Abstract

The aims of the current study were to prepare chitosan nanoparticles (CNPs) and to evaluate its protective role alone or in combination with quercetin (Q) against AFB1-induce cytotoxicity in rats. Male Sprague-Dawley rats were divided into 12 groups and treated orally for 4 weeks as follow: the control group, the group treated with AFB1 (80 μg/kg b.w.) in corn oil, the groups treated with low (140 mg/kg b.w.) or high (280 mg/kg b.w.) dose of CNPs, the group treated with Q (50 mg/kg b.w.), the groups treated with Q plus the low or the high dose of CNPs and the groups treated with AFB1 plus Q and/or CNPs at the two tested doses. The results also revealed that administration of AFB1 resulted in a significant increase in serum cytokines, Procollagen III, Nitric Oxide, lipid peroxidation and DNA fragmentation accompanied with a significant decrease in GPx I and Cu–Zn SOD-mRNA gene expression. Q and/or CNPs at the two tested doses overcome these effects especially in the group treated with the high dose of CNPs plus Q. It could be concluded that CNPs is a promise candidate as drug delivery enhances the protective effect of Q against the cytogenetic effects of AFB1 in high endemic areas.

Keywords: Aflatoxin B1, Chitosan nanoparticles, Quercetin, Genotoxicity, Liver, Gene expression

1. Introduction

Aflatoxin B1 (AFB1) is mainly synthesized by Aspergillus flavus and Aspergillus parasiticus, and is commonly found as a contaminant in cereals and oilseeds. It is one of the most relevant mycotoxins worldwide due to its widespread occurrence, high toxicity and economic implications [1]. The exposure to AFB1 resulted in growth stunting, immunosuppression, mutagenicity, genotoxicity, increasing hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) incidence in animals and humans [2], [3], [4]. The genotoxic and carcinogenic effects of AFB1 are intimately linked with its biotransformation through the cytochrome P450 to the highly reactive AFB1-exo-8,9-epoxide, which can form adducts with the DNA [5] and produce reactive oxygen species (ROS) [6], [7]. Moreover, AFB1 carcinogenicity has been associated with altered expression of many p53-target genes and induction of mutations, principally the p53 codon 249 hotspot mutation [8].

Hepatic diseases represent a serious health problem all over the world and the modern medicine as well as the traditional herbal formulations offers few effective treatments [9]. Numerous medicinal plant formulations are used to treat liver disorders in traditional therapy. Most of these treatments act as radical scavengers, whereas others are enzyme inhibitors or mitogens [10]. Quercetin (Q) is a major flavonoid widely found in natural plants and has become an essential part of the human diet. It has been attested that the average daily intake of Q in the diet of the Netherlands is 23 mg [11]. Recently, Q has drawn attention for its remarkable scope of health benefits, which make it a leading compound for developing new and effective functional foods or medicines [11], [12]. It is well documented that Q has broad bioactivity, such as anti-proliferative and anticancer properties [13], [14], anti-fibrotic [15], [16], anti-coagulative [17], anti-bacterial [18], anti-atherogenic [19], [20], anti-hypertensive [21], [22] and anti-inflammatory capacities [23], [24], [25], [26]. Several studies have reported that Q possessing an excellent efficacy of scavenging free radicals [27], which is stronger than the traditional antioxidants Vitamin C and Vitamin E [28]. However, the solubility of Q is poor due to its chemical structure which is known to have low bioavailability, and only a small percentage of ingested Q is absorbed into circulation [12]. Therefore, various attempts have been made to improve the bioavailability of Q via chemical modification [29].

Chitosan (CS) is an amino polysaccharide derived from deacetylation of chitin of arthropods and insects exoskeleton and considered a dietary fiber due to indigestibility by digestive enzymes [30]. CS has many functions in the fields of biomedicinal and pharmaceutical products, food preservation and microbial mitigation [31]. These biological activities include immunopotentiating, antitumor, antihypertensive, and antimicrobial actions [32], [33], antioxidant properties and free radical scavenging activity [34], [35], [36]. CS was reported to affect the mitogenic response as well as the chemotactic activities of animal cells [37] and is believed to treat obesity in humans [38] and reduces both body weight and cholesterol in animals and humans [39], [40]. However, because of its high molecular weight and water-insolubility, the applications of CS are severely limited. As a solution, nanoparticle formulation provides a plausible pharmaceutical basis for enhancing oral bioavailability and therapeutic efficacy of CS and other drugs that are poorly soluble [41]. Chitosan nanoparticles (CNPs) exhibit more superior activities than CS and have been reported to have heightened immune-enhancing effect, anticancer activity and antimicrobial activity than those of CS. In addition, nanoparticles possess a stronger curvature of the surface, compared to large particles [42]. The increased saturation solubility, in turn, favors an increase in concentration gradient between intestinal epithelial cells and the mesenteric circulation beneath. The aims of the present study were to prepare and characterize CNPs and to evaluate the possible hepatoprotective activity of CNPs and Q singly or in combination against AFB1-induced oxidative stress and cytotoxicity in rat liver.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Chemical and kits

Chitosan (high molecular weight, Mw 165–175 kDa) was purchased from Sigma–Aldrich (Paris, France). Aflatoxin B1 (AFB1) standards, quercetin extract, Sodium tripolyphosphate (TPP) AND RevertAid™ H Minus First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit were purchased from Sigma Chemical Co. (St. Louis, MO, USA). Interleukin-1α (IL-1 α), Procollagen III and Tumor Necrosis Factor-alpha (TNF-α) kits were purchased from Orgenium (Helsinki, Finland). Glutathione peroxidase (GPx) and Superoxide dismutase (SOD), lipid peroxidation (MDA), nitric oxide (NO) and carcinoembrionic antigen (CEA) kits were purchased from Biodiagnostic Co. (Giza, Egypt). TRIZOL reagent was purchased from Invitrogen™ (Carlsbad, CA, USA). All other chemicals used throughout the experiments were of the highest analytical grade available.

2.2. Preparation and characterization of chitosan nanoparticles (CNPs)

Twenty mg CS was dissolved in 40 ml of 2.0% (v/v) acetic acid. A 20 ml of 0.75 mg/ml sodium tripolyphosphate was dropped slowly with stirring. Supernatant was discarded and CNPs were collected and air dried for further use and analysis [43]. The size of CNPs was determined using Nanotrac analyzer 6Hx4Wx15D, Model – Nanotrac 150 (Betatek Inc., Toronto, ON, Canada) with a measuring range of 0.8–6500 nm (10–9 m). CNPs were cut into pieces of various sizes and wiped with a thin gold–palladium layer by a sputter coater unit (UG-microtech, UCK field, UK). FTIR spectra of CS and CNPs were determined using an infrared spectrometer (FTIR) (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., Nico-let iS10, USA). Powdered CNPs were obtained by freeze-drying and the samples were prepared using KBr to form pellets. Using UV–vis spectrophotometric method, UV–vis spectra of electrolyte solution of CS and CNPs were obtained using a perkin-Elmer UV–Vis Lambda 35 spectrophotometer scanning 200–800 nm. All measurements were carried out at least in triplicate.

2.3. Animals and experimental design

Three-month old male Sprague-Dawley rats (100–150 g each) were purchased from Animal House Colony, National Research Center, Dokki, Giza, Egypt. Animals were maintained on standard lab diet (protein: 160.4; fat: 36.3; fiber: 41 g/kg, namely 12.1 MJ of metabolized energy) purchased from Meladco Feed Co. (Aubor City, Cairo, Egypt) and housed in filter-top polycarbonate cages in a room free from any source of chemical contamination, artificially illuminated (12 h dark/light cycle) and thermally controlled (25 ± 1 °C) at the Animal House Lab., National Research Center, Dokki, Cairo, Egypt. All animals were received humane care in compliance with the guidelines of the Animal Care and Use Committee of the National Research Center, Dokki, Giza, Egypt and the National Academy of Sciences and published by the National Institutes of Health (NIH publication 86-23 revised 1985).

Animals were divided into twelve groups (10 rats/group) and were maintained on their respective diet for 4 weeks as follow: group 1, normal control animals; Group 2, animals treated orally with AFB1 (80 μg/kg b.w.) suspended in corn oil; Groups 3 and 4, animals treated daily with low (140 mg/kg b.w.) and high (280 mg/kg b.w.) dose of CNPs (CNPs-LD, CNPs-HD); Group 5, animals treated daily with Q (50 mg/kg b.w.); Groups 6 and 7, animals treated orally with Q plus CNPs-LD or CNPs-HD respectively; Groups 8 and 9, animals treated orally with AFB1 plus CNPs-LD and CNPs-HD respectively; Group 10, animals treated orally with AFB1 plus Q; Groups 11 and 12, animals treated orally AFB1 plus Q and CNPs-LD or CNPs-HD respectively. The animals were observed daily for signs of toxicity during the experimental period. At the end of the treatment period (i.e. day 28), all animals were fasted for 12 h, then blood samples were collected from the retro-orbital venous plexus under diethyl ether anesthesia. Sera were separated using cooling centrifugation and stored at −20 °C until analysis. The sera were used for the determination of IL-α, Procollagen III, NO, TNF-α and CEA according to the kits instructions.

