ABSTRACT

To investigate the prognostic value of tumor infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs: CD8+ and FoxP3+), and PD-L1 expression in patients with head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC) treated with radiotherapy combined with cisplatin (CRT) or cetuximab (BRT). Immunohistochemistry for CD8, FoxP3 was performed on pretreatment tissue samples of 77 HNSCC patients. PD-L1 results were evaluable in 38 patients. Cox regression analysis was used to analyze the correlations of these biomarkers expression with clinicopathological characteristics and treatment outcomes. High CD8+ TILs level was identified in multivariate analysis (MVA) as an independent prognostic factor for improved progression-free survival with a non-significant trend for better overall survival (OS). High FoxP3+ TILs and PD-L1+ correlated with a favorable OS in the uni-variate analysis, respectively, but not in the MVA. In subgroup analysis, CD8+TILs appear to play a pivotal role, p16+/high CD8+TILs patients had superior 5-year OS compared with p16+/low CD8+TILs, p16-/ high CD8+TILs, and p16-/ low CD8+TILs patients. p16+/PD-L1+ patients had improved 3-year OS compared with p16+/PD-L1-, p16-/ PD-L1+, and p16-/ PD-L1- patients. In low CD8+ TILs tumors, 5-year loco-regional control of patients treated with CRT was improved vs. those with BRT (p = 0.01) while no significant difference in high CD8+ TILs was observed. CD8+ TILs correlated with an improved clinical outcome in HNSCC patients independent of Human papillomavirus status. The immunobiomarkers may provide information for selecting suitable patients for cisplatin or cetuximab treatment. Additionally, the impact of TILs and PD-L1 of deciphering among the p16+ population a very favorable outcome population could be of interest for patients tailored approaches.

KEYWORDS: Biomarker, CD8, head and neck squamous cell carcinoma, human papillomavirus, PD-L1, tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes

Introduction

New biomarkers have considerably modified cancer patient management in the past years. Human papillomavirus (HPV)-positive head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC) is considered a distinct tumor entity, in terms of its molecular biology, carcinogenesis, and prognosis.1 The exact explanation for this is not fully clarified and seems to be multifactorial including different radio/chemo-sensitivity and genetic heterogeneity.2 Recent years it has been increasingly recognized that the immune system plays an important role in carcinogenesis and tumor progression. Various cells of the immune system provide a complex network of defense, with effective communication via cytokines.3 A better understanding of the dynamics of immune biomarker expression, as well as a detailed assessment of their expression patterns will be an important step to improve therapeutic efficacy and minimize treatment side effects.

Cytotoxic CD8+ tumor infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) are thought to be the major effector immune cells directed against tumor cells. Emerging evidence suggests that a high density of CD8+ T cells predicts favorable outcomes in several malignancies.4-7 There's also existing evidence which suggests that regulatory T cells (Tregs) that express the forkhead box P3 (FoxP3) transcription factor have the ability to inhibit host immune response via suppression of antitumor cytotoxic T cells. Some previous studies have suggested that higher FoxP3 Treg infiltrates were associated with a poor prognosis in a variety of malignancies including breast, lung, cervical and ovarian cancers, while in others their presence was associated with better prognosis, such as colorectal cancer.8 So far the results are still conflicting.

In recent years, one of the most promising therapeutic strategies involves blocking programmed death-1 (PD-1) or programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) to increase tumor susceptibility to antitumor T cells. In the CheckMate-141 trial, the anti–PD-1 monoclonal antibody nivolumab resulted in longer overall survival (OS) than standard chemotherapy in patients with recurrent HNSCC.9 More recently, the immunomodulatory effects of radiotherapy have been reported in both preclinical and clinical studies. Thus, it is important to understand the relationships between TIL distribution, PD-L1 expression and patient prognosis in HNSCC patients treated with chemo-/bio-radiotherapy.

In the current study, we investigated CD8, FoxP3 and PD-L1 expression to assess the prognostic value of the 3 markers, as well as their potential predictive values and correlation between these biomarkers and clinicopathological factors in a series of patients with HNSCC treated with concurrent chemoradiotherapy (CRT) with cisplatin or bioradiotherapy (BRT) with cetuximab.

Results

Patient characteristics

Enrolled patients were treated between June 2006 and October 2012. The clinical and pathological characteristics of the patients included in this study are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Baseline patient characteristics (N = 77)

| CD8 (*102/mm2) |

FoxP3 (*102/mm2) |

PD-L1 (1%)(N = 38) |

PD-L1 (5%) (N = 38) |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics | N (%) | Mean(SD) | p | Mean (SD) | p | − | + | p | − | + | p |

| Age (years) | 0.84 | 0.71 | 1.0 | 0.45 | |||||||

| <65 | 60 (78) | 3.5 (4.1) | 3.0 (2.7) | 8 (28) | 21 (72) | 13 (45) | 16 (55) | ||||

| > = 65 | 17 (22) | 4.3 (5.6) | 3.7 (4.0) | 3 (33) | 6 (67) | 6 (67) | 3 (33) | ||||

| Gender | 0.73 | 0.73 | 0.40 | 1.0 | |||||||

| Male | 61 (79) | 3.6 (4.7) | 3.2 (3.1) | 7 (24) | 22 (76) | 14 (48) | 15 (52) | ||||

| Female | 16 (21) | 3.7 (3.8) | 3.1 (2.9) | 4 (44) | 5 (56) | 5 (56) | 4 (44) | ||||

| Smoking status | 0.17 | 0.36 | 0.43 | 0.46 | |||||||

| Never/Former | 50 (65) | 3.9 (4.4) | 3.2 (2.8) | 7(25) | 21 (75) | 13 (46) | 15 (54) | ||||

| Current | 27 (35) | 3.1 (4.7) | 3.1 (3.4) | 4 (40) | 6 (60) | 6 (60) | 4 (40) | ||||

| PS (ECOG) | 0.43 | 0.46 | 0.69 | 1.0 | |||||||

| 0 | 55 (71) | 4.1 (5.0) | 3.4 (3.4) | 9 (32) | 19 (68) | 14 (50) | 14 (50) | ||||

| ≥ 1 | 22 (29) | 2.6 (2.6) | 2.4 (1.7) | 2 (20) | 8 (80) | 5 (50) | 5 (50) | ||||

| Charlson index | 0.75 | 0.47 | 0.29 | 0.02 | |||||||

| 0–1 | 50 (65) | 3.8 (4.5) | 3.2 (2.9) | 5 (22) | 18 (78) | 8 (35) | 15 (65) | ||||

| ≥ 2 | 27 (35) | 3.4 (4.6) | 3.0 (3.3) | 6 (40) | 9 (60) | 11 (73) | 4 (27) | ||||

| Location | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.71 | 0.49 | |||||||

| Oropharynx | 51 (66) | 4.4 (5.1) | 3.7 (3.5) | 7 (27) | 19 (73) | 14 (54) | 12 (46) | ||||

| Non-oropharynx | 26 (34) | 2.1 (2.5) | 2.0 (1.2) | 4 (33) | 8 (67) | 5 (42) | 7 (58) | ||||

