Abstract

Objective

To characterize the use of venous thromboembolism prophylaxis during antepartum and postpartum hospitalizations in the United States.

Methods

A retrospective cohort study using the Perspective database was performed to analyze temporal trends of mechanical and pharmacologic venous thromboembolism prophylaxis for patients hospitalized for antepartum and postpartum indications between 2006 and 2015.Delivery hospitalizations were excluded. The association between use of prophylaxis and medical and obstetric risk factors, as well as patient demographic and hospital characteristics was evaluated with unadjusted and adjusted models, accounting for demographic, hospital, and medical, and obstetric risk factors.

Results

Six hundred twenty-two thousand seven hundred forty antepartum and 105,361 postpartum readmissions were identified and included in the analysis. Between 2006 and 2015, use of venous thromboembolism prophylaxis increased from 18.5% to 38.7% for antepartum admissions,(adjusted relative risk 1 1.94, 95% CI 1.88-2.01) and from 22.5% to 30.6% for postpartum readmissions (adjusted RR 1.31, 95% CI 1.21-1.43). Among women readmitted postpartum 56.4% of prophylaxis was pharmacologic and 43.6% was mechanical. For antepartum admissions, 87.2% of prophylaxis was mechanical and 12.8% was pharmacologic. Significant regional and hospital-level variation was noted, with prophylaxis most common in the South. In both unadjusted and unadjusted analyses, use of venous thromboembolism prophylaxis was more common for women with thrombophilia, ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome, history of venous thromboembolism, and prolonged hospitalization. Factors associated with decreased rates of prophylaxis included hyperemesis and postpartum endometritis.

Conclusion

While antepartum and postpartum venous thromboembolism prophylaxis is becoming increasingly common, particularly in the setting of medical or obstetric risk factors, use of prophylaxis varies regionally and on a hospital level. Some risk factors for venous thromboembolism were associated with lower rates of prophylaxis. The heterogeneity of clinical approaches to venous thromboembolism prophylaxis for these patient populations may represent an opportunity to perform outcomes research to further clarify best practices.

Introduction

Obstetric venous thromboembolism is a leading cause of maternal morbidity and mortality in the United States and other developed countries, accounting for 9.3% of pregnancy-related deaths from 2006 to 2010 according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).2 Antepartum and postpartum hospitalizations may place patients at particularly high risk for venous thromboembolism events. A study of venous thromboembolism during antepartum admissions in England found that the risk for events was 17.5-fold higher when patients were hospitalized versus outpatient with risk particularly high for patients hospitalized 3 days or longer.3 The postpartum period is also associated with increased risk for venous thromboembolismevents4 particularly in the setting of common indications for readmission such as infection, hemorrhage, and preeclampsia.5 In the United States, venous thromboembolism during antepartum and postpartum hospitalizations has risen,6 with the CDC estimating that the rate of thrombotic embolism during postpartum hospitalizations increased 169% between 1998 and 2009 from 1.33 to 3.57 events per 10,000 delivery hospitalizations.7

Recommendations for venous thromboembolism prophylaxis during non-delivery (antepartum and postpartum)hospitalizations from major societies vary.8 While the American College of Chest Physicians (ACCP)9,10 and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (the College)11 recommend prophylaxis for the highest risk patients, such as those with prior venous thromboembolism events, thrombophilia, or both, recommendations for non-delivery hospitalizations are otherwise nonspecific. In comparison, both the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (RCOG)12 and the National Partnership for Maternal Safety (NPMS)13 support prophylaxis for antepartum hospitalizations absent a contraindication. RCOG supports prophylaxis for postpartum readmissions.

We have previously reported that thromboembolism prophylaxis during cesarean hospitalizations is increasing while prophylaxis during vaginal deliveries is rare.14,15 Given that practice patterns in administering venous thromboembolism prophylaxis in the United States for non-delivery obstetric hospitalizations are unknown and that major society recommendations are divergent, the objective of this study was to characterize use of venous thromboembolism prophylaxis during antepartum and postpartum hospital readmissions in the United States.

Materials and Methods

This analysis used the Perspective database, maintained by Premier Incorporated (Charlotte, NC). In addition to demographic data and discharge and procedure codes, Perspective includes information on devices and medications received by patients during acute care hospitalizations at more than 600 hospitals across the United States. Community and academic, teaching and non-teaching hospitals are included. Hospitals included in the database report data on 100% of hospitalizations. The data undergo 95 quality assurance and validation checks prior to being used for research.16 Perspective is routinely used for outcomes based research including analyses of thromboembolism prophylaxis across a number of specialties including obstetrics.17-22 Discharges in the Perspective database represent approximately 15% of inpatient hospital stays annually. Hospitals in Perspective contribute data voluntarily; data are not representative of national admissions. However, weighting files within Perspective are available to provide nationally representative estimates based on the Perspective's data. All data were de-identified and the study was approved by the Columbia University Institutional Review Board.

Inclusion criteria included women hospitalized for a postpartum or antepartum indication from January 2006 through March 2015. Antepartum and postpartum hospitalizations were identified based on International Statistical Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) diagnosis codes. The specific algorithm used to identify antepartum and postpartum hospitalizations was provided by the CDC.7 For antepartum hospitalizations, only hospitalizations ≥3 days were included given that this length of antepartum hospitalization is associated with higher risk for venous thromboembolism events.3 All postpartum hospitalizations were included. Women with ICD-9-CM codes for acute venous thromboembolism (deep vein thrombosis, pulmonary embolism, or both) were excluded. Women with a code for a delivery hospitalization (ICD-9-CM 650 or V27.x) were similarly excluded.

