ABSTRACT

Cancer immunotherapy is one of the most promising and benign therapies against metastatic cancer. However, most cancer patients are old and elderly react less efficient to cancer vaccines than young adults, due to T cell unresponsiveness. Here we present data of cancer vaccination in young and old mice with metastatic breast cancer (4T1 model). We tested adaptive and innate immune responses to foreign antigens (Listeria-derived) and self-antigens (tumor-associated antigens (TAA)) and their contribution to elimination of metastases at young and old age. Three different protocols were tested with Listeria: a semi- and exclusive-therapeutic protocol both one-week apart, and an exclusive therapeutic protocol frequently administered. Adaptive and innate immune responses were measured by ELISPOT in correlation with efficacy in the 4T1 model. We found that Listeria induced immunogenic tumor cell death, resulting in CD8 T cell responses to multiple TAA expressed by the 4T1 tumors. Only exclusive therapeutic frequent immunizations were able to overcome immune suppression and to activate TAA- and Listeria-specific CD8 T cells, in correlation with a strong reduction in metastases at both ages. However, MHC class Ia antibodies showed inhibition of CD8 T cell responses to TAA at young but not at old age, and CD8 T cell depletions in vivo demonstrated that the T cells contributed to reduction in metastases at young age only. These results indicate that CD8 T cells activated by Listeria has an antitumor effect at young but not at old age, and that metastases at old age have been eliminated through different mechanism(s).

KEYWORDS: Breast cancer, immune senescence, immune suppression, listeria monocytogenes, metastases

Abbreviations

- ANOVA

analysis of variance

- CD

cluster differentiation

- CFU

colony forming unit

- CMV

cytomegalovirus

- CTL

cytotoxic T lymphocytes

- ELISPOT

enzyme-linked immunospot assay

- ET-frequently

exclusive therapeutic immunizations administered frequently

- ET-weekly

exclusive therapeutic immunizations administered weekly

- GM-CSF

granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor

- HRPN

horseradish peroxidase N

- IFN

interferon

- IL

interleukin

- Ip

intraperitoneally

- LD

lethal dosis

- LLO

listeriolysin O

- Mage

melanoma-associated antigen

- M

months

- MDSC

myeloid-derived suppressor cells

- MHC

major histocompatibility complex

- NK

natural killer

- ROS

reactive oxygen species

- ST-weekly

semi-therapeutic immunizations administered weekly

- TAA

tumor-associated antigens

- TME

tumor microenvironment

- Tregs

regulatory T cells

Introduction

While conventional therapies such as surgery followed by chemotherapy or radiation are quite successful against primary tumors, for metastases there is no cure. Immunotherapy may be the most promising and benign option for curing metastatic cancer because T cells can be selectively activated to patient's own tumor and metastases, without harming normal cells. However, most cancer patients are old and elderly react less efficient to vaccines than young adults, due to T cell unresponsiveness.1-3 Various causes have been described for T-cell unresponsiveness at old age in mice and humans, such as lack of naive T cells, lack of CD28 expression on T cells, deficiency in the upregulation of co-stimulatory molecules on aged dendritic cells (DCs), reduction in the T cell repertoire, among other age-related impairments.4-9 T cell unresponsiveness has also been found in cancer vaccination at older age but this is far less well studied. Increased numbers of myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSC) in the tumor microenvironment (TME), increased numbers of Tregs, lower cytolytic activity toward tumors, and lower production of interferon (IFN)γ by CD8 T cells has been found in old compared with young mice with cancer.10-16 Since the big breakthrough with checkpoint inhibitors in cancer vaccination in 201317 we can expect a strong rise in cancer immunotherapeutic approaches in the near future. Therefore, tailoring cancer immunotherapy to older age should be a next step forward to improve cancer management. While only a few studies have been reported about cancer vaccination at older age (for a review see Gravekamp18), more research is needed to get a deeper understanding of the problems we may face in cancer immunotherapy of the elderly.

Our laboratory has developed Listeria-based cancer immunotherapy for metastatic breast cancer.15,19 We have shown that attenuated Listeria monocytogenes infects myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSC), which are present in large numbers in blood of mice and patients with cancer.20,21 These MDSC deliver Listeria selectively to tumor cells,15,22 because MDSC are selectively attracted by the tumor cells through chemoattractants and cytokines.23 Once at the tumor site Listeria spreads from MDSC into tumor cells15,22,24 through a mechanism specific for Listeria,25 and then kills tumor cells through Listeria-induced ROS, and through Listeria-specific T cells.26 Listeria also infects tumor cells directly through receptor-ligand interactions (for a review see Gravekamp and Paterson, 201027).

In the study presented here, we tested Listeria-based immunotherapy in young (3 months; comparable to humans of 12.6 years) and old (18 months; comparable to humans of 75.9 y old) mice with metastatic breast cancer (4T1 model), and analyzed innate and adaptive immune responses to foreign antigens (Listeria) and self-antigens (tumor-associated antigens), and their role in elimination of tumors and metastases in vivo. Three immunization protocols were tested: semi therapeutic weekly (ST-weekly), exclusive therapeutic weekly (ET-weekly) ET-Weekly, and exclusive therapeutic every other day (ET-frequently) (for a detailed overview see Fig. 1). We found a remarkable result, i.e. immunizations with Listeria generated CD8 T cells not only to Listeria antigens but also to various TAA expressed by the 4T1 tumors and metastases such as Mage-b and Survivin28,29 at both ages, indicating that Listeria-generated ROS induced immunogenic tumor cell death. ROS is known for inducing immunogenic tumor cell death.30,31 We also found that CD8 T cell responses to foreign antigens like Listeria antigens were less affected by aging than the CD8 T cells to self-TAA. Also innate immune responses were less affected by aging than the adaptive T cell responses. Therapeutically, the best results were obtained with the ET-Frequently immunization protocol. This treatment modality activated the innate and adaptive immune responses and strongly reduced the number of metastases at both ages. However, more detailed analysis with CD8 T cell depletions in vivo revealed that they contributed to the elimination of metastases in young mice only. In support of these results, anti-MHC class Ia antibodies showed inhibition of CD8 T cell responses to TAA Survivin and Mage-b at young age only. This study indicates that Listeria-activated CD8 T cells are not involved in antitumor responses at old age, but that other mechanism(s) have contributed to the reduction in metastases at old age.

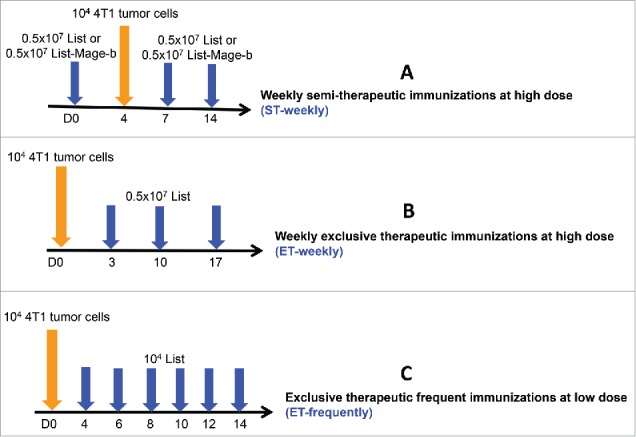

Figure 1.

Schematic overview of all immunization protocols with Listeria. Three different immunization strategies were tested in young (3 months (m)) and old (18 m) mice with metastatic breast cancer (4T1 model) and their innate and adaptive immune responses were analyzed in relation to efficacy (effect on metastases and tumor). The first strategy included semi-therapeutic immunizations (one before and 2 after tumor development), administered once a week with high doses of Listeria or Listeria-Mage-b (as indicated in the text) (ST-weekly)(A). The second immunization strategy was exclusively therapeutic (3 times after tumor development), once a week with high doses of Listeria (ET-weekly)(B). The third strategy consisted of multiple exclusively therapeutic immunizations (6 times after tumor development), every other day with low doses of Listeria (ET-frequently)(C).