| T classification | 0.03 | 0.03 | 1.0 | 1.0 | |||||||

| T1–3 | 58 (75) | 4.1 (4.8) | 3.6 (3.3) | 9 (29) | 22 (71) | 16 (52) | 15 (48) | ||||

| T4 | 19 (25) | 2.1 (2.7) | 1.9 (1.2) | 2 (29) | 5 (71) | 3 (43) | 4 (57) | ||||

| N classification | 0.001 | 0.04 | 0.17 | 0.02 | |||||||

| N0–1 | 40 (52) | 2.1 (2.4) | 2.3 (1.6) | 7 (41) | 10 (59) | 12 (71) | 5 (29) | ||||

| N2–3 | 37 (48) | 5.3 (5.6) | 4.1 (3.8) | 4 (19) | 17 (81) | 7 (33) | 14 (67) | ||||

| Overall stage | 0.19 | 0.36 | 0.46 | 0.09 | |||||||

| III | 29 (38) | 2.5 (2.7) | 2.4 (1.7) | 5 (39) | 8 (62) | 9 (69) | 4 (31) | ||||

| IV | 48 (62) | 4.3 (5.2) | 3.6 (3.5) | 6 (24) | 19 (76) | 10 (40) | 15 (60) | ||||

| HPV/p16 status | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.15 | 0.74 | |||||||

| p16+ | 21 (27) | 7.3 (6.2) | 5.9 (4.3) | 2 (13) | 13 (87) | 7 (47) | 8 (53) | ||||

| P16- | 56 (73) | 2.3 (2.6) | 2.1 (1.3) | 9 (39) | 14(61) | 12 (52) | 11 (48) | ||||

| Concurrent regimen | 0.01 | 0.22 | 0.07 | 0.1 | |||||||

| CRT | 45 (58) | 4.4 (4.8) | 3.4 (3.2) | 4 (17) | 19 (83) | 9 (39) | 14 (61) | ||||

| BRT | 32 (42) | 2.6 (3.9) | 2.8 (2.8) | 7 (47) | 8 (53) | 10 (67) | 5 (33) | ||||

| PD-L1 (1%)1 | 0.22 | 0.76 | — | — | |||||||

| Negative | 10 (32) | 2.0 (1.6) | 3.4 (2.4) | — | — | — | — | ||||

| Positive | 21 (68) | 4.5 (5.9) | 4.2 (3.9) | — | — | — | — | ||||

| PD-L1 (5%)1 | 0.54 | 0.23 | — | ||||||||

| Negative | 17 (55) | 3.1 (4.5) | 3.4 (3.2) | — | — | — | — | ||||

| Positive | 14 (45) | 4.4 (5.7) | 4.6 (3.8) | — | — | — | — | ||||

CRT: chemoradiotherapy with concurrent cisplatin; BRT: bioradiotherapy with concurrent cetuximab; PS: performance status; ECOG: Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group

One N = 31

Survival and relapse

The median follow-up time was 51.3 months (range 3.7–103.9 months). The 5-year actuarial OS, progression-free survival (PFS), loco-regional control (LRC) and distant control (DC) for the entire population were 53.7%, 44.7%, 72.7% and 73.4%, respectively.

Biomarkers expression

The number of CD8+ T cells ranged from 27 to 2216/mm2 with a median of 197.5/mm2. The number of FoxP3+ T cells ranged from 23 to 1516/mm2 with a median of 235/mm2. Given the absence of widely-accepted standard cut-off points for CD8 and FoxP3 expression that define clinical outcomes, median density of positive cells were used to define low expression (<median) and high expression (≥median). Of the 38 patients whose biopsy were from formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded specimens and were evaluable, using the cutoff level of 1%, PD-L1 expression was positive in 27 (71.1%) patients and negative in 11 (28.9%) patients; using the cutoff level of 5%, PD-L1 expression was positive in 19 (50.0%) patients and negative in 19 (50%) patients

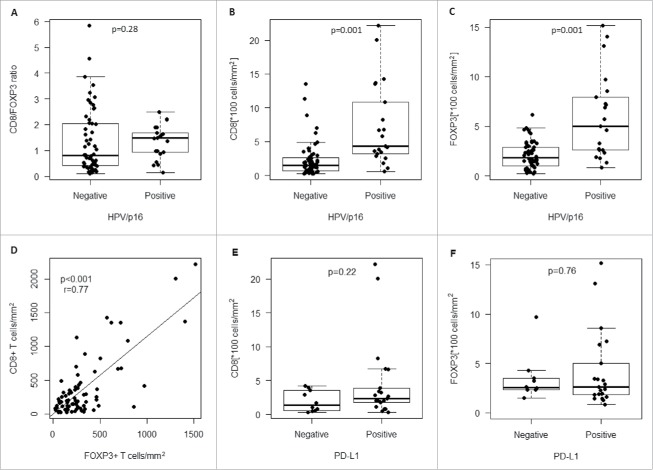

The median value of the CD8/FoxP3 ratio was 0.97 (range, 0.1–5.85) in the whole population, 1.09 (range, 0.13–2.5) in HPV/p16 positive patients and 0.97 (range, 0.1–5.85) in HPV/p16 negative patients. The CD8/FoxP3 ratios were not significantly different between the 2 subgroups of patients (p = 0.28) (Fig. 1A).

Figure 1.

A) CD8/FOXP3 infiltration ratio according to HPV/p16 status; Distribution of B) CD8+ infiltrating lymphocytes and C) FOXP3+ T regulatory infiltrating lymphocytes according to HPV/p16 status; D) Correlation of density of FOXP3+ T regulatory infiltrating lymphocytes and CD8+ infiltrating lymphocytes numbers (r = 0.77, p = 0.006); Distribution of E) CD8+ infiltrating lymphocytes and F) FOXP3+ T regulatory infiltrating lymphocytes according to PD-L1 status (1% cutoff level).

Association among pretreatment variables

Regarding the correlation of the immune markers with the clinicopathologic characteristics, CD8+ and FoxP3+ TIL densities differed significantly by primary tumor location, T stage, N stage and HPV/p16 status (Table 1). PD-L1 expression (1%+) didn't correlated with other clinicopathologic factors; PD-L1 expression (5%+) differed significantly by Charlson index and N stage. PD-L1 expression (1%+ or 5%+) was not significantly different between HPV/p16+ and HPV/p16- patients (p = 0.15, p = 0.74, respectively, Table 1). As shown in Fig. 1B, C, densities of CD8+ and FoxP3+ infiltrates were higher in HPV/p16+ tumors compared with HPV/p16− tumors (p = 0.001, p = 0.001, respectively). No other significant relationship between immune markers expression and clinicopathologic parameters were observed (Table 1).

Pearson correlation analysis showed that there was a strong significant correlation between CD8+ and FoxP3+ expression (r = 0.77, p < 0.001). Patients with high CD8+ TILs were also more likely to have high FoxP3 TILs (Fig. 1D). Densities of CD8+ and FoxP3+ infiltrates were not significantly different between PD-L1+ and PD-L1− patients (1%, p = 0.22, p = 0.76; 5%, p = 0.54, p = 0.23, respectively) (Fig. 1E, F, Fig. S1A, S1B).

Correlation with prognosis

Univariate analyses (UVA) were performed to evaluate factors potentially associated with OS and PFS. As shown in Table 2, the clinicopathological parameters including T stage, p16 status, CD8 expression and FoxP3 expression correlated with OS, whereas T stage, PS, Charlson index, p16 status, CD8 expression and FoxP3 expression correlated with PFS.