After the collections of blood samples, animals were sacrificed and samples of the liver of each animal were dissected, weighed and homogenized in phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) to give 20%, w/v, homogenate according to Lin et al. [44]. This homogenate was centrifuged at 1700 rpm at 4 °C for 10 min; the supernatant was stored at −70 °C until analysis. This supernatant (20%) was used for the determination of hepatic lipid peroxidation (MDA) and it was further diluted with phosphate buffer solution to give 2 and 0.5% dilutions for the determination of hepatic GPx (2%) and SOD (0.5%) activities according to the kits instructions. Other samples of liver each animal were dissected for molecular analyses.

2.4. Molecular analyses

2.4.1. Total RNA extraction

Frozen liver tissue samples (50–100 μg) from each animal within different treatment groups were thawed and homogenized in TRIZOL reagent. The solution of extracted RNA was recovered in 100 μl molecular biology grade water. The total RNA samples were pretreated using DNA-free™ DNase to remove any possible genomic DNA contamination according to manufacturer's protocol. The quality of the RNA was determined using spectrophotometer at 260 nm by UV visualization of an ethidium bromide-stained agarose-formalin gel.

2.4.2. Reverse transcription

Single strand cDNA was synthesized for PCR and semi-nested PCR purposes using total RNA isolated from different tissues and oligo(dT)18 as primer for reverse transcriptase. The reaction mixture of 20 μl used in the 1st step of cDNA synthesis included 4 μl of total RNA (2 μg), 0.5 μl oligo(dT)18 (10 μM), and 5 μl of DEPC-treated water. The reaction mixture was incubated at 70 °C for 5 min. A 4 μl of 5X M-MuLV-Reverse Transcriptase buffers, 2 μl of 10 mM dNTP mix, 0.5 μl of dH2O and 0.5 μl (20 units) of ribonuclease inhibitor was added to the above reaction mixture. The above mixtures were further incubated at 37 °C for 5 min. 2 μl (40 units) M-MuLV-Reverse Transcriptase was then added and cDNA was synthesized for 60 min at 42 °C. The reaction was stopped by heating the reaction mixture at 70 °C for 10 min. The cDNA thus synthesized was stored at −20 °C.

2.4.3. Polymerase chain reaction (PCR)

The first-strand cDNA from different rat samples was used as the template for amplification by the PCR with the pairs of specific primers presented in Table 1 (from 5′ to 3′) according to Limaye et al. [45]. β-Actin, a house-keeping gene was used for normalizing mRNA levels of the target genes. The PCR cycling parameters were one cycle of 94 °C for 5 min, 35 cycles of 94 °C for 30 s, 60 °C for 30 s, 70 °C for 40 s, and 72 °C for 5 min for Cu–Zn SOD using hydrogen peroxidae and for GPx I gene using horseradish peroxidase substrate according to the instructions supplied by the producer company. The PCR product was run on a 1.5% agarose gel in Tris-borate-EDTA buffer and visualized over a UV Trans-illuminator. The ethidium bromide-stained gel bands were scanned and the signal intensities were quantified by the computerized Gel-Pro (version 3.1 for window 3). The ratio between the levels of the target gene amplification product and the β-actin (internal control) was calculated to normalize for initial variation in the sample concentration as a control for reaction efficiency [46]. All PCRs were independently replicated three times.

Table 1.

Details giving primer sequences and expected product sizes for the genes amplified.

| cDNA | Genbank accession no. | Forward primer | Reverse primer | RT-PCR product size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| β-Actin | V01217 | 5′-CTGCTTGCTGATCCACA | 5′-CTGACCGAGCGTGGCTAC | 505 bp |

| Cu–Zn SOD | X05634 | 5′-GCAGAAGGCAAGCGGTGAAC | 5′-TAGCAGGACAGCAGATGAGT | 387 bp |

| GPx I | M21210 | 5′-CTCTCCGCGGTGGCACAGT | 5′-CCACCACCGGGTCGGACATAC | 290 bp |

Cu–Zn SOD – copper zinc superoxide dismutase; GPx I – glutathione peroxidase.

2.5. Quantification of DNA fragmentation

DNA fragmentation in liver tissue was carried out according to Wu et al. [47] with some modification. Briefly, about 50 mg of liver tissue were homogenized in lysis buffer pH 8.0 (10 mM Tris base, 1 mM EDTA and 0.2% triton X-100) and incubated on ice for 20 min. The cell lysate were centrifuged at 12,000 rpm for 30 min at 4 °C. The supernatant containing small DNA fragments was separated. The supernatant and pellet were re-suspended in 1 N and 0.5 N of perchloric acid respectively. Then samples were heated at 90 °C for 20 min and centrifuged at 11,000 rpm for 10 min to remove proteins. Supernatant fractions were reacted with diphenylamine (DPA) for 16–20 hr at room temperature and the developing blue color was measured at 600 nm using a UV-double beam spectrophotometer (Shimadzu 160 A; Shimadzu Corporation, Kyoto, Japan). DNA fragmentation in samples was calculated as follow: [(fragmented DNA in supernatant)/fragmented DNA in supernatant + intact DNA in pellet) × 100]. The data were expressed as percentage of total DNA appearing in the supernatant fraction.

2.6. Statistical analysis

The experimental results were expressed as the mean ± SEM with ten rats in each group. The intergroup variation between various groups were analyzed statistically using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Duncan's multiple range test [48] using statistics software package SPSS for Windows, V. 13.0 (Chicago, USA). P values ≤0.05 were considered as statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. Characterization of CNPs

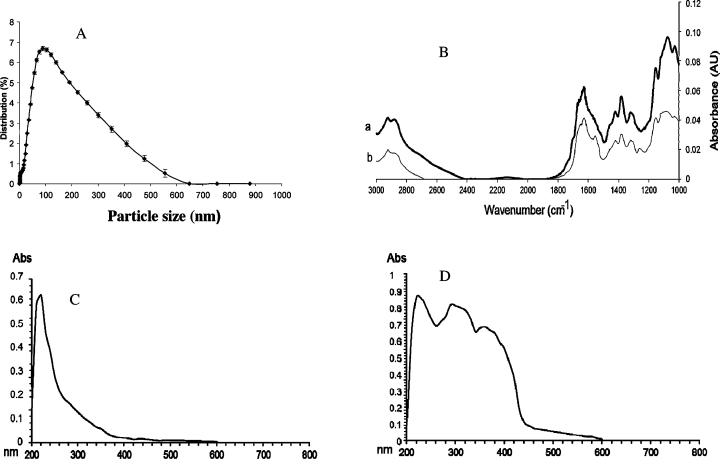

The size measurements of CNPs revealed that the average particles size was around 100 nm and size distribution was in the range of 100–600 nm (Fig. 1A). The FT-IR spectra of the CS and CNPs showed a new peak for CNPs appear at 1256 cm−1 indicating P O stretching and the intensity of NH2 band appear at 1628 cm−1, which can be observed clearly in CS and decreased dramatically since a new sorption band at 1550 cm−1 was appeared (Fig. 1B). The UV–vis spectra of CS and CNPs are shown in Fig. 1C and D and revealed significant changes in the UV/vis spectra of CNPs were observed compared to CS. Moreover, a large increase of the absorbance in the range of 250–350 and 350–450 nm was observed in the spectra of CNPs.

Fig. 1.

Characterization of CNPs showing (A) Percentage of size distribution of CNPs, (B) FT-IR spectra of (a) chitosan and (b) chitosan nano particles (CNPs), (C) UV–vis spectrum of chitosan, (D) UV–vis spectrum of CNPs (B).

3.2. Biochemical and molecular analyses

The results of the current study revealed that treatment with AFB1 resulted in a significant increase in CEA, TNF-α, IL-1α, Procollagen III and NO (Table 2). Treatment with CNPs-LD or CNPs-HD showed a significant decrease in CEA and NO but did not significantly affect TNF-α, IL-1α and Procollagen III. Treatment with Q alone resulted in a significant decrease in CEA however the other parameters were in the normal range of the control. Animals treated with Q plus CNPs-LD or CNPs-HD showed insignificant changes in TNF-α, IL-1α, Procollagen III and NO although it decreased significantly CEA. This decrease was more pronounced in the group treated with Q plus CNPs-HD. Treatment with AFB1 plus Q or CNPs at the two tested doses resulted in a significant improvement in all the tested parameters toward the control values and CNPs-HD succeeded to normalize CEA and TNF-α. On the other hand, animals treated with AFB1 plus Q and CNPs-LD showed a significant decrease in CEA level TNF-α, IL-1α, Procollagen III and NO compared to AFB1 alone-treated group and this treatment succeeded to normalize CEA. However, the group treated with AFB1 plus Q and CNPs-HD was comparable to the control group in all the parameters tested (Table 2).