The primary outcome was receipt of venous thromboembolism prophylaxis. Drug and device charge codes were analyzed to determine if women received pharmacologic prophylaxis (unfractionated heparin [UFH], low molecular weight heparin [LMWH], fondaparinux) or mechanical prophylaxis [sequential compression devices, graduated compression stockings, other pneumatic devices]).LMWH included enoxaparin sodium, tinzaparin sodium and dalteparin sodium. Our search methodology for drugs and devices included identifying common misspellings of drugs and medications to improve ascertainment.

After reviewing epidemiologic literature, obstetric and medical factors associated with obstetric venous thromboembolism were included in the analysis.23-29 Antepartum risk factors included ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome, hyperemesis, infection (pyelonephritis, pneumonia, influenza, SIRS, and sepsis),and multiple gestation, among other conditions. Postpartum risk factors included endometritis, postpartum hemorrhage or transfusion, and preeclampsia, eclampsia or gestational hypertension, along with other conditions. Hospital characteristics included location (urban versus rural), teaching status (teaching versus nonteaching), geographic region (Midwest, Northeast, South, West) and hospital size based on number of beds (fewer than 400, 400 to 600, or greater than 600 beds). Demographic factors included maternal age, marital status, race, and year of hospitalization.

All analyses were performed separately for antepartum and postpartum hospitalizations. The associations between thromboembolism prophylaxis and clinical, hospital, and demographic variables were compared using the Chi-square test. In evaluating Chi-square test results, the p-values are almost always statistically significant; these findings do not necessarily represent clinically significance associations. Unadjusted hospital rates of prophylaxis were calculated. Given the cohort nature of the data, we developed log-linear regression models to account for the influence of clinical, demographic, and hospital factors on use of prophylaxis. From these models, we estimated the risk ratio (RR) with 95% confidence interval (CI) as measures of effect. For the Perspective database, weights can be applied to the data to create national estimates. We performed a sensitivity analysis applying weights to the data used to calculate temporal trends to estimate the prevalence of prophylaxis in the United States. All analyses were performed with SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Results

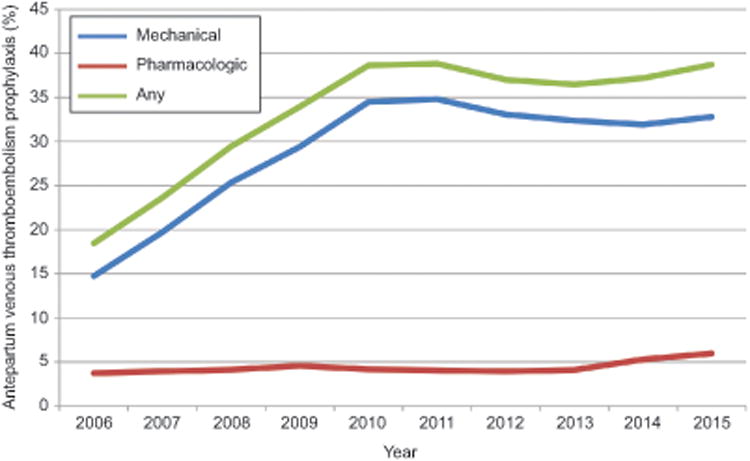

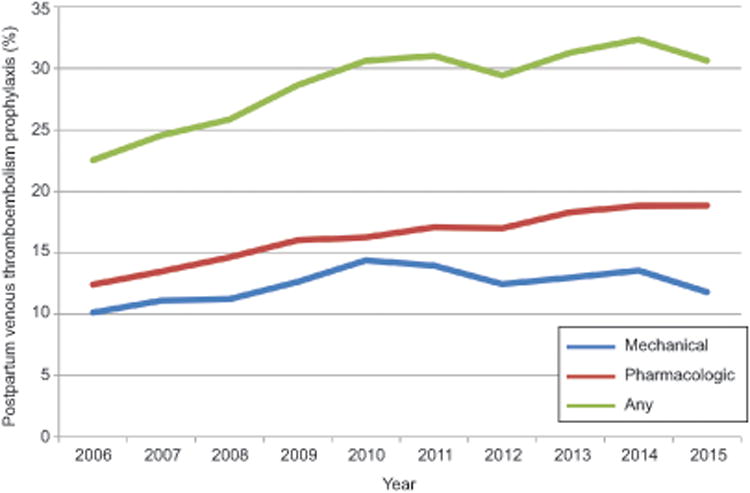

Six hundred twenty-two thousand seven hundred forty antepartum admissions from 628 hospitals and 105,361 postpartum readmissions from 611 hospitals from 2006 through March 2015 were included in the analysis. Overall, 33.2% of antepartum admissions (n=206,836) and 28.8% of postpartum readmissions (n=30,340) received venous thromboembolism prophylaxis. Rates of pharmacologic versus mechanical venous thromboembolism prophylaxis by year for antepartum and postpartum prophylaxis are demonstrated in Figure 1 and Figure 2 respectively. Over the study period, prophylaxis generally increased with 18.5% of antepartum admissions receiving prophylaxis in 2006 versus 38.7% in 2015, and 22.5% of postpartum readmissions receiving prophylaxis in 2006 versus 30.6% in 2015. Pharmacologic prophylaxis was more common among postpartum hospitalizations than antepartum hospitalizations; 56.4% of hospitalized postpartum patients who received some form of venous thromboembolism prophylaxis received UFH or LMWH versus 12.8% of antepartum admissions.

