and the risk of bleeding and thrombosis are considered, allowing the dose of warfarin to be adjusted as necessary. However, when patients are discharged from hospital, there is an increased risk that they may take other medicines and/or herbs, possibly prescribed by another doctor, and that their diet may change, resulting in an increased risk of bleeding or thrombosis due to interactions between warfarin and herbs or foodstuffs.

In China, traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) is popular for the treatment of minor ailments, such as colds or fevers, and herbs are often prescribed to patients by TCM practitioners. In the case of more serious conditions, patients generally combine TCM with Western medicine. In addition, culinary herbs are typically consumed seasonally in order to maintain good health. Taking into account all of the above, it may be considered that there is an increased risk of drug–herb interactions in patients consuming culinary herbs for medicinal purposes or those taking TCMs, which may lead to the enhanced or reduced effect of warfarin, possibly leading to bleeding or thrombosis.

TCMs, such as Danshen [3], Ginkgo biloba and Dong quai [4] have been reported to enhance the anticoagulation activity of warfarin, while Panax ginseng [4] has been reported to impede its action.

Lycium barbarum L., also known as goji berry and widely used in food (6–12 g daily) and herbal medicine(6–12 g daily), is defined in the Chinese Pharmacopoeia as Gouqizi. It belongs to the Solanaceae family and, typically, the dried ripe fruit of Lycium barbarum L. (Ningxia gouqi) are harvested from summer to autumn (Chinese Pharmacopoeia, Fig. 1). Polysaccharides represent quantitatively the most important group of substances in Lycium barbarum L. [12].

Fig. 1.

Lycium barbarum L., also known as goji berry and widely used in food and herbal medicine, is defined in the Chinese Pharmacopoeia as Gouqizi.

Gouqizi is used in TCM as a mild Yin tonic, enriching Yin in the liver and kidneys whilst moistening lung Yin. Clinical manifestations derived from Yin deficiencies include blurred vision and diminished visual perception, infertility, abdominal pain, dry cough, fatigue and headaches [12]. Gouqizi is also a popular ingredient in Chinese herbal cuisine and is consumed in soups and porridge, as well as with seafood, meat and vegetables. For its health benefits, Gouqizi is traditionally consumed in the form of tea, juice or wine in China.

To date, three articles focused on the interaction between Gouqizi and warfarin have been published: two case reports from America [13], [8] and one case from Hong Kong [9]. In these three cases, Gouqizi was ingested as a form of juice or tea. In both cases, patient's INR increased after consuming the juice or tea. In this case report, we provide additional evidence for the interaction between warfarin and Gouqizi contained in a wine product commonly sold in China.

1. Case report

A 65-year-old Chinese man with a history of prosthetic heart valve replacement had been stabilized on warfarin anticoagulation therapy for two years. He has no other medical conditions and his only medication was warfarin. The patient was compliant regarding the attendance of appointments and in taking the medication, and maintained a therapeutic INR (1.7–2.5) on a maintenance daily dose of 1.875 mg warfarin with monthly INR monitoring. The patient did not exhibit symptoms of ecchymosis, nosebleeds, bleeding gums or blood clots and denied drinking and smoking.

On the morning of November 10, 2013, the patient developed macroscopic hematuria and consequently attended hospital. The urine test results confirmed hematuria with an abnormal urinary red blood cell count of 33201.5/μl (the normal range is 0–23/μl) and an INR of 3.84. The patient did not report any change in the state of his condition and denied taking any additional medication or a change in diet or lifestyle; however, he indicated that he had consumed 20 ml of Gouqizi wine in the evening on November 9 on the advice of a friend as he was suffering from blurred vision. Although the patient was aware that the wine could influence the therapeutic effect of warfarin, he had previously consumed 60 ml of wine (not containing Gouqizi) and not experienced any negative effects.

