Abstract

Background:

Entecavir (ETV) has been shown to be effective in randomized controlled trials in highly selected patients with hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection. This study aimed to evaluate the efficacy of ETV in chronic hepatitis B (CHB) patients in the real-world setting.

Methods:

A total of 233 treatment-naïve, CHB patients who received at least 12 months of ETV treatment were included in this retrospective study. Rates of virological response (VR), hepatitis B s antigen (HBsAg) loss, hepatitis B e antigen (HBeAg) clearance/seroconversion, virological breakthrough, cirrhosis, and hepatocellular carcinoma were evaluated.

Results:

Of 233 patients, 175 patients were male, with mean age of 43 years old, and 135 patients were HBeAg positive. The mean baseline levels of serum alanine aminotransferase and HBV DNA in all patients were 230 U/L and 6.6 log 10 IU/ml, respectively. The mean follow-up period was 28 months. The cumulative rates of achieving VR increased from 3.4% at 3 months to 94.4% at 60 months. Primary nonresponse occurred in 3 (1.3%) patients. Partial VR (PVR) occurred in 61 (26.2%) patients at 12 months. The baseline serum HBV DNA level (hazard ratio [HR], 2.054; P < 0.001) was an independent risk factor for PVR. HBsAg loss did not occur. The cumulative rates of HBeAg clearance increased from 2.2% at 3 months to 28.2% at 60 months. PVR was the significant determinant of HBeAg clearance (HR, 0.341; P = 0.026). Age (HR, 1.072; P = 0.013) and PVR (HR, 5.131; P = 0.017) were the significant determinants of cirrhosis.

Conclusions:

ETV treatment was effective for HBV DNA suppression in this study, but HBsAg loss and HBeAg clearance/seroconversion rates were lower compared with previous clinical trials. PVR was associated with HBeAg clearance and cirrhosis.

Keywords: Entecavir, Hepatitis B Virus, Partial Virological Response, Primary Nonresponse, Real-world, Virological Response

INTRODUCTION

Despite the availability of highly effective vaccines was over 20 years, hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection is still the major cause of liver-related morbidity and mortality in China. Importantly, the HBV infection in China is usually acquired perinatally,[1] making for a prolonged immune tolerance phase and an immune clearance phase, the latter is associated with a higher risk of chronic hepatitis B (CHB)-related cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC).[2] It has been well established that the risk of disease progression is reduced through the sustained suppression of HBV DNA to undetectable levels.[2,3,4] Several nucleos (t) ide analogs (NAs) have been approved for the treatment of CHB.[2] Due to their high efficacy and low risk of antiviral resistance, entecavir (ETV) and tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (TDF) are recommended as first-line treatment by clinical practice guidelines.[5,6,7]

ETV is highly effective at suppressing HBV DNA replication to undetectable levels. In the study ETV-901, long-term treatment with ETV achieved durable and increasing viral suppression, with undetectable HBV DNA (<300 copies/ml) being achieved in 94% of hepatitis B e antigen (HBeAg) positive patients after over 5 years of therapy and in 95% of HBeAg negative patients after over 3 years of therapy.[8] Results also suggested that ETV was well tolerated[9] and the viral resistance rate was very low (1.2%) following up to 6 years of treatment.[10] Despite its efficacy, about 10–20% of patients treated with ETV showed a partial virological response (PVR).[11,12] These results have clearly demonstrated the efficacy of ETV in the controlled environment of randomized clinical studies. However, patients in real life often differ from those included in the registered studies. Patients in “real-world” clinical settings tend to be more heterogeneous, including patients with various comorbidities such as obesity, renal dysfunction, and diabetes. Co-factors such as alcohol intake and smoking, having direct impacts on fibrosis progression, may also be common. Moreover, patients in “real-world” clinical settings may be less likely to maintain good adherence. Therefore, there is a need for a real-world study to confirm the efficacy data reported in clinical studies. The aim of this study was to evaluate the efficacy of ETV in CHB patients in real-world settings in China.

METHODS

Ethical approval

As a retrospective study and data analysis were performed anonymously, this study was exempt from the ethical approval and informed consent from patients.

Study design and patient

In cooperation with the Society of Hepatology of the Chinese Medical Association, the Chinese Foundation for Hepatitis Prevention and Control built a liver disease research and clinical application data platform – the “China Registry of Hepatitis B” (CR-HepB), which included 38 top ranked hospitals in China. Patients were registered at each center by internal databases. A web-based electronic case report form was designed for CR-HepB. Demographic, clinical and laboratory data, HBV treatment history, and NA start date, dosing, and duration were recorded. All laboratory testing was obtained at the respective local laboratories in each center.

We collected the data from CR-HepB for this study in April 2016. The criteria for data collection included: (1) HepB surface antigen persisted for at least 6 months before the initial of treatment; (2) treatment naïve (no previous NAs or interferon), initially treated with ETV monotherapy; (3) virological response (VR) was defined as serum HBV DNA levels <20 IU/ml during the on-treatment follow-up period; (4) the ETV treatment was lasted for at least 12 months; (5) patients were regularly followed up at 3, 6, and 12 months after ETV treatment. The criteria for data exclusion: (1) patients who suffered from cirrhosis or HCC before ETV treatment; (2) patients who underwent liver transplantation before ETV treatment; (3) noncompliant patients; (4) patients who were not followed up regularly. In this study, the decision to initiate ETV treatment was at the discretion of the investigators from each center.

