ABSTRACT

Surgery is the only potentially curative option for patients with pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC), but metastatic relapse remains common. We hypothesized that the expression levels of inflammatory cytokines could predict recurrence of PDAC, thus allowing to select patients who most likely could benefit from surgical resection.

We prospectively collected plasma at diagnosis from 287 patients with pancreatic resectable neoplasms. The expression levels of 23 cytokines were measured in 90 patients with PDAC by using a multiplex analyte profiling assay. Levels higher than cutoff identified of the TH2 cytokines interleukin (IL)4, IL5, IL6 of macrophage inflammatory protein (MIP)1α, granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF), and monocyte chemoattractant protein (MCP)1, and of IL17α, IFNγ-induced protein (IP)10, and IL1b were significantly associated with a shorter median OS. In particular, levels of IL4 and IP10 higher than cutoff identified, and level of TH1 cytokines TNFα and INFγ, and of IL9 and IL1Rα lower than cutoff identified were significantly associated with a shorter DFS. In the multivariate analysis, high IP10 was confirmed as negatively associated with OS (HR = 3.097, p = 0.014) and IL4 and TNFα remain negatively (HR = 2.75, p = 0.002) and positively (HR = 0.224, p = 0.049) associated with DFS, respectively. Simultaneous expression of low IL4 and high TNFα identified patients with best prognosis (HR = 0.313, p < 0.0001). In conclusion, we demonstrated that, among a series of cytokines, IL4 is the most significant independent prognostic factor for DFS in resectable PDAC patients, and it could be useful to select patients with high risk of early recurrence who may avoid an unnecessary resection.

KEYWORDS: circulating cytokine profile, IL4, pancreatic adenocarcinoma, prognostic biomarker, TH2 cytokines

Introduction

Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) is a deadly disease, with the lowest 5-y relative survival rate among solid tumors at 7%,1 and is projected to become the second leading cause of cancer-related death by 2030.2 Surgery is the only potentially curative option for PDAC patients, but metastatic relapse remains common and no more than 20% of patients undergoing surgery and post-surgical therapy achieve long-term survival.3 Thus, the identification of biologic markers able to predict metastatic recurrence of PDAC remains critical to select patients most likely to benefit from surgical resection.4

Tumor microenvironment contains both innate and adaptive immune cells that communicate with each other by means of cytokines and chemokines production to control tumor growth and spread.5 In this “immune contexture,” the cytokine expression profile may be more relevant than its specific immune cell content, and provide malignant cells with continuous supply of growth and survival signals.6-8

In PDAC, a dysfunctional immune system aids rather than controls cancer development and progression.9 However, it is still unclear which cytokines or chemokines are critical for metastasis and prognosis of established tumors.10 Previous studies examined the association between serum levels of several proinflammatory cytokines and overall survival (OS) in cohorts of patients with mostly advanced PDAC. In these studies, only a high level of IL6 was consistently demonstrated as an independent prognostic factor for poor OS.11-14 However, comprehensive cytokine profiles have not been performed in early PDAC to date, therefore it is still unclear the potential value of cytokines or chemokines in predicting recurrence in this disease.

Here, we investigated whether the preoperative expression levels of 23 cytokines in a large and prospective cohort of patients with resectable PDAC could be predictive of their Disease free survival (DFS) or OS, thus, serving as potential biomarker to select patients more likely to benefit from an upfront surgical resection.

