Abstract

Background

A proportion of patients who sustain upper limb fractures develop post-traumatic stiffness (PTS), which may progress in a similar way to primary frozen shoulder (PFS). We have had success in treating PFS with manipulation under anaesthetic (MUA) and therefore treated PTS using MUA. Oxford Shoulder Scores (OSS), range of motion (ROM) data pre- and post-MUA, and the need for repeat procedure were compared.

Methods

Sixty-four patients with PTS following an upper limb fracture, unresponsive to conservative measures, were seen between 1 January 1999 and 1 November 2015. Thirty-two patients had sustained a proximal humeral fracture, six of whom had a concurrent shoulder dislocation. MUA was performed using a standard technique. The results were compared with 487 PFS patients undergoing the same procedure.

Results

There was no significant difference in ROM change between the groups. Improvement in OSS was slightly greater in the PFS group (17 versus 14, p = 0.005) but, upon subgroup analysis of the PTS group, no significant difference was found for patients presenting with humeral fractures alone.

Conclusions

MUA results for PTS following upper limb fracture are comparable to MUA for PFS. We therefore recommend MUA in PTS cases where conservative methods have failed.

Keywords: fracture, frozen shoulder, manipulation under anaesthetic, trauma

Introduction

Frozen shoulder (FS), or adhesive capsulitis, manifests as a gradual onset of pain in the shoulder, with a restriction of both active and passive movements, especially external rotation and elevation. This pattern of symptoms was described in 1934 by Codman,1 and, subsequently, its aetiology, pathology and management have been extensively investigated, although it still remains a relatively poorly understood condition. FS may be classified as primary (idiopathic) or secondary, with the latter being related to injury or other diagnosis (e.g. diabetes mellitus)2 and it can cause significant debilitation, such that not all cases progress to a spontaneous resolution.3

Fractures of the upper limb are common, with proximal humerus fractures accounting for 4% to 5% of all fractures,4 with an unknown but significant proportion of patients going on to develop post-traumatic stiffness (PTS). In the majority of cases, this may be managed with early mobilisation; however, some patients will develop an intractable stiffness, which may progress in a similar way to a primary FS (PFS). What is unknown is whether this PTS represents a similar pathology and natural history to PFS, or whether it is a completely different entity.

There is a consensus that FS follows a pattern consisting of three phases; the first, painful phase is otherwise known as the ‘freezing phase’. There is a gradual onset of insidious shoulder pain, with a concurrent decrease in range of motion (ROM). This is followed by a stiff or ‘frozen’ phase, during which active and passive ROM, especially in the external rotation and elevation planes, is lost. Pain may reduce during this stage. Finally, there is the resolution, or ‘thawing’ stage, where ROM gradually improves to normal, or near normal levels.5

Manipulation under anaesthetic (MUA) of PFS has been shown to provide good clinical outcomes,6,7 with a small number of complications.8 It is generally accepted as a reasonable management option. Our group has previously published results for MUA of FS in diabetics and for post-shoulder dislocation stiffness, which demonstrated similar functional outcomes compared to PFS patients.6,9 The present retrospective review of a large cohort of prospectively collected patients data outlines the association of PTS with various upper limb trauma fractures (excluding simple shoulder dislocations reported previously),9 as well as their outcomes, compared to PFS, following MUA.

Materials and Methods

Between 1 January 1999 and 1 November 2015, data on consecutive patients presenting with PTS following an upper limb fracture, or PFS, to a single surgeon (DAW) at a single centre were collected.

The patients all had plain radiographs of their shoulder confirming union of their fracture (if humerus or clavicle) and, in the case of the humeral fractures, no bony cause for their restriction was found. In the PFS cases, the radiographs were normal, excluding osteoarthritis as a cause for their restriction in range of motion. An identical protocol was followed for each patient by the surgeon (DAW); once the FS had been identified, and determined to be in the ‘frozen’ phase, MUA was advised. Patients were added to the next available operating list. Exclusion criteria included: (i) patients who were not fit for general anaesthetic and (ii) patients who declined MUA. The majority of these patients had previously been managed with a combination of oral analgesia, cortisone injections and variable length of physiotherapy, although they remained with a reduced range of motion of the shoulder and or pain, which was unacceptable to the patient.