Results

ST-weekly immunizations with Listeria-Mage-b activate CD8 T cells to Mage-b at young age only but innate and adaptive immune responses to Listeria at young and old age

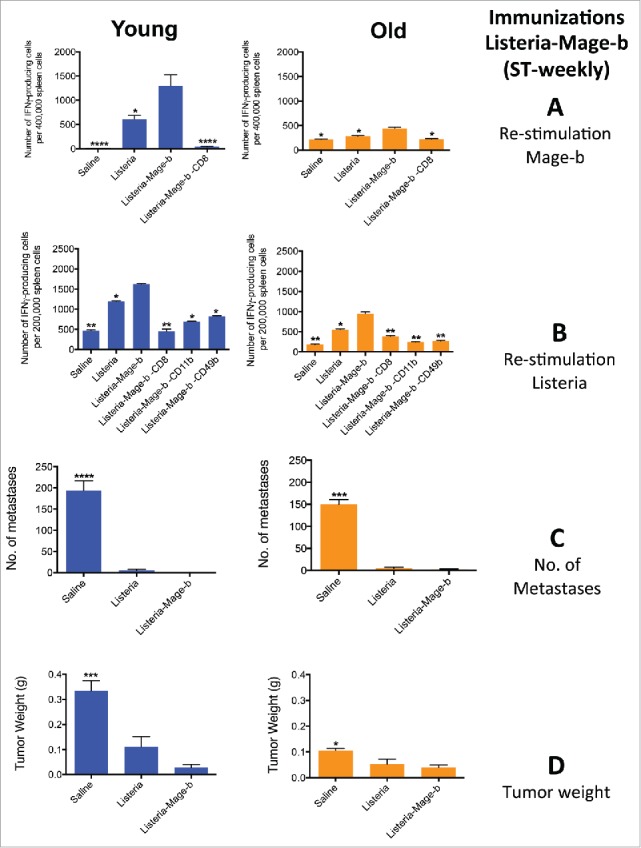

Based on a previous study with DNA vaccine pcDNA3.1-Mage-b, demonstrating that CD8 T cell responses could be induced to TAA Mage-b at young but not at old age,10 we now tested whether Listeria-Mage-b could overcome immune senescence. Young (3 months) and old (18 months) BALB/c mice were immunized with Listeria-Mage-b using a semi-therapeutic immunization protocol (once before and twice after tumor challenge), one-week apart (ST-weekly) (Fig. 1A) and analyzed adaptive and innate immune responses to TAA and Listeria by ELISPOT. Here we demonstrate that ST-weekly immunizations with Listeria-Mage-b activated CD8 T cell responses to Mage-b at young but poorly at old age (Fig. 2A). Interestingly, CD8 T cell responses could be induced to Listeria at both ages, although this was somewhat diminished at old age (Fig. 2B). Moreover, innate immune responses to Listeria like macrophages (CD11b+ cells) and NK (CD49b+ cells) were strongly activated to Listeria at young and old age (Fig. 2B). Also here the innate immune responses were somewhat diminished at old compared with young age.

Figure 2.

ST-weekly immunizations with Listeria-Mage-b activate CD8 T cells to Mage-b at young age only but innate and adaptive immune responses to Listeria at young and old age. Young (3 m) and old (18 m) BALB/c mice were immunized with Listeria as described in Fig. 1A (ST-weekly). Two days after the last immunization, these young and old mice were analyzed for immune responses to Mage-b (A) and Listeria (B), and for the frequency of metastases (C), and tumor weight (D). Splenocytes were isolated from tumor-bearing young and old mice, pooled in each group, re-stimulated with pcDNA3.1-Mage-b or Listeria, and analyzed for the number of IFNγ-producing CD8 T cells, NK (CD49b+) cells and macrophages (CD11b+) by ELISPOT. CD8 T cells, NK cells, and macrophages were depleted by magnetic beads technique. The number of IFNγ-producing spots was determined per 200,000 splenocytes. n = 5 mice per group. This experiment was performed 3 times and the results were averaged. ELISPOT data was statistically analyzed by the Unpaired t-test, and efficacy data by the Mann-Whitney test. In both studies, all groups were compared with Listeria. *p < 0.05, **<0.01, ***<0.001,****<0.0001 is significant. The error bars represent the SEM.

In previous studies we found that Listeria-Mage-b and Listeria were equally effective against metastases and tumors at young age (old age was not tested), indicating that Listeria itself contributed to the reduction in metastases and tumors.26 Moreover, we demonstrated that depletion of CD8 T cells in vivo using anti-CD8 antibodies resulted in regrowth of primary tumors in young mice that received Listeria only compared with the saline and isotype control groups, indicating that CD8 T cell responses generated by Listeria contributed to tumor reduction in vivo.26 Here we found that Listeria-Mage-b and Listeria were equally effective against the metastatic breast cancer at both young and old age (Fig 2C and D). Therefore, the next immunizations were performed with Listeria only in young and old mice.

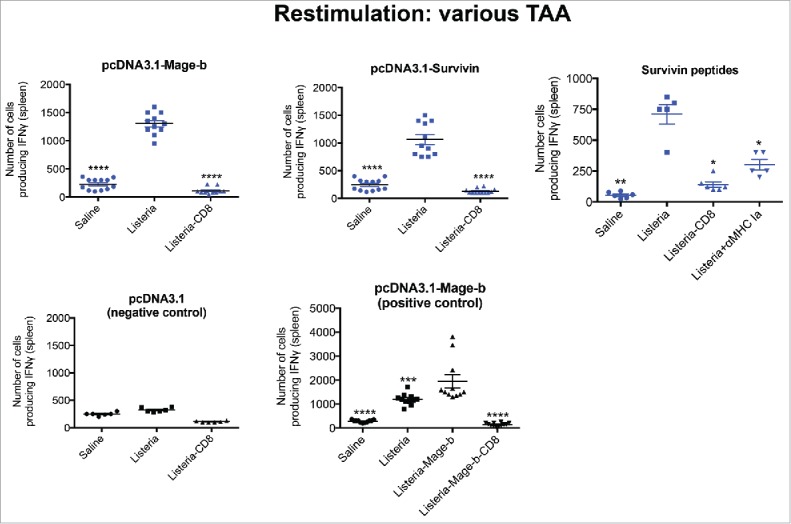

ST-weekly immunizations with Listeria activate CD8 T cell responses to multiple TAA, most likely through Listeria-induced immunogenic tumor cell death

An obvious result was that ST-weekly immunizations with Listeria alone generated CD8 T cell responses to TAA Mage-b while Mage was not expressed by Listeria. Since Listeria kills tumor cells through ROS, and ROS induces immunogenic tumor cell death,30,31 it is likely that Listeria-induced ROS-mediated tumor cell death, resulted in CD8 T cell responses to Mage-b. We decided to test this in more detail by ELISPOT. Again BALB/c mice (3 months) were immunized (ST-weekly) with Listeria but now we tested CD8 T cell responses to several TAA such as Mage-b, and Survivin (both antigens are expressed by 4T1 tumors and metastases),19,28,32 aiming at cross presentation of TAA by Listeria-killed tumor cells. As shown in Fig. 3, CD8 T cell responses were observed against both TAAs expressed by the metastases and tumors of the 4T1 model. To demonstrate MHC class I-restricted T cell responses to Survivin, restimulation with Survivin66–74 peptide (GWEPDDNPI) matching the H2-d haplotype was performed in the presence and absence of anti-MHC class Ia antibodies. As negative control we restimulated with pcDNA3.1, and as positive control we immunized with Listeria-Mage-b (Fig. 3). Strong CD8 T cell responses were observed to the Survivin peptides in the Listeria-treated group, and the MHC class Ia antibodies showed a strong decrease in the number of spleen cells producing IFNγ (Fig. 3), indicating the presence of MHC class I-restricted CD8 T cell responses to Survivin.

Figure 3.