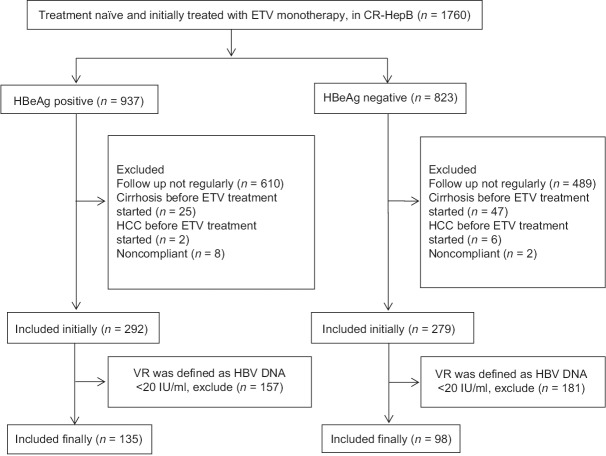

Until April 2016, total 1760 CHB patients (937 were HBeAg positive) were initially treated with ETV monotherapy, whereas 1189 patients were excluded: 1099 patients were not followed up regularly, 72 patients suffered cirrhosis before ETV treatment, 8 patients suffered HCC before ETV treatment, and 10 patients were noncompliant. The low limit of HBV DNA detection at each center varied between <20 IU/ml and <500 IU/ml. Because in the Asia Pacific Association of Study Liver Diseases (APASL) 2015 guideline, undetectable serum HBV DNA is defined as a serum HBV DNA level was below the detection limit (<12 IU/ml) based on a sensitive validated quantitative polymerase chain reaction (PCR)-based assay,[5] we defined VR as HBV DNA <20 IU/ml. In that case, 338 patients were excluded further. A total of 233 patients thus were eligible for our analysis. A flow chart of 233 patients enrolled in this study is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

A flow chart of patients selection.

In this study, we retrospectively reviewed data from 233 treatment-naïve CHB patients who received at least 12 months of ETV treatment between April 2007 and April 2015.

Definitions

All the definitions in our study were made according to the APASL guideline.[5] VR was defined as undetectable HBV DNA (HBV DNA <20 IU/ml) by a sensitive PCR assay during the treatment and follow-up period. Primary nonresponse (PNR) was defined as <1 log10 IU/ml decrease in HBV DNA level from baseline at 3 months of therapy. PVR was defined as a decrease in HBV DNA of more than 1 log10 IU/ml, but with detectable HBV DNA after at least 12 months of therapy in compliant patients. Virological breakthrough (VB) was defined as a confirmed increase in HBV DNA level of more than 1 log10 IU/ml compared to the nadir (lowest value) HBV DNA level on therapy (as confirmed 1 month later). HBeAg clearance was defined as loss of HBeAg in a patient who was previously HBeAg positive. HBeAg seroconversion was defined as loss of HBeAg and detection of anti-HBe in a patient who was previously HBeAg positive and anti-HBe negative.

Endpoints

Primary endpoints of this study included the cumulative incidence of VR, PNR, PVR, VB and hepatitis B s antigen (HBsAg) loss during the treatment period. Secondary endpoints were the cumulative incidence of HBeAg clearance and seroconversion (in HBeAg-positive patients). Tertiary endpoints were the incidence of newly developed cirrhosis and HCC.

Assay methodology

All patients were regularly followed at intervals of 3 or 6 months by routine laboratory assessment. Serum alanine aminotransferase (ALT), aspartate aminotransferase, bilirubin, and albumin levels were measured locally using automated techniques. HBsAg, anti-HBs, HBeAg, and anti-HBe were tested in all centers using commercially available immunoassay kits. Serum HBV DNA levels were measured using a quantitative real-time PCR. The lower limit of sensitivity of the assay is 20 IU/ml. HBV resistance testing was not uniformly conducted in this study, but the rates of VB were noted. Cirrhosis and HCC were monitored at each center at the discretion of the investigators.

Statistical analysis

HBV DNA levels were logarithmically transformed for analysis. Follow-up times were calculated from the date of ETV treatment initiation to the date of the event or the last date of follow-up or censorship. Continuous variables were expressed as the mean ± standard deviation (SD) or median (interquartile range) where appropriate. The cumulative rates were compared using Kaplan–Meier analysis and subsequent log-rank test. Cox's regression analysis was used to study which of the factors were associated with VR, PVR, HBeAg clearance, HBeAg seroconversion, and development of cirrhosis and HCC during the ETV treatment. The hazard ratio (HR) and 95% confidence interval (95% CI) were calculated to assess the relative risk confidence. All statistical tests were carried out by two-sided, and P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. SPSS version 16.0 was used for all statistical analyses (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

RESULTS

Baseline characteristics

Two hundred and thirty-three patients were followed at least 12 months after ETV treatment. The baseline characteristics are shown in Table 1: 175 (75.1%) patients were male with the mean age of 43 years old (SD, 11 years), and 135 (57.9%) patients were HBeAg positive. The mean baseline levels of serum ALT and HBV DNA were 230 U/L (SD, 172 U/L) and 6.6 log10 IU/ml (SD, 1.2 log10 IU/ml), respectively. The HBeAg-positive patients were younger than the HBeAg-negative patients. The baseline HBV DNA levels in the HBeAg-positive patients were higher than that in the HBeAg-negative patients. The mean follow-up period was 28 months (range, 12–60 months). We followed 233, 151, 102, 53, and 10 patients for 12, 24, 36, 48, and 60 months, respectively.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics and on-treatment characteristics of the study population