Application of the Naranjo Adverse Drug Reaction (ADR) Scale [11] indicated a probable relationship (score of 6) between the elevated INR with hematuria and the patient’s concomitant use of warfarin and Gouqizi. The patient was advised to discontinue the use of Gouqizi wine and to abstain from warfarin for 2 days. On the morning of November 11, the patient continued to see blood in the urine, with diminished color intensity; by the evening, the hematuria had resolved. On November 12, the patient's INR was 2.12 and urine test results were normal with a urinary red blood cell count of 11/μl. He continued warfarin at a daily dose of 1.875 mg and the INR was found to be 2.0 after 1 week (Table 2).

Table 2.

INR vs warfarin dose (mg) before and after consumption of Gouqizi wine.

| 16-Jul-2013 | 19-Aug-2013 | 17-Sept-2013 | 16-Oct-2013 | 10-Nov-2013 | 11-Nov-2013 | 12-Nov-2013 | 19-Nov- 2013 |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| INR | 2.11 | 2.1 | 1.91 | 2.46 | 3.84 | – | 2.12 | 2.0 |

| Warfarin (mg) | 1.875 | 1.875 | 1.875 | 1.875 | – | – | 1.875 | 1.875 |

2. Discussion

Gouqizi is a highly nutritional fruit, which has been used for more than 2000 years in China for the prevention and treatment of disease as part of TCM with early records dating back to the Tang Dynasty (1000–1400 AD) [2]. TCM uses both the fruit and root bark of Lycium barbarum L., where the fruit (Gouqizi) is used to tonify Yin, while the root bark (Digupi) is used to “clean” the heart. Nowadays, Gouqizi is widely used for its anti-aging properties and as a health food worldwide. It is thought to play an important role in preventing and treating various chronic diseases, such as diabetes, hyperlipidemia, thrombosis, immunodeficiency, cancer, hepatitis and male infertility [6]. Previously, Amagase et al. [1] showed that Gouqizi has a high nutrient value and contains high levels of antioxidants, with 68% carbohydrate, 12% protein, 10% fiber and 10% fat.

In this case report, the Naranjo ADR score of 6 showed that the patient's elevated INR and related bleeding may be due to an interaction between warfarin and Gouqizi wine. Karlson et al. [7] previously showed that administration of 375 ml wine did not result in thrombin times (TTs) outside the therapeutic range, which suggested that a moderate intake of alcohol occasionally may be acceptable during anticoagulant therapy. In this case, the patient had previously consumed 60 ml of wine without a negative effect, suggesting that the reported hematuria was not due to the alcohol content of the herbal wine. Furthermore, we eliminated the influence of another disease (such as fever, diarrhea, thyroid hyperfunction, etc.), other drugs (antibiotics, statins, amiodarone, etc.) or other herbs (Danshen, Ginkgo biloba, Dong quai, etc.). The patient did not report any changes to his lifestyle or diet. As such, we considered that Gouqizi may have enhanced the effect of warfarin, thus leading to the occurrence of hematuria.

In China, Gouqizi is a popular component of the daily diet, making the prohibition of its consumption in patients taking warfarin difficult to implement. It should be noted that the previous published cases reporting adverse interactions between Gouqizi and warfarin in Table 1 indicated that the dosages of Gouqizi taken by the patients were larger (case 1 is 72–96 OZ; case 2 is 50 g and 40 g; case 3 is 240 ml; case 4 is 20 ml) than that recommended by the Chinese Pharmacopoeia (6–12 g) (Pharmacopoeia of The People’s Republic of China, 2010). Furthermore, symptoms induced by the interaction between Gouqizi and warfarin can be managed by withholding warfarin or the use of vitamin K (Table 1). However, it is important to establish the dosage of Gouqizi that can enhance the effect of warfarin. The little study in Appendix A showed that 6 g of Gouqizi daily is a safe dose for patients taking warfarin.

Table 1.