Table 2.

Univariate analyses of overall survival (OS) and progression-free survival (PFS) of the entire population (N = 77).

| OS |

PFS | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| UVA |

MVA | UVA |

MVA | |||||

| Characteristics | HR | P | HR (95% CI) | P | HR | P | HR(95%CI) | P |

| T4 classification (T1–3) | 3.9 | <0.001 | 4.0 (1.8–9.0) | 0.001 | 3.6 | <0.001 | 4.5 (2.1–9.7) | <0.001 |

| N2–3 classification (N0–1) | 1.1 | 0.72 | 2.4 (1.0–5.8) | 0.048 | 1.2 | 0.48 | 2.4 (1.1–5.3) | 0.03 |

| Never/Former smoker | 0.9 | 0.70 | 0.5 (0.2–1.1) | 0.09 | 0.8 | 0.47 | 0.41 (0.2–0.9) | 0.02 |

| (Current) | ||||||||

| BRT (CRT) | 1.2 | 0.56 | — | — | 1.3 | 0.48 | — | — |

| PS = 0 (PS≥ 1) | 0.6 | 0.12 | 0.8 (0.4–1.7) | 0.54 | 0.5 | 0.03 | 0.9 (0.4–1.9) | 0.79 |

| Charlson index≥ 2 (0–1) | 1.7 | 0.12 | 1.6 (0.7–3.3) | 0.23 | 2.0 | 0.02 | 2.7 (1.3–5.6) | 0.01 |

| Age≥ 65 y (< 65) | 1.2 | 0.73 | — | — | 1.1 | 0.74 | — | — |

| Male (Female) | 0.9 | 0.82 | — | — | 1.1 | 0.90 | — | — |

| p16+(p16-) | 0.1 | 0.003 | 0.1 (0.02–0.6) | 0.01 | 0.3 | 0.01 | 0.3 (0.1–0.97) | 0.04 |

| CD8 | 0.4 | 0.02 | 0.4 (0.2–1.1) | 0.07 | 0.4 | 0.01 | 0.3 (0.1–0.7) | 0.01 |

| FoxP3 | 0.4 | 0.01 | 1.2 (0.4–3.8) | 0.79 | 0.5 | 0.04 | 1.6 (0.5–4.9) | 0.38 |

| CD8/FOXP3 | 1.1 | 0.35 | — | — | 1.1 | 0.40 | — | — |

CRT: chemoradiotherapy with concurrent cisplatin; BRT: bioradiotherapy with concurrent cetuximab; PS: performance status; ECOG: Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group

Intensities of CD8 and FOXP3 expression were on a log10 scale.

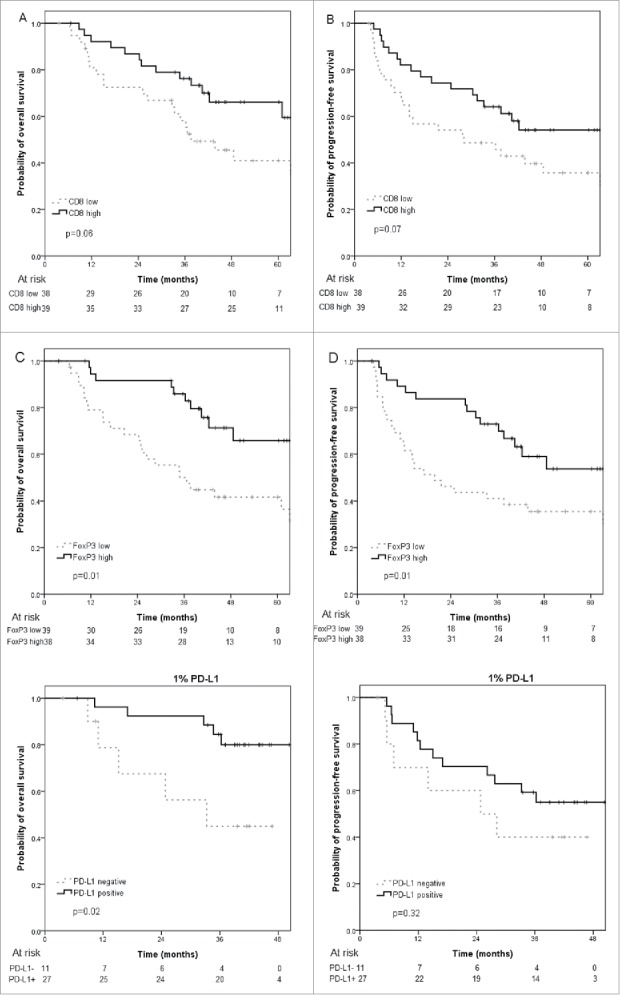

Multivariate analysis (MVA) for OS and PFS included T classification, N classification, smoking status, HPV/p16 status, Charlson index and CD8 and FoxP3 expression. Besides T stage, N stage, and HPV/p16 status, CD8+ TILs was a significant independent favorable prognostic factor for PFS (HR = 0.3, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.1–0.7, p = 0.01) and there was a non-significant trend for better OS (HR = 0.4, 95%CI 0.2–1.1, p = 0.07) (Table 2). Five-year OS was 66.1% for patients with high CD8+ infiltrates vs. 40.9% for those with low CD8+ infiltrates (p = 0.06) (Fig. 2A); Five-year PFS was 54.1% for patients with high CD8+ infiltrates vs. 35.7% for those with low CD8+ infiltrates (p = 0.07) (Fig. 2B). Meanwhile, FoxP3+ TIL was not an independent prognostic factor for OS or PFS in the MVA (Table 2, Fig. 2C, D).

Figure 2.

Kaplan-Meier curves of A) overall survival and B) progression-free survival for patients stratified for high and low numbers of tumor-infiltrating CD8+ T cells; Kaplan-Meier curves of C) overall survival and D) progression-free survival for patients stratified for high and low numbers of tumor-infiltrating FOXP3+ T cells; Kaplan-Meier curves of E) overall survival and F) progression-free survival in PD-L1 negative and PD-L1 positive patients (1% cutoff level).

For the limited sample size of PD-L1 patients, we didn't put the PD-L1 expression into MVA. It is observed that OS of PD-L1+ patients was significantly improved (1% cutoff level) or had a trend of improvement (5% cutoff level) compared with PD-L1- patients (3-year OS, 1%+, 84.4% vs. 45.0%, p = 0.02; 5%+, 89.5% vs. 56.5%, p = 0.07) (Fig. 2E, Fig. S2A). However, PFS of PD-L1+ and PD-L1- patients was not significantly different (3-year PFS, 1%+, 59.3% vs. 40.0%, p = 0.32; 5%+, 63.2% vs. 44.4%, p = 0.48) (Fig. 2F, Fig. S2B).

Subgroup analysis according to p16 status

The p16-positive subgroup patients (n = 21) had more favorable outcomes compared with p16-negative sub-group patients (n = 56) in 5-year OS (95.0% vs. 39.0%, p < 0.001) and PFS (76.2% vs. 33.6%, p = 0.003).