Results

Association of patients' characteristics with OS and DFS

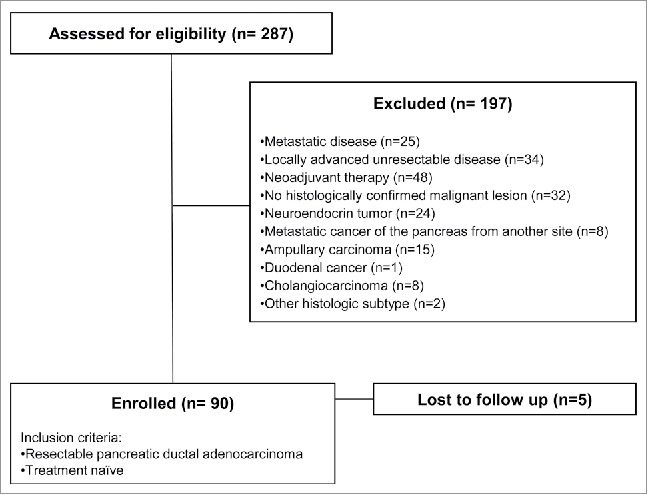

Two-hundred-eighty-seven patients admitted at the Unit of General and Pancreatic Surgery of the Azienda Ospedaliera Universitaria Integrata of Verona between 2012 and 2014 with suspected PDAC were assessed for eligibility. Among them, a total of 90 treatment-naïve resectable patients with histologically proven non-metastatic PDAC were included in the study (Fig. 1). Patients' characteristics are shown in Table 1. The mean age was 63 y and 51% were male. Most of them had tumors in the head of pancreas (79%), T3 stage (96%), and positive nodes (86%). Radical resection (R0) was obtained in 46% of cases. The majority of patients received adjuvant chemotherapy (82%), mostly with a gemcitabine-based regimen (97%). After a median follow-up of 26.9 mo, the median DFS was 19.9 mo and the median OS was not reached (data not show). Compliance with REMARK guidelines is reported in Table S1, available at Clinical Cancer Research online.

Figure 1.

Strobe diagram of the study.

Table 1.

Characteristics of patients involved in the study.

| Patients characteristics | N° | % | p (OS) | HR | p (DFS) | HR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (y) | ||||||

| Median | 63 | 0.319 | 1.572 | 0.772 | 1.088 | |

| Range | 37–77 | |||||

| Gender | ||||||

| Female, n (%) | 44 | 49 | ||||

| Male, n (%) | 46 | 51 | 0.784 | 0.892 | 0.1 | 0.626 |

| Tumor stage | ||||||

| T1, n (%) | 1 | 1 | ND | ND | ||

| T2, n (%) | 2 | 2 | ||||

| T3, n (%) | 86 | 96 | ||||

| T4, n (%) | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Nodal stage | ||||||

| N0, n (%) | 13 | 14 | ||||

| N+, n (%) | 77 | 86 | 0.441 | 1.768 | 0.408 | 1.435 |

| Metastasis stage | ||||||

| M0, n (%) | 90 | 100 | ||||

| M+, n (%) | 0 | 0 | ND | ND | ||

| Location | ||||||

| Head, n (%) | 71 | 79 | ||||

| Body/tail, n (%) | 19 | 21 | 0.490 | 0.720 | 0.346 | 0.732 |

| Resection margins | ||||||

| R0, n (%) | 41 | 46 | ||||

| R1, n (%) | 49 | 54 | 0.394 | 1.441 | 0.121 | 1.573 |

| Adjuvant therapy | ||||||

| No, n (%) | 16 | 18 | ||||

| Yes, n (%) | 74 | 82 | 0.157 | 0.510 | 0.038 | 0.502 |

| Non-gemcitabine based, n (%) | 2 | 3 | ||||

| Gemcitabine-based, n (%) | 72 | 97 | ND | ND | ||

| Radiotherapy | ||||||

| No, n (%) | 65 | 72 | ||||

| Yes, n (%) | 25 | 28 | 0.383 | 0.643 | 0.430 | 0.775 |

| Tumor grade | ||||||

| G1, n (%) | 7 | 8 | ||||

| G2, n (%) | 58 | 64 | ||||

| G3, n (%) | 25 | 28 | 0.001 | 3.986 | 0.012 | 2.109 |

HR, hazard ratio; R1, resection denotes a microscopically positive margin; T, Tumor; N, node; G, grade.

Univariate analysis of correlation between clinical features and OS or DFS is shown in Table 1. Among the clinical parameters analyzed, patients with poorly differentiated tumor (G3) had a significantly shorter OS (HR = 3.986, p = 0.001) and DFS (HR = 2.109, p = 0.012) compared with patients with well and moderately differentiated tumors (G1/G2). Conversely, patients treated with adjuvant therapy had a significantly longer DFS than did untreated patients (HR = 0.502, p = 0.038). Association between DFS and other commonly used prognostic parameters, such as microscopically infiltrated resection margins (R1) and positive lymph nodes (N+), although displayed a negative trend, was not statistically significant in this cohort (HR = 1.573, p = 0.121, and HR = 1.435, p = 0.408, respectively).

Association of circulating cytokines and chemokines levels with OS and DFS

To determine whether patterns of circulating cytokines and chemokines could predict patients outcome, we measured the concentration of a panel of 23 different TH1, TH2, TH9, TH17 cytokines, chemokines, and growth factors in preoperative plasma samples from 90 treatment naïve patients with non-metastatic PDAC (Table 2). The optimal cutoff thresholds able to significantly predict patients' outcome were evaluated for each cytokine (Table 2 and Fig. 2A and B).

Table 2.