Case reports describing interactions between warfarin and Gouqizi.

| Case | Location | Indication | Gouqizi form |

Gouqizi dose |

INR before Gouqizi |

INR after Gouqizic |

Treatment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lam and Elmer [8] | Seattle, WA, USA | AFa | Tea | 72∼96 oz | 2.5 | 4.1 | Warfarin withheld for 1 day |

| Leung et al. [9] | Hong Kong, China | AFa | Tea | 50 g | 3.0 | 4.97 | Warfarin withheld for 2 days |

| 40 g | 2.75 | 3.86 | Warfarin withheld for 2 days | ||||

| Rivera et al. [13] | Los Angeles, CA, USA | Knee surgery | Juice | 240 ml | No INR measured |

PT: 120 s with epistaxis, bruising and rectal bleeding | Phytonadione, 15 mg |

| Current case | Fujian, China | PHVb, AFa | Wine | 20 ml | 2.46 | 3.84 with hematuria | Warfarin withheld for 2 days |

AF: atrial fibrillation.

PHV: prosthetic heart valve.

Gouqizi: Lycium barbarum L. (also known as goji berry or Chinese wolfberry).

In China it is common to use Western medicine alongside TCM to treat disease and this may explain the increased risk of warfarin-induced bleeding in China compared to other countries [10]. Due to public concern regarding the risk of bleeding during treatment with warfarin, as well as the uneasy relationship between allopathic doctors and their patients, no more than 10% of patients with atrial fibrillation take warfarin in China [5]. Thus, we encourage the collection and publication of data focused on the interactions between TCMs and warfarin, as well as the consequential risk of bleeding or thrombosis, to promote the use of warfarin in Chinese patients and to better prevent thrombi. Such data may also alert doctors from all countries to the risk of warfarin-induced bleeding due to the effects of TCMs.

3. Conclusion

This case revealed that Gouqizi can enhance the anticoagulant effect of warfarin and may consequently cause bleeding. However, a daily Gouqizi dose of 6 g (dosing recommended by Chinese Pharmacopoeia) for 3 days did not enhance the effects of warfarin in three patients with prosthetic heart values who were concomitantly taking warfarin. Further study is needed to establish the dose of Gouqizi that can have an additive effect on the anticoagulant activity of warfarin. Pharmacists and doctors who manage anticoagulation clinics should pay particular attention to patients who take warfarin concomitantly with TCMs and INR monitoring should be increased in such patients. Furthermore, patients should be better educated with regards to the possible interactions between warfarin and herbal medicines.

Conflict of interests

There is no conflict of interests.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by grants from the Scientific Research Foundation for the Returned Overseas Chinese Scholars, State Education Ministry (No. 2015B001) and the Fujian Medical Innovation Project (No. 2014-CX-18).

Appendix A.

The interaction study of warfarin and Lycium barbarum L.

Methods

This project about the interaction study of warfarin and Lycium barbarum L. is approved by Fujian Medical University Union Hospital ethics committee (NO: 2015KY002). This study required patients who had taken warfarin for at least three monthes. Three patients with prosthetic heart valves were included in this study. The tea was made by boiling 6 g of Gouqizi in 3 cups of water and the volume was then concentrated to around 1 cups by simmering [9]. A starting INR was taken before taking Gouqizi, and then Gouqizi (6 g) was administered as a tea for three consecutive days, then the INR was taken in the fourth day.

Results and discussion

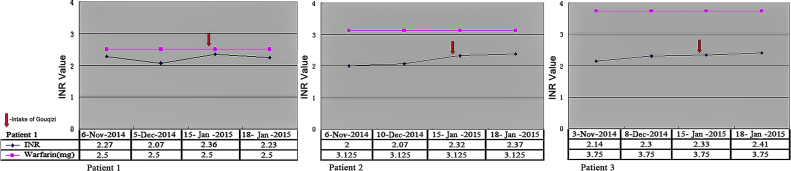

The results showed that, during the 3-day study period when the patients concurrently took warfarin (no other medication), a daily dose of 6 g (dosing recommended by Chinese Pharmacopoeia is 6–12 g daily) Gouqizi (total dose: 18 g) did not affect the INR, which remained within the target range (1.7–2.5) for all three patients (Fig. 2), suggesting that this may represent a safe dose. In these four cases in Table 1, the dosing of Gouqizi is larger (case 1 is 72–96 OZ; case 2 is 50 g and 40 g; case 3 is 240 ml; case 4 is 20 ml). So maybe it is safe for patients who take warfarin concomitantly with Gouqizi 6 g daily, and it is unsafe for patients who take warfarin concomitantly with Gouqizi more than 6 g daily. However, the limitations of this small study should be considered in the interpretation of these results as it was not convenient to collect the patients' blood samples for further determination of drug concentrations in the blood because the patients lived in various regions of the Fujian province. Thus, further research is needed to establish a safe dose of Gouqizi to use alongside warfarin treatment and to study the possible mechanism of interaction between Gouqizi and warfarin.