ST-weekly immunizations once a week with Listeria generated CD8 T cell responses to multiple TAA expressed by 4T1 tumor cells. Young (3 m) BALB/c mice were immunized with Listeria only as described in Fig. 1A (ST-weekly) in the 4T1 model. Two days after the last immunization, mice were killed and analyzed for immune responses to various TAA in the spleen. Briefly, spleen cells of treated and control mice were transfected with pcDNA3.1-Mage-b or pcDNA3.1-Survivin. pcDNA3.1 was included as a negative and immunizations with Listeria-Mage-b as a positive control. After 72hrs, spleen cells ± CD8 depletion were analyzed for the number of IFNγ-producing CD8 T cells by ELISPOT. To demonstrate MHC class I-restricted T cell responses to Survivin, restimulation with Survivin66–74 peptide (GWEPDDNPI) matching the H2-d haplotype was performed in the presence and absence of anti-MHC class Ia antibodies. n = 5 mice per group. This experiment was performed 3 times and results were averaged. ELISPOT data was statistically analyzed by the Unpaired t-test. All groups were compared with Listeria, with an exception for the graph with the pos control (here all groups were compared with Listeria-Mage-b). *p < 0.05, **<0.01,***<0.001 ****<0.0001 is significant. The error bars represent the SEM.

ST-weekly immunizations with Listeria alone induce CD8 T cell responses to Mage-b at young age only but innate and adaptive immune responses to Listeria at young and old age

Here we repeated the ST-weekly immunizations with Listeria alone but now at young and old age. Again, CD8 T cell responses to Mage-b could be generated at young age only (Fig. 4A). However, CD8 T cell responses as well as innate immune responses such as NK and macrophages to Listeria were high at young and old age (Fig. 4B). This correlated again with a dramatic effect on the metastases and tumors at young and old age (Fig. 4CD). These results demonstrated that Listeria was able to activate CD8 T cell responses to TAA at young but not at old age, while innate immune responses were highly activated at both ages. This raised the question whether the innate immune responses could be used to help adaptive immune responses at old age. Another issue raised here is that the ST-Weekly immunization protocol was of less relevance for clinical trials. Therefore, we designed new exclusive therapeutic immunization strategies.

Figure 4.

ST-weekly immunizations with Listeria alone induce CD8 T cell responses to Mage-b at young age only but innate and adaptive immune responses to Listeria at young and old age. Young (3 m) and old (18 m) BALB/c mice were immunized with Listeria or controls as described in Fig. 1A (ST-weekly). Two days after the last immunization, these young and old mice were analyzed for immune responses to Mage-b (A) and Listeria (B), and for the frequency of metastases (C) and tumor weight (D). Splenocytes were isolated from tumor-bearing young and old mice, pooled in each group, re-stimulated with pcDNA3.1-Mage-b or Listeria, and analyzed for the number of IFNγ-producing CD8 T cells, NK (CD49b+.) cells and macrophages (CD11b+) by ELISPOT. CD8 T cells, NK cells, and macrophages were depleted by magnetic beads technique. The number of IFNγ-producing spots was determined per 200,000 splenocytes. n = 5 mice per group. This experiment was performed 3 times and the results were averaged. ELISPOT data was statistically analyzed by the Unpaired t-test, and efficacy data by the Mann-Whitney test. In both studies, all groups were compared with Listeria. **p < 0.01, ***<0.001, ****<0.0001 is significant. The error bars represent the SEM.

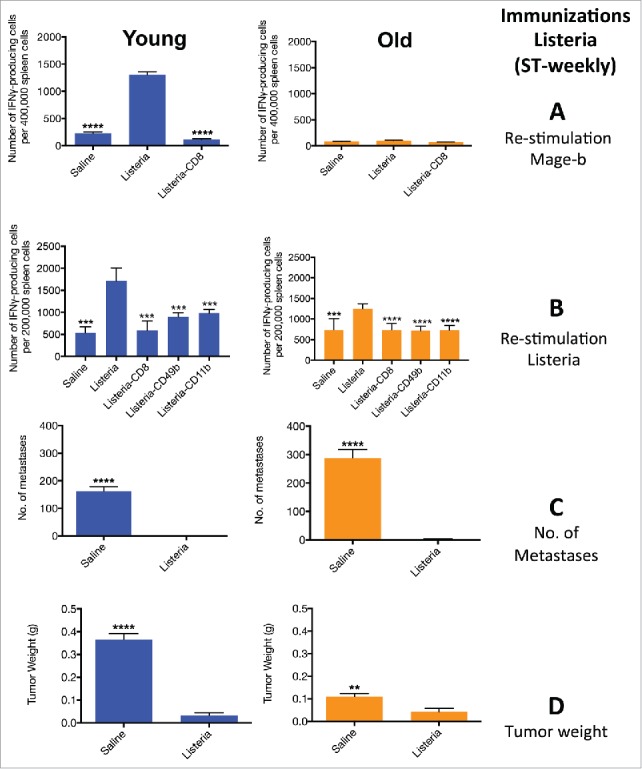

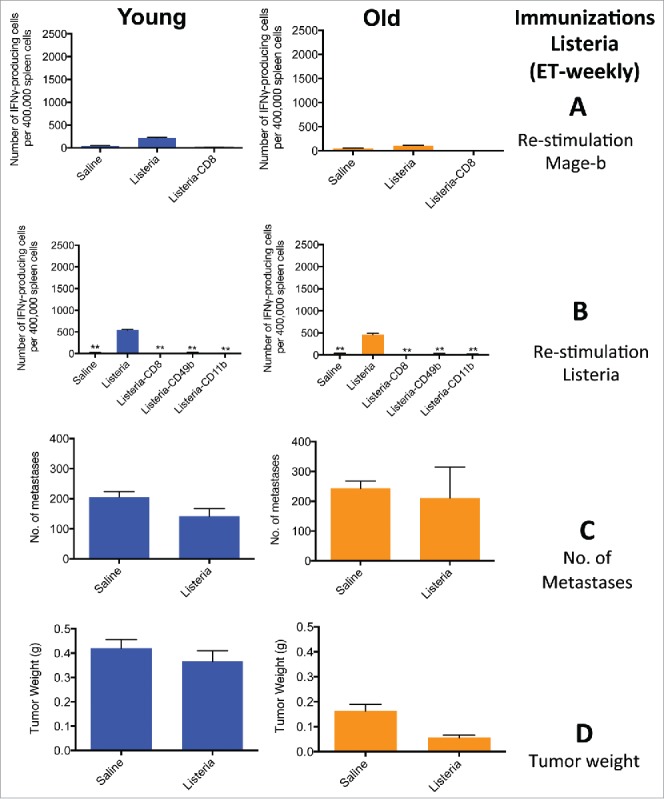

ET-weekly immunizations with Listeria induce poor CD8 T cell responses to Mage-b and poor innate and adaptive immune responses to Listeria at young and old age

The following experiments show that exclusive therapeutic (ET-weekly) immunizations one week apart with Listeria were completely overwhelmed by immune suppression in the tumor microenvironment (TME), in contrast to the ST-weekly immunizations because in this latter protocol the first immunization was administered before tumor challenge when immune suppression was absent. Briefly, BALB/c mice were first challenged with 4T1 tumor cells, and then 3 times immunized with Listeria once a week. The innate immune responses were weak, and the adaptive immune responses could hardly be detected at old age and even at young age (Fig. 5A and B). Moreover, this correlated with poor efficacy, i.e., growth of metastases and tumors were reduced by 20–30% only or not at all at young and old age (Fig. 5C and D). These results demonstrate that immune suppression occurs at young and old age. We concluded that to overcome the age-related effect on CD8 T cell responses to TAA, we first needed to overcome immune suppression. Therefore, we used a recently developed immunization protocol consisting of multiple immunizations with Listeria every other day that was effective against metastases at young and old age but immune responses to TAA were not analyzed yet using this immunization protocol.15 The results were amazing and shown in the next section.

Figure 5.