Table 2.

Effect of oral administration of AFB1 alone or in combination with Q and/or CNPs on serum cytokines, procollagen III and nitric oxide.

| Parameter groups | CEA (ng/ml) | TNF-α (ng/l) | IL-1α (ng/ml) | Procollagen III (μg/l) | NO (μmol/l) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 2.75 ± 0.34a | 57.3 ± 2.95 a | 0.75 ± 0.03a | 2.6 ± 0.12a | 34.74 ± 1.93a |

| AFB1 | 9.54 ± 1.51b | 96.42 ± 2.33b | 4.24 ± 0.93b | 8.96 ± 0.86b | 85.83 ± 2.44b |

| CNPs-LD | 2.55 ± 0.62a | 55.23 ± 2.63a | 0.74 ± 0.02a | 2.55 ± 0.21a | 33.86 ± 2.45a |

| CNPs-HD | 2.66 ± 0.52a | 56.72 ± 2.47a | 0.77 ± 0.04a | 2.59 ± 0.23a | 34.62 ± 2.09a |

| Q | 2.71 ± 0.33a | 57.22 ± 2.62a | 0.76 ± 0.04a | 2.89 ± 0.31a | 35.64 ± 1.88a |

| CNPs-LD + Q | 2.77 ± 0.37a | 56.92 ± 1.94a | 0.77 ± 0.05a | 2.49 ± 0.47a | 35.43 ± 2.53a |

| CNPs-HD + Q | 2.79 ± 0.64a | 58.1 ± 3.42a | 0.77 ± 0.07a | 2.58 ± 0.41a | 35.82 ± 2.94a |

| CNPs-LD + AFB1 | 4.93 ± 0.86c | 67.53 ± 3.63c | 2.99 ± 0.75c | 5.74 ± 1.22d | 57.83 ± 2.44c |

| CNPs-HD + AFB1 | 4.22 ± 0.77c | 62.75 ± 2.96d | 2.53 ± 0.84c | 4.96 ± 1.31d | 55.83 ± 2.48c |

| Q + AFB1 | 4.76 ± 1.22c | 64.83 ± 2.67e | 2.67 ± 0.45c | 4.99 ± 1.08d | 59.84 ± 2.45c |

| CNPs-LD + Q + AFB1 | 3.95 ± 0.93d | 60.42 ± 1.69d | 1.87 ± 0.54e | 3.83 ± 0.89e | 43.82 ± 2.94d |

| CNPs-HD + Q + AFB1 | 2.83 ± 0.92a | 58.52 ± 2.66a | 1.22 ± 0.23e | 2.83 ± 0.77a | 38.32 ± 2.76e |

Within each column, means superscript with different letters are significantly different (P ≤ 0.05).

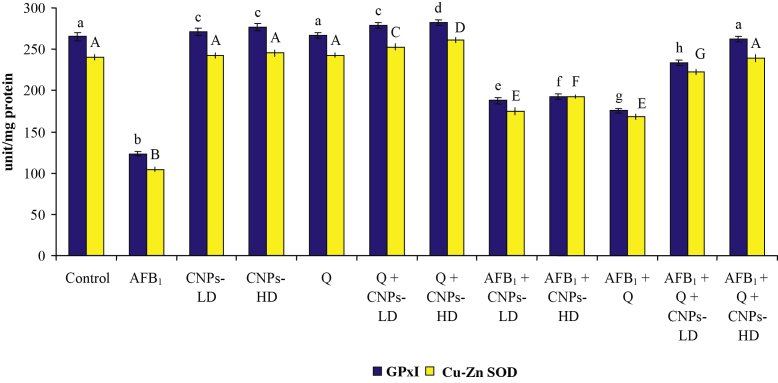

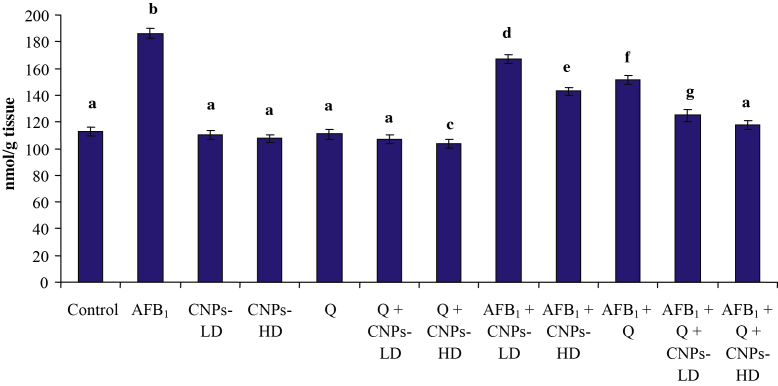

The results of the current study revealed that treatment with AFB1 resulted in a significant decrease in hepatic GPx and SOD (Fig. 2) accompanied with a significant increase in MDA (Fig. 3). Treatment with Q, CNPs-LD or CNPs-HD resulted in a significant increase in GPx and SOD accompanied with a significant decrease in MDA level only in the groups treated with CNPs-HD or Q. The combined treatment with Q and CNPs-LD or CNPs-HD resulted in a significant increase in the antioxidant enzymes accompanied with a significant decrease in MDA which was more pronounced in the group received Q plus CNPs-HD. The combined treatment with AFB1 plus Q and/or CNPs at the two tested doses succeeded to induce a significant improvement in the antioxidant enzymes and lipid peroxidation toward the control levels. Moreover, in AFB1-treated groups, Q plus CNPs-LD succeeded to normalize MDA and Q plus CNPs-HD could increase GPx and SOD above the normal level of the control group.

Fig. 2.

Effect of AFB1 administration alone or in combination with Q and/or CNPs on antioxidant enzyme activity in the liver. Data were expressed as mean ± SEM. Within each parameter, column superscripts with different letters are significantly different (P ≤ 0.05)

Fig. 3.

Effect of AFB1 administration alone or in combination with Q and/or CNPs on hepatic MDA content. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM. Within each column, means superscript with different letters are significantly different (P ≤ 0.05)