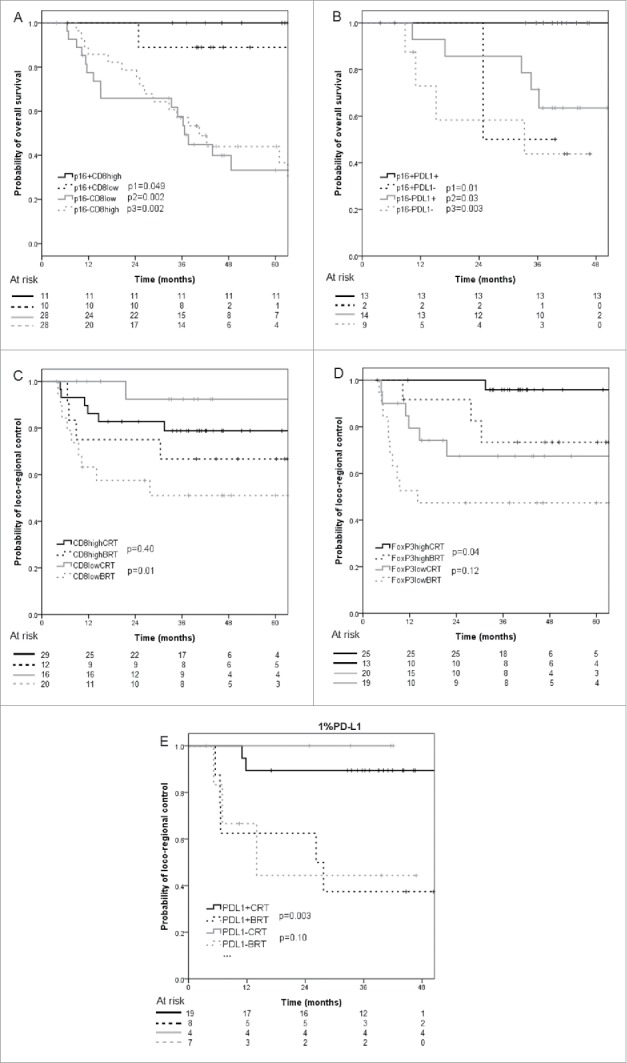

In subgroup analysis, p16+/high CD8+TILs patients had improved 5-year OS (100%) compared with p16+/low CD8+TILs (88.9%, p = 0.049), p16-/ high CD8+TILs (44.0%, p = 0.002), and p16-/ low CD8+TILs patients (33.2%, p = 0.002) (Fig. 3A). Similarly, using 1% cutoff level, p16+/PD-L1+ patients had improved 3-year OS (100%) compared with p16+/PD-L1- (50.0%, p = 0.01), p16-/ PD-L1+ (71.4%, p = 0.03), p16-/ PD-L1- (43.7%, p = 0.003) (Fig. 3B).

Figure 3.

Kaplan-Meier curves of overall survival according to A) CD8+ immune cells infiltration and B) PD-L1 expression (1% cutoff level) in HPV/p16 positive and HPV/p16 negative patients; C) Kaplan-Meier curves of locoregional control according to CD8+ immune cells infiltration in patients receiving concurrent chemoradiotherapy or bioradiotherapy; D) Kaplan-Meier curves of locoregional control according to FoxP3+ immune cells infiltration in patients receiving concurrent chemoradiotherapy or bioradiotherapy. E) Kaplan-Meier curves of locoregional control according to PD-L1 status (1% cutoff level) in patients receiving concurrent chemoradiotherapy or bioradiotherapy.

Subgroup analysis according to treatment option

In high CD8+ infiltrates tumors, 5-year LRC of patients treated with CRT was not significantly different with those treated with BRT (78.8% vs. 66.7%, p = 0.40), while in low CD8+ infiltrates tumors, CRT achieved better 5-year LRC in comparison with BRT (92.3% vs. 51.0%, p = 0.01) (Fig. 3C). However, 5-year OS and PFS of patients treated with CRT was not significantly different with those treated with BRT either in high (OS, 57.9% vs. 81.8%, p = 0.35; PFS, 47.5% vs. 66.7%, p = 0.46) or low CD8+ infiltrates tumors (OS, 43.3% vs. 35.4%, p = 0.38; PFS, 39.4% vs. 29.5%, p = 0.24).

In high FoxP3+ infiltrates tumors, 5-year LRC of patients treated with CRT was improved vs. those with BRT (95.8% vs. 73.3%, p = 0.04), while in low FoxP3+ infiltrates tumors, 5-year LRC was not significantly different between the 2 treatment subgroups (67.4% vs. 47.4%, p = 0.12) (Fig. 3D). Five-year OS and PFS of patients treated with CRT was not significantly different with those treated with BRT either in high (OS, 60.8% vs. 77.9%, p = 0.57; PFS, 53.1% vs. 55.6%, p = 0.92) or low FoxP3+ infiltrates tumors (OS, 42.9% vs. 39.0%, p = 0.50; PFS, 33.3% vs. 36.8%, p = 0.56).

In PD-L1+ (1%) tumors, 3-year LRC of patients treated with CRT was improved vs. those with BRT (89.5% vs. 37.5%, p = 0.003), while in PD-L1- tumors, 3-year LRC was not significantly different between the 2 treatment subgroups (100% vs. 44.4%, p = 0.10) (Fig. 3E). Three-year OS and PFS of patients treated with CRT was not significantly different with those treated with BRT either in PD-L1+ (OS, 83.9% vs. 85.7%, p = 0.76; PFS, 68.4% vs. 37.5%, p = 0.14) or PD-L1- tumors (OS, 50.0% vs. 41.7%, p = 0.50; PFS, 50.0% vs. 33.3%, p = 0.33). The same tendency of OS and PDF was observed when comparing CRT vs. BRT according to PD-L1 expression using the 5% cutoff level. Three-year LRC of patients treated with CRT was improved vs. those with BRT either in PD-L1+ (85.7% vs. 40.0%, p = 0.03) or PD-L1- (100% vs. 40.0%, p = 0.01) patients.

Discussion

It is generally accepted that the immune system plays a pivotal role in cancer. Our study demonstrated that high CD8+ TILs was independently correlated with better OS and PFS for HNSCC. However, we could not demonstrate a significant independent association for FoxP3 TILs or PD-L1 expression with patients' survival outcomes in MVA.

TILs have been demonstrated to be key players in the host's immune response to the tumor. Evaluation of the dynamics and functional roles of different subsets of TILs in the tumor suppressive microenvironment could facilitate our better understanding of immunopathogenesis of cancer and the development of effective strategies for anti-tumor immunotherapy. The most consistently beneficial TILs seem to be cytotoxic CD8+ lymphocytes, which have been shown in studies of multiple cancer types to be prognostic, including HNSCC.10 The results of our Immunohistochemistry (IHC) evaluation of CD8+ infiltrates are in agreement with former studies with a significantly increased density in HPV-positive than in HPV-negative sub-population,1,11,12 which suggests a stronger anti-tumoral immune response in HPV+ HNSCC. This may be an important reason that the HPV+ patients have a better clinical outcome in comparison to HPV- patients. Meanwhile, in the subgroup survival analyses, it is observed that p16+/high CD8+ TILs patients had superior overall survival in comparison to each of the rest subgroups of patients. Although HPV status is acknowledged to be the strongest prognostic marker in HNSCC patients,13 the search for additional biomarkers is ongoing for further risk stratification and treatment personalization. As an independent prognostic biomarker adjusted for HPV status, CD8+ TILs could provide complementary information for de-intensification treatment-population selection in the HPV+ patients, and potentially lead to improvement of quality of life of these patients with very favorable prognosis.