ET-weekly immunizations induced poor innate and adaptive immune responses to Listeria and Mage-b at young and old age. Young (3 m) and old (18 m) BALB/c mice were immunized with Listeria or controls as described in Fig. 1B. Two days after the last immunization, these young and old mice were analyzed for immune responses to Mage-b (A) and Listeria (B), and the frequency of metastases (C) and tumor weight (D). Splenocytes were isolated from tumor-bearing young and old mice, pooled in each group, re-stimulated with pcDNA3.1-Mage-b or Listeria, and analyzed for the number of IFNγ-producing CD8 T cells, NK (CD49b+) cells and macrophages (CD11b+.) by ELISPOT. CD8 T cells, NK cells, and macrophages were depleted by magnetic beads technique. The number of IFNγ-producing spots was determined per 200,000 splenocytes. n = 5 mice per group. This experiment was performed one (old) or 3 times (young) and the results were averaged. ELISPOT data was statistically analyzed by the Unpaired t-test, and efficacy data by the Mann-Whitney test. In both studies, all groups were compared with Listeria. p** < 0.01, is significant. The error bars represent the SEM.

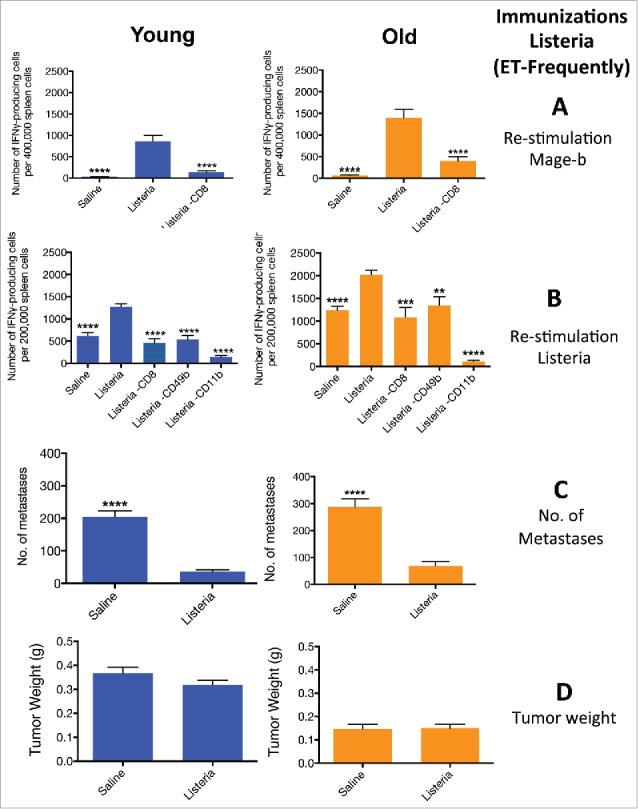

ET-frequently immunizations with Listeria induce strong CD8 T cell responses to Mage-b at young and old age and also strong innate and adaptive immune responses to Listeria at young and old age

Here we evaluated whether the strong therapeutic effect on metastases using ET-frequently immunization protocol correlated with CD8 T cell responses to Mage-b and/or Listeria in young and old mice with metastatic breast cancer. BALB/c mice were first challenged with 4T1 tumor cells, and then 6 times immunized with Listeria every other day. To prevent listeriosis we used a much lower dose of the Listeria (104 CFU) than in the semi-therapeutic immunizations (0.5 × 107 CFU) administered one week apart. For the first time we found strong CD8 T cell responses to Mage-b in a therapeutic setting (Fig. 6A). The effect of Listeria on innate immune responses was dramatic. Moreover, the total spleen cell population producing IFNγ was almost twice as high in old than in young tumor-bearing mice (Fig. 6B). Of note is that depletion of CD11b (macrophages) almost completely reduced the number of spleen cells producing IFNγ, while depletion of CD8 T cells and NK cells were significantly reduced by 40–50% compared with the non-depleted group (Fig. 6B). This correlated with a nearly complete elimination of the metastases at young and old age (Fig. 6C), while no effect was observed on the primary tumor (Fig. 6D).

Figure 6.

ET-frequently immunizations with Listeria induce strong CD8 T cell responses Mage-b at young and old age, and innate and adaptive immune responses to Listeria at young and old age. . Young (3 m) and old (18 m) BALB/c mice were immunized with Listeria or controls as described in Fig. 1C (ET-frequently). Two days after the last immunization, these young and old mice were analyzed for immune responses to Mage-b (A) and Listeria (B), and for the frequency of metastases (C) and tumor weight (D). Splenocytes were isolated from tumor-bearing young and old mice, pooled in each group, re-stimulated with Mage-b or Listeria, and analyzed for the number of IFNγ-producing CD8 T cells, NK (CD49b+) cells and macrophages (CD11b+) by ELISPOT. CD8+ T cells, NK cells, and macrophages were depleted by magnetic beads technique. The number of IFNγ-producing spots was determined per 200,000 splenocytes. n = 5 mice per group. This experiment was performed 3 times and the results were averaged. ELISPOT data was statistically analyzed by the Unpaired t-test, and efficacy data by the Mann-Whitney test. In both studies, all groups were compared with Listeria. ****p < 0.0001 is significant. The error bars represent the SEM.

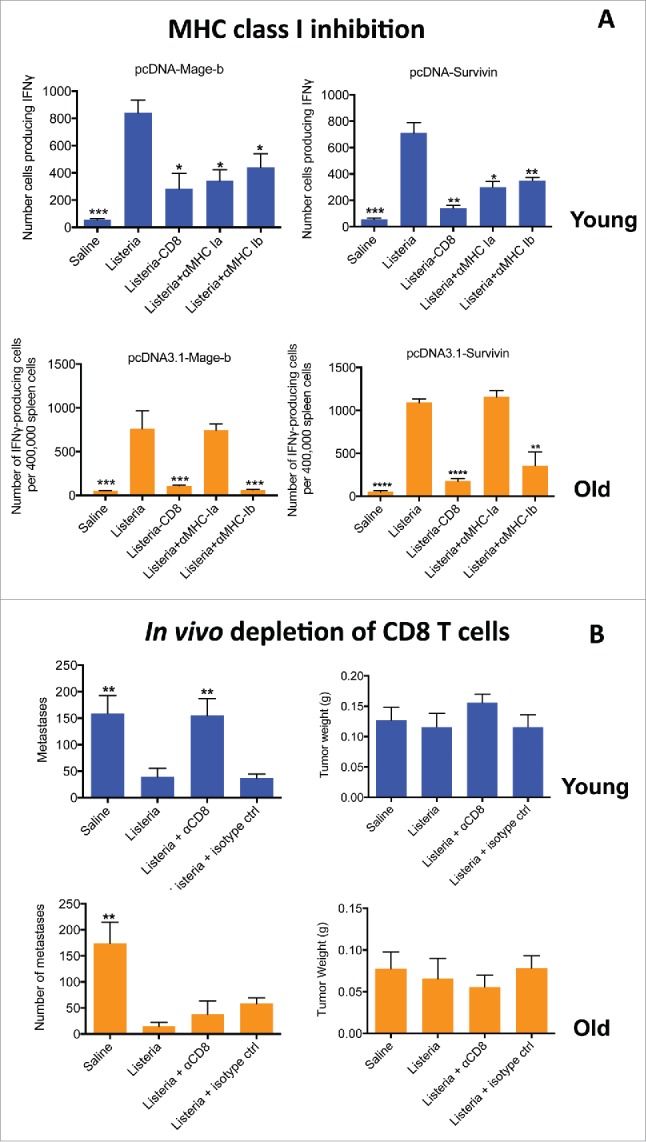

Anti-MHC class Ia antibodies inhibits TAA-restricted T cell responses at young but not at old age

To prove that CD8 T cell responses were generated to TAA in our assays, we repeated the ELISPOT in the presence and absence of MHC class Ia (classical class Ia) and Ib (non-conventional MHC class Ib) antibody using restimulation assays with Mage-b and Survivin plasmids. Both TAAs are highly expressed by the tumors of the 4T1 model.19,28,32 As shown here, the anti-MHC class Ia Abs strongly inhibited the CD8 T cell responses to Mage-b and Survivin at young but not at old age, while anti-MHC class Ib inhibited CD8 T cell responses to Mage-b and Survivin at both ages (Fig. 7A).