Figure 1.

The figure demonstrates probability of mechanical, pharmacologic, or any prophylaxis by year from 2006 through the first quarter of 2015 for antepartum admissions. Pharmacologic prophylaxis included unfractionated heparin and low molecular weight heparin and fondaparinux. Mechanical prophylaxis included sequential compression devices, graduated compression stockings, and other pneumatic devices.

Figure 2.

The figure demonstrates probability of mechanical, pharmacologic, or any prophylaxis by year from 2006 through the first quarter of 2015 for postpartum admissions. Pharmacologic prophylaxis included unfractionated heparin and low molecular weight heparin and fondaparinux. Mechanical prophylaxis included sequential compression devices, graduated compression stockings, and other pneumatic devices

Table 1 demonstrates obstetric, medical, and demographic figures associated with venous thromboembolism prophylaxis for antepartum admissions and postpartum readmissions. Prophylaxis rates varied significantly by region: Rates of antepartum and postpartum prophylaxis in the South were highest (43.2% and 32.7%, respectively) compared to the Northeast (27.6%, 21.6%), Midwest (30.8%, 30.8%), and West (23.3%, 23.3%) (p<0.01). Longer length of stay was associated with higher rates of prophylaxis. For antepartum admissions, 32.1% of women hospitalized 3-6 days received prophylaxis whereas 39.3% of women hospitalized ≥7 days received prophylaxis (p<0.01). For postpartum readmissions, rates of prophylaxis were 18.6% for 1-day admissions, 20.6% for 2-day admissions, and 41.0% for admissions ≥3 days (p<0.01).Patients with medical conditions that placed them at very high risk for venous thromboembolism were more likely to receive prophylaxis. 71.2% of antepartum admissions for ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome received prophylaxis. Among women with history of venous thromboembolism, 87.6% received prophylaxis during antepartum admissions and 69.9% received prophylaxis during postpartum readmissions. Women with thrombophilia were also more likely to receive prophylaxis; 84.3% of women with this diagnosis received prophylaxis during an antepartum admission versus 77.8% during a postpartum readmission. Women with thrombophilia and history of venous thromboembolism were more likely to receive pharmacologic as opposed to mechanical prophylaxis compared to the rest of the cohort. During antepartum admissions 84.9% of prophylaxis for women with prior venous thromboembolism and 80.7% of prophylaxis for women with thrombophilia was pharmacologic. During postpartum readmissions 86.0% of prophylaxis for women with prior venous thromboembolism and 88.9% of prophylaxis for women with thrombophilia was pharmacologic. Risk factors associated with lower rates of prophylaxis included hyperemesis (20.1% during antepartum hospitalizations) and postpartum endometritis (22.2%).For antepartum hospitalizations, 26.3% of hospitals had a prophylaxis rate of <20%, 26.3% had a rate of 20% to <30%, 22.5% had a rate of 30% to <40%, and 25.0% had a rate of ≥40%. For postpartum hospitalizations, 27.1% of hospitals had a prophylaxis rate of <20%, 26.2% had a rate of 20% to <30%, 22.4% had a rate of 30% to <40%, and 24.2% had a rate of ≥40%.

Table 1. Proportion of antepartum admissions and postpartum readmissions receiving thromboembolism prophylaxis.

| Antepartum | Postpartum | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Prophylaxis, n (%) | No prophylaxis, n (%) | Prophylaxis, n (%) | No prophylaxis, n (%) | |

|

| ||||

| All patients | 206,836 (33.2%) | 415,904 (66.7%) | 30,340 (28.8%) | 75,021 (71.2%) |

| Year | ||||

| 2006 | 10,982 (18.5%) | 48,498 (81.5%) | 2,185 (22.5%) | 7,510 (77.5%) |

| 2007 | 14,715 (23.6%) | 47,514 (76.4%) | 2,514 (24.6%) | 7,724 (75.4%) |

| 2008 | 18,444 (29.4%) | 44,189 (70.6%) | 2,634 (25.8%) | 7,558 (74.2%) |

| 2009 | 21,210 (33.9%) | 41,281 (66.1%) | 3,109 (28.7%) | 7,744 (71.3%) |

| 2010 | 25,232 (38.6%) | 40,067 (61.4%) | 3,414 (30.6%) | 7,734 (69.4%) |

| 2011 | 28,340 (38.8%) | 44,629 (61.2%) | 3,782 (31.0%) | 8,407 (69.0%) |

| 2012 | 29,652 (37.0%) | 50,478 (63.0%) | 3,962 (29.4%) | 9,500 (68.7%) |

| 2013 | 27,054 (36.5%) | 47,145 (63.5%) | 4,142 (31.3%) | 9,102 (68.7%) |

| 2014 | 25,492 (37.2%) | 43,061 (62.8%) | 3,839 (32.4%) | 8,024 (67.6%) |

| 2015 (first quarter) | 5,715 (38.7%) | 9,042 (61.3%) | 759 (30.6%) | 1,718 (69.4%) |