Pre-surgical circulating cytokines levels significantly correlated with OS and DFS.

| Soluble factor | N° | mean pg/mL (Lower–upper 95%CI) | Median pg/mL (range) | Association with OS (p) | cutoff (pg/mL) | Association with DFS (p) | cutoff (pg/mL) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TH2 cytokines | |||||||

| IL4 | 90 | 9.739 (8.12–11.36) | 7.42 (1.28–45.48) | 0.025 | 9.365 | 0.01 | 9.365 |

| IL5 | 90 | 15.08 (11.64–18.52) | 9.31 (0–74.02) | 0.047 | 5.255 | 0.34 | — |

| IL6 | 90 | 36.8 (26.92–46.67) | 23.02 (2.96–319.2) | 0.038 | 23.92 | 0.41 | — |

| IL13 | 90 | 36.22 (29.2–43.25) | 28.63 (0.5–223.4) | 0.17 | — | 0.058 | — |

| TH1 cytokines | |||||||

| IFNγ | 90 | 574.4 (440.1–708.6) | 392.5 (10.8–3418) | 0.56 | — | 0.004 | 129 |

| IL12(p70) | 90 | 45.05 (30.01–60.1) | 27.63 (0–561.6) | 0.07 | — | 0.24 | — |

| TNFα | 90 | 94.17 (66.74–121.6) | 69.27 (0–1069) | 0.76 | — | 0.003 | 22.04 |

| IL2 | 90 | 21.22 (8.47–33.97) | 0 (0–426.2) | 0.14 | — | 0.096 | — |

| TH9 cytokines | |||||||

| IL9 | 90 | 39.22 (23.51–54.92) | 20.69 (0.3–610) | 0.66 | — | 0.021 | 5.48 |

| TH17 cytokines | |||||||

| IL17α | 90 | 175.6 (134.8–216.4) | 109.6 (0–913) | 0.03 | 360.4 | 0.59 | — |

| Chemokines | |||||||

| MIP1α | 90 | 6.44 (5.39–7.49) | 5.11 (0.8–34.68) | 0.042 | 10.14 | 0.37 | — |

| MCP1 | 90 | 129.3 (104.6–154) | 107.9 (10.31–809.7) | 0.032 | 109.3 | 0.15 | — |

| MIP1b | 90 | 107.3 (73.39–141.3) | 82.13 (26.81–1577) | 0.94 | — | 0.3 | — |

| IP10 | 90 | 1734 (1289–2179) | 1143 (376.2–17964) | 0.003 | 2958 | 0.04 | 2958 |

| IL8 | 90 | 79.2 (60.05–98.35) | 47.62 (8.85–484.6) | 0.14 | — | 0.054 | — |

| eotaxin | 90 | 175.1 (103.8–246.4) | 102.7 (0–2912) | 0.19 | — | 0.062 | — |

| Other cytokines and growth factors | |||||||

| G-CSF | 90 | 243.5 (191.4–295.5) | 155.9 (19.9–1076) | 0.17 | — | 0.064 | — |

| GM-CSF | 90 | 70.95 (50.91–91) | 49.48 (0–547.6) | 0.035 | 134 | 0.38 | — |

| VEGF | 90 | 82.82 (63.04–102.6) | 53.82 (0–471.9) | 0.17 | — | 0.9 | — |

| IL7 | 90 | 19.85 (15.88–23.83) | 14.17 (0–121.2) | 0.12 | — | 0.11 | — |