Figure 7.

Anti-MHC class Ia antibodies inhibited TAA-specific (T)cell responses at young but not at old age (A). Young (3 m) and old (18 m) BALB/c mice were immunized with Listeria or controls as described in Fig. 1C (ET-frequently). Two days after the last immunization, mice were killed and analyzed for immune responses to various TAA in the spleen. Briefly, spleen cells of treated and control mice were restimulated with pcDNA3.1-Mage-b or pcDNA3.1-Survivin, in the presence or absence of MHC class Ia or Ib antibodies. After 72hrs, spleen cells ± CD8 depletion were analyzed for the number of IFNγ-producing CD8 T cells by ELISPOT. n = 5 mice per group. This experiment was performed 3 times and results were averaged. All groups were compared with Listeria. Unpaired t-test. *p < 0.05, **<0.01, ***<0.001, ****<0.0001 is significant. The error bars represent the SEM. (B) Listeria-activated CD8 (T)cells contributed to reduction in metastases at young but not at old age in 4T1 model. CD8 T cells were depleted in 4T1-tumor-bearing young (3 m) and old (18 m) BALB/c mice with anti-CD8 antibodies (5 injections 3 d apart) concomitantly administered with the Listeria immunizations (6 injections). All mice were killed 2 d after the last anti-CD8 treatment, and analyzed for tumor weight and number of metastases. This experiment was performed 2 times with n = 7 mice per group. All groups were compared with Listeria. Mann-Whitney. p** < 0.01, is significant. The error bars represent the SEM.

Depletion of CD8 T cells in vivo demonstrates the contribution of CD8 T cells to reduction in metastases at young but not at old age

To analyze whether CD8 T cells contributed to the reduction in the metastases, we analyzed whether CD8 T cell depletions resulted in regrowth of the metastases in vivo. For this purpose, we challenged young and old BALB/c mice with 4T1 tumor cells and then alternately injected the mice 6 times with low dose Listeria (104 CFU) and 100 μg of anti-CD8 antibodies ip. As shown in Fig. 7B, CD8 T cells contributed to reduction in metastases at young but not at old age, indicating that the strong CD8 T cell responses contributed to reduction metastases at young but not at old age.

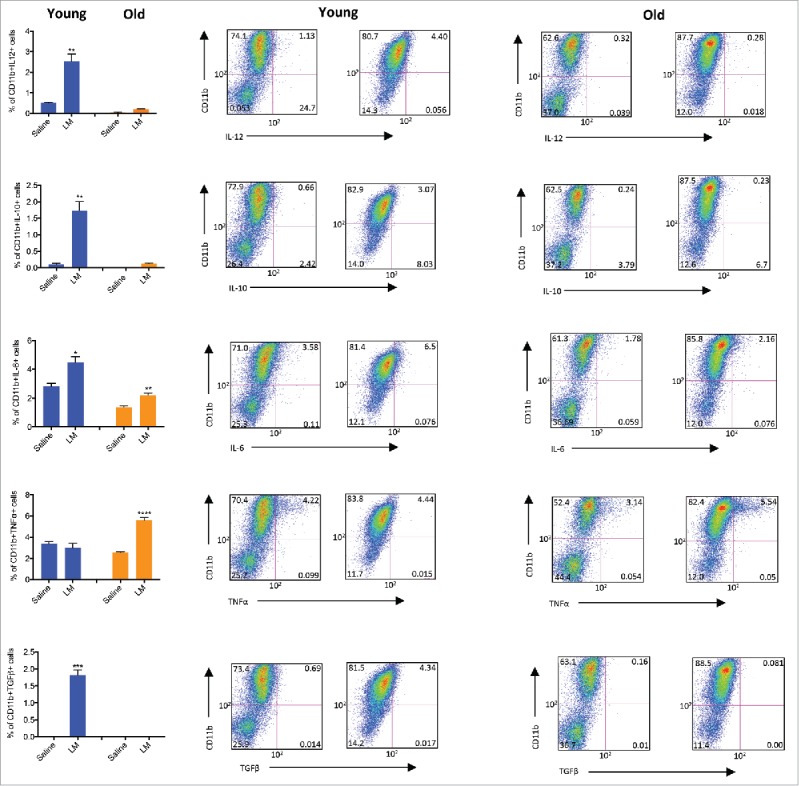

Listeria alters the function of CD11b+ cells in the metastases of mice at young and old age

As shown above (Fig 7B), CD8 T cells do contribute to the reduction in metastases at young but not at old age. Interestingly, we found that Listeria strongly activated CD11b+ cells and to a less extend CD49b+ (NK) cells producing IFNγ in the spleen at old age (Fig 6B). Based on these results we analyzed the effect of Listeria immunizations on CD11b+ cells in the metastases of young and old mice. The percentage of CD11b+ cells was significantly increased in the metastases by Listeria compared with the saline group of young mice (Saline 73%, LM: 87%), and even more in the metastases of old mice (Saline: 62%; LM: 87%)(Fig. S1). We also measured the intracellular production of cytokines involved in activation or suppression of CD8 T cells such as IL-12, IL-10, IL-6, TNFα, and TGFβ in the metastases of young and old mice immunized with Listeria or saline. The percentage of CD11b+ cells producing IL-12, IL-10 or TGFβ in the metastases was significantly increased by Listeria compared with saline group at young age, while these cytokines were completely absent at old age. However, the percentage of CD11b+ cells producing IL-6, and TNFα significantly increased by Listeria compared with the saline group at both ages (Fig. 8).

Figure 8.

Listeria alters the function of CD11b+ cells in metastases of mice at young and old age. Young (3 m) and old (18 m) BALB/c mice were immunized with Listeria or controls as described in Fig. 1C (ET-frequently) Two days after the last immunization, mice were killed and CD11b+ cells producing IL-12, IL-10, IL-6, TNFα, or TGFβ were analyzed within the live CD45+ lymphocyte population in the metastases of young and old mice by flow cytometry. This experiment was performed once with n = 3 mice per group, and results were averaged. Unpaired t test. *p< 0.05, **<0.01,****<0.0001, is significant. The error bars represent the SEM.

We also analyzed the CD49b+ (NK) cell population. The percentage of CD49b+ cells increased significantly by Listeria compared with the saline group at young age (Saline: 0.2%; LM: 1.5%), but was hardly detectable at old age (Saline: 0.3%; LM: 0.25%)(Fig. S1). In more detail, the percentage of CD49b+ cells producing IFNγ increased slightly but significantly increased by Listeria compared with the saline group at young age (Saline: 0.01%; LM: 0.99%), while the production of IFNγ+ by CD49b+ cells was completely absent at old age (Saline: 0.05; LM: 0.03)( Fig. S2).