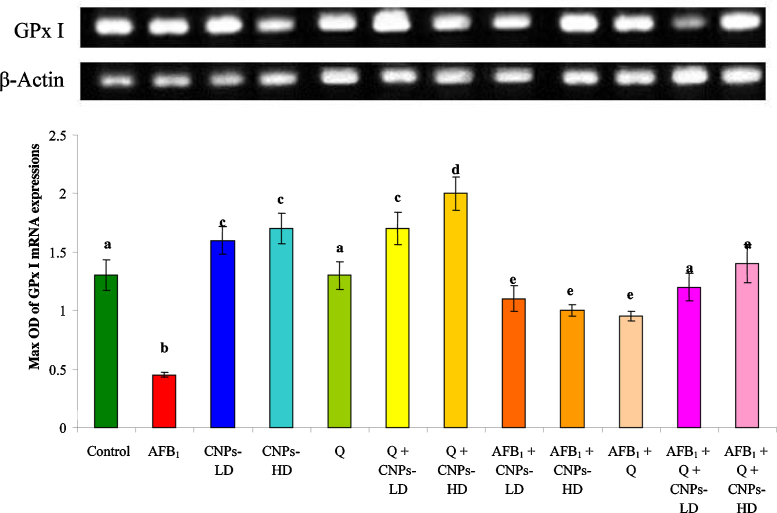

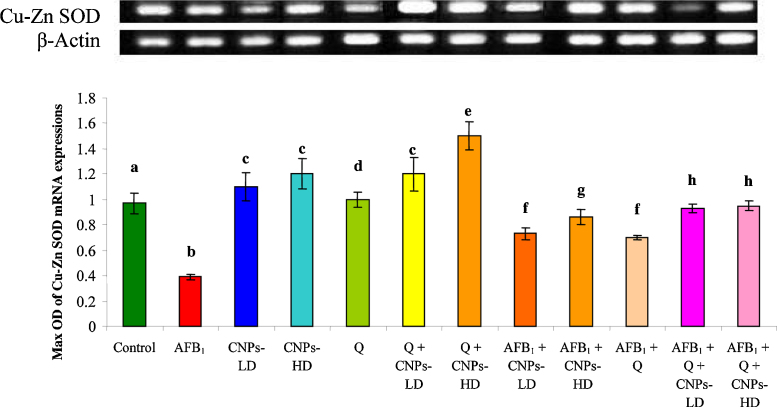

The cytogenetic results revealed that the liver genes were seriously affected with AFB1 treatment while upon treatment with CNPs whether in low or high dose, a significant improvement was achieved. The ratio of optical density indicated that the expressions of GPx mRNA (Fig. 4) and Cu–Zn SOD mRNA (Fig. 5) were significantly decreased in AFB1-treated animals compared to the control group. Treatment with CNPs-LD or CNPs-HD resulted in a significant increase in GPx mRNA and Cu–Zn SOD mRNA expression however; animals treated with Q alone were comparable to the control group. The combined treatment with Q and/or CNPs resulted in a significant increase in GPx mRNA and Cu–Zn SOD mRNA expression which was more pronounced in the group received Q plus CNPs-HD. Administration of AFB1 plus Q alone or in combination with CNPs-LD or CNPs-HD resulted in a significant improvement in GPx mRNA and Cu–Zn SOD mRNA expression toward the control level (Fig. 4, Fig. 5 respectively). This improvement was pronounced in the group treated with Q plus CNPs-LD and more pronounced in the group received Q plus CNPs-HD.

Fig. 4.

The ratio between GPx I/β-actin mRNA in rat treated with AFB1 alone or in combination with Q and/or CNPs. Values are expressed as mean ± SEM for each group. Column superscripts with different letter are significantly different (P ≤ 0.05).

Fig. 5.

The ratio between Cu–Zn SOD/β-actin mRNA in rat treated with AFB1 alone or in combination with Q and/or CNPs. Values are expressed as mean ± SEM for each group. Column superscripts with different letter are significantly different (P ≤ 0.05).

3.3. DNA fragmentation assay

The effect of different treatments on DNA damage revealed that treatment with AFB1 alone caused a significant increase in the percentage of liver genomic DNA fragmentation (Table 3) which reached 41.35% compared with the control group (6.09%). However, there was no significant change in liver genomic DNA fragmentation in the groups treated with Q and/or CNPs at the two tested doses. The administration of CNPs-LD or CNPs-HD plus AFB1 succeeded in blunting liver genomic DNA fragmentation which decreased to 24.8, 14.8% in the low and high doses respectively. However, administration of Q plus AFB1 succeeded to diminish the liver genomic DNA fragmentation which reached 27.4%. On the other hand, treatment with CNPs-LD or CNPs-HD plus Q showed a further decrease in the percentage of DNA fragmentation to reach 20.2 and 11.6%, respectively.

Table 3.

Effects of AFB1 administration alone or plus Q and/or CNPs on the percentage of DNA fragmentation in liver of rats.

| Groups | DNA fragmentation (%) | % of changes |

|---|---|---|

| Control | 6.09a | 0 |

| AFB1 | 41.35b | +35.26 |

| CNPs-LD | 5.7a | −0.39 |

| CNPs-HD | 5.4a | −0.69 |

| Q | 6.0a | −0.09 |

| CNPs-LD + Q | 5.2a | −0.89 |

| CNPs-HD + Q | 5.0a | −1.09 |

| CNPs-LD + AFB1 | 24.8c | +18.71 |

| CNPs-HD + AFB1 | 14.8d | +8.71 |

| Q + AFB1 | 27.4e | +21.31 |

| CNPs-LD + Q + AFB1 | 20.2f | +14.11 |

| CNPs-HD + Q + AFB1 | 11.6g | +5.51 |

Percentages values superscript with different letters are significantly different (P ≤ 0.05).

4. Discussion

The results of FT-IR reported in the current study showed that anionic phosphate groups of sodium polyphosphate were interacted with the cationic amino groups of CS similar to that described in previous reports [49], [50]. This interaction enhanced both the inter and intramolecular interaction of CNPs. Moreover, the results of UV–vis spectra confirmed the formation of a complex between sodium tripolyphosphate and CS. According to Fahima et al. [51], the range 250–350 nm is corresponding to the electronic transition involving the lone pair of electrons on the sodium tripolyphosphate oxygen atom and/or phosphate group. Moreover, the appearance of a broad band around 350–450 nm can be explained by the formation of the complex between the oxygen and/or phosphate groups and ammonium groups of CS. These findings give a strong evidence of the possibility of the interaction between anionic phosphate groups of sodium polyphosphate and the cationic amino groups of CS.

The in vivo results of the current study revealed that treatment with AFB1 resulted in a significant increase in CEA, TNF-α, IL-1 α, Procollagen and NO in serum. Therefore, the current study affirmed that AFB1 can induce hepatotoxicity in rats via the elevation of CEA level in serum as was suggested earlier [52], [53], [54]. It is well documented that TNF-α, IL-1α and NO are produced by macrophages and they play a vital role in tumor conditions [54], [55], [56] and TNF-α is an essential factor in tumor promotion [57]. Moreover, TNF-α is a key factor that regulates the production of other cytokines involved in chronic inflammation and tumor development, through the NF-kB pathway [58]. The role of NO in cell death is complex and the increased level of NO reported herein suggested that AFB1 preferentially affect macrophage functions [53], [59], [60], [61]. Moreover, the generation of NO by the inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) plays a key role in the cytokine-mediated cell destruction [62]. On the other hand, the increased level of Procollagen III reported in the current study in AFB1-treated rats indicated the impact of this mycotoxin on liver damage as suggested by Leonardi et al. [63] who reported that procollagen III is significantly high in patients with chronic HCV with either normal or high transaminase activity. Generally, ingestion of AFB1 significantly increased TNF-α, NO and IL-1α through its effects on macrophage functions [64] and confirmed the results of Barton et al. [65] who stated that TNF-α plays a causal role in the development of liver injury.

The decrease in GPx and SOD and the increase in MDA level in the liver of AFB1-treated rats might indirectly lead to an increase in oxidative DNA damage [53], [66], [67]. Previous studies on the mechanisms of AFB1-induced liver injury have demonstrated that glutathione and SOD play an important role in the detoxification of the reactive and toxic metabolites of this mycotoxin, and that the liver necrosis begins when the glutathione stores are almost exhausted [6], [54], [68], [69], [70], [71]. Moreover, AFB1-epoxide, the toxic metabolite of AFB1, is converted into AFB1-GSH catalyzed by the cellular glutathione-S-transferase and the level of this enzyme is critical to modulate AFB1 metabolism [72]. The decrease in GPx and SOD was further confirmed by the decrease in GPx I mRNA and Cu–Zn SOD mRNA expression in AFB1-treated animals compared to the control group. This decrease in GPx, and Cu–Zn SOD mRNA expression in the liver tissue was accordance with the previous reports [73], [74], [75], [76] and could be either due to the oxidation of transcription factors or due to the decrease in the half lives of mRNAs [77]. Consequently, under this pathological condition, the active process of cellular self-destruction, DNA fragmentation and apoptosis, might occur [69], [78].

Lipid peroxidation (LP) is one of the main manifestations of oxidative damage and it plays an important role in the toxicity and carcinogenicity [71], [79]. According to Choi et al. [80], AFB1-mediated toxicity was found to be related to its pro-oxidant potential. This is because the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) including superoxide anion (O2−), hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), and hydroxyl radical (−OH) during the metabolic process of AFB1 by liver enzymes [81]. The significant increase observed in hepatic MDA levels in the group received AFB1 alone may be attributed to the generation of a high level of free radicals, which could not be tolerated by the cellular antioxidant defense system. LP can be classified as free radical-mediated and non-free radical-mediated LP [82]. Free radical-mediated LP involves a series of reactions, which result in the oxidation of the lipid molecules of free radicals [83]. However, most cells tolerate mild LP by means of their antioxidant defense system [84]. The effects of free radicals on lipids, DNA and proteins are controlled by antioxidant enzymes, namely, SOD, CAT and GPx, as well as by nonenzymatic antioxidants, including the vitamins A, E, C, and glutathione [66], [76], [85], [86]. Oxidative damage to cells and tissues occurs if the reactive oxygen species exceeding the antioxidant capacity of the cell and the primary determinants of the cellular antioxidant defense system are the intermediate and end-products of LP and enzymatic and non-enzymatic antioxidants [53], [75], [87].

The increase in DNA fragmentation reported in the current study was consistent with the previous reports which indicated that AFB1 induce DNA fragmentation [69], [76], [78], [88]. The mutagenicity of AFB1 arising from the toxin molecules which might be forming covalent-adducts resulting in disturb of DNA replication [89]. The formation of AFB1-DNA adducts is regarded as a critical step in the initiation of AFB1-induced hepatocarcinogenesis [54], [90], [91] and p53 gene mutation [92] indicated that oxidative stress is an apoptosis inducer [93].