The standard protocol for each patient was followed. Patients completed an Oxford Shoulder Score (OSS) prior to the procedure. A general anaesthetic was administered with the patient in a supine position. Pre-manipulation ROM was assessed and recorded. Internal rotation was assessed with the shoulder in neutral adducted position, the elbow flexed to 90° (with the patient supine, the wrist is vertically above the elbow; by internally rotating the shoulder, the angle of the forearm can be measured from the vertical).

MUA was then performed; holding the patient’s arm between the shoulder and elbow, the shoulder was initially moved into abduction, followed by flexion, external rotation, cross-body adduction and internal rotation. MUA was repeated until it was considered that the maximum ROM had been achieved, which was then documented. Next 10 mL of 0.5% bupivacaine and 80 mg of Depo-Medrone (Pharmacia Ltd, Sandwich, UK) was then injected anteriorly into the glenohumeral joint before general anaesthetic was ceased.

A standard postoperative physiotherapy regimen was offered to each patient, involving passive and active exercises, as well as hydrotherapy rehabilitation. Reassessment was then performed by the lead surgeon in an outpatient setting, at a mean of 24 days post-MUA, when OSS was recorded. If, at this stage, the patient was not satisfied with their ROM or pain levels, they were monitored for a variable period, as determined by the wishes of the patient. Those who did not have satisfactory relief of symptoms were offered a further MUA (mean interval of 17 weeks).

Statistical analysis was performed using Prism, version 6 (GraphPad, La Jolla, CA, USA). The data were first analysed for normality (D’Agostino-Pearson and Shapiro–Wilk tests) and, in the main, were found not to be normally distributed. A Mann–Whitney U-test was therefore used to analyse the data, apart from the few occasions when it was normally distributed, in which case a two-tailed t-test was used. p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Ethical approval was obtained from the medical advisory committee of the institution.

Results

In total, 67 patients with PTS following an upper limb fracture underwent MUA, two of whom were excluded as a result of loss to follow-up. One patient had undergone a shoulder hemiarthroplasty for fracture and, given that this changed the biology of the shoulder completely, this patient was also excluded, leaving 64 patients with complete data (Group A).

A total of 502 patients were identified as having PFS, of whom complete data were available for 487; this group therefore comprised the control group (Group B). The mean age was 51.7 years.

The mean age at first MUA in Group A was 50.8 years. Thirty-nine patients were female and 41 patients presented with left-sided symptoms. There were no bilateral cases. Four patients had diabetes mellitus, two of whom were insulin-dependent. Patients who had developed PTS received a manipulation no sooner than 6 months after their fracture, once radiological union had been confirmed and conservative measures to relieve the stiffness had been attempted.

Table 1 outlines the upper limb trauma index injury for patients in Group A. Of the 64 patients, 11 underwent a surgical intervention as part of their fracture management. Surgical fixation comprised of either open reduction with internal fixation (ORIF), or intramedullary fixation.

Table 1.

Aetiology of upper limb fractures in patients presenting with post-traumatic stiffness (PTS), and those who underwent surgical fixation.

| Proportion of patients presenting with PTS following shoulder trauma | ||

|---|---|---|

| Total | Operative management | |

| Great tuberosity fracture | 15 | 3 |

| Proximal humerus fracture | 12 | 4 |

| Clavicle fracture | 10 | – |

| Shoulder fracture-dislocation | 6 | 1 |

| Wrist fracture | 4 | 1 |

| Midshaft humerus fracture | 2 | 2 |

| Greater tuberosity ‘bone bruise’ (identified on MRI) | 2 | – |

| Distal humerus fracture | 1 | – |

| Elbow dislocation | 1 | – |

| Scaphoid fracture | 1 | – |

| Total | 64 | 11 |

MRI, magnetic resonance imaging.