| Characteristics | All patients (n = 233) | HBeAg positive (n = 135) | HBeAg negative (n = 98) | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (year) | 43 ± 11 | 41 ± 11 | 47 ± 8 | <0.001 |

| Male, n (%) | 175 (75.1) | 101 (74.8) | 74 (75.5) | 0.904 |

| Baseline ALT (U/L) | 230 ± 172 | 235 ± 191 | 222 ± 142 | 0.590 |

| Baseline HBV DNA (log10 IU/ml) | 6.6 ± 1.2 | 7.0 ± 1.1 | 6.0 ± 1.0 | <0.001 |

| Follow-up (months), mean (range) | 28 (12–60) | 30 (12–60) | 24 (12–48) | 0.081 |

| PNR, n (%) | 3 (1.3) | 1 (0.1) | 2 (0.2) | 0.385 |

| PVR, n (%) | 61 (26.2) | 48 (35.6) | 13 (13.3) | <0.001 |

| VB, n (%) | 2 (1.9) | 2 (1.5) | 0 | 0.226 |

| Presence of cirrhosis, n (%) | 10 (4.3) | 6 (4.4) | 4 (4.1) | 0.893 |

| Presence of hepatology carcinoma, n (%) | 5 (2.1) | 3 (2.2) | 2 (2.0) | 0.925 |

HBeAg: Hepatitis B e antigen; ALT: Alanine aminotransferase; HBV: Hepatitis B virus; PVR: Partial virological response; PNR: Primary nonresponse; VB: Virological breakthrough.

Virological response

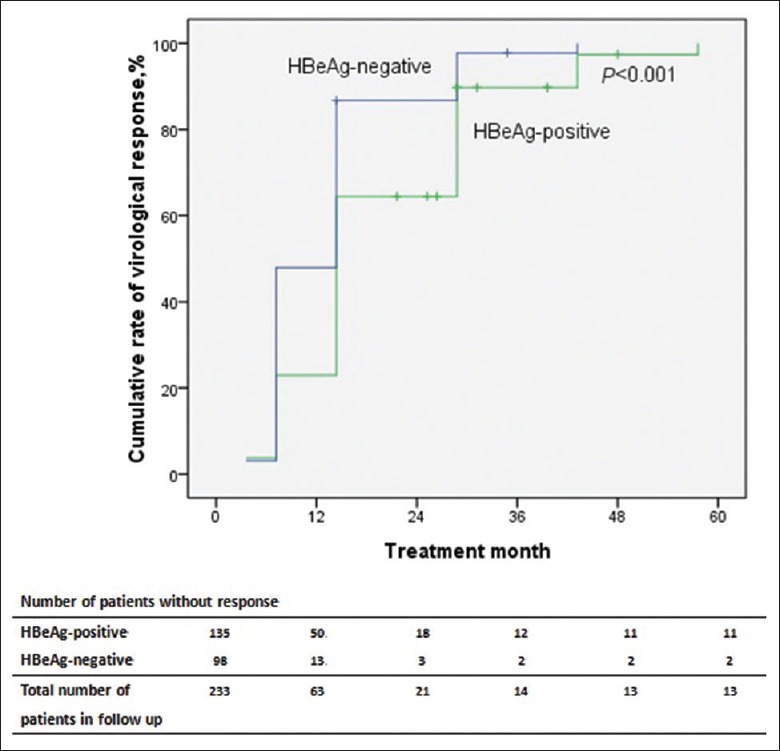

The cumulative rates of achieving VR at 3, 6, 12, 24, 48, and 60 months were 3.4%, 33.5%, 73.0%, 91.0%, 94.0%, 94.4%, and 94.4% in 233 patients, respectively. In HBeAg-positive patients (n = 135), the cumulative rates of achieving VR at 3, 6, 12, 24, 48, and 60 months were 3.7%, 23.0%, 63.0%, 86.7%, 91.1%, 91.9%, and 91.9%, respectively. In HBeAg-negative patients (n = 98), the cumulative rates of achieving VR at 3, 6, 12, 24, 48, and 60 months were 3.1%, 48.0%, 86.7%, 96.9%, 98.0%, 98.0%, and 98.0%, respectively. In the Kaplan–Meier analysis, there were significant differences in the cumulative rates of achieving VR between HBeAg-positive and HBeAg-negative patients [P < 0.001; Figure 2].

Figure 2.

Kaplan–Meier curve for the probability of achieving virological response for all patients according to HBeAg status at baseline. P value was determined using log-rank testing.

Primary nonresponse

PNR occurred in 3 (1.3%) patients. Among them, one HBeAg-positive patient and one HBeAg-negative patient were PVR at 12 months and achieved VR at 24 months. Another HBeAg-negative patient achieved VR at 12 months. None of them experienced VB. No patients were diagnosed with cirrhosis or HCC.

Partial virological response

PVR occurred in 61 (26.2%) patients, and 48 (78.7%) of PVR patients were HBeAg positive. The rate of PVR in HBeAg-positive patients was higher than that in HBeAg-negative patients (P < 0.001). Among the 61 PVR patients, 42 (68.9%), 7 (11.5%) and 1 (1.6%) achieved VR at 24, 36 and 48 months, respectively. There was no treatment adaptation after prolonged ETV therapy. However, 11 patients did not achieve VR at the end of the follow-up (range, 12–40 months). No patients experienced VB. The baseline serum HBV DNA level (HR, 2.054; 95% CI, 1.497–2.819; P < 0.001) was an independent risk factor for developing PVR [Table 2].