The current results revealed that administration of both Q and/or CNPs at the two tested doses succeeded to induce a significant improvement in all the tested parameters including the cytokines, procollagen III, antioxidant enzymes, gene expression, oxidative stress markers (MDA and NO) and DNA fragmentation. These findings are in harmony with the previous reports who suggested a protective role of CNPs with a mean diameter of 83.66 nm against H2O2-induced RAW-264.7 cell injury through restoring the activities of endogenous antioxidants (SOD, GPx and CAT), along with enhancement of their gene expression [94]. Although no available report describe the protective role of CNPs against AFB1-induced hepatotoxicity and oxidative stress in liver tissues, the hepatoprotective effect of CS has been documented in several reports. Jeon et al. [95] investigated the antioxidative effect of CS on chronic CCl4-induced hepatic injury in rats and showed that CS has strong antioxidative effects, which decrease TBARS production and increase antioxidant enzyme (catalase and SOD) activities. Moreover, Subhapradha et al. [96] reported that β-Chitosan from Gladius of Sepioteuthis lessoniana has a hepatoprotective effect against CCl4-induced oxidative stress in rats. These authors concluded that in addition to normalizing the oxidative stress markers, β-Chitosan succeeded to normalize plasma AST and ALT levels in CCl4-treated rats which indicate that β-chitosan may stabilize the cell membrane and may prevent a leakage of intracellular enzymes into the blood. Consequently, the overall hepatoprotective effect of CS is probably due to a counteraction of free radicals by its antioxidant nature and/or to its ability to inhibit lipid accumulation by its antilipidemic property [97], [98]. In this concern, Santhosh et al. [99] showed that co-treatment with CS may prevent antitubercular drugs-induced hepatotoxicity in rats. Moreover, CS was also effective against TCDD-induced hepatotoxicity [100] and was proved to protect liver against oxidative damage induced by radiotherapy [101].

On the other hand, the hepatoprotective and antioxidant properties of Q are suggested by Pavanato et al. [102] who found that Q significantly improved all the hepatic toxicity biomarkers in CCl4-induced liver fibrosis in addition to improve liver histology of rats. Moreover, Q was found to modify LPS-induced hepatotoxicity and oxidative stress and protected rat liver against chemicals- or drugs-induced hepatotoxicity [103]. Furthermore, Utesch et al. [104] demonstrated that oral administration of Q did not induce any genotoxic effects in vivo. The hepatoprotective effect of Q was also investigated by Padma et al. [105] who concluded a protective effect against oxidative damage due to its free radical scavenging action and antioxidant nature. In the same respect, Abo-Salem et al. [106] showed that treatment with Q decreased the elevation in biochemical parameters induced by acrylonitrile and it was effective in structural improvement of liver. Another study demonstrated that administration of Q prior to sodium fluoride intoxication prevents hepatotoxicity and oxidative stress in rat liver, probably due to its antioxidant effect [107]. Recently, Tang et al. [108] reported that Q suppressed CYP2E1-dependent ethanol hepatotoxicity. The current results affirmed that, beside the protective role of CNPs alone, it enhanced the antioxidant effect of Q and overcome the problem associated with its poor absorption and bioavailability upon oral administration. In a recent study, Torresa et al. [109] synthesized chitosan-flavonoid conjugate by covalent enzymatic CS modification with Q to enhance the antioxidant and antimicrobial properties and retained thermal degradability. Taken together, the current study indicated that both CNPs and Q alone or in combination succeeded to induce a protective effect against AFB1-induce liver toxicity and carcinogenicity via up-regulating the expression of the antioxidant enzymes. Furthermore, the decrease in DNA fragmentation in the groups treated with CNPs and/or Q suggested that the protective effect of these agents during aflatoxicosis may be resulted from the reduction of apoptosis via the increase in the expression of antioxidants enzymes as well as the free radicals scavenging properties.

5. Conclusion

It could be concluded that exposure to AFB1 resulted in severe oxidative stress and cytotoxicity in the liver typical to that reported in the literature. Co-treatment with Q and/or CNPs at the two tested doses succeeded to mitigation these toxic effects through several mechanisms included the free radical scavenging properties, enhancement of antioxidant capacity, reduction of inflammatory cytokines and modulation of antioxidant gene expression as well as the protection against DNA fragmentation. These effects were more pronounced in the animals treated with the high dose of CNPs plus Q. Consequently, CNPs is a safe and consider a promise candidate for enhancing the role of Q to counteract the health hazards of aflatoxin in the endemic regions.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that we have no financial or non-financial competing interests.

Acknowledgement

This work was supported by National Research Center (Dokki, Cairo, Egypt), Project # 10070112.