| Hospital bed size | ||||

| <400 | 97,272 (32.7%) | 200,181 (67.3%) | 15,093 (28.2%) | 38,510 (71.8%) |

| 400-600 | 53,187 (31.3%) | 116,927 (68.7%) | 7,873 (27.5%) | 20,802 (72.5%) |

| >600 | 56,377 (36.3%) | 98,796 (63.7%) | 7,374 (32.0%) | 15,709 (86.0%) |

| Age (years) | ||||

| 15-17 | 4,484 (26.1%) | 12,668 (73.9%) | 262 (18.8%) | 1,133 (81.2%) |

| 18-24 | 53,351 (31.9%) | 114,019 (68.1%) | 8,983 (27.9%) | 23,204 (72.1%) |

| 25-29 | 54,284 (34.0%) | 105,574 (66.0%) | 7,876 (28.5%) | 19,803 (71.5%) |

| 30-34 | 53,326 (34.1%) | 102,849 (65.9%) | 7,065 (29.4%) | 16,966 (70.6%) |

| 35-39 | 31,682 (34.0%) | 61,622 (66.0%) | 4,258 (30.6%) | 9,663 (69.4%) |

| ≥40 | 9,709 (33.6%) | 19,172 (66.4%) | 1,501 (34.1%) | 2,894 (65.9%) |

| Insurance status | ||||

| Medicare | 2,824 (33.9%) | 5,503 (66.1%) | 647 (34.0%) | 1,259 (66.0%) |

| Medicaid | 80,768 (32.5%) | 167,489 (67.5%) | 15,051 (29.5%) | 35,961 (70.5%) |

| Private | 112,127 (33.6%) | 221,667 (66.4%) | 12,446 (28.1%) | 31,915 (71.9%) |

| Other | 6,804 (34.9%) | 12,710 (65.1%) | 1,085 (29.2%) | 2,627 (70.7%) |

| Uninsured | 4,313 (33.6%) | 8,535 (66.4%) | 1,111 (25.4%) | 3,259 (74.6%) |

| Race | ||||

| White | 116,178 (36.3%) | 203,869 (63.7%) | 15,200 (29.3%) | 36,751 (70.7%) |

| Black | 39,993 (36.4%) | 69,953 (63.6%) | 7,758 (32.4%) | 16,218 (67.6%) |

| Hispanic | 8,668 (27.4%) | 22,909 (72.6%) | 1,475 (26.3%) | 4,137 (73.7%) |

| Other | 41,867 (26.0%) | 119,003 (74.0%) | 5,897 (24.8%) | 17,865 (75.2%) |

| Unknown | 130 (43.3%) | 170 (56.7%) | 10 (16.7%) | 50 (83.3%) |

| Hospital Location | ||||

| Rural | 11,110 (30.6%) | 25,247 (69.4%) | 2,653 (29.5%) | 6,344 (70.5%) |

| Urban | 195,726 (33.4%) | 390,657 (66.6%) | 27,687 (28.7%) | 68,677 (71.3%) |

| Marital Status | ||||

| Married | 101,960 (35.1%) | 188,750 (64.9%) | 12,413 (28.9%) | 30,579 (71.1%) |

| Unmarried | 86,469 (34.4%) | 164,739 (65.6%) | 14,539 (29.6%) | 34,665 (70.4%) |

| Unknown | 18,407 (22.8%) | 62,415 (77.2%) | 3,388 (25.7%) | 9,777 (74.3%) |

| Hospital Region | ||||

| Northeast | 40,469 (27.6%) | 106,180 (72.4%) | 4,082 (21.6%) | 14,804 (78.4%) |

| Midwest | 30,937 (30.8%) | 69,655 (69.2%) | 5,741 (30.8%) | 12,919 (69.2%) |

| South | 104,200 (43.2%) | 137,127 (56.8%) | 16,481 (32.7%) | 33,992 (67.3%) |

| West | 31,230 (23.3%) | 102,942 (76.7%) | 4,036 (23.3%) | 13,306 (76.7%) |

| Hospital Teaching | ||||

| Non-teaching | 111,727 (35.0%) | 207, 418 (65.0%) | 16,476 (28.9%) | 40,460 (71.1%) |

| Teaching | 95,109 (31.3%) | 208,486 (68.7%) | 13,864 (28.6%) | 34,561 (71.4%) |

| GHTN/PEC/Eclampsia | 43,502 (36.6%) | 75,216 (63.4%) | 4,568 (28.3%) | 11,583 (71.7%) |

| History of VTE | 2,886 (87.6%) | 408 (12.4%) | 663 (69.9%) | 285 (30.1%) |

| Tobacco | 13,023 (34.9%) | 24,329 (65.1%) | 3,506 (36.4%) | 6,130 (63.6%) |

| Thrombophilia | 3,184 (84.3%) | 593 (15.7%) | 585 (77.8%) | 166 (22.1%) |

| SSD/thalassemia | 1,301 (44.5%) | 1,624 (55.5%) | 176 (53.8%) | 151 (46.2%) |

| Cardiac disease | 2,209 (42.9%) | 2,945 (57.1%) | 2,119 (57.4%) | 1,576 (42.6%) |

|

| ||||

| Antepartum factors | ||||

|

| ||||

| Infection | 5,413 (33.0%) | 11,003 (67.0%) | NA | NA |

| OHSS | 131 (71.2%) | 53 (28.8%) | NA | NA |

| Hyperemesis | 2,274 (20.1%) | 9,021 (79.9%) | NA | NA |

| Multiple gestation | 16,336 (38.1%) | 26,508 (61.9%) | NA | NA |

| Length of stay | ||||

| <7 days | 169,692 (32.1%) | 358,582 (67.9%) | NA | NA |

| ≥7 days | 37,144 (39.3%) | 57,322 (60.7%) | NA | NA |

|

| ||||

| Postpartum factors | ||||

|

| ||||

| PPH or transfusion | NA | NA | 3,989 (32.1%) | 8,425 (67.9%) |

| Puerperal infection | NA | NA | 2,616 (22.2%) | 9,154 (77.8%) |

| Other infections | NA | NA | 4,020 (50.8%) | 3,894 (49.2%) |

| Length of stay | ||||

| 1 day | NA | NA | 4,523 (18.6%) | 19,753 (81.4%) |

| 2 days | NA | NA | 7,451 (20.6%) | 28,781 (79.4%) |

| ≥3 days | NA | NA | 18,366 (41.0%) | 26,487 (59.0%) |

GHTN, gestational hypertension; PEC, preeclampsia; VTE, venous thromboembolism; SSD, sickle cell disease; OHSS, ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome; PPH, postpartum hemorrhage. NA, not applicable.