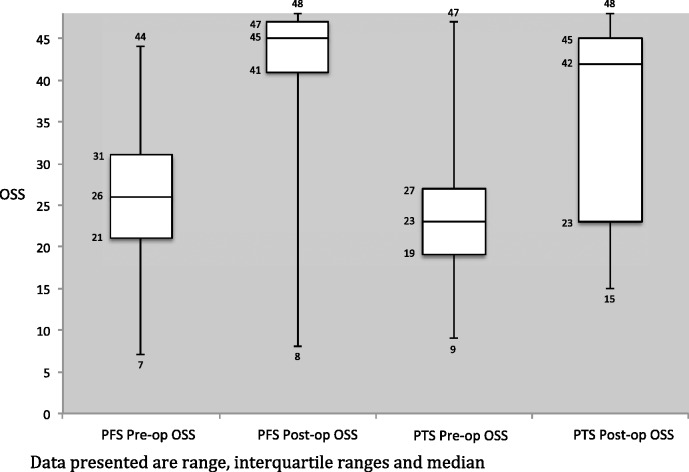

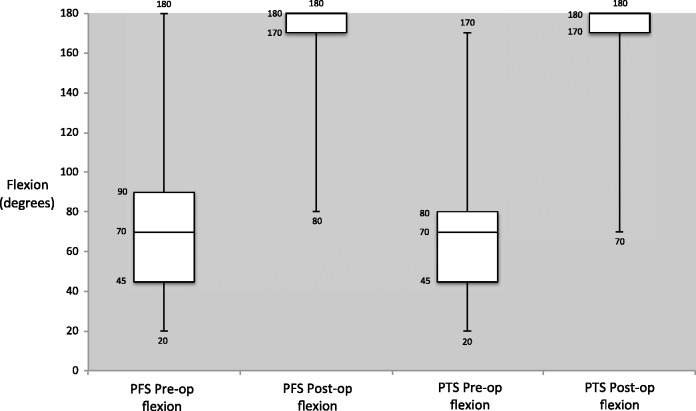

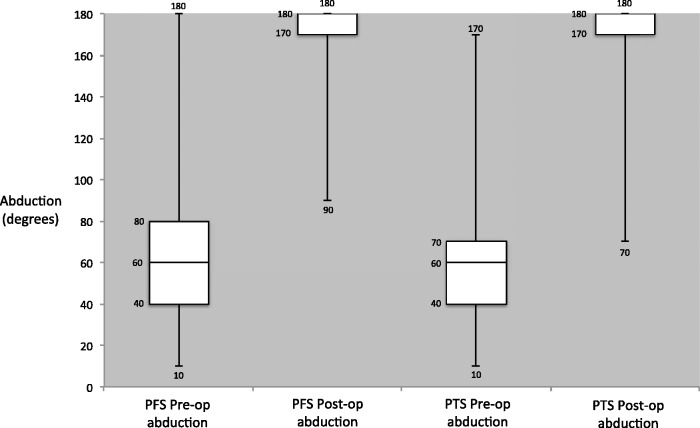

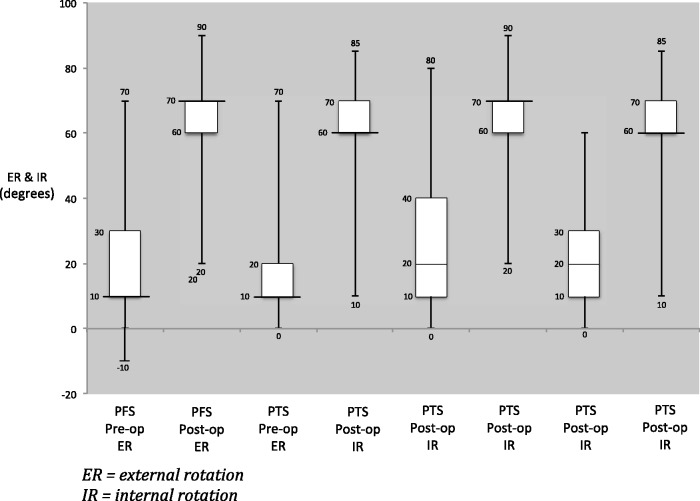

For the ROM results, there was no significant difference in the pre- and post-MUA ROM between the two groups. The only exception was post-MUA internal rotation, where the difference represents less than 10°, which may not be clinically significant (Table 2). Significant differences (p < 0.001) in OSS were observed for both the PTS and PFS groups pre- and post-MUA, which was encouraging. Comparing the PTS and PFS groups, the change in OSS was significantly higher in the PFS group (Group B) (17 versus 14, p = 0.005), with the PFS group (Group B) achieving a mean OSS of 43 post-MUA, compared to 39 in the PTS group (Group A). Change in OSS and ROM pre- and post-MUA are shown graphically in figures 1–4.

Table 2.

Oxford Shoulder Score and range of motion data.

| Variable | PTS Group A | PFS Group B | p-value A versus B |

|---|---|---|---|

| OSS before first MUA | 25 (9 to 47) | 26 (7 to 44) | 0.17 |

| OSS after first MUA | 39 (15 to 48) | 43 (8 to 48) | 0.002* |

| Pre- versus Post-MUA significance | P < 0.001* | P < 0.001* | |

| Change in OSS | 14 (–7 to 31) | 17 (–8 to 40) | 0.005* |

| ROM | |||

| Before first MUA | |||

| Flexion | 70° (20° to 170°) | 70° (20° to 180°) | 0.8 |

| Abduction | 60° (10° to 170°) | 60° (10° to 180°) | 0.9 |

| External rotation | 20° (0° to 70°) | 20° (–10° to 70°) | 0.7 |

| Internal rotation | 20° (0° to 60°) | 30° (0° to 80°) | 0.4 |

| After first MUA | |||

| Flexion | 170° (70° to 180°) | 170° (80° to 180°) | 0.7 |