Table 2.

Factors associated with PVR* in ETV-treated patients

| Variable | Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI) | P | HR (95% CI) | P | |

| Age | 0.991 (0.965–1.018) | 0.521 | – | – |

| Male | 0.978 (0.497–1.926) | 0.949 | – | – |

| HBeAg positivity | 3.607 (1.824–7.134) | <0.001 | 1.933 (0.916–4.080) | 0.084 |

| Baseline HBV DNA (log10 IU/ml) | 2.263 (1.678–3.051) | <0.001 | 2.054 (1.497–2.819) | <0.001 |

| Baseline ALT (U/L) | 0.998 (0.996–1.000) | 0.099 | – | – |

| Baseline AST (U/L) | 1.000 (0.997–1.002) | 0.750 | – | – |

| PNR | 5.797 (0.516–65.098) | 0.154 | – | – |

| Baseline HBeAg | 1.000 (1.000–1.001) | 0.966 | – | – |

*Defined as >1 log decrease in serum HBV DNA level from baseline but a detectable load at 12 months of NA therapy. PVR: Partial virological response; ETV: Entecavir; HBeAg: Hepatitis B e antigen; HBV: Hepatitis B virus; ALT: Alanine aminotransferase; AST: Aspartate aminotransferase; HR: Hazard ratio; CI: Confidence interval; NA: Not available; PNR: Primary nonresponse.

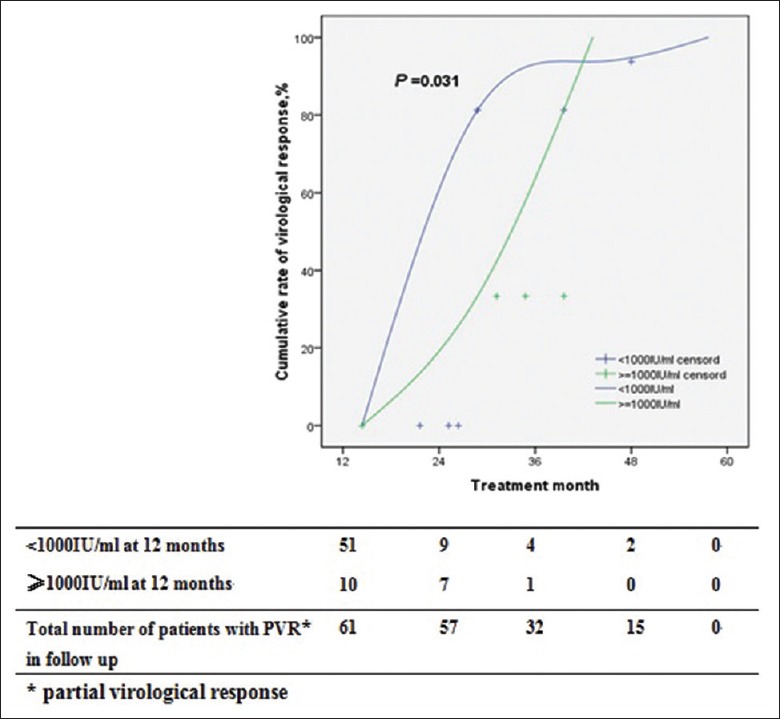

We stratified patients with PVR according to their viral load at 12 months [Figure 3]. The cumulative rate of achieving VR in patients with HBV DNA at <1000 IU/ml at 12 months was significantly higher than that in patients with HBV DNA at ≥1000 IU/ml at 12 months (P = 0.031).

Figure 3.

Cumulative rates of virological response in patients with partial virological response according to HBV DNA levels at 12 months. PVR: Partial virological response.

Hepatitis B s antigen loss

HBsAg loss did not occur in this study.