| IL15 | 90 | <OOR | <OOR | <OOR | — | <OOR | — |

| IL1β | 90 | 7.639 (5.526–9.751) | 5.255 (0–59.64) | 0.018 | 7.92 | 0.44 | — |

| IL1Rα | 90 | 715.1 (480–950.2) | 356 (4.44–8552) | 0.66 | — | 0.039 | 115.5 |

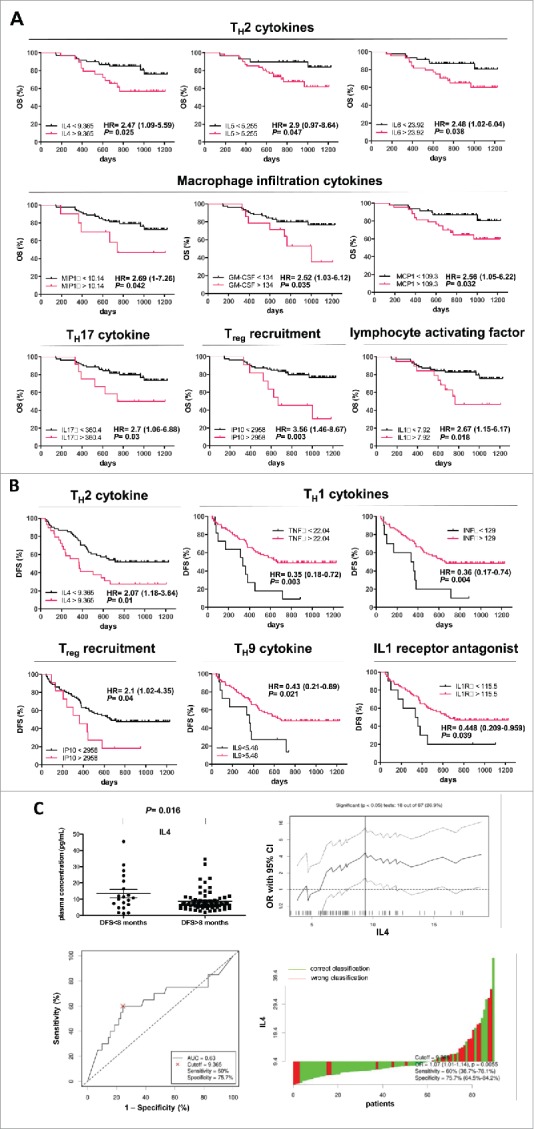

Figure 2.

OS and DFS of patients with PDAC stratified according to cytokines levels. Kaplan–Meier curves for OS (A) and DFS (B) by significant cytokines cutoff concentration in plasma samples. Cytokines concentration expressed as pg/mL. (C) upper left, IL4 level in patients stratified around an early relapse cutoff of 8 mo; upper right, determination of cutoff thresholds of IL4 level for PDAC patients dichotomized according to early relapse of 8 mo. All possible cutoff thresholds were considered and the corresponding odds ratios (OR) were calculated and plotted. Each data point in the line gives the corresponding OR and 95% confidence interval (dotted lines) on the y axis. Lower left, receiver operator characteristic (ROC) curves for IL4 level in patients stratified around early relapse cutoff of 8 mo; lower right, waterfall plot, green and red bars represent cases with correct or wrong classification, respectively.

Concentration of the TH2 cytokines IL4, IL5, IL6 of the monocyte/macrophage infiltration cytokines MIP1a, GM-CSF, and MCP-1, and of IL17a, IP10, and IL1b at level higher than cutoff were significantly associated with a shorter patient's median OS.

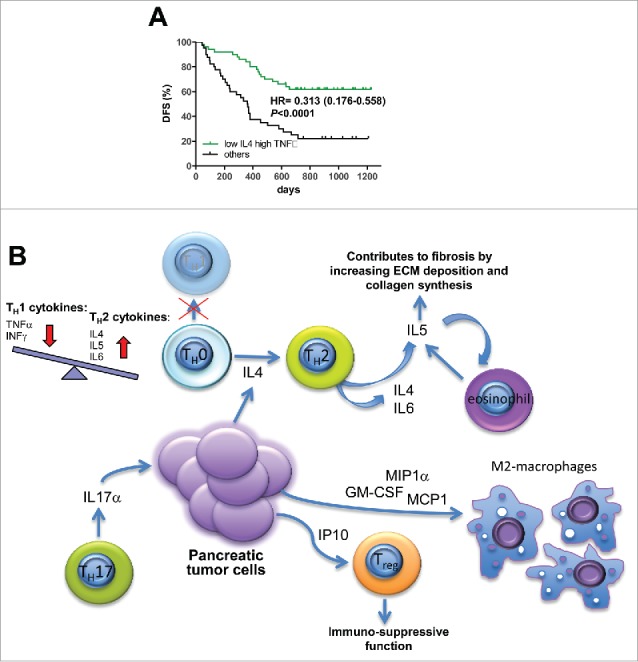

Concentration of IL4 and IP10 higher than cutoff were significantly associated with shorter median DFS. ON the contrary, concentration of TH1 cytokines TNFα and interferon (IFN)γ and of IL9 and IL1Ra higher than cutoff were significantly associated with an increased median DFS. A summary of the overall findings of the study is reported in Fig. 3B.

Figure 3.

Combined cytokine signature predicts DFS. (A) patients were stratified for DFS on the basis of simultaneous expression of low IL4 and high TNFα. (B) tumor-immune network.