References

- 1.Kensler T.W., Roebuck B.D., Wogan G.N., Groopman J.D. Aflatoxin: a 50-year odyssey of mechanistic and translational toxicology. Toxicol. Sci. 2011;120(1):28–48. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfq283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Abbès S., Ben Salah-Abbès J., Abdel-Wahhab M.A., Ouslati R. Immunotoxicological and biochemical effects of aflatoxins in rats prevented by Tunisian montmorillonite with reference to HSCAS. Immunopharmacol. Immunotoxicol. 2010;32(3):514–522. doi: 10.3109/08923970903440176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sun G., Wang S., Hu X., Su J., Zhang Y., Xie Y., Zhang Y., Tang L., Wang J.S. Co-contamination of aflatoxin B1 and fumonisin B1 in food and human dietary exposure in three areas of China. Food Addit. Contam. A: Chem. Anal. Control Expo. Risk Assess. 2011;28(4):461–470. doi: 10.1080/19440049.2010.544678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Abdel-Wahhab M.A., Ibrahim A.A., El-Nekeety A.A., Hassan N.S., Mohamed A.A. Panax ginseng C.A. Meyer extract counteracts the oxidative stress in rats fed multi-mycotoxins-contaminated diet. Com. Sci. 2012;3(3):143–153. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Guengerich F.P., Cai H., McMahon M., Hayes J.D., Sutter T.R., Groopman J.D., Deng Z., Harris T.M. Reduction of aflatoxin B1 dialdehyde by rat and human aldo-keto reductases. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2001;14(6):727–737. doi: 10.1021/tx010005p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mary V.S., Theumer M.G., Arias S.L., Rubinstein H.R. Reactive oxygen species sources and biomolecular oxidative damage induced by aflatoxin B1 and fumonisin B1 in rat spleen mononuclear cells. Toxicology. 2012;302:299–307. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2012.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Theumer M.G., Canepa M.C., Lopez A.G., Mary V.S., Dambolena J.S., Rubinstein H.R. Subchronic mycotoxicoses in Wistar rats: assessment of the in vivo and in vitro genotoxicity induced by fumonisins and aflatoxin B1, and oxidative stress biomarkers status. Toxicology. 2010;268:104–110. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2009.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Josse R., Dumont J., Fautre A., Robin M., Guillouzo A. Identification of early target genes of aflatoxin B1 in human hepatocytes, inter-individual variability and comparison with other genotoxic compounds. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2012;258:176–187. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2011.10.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Somasundaram A., Karthikeyan R., Velmurugan V., Dhandapani B., Raja M. Evaluation of hepatoprotective activity of Kyllinga nemoralis (Hutch & Dalz) rhizomes. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2010;127:555–557. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2009.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fadhel Z.A., Amran S. Effects of black tea extract on carbon tetrachloride-induced lipid peroxidation in liver, kidneys, and testes of rats. Phytother. Res. 2002;16:S28–S32. doi: 10.1002/ptr.793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhang H.S., Zhang M., Yu L.H., Zhao Y., He N.W., Yang X.B. Antitumor activities of quercetin and quercetin-5’,8-disulfonate in human colon and breast cancer cell lines. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2012;29:3451–3460. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2012.01.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.D’Archivio M., Filesi C., Vari R., Scazzocchio B., Masella R. Bioavailability of the polyphenols: status and controversies. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2010;11:1321–1342. doi: 10.3390/ijms11041321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dajas F. Life or death: neuroprotective and anticancer effects of quercetin. J. Ethnopharmcol. 2012;28143(2):383–396. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2012.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Russo G.L., Russo M., Spagnuolo C., Tedesco I., Bilotto S., Iannitti R., Palumbo R. Quercetin: a pleiotropic kinase inhibitor against cancer. Adv. Nutr. Cancer. 2014:185–205. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-38007-5_11. Springer: Berlin, Heidelberg. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Horton J.A., Li F., Chung E.J., Hudak K., White A., Krausz K., Citrin D. Quercetin inhibits radiation-induced skin fibrosis. Rad. Res. 2013;180(2):205–215. doi: 10.1667/RR3237.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hernández-Ortega L.D., Alcántar-Díaz B.E., Ruiz-Corro L.A., Sandoval-Rodriguez A., Bueno-Topete M., Armendariz-Borunda J., Salazar-Montes A.M. Quercetin improves hepatic fibrosis reducing hepatic stellate cells and regulating pro-fibrogenic/antifibrogenic molecules balance. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2012;27(12):1865–1872. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2012.07262.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yu P.X., Zhou Q.J., Zhu W.W., Wu Y.H., Wu L.C., Lin X., Qiu B.T. Effects of quercetin on LPS-induced disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) in rabbits. Thromb. Res. 2013;131(6):270–273. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2013.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hirai I., Okuno M., Katsuma R., Arita N., Tachibana M., Yamamoto Y. Characterisation of anti-Staphylococcus aureus activity of quercetin. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2010;45(6):1250–1254. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pashevin D.A., Tumanovska L.V., Dosenko V.E., Nagibin V.S., Gurianova V.L., Moibenko A.A. Antiatherogenic effect of quercetin is mediated by proteasome inhibition in the aorta and circulating leukocytes. Pharmacol. Rep. 2011;63(4):1009–1018. doi: 10.1016/s1734-1140(11)70617-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ishizawa K., Yoshizumi M., Kawai Y., Terao J., Kihira Y., Ikeda Y., Tamaki T. Pharmacology in health food: metabolism of quercetin in vivo and its protective effect against arteriosclerosis. J. Pharmacol. Sci. 2011;115(4):466–470. doi: 10.1254/jphs.10r38fm. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Perez-Vizcaino F., Bishop-Bailley D., Lodi F., Duarte J., Cogolludo A., Moreno L., Warner T.D. The flavonoid quercetin induces apoptosis and inhibits JNK activation in intimal vascular smooth muscle cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2006;346(3):919–925. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.05.198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Larson A.J., Symons J.D., Jalili T. Therapeutic potential of quercetin to decrease blood pressure: review of efficacy and mechanisms. Adv. Nutr. Int. Rev. J. 2012;3(1):39–46. doi: 10.3945/an.111.001271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yoon J.S., Chae M.K., Lee S.Y., Lee E.J. Anti-inflammatory effect of quercetin in a whole orbital tissue culture of Graves’ orbitopathy. Brit. J. Ophthalmol. 2012;96(8):1117–1121. doi: 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2012-301537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Granado-Serrano A.B., Martín M.Á., Bravo L., Goya L., Ramos S. Quercetin attenuates TNF induced inflammation in hepatic cells by inhibiting the NF-κB pathway. Nutr. Cancer. 2012;64(4):588–598. doi: 10.1080/01635581.2012.661513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chan S.T., Chuang C.H., Yeh C.L., Liao J.W., Liu K.L., Tseng M.J., Yeh S.L. Quercetin supplementation suppresses the secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines in the lungs of Mongolian gerbils and in A549 cells exposed to benzo α pyrene alone or in combination with β-carotene: in vivo and ex vivo studies. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2012;23(2):179–185. doi: 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2010.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bhaskar S., Kumar K.S., Krishnan K., Antony H. Quercetin alleviates hyper-cholesterolemic diet induced inflammation during progression and regression of atherosclerosis in rabbits. Nutrition. 2013;29(1):219–229. doi: 10.1016/j.nut.2012.01.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rice-Evans C.A., Miller N.J., Paganga G. Structure antioxidant activity relationships of flavonoids and phenolic acids. Free Rad. Biol. Med. 1996;e20(7):933–956. doi: 10.1016/0891-5849(95)02227-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Geetha T., Malhotra V., Chopra K., Kaur I.P. Antimutagenic and antioxidant/prooxidant activity of quercetin. Indian J. Exp. Biol. 2005;43(1):61–67. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Needs P.W., Kroon P.A. Convenient syntheses of metabolically important quercetin glucuronides and sulfates. Tetrahedron. 2006;62:6862–6868. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kohda N., Inoue S., Noda T., Saito T. Effects of a chitosan intake on the fecal excretion of dioxins and fat in rats. Biosci. Biotech. Biochemist. 2012;76:1544–1548. doi: 10.1271/bbb.120300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vinsova J., Vavrikova E. Recent advances in drugs and prodrugs design of chitosan. Curr. Pharmacol. Des. 2008;14:1311–1326. doi: 10.2174/138161208799316410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nam K.S., Kim M.K., Shon Y.H. Chemopreventive effect of chitosan oligosaccharide against colon carcinogenesis. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2007;17:1546–1549. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Xu J.G., Xhao X.M., Han X.W., Du Y.G. Antifungal activity of oligochitosan against Phytophthora capsici and other plant pathogenic fungi in vitro. Pest. Biochem. Physiol. 2007;87:220–228. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Je J.Y., Park P.J., Kim S.K. Free radical scavenging properties of heterochitooligosaccharides using an ESR spectroscopy. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2004;42:381–387. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2003.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chen A.S., Taguchi T., Sakai K., Kikuchi K., Wang M.W., Miwa I. Antioxidant activities of chitobiose and chitotriose. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 2003;26:1326–1330. doi: 10.1248/bpb.26.1326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Huang R., Mendis E., Kim S.K. Factors affecting the free radical scavenging behavior of chitosan sulfate. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2005;36:120–127. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2005.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kosaka T., Kaneko Y., Nakada Y., Matsuura M., Tanaka S. Effect of chitosan implantation on activation of canine macrophages and polymorphonuclear cells after surgical stress. J. Vet. Med. Sci. 1996;58:963–967. doi: 10.1292/jvms.58.10_963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ni M.C., Dunshea-Mooij C.A., Bennett D., Rodgers A. Chitosan for overweight or obesity. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2005;2005(3):CD003892. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003892.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hossain S., Rahman A., Kabir Y., Shams A.A., Afros F., Hashimoto M. Effects of shrimp (Macrobrachium rosenbergii)-derived chitosan on plasma lipid profile and liver lipid peroxide levels in normo- and hypercholesterolaemic rats. Clin. Exp. Pharmacol. Physiol. 2007;34(3):170–176. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1681.2007.04568.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sumiyoshi M., Kimura Y. Low molecular weight chitosan inhibits obesity induced by feeding a high-fat diet long-term in mice. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 2006;58(2):201–207. doi: 10.1211/jpp.58.2.0007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jia L. Nanoparticle formulation increases oral bioavailability of poorly soluble drugs: approaches experimental evidences and theory. Curr. Nanosci. 2005;1(3):237. doi: 10.2174/157341305774642939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Müller R.H., Böhm B.H.L. Medpharm Scientific Publishers; Stuttgart, Germany: 1998. Emulsions and Nanosuspensions for the Formulation of Poorly Soluble Drugs; pp. 149–174. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tang Z.X., Qian J.Q., Shi L.E. Preparation of chitosan nanoparticles as carrier for immobilized enzyme. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2007;136(1):77–96. doi: 10.1007/BF02685940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lin C.C., Hsu Y.F., Lin T.C., Hsu F.L., Hsu H.Y. Antioxidant and hepatoprotective activity of Punicalagin and Punicalin on carbon tetrachloride-induced liver damage in rats. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 1998;50(7):789–794. doi: 10.1111/j.2042-7158.1998.tb07141.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Limaye P.V., Raghuram N., Sivakami S. Oxidative stress and gene expression of antioxidant enzymes in the renal cortex of streptozotocin induced diabetic rats. Mol. Cell Biochem. 2003;243:147–152. doi: 10.1023/a:1021620414979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Raben N., Nichols R.C., Martiniuk F., Plotz P.H. A model of mRNA splicing in adult lysosomal storage disease (glycogenosis type II) Hum. Mol. Genet. 1996;5:995–1001. doi: 10.1093/hmg/5.7.995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wu B., Iwakiri R., Ootani A., Tsunada S., Ujise T., Skata H., Toda S., Fujimoto K. Dietary corn oil promotes colon cancer by inhibiting mitochondria dependent apoptosis in azoxymethane-treated rats. Exp. Biol. Med. (Maywood) 2004;299:1017–1025. doi: 10.1177/153537020422901005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Duncan B.D. Multiple range tests for correlated and heteroscedastic means. Biometrics. 1957;13:359–364. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Antoniou J., Liu F., Majeed H., Qi J., Yokoyama W., Zhong F. Physicochemical and morphological properties of size-controlled chitosan-tripolyphosphate nanoparticles. Colloids Surf. A: Physicochem. Eng. 2015;465:137–146. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tang Z.X., Shi L.E., Qian J.Q. Neutral lipase from aqueous solutions on chitosan nano-particles. Biochem. Eng. J. 2007;34:217–223. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Fahima A., Kheireddine S., Belaaouad Sodium tripolyphosphate (STPP) as a novel corrosion inhibitor for mild steel in 1 M HCl. J. Optoelectron. Adv. Mater. 2013;15:451–456. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Adeleye A.O., Ajiboye T.O., Iliasu G.A., Abdussalam F.A., Balogun A., Ojewuyi O.B., Yakubu M.T. Phenolic extract of Dialium guineense pulp enhances reactive oxygen species detoxification in aflatoxin B1 hepatocarcinogenesis. J. Med. Food. 2014;17(8):875–885. doi: 10.1089/jmf.2013.0157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.El-Nekeety A.A., Abdel-Azeim S.H., Hassan A.M., Hassan N.S., Aly S.E., Abdel-Wahhab M.A. Quercetin inhibits the cytotoxicity and oxidative stress in liver of rats fed aflatoxin-contaminated diet. Toxicol. Rep. 2014;1:319–329. doi: 10.1016/j.toxrep.2014.05.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Abdel-Wahhab M.A., Ahmed H.H., Hagazi M.M. Prevention of aflatoxin B1-initiated hepatotoxicity in rat by marine algae extracts. J Appl. Toxicol. 2006;26(3):229–238. doi: 10.1002/jat.1127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Choi K.C., Chung W.T., Kwon J.K., Jang Y.S., Yu J.Y., Park S.M., Lee J.C. Chemoprevention of a flavonoid fraction from Rhus verniciflua Stokes on aflatoxin B1-induced hepatic damage in mice. J. Appl. Toxicol. 2011;31(2):150–156. doi: 10.1002/jat.1575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Moon Y.J., Wang X., Morris M.E. Dietary flavonoids: effects on xenobiotic and carcinogen metabolism. Toxicol. In Vitro. 2006;20(2):187–210. doi: 10.1016/j.tiv.2005.06.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Suganuma M., Sueoka E., Sueoko N., Okabe S., Fujiki H. Mechanisms of cancer prevention by tea polyphenols based on inhibition of TNF-alpha expression. Biofactors. 2000;13:67–72. doi: 10.1002/biof.5520130112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Karabela S.P., Kairi C.A., Magkouta S., Psallidas I., Moschos C., Stathopoulos I., Zakynthinos S.G., Roussos C., Kalomenidis I., Stathopoulos G.T. Neutralization of tumor necrosis factor bioactivity ameliorates urethane-induced pulmonary oncogenesis in mice. Neoplasia. 2011;13(12):1143–1151. doi: 10.1593/neo.111224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Akçam M., Artan R., Yilmaz A., Ozdem S., Gelen T., Nazıroğlu M. Caffeic acid phenethyl ester modulates aflatoxin B1-induced hepatotoxicity in rats. Cell Biochem. Funct. 2013;31(8):692–6927. doi: 10.1002/cbf.2957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Bianco G., Russo R., Marzocco S., Velotto S., Autore G., Severino L. Modulation of macrophage activity by aflatoxins B1 and B2 and their metabolites aflatoxins M1 and M2. Toxicon. 2012;59(6):644–650. doi: 10.1016/j.toxicon.2012.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Moon E.Y., Rhee D.K., Pyo S. Alteration of kinase-mediated signalings in murine peritoneal macrophages by aflatoxin B1. Cancer Lett. 2000;155(1):9–17. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3835(00)00363-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Azeredo-Martins A.K., Lortz S., Lenzen S., Curi R., Eizirik D.L., Tiedge M. Improvement of the mitochondrial antioxidant defense status prevents cytokine induced nuclear factor-kappa B activation in insulin-producing cells. Diabetes. 2003;52:93–101. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.52.1.93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Leonardi S., La Spina M., La Rosa M., Schiliro G. Polyhydroxylase and procollagen type III in long-term survivors of acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL): a biochemical approach to HCV-related liver disease. Med. Pediatr. Oncol. 2003;41:17–20. doi: 10.1002/mpo.10309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Han S.H., Jeon Y.J., Yea S.S., Yang K.H. Suppression of the interleukin-2 gene expression by aflatoxin B1 is mediated through the down-regulation of the NF-AT and AP-1 transcription factors. Toxicol. Lett. 1999;108(1):1–10. doi: 10.1016/s0378-4274(99)00008-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Barton C.C., Barton E.X., Ganey P.E., Kunkel S.L., Roth R.A. Bacterial lipopolysaccharide enhances aflatoxin B1 hepatotoxicity in rats by a mechanism that depends on tumor necrosis factor alpha. Hepatology. 2001;33(1):66–73. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2001.20643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.El-Bahr S.M. Effect of curcumin on hepatic antioxidant enzymes activities and gene expressions in rats intoxicated with aflatoxin B1. Phytother. Res. 2015;29(1):134–140. doi: 10.1002/ptr.5239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.El-Nekeety A.A., Mohamed S.R., Hathout A.S., Hassan N.S., Aly A.E., Abdel-Wahhab M.A. Antioxidant properties of Thymus vulgaris oil against aflatoxin-induce oxidative stress in male rats. Toxicon. 2011;57:984–991. doi: 10.1016/j.toxicon.2011.03.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Abbès S., Ben Salah-Abbès J., Jebali R., Younes R.B., Oueslati R. Interaction of aflatoxin B1 and fumonisin B1 in mice causes immunotoxicity and oxidative stress: possible protective role using lactic acid bacteria. J. Immunotoxicol. 2015;14:1–9. doi: 10.3109/1547691X.2014.997905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Ajiboye T.O., Yakubu M.T., Oladiji A.T. Lophirones B and C extenuate AFB1-mediated oxidative onslaught on cellular proteins, lipids, and DNA through Nrf-2 expression. J. Biochem. Mol. Toxicol. 2014;28(12):558–567. doi: 10.1002/jbt.21598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Shen H., Liu J., Wang Y., Lian H., Wang J., Xing L., Yan X., Wang J., Zhang X. Aflatoxin G1-induced oxidative stress causes DNA damage and triggers apoptosis through MAPK signaling pathway in A549 cells. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2013;62:661–669. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2013.09.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Abdel-Wahhab M.A., Hassan N.S., El-Kady A.A., Mohamed Y.A., El-Nekeety A.A., Mohamed S.R., Sharaf H.A., Mannaa F.A. Red ginseng protects against aflatoxin B1 and fumonisin-induced hepatic pre-cancerous lesions in rats. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2010;48(2):733–742. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2009.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Corcuera L.A., Vettorazzi A., Arbillaga L., Pérez N., Gil A.G., Azqueta A., González-Peñas E., García-Jalón J.A., López de Cerain A. Genotoxicity of Aflatoxin B1 and Ochratoxin A after simultaneous application of the in vivo micronucleus andcomet assay. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2015;76C:116–124. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2014.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Jiang M., Peng X., Fang J., Cui H., Yu Z., Chen Z. Effects of aflatoxin B1 on T-cell subsets and mRNA expression of cytokines in the intestine of broilers. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2015;16(4):6945–6959. doi: 10.3390/ijms16046945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.He Y., Fang J., Peng X., Cui H., Zuo Z., Deng J., Chen Z., Lai W., Shu G., Tang L. Effects of sodium selenite on aflatoxin B1-induced decrease of ileac T cell and the mRNA contents of IL-2, IL-6, and TNF-α in broilers. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 2014;159(1-3):167–173. doi: 10.1007/s12011-014-9999-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Abdel-Azeim S.H., Hassan A.M., El-Denshary A.S., Hamzawy M.A., Mannaa F.A., Abdel-Wahhab M.A. Ameliorative effects of thyme and calendula extracts alone or in combination against aflatoxins-induced oxidative stress and genotoxicity in rat liver. Cytotechnology. 2014;66(3):457–470. doi: 10.1007/s10616-013-9598-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Hassan A.M., Abdel-Azeim S.H., El-Nekeety A.A., Abdel-Wahhab M.A. Panax ginseng extract modulates oxidative stress, DNA fragmentation and up-regulate gene expression in rats sub chronically treated with aflatoxin B1 and fumonisin B1. Cytotechnology. 2014 doi: 10.1007/s10616-014-9726-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Alam K., Nagi M.N., Badary O.A., Al-Shabanah O.A., Al-Rikabi A.C., Al-Bekairi A.M. The protective action of thymol against carbon tetrachloride hepatotoxicity in mice. Pharmacol. Res. 1999;40:159–163. doi: 10.1006/phrs.1999.0472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Hassan A.M., Abdel-Aziem S.H., Abdel-Wahhab M.A. Modulation of DNA damage and alteration of gene expression during aflatoxicosis via dietary supplementation of Spirulina (Arthrospira) and whey protein concentrate. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Safety. 2012;79:294–300. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoenv.2012.01.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Techapiesancharoenkij N., Fiala J.L., Navasumrit P., Croy R.G., Wogan G.N., Groopman J.D., Ruchirawat M., Essigmann J.M. Sulforaphane, a cancer chemopreventive agent, induces pathways associated with membrane biosynthesis in response to tissue damage by aflatoxin B1. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2015;282(1):52–60. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2014.11.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Choi K.C., Chung W.T., Kwon J.K., Yu J.Y., Jang Y.S., Park S.M., Lee S.Y., Lee J.C. Inhibitory effects of quercetin on aflatoxin B1-induced hepatic damage in mice. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2010;48(10):2747–2753. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2010.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Shen H.M., Ong C.N., Shi C.Y. Involvement of reactive oxygen species in aflatoxin B1-induced cell injury in cultured rat hepatocytes. Toxicology. 1995;99:115–123. doi: 10.1016/0300-483x(94)03008-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Gueraud F., Atalay M., Bresgen N., Cipak A., Eckl P.M., Huc L., Jouanin I., Siems W., Uchida K. Chemistry and biochemistry of lipid peroxidation products. Free Radic. Res. 2010;44:1098–1124. doi: 10.3109/10715762.2010.498477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Niki E. Lipid peroxidation: physiological levels and dual biological effects. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2009;47:469–484. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2009.05.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Zadak Z., Hyspler R., Ticha A., Hronek M., Fikrova P., Rathouska J., Hrnciarikova D., Stetina R. Antioxidants and vitamins in clinical conditions. Physiol. Res. 2009;58:13–17. doi: 10.33549/physiolres.931861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Singh K.B., Maurya B.K., Trigun S.K. Activation of oxidative stress and inflammatory factors could account for histopathological progression of aflatoxin-B1 induced hepatocarcinogenesis in rat. Mol. Cell Biochem. 2015;401(1–2):185–196. doi: 10.1007/s11010-014-2306-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Fito M., De la Torre R., Covas M.I. Olive oil and oxidative stress. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2007;51:1215–1224. doi: 10.1002/mnfr.200600308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Sirajudeen M., Gopi K., Tyagi J.S., Moudgal R.P., Mohan J., Singh R. Protective effects of melatonin in reduction of oxidative damage and immunosuppression induced by aflatoxin B1-contaminated diets in young chicks. Environ. Toxicol. 2011;26:153–160. doi: 10.1002/tox.20539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Abdel-Wahhab M.A., Nada S.A., Farag I.M., Abbas N.F., Amra H.A. Potential protective effect of HSCAS and Bentonite against dietary aflatoxicosis in rat: with special reference to chromosomal aberrations. Nat. Toxins. 1998;6:211–218. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1522-7189(199809/10)6:5<211::aid-nt31>3.0.co;2-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Bonnett M., Taylor E.R. The structure of the aflatoxin B1-DNA adduct at N7 of guanine. Theoretical intercalation and covalent adduct models. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 1989;7:127–149. doi: 10.1080/07391102.1989.10507756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Pfohl-Leszkowicz A. Formation, persistence and significance of DNA adduct formation in relation to some pollutants from a board perspective. Adv. Toxicol. 2008;2:183–240. [Google Scholar]