Hepatitis B e antigen clearance and hepatitis B e antigen seroconversion

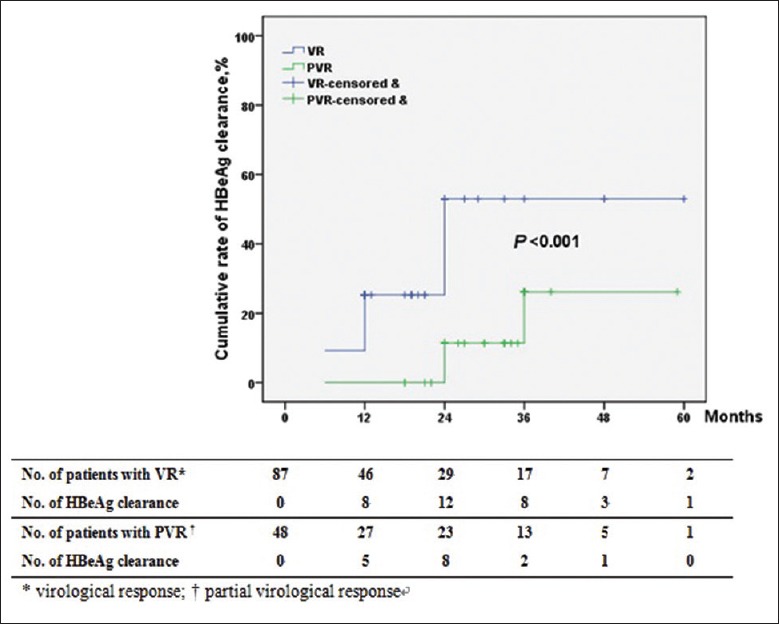

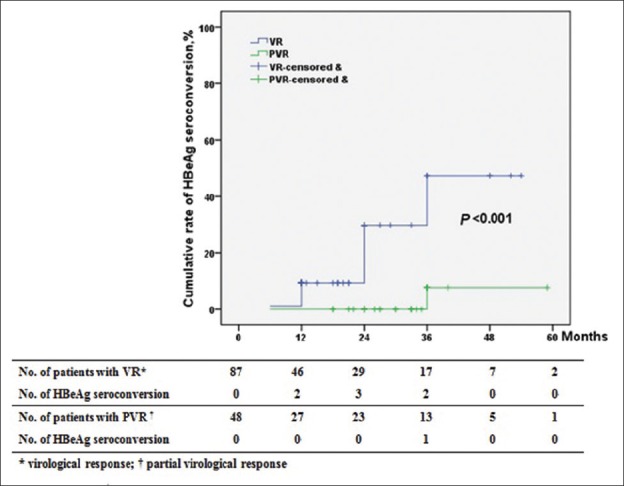

Of the 135 HBeAg-positive patients, the cumulative rates of HBeAg clearance were 2.2%, 12.6%, 23.0%, 27.4%, 28.2%, 28.2%, and 28.2% at 3, 6, 12, 24, 36, 48, and 60 months, respectively. The cumulative rates of HBeAg seroconversion at 3, 6, 12, 24, 36, 48, and 60 months were 0, 5.2%, 11.9%, 12.6%, 12.6%, 12.6%, and 12.6%, respectively. The cumulative rates of HBeAg clearance and HBeAg seroconversion in patients with VR were significantly higher than those in patients with PVR (P < 0.001) [Figures 4 and 5]. In other words, prolonged ETV therapy is more effective for HBeAg clearance and HBeAg seroconversion in patients with VR than in patients with PVR.

Figure 4.

Cumulative rates of HBeAg clearance in patients according to virological response.

Figure 5.

Cumulative rates of HBeAg seroconversion in patients according to virological response.

Among the 87 HBeAg-positive patients with VR, 32 patients achieved HBeAg clearance, and 16 patients achieved HBeAg seroconversion, but of the 48 HBeAg-positive patients with PVR, only seven patients achieved HBeAg clearance, and 1 patient achieved HBeAg seroconversion. Multivariate analysis identified PVR as the only significant determinant of HBeAg clearance (HR, 0.341; 95% CI, 0.132–0.882; P = 0.026) [Table 3].

Table 3.

Factors associated with HBeAg clearence in ETV-treated patients

| Variable | Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI) | P | HR (95% CI) | P | |

| Age | 0.986 (0.953–1.020) | 0.419 | – | – |

| Male | 2.128 (0.938–4.827) | 0.071 | – | – |

| Baseline HBV DNA (log10 IU/ml) | 0.661 (0.461–0.949) | 0.025 | 0.777 (0.530–1.139) | 0.196 |

| Baseline HBeAg (S/CO) | 0.999 (0.997–1.000) | 0.038 | 0.999 (0.998–1.000) | 0.061 |

| Baseline ALT (U/L) | 0.999 (0.997–1.001) | 0.327 | – | – |

| PVR | 0.293 (0.118–0.731) | 0.008 | 0.341 (0.132–0.882) | 0.026 |

PVR: Partial virological response; ETV: Entecavir; HBeAg: Hepatitis B e antigen; HBV: Hepatitis B virus; ALT: Alanine aminotransferase; HR: Hazard ratio; CI: Confidence interval. S/CO: Signal-to-cutoff.

Virological breakthrough

No HBeAg-negative patients experienced VB. Two HBeAg-positive patients showed VB during the treatment period (36 and 60 months). Both of patients experienced a transient VR at 12 months, but VB was finally developed during ETV treatment. Confirmed on repeat testing but genotypic resistance testing was not performed. As a rescue therapy, one patient was treated with ETV plus ADV, and the other was switched to TDF monotherapy. Both of them achieved undetectable HBV DNA levels again.

Cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma

Cirrhosis occurred in 10 (4.3%) patients with a median period of 16.5 (6–25) months after initiation of ETV treatment. There was no significant difference in the development of cirrhosis between HBeAg-positive and HBeAg-negative patients (6 [4.4%] vs. 4 [4.1%], P = 0.893) [Table 1]. Seven of these patients achieved undetectable HBV DNA levels before the occurrence of cirrhosis. Three patients were diagnosed of cirrhosis during the first 12 months of ETV therapy. Multivariate analysis identified age (HR, 1.072; 95% CI, 1.015–1.132; P = 0.013) and PVR (HR, 5.131; 95% CI, 1.344–19.587; P = 0.017) as the significant determinants of cirrhosis [Table 4].

Table 4.

Factors associated with liver cirrhosis in ETV-treated patients

| Variable | Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI) | P | HR (95% CI) | P | |

| Age | 1.069 (1.013–1.128) | 0.016 | 1.072 (1.015–1.132) | 0.013 |

| Male | 2.086 (0.568–7.669) | 0.268 | – | – |

| Baseline HBV DNA (log10 IU/ml) | 0.804 (0.462–1.401) | 0.442 | – | – |

| Baseline ALT (U/L) | 0.998 (0.993–1.004) | 0.504 | – | – |

| HBeAg positivity | 1.093 (0.300–3.982) | 0.893 | – | – |

| Baseline HBeAg (S/CO) | 0.999 (0.996–1.002) | 0.437 | – | – |

| PVR | 4.582 (1.247–16.834) | 0.022 | 5.131 (1.344–19.587) | 0.017 |

| HBeAg clearence | 2.583 (0.498–13.396) | 0.258 | – | – |

PVR: Partial virological response; ETV: Entecavir; HBeAg: Hepatitis B e antigen; HBV: Hepatitis B virus; ALT: Alanine aminotransferase; HR: Hazard ratio; CI: Confidence interval. S/CO: Signal-to-cutoff.