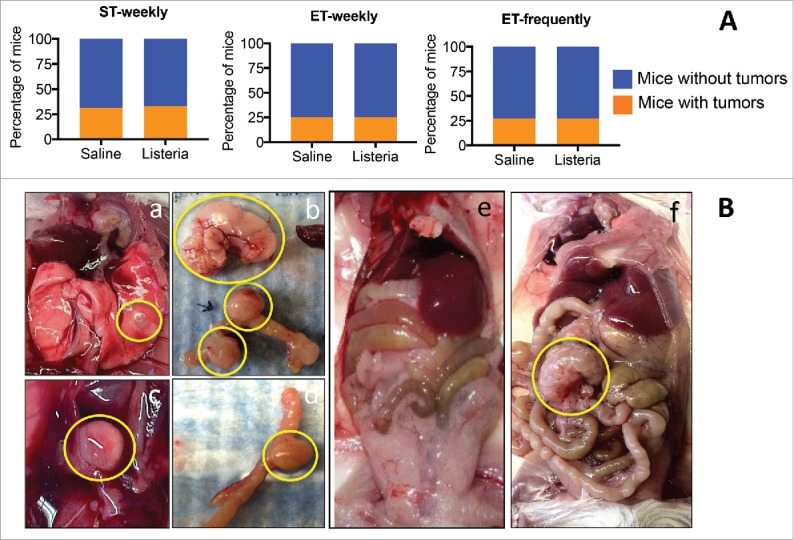

ET-frequently immunizations with Listeria did not reduce age-related spontaneous tumors

Since the old mice with 4T1 tumors also developed spontaneous age-related tumors, we were interested whether Listeria also had an effect on these tumors. Age-related spontaneous tumors in mice are predominantly from mesenchymal or hematopoetic origin,33 and are distinct from the 4T1-derived tumors and metastases. (All spontaneous tumors were verified by pathological analysis). We analyzed the effect of the 3 different immunization protocols on the spontaneous tumors. As shown in Fig. 9A, none of the immunization protocols showed a significant effect on the spontaneous tumors. After the ST-weekly immunizations we found that 31% and 33% of the mice exhibited spontaneous tumors in the saline and Listeria group, respectively. After the ET-weekly immunizations this was 25% and 25%, and after ET-frequent immunizations 27% and 27%. Examples of spontaneous tumors in the old BAB/c mice (18 months) are shown in Fig. 9B.

Figure 9.

Listeria has no effect on age-related spontaneous tumors in BALB/c mice. Young (3 m) and old (18 m) BALB/c mice were immunized with Listeria according the 3 different immunization protocols. Two days after the last immunization, these young and old mice were analyzed for the effect on tumor weight (A). ST-weekly: n = 5 mice per group; ET-weekly: n = 4 mice per group; ET-frequently: n = 5 mice per group. This experiment was performed 3 times (with an exception for the ET-weekly immunizations; this was performed once) and the results were averaged. No significant differences between saline and Listeria were found (Fisher's exact test). The error bars represent the SEM. Examples of age-related tumors are shown in Ba-f. a. Lung nodule; b. Large tumor in the peritoneal cavity, and tumors inside the gastro intestines (GI); c. A tumor in the peritoneal cavity; e. Young BALB/c mouse (3 m) without age-related tumors; f. Old BALB/c mouse (18m) with an age-related tumor in the peritoneal cavity.

Discussion

The age factor is often ignored in human clinical trials with cancer immunotherapy. However, studies in mice and humans clearly show that elderly react less efficient to flu and pneumococcal vaccines than young adults.3,34 Moreover, various groups, including our group, have shown that also cancer vaccination is less effective at older age.10-12,24

In the study presented here we analyzed whether Listeria immunizations could overcome immune senescence and immune suppression. Three different immunization strategies were tested (ST-weekly, ET-weekly, and ET-frequently) in young and old mice with metastatic breast cancer and their innate and adaptive immune responses were analyzed in relation to efficacy (effect on metastases and tumor). Only the ST-weekly immunizations were effective against metastases and tumors at young and old age. However, since this protocol was clinically less relevant, because the first immunization was given before tumor development, we focused on the 2 other protocols. ET-weekly immunizations were powerless because of the strong immune suppression in the TME at young and old age. This may be not surprising since high levels of IL-6 and TGFβ were found by ELISA in the TME of the 4T1 model.35 The immune system was completely suppressed at all levels (IFNγ by T cells, NK cells, and macrophages were hardly detectable), and no effect was observed on tumors or metastases. However, ET-frequently immunizations could overcome immune suppression and immune senescence, because strong CD8 T cells could be generated at young and old age in correlation with a nearly complete elimination of the metastases.

This study raised the question why Listeria had an effect on primary tumors after ST-weekly immunizations but not after ST-frequently immunizations? It is likely that the much higher doses of Listeria in the ST-weekly (0.5 × 107 CFU) than in the ET-frequently (104 CFU) immunizations may have plaid a role (ratio Listeria vs tumor cells is more favorable in the ST-weekly immunizations), combined with the absence of immune suppression during the first immunization (tumor cells can be immediately eliminated during the second immunization when primary tumors are still small). In another study we also found that higher doses of Listeria significantly reduced tumor growth in a pancreatic cancer model.36 In addition, Listeria survives better in a hypoxic environment,37 and metastases are known to be more hypoxic than primary tumors.

We also analyzed the effect of the different immunization protocols on the age-related spontaneous tumors. No significant effect of Listeria was observed on the spontaneous tumors. This may not be surprising because the ET-weekly and ET-frequently immunizations did not have an effect on tumors either. However, the ST-weekly did have an effect on 4T1 tumors but not on the spontaneous tumors. It is possible that the spontaneous tumors are less hypoxic. Also, at the time ST-weekly treatments were started the spontaneous tumors may have been too big (some tumors were 2–3 cm) to show a significant effect on the tumors. Of note is that the number of mice per group is too low for statistical power, since 25–33% only of the mice have spontaneous tumors (the number of mice per group varied between 5 and 15) while in the 4T1 model 100% of the mice bear 4T1-derived tumors.

Most interesting result from this study was that not only strong CD8 T cell responses to Listeria were observed, but also to TAA Mage-b. This was a remarkable result because Mage-b was not expressed by the Listeria. In previous studies we found that Listeria infected and killed tumor cells through high levels of ROS, and that Listeria-infected tumor cells became a target for Listeria-activated T cells.26 It is known that ROS induces immunogenic tumor cell death,30,31 and we have shown earlier that Listeria induces ROS.26 Since Mage-b is highly expressed by 4T1 tumors and metastases,28,32 and since Listeria induces ROS, we concluded that CD8 T cell responses to Mage-b were generated by Listeria through immunogenic tumor cell death. These results were later supported by the CD8 T cell responses to TAA Survivin and Mage-b in the presence and absence of MHC class Ia antibodies after ET-frequently immunizations with Listeria at young age.

Also, the innate immune responses were strongly activated by Listeria in the spleen. Particularly after ET-frequently immunizations innate immune responses were even stronger at old than at old age, i.e., the amount of IFNγ produced by NK cells and macrophages was higher at old than at young age, indicating that activation of the innate immune system by Listeria was not diminished by aging. Although it has been reported that also innate immune responses are affected by aging,38,39 apparently this is much less severe than the adaptive T cell responses to TAA. In addition, in a previous study we showed that Listeria induced IL-12 in MDSC,15 which in turn stimulates T cells.

As mentioned above, we concluded that the ET-frequent immunization strategy with the low doses of Listeria was able to overcome immune senescence and immune suppression. However, analysis of MHC class Ia and Ib-restricted T cell responses and CD8 T cell depletions in vivo in 4T1 mice at young and old age showed that our conclusion was partly wrong. While inhibition of CD8 T cells (isolated from spleens of tumor-bearing mice) restimulated with Mage-b or Survivin was observed with MHC class Ia at young age, this was not the case at old age. In contrast to MHC class Ia, antibodies to MHC class Ib antibodies inhibited CD8 T cell responses at both ages. We therefore studied whether CD8 T cell responses generated through Listeria contributed to the eradication of metastases at old age. CD8 T cell depletions in young and old age 4T1 mice, that received ET-frequently immunizations with low doses of Listeria, demonstrated regrowth of metastases at young but not at old age, indicating that the CD8 T cells contributed to reduction in metastases at young but not at old age. Despite the strong CD8 T cell responses to Listeria and TAA, none of these T cells apparently contributed to elimination of the metastases at old age.