An additional analysis demonstrated that patients whose DFS exceeded 8 mo had significantly less circulating IL4 level than did patients with DFS<8 mo (p = 0.016) (Fig. 2C). The optimal cutoff threshold of 9.365 pg/mL had a sensitivity of 60% (95% CI = 38.7%–78.1%) and a specificity of 75.7% (95% CI = 64.5%–84.2%). In particular, an early relapse within 8 mo occurred in 12 out of 29 (41.4%) patients with a plasma concentration of IL4 higher than cutoff, and only in 8 out of 61 (13.1%) patients with IL4 lower than cutoff. The same association was not proven for the other cytokines (Fig. S1, available at Clinical Cancer Research online).

Multivariate analysis of correlation between prognostic factors, including plasma cytokines, and OS and DFS

To confirm our findings and select the best prognostic cytokines, we performed a multivariate analysis including clinical features that had univariate significance (p < 0.05), and the most significant prognostic cytokines at univariate analysis (p < 0.01). In this analysis, high IP10 was confirmed as negatively associated with OS (HR = 3.097, p = 0.014) and IL4 and TNFα remain negatively (HR = 2.753, p = 0.002) and positively (HR = 0.224, p = 0.049) associated with DFS, respectively (Table 3).

Table 3.

Multivariate analysis of factors influencing OS and DFS in patients with resectable pancreatic cancer.

| 95% CI |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | HR | Lower | Upper | p |

| OS | ||||

| Tumor grade G3 | 3.698 | 1.602 | 8.535 | 0.002 |

| IP10 | 3.097 | 1.257 | 7.632 | 0.014 |

| DFS | ||||

| Tumor grade G3 | 2.472 | 1.339 | 4.564 | 0.004 |

| Adjuvant therapy | 0.609 | 0.312 | 1.186 | 0.145 |

| IL4 | 2.753 | 1.465 | 5.175 | 0.002 |

| TNFα | 0.224 | 0.051 | 0.995 | 0.049 |

| INFγ | 0.864 | 0.195 | 3.833 | 0.847 |

HR, hazard ratio; CI, confidential interval.

Since the multivariate analysis revealed both IL4 and TNFα as independent predictors of DFS, we tried to determine whether the two factors could interact to affect the prognosis of patients. Indeed, concurrent plasma concentrations of IL4 and TNFα lower and higher than their respective cutoffs, identified patients with best prognosis (HR = 0.313, p < 0.0001) (Fig. 3A).

Discussion

To our knowledge, this study represents the most comprehensive profiling of cytokines in the largest prospective cohort of resectable PDAC patients to date. We demonstrated that IL4 is the most significant independent prognostic factor for DFS in resectable PDAC patients among a series of cytokines, representing a potential biomarker to stratify patients suited for surgery from patients with high risk of early recurrence who may avoid unnecessary resections.

TH2 immune response is defined by the cytokines IL4, IL5, IL9, and IL13, which induce in turn a complex inflammatory response characterized by TH2 subset of CD4+ helper T cells, eosinophils, mast cells, basophils, and alternatively activated macrophages. In particular, IL4 is the signature cytokine of the TH2 effector cells, by acting as both an inducer and an effector cytokine of these cells.15

In most solid tumors, it is generally conceived that a TH2 inflammation promotes tumorigenesis and tumor growth. In particular, several studies provided evidence for a general TH2 shift in PDAC with a predominance of TH2 cytokines in the plasma of patients (reviewed in16). Important studies mainly by the group of Protti and colleagues17 provided evidence on the mechanisms underlying these observations. They identified a cross talk between PDAC cells and microenvironment components, resulting in thymic stromal lymphopoietin production by activated cancer-associated fibroblasts that, in turn, induced a TH2 cell polarization through myeloid dendritic cell conditioning. The TH2 (GATA-3+)/TH1 (T-bet+) lymphoid cells ratio was independently predictive of DFS and OS in a population of resected PDAC patients. More recently, they demonstrated that basophils recruited in tumor-draining lymph nodes of PDAC patients regulate tumor promoting TH2 inflammation, being the early source of IL4 necessary for the full stabilization of the TH2 phenotype.18 Our study contributes to this field by providing evidence, through an inductive approach, for a TH2 shift in those PDAC patients for which we expect an early recurrence of disease. We examined a comprehensive immune circulating biomarkers panel demonstrating that high pre-surgical plasma levels of the TH2 cytokines IL4, IL5, IL6, and low plasma levels of TH1 cytokines TNFα and INFγ were significantly associated with worst patients' outcome. More importantly, in the multivariate analysis, we confirmed IL4 as the strongest independent prognostic factor for DFS, a clinical end point directly correlated with tumor aggressiveness that could be not corrupted by the effect of subsequent lines of therapy.