Table 2 demonstrates the adjusted model. Factors associated with increased use of antenatal venous thromboembolism prophylaxis included ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome (RR 2.01, 95% CI 1.69-2.39), history of venous thromboembolism (RR 2.08, 95% CI 2.01-2.17), thrombophilia (RR 1.99, 95% CI 1.92-2.07), and admission to a hospital in the South (RR 1.45, 95%CI 1.43-1.77, with the Northeast as a reference). Factors associated with decreased antepartum prophylaxis included hyperemesis (RR 0.56, 95% CI 0.54-0.59) and admission to a hospital in the West (RR 0.81, 95%CI 0.80-0.83 with the Northeast as a reference). Factors associated with increased use of postpartum venous thromboembolism prophylaxis included history of venous thromboembolism (RR 1.65, 95% CI 1.52-1.79), thrombophilia (RR 1.92, 95% CI 1.77-2.09), cardiac disease (RR 1.54, 95% CI1.47-1.61), hospital stay ≥3 days (RR 2.03, 95% CI 1.96-2.10), and admission to a hospital in the South (RR 1.43, 95%CI 1.38-1.48, with the Northeast as a reference). For the sensitivity analysis applying weights to the data to estimate the population prevalence for the entire United States, results were similar to the primary analysis. Prophylaxis for antepartum admissions increased from 19.4% in 2006 to 36.4% in 2015. Prophylaxis for postpartum readmissions increased from 21.9% to 31.4% over the same period.

Table 2. Adjusted models for antepartum and postpartum thromboprophylaxis.

| Antepartum | Postpartum | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Risk ratio | (95% confidence interval) | Risk ratio | (95% confidence interval) | |