Non-conventional MHC class Ib molecules are oligomorphic and diverse in function.40 It has been reported that MHC class Ib molecules bind to T cells restricted to mouse MHC H2-M3 and have been shown to react to bacterial infection, particularly Listeria monocytogenes.41 During a primary Listeria infection, H2-M3-restricted T cells mount an earlier and rapid immune response to Listeria before classical MHC Ia-restricted T cells. Although MHC class Ia and Ib-restricted T cells are both cytolytic and produce IFNγ, the study shows that the H2-M3 restricted T cells did not make sufficient memory cells while the MHC Ia restricted T cells did. Further more, another study confirmed that TAAs could be presented by MHC class Ib molecules to CTLs against tumor cells.42 It might be possible that in aged mice, our ET-frequent Listeria immunizations, activated nonclassical MHC class Ib-restricted CD8 T cells to the TAAs and Listeria, with poor memory effector function, and therefore lacked antitumor activity.

Despite this lack of antitumor CD8 T cells, Listeria immunizations strongly reduced the number of metastases at old age. However, ELISPOT data showed that Listeria activated CD49b+ cells and even stronger CD11b+ cells (producing high levels of IFNγ) in the spleen. Therefore, we analyzed CD11b+ and CD49b+ in the lymphocyte population (CD45+) directly in the metastases at young and old age of 4T1 mice that received Listeria or saline. Listeria immunizations resulted in a significant increase in the percentage of CD11b+ cells in the metastases of both young and old mice. We then analyzed the function of CD11b+ cells, by measuring the intracellular production of cytokines involved in activation or suppression of T cells such as IL-12, IL-10, IL-6, TNFα, and TGFβ in the metastases of young and old 4T1 mice. The most obvious difference was that the percentage of CD11b+ cells producing IL-12, IL-10 and TGFβ significantly increased by Listeria compared with the saline group in the young mice, but these cytokines were completely absent in the metastases of old mice. In earlier studies we have shown that Listeria induced IL-12 in MDSC in vitro, which are also CD11b+.15 In the current study, IL-12 may have been responsible for those T cells at young age that contributed to the reduction in the number of metastases. However, at old age IL-12 was completely absent and CD8 T cells did not have an effect on the metastases. Instead, Listeria significantly increased the percentage of CD11b+ cells producing IL-6, and TNFα in the metastases at both ages. It may be that the immune-stimulating IL-12 is dominant over the immune suppressive cytokines like IL-10, IL-6 and TGFβ. The function of TNFα is not clear here. TNFα has multiple functions.43 It could be a cancer killer (for instance by inducing apoptosis of tumor cells through interaction with TRAIL44), but also stimulates cancer growth, invasion, metastases or angiogenesis.45 Therefore, the function of TNFα needs to be analyzed in more detail.

The tumor microenvironment is extremely complex, and the macrophage population in particular. It is remarkable that 50–70% of the 4T1 metastases consists of CD11b+ cells and that this population even further increases by Listeria immunizations to 82–88%. Macrophages in breast cancer have very diverse functions (activated, immune suppressive, angiogenic, metastasis-associated, perivascular and invasive macrophages) as reported by the group of Pollard et al.46 Our results strongly suggest that Listeria has altered the function of macrophages in the TME. Thus, a deeper understanding of the role of Listeria in controlling the different types of macrophages involved in the development of metastatic breast cancer would be a promising new direction to study in cancer immunotherapy with Listeria at old age. Such studies are planned with old mice bearing 4T1 tumors and metastases, to analyze the effect of Listeria on the various types of macrophages describe by the group of Pollard, and then deplete the ”bad” macrophages by targeted treatment and conserve the “good” macrophages. Similarly, once we have more insight in the “good” and “bad” macrophages, FACS sorting of the “good” macrophages for in vitro killing of the tumor cells, and the “bad” macrophages for analyzing the activation of signaling pathways that leads to tumor cell growth, may shed light on the complex interactions of macrophages with the tumor cells in the TME of the 4T1 model.

While the percentage of CD49b+ cells slightly increased in the metastases by Listeria at young age, this population was hardly detectable at old age. Similarly, the percentage of CD49b+ cells producing IFNγ slightly increased by Listeria in the metastases at young age, but was completely absent at old age. Based on these results, we concluded that NK cells do not play a role in the Listeria-mediated reduction of metastases in the 41 model at old age.

In conclusion, the results of this study demonstrated that ET-frequent immunizations with Listeria resulted in a nearly complete elimination of the metastases at young and old age, but that different mechanisms contributed to this result.

Materials and methods

Animals

Normal female BALB/c mice (3 months and 18 months) were obtained from NIA/Charles River and maintained in the animal husbandry facility at Albert Einstein College of Medicine according to the Association and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care (AACAC) guidelines. All mice were kept under Bsl-2 conditions as required for Listeria immunizations.

Cells and cell culture

The 4T1 cell line, derived from a spontaneous mammary carcinoma in a BALB/c mouse and is highly metastatic in a BALB/c background (kindly provided by Dr. F. Miller, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor).47 4T1 cells were cultured in Dulbecco's Modified Eagle's Medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 1 mM mixed nonessential amino acids, 2 mM L-glutamine, insulin (0.5 USP units/ml), penicillin (100 units/ml), and streptomycin (100μg/ml) (Pen/Strep).

Attenuated listeria and plasmids

A highly attenuated Listeria monocytogenes (Listeria) has been used for immunizations of the 4T1 model, as described previously.19 The Listeria plasmid, pGG-34, expresses the positive regulatory factor (prfA) and Listeriolysin O (LLO).48 prfA regulates the expression of other virulence genes, and is required for survival in vivo and in vitro. The background strain XFL-7 lacks the prfA gene, and retains the plasmid in vitro and in vivo.48 The coding region for the C-terminal part of the LLO (cytolytic domain that binds cholesterol in the membranes) protein in the plasmid has been deleted, but Listeria is still able to escape host vacuole.49 Mutations have been introduced into the prfA gene and the remaining LLO (expressed by the pGG34 vector), which further reduced the pathogenicity of Listeria.49

Plasmids pcDNA3.1-Mage-b, pcDNA3.1-Survivin, and pcDNA3.1 were developed in the laboratory of Gravekamp. Mouse GM-CSF plasmid (CMV1-GM-CSF) was kindly provided by Dr Stephen Johnston (the Center for Innovations in Medicine, the Biodesign Institute at Arizona State University).50

Various immunization protocols and tumor challenge

(A) Semi-therapeutic immunization protocol (ST-weekly). BALB/c mice were immunized with Listeria-Mage-b, Listeria, or saline and challenged with 4T1 tumor cells as described previously. Briefly, one preventive immunization with 0.5 × 107 CFU of Listeria-Mage-b or Listeria (LD50 = 108 CFU) per 500μl saline, or saline alone was administered intraperitoneally (ip) before tumor challenge (day 0), followed by tumor challenge (0.5 × 105 4T1)(day 4) in the mammary fat pad, followed by 2 additional therapeutic immunizations ip with 0.5 × 107 CFU of Listeria per 500μl saline, or saline alone (days 7 and 14). The mice were killed 2 d after the last immunization, and analyzed for immune responses, frequency and location of metastases, and for tumor weight. All untreated 4T1 mice developed a primary tumor that extended to the chest cavity lining and metastasized predominantly to the mesenteric lymph nodes (MLN), and less frequently to the diaphragm, portal liver, spleen, and kidneys within 14 d (metastases were visible as nodules and counted by eye) as described previously.19 (B) Exclusive therapeutic immunization protocol at low frequency and long time-intervals (ET-weekly). Briefly, 3 therapeutic immunizations with 0.5 × 107 CFU of Listeria per 500μl saline, or saline alone were administered intraperitoneally (ip) (days 3, 10, and 17) after tumor challenge (104 4T1) in the mammary fat pad (day 0). The mice were killed 2 d after the last immunization, and analyzed for immune responses, frequency and location of metastases, and for tumor weight. (C) Exclusive therapeutic immunization protocol at high frequency and short time intervals (ET-frequently). Mice were immunized and challenged with tumor cells as described previously with. Briefly, therapeutic immunizations with 104 CFU of Listeria per 500 μl saline, or saline alone were administered ip every other day (days 4, 6, 8, 10, 12, and 14) after tumor challenge (104 4T1) (day 0). The mice were euthanized 2 d after the last immunization, and analyzed for immune responses, frequency and location of metastases, and for tumor weight. A schematic overview of all immunization protocols is shown in Fig. 1.