Meanwhile, recent studies have shown inconsistent findings regarding the prognostic performance of CD8+ TILs in different micro-environment localization. In a German multicenter study of patients with head and neck cancer after postoperative chemoradiotherapy, the prognostic significance of CD8 TILs based on the 3 separate tumor compartments (tumor periphery, tumor stroma and tumor cell) were examined, and high CD8 score in all 3 compartments predicted for better outcome.14 On the other hand, Oguejiofor et al. reported that only CD3+CD8+ stromal and not tumor area infiltration was associated with increased survival.15 Comprehensive assessment of differential infiltration of CD8+ TILs in different tumor compartments merits further study.

The role of FoxP3+ regulatory T cells (Tregs) in cancer remains highly controversial.8,16 Whether it is part of an immunosuppressive network promoting tumor immunity or a protective mechanism controlling cancer-associated inflammation or both is still under investigation. One pooled analysis including 17 types of cancer (15512 cancer cases) suggested FoxP3+Tregs had a significant negative effect on OS (OR 1.46, P < 0.001). However, the role of Tregs in cancer is multi-faceted and is influenced significantly by cancer type, stage and location, in addition to the unique immune landscape and tumor microenvironment of each cancer.8,17,18 Our results showed a positive association between HPV/p16 status and intensity of FoxP3+ Tregs. The same trend, HPV-positive head and neck cancers more heavily infiltrated by regulatory T cells, was reported by Badoual et al.19 High FoxP3+ Tregs correlated with a favorable OS and PFS in UVA but not in MVA. Badoual et al. showed that the level of tumor-infiltrating Tregs in head and neck cancer is positively-correlated with locoregional control, which may be through downregulation of harmful inflammatory reaction which contributes to cancer initiation and progression.20-22 In head and neck cancers, HPV infection was one of the initial inflammations contributing to neoplastic transformation. Besides, HPV associated cancer or not, both are permanently exposed to microbiological agents from oral cavity. Thus, by suppressing inflammation and immune responses resulting from HPV viral invasion, Foxp3+ Tregs could be anti-tumorigenic in HNSCC. On the other hand, FoxP3+ Tregs suppress cytotoxic T cell activity through the generation of various immunosuppressive cytokines thus they contribute to tumor progression.8 In addition, Tregs was shown to be resistant to radiation in mouse models of lung and colon cancer.23 Therefore, the prognostic value of the FoxP3+ Tregs may be the result of complex cross-talk between systemic inflammation and the immune response in a tumor-specific environment.

With the recent unprecedented success of anti PD-1/PD-L1 antibodies for cancer treatment, much of the attention have been given to characterize PD-L1 expression to find out whether it could be used as a prognostic or predictive biomarker. PD-L1 mediates inhibition of the immunological defense and theoretically it can be hypothesized that its high expression may result in poor overall survival. However, the variable association of PD-L1 expression with survival in treatment naïve cohorts may be attributed to its adaptive expression in response to an effective host immune system. PD-L1 expression is upregulated under inflammatory conditions triggered by several cytokines, especially by T-cell secreted IFNγ, and patients with T-cell rich tumors expressing PD-L1 are likely to have better immune surveillance.24 Radiation can release tumor antigen, and increase tumor antigen presentation, priming of cytotoxic T cells, as well as enhanced T-cell homing, engraftment and function in tumors. Radiotherapy can positively interact with immunotherapies in inducing a sustained abscopal effect.25,26 A recent study of 260 operated primary laryngeal squamous cell carcinoma patients with/without radiotherapy showed that TILs density correlated with tumor PD-L1 protein expression. Both high TILs and PD-L1 level was independently associated with better disease-free survival and OS in multivariate analysis.27 Meanwhile, in another study PD-L1 status was not associated with disease-free, disease-specific or overall survival on UVA in 217 oral squamous cell carcinoma.28 Our UVA showed significant difference of OS between PD-L1+ and PD-L1- patients but densities of CD8 and FoxP3 infiltrates were not significantly different between PD-L1+ and PD-L1− patients. Literature regarding the prognostic value of PD-L1 is confounded by various types of malignancies, different forms of therapy, methods used to evaluate PD-L1, the definition of positive expression, staining intensities, and staining distributions.24 The favorable prognostic value of PD-L1 on immune cells, but not tumor cells, in resected HNSCC has been reported by Kim et al.29 In our study, using 2 different cutoff levels (5% and 1%), both positive PD-L1 expressions was associated with improved OS on UVA. However, our small number of sample size restricts the interpretation of these findings, and further validation with large cohort size may yield more definitive results. Given the recognized importance of HPV in the etiology of HNSCC, studies have also been performed to correlate expression of PD-L1 with HPV status. No difference of PD-L1 positivity was observed between HPV/p16+ and HPV/p16- patients in the present study. As reported by Lyford-Pike et al., HPV+ patients had a higher expression of PD-L1 than HPV- patients (70% vs. 29%).30 In the study of Ukpo et al., oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma expressing B7-H1 was more likely to be HPV positive (49.2 vs. 34.1%, p = 0.08).31 However, in the recent published KEYNOTE-012 expansion cohort, PD-L1 has been shown to be overexpressed in both settings in patients with recurrent/metastatic HNSCC.32 The contradictive results can be attributed to different techniques used to evaluate PD-L1 expression and interpretative uncertainties including positivity cutoff and tumor heterogeneity and dynamic changes of PD-L1 expression.28

Cetuximab associated with radiotherapy is one of the treatment options for HNSCC. In addition to targeting epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) to induce tumor cell growth, another mechanism of action of cetuximab is considered to be antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity (ADCC).33 Cetuximab forms a bridge between tumor cells and immune cells when it is attached to the EGFR.34 Although evidences are emerging comparing CRT versus BRT for treating locally advanced HNSCC, so far published results are controversial.35 Characterization of the optimal selection of patients benefiting from concurrent cisplatin or cetuximab has yet to be defined. It is generally accepted that there is an immune suppressive micro-environment in HNSCC tumors.34 In oral squamous cell carcinoma, cisplatin based chemoradiotherapy was shown to drive the composition of inflammatory cells in a direction which is supposed to be prognostically favorable. CD8+ cytotoxic T cells decreased slightly while regulatory T cells decreased much more intensely after CRT.36 Meanwhile, cetuximab could enhance EGFR-specific cytotoxic CD8+ T-cell–based immunity through the immunologic effects on natural killer (NK) cells and DC, which lead to increased DC maturation and tumor antigen processing.33 It is hypothesized that cetuximab which is a potentially less intensive treatment regimen compared with cisplatin could achieve similar efficacy in the subpopulations of which the prognosis is more favorable.37 Our exploratory biomarker analysis implied that patients with pretreatment low CD8+ TILs or high FoxP3+ Tregs or PD-L1+ benefited more from CRT compared with BRT in LRC, while equivalent efficacy was observed with cisplatin vs cetuximab in tumors with high CD8+ TILs, low FoxP3+ Tregs or PD-L1-. This could be used to select optimal treatment choice for a certain sub-population. Future studies testing both pre- and post-treatment immune cell expression levels and their correlation with patients' survival outcomes is warranted to provide information for selecting suitable patients for cisplatin or cetuximab treatment.