IL4 was identified as the original inducer of the polarization of the alternatively activated M2 macrophages,19 which are generally conceived to suppress antitumor immunity and to favor growth and spreading in solid tumors.20 However, recent studies correlating the infiltration of M2-polarized CD163+ macrophages and prognosis in patients affected by resectable PDAC reached opposite conclusions.21,22 In this regard, our study demonstrated that high plasma levels of the cytokines involved in macrophage recruitment MIP1α, GM-CSF, and MCP1 were significantly associated with shorter patients' survival after surgery.

Beside TH2 inflammatory cells, a FOXP3+ regulatory T cells (Treg) enriched pancreatic tumor infiltrate has been found to correlate with shorter patient survival.23,24 This cell subtype can be recruited in the tumor microenvironment by the chemokine IP10 expressed by pancreatic stellate cells, leading to immunosuppressive and tumor-promoting effects.25,26 Consistently with these observations, we demonstrated that high IP10 plasma level were negatively associated with patients' OS.

In conclusion, our present study prospectively demonstrated through an inductive approach that circulating markers of a TH2 immune response, and macrophages and Treg recruitment could be predictive of early metastatic relapse and poor prognosis in resectable PDAC patients. The simple measurement of these cytokines by a non-invasive, blood-based assay, and the interpretation of their significance based on the cutoff thresholds here determined could represent a significant advantage over the assessment of the immune cells infiltration and differentiation in preoperative tumor biopsies, which often provide insufficient material to generate intratumor immune profiles and could not completely recapitulate the heterogeneity of these tumors. IL4 emerged among several other cytokines as the most significant independent prognostic factor for DFS in resectable PDAC patients. The expression of this TH2 cytokine could be useful to select patients with high risk of early recurrence who may avoid an unnecessary resection.

Patients and methods

Patients

Inclusion criteria for this study were histopathological confirmation of PDAC, no prior neo-adjuvant therapy, no evidence of metastatic disease, eligible for surgical resection. Peripheral blood samples were prospectively collected from all patients before surgical resection using EDTA-containing tubes. Plasma was isolated from each sample by centrifugation and stored at −20°C. The variables evaluated included age, gender, tumor location, tumor size, differentiation status, lymph node involvement and TNM stage,27 patterns of resection margins, patterns of recurrence. DFS was determined from the time of surgery until local or metastatic PDAC tumor recurrence. OS was defined as the time of surgery to death. Informed consent was obtained from all subjects. This study was performed in accordance with the ethical standards of the Helsinki Declaration of the World Medical Association.

Multiplex cytokines profiling

Using a 23-plex kit from Bio-Rad, all plasma specimens were analyzed for interleukin (IL)1β, IL2, IL4, IL5, IL6, IL7, IL8 (CXCL8), IL9, IL-12p70, IL13, IL15, IL17a, eotaxin (CCL−11), IL1Rα, granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF), granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF), IFNγ, IP10 (CXCL10), monocyte chemoattractant protein (MCP1; CCL2), macrophage inflammatory protein 1α (MIP1α; CCL3), MIP1β (CCL4), TNFα, and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF). All Luminex assays were performed according to the instructions provided by the manufacturer (Bio-Rad Laboratories). All Luminex assays were performed according to the instructions provided by the manufacturer (Bio-Rad Laboratories). Median fluorescence intensities were collected on a Luminex-200 instrument, using Bio-Plex Manager software version 6.2. Standard curves for each cytokine were generated using the premixed lyophilized standards provided in the kits.

Cytokine concentrations in samples were determined from the standard curve using a 5-point regression to transform mean fluorescence intensities into concentrations.

Statistical analysis

Survival curves were drawn by Kaplan–Meier estimates and compared by log rank test. Univariate and multivariate analyses of DFS and OS, with stepwise variable selection, were conducted by Cox's proportional hazard regression models. Multivariate analysis was conducted using the clinical-pathologic variables with a p-value < 0.05 and the strongest significant molecular variables in univariate analysis (p-value < 0.01). The optimal cutoff thresholds for soluble biomarkers were obtained based on the maximization of the Youden's statistics J = sensitivity+specificity+128 using an R-based software as described in Budczies et al.29 Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 24.0 statistical software (SPSS, Inc.), GraphPad Prism software program (version 6.0; GraphPad Software), and the statistical language R.

Supplementary Material

Disclosure of potential conflicts of interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

Acknowledgments

Part of the work was performed at the Laboratorio Universitario di Ricerca Medica (LURM) Research Center, University of Verona.