| Abduction | 170° (70° to 180°) | 170° (90° to 180°) | 0.8 |

| External rotation | 60° (10° to 85°) | 70° (20° to 90°) | 0.1 |

| Internal rotation | 60° (10° to 85°) | 70° (20° to 90°) | 0.03* |

PTS, post-traumatic stiffness; PFS, primary frozen shoulder; OSS, Oxford Shoulder Score; ROM, range of motion; MUA, manipulation under anaesthetic; Data are presented as the mean (range).

Figure 1.

Pre- and post-manipulation under anaesthetic Oxford Shoulder scores (OSS) for primary frozen shoulder (PFS) and post-traumatic stiffness (PTS).

Figure 2.

Pre- and post-manipulation under anaesthetic flexion range of motion in primary frozen shoulder (PFS) and post-traumatic stiffness (PTS).

Figure 3.

Pre- and post-manipulation under anaesthetic abduction range of motion in primary frozen shoulder (PFS) and post-traumatic stiffness (PTS).

Figure 4.

Pre- and post-manipulation under anaesthetic external rotation (ER) and internal rotation (IR) in primary frozen shoulder (PFS) and post-traumatic stiffness (PTS).

Some patients went on to require a repeat MUA. In the PTS group, this comprised 11/64 (17.2%) and, in the PFS group (Group B), 98/487 patients required repeat MUA (20%). Of the 12 patients who had undergone operative management for their fracture, one patient received a repeat MUA (8.3%). There was no significant difference in either the OSS data or the ROM results when comparing the groups for repeat MUA (Table 3).

Table 3.

Oxford Shoulder Score and range of movement data for patients undergoing repeat MUA.

| PTS Group A | PFS Group B | p-value A versus B | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number | 11 | 98 | |