Our study has several limitations. First, it is a single center, retrospective study with limited sample size of tested PD-L1 information, which may lead to low statistical power that has a reduced chance of detecting a true difference. The low number of patients and events in the PD-L1 information-available group did not allow for MVA and further sub-group analysis. On the other hand, multiple associations tested in the study might lead to a high risk of false positive results. Secondly, also due to the retrospective nature, the fixation method of biopsies was not uniform, which could potentially affect the IHC evaluation results. Further, assessing immune biomarkers in small samples of tumor tissue might not well represent the entire tumor, as they are not expressed uniformly within tumors but rather at sites of lymphocyte infiltration.

In conclusion, a well annotated cohort of HNSCC patients was investigated for the presence of immune markers, including CD8, FoxP3 and PD-L1 expression. Densities of CD8 and FoxP3 infiltrates were higher in HPV/p16+ tumors compared with HPV/p16− tumors. High CD8+ TIL level was an independent prognostic factor independent of HPV/p16status. CD8+ TILs and PD-L1 expression could provide complementary information to HPV status in selecting subpopulation for treatment de-intensification. These 3 immunobiomarkers may provide information for selecting suitable patients for cisplatin or cetuximab treatment. Future studies will need to validate these findings in a larger prospective/independent cohort as well as further investigating the detailed mechanisms.

Patients and methods

Patients and tissues

Patients were selected from the former study cohort of 265 patients with pathologically-confirmed HNSCC, diagnosed between 2006 and 2012 in our institute (CRT: n = 194, BRT: n = 71).37,38 Patients with stage III–IVb disease according to American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC)/ International Union for Cancer Control (UICC) TNM classification 2010, received total radiation dose of 70Gy, ≥2 cycles of concurrent CDDP or ≥3 cycles of concurrent cetuximab were selected from the initial cohort. A matched control subset of patients treated with CRT vs. BRT (2:1 ratio) was then identified. Matching criteria were (1) T stage, (2) N stage. If the matching criteria could not be fulfilled, the case was not included in the study. Thus 120 eligible patients were included for analyses of biomarkers. Finally, 38 patients had evaluable PD-L1 results. Seventy-seven patients had both evaluable CD8 and FoxP3 results, 31 of whom had PD-L1 analysis results. Fig. S3 is the diagram of patient selection for the study.

Investigations were performed on paraffin-embedded pretreatment biopsy material which had been fixed in either formalin (N = 41) or formalin-acetic acid-alcohol (FAA) (N = 36, patients treated before 2010). All pretreatment biopsy slides were reviewed by an experienced pathologist (I.G.). HPV status was determined through p16 immunohistochemistry (IHC) using CINtec® assay (CINtec P16 INK4A, Ventana, Tucson, AZ, USA). We considered p16 as positive when a nuclear staining was present in > 75% of cells; cytoplasmic only staining was considered as negative.

Institutional research ethics board approval was obtained. Written informed consent was obtained from included patients. All patients received either one of the following 2 treatments: definitive radiotherapy concomitantly with cisplatin (100 mg/m2 every 3 weeks on days 1, 22, and 43) or cetuximab (initial loading dose of 400 mg/m2 one week before RT, followed by weekly injection at 250 mg/m2 during RT). Patients received either 3-dimensional conformal radiotherapy (3D-CRT) or intensity-modulated radiotherapy (IMRT). External beam definitive RT was delivered with a total dose of 70 Gy to the gross tumor volume (GTV) in 35 fractions (range 30–35 fractions) at 5 fractions per week, with median overall treatment time of 49 d (range 39–70 days). A dose of 60 Gy and 50–54 Gy were delivered to the intermediate- and low-risk clinical target volume (CTV). The CTVs were each expanded using 3–5 mm margins to generate their respective planning target volumes (PTV). Patient assessments in follow-up were described previously.37

Immunohistochemistry

Three-µm thick sections from formalin- or FFA-fixed paraffin-embedded samples were prepared and dehydrated. CD8 expression was detected by using a monoclonal rabbit anti-CD8 antibody (clone SP16, M3164, Spring Bioscience, Pleasanton, CA, USA) at a dilution of 1:100. FoxP3 expression was determined with a polyclonal rabbit anti-FoxP3 antibody (M3974, Spring Bioscience, Pleasanton, CA, USA) at a dilution of 1:100. PD-L1 expression was quantified by using a rabbit anti-PD-L1 antibody (clone E1L3N, Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA, USA) at 1:1500 dilution on a Ventana Discovery Ultra autostainer. Human tonsil sections were used as positive controls for CD8, FOXP3 and PD-L1. Negative control was performed by omitting the primary antibody (Fig. S4). All assessments were performed independently by 2 pathologists (I. G. and J. A.), blinded to the clinical and follow-up data. Discordances were resolved by consensus review.

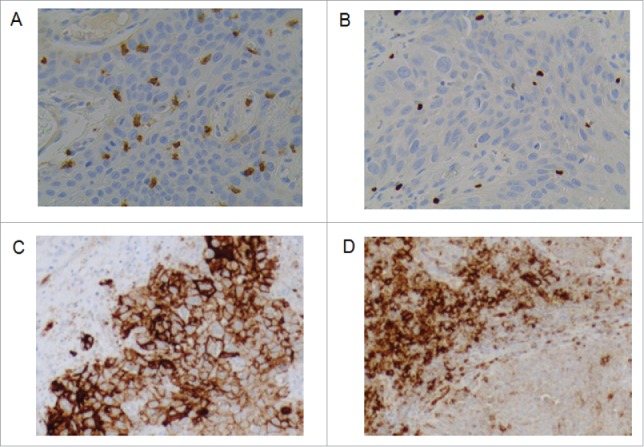

For CD8 and FoxP3 staining, whole slides were digitized under high-power magnification (x20) with a slide scanner VS120-SL (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) enabling whole slide quantification. Computer assisted image analysis was conducted. CD8 slides were processed with Definiens Developer XD (Definiens, Munich, Germany) and FoxP3 slides were processed with Definiens Architect XD (Definiens, Munich, Germany). The density of TILs was expressed as the mean number of stained cells per square millimeter of the chosen areas (in the tumor site and in the surrounding healthy tissue.) (Fig. 4A, B).

Figure 4.

Representative picture of immunohistochemical staining image using A) CD8 and B) FOXP3 specific antibody (400X). Positive cells are stained brown. The exact number of CD8+ and FOXP3+ lymphocytes was evaluated in the tumor site and in the surrounding healthy tissue. C) D) Representative picture of immunohistochemical staining image using PD-L1 specific antibody (200X). Positive cells are stained brown. C) PD-L1 tumor cells positive D) PD-L1 immune cells positive.

Two scoring cutoff levels were used to assess PD-L1 expression prevalence. PD-L1 IHC staining on both TC and tumor-infiltrating immune cells IC was quantified with a positivity threshold of ≥1% or ≥5% (Fig. 4C, D).