Funding

This work was supported by the Associazione Italiana per la Ricerca sul Cancro (AIRC) under Investigator Grant (IG) n°19111 to DM, IG n°18599 to GT, and 5 per mille Grant n°12182 to AS. Partial support was also provided by the Basic Research Project 2015 through the University of Verona, and by the Nastro Viola patients' association donations to DM.

References

- 1.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2015. CA Cancer J Clin 2015; 65:5-29; PMID:25559415; https://doi.org/ 10.3322/caac.21254 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rahib L, Smith BD, Aizenberg R, Rosenzweig AB, Fleshman JM, Matrisian LM. Projecting cancer incidence and deaths to 2030: the unexpected burden of thyroid, liver, and pancreas cancers in the United States. Cancer Res 2014; 74:2913-21; PMID:24840647; https://doi.org/ 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-14-0155 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Neoptolemos JP, Stocken DD, Bassi C, Ghaneh P, Cunningham D, Goldstein D, Padbury R, Moore MJ, Gallinger S, Mariette C et al.. Adjuvant chemotherapy with fluorouracil plus folinic acid vs gemcitabine following pancreatic cancer resection: a randomized controlled trial. Jama 2010; 304:1073-81; PMID:20823433; https://doi.org/ 10.1001/jama.2010.1275 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Melisi D, Calvetti L, Frizziero M, Tortora G. Pancreatic cancer: systemic combination therapies for a heterogeneous disease. Curr Pharmaceutical Design 2014; 20:6660-9; PMID:25341938; https://doi.org/ 10.2174/1381612820666140826154327 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Giraldo NA, Becht E, Remark R, Damotte D, Sautes-Fridman C, Fridman WH. The immune contexture of primary and metastatic human tumours. Curr Opin Immunol 2014; 27:8-15; PMID:24487185; https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.coi.2014.01.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Grivennikov SI, Greten FR, Karin M. Immunity, inflammation, and cancer. Cell 2010; 140:883-99; PMID:20303878; https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.cell.2010.01.025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Quail DF, Joyce JA. Microenvironmental regulation of tumor progression and metastasis. Nat Med 2013; 19:1423-37; PMID:24202395; https://doi.org/ 10.1038/nm.3394 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fridman WH, Pages F, Sautes-Fridman C, Galon J. The immune contexture in human tumours: impact on clinical outcome. Nat Rev Cancer 2012; 12:298-306; PMID:22419253; https://doi.org/ 10.1038/nrc3245 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sideras K, Braat H, Kwekkeboom J, van Eijck CH, Peppelenbosch MP, Sleijfer S, Bruno M. Role of the immune system in pancreatic cancer progression and immune modulating treatment strategies. Cancer Treat Rev 2014; 40:513-22; PMID:24315741; https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.ctrv.2013.11.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Roshani R, McCarthy F, Hagemann T. Inflammatory cytokines in human pancreatic cancer. Cancer Lett 2014; 345:157-63; PMID:23879960; https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.canlet.2013.07.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ebrahimi B, Tucker SL, Li D, Abbruzzese JL, Kurzrock R. Cytokines in pancreatic carcinoma: correlation with phenotypic characteristics and prognosis. Cancer 2004; 101:2727-36; PMID:15526319; https://doi.org/ 10.1002/cncr.20672 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mitsunaga S, Ikeda M, Shimizu S, Ohno I, Furuse J, Inagaki M, Higashi S, Kato H, Terao K, Ochiai A. Serum levels of IL-6 and IL-1beta can predict the efficacy of gemcitabine in patients with advanced pancreatic cancer. Br J Cancer 2013; 108:2063-9; PMID:23591198; https://doi.org/ 10.1038/bjc.2013.174 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bellone G, Smirne C, Mauri FA, Tonel E, Carbone A, Buffolino A, Dughera L, Robecchi A, Pirisi M, Emanuelli G. Cytokine expression profile in human pancreatic carcinoma cells and in surgical specimens: implications for survival. Cancer Immunol Immunother 2006; 55:684-98; PMID:16094523; https://doi.org/ 10.1007/s00262-005-0047-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Farren MR, Mace TA, Geyer S, Mikhail S, Wu C, Ciombor K, Tahiri S, Ahn D, Noonan AM, Villalona-Calero M et al.. Systemic immune activity predicts overall survival in treatment-naive patients with metastatic pancreatic cancer. Clin Cancer Res 2016; 22:2565-74; PMID:26719427; https://doi.org/ 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-15-1732 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wynn TA. Type 2 cytokines: mechanisms and therapeutic