Fig. 2.

INR vs warfarin dose (mg) for three patients before and during treatment with Gouqizi (6 g/day) for 3 days. A starting INR was taken before taking Gouqizi on 15 January 2015 (the INR of patient 1 is 2.36, the INR of patient 2 is 2.32, the INR of patient 3 is 2.33), and then Gouqizi (6 g) tea was administered in the evening for three consecutive days (15–17 January 2015), then the INR was taken in the fourth day (18 January 2015, he INR of patient 1 is 2.23, the INR of patient 2 is 2.37, the INR of patient 3 is 2.41).

References

- 1.Amagase H., Sun B., Borek C. Lycium barbarum (goji) juice improves in vivo antioxidant biomarkers in serum of healthy adults. Nutr. Res. 2009;29:19–25. doi: 10.1016/j.nutres.2008.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Burke D.S., Smidt C.R., Vuong L.T. Momordica cochichinensis, Rosa roxburghii, wolfberry, and sea buckthorn—highly nutritional fruits supported by tradition and science. Curr. Top. Nutr. Res. 2005;3:259–266. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chan T.Y. Interaction between warfarin and danshen (Salvia miltiorrhiza) Annu. Pharmacother. 2001;35:501–504. doi: 10.1345/aph.19029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ge B., Zhang Z., Zuo Z. Updates on the clinical evidenced herb-warfarin interactions. Evid. Based Complement. Alternat. Med. 2014;362:1–18. doi: 10.1155/2014/957362. Article ID. 957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hu D., Sun Y. Epidemiology, risk factors for stroke, and management of atrial fibrillation in China. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2008;52:865–868. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.05.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jin M., Huang Q., Zhao K. Biological activities and potential health benefit effects of polysaccharides isolated from Lycium barbarum L. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2012;54:16–23. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2012.11.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Karlson B., Leijd B., Hellström K. On the influence of vitamin K-rich vegetables and wine on the effectiveness of warfarin treatment. Acta Med. Scand. 1986;220:347–350. doi: 10.1111/j.0954-6820.1986.tb02776.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lam A.Y., Elmer G.W., Mohutsky M.A. Possible interaction between warfarin and Lycium barbarum L. Annu. Pharmacother. 2001;35:1199–1201. doi: 10.1345/aph.1Z442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Leung H., Hung A., Hui A.C. Warfarin overdose due to the possible effects of Lycium barbarum L. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2008;46:1860–1862. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2008.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liu Y., Meng X., Chen B.T. Clinical results of the low intensity of oral anticoagulant therapy for patients with mechanical heart valve prostheses. Chin. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2001;17:263–265. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Naranjo C.A., Busto U., Sellers E.M. A method for estimating the probability of adverse drug reactions. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 1981;30:239–245. doi: 10.1038/clpt.1981.154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Potterat O. Goji (Lycium barbarum and L. chinense): phytochemistry, pharmacology and safety in the perspective of traditional uses and recent popularity. Planta Med. 2010;76:7–19. doi: 10.1055/s-0029-1186218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rivera C.A., Ferro C.L., Bursua A.J., Gerber B.S. Probable interaction between Lycium barbarum (goji) and warfarin. Pharmacotherapy. 2012;32:50–53. doi: 10.1002/j.1875-9114.2012.01018.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhang J.H., Liu M.B., Guan C.F. Establishment and practice of online anticoagulation clinic. Chin. Pharm. J. 2014;49:1476–1478. [Google Scholar]