| OSS before second MUA | 27 (15 to 42) | 29 (8 to 45) | 0.5 |

| OSS after second MUA | 40 (27 to 48) | 42 (17 to 48) | 0.2 |

| Pre- versus Post-MUA significance | p < 0.001* | p < 0.001* | |

| Difference in OSS | 11 (3 to 27) | 12 (2 to 35) | 0.9 |

| ROM before second MUA | |||

| Flexion | 100° (60° to 170°) | 110° (30° to 70°) | 0.6 |

| Abduction | 100° (50° to 170°) | 100° (10° to 70°) | 0.7 |

| External rotation | 40° (10° to 60°) | 40° (–10° to 80°) | 0.6 |

| Internal rotation | 40° (10° to 60°) | 40° (0° to 80°) | 0.7 |

| ROM after second MUA | |||

| Flexion | 170° (160° to 180°) | 170° (120° to 180°) | 0.4 |

| Abduction | 170° (150° to 180°) | 170° (120° to 180°) | 0.5 |

| External rotation | 60° (50° to 70°) | 60° (40° to 80°) | 0.7 |

| Internal rotation | 70° (60° to 70°) | 60° (45° to 80°) | 0.3 |

PTS, post-traumatic stiffness; PFS, primary frozen shoulder; OSS, Oxford Shoulder Score; ROM, range of motion; MUA, manipulation under anaesthetic; Data are presented as the mean (range).

Subgroup analysis was performed for those patients who received a surgical intervention. No significant difference was observed in OSS or ROM data when comparing those who had undergone surgery with those who received non-operative management.

Discussion

Previous series have outlined the complication of FS following surgery for proximal humerus fractures. In 2010, Clavert et al.10 found that 4.1% (three of 73 patients) who had undergone ORIF for fractured proximal humerus developed PTS. Their patients were managed using an arthroscopic release; however, further follow-up was not reported.

Horneff and Namdari,11 in their instructional article on postoperative shoulder stiffness, emphasise the importance of distinguishing postoperative stiffness as a result of a bony or anatomical cause from that of FS. They advocate the use of arthroscopic capsular release rather than MUA because of concerns over refracture, and release was performed at 6 months to 9 months following ORIF. Horneff and Namdari11 did not report any clinical results with which we could compare our outcomes.

Although shoulder stiffness following upper limb fracture is a well-recognised complication, the incidence of PTS is unknown. Reviewing the literature provides little in the way of prevalence and management of these patients. The only similar study by Wang et al.12 compared the results of short- and long-term outcomes following FS MUA for idiopathic (primary), postoperative and post-injury FS. Wang et al.12 utilised the Constant Shoulder Score, investigating 47 patients (51 shoulders). In all three of their groups, there was a significant improvement in the Constant Shoulder Score, from a pre-operative median of 22.8 to 52.6 postoperatively. This score was generally maintained for the longer-term follow-up of 82 months. The postsurgery group did produce lower scores in terms of pain and ROM data compared to the primary FS and post-trauma groups, although the total Constant Shoulder Score was still comparable to the other two groups.

The pathological findings of FS tissue have demonstrated chronic inflammatory changes, with active fibroblastic proliferation.13,14 Increased nerve and vascular tissue is also a feature13 and primary FS is often characterised as contracture of the glenohumeral capsule, the coracohumeral ligament and subscapularis, as well as as excessive type III collagen secretion, resulting in contracture of the subacromial bursa.14 The pathology of PTS is poorly understood, although it is considered that increased contraction of the rotator cuff is the main cause. This theory was supported by Levy et al.15 who performed arthroscopic capsular release on 21 patients presenting with post-traumatic shoulder stiffness. They described soft tissue adhesions and contracture as the overwhelming operative findings.

We did not encounter any significant complications in this group, other than the need for repeat MUA in a small proportion of patients. However, it is accepted that fracture may be a complication of MUA.8 We therefore would not advocate the use of MUA in patients who clearly have osteoporosis, or evidence of an un-united fracture.

We acknowledge the limitations of this retrospective single surgeon cohort study. There will be some patients who were not included because, instead, they would have been discharged from a fracture clinic, regardless of whether they were fit or unwilling to undergo MUA. Some patients will not have re-presented, accepting that a post-injury decreased ROM may be ‘part and parcel’ of having sustained a fracture, and that this would be a normal post-injury course. The incidence of PTS following trauma is therefore likely to be higher than in this series. Furthermore, we appreciate that the significant differences that were observed were related to OSS, rather than objective change in ROM; an improvement in OSS could be attributed to possible placebo effect; however, we feel the OSS reflects genuine improvement in subjective symptoms in these patients.