| Year | ||||

| 2006 | 1.00 | (Reference) | 1.00 | Reference |

| 2007 | 1.28 | (1.24-1.31) | 1.09 | (1.03-1.16) |

| 2008 | 1.57 | (1.54-1.61) | 1.14 | (1.08-1.21) |

| 2009 | 1.81 | (1.77-1.85) | 1.24 | (1.18-1.31) |

| 2010 | 2.05 | (2.00-2.10) | 1.32 | (1.25-1.40) |

| 2011 | 2.12 | (2.08-2.18) | 1.36 | (1.29-1.43) |

| 2012 | 2.01 | (1.97-2.06) | 1.31 | (1.25-1.39) |

| 2013 | 1.93 | (1.89-1.97) | 1.34 | (1.27-1.41) |

| 2014 | 1.88 | (1.84-1.92) | 1.37 | (1.30-1.44) |

| 2015 (first quarter) | 1.94 | (1.88-2.01) | 1.31 | (1.21-1.43) |

| Hospital bed size | ||||

| <400 | 1.00 | Reference | 1.00 | Reference |

| 400-600 | 1.05 | (1.04-1.06) | 0.99 | (0.96-1.02) |

| >600 | 1.11 | (1.10-1.12) | 1.09 | (1.06-1.13) |

| Age | ||||

| 15-17 | 0.79 | (0.77-0.82) | 0.74 | (0.69-0.81) |

| 18-24 | 0.94 | (0.92-0.95) | 0.97 | (0.94-1.00) |

| 25-29 | 1.00 | Reference | 1.00 | Reference |

| 30-34 | 1.02 | (1.01-1.03) | 1.04 | (1.00-1.07) |

| 35-39 | 1.04 | (1.03-1.06) | 1.07 | (1.03-1.11) |

| ≥40 | 1.03 | (1.01-1.06) | 1.13 | (1.07-1.20) |

| Insurance status | ||||

| Medicare | 0.92 | (0.88-0.95) | 0.92 | (0.85-1.00) |

| Medicaid | 0.98 | (0.97-0.99) | 1.01 | (0.99-1.04) |

| Private | 1.00 | Reference | 1.00 | Reference |

| Other | 0.94 | (0.91-0.96) | 1.01 | (0.95-1.08) |

| Race | ||||

| White | 1.00 | Reference | 1.00 | Reference |

| Black | 0.95 | (0.94-0.96) | 1.06 | (1.03-1.09) |

| Hispanic | 0.87 | (0.85-0.89) | 1.03 | (0.98-1.09) |

| Other | 0.88 | (0.87-0.89) | 0.93 | (0.90-0.96) |

| Unknown | 1.07 | (0.90-1.27) | 0.58 | (0.31-1.08) |

| Urban Hospital Location | 1.26 | (1.23-1.28) | 0.99 | (0.93-1.03) |

| Single Marital Status | 1.02 | (1.01-1.03) | 1.00 | (0.97-1.03) |

| Hospital Region | ||||

| Northeast | 1.00 | Reference | 1.00 | Reference |

| Midwest | 1.1 | (1.08-1.11) | 1.44 | (1.38-1.50) |

| South | 1.45 | (1.43-1.47) | 1.43 | (1.38-1.48) |

| West | 0.81 | (0.80-0.83) | 1.14 | (1.09-1.20) |

| Teaching Hospital | 0.85 | (0.84-0.86) | 0.99 | (0.96-1.02) |

| GHTN/PEC/eclampsia | 1.04 | (1.03-1.05) | 0.98 | (0.95-1.01) |

| History of VTE | 2.08 | (2.01-2.17) | 1.65 | (1.52-1.79) |

| Thrombophilia | 1.99 | (1.92-2.07) | 1.92 | (1.77-2.09) |

| SSD/thalassemia | 1.21 | (1.14-1.27) | 1.35 | (1.16-1.57) |

| Cardiac disease | 1.22 | (1.17-1.27) | 1.54 | (1.47-1.61) |

| Tobacco | 1.13 | (1.10-1.17) | ||

|

| ||||

| Antepartum factors | ||||

|

| ||||

| Infection | 0.98 | (0.95-1.01) | NA | NA |

| OHSS | 2.01 | (1.69-2.39) | NA | NA |

| Hyperemesis | 0.56 | (0.54-0.59) | NA | NA |

| Multiple gestation | 1.09 | (1.08-1.11) | NA | NA |

| Length of stay | ||||

| <7 days | 1.00 | Reference | NA | NA |

| ≥7 days | 1.15 | (1.13-1.16) | NA | NA |

|

| ||||

| Postpartum factors | ||||

|

| ||||

| PPH or transfusion | NA | NA | 1.1 | (1.06-1.14) |

| Puerperal infection | NA | NA | 0.75 | (0.72-0.78) |

| Other infections | NA | NA | 1.53 | (1.48-1.58) |

| Length of stay | ||||

| 1 day | NA | NA | 1.00 | Reference |

| 2 days | NA | NA | 1.1 | (1.06-1.14) |

| ≥3 days | NA | NA | 2.03 | (1.96-2.10) |

GHTN, gestational hypertension; PEC, preeclampsia; VTE, venous thromboembolism; SSD, sickle cell disease; OHSS, ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome; PPH, postpartum hemorrhage. NA, not applicable. Risk ratios for medical and obstetrical risk factors are for presence of the condition with absence of the condition as the referent.

Discussion

This analysis demonstrated increased use of venous thromboembolism prophylaxis during the study period for both antepartum and postpartum hospitalizations. Prophylaxis during antepartum hospitalizations more than doubled between 2006 and 2015, while rates of postpartum prophylaxis increased by more than a third. While prophylaxis was most common for patients at highest risk for venous thromboembolism secondary to conditions such as ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome, a history of venous thromboembolism, or thrombophilia, increased prophylaxis was noted in the setting of other risk factors with lower attributable risk such as cardiac disease, sickle cell disease, and prolonged hospitalization. Of note, some diagnoses associated with increased venous thromboembolism risk (such as hyperemesis and postpartum endometritis) were associated with lower rates of prophylaxis.29 Variation in care, both on the regional and hospital level, played a significant role in prophylaxis; at some hospitals prophylaxis was common while at others it was rare. Prophylaxis rates were highest in the South and lowest in the Northeast and West. Many hospitals are routinely administering prophylaxis to patients with significant risk for venous thromboembolism while opportunities to reduce risk at other centers may be being missed.

The differential use of prophylaxis based on risk factors and across hospitals may be related to varying recommendations from major societies regarding venous thromboembolism prophylaxis. Recommendations from ACCP and the College are similar. ACCP defines high-risk hospitalized non-surgical patients as those with by a Padua score ≥4.9,10 The Padua score assigns risk based on the presence of risk factors such as age, cancer, the presence of a stroke or heart attack, and recent surgery. For such patients, who in pregnancy would primarily include women with reduced mobility, a history of venous thromboembolism, or known thrombophilia, prophylaxis is recommended. The College similarly supports anticoagulation for women “at significant risk of venous thromboembolism during pregnancy or the postpartum period, such as those with high risk acquired or inherited thrombophilias,”11 but is otherwise nonspecific. RCOG more clearly supports venous thromboembolism prophylaxis during non-delivery hospitalizations both in the most recent guideline released and in a prior iteration from 2009.29,30 This cohort included a selection of patients that based upon length of stay, comorbid diagnoses, or both is at increased risk for venous thromboembolism and would have prophylaxis supported by RCOG criteria.12 Patients hospitalized for >3 days antepartum3 or readmitted with a complication may be at particularly high risk for events.12

Our findings touch on important unanswered questions related to optimal obstetric venous thromboembolism prevention strategies. First, should venous thromboembolism prophylaxis during antenatal admissions and postpartum readmissions be risk-factor based or empiric? Prior research has demonstrated that many conditions associated with increased risk for venous thromboembolism will be common among antepartum admissions and postpartum readmissions. These include hypertensive diseases of pregnancy, multiple gestation, obesity, hyperemesis, infection, postpartum hemorrhage, and smoking.3,12 Given the prevalence of risk factors, that many women will have mobility reduced while hospitalized, that hospitalization appears to be risk factor in and of itself, and that in our analysis of at-risk patients with conditions such as postpartum endometritis and hyperemesis were actually less likely to receive prophylaxis, prophylaxis administered empirically and held on an “opt-out” basis in the setting of contraindications may represent a preferred strategy. This approach is supported by RCOG and the NPMS.12,13