- 91.Preston R.J., Williams G.M. DNA-reactive carcinogens: mode of action and human cancer hazard. Crit. Rev. Toxicol. 2005;35:673–683. doi: 10.1080/10408440591007278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Habib S.L., Said B., Awad A.T., Mostafa M.H., Shank R.C. Novel adenine adducts, N7-guanine-AFB1 adducts, and p53 mutationsin patients with schistosomiasis and aflatoxin exposure. Cancer Detect. Prev. 2006;30:491–498. doi: 10.1016/j.cdp.2006.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Meki A.M., Esmail E.F., Hussein A.A., Hassanein H.M. Caspase-3 and heat shock protein-70 in rat liver treated with aflatoxin B1: effect of melatonin. Toxicon. 2004;43:93–100. doi: 10.1016/j.toxicon.2003.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Wen Z.S., Liu L.J., Qu Y.L., OuYang X.K., Yang L.Y., Xu Z.R. Chitosan nanoparticles attenuate hydrogen peroxide-induced stress injury in mouse macrophage RAW264 7 cells. Mar. Drugs. 2013;11(10):3582–3600. doi: 10.3390/md11103582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Jeon T.I., Hwang S.G., Park N.G., Jung Y.R., Shin S.I., Choi S.D., Park D.K. Antioxidative effect of chitosan on chronic carbon tetrachloride induced hepatic injury in rats. Toxicology. 2003;187(1):67–73. doi: 10.1016/s0300-483x(03)00003-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Subhapradha N., Saravanan R., Ramasamy P., Srinivasan A., Shanmugam V., Shanmugam A. Hepatoprotective effect of β-Chitosan from Gladius of Sepioteuthis lessoniana against carbon tetrachloride-induced oxidative stress in Wistar rats. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2013:1–12. doi: 10.1007/s12010-013-0499-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Sivakumar R., Rajesh R., Buddhan S., Jeyakum R., Rajaprabhu D., Ganesan B., Anandan R. Antilipidemic effect of chitosan against experimentally induced myocardial infarction in rats. J. Cell Anim. Biol. 2007;1(4):071–077. [Google Scholar]