The mean age of patients at first MUA was 50.8 years. Comparatively, this may be considered to be much younger than the usual population in whom a proximal humeral fracture is seen. This is therefore a young patient cohort, although it does include fractures with a younger age of presentation (e.g. clavicle fractures). We have not included rotator cuff injuries in this group, choosing instead to focus on bony trauma, although this group also has an incidence of PTS.

Despite our short follow-up time, we have previously presented work showing that OSS is maintained in the longer term for patients following MUA.7,16

We have also shown that patients usually respond to MUA within a very short time frame, usually within a few days, and certainly within 3 weeks, such that, if no or minimal improvement is shown at follow-up, then further progress is unlikely. However, we attempt further non-operative treatment in these patients unless (or until) they make no further progress and therefore the offer of a repeat MUA at this stage is justified.

Conclusions

The present study has shown that MUA does give measurable improvement for patients presenting with PTS that has failed other non-operative measures. The ROM data demonstrated no significant difference between the PTS and PFS groups, although the change in OSS did appear to be significantly higher (17 versus 14) in the PFS group. It is unclear whether PTS represents a different pathological aetiology from PFS, although certainly MUA appears to be an acceptable management option with good functional results and we have experienced no complications using this method.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. The paper has not been presented at any society or meeting.

Funding

The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Ethical Review and Patient Consent

The study did not undergo institutional review board approval because it is considered as a service evaluation assessment.

References

- 1.Codman EA. The shoulder: ruptures of the supraspinatus tendon and other lesions in or about the subacromial bursa, Boston, MA: Thomas Todd and Company, 1934. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Robinson CM, Seah KTM, Chee YH, et al. Frozen shoulder. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2012; 94B: 1–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hand C, Clipsham K, Ress J, et al. Long-term outcome of frozen shoulder. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2008; 17: 231–236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bell J, Leung B, Spratt K, et al. Trends and variation in incidence, surgical treatment and repeat surgery of proximal humerus fractures in the elderly. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2011; 93: 121–131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Reeves B. The natural history of the frozen shoulder syndrome (abstract only). Scand J Rheum 1975; 4: 193–196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jenkins EF, Thomas W, Corcoran J, et al. The outcome of manipulation under general anaesthesia for the management of frozen shoulder in patients with diabetes mellitus. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2012; 21: 1492–1498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Thomas W, Jenkins E, Owen J, et al. Treatment of frozen shoulder by manipulation under anaesthetic and injection: does the timing of treatment affect the outcome? J Bone Joint Surg Br 2011; 93B: 1377–1381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Loew M, Heichel T, Lehner B. Intraarticular lesions in primary frozen shoulder after manipulation under general anaesthesia. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2005; 14: 16–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nagata H, Thomas W, Woods DA. The management of secondary frozen shoulder after anterior shoulder dislocation – the results of manipulation under anaesthesia and injection. J Orthop 2015; 13: 100–105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Clavert P, Adam P, Bevort A, et al. Pitfalls and complications with locking plate for proximal humerus fracture. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2010; 194: 489–494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Horneff JG, Namdari S. My shoulder is stuck. Limited range of motion after open reduction and internal fixation of the shoulder. Curr Orthop Pract 2014; 253: 227–232. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang J, Huang T, Hung S, et al. Comparison of idiopathic, post-trauma and post-surgery frozen shoulder after manipulation under anaesthesia. Int Orthop 2007; 31: 333–337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bunker T, Anthony P. The pathology of frozen shoulder: a Dupuytren-like disease. J Bone Joint Surg Br 1995; 77B: 677–683. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hand GCR, Athanasou NA, Matthews T, et al. The pathology of frozen shoulder. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2007; 89B: 928–932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Levy O, Webb M, Even T, et al. Arthroscopic capsular release for posttraumatic shoulder stiffness. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2008; 17: 410–414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Theodorides A, Owen J, Sayers A, et al. Factors affecting short- and long-term outcomes of manipulation under anaesthesia in patients with adhesive capsulitis of the shoulder. Shoulder Elbow 2014; 6: 245–256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]