HCC was diagnosed in 5 (2.1%) patients with a median period of 21 (16–24) months after ETV treatment. There was no significant difference in the development of HCC between HBeAg-positive and HBeAg-negative patients (3 [2.2%] vs. 2 [2.0%], P = 0.925) [Table 1]. Four of these patients achieved undetectable HBV DNA levels before the diagnosis of HCC. No patient was diagnosed to have HCC during the first 12 months of ETV treatment.

DISCUSSION

This is a multicenter study demonstrating that long-term ETV treatment effectively suppressed HBV viral replication in treatment-naive CHB patients in real-world clinical practice. We have reported the cumulative rates of achieving VR, PNR, PVR, and HBeAg clearance/seroconversion at 3, 6, 12, 24, 48, and 60 months after ETV treatment. It is the first time to identify the cumulative rates of HBV DNA undetectable and HBeAg clearance/seroconversion at 3 and 6 months after ETV treatment.

The APASL 2015[5] and the European Association of Study of Liver Diseases (EASL) 2012[7] clinical practice guidelines on the management of chronic hepatitis B suggested that stipulate 3 and/or 6 month HBV DNA should be measured during therapy in patients with high genetic barrier to resistance who are on entecavir treatment. In this study, it is the first time to identified the cumulative rates of HBV DNA undetectable and HBeAg clearance/seroconversion at months 3 and 6 after ETV treatment.

In previous studies, some trials showed 67% of HBV DNA undetectable rate, and 21% of HBeAg seroconversion rate after 1 year of treatment in HBeAg-positive patients.[11] In HBeAg-negative patients, HBV DNA undetectable rate was 90% after 1 year of ETV treatment.[12] Some studies provided further follow-up data with 94% of undetectable HBV DNA, 23% of HBeAg seroconversion rate in HBeAg-positive patients after 5 years.[8] Obviously, the VR rates in our study were consistent with previous studies, but the rates of HBeAg seroconversion were lower. These results may reflect the differences between clinical trials that enrolled selected patients and effectiveness observations in “real-world” settings enrolling more heterogeneous patients. Because real-world studies contain a heterogeneous mixture of patients who are differentiated from those in clinical trials based on a number of criteria, they may be more reflective in the treatment population and the real efficacy and safety of the drug.

Given that early VR may predict better outcomes and a reduced risk of viral resistance, PVR is an indication for a therapy change according to current practice guidelines. However, these guidelines are based on the data from studies of drugs with a higher risk of antiviral resistance.[13,14,15] Some studies demonstrated that CHB patients with PNR after the initiation of ETV treatment displayed as lower rate of reduction of viremia, but the vast majority of patients finally become HBV DNA undetectable in the primary responders.[13,14,15] In our study, the rate of PNR was 1.3% and all PNR patients achieved VR finally, which is consistent with the results of previous studies. That means long-term ETV therapy generally leads to a VR, although the time to achieve it is delayed in PNRs. The current recommendation to change therapy in PNRs needs to be modified to reflect drug differences in antiviral potency and resistance risk.

Current guidelines recommend that CHB patients with a PVR to ETV treatment, the agent with a high genetic barrier to drug resistance, should undergo further monitoring without therapy change until 48 weeks.[5,6,7] Only at that stage, a decision for whether to change therapy should be made.[5,6,7] In a study from Korea, a total of 28 (28/202) patients experienced PVR to ETV treatment. VR was achieved in 21 of these patients during the follow-up period. The overall cumulative rates of VR in NA-naïve patients with PVR were 66.7%, 86.7%, and 93.3% at 96, 144, and 192 weeks, respectively.[16] In is study, PVR occurred in 61 (26.2%) patients, the cumulative rates of VR in patients with PVR were 68.9%, 80.3%, 82.0% at 24, 36, and 48 months, respectively. It is true that most NA-naïve patients with PVR achieved VR during long-term ETV therapy. In other words, in the patients with PVR but without ETV resistance, prolonged ETV therapy without treatment adaptation was effective for achieving VR.

Several studies reported that the rates of PVR to ETV in NA-naïve patients ranged from 11.3% to 14.6%.[17,18,19] These studies identified high HBV DNA at baseline,[17,18] high HBV DNA at 24 weeks,[19] and HBeAg positivity[17] as risk factors for PVR. In our study, we evaluated the factors associated with PVR to ETV and long-term virologic outcomes. We found that PVR was associated with a high level of serum HBV DNA levels at baseline and NA-naïve patients with PVR had favorable virological outcomes. HBV DNA below 1000 IU/ml at 12 months was associated with subsequent achievement of VR in the patients with PVR to ETV.

In contrast to the view that CHB patients with primary treatment failure are at risk of genotypic resistance,[20,21,22] there were no primary nonresponders and no partial virological responsers who achieved virological breakthrough subsequently. This observation supports the conclusion that there is no need for early treatment adjustment in slow responders.