Statistics

CD8+ and FoxP3+ TILs expressed in different subgroups of pretreatment characteristics were compared using the Mann–Whitney U test as these continuous variables were non-normally distributed. The associations between PD-L1 expression and the other pretreatment parameters were analyzed using a chi-square test. Survival rates were calculated with the Kaplan–Meier method and compared using the log-rank test. Survival times were defined as the time from the beginning of radiotherapy until either the time of first event or the date that the patient was last known to be alive (censored). Events were death from any cause for OS, death or tumor progression for PFS, locoregional recurrence for LRC, and distant metastasis for DC. Pearson's correlation was used to test the relationship between CD8+ and FoxP3+ lymphocyte infiltrates. The Cox proportional hazard model was used for multiple regression analysis. Two-sided p values < 0.05 were considered to indicate a significant difference. All statistics were performed using SPSS version 18.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) and R software version 3.2.4.

Supplementary Material

Disclosure of potential conflicts of interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

Funding

This work was supported by EU 7th framework program (ARTFORCE), No grant number is applicable; and China Scholarship Council (CSC) under Grant 201406105021.

References

- 1.Krupar R, Robold K, Gaag D, Spanier G, Kreutz M, Renner K, Hellerbrand C, Hofstaedter F, Bosserhoff AK. Immunologic and metabolic characteristics of HPV-negative and HPV-positive head and neck squamous cell carcinomas are strikingly different. Virchows Arch 2014; 465 (3):299-312; PMID:25027580; https://doi.org/ 10.1007/s00428-014-1630-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mirghani H, Amen F, Tao Y, Deutsch E, Levy A. Increased radiosensitivity of HPV-positive head and neck cancers: Molecular basis and therapeutic perspectives. Cancer Treat Rev 2015; 41(10):844-52; PMID:26476574; https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.ctrv.2015.10.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kroemer G, Galluzzi L, Kepp O, Zitvogel L. Immunogenic cell death in cancer therapy. Annu Rev Immunol 2013; 31:51-72; PMID:23157435; https://doi.org/ 10.1146/annurev-immunol-032712-100008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Balermpas P, Rödel F, Rödel C, Krause M, Linge A, Lohaus F, Baumann M, Tinhofer I, Budach V, Gkika E, et al.. CD8+ tumour-infiltrating lymphocytes in relation to HPV status and clinical outcome in patients with head and neck cancer after postoperative chemoradiotherapy: A multicentre study of the German cancer consortium radiation oncology group (DKTK-ROG). Int J Cancer 2016; 138(1):171-81; PMID:26178914; https://doi.org/ 10.1002/ijc.29683 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Huang Y, Ma C, Zhang Q, Ye J, Wang F, Zhang Y, Hunborg P, ?Varvares MA, Hoft DF, Hsueh EC, et al.. CD4+ and CD8+ T cells have opposing roles in breast cancer progression and outcome. Oncotarget 2015; 6(19):17462-78; PMID:25968569; https://doi.org/ 10.18632/oncotarget.3958 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Donnem T, Hald SM, Paulsen E-E, Richardsen E, Al-Saad S, Kilvaer TK, Brustugun OT, Helland A, Lund-Iversen M, Poehl M, et al.. Stromal CD8+ T-cell density–A promising supplement to TNM staging in non-small cell lung cancer. Clin Cancer Res 2015; 21(11):2635-43; PMID:25680376; https://doi.org/ 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-14-1905 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gabrielson A, Wu Y, Wang H, Jiang J, Kallakury B, Gatalica Z, Reddy S, Kleiner D, Fishbein T, Johnson L, et al.. Intratumoral CD3 and CD8 T-cell Densities Associated with Relapse-Free Survival in HCC. Cancer Immunol Res 2016; 4(5):419-30; PMID:26968206; https://doi.org/ 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-15-0110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shang B, Liu Y, Jiang S, Liu Y. Prognostic value of tumor-infiltrating FoxP3+ regulatory T cells in cancers: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci Rep 2015; 5:15179; PMID:26462617; https://doi.org/ 10.1038/srep15179 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ferris RL, Blumenschein G, Fayette J, Guigay J, Colevas AD, Licitra L, Harrington K, Kasper S, Vokes EE, Even C, et al.. Nivolumab for Recurrent Squamous-Cell Carcinoma of the Head and Neck. N Engl J Med 2016; 375(19):1856-67; PMID:27718784; https://doi.org/ 10.1056/NEJMoa1602252 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wallis SP, Stafford ND, Greenman J. Clinical relevance of immune parameters in the tumor microenvironment of head and neck cancers: Clinical Relevance of Immune Parameters in the Tumor Microenvironment. Head Neck 2015; 37(3):449-59; PMID:24803283; https://doi.org/ 10.1002/hed.23736 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Näsman A, Romanitan M, Nordfors C, Grün N, Johansson H, Hammarstedt L, Marklund L, Munck-Wikland E, Dalianis T, Ramqvist T. Tumor Infiltrating CD8+ and Foxp3+ lymphocytes correlate to clinical outcome and Human Papillomavirus (HPV) status in tonsillar cancer. PLoS One 2012; 7:e38711; PMID:22701698; https://doi.org/ 10.1371/journal.pone.0038711 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Partlová S, Bouček J, Kloudová K, Lukešová E, Zábrodský M, Grega M, Fučíková J, Truxová I, Tachezy R, Špíšek R, et al.. Distinct patterns of intratumoral immune cell infiltrates in patients with HPV-associated compared to non-virally induced head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Oncoimmunology 2015; 4(1):e965570; PMID:25949860; https://doi.org/ 10.4161/21624011.2014.965570 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lassen P. The role of Human papillomavirus in head and neck cancer and the impact on radiotherapy outcome. Radiother Oncol 2010; 95(3):371-80; PMID:20493569; https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.radonc.2010.04.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Balermpas P, Rödel F, Rödel C, Krause M, Linge A, Lohaus F, Baumann M, Tinhofer I, Budach V, Gkika E, et al.. CD8+ tumour-infiltrating lymphocytes in relation to HPV status and clinical outcome in patients with head and neck cancer after postoperative chemoradiotherapy: A multicentre study of the German cancer consortium radiation oncology group (DKTK-ROG). Int J Cancer 2016. Jan 1; 138(1):171-81; PMID:26178914; https://doi.org/ 10.1002/ijc.29683 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Oguejiofor K, Hall J, Slater C, Betts G, Hall G, Slevin N, Dovedi S, Stern PL, West CM. Stromal infiltration of CD8 T cells is associated with improved clinical outcome in HPV-positive oropharyngeal squamous carcinoma. Br J Cancer 2015; 113(6):886-93; PMID:26313665; https://doi.org/ 10.1038/bjc.2015.277 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rakebrandt N, Littringer K, Joller N. Regulatory T cells: balancing protection versus pathology. Swiss Med Wkly 2016; 146:w14343; PMID:27497235; https://doi.org/ 10.4414/smw.2016.14343 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.deLeeuw RJ, Kost SE, Kakal JA, Nelson BH. The prognostic value of FoxP3+ Tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes in cancer: A critical review of the literature. Clin Cancer Res 2012; 18(11):3022-9; PMID:22510350; https://doi.org/ 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-3216 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fridman WH, Pagès F, Sautès-Fridman C, Galon J. The