strategies. Nat Rev Immunol 2015; 15:271-82; PMID:25882242; https://doi.org/ 10.1038/nri3831 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wormann SM, Diakopoulos KN, Lesina M, Algul H. The immune network in pancreatic cancer development and progression. Oncogene 2014; 33:2956-67; PMID:23851493; https://doi.org/ 10.1038/onc.2013.257 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.De Monte L, Reni M, Tassi E, Clavenna D, Papa I, Recalde H, Braga M, Di Carlo V, Doglioni C, Protti MP et al.. Intratumor T helper type 2 cell infiltrate correlates with cancer-associated fibroblast thymic stromal lymphopoietin production and reduced survival in pancreatic cancer. J Exp Med 2011; 208:469-78; PMID:21339327; https://doi.org/ 10.1084/jem.20101876 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.De Monte L, Wormann S, Brunetto E, Heltai S, Magliacane G, Reni M, Paganoni AM, Recalde H, Mondino A, Falconi M et al.. Basophil recruitment into tumor-draining lymph nodes correlates with Th2 inflammation and reduced survival in pancreatic cancer patients. Cancer Res 2016; 76:1792-803; PMID:26873846; https://doi.org/ 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-15-1801-T [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stein M, Keshav S, Harris N, Gordon S. Interleukin 4 potently enhances murine macrophage mannose receptor activity: a marker of alternative immunologic macrophage activation. J Exp Med 1992; 176:287-92; PMID:1613462; https://doi.org/ 10.1084/jem.176.1.287 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Biswas SK, Mantovani A. Macrophage plasticity and interaction with lymphocyte subsets: cancer as a paradigm. Nat Immunol 2010; 11:889-96; PMID:20856220; https://doi.org/ 10.1038/ni.1937 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tjomsland V, Niklasson L, Sandstrom P, Borch K, Druid H, Bratthall C, Messmer D, Larsson M, Spångeus A. The desmoplastic stroma plays an essential role in the accumulation and modulation of infiltrated immune cells in pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Clin Dev Immunol 2011; 2011:212810; PMID:2190968; https://doi.org/ 10.1155/2011/212810 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kurahara H, Shinchi H, Mataki Y, Maemura K, Noma H, Kubo F, Sakoda M, Ueno S, Natsugoe S, Takao S. Significance of M2-polarized tumor-associated macrophage in pancreatic cancer. J Surgical Res 2011; 167:e211-9; PMID:19765725; https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.jss.2009.05.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hiraoka N, Onozato K, Kosuge T, Hirohashi S. Prevalence of FOXP3+ regulatory T cells increases during the progression of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma and its premalignant lesions. Clin Cancer Res 2006; 12:5423-34; PMID:17000676; https://doi.org/ 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-0369 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yamamoto T, Yanagimoto H, Satoi S, Toyokawa H, Hirooka S, Yamaki S, Yui R, Yamao J, Kim S, Kwon AH. Circulating CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells in patients with pancreatic cancer. Pancreas 2012; 41:409-15; PMID:22158072; https://doi.org/ 10.1097/MPA.0b013e3182373a66 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lunardi S, Jamieson NB, Lim SY, Griffiths KL, Carvalho-Gaspar M, Al-Assar O, Yameen S, Carter RC, McKay CJ, Spoletini G, et al.. IP-10/CXCL10 induction in human pancreatic cancer stroma influences lymphocytes recruitment and correlates with poor survival. Oncotarget 2014; 5:11064-80; PMID:25415223; https://doi.org/ 10.18632/oncotarget.2519 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lunardi S, Lim SY, Muschel RJ, Brunner TB. IP-10/CXCL10 attracts regulatory T cells: implication for pancreatic cancer. Oncoimmunology 2015; 4:e1027473; PMID:26405599; https://doi.org/ 10.1080/2162402X.2015.1027473 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sobin LH, Compton CC. TNM seventh edition: what's new, what's changed: communication from the International Union against cancer and the american joint committee on cancer. Cancer 2010; 116:5336-9; PMID:20665503; https://doi.org/ 10.1002/cncr.25537 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Youden WJ. Index for rating diagnostic tests. Cancer 1950; 3:32-5; PMID:15405679; https://doi.org/ [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Budczies J, Klauschen F, Sinn BV, Gyorffy B, Schmitt WD, Darb-Esfahani S, Denkert C. Cutoff finder: a comprehensive and straightforward Web application enabling rapid biomarker cutoff optimization. PloS One 2012; 7:e51862; PMID:23251644; https://doi.org/ 10.1371/journal.pone.0051862 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.