A second important question is what is the optimal method of prophylaxis for hospitalized antepartum and postpartum patients? RCOG and NPMS support extensive pharmacologic prophylaxis with UFH or LMWH. However, other experts have advocated broader use of mechanical prophylaxis citing lower risk for complications and cost considerations with LMWH in particular.31 Further research is required to determine the relative costs, risks, and benefits of competing prophylaxis strategies. In particular, costs associated with LMWH versus UFH versus mechanical prophylaxis may differ based patient and hospital factors. Benefits of pharmacologic prophylaxis include that it can be predictably administered and that patient compliance is not a factor. Mechanical prophylaxis may be substandard if there is noncompliance from patients or if there is device malfunction. Risks of pharmacologic prophylaxis include complications during neuraxial anesthesia procedures, wound complications, and bleeding. Of note in our analysis a much larger proportion of postpartum patients receiving prophylaxis received pharmacologic management than antepartum patients, suggesting that providers may make decisions based on concerns related to neuraxial anesthesia and risk for wound complications. While determining which patients may most benefit from pharmacologic versus mechanical prophylaxis is outside the scope of our analysis, our study findings suggest that hospital-level prophylaxis strategies vary significantly; the heterogeneity of clinical approaches to venous thromboembolism prophylaxis for these patient populations currently in use may represent an opportunity to perform outcomes research to further clarify best practices.

There are several important limitations to be aware of in interpreting this study. First, given that prophylaxis was queried from billing data and not chart review or order entry, there is risk for under-ascertainment or misclassification of the outcome. However, prophylaxis use for the highest risk patients (those with ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome, prior venous thromboembolism, or thrombophilias) was much more likely for antepartum admissions or postpartum readmissions overall, suggesting that higher risk patients received prophylaxis based on clinical decision making and hospital policy and that high rates of prophylaxis were captured for these patients in our analysis. Additionally, prior analyses of high-risk, non-obstetric procedures by our group using the same data set demonstrated that higher use of venous thromboembolism prophylaxis could be captured using this methodological approach.20 A second important limitation of this study is that while we are able to estimate the number of patients who received prophylaxis, we were not able to examine the quality of prophylaxis. Compliance with mechanical prophylaxis among obstetric patients may be poor1 and we were not able to verify dosing, timing, and patient compliance with pharmacologic prophylaxis. Third, Perspective does not include data on outpatient medications or diagnoses and we were not able to (i) evaluate outpatient prophylaxis, or (ii) determine whether acute venous thromboembolism was present on admission or subsequently diagnosed during a hospitalization. A fourth limitation is that because many secondary diagnoses codes are not linked to reimbursement, some clinical risk factors may be underestimated. Direct BMI data is not available in Premier, and because of poor ascertainment obesity diagnoses were not included in this analysis. Fifth, Perspective does not have hospital-level data on electronic medical records systems and we were not able to evaluate how this factors was related to prophylaxis. Sixth, we did not evaluate postpartum complications that occurred during a delivery hospitalization and only evaluated postpartum readmissions. Seventh, we are not able to evaluate specific thrombophilias given that the diagnostic code is not specific. Eighth, because of limitations in linking hospitalizations for individual patients, we did not evaluate whether delivery occurred vaginally or by cesarean for postpartum readmissions.

In conclusion, findings from this analysis demonstrated increased overall use of venous thromboembolism prophylaxis during antepartum and postpartum non-delivery hospitalizations amid divergent and non-specific clinical guidelines. While use of venous thromboembolism prophylaxis may obviate some of the relatively high risk that obstetric patients face during postpartum and antepartum hospitalizations, best practices have not been clearly defined and further comparative effectiveness research is urgently need to optimize care in this setting. Many hospitals have determined that patients with significant risk for venous thromboembolism such as prolonged hospitalization and other factors should receive prophylaxis; with current practices opportunities to reduce risk may be being missed.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. Elena Kuklina at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention for her assistance in helping to identify the postpartum and antepartum cohorts.

Footnotes

Dr. Friedman is supported by a career development award (K08HD082287) from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, National Institutes of Health.

Presented as a poster at the 37th Annual Pregnancy Meeting for the Society for Maternal Fetal Medicine in Las Vegas, NV in January 23–28, 2017.

Financial Disclosure: The authors did not report any potential conflicts of interest.

Each author has indicated that he or she has met the journal's requirements for authorship.