immune contexture in human tumours: Impact on clinical outcome. Nat Rev Cancer 2012; 12(4):298-306; PMID:22419253; https://doi.org/ 10.1038/nrc3245 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Badoual C, Hans S, Merillon N, Van Ryswick C, Ravel P, Benhamouda N, Levionnois E, Nizard M, Si-Mohamed A, Besnier N, et al.. PD-1-expressing tumor-infiltrating T cells are a favorable prognostic biomarker in HPV-associated head and neck cancer. Cancer Res 2013; 73(1):128-38; PMID:23135914; https://doi.org/ 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-2606 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Badoual C, Hans S, Rodriguez J, Peyrard S, Klein C, Agueznay Nel H, Mosseri V, Laccourreye O, Bruneval P, Fridman WH, et al.. Prognostic value of Tumor-Infiltrating CD4+ T-cell subpopulations in head and neck cancers. Clin Cancer Res 2006; 12(2):465-72; PMID:16428488; https://doi.org/ 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-1886 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Erdman SE, Rao VP, Olipitz W, Taylor CL, Jackson EA, Levkovich T, Lee CW, Horwitz BH, Fox JG, Ge Z, et al.. Unifying roles for regulatory T cells and inflammation in cancer. Int J Cancer 2010; 126(7):1651-65; PMID:19795459; https://doi.org/ 10.1002/ijc.24923 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chaudhary B, Elkord E. Regulatory T cells in the tumor microenvironment and cancer progression: Role and therapeutic targeting. Vaccines 2016; 4(3):28. pii:E28; PMID:27509527; https://doi.org/ 10.3390/vaccines4030028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Son CH, Bae JH, Shin DY, Lee H-R, Jo W-S, Yang K, Park YS. Combination effect of regulatory T-cell depletion and ionizing radiation in mouse models of lung and colon cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol 2015; 92(2):390-8; PMID:25754628; https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2015.01.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ritprajak P, Azuma M. Intrinsic and extrinsic control of expression of the immunoregulatory molecule PD-L1 in epithelial cells and squamous cell carcinoma. Oral Oncol 2015; 51(3):221-8; PMID:25500094; https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2014.11.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Levy A, Chargari C, Marabelle A, Perfettini J-L, Magné N, Deutsch E. Can immunostimulatory agents enhance the abscopal effect of radiotherapy? Eur J Cancer 2016; 62:36-45; PMID:27200491; https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.ejca.2016.03.067 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sharabi AB, Lim M, DeWeese TL, Drake CG. Radiation and checkpoint blockade immunotherapy: radiosensitisation and potential mechanisms of synergy. Lancet Oncol 2015; 16(13):e498-509; PMID:26433823; https://doi.org/ 10.1016/S1470-2045(15)00007-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vassilakopoulou M, Avgeris M, Velcheti V, Kotoula V, Rampias T, Chatzopoulos K, Perisanidis C, Kontos CK, Giotakis AI, Scorilas A, et al.. Evaluation of PD-L1 Expression and Associated Tumor-Infiltrating Lymphocytes in Laryngeal squamous cell carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res 2016; 22(3):704-13; PMID:26408403; https://doi.org/ 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-15-1543 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Satgunaseelan L, Gupta R, Madore J, Chia N, Lum T, Palme CE, Boyer M, Scolyer RA, Clark JR. Programmed cell death-ligand 1 expression in oral squamous cell carcinoma is associated with an inflammatory phenotype. Pathology 2016; 48(6):574-80; PMID:27590194; https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.pathol.2016.07.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kim HR, Ha SJ, Hong MH, Heo SJ, Koh YW, Choi EC, Kim EK, Pyo KH, Jung I, Seo D, et al.. PD-L1 expression on immune cells, but not on tumor cells, is a favorable prognostic factor for head and neck cancer patients. Sci Rep 2016; 6:36956; PMID:27841362; https://doi.org/ 10.1038/srep36956 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lyford-Pike S, Peng S, Young GD, Taube JM, Westra WH, Akpeng B, Bruno TC, Richmon JD, Wang H, Bishop JA, et al.. Evidence for a role of the PD-1:PD-L1 pathway in immune resistance of HPV-associated head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer Res 2013(6); 73:1733-41; PMID:23288508; https://doi.org/ 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-2384 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ukpo OC, Thorstad WL, Lewis JS Jr. B7-H1 expression model for immune evasion in human papillomavirus-related oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma. Head Neck Pathol 2013; 7(2):113-21; PMID:23179191; https://doi.org/ 10.1007/s12105-012-0406-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chow LQM, Haddad R, Gupta S, Mahipal A, Mehra R, Tahara M, Berger R, Eder JP, Burtness B, Lee SH, et al.. Antitumor Activity of Pembrolizumab in Biomarker-Unselected Patients With Recurrent and/or metastatic head and neck squamous cell carcinoma: Results From the Phase Ib KEYNOTE-012 Expansion Cohort. J Clin Oncol 2016; 34(32):3838-45; pii: JCO681478; PMID:27646946; https://doi.org/ 10.1200/JCO.2016.68.1478 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Srivastava RM, Lee SC, Andrade Filho PA, Lord CA, Jie H-B, Davidson HC, López-Albaitero A, Gibson SP, Gooding WE, Ferrone S, et al.. Cetuximab-activated natural killer and dendritic cells collaborate to trigger tumor antigen-specific T-cell immunity in head and neck cancer patients. Clin Cancer Res 2013; 19(7):1858-72; PMID:23444227; https://doi.org/ 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-2426 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rancoule C, Vallard A, Espenel S, Guy J-B, Xia Y, El Meddeb Hamrouni A, Rodriguez-Lafrasse C, Chargari C, Deutsch E, Magné N. Immunotherapy in head and neck cancer: Harnessing profit on a system disruption. Oral Oncol 2016; 62:153-162; PMID:27623508; https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2016.09.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Husain ZA, Burtness BA, Decker RH. Cisplatin Versus Cetuximab with radiotherapy in locally advanced squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck. J Clin Oncol 2016; 34(5):396-8; PMID:26644528; https://doi.org/ 10.1200/JCO.2015.64.7586 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tabachnyk M, Distel LVR, Büttner M, Grabenbauer GG, Nkenke E, Fietkau R, Lubgan D. Radiochemotherapy induces a favourable tumour infiltrating inflammatory cell profile in head and neck cancer. Oral Oncol 2012; 48(7):594-601; PMID:22356894; https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2012.01.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ou D, Levy A, Blanchard P, Nguyen F, Garberis I, Casiraghi O, Scoazec JY, Janot F, Temam S, Deutsch E, et al.. Concurrent chemoradiotherapy with cisplatin or cetuximab for locally advanced head and neck squamous cell carcinomas: does human papilloma virus play a role? Oral Oncol 2016; 59C:50-7; PMID:27424182; https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2016.05.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Levy A, Blanchard P, Bellefqih S, Brahimi N, Guigay J, Janot F, Temam S, Bourhis J, Deutsch E, Daly-Schveitzer N, et al.. Concurrent use of cisplatin or cetuximab with definitive radiotherapy for locally advanced head and neck squamous cell carcinomas. Strahlenther Onkol 2014; 190(9):823-31; PMID:24638267; https://doi.org/ 10.1007/s00066-014-0626-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.