- 98.Ramasamy P., Subhapradha N., Shanmugam V., Shanmugam A. Protective effect of chitosan from Sepia kobiensis (Hoyle 1885) cuttlebone against CCl4 induced hepatic injury. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2014;65:559–563. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2014.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Santhosh S., Sini T.K., Anandan R., Mathew P.T. Effect of chitosan supplementation on antitubercular drugs-induced hepatotoxicity in rats. Toxicology. 2006;219(1):53–59. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2005.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.El-Fattah H.M.A., Abdel-Kader Z.M., Hassnin E.A., El-Rahman M.K.A., Hassan L.E. Chitosan as a hepato-protective agent against single oral dose of dioxin. IOSR J. Env. Sci. Toxicol. Food Technol. (IOSR-JESTFT) 2013;7(3):11–17. [Google Scholar]

- 101.Mohamed N.E. Effect of chitosan on oxidative stress and metabolic disorders induced in rats exposed to radiation. J. Am. Sci. 2011;7(6):406–417. [Google Scholar]

- 102.Pavanato A., Tuñón M.J., Sánchez-Campos S., Marroni C.A., Llesuy S., González-Gallego J., Marroni N. Effects of quercetin on liver damage in rats with carbon tetrachloride-induced cirrhosis. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2003;48(4):824–829. doi: 10.1023/a:1022869716643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Kebieche M., Lakroun Z., Lahouel M., Bouayed J., Meraihi Z. Evaluation of epirubicin-induced acute oxidative stress toxicity in rat liver cells and mitochondria, and the prevention of toxicity through quercetin administration. Exp. Toxicol. Pathol. 2009;61:161–167. doi: 10.1016/j.etp.2008.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Utesch D., Feige K., Dasenbrock J., Broschard T.H., Harwood M., Danielewska-Nikiel B., Lines T.C. Evaluation of the potential in vivo genotoxicity of quercetin. Mutat. Res. Genet. Toxicol. Environ. Mutagen. 2008;654:38–44. doi: 10.1016/j.mrgentox.2008.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Padma V.V., Baskaran R., Roopesh R.S., Poornima P. Quercetin attenuates lindane induced oxidative stress in Wistar rats. Mol. Boil. Rep. 2012;39(6):6895–6905. doi: 10.1007/s11033-012-1516-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Abo-Salem O.M., Abd-Ellah M.F., Ghonaim M.M. Hepatoprotective activity of quercetin against acrylonitrile-induced hepatotoxicity in rats. J. Biochem. Mol. Toxicol. 2011;25(6):386–392. doi: 10.1002/jbt.20406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Nabavi S.M., Nabavi S.F., Eslami S., Moghaddam A.H. In vivo protective effects of quercetin against sodium fluoride-induced oxidative stress in the hepatic tissue. Food Chem. 2012;132(2):931–935. [Google Scholar]

- 108.Tang Y., Tian H., Shi Y., Gao C., Xing M., Yang W., Yao P. Quercetin suppressed CYP2E1-dependent ethanol hepatotoxicity via depleting heme pool and releasing CO. Phytomedicine. 2013;20(8):699–704. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2013.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Torresa E., Marrin V., Aburto J., Beltrȁn H.I., Shirai K., Villanueva S., Sandoval G. Enzymatic modification of chitosan with quercetin and its application as antioxidant edible films. Appl. Biochem. Microbiol. 2012;48(2):151–158. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]