References

- 1.Brady MA, Carroll AW, Cheang KI, Straight C, Chelmow D. Sequential compression device compliance in postoperative obstetrics and gynecology patients. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;125:19–25. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000000554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Creanga AA, Berg CJ, Syverson C, Seed K, Bruce FC, Callaghan WM. Pregnancy-related mortality in the United States, 2006-2010. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;125:5–12. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000000564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Abdul Sultan A, West J, Tata LJ, Fleming KM, Nelson-Piercy C, Grainge MJ. Risk of first venous thromboembolism in pregnant women in hospital: population based cohort study from England. Bmj. 2013;347:f6099. doi: 10.1136/bmj.f6099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Heit JA, Kobbervig CE, James AH, Petterson TM, Bailey KR, Melton LJ., 3rd Trends in the incidence of venous thromboembolism during pregnancy or postpartum: a 30-year population-based study. Annals of internal medicine. 2005;143:697–706. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-143-10-200511150-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Abdul Sultan A, Grainge MJ, West J, Fleming KM, Nelson-Piercy C, Tata LJ. Impact of risk factors on the timing of first postpartum venous thromboembolism: a population-based cohort study from England. Blood. 2014;124:2872–80. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-05-572834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ghaji N, Boulet SL, Tepper N, Hooper WC. Trends in venous thromboembolism among pregnancy-related hospitalizations, United States, 1994-2009. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2013;209:433. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2013.06.039. e1-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Callaghan WM, Creanga AA, Kuklina EV. Severe maternal morbidity among delivery and postpartum hospitalizations in the United States. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;120:1029–36. doi: 10.1097/aog.0b013e31826d60c5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Friedman AM, Ananth CV. Obstetrical venous thromboembolism: Epidemiology and strategies for prophylaxis. Semin Perinatol. 2016;40:81–6. doi: 10.1053/j.semperi.2015.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bates SM, Greer IA, Middeldorp S, et al. VTE, thrombophilia, antithrombotic therapy, and pregnancy: Antithrombotic Therapy and Prevention of Thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines. Chest. 2012;141:e691S–736S. doi: 10.1378/chest.11-2300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kahn SR, Lim W, Dunn AS, et al. Prevention of VTE in nonsurgical patients: Antithrombotic Therapy and Prevention of Thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines. Chest. 2012;141:e195S–226S. doi: 10.1378/chest.11-2296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.James A, Committee on Practice BO. Practice bulletin no. 123: thromboembolism in pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;118:718–29. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3182310c4c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.The Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. Thrombosis and Embolism during Pregnancy and the Puerperium, Reducing the Risk. Green-Top Guideline No 37a. 2015 [Google Scholar]

- 13.D'Alton ME, Friedman AM, Smiley RM, et al. National Partnership for Maternal Safety: Consensus Bundle on Venous Thromboembolism. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;128:688–98. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000001579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Friedman AM, Ananth CV, Lu YS, D'Alton ME, Wright JD. Underuse of postcesarean thromboembolism prophylaxis. Obstet Gynecol. 2013;122:1197–204. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000000007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Friedman AM, Ananth CV, Prendergast E, Chauhan SP, D'Alton ME, Wright JD. Thromboembolism incidence and prophylaxis during vaginal delivery hospitalizations. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015;212:221. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2014.09.017. e1-12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stulberg J, Delaney C, Neuhauser D, Aron D, Fu P, Koroukian S. Adherence to surgical care improvement project measures and the asssociation with postoperative infections. JAMA. 2010;303:2479–85. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fang M, Maselli J, Lurie J, Lindenauer P, Auerbach A. Use and outcomes of venous thromboembolism prophyalxis after spinal fusion surgery. J Thromb Haemost. 2011;9:1318–25. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2011.04326.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ritch J, Kim J, Lewin S, et al. Venous thromboembolism and use of prophylaxis among women undergoing laparoscopic hysterectomy. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;117:1367–74. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e31821bdd16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wright J, Lewin S, Shah M, et al. Quality of venous thromboembolism prophylaxis in patients undergoing oncologic surgery. Ann Surg. 2011;253:1140–6. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e31821287ac. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zacharia BE, Youngerman BE, Bruce SS, et al. Quality of Postoperative Venous Thromboembolism Prophylaxis in Neuro-oncologic Surgery. Neurosurgery. 2016 doi: 10.1227/NEU.0000000000001270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Prabhakaran S, Herbers P, Khoury J, et al. Is prophylactic anticoagulation for deep venous thrombosis common practice after intracerebral hemorrhage? Stroke. 2015;46:369–75. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.114.008006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kulik A, Rassen JA, Myers J, et al. Comparative effectiveness of preventative therapy for venous thromboembolism after coronary artery bypass graft surgery. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2012;5:590–6. doi: 10.1161/CIRCINTERVENTIONS.112.968313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jacobsen A, Skjeldestad F, Sandset P. Incidence and risk patterns of venouse thromboembolism in pregnancy and puerperium-a register-based case-control study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008;198:e1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2007.08.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sultan A, Tata L, West J, et al. Risk factors for first venous thromboembolism around pregnancy: a population-based cohort study from the United Kingdom. Blood. 2013;121:3953–391. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-11-469551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bates S, Greer I, Pabinger I, Sofaer S, Hirsh J, Physicians ACoC. Venous thromboembolism, thrombophilia, antithrombotic therapy, and pregnancy: American College of Chest Physicians evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. Chest. (8th) 2008;133(suppl):844S–86S. doi: 10.1378/chest.08-0761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.James A. Thromboembolism in prengnang: recurrence risks, prevention and management. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2008;20:550–6. doi: 10.1097/GCO.0b013e328317a427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lindqvist P, Torsson J, Almqvist A, Bjogell O. Postpartum thromboembolism: severe events might be preventable using a new risk score model. Vasc Health Risk Manag. 2008;4 doi: 10.2147/vhrm.s2831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Simpson E, Lawrenson R, Nightingale A, Farmer R. Venous thromboembolism in pregnancy and he puerperium: incidence and additional risk factors from a London perinatal database. BJOG. 2001;108:56–60. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2001.00004.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gynaecologists TRCoOa. Thrombosis and Embolism during Pregnancy and the Puerperium, Reducing the Risk. Green-Top Guideline No 37a. 2015 [Google Scholar]

- 30.The Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. Thrombosis and Embolism during Pregnancy and the Puerperium, Reducing the Risk. Green-Top Guideline No 37a. 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sibai BM, Rouse DJ. Pharmacologic Thromboprophylaxis in Obstetrics: Broader Use Demands Better Data. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;128:681–4. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000001656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]