Because of the persistence of nuclear covalently closed circular DNA and HBV DNA integrated into the host genome, HBV is not completely eradicated by treatment, even if HBsAg loss occurs. Long-term therapy is required in patients who cannot maintain virologic suppression off-treatment and for those with advanced liver disease. One barrier to the success of long-term therapy is the emergence of drug-resistant mutants. ETV is associated with a low rate of resistance in treatment-naïve patients (1.2 % of patients treated for up to 5 years),[10] However, rates of ETV resistance are higher in those who are ADV nonresponders (4 % of patients treated for a median of 20 months),[23] lamivudine resistant (51 % of patients treated for up to 5 years).[24] The patients included in our study were all treatment naïve. More studies including treatment-experienced patients are in need.

Long-term ETV therapy has been shown to improve fibrosis in patients with CHB.[8,25,26] However, there are still few CHB patients developing cirrhosis. Multivariate analysis in our study identified age and PVR as the significant determinants of cirrhosis. Idilman et al. found that the cumulative rates of HCC increased from 3.3% at 1 year to 7.3% at 4 years after antiviral therapy.[27] The present study got the similar results of HCC development. Several studies have mentioned that older age, high HBV viral load and the presence of cirrhosis were associated with the development of HCC.[28,29] The lack of such associations in the current study may be attributed to the fact that our study included too few patients and too small number of HCC cases to conduct the statistics analysis.

The limitations of this study are inherent in its retrospective study design. Selection criteria are less strict than in randomized controlled trials, and confounding factors can interfere with the interpretation of results. Because data were obtained from patients’ medical charts, the proportion of patients with missing data was large and some variables could not be included in the analysis because the sample size was small. This reduced the sensitivity of the analysis and may also have introduced some attrition bias. Laboratory tests were performed locally, which might influence our assessment of VR and HBeAg seroconversion. HBV DNA assays were performed locally with detection limits 20–500 IU/ml, and contributed to the exclusion of 338 patients based on the inclusion criteria defining the VR as HBV DNA <20 IU/ml. Despite these limitations, this study provides some insights into the determinants of treatment initiation and switch.

In summary, ETV treatment was effective for HBV DNA suppression in this study, but HBsAg loss and HBeAg clearance/seroconversion rates were lower than previously reported in clinical trials. PVR was associated with HBeAg clearance and cirrhosis.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

We sincerely appreciate the technical supported provided by Yongqian Tian and Pei Shao (Ashermed Healthcare Communications Company, Shanghai, China).

Footnotes

Edited by: Li-Min Chen

REFERENCES

- 1.Tong MJ, Pan CQ, Hann HW, Kowdley KV, Han SH, Min AD, et al. The management of chronic hepatitis B in Asian Americans. Dig Dis Sci. 2011;56:3143–62. doi: 10.1007/s10620-011-1841-5. doi: 10.1007/s10620-011-1841-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fattovich G, Bortolotti F, Donato F. Natural history of chronic hepatitis B: Special emphasis on disease progression and prognostic factors. J Hepatol. 2008;48:335–52. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2007.11.011. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2007.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chen CJ, Yang HI. Natural history of chronic hepatitis B REVEALed. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;26:628–38. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2011.06695.x. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2011.06695.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kim HY, Kim CW, Choi JY, Park CH, Lee CD, Yim HW. A Decade-old change in the screening rate for hepatocellular carcinoma among a hepatitis B Virus-infected population in Korea. Chin Med J (Engl) 2016;129:15–21. doi: 10.4103/0366-6999.172551. doi: 10.4103/0366-6999.172551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sarin SK, Kumar M, Lau GK, Abbas Z, Chan HL, Chen CJ, et al. Asian-Pacific clinical practice guidelines on the management of hepatitis B: A 2015 update. Hepatol Int. 2016;10:1–98. doi: 10.1007/s12072-015-9675-4. doi: 10.1007/s12072-015-9675-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Terrault NA, Bzowej NH, Chang KM, Hwang JP, Jonas MM, Murad MH. American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. AASLD guidelines for treatment of chronic hepatitis B. Hepatology. 2016;63:261–83. doi: 10.1002/hep.28156. doi: 10.1002/hep.28156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.European Association for the Study of the Liver. EASL clinical practice guidelines: Management of chronic hepatitis B virus infection. J Hepatol. 2012;57:167–85. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2012.02.010. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2012.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chang TT, Lai CL, Kew Yoon S, Lee SS, Coelho HS, Carrilho FJ, et al. Entecavir treatment for up to 5 years in patients with hepatitis B e antigen-positive chronic hepatitis B. Hepatology. 2010;51:422–30. doi: 10.1002/hep.23327. doi: 10.1002/hep.23327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhang XX, Li MR, Xi HL, Cao Y, Zhang RW, Zhang Y, et al. Dynamic characteristics of serum hepatitis B surface antigen in Chinese chronic hepatitis b patients receiving 7 years of entecavir therapy. Chin Med J (Engl) 2016;129:929–35. doi: 10.4103/0366-6999.179802. doi: 10.4103/0366-6999.179802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tenney DJ, Rose RE, Baldick CJ, Pokornowski KA, Eggers BJ, Fang J, et al. Long-term monitoring shows hepatitis B virus resistance to entecavir in nucleoside-naïve patients is rare through 5 years of therapy. Hepatology. 2009;49:1503–14. doi: 10.1002/hep.22841. doi: 10.1002/hep.22841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cai S, Yu T, Jiang Y, Zhang Y, Lv F, Peng J. Comparison of entecavir monotherapy and de novo lamivudine and adefovir combination therapy in HBeAg-positive chronic hepatitis B with high viral load: 48-week result. Clin Exp Med. 2016;16:429–36. doi: 10.1007/s10238-015-0373-2. doi: 10.1007/s10238-015-0373-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang LC, Chen EQ, Cao J, Liu L, Zheng L, Li DJ, et al. De novo combination of lamivudine and adefovir versus entecavir monotherapy for the treatment of naïve HBeAg-negative chronic hepatitis B patients. Hepatol Int. 2011;5:671–6. doi: 10.1007/s12072-010-9243-x. doi: 10.1007/s12072-010-9243-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lok AS, McMahon BJ. Chronic hepatitis B: Update 2009. Hepatology. 2009;50:661–2. doi: 10.1002/hep.23190. doi: 10.1002/hep.23190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zeuzem S, Gane E, Liaw YF, Lim SG, DiBisceglie A, Buti M, et al. Baseline characteristics and early on-treatment response predict the outcomes of 2 years of telbivudine treatment of chronic hepatitis B. J Hepatol. 2009;51:11–20. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2008.12.019. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2008.12.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nguyen MH, Keeffe EB. Chronic hepatitis B: Early viral suppression and long-term outcomes of therapy with oral nucleos(t)ides. J Viral Hepat. 2009;16:149–55. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2893.2009.01078.x. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2893.2009.01078.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jo YJ, Kim KA, Lee JS, Kim NH, Bae WK, Song TJ, et al. Long-term virological outcome in chronic hepatitis B patients with a partial virological response to entecavir. Korean J Intern Med. 2015;30:170–6. doi: 10.3904/kjim.2015.30.2.170. doi: 10.3904/kjim.2015.30.2.170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zoutendijk R, Reijnders JG, Brown A, Zoulim F, Mutimer D, Deterding K, et al. Entecavir treatment for chronic hepatitis B: Adaptation is not needed for the majority of naïve patients with a partial virological response. Hepatology. 2011;54:443–51. doi: 10.1002/hep.24406. doi: 10.1002/hep.24406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ko SY, Choe WH, Kwon SY, Kim JH, Seo JW, Kim KH, et al. Long-term impact of entecavir monotherapy in chronic hepatitis B patients with a partial virologic response to entecavir therapy. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2012;47:1362–7. doi: 10.3109/00365521.2012.719927. doi: 10.3109/00365521.2012.719927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bang SJ, Kim BG, Shin JW, Ju HU, Park BR, Kim MH, et al. Clinical course of patients with insufficient viral suppression during entecavir therapy in genotype C chronic hepatitis B. Dig Liver Dis. 2013;45:600–5. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2012.12.013. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2012.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chan HL, Wong VW, Tse CH, Chim AM, Chan HY, Wong GL, et al. Early virological suppression is associated with good maintained response to adefovir dipivoxil in lamivudine resistant chronic hepatitis B. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2007;25:891–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2007.03272.x. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2007.03272.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yuen MF, Sablon E, Hui CK, Yuan HJ, Decraemer H, Lai CL. Factors associated with hepatitis B virus DNA breakthrough in patients receiving prolonged lamivudine therapy. Hepatology. 2001;34:785–91. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2001.27563. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2001.27563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chan HL, Heathcote EJ, Marcellin P, Lai CL, Cho M, Moon YM, et al. Treatment of hepatitis B e antigen positive chronic hepatitis with telbivudine or adefovir: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2007;147:745–54. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-147-11-200712040-00183. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-147-11-200712040-00183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Marcellin P, Chang TT, Lim SG, Tong MJ, Sievert W, Shiffman ML, et al. Adefovir dipivoxil for the treatment of hepatitis B e antigen-positive chronic hepatitis B. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:808–16. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa020681. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa020681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lok AS, Lai CL, Leung N, Yao GB, Cui ZY, Schiff ER, et al. Long-term safety of lamivudine treatment in patients with chronic hepatitis B. Gastroenterology. 2003;125:1714–22. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2003.09.033. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2003.09.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gish RG, Lok AS, Chang TT, de Man RA, Gadano A, Sollano J, et al. Entecavir therapy for up to 96 weeks in patients with HBeAg-positive chronic hepatitis B. Gastroenterology. 2007;133:1437–44. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.08.025. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.08.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chang TT, Liaw YF, Wu SS, Schiff E, Han KH, Lai CL, et al. Long-term entecavir therapy results in the reversal of fibrosis/cirrhosis and continued histological improvement in patients with chronic hepatitis B. Hepatology. 2010;52:886–93. doi: 10.1002/hep.23785. doi: 10.1002/hep.23785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Idilman R, Gunsar F, Koruk M, Keskin O, Meral CE, Gulsen M, et al. Long-term entecavir or tenofovir disoproxil fumarate therapy in treatment-naïve chronic hepatitis B patients in the real-world setting. J Viral Hepat. 2015;22:504–10. doi: 10.1111/jvh.12358. doi: 10.1111/jvh.12358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Singal AK, Salameh H, Kuo YF, Fontana RJ. Meta-analysis: The impact of oral anti-viral agents on the incidence of hepatocellular carcinoma in chronic hepatitis B. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2013;38:98–106. doi: 10.1111/apt.12344. doi: 10.1111/apt.12344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chen CJ, Yang HI, Su J, Jen CL, You SL, Lu SN, et al. Risk of hepatocellular carcinoma across a biological gradient of serum hepatitis B virus DNA level. JAMA. 2006;295:65–73. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.1.65. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.1.65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]