Elispot

Spleen cells were isolated from Listeria-immunized and control mice (2 d after the last immunization) and analyzed for macrophages (CD11b+), NK (CD49b+) and CD8 T cell responses by ELISPOT as described previously.19 To detect Listeria-induced immune responses in vitro, 2 × 105 isolated spleen cells were infected with 2 × 105 CFU of Listeria for 1 hour, and subsequently treated with gentamicin (50 μg/ml) to kill all extracellular bacteria but not the intracellular bacteria until the end of re-stimulation (72 hrs). After the 72hrs, the frequency of IFNγ-producing cells was determined by ELISPOT according to standard protocols (BD PharMingen, San Diego, CA) using an ELISPOT reader (CTL Immunospot S4 analyzer, Cellular Technology, Ltd, Cleveland, OH). To detect TAA-specific immune responses in vitro, 4 × 105 leukocytes isolated from spleens of treated or control mice were transfected with pcDNA3.1-Mage-b, pcDNA3.1-Survivin, pcDNA3.1 (1 μg of pcDNA3.1-TAA and 1 μg DNA of CMV-GM-CSF per 107 cells), using lipofectamin 2000, and cultured for 72 hrs, in the presence or absence of antibodies to MHC class Ia (1 μg/ml) or Ib (2 μg/ml) antibodies. We also restimulated the spleen cells with Survivin peptides 100 μg/ml (incubated with bone marrow (BM) cells (105 BM cells /100 μl), that were cultured with GM-CSF (10 ng/ml) and IL-4 (10 ng/ml) for 6 days), matching the H2-D haplotype (GWEPDDNPI),51 in the presence or absence of MHC class Ia (1 μg/ml), or MHC class Ib (2 μg/ml). To determine CD8 T cell, NK cell or macrophage responses, spleen cells were depleted for CD8 T cells, NK cells or macrophages using magnetic bead depletion techniques according to the manufacturer's instructions (Miltenyi Biotech, Auburn, CA). All antibodies were purchased from BD PharMingen.

CD8 T cell depletions in vivo

CD8 T cells were depleted in 4T1-tumor-bearing young (3 months) and old (18 months) BALB/c mice with 400 μg of anti-CD8 antibodies (5 injections, 3 d apart)(H35) (kindly provided by Dr. Lauvau, Dept of Microbiology and Immunology of Einstein)52 concomitantly with the Listeria immunizations (6 injections). All mice were killed 2 d after the last anti-CD8 treatment, and analyzed for the number of metastases and for tumor weight. After depletion, the percentage of CD8 T cells in the spleen was less then 1%. As control, isotype-matched rat antibodies against horseradish peroxidase N (HRPN) were used.

Flow cytometry

Immune cells from spleens, blood, and metastases from 4T1 mice were isolated as described previously.15 Briefly, red blood cells from blood or tumor cells were lysed according to standard protocols, and the remaining leukocyte population was used for analysis. Single cell suspensions were obtained from primary tumors using GentleMacs combined with a mild treatment of the cells using Collagenase, Dispase, and DNAse I, according to the manufacturers instructions (Miltenyi Biotech, Auburn, CA).

Cells were first incubated with an Fc blocked (anti-CD16), and subsequently with the antibodies for the identification of different cell types. For macrophages anti-CD11b and for NK cells anti-CD49b antibodies were used. To detect the production of intracellular cytokines, the cells were cultured with Golgi-plug (1 μg/106 cells) for 6 hrs, and the cytofix/cytoperm kit from BD PharMingen according to manufacturer's instructions, and antibodies to IL-12, IL-10, IL-6, TNFα, and TGFβ was used. Appropriate isotype controls were used for each sample. Depending on the sample size, 10,000–50,000 cells were acquired by scanning using a Fluorescence Activated Cell Sorter (flow cytometry) (Beckton and Dickinson; Facscalibur), and analyzed using FlowJo 7.6 software. Cell debris and dead cells were excluded from the analysis based on scatter signals and use of Fixable Blue or Green Live/Dead Cell Stain Kit (Invitrogen). All antibodies were purchased from BD PharMingen or eBiosciences.

Statistical analysis

To statistically analyze the effects of Listeria on the growth of metastases and tumors in the 4T1 model, Mann-Whitney and the analysis of variance (ANOVA) (one way) were used. To analyze the effects of Listeria on immune responses by ELISPOT and flow cytometry the Unpaired t test was used. To analyze the effect of Listeria on spontaneous tumors Fisher's exact test was used. Values p < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. *p < 0.05, **<0.01, ***<0.001, ****<0.0001 is significant.

Supplementary Material

Disclosure of potential conflicts of interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Rani Sellers for her excellent pathological analyses and discussions regarding the spontaneous tumors in this manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by NIA/NCI grant 1RO1 AG023096–01, training grant NIH1T32 Ag23475, The Paul F Glenn Center for the Biology of Human Aging Research 34118A, and the Nathan Shock Center for Aging Research (P30AG0380072; Pilot Grant).

References

- 1.Miller RA. The aging immune system: Primer and prospectus. Science 1996; 273:70-74; PMID:8658199; https://doi.org/ 10.1126/science.273.5271.70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Del Giudice G, Weinberger B, Grubeck-Loebenstein B. Vaccines for the elderly. Gerontology 2015; 61:203-10; PMID:25402229; https://doi.org/ 10.1159/000366162 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McElhaney JE, Meneilly GS, Lechelt KE, Bleackley RC. Split-virus influenza vaccines: Do they provide adequate immunity in the elderly? J Gerontol 1994; 49:M37-43; PMID:8126350; https://doi.org/ 10.1093/geronj/49.2.M37 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Utsuyama M, Hirokawa K, Kurashima C, Fukayama M, Inamatsu T, Suzuki K, Hashimoto W, Sato K. Differential age-change in the numbers of CD4+CD45RA+ and CD4+CD29+ T cell subsets in human peripheral blood. Mech Ageing Dev 1992; 63:57-68; PMID:1376382; https://doi.org/ 10.1016/0047-6374(92)90016-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tamir A, Eisenbraun MD, Garcia GG, Miller RA. Age-dependent alterations in the assembly of signal transduction complexes at the site of T cell/APC interaction. J Immunol 2000; 165:1243-51; PMID:10903722; https://doi.org/ 10.4049/jimmunol.165.3.1243 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wack A, Cossarizza A, Heltai S, Barbieri D, D'Addato S, Fransceschi C, Dellabona P, Casorati G. Age-related modifications of the human alphabeta T cell repertoire due to different clonal expansions in the CD4+ and CD8+ subsets. Int Immunol 1998; 10:1281-88; PMID:9786427; https://doi.org/ 10.1093/intimm/10.9.1281 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Effros RB. Replicative senescence of CD8 T cells: Effect on human ageing. Exp Gerontol 2004; 39:517-24; PMID:15050285; https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.exger.2003.09.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Effros RB. Role of T lymphocyte replicative senescence in vaccine efficacy. Vaccine 2007; 25:599-604; PMID:17014937; https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.vaccine.2006.08.032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Filaci G, Fravega M, Negrini S, Procopio F, Fenoglio D, Rizzi M, Brenci S, Contini P, Olive D, Ghio M et al.. Nonantigen specific CD8+ T suppressor lymphocytes originate from CD8+CD28- T cells and inhibit both T-cell proliferation and CTL function. Hum Immunol 2004; 65:142-56; PMID:14969769; https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.humimm.2003.12.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Castro F, Leal B, Denny A, Bahar R, Lampkin S, Reddick R, Lu S, Gravekamp C. Vaccination with Mage-b DNA induces CD8 T-cell responses at young but not old age in mice with metastatic breast cancer. Br J Cancer 2009; 101:1329-37; PMID:19826426; https://doi.org/ 10.1038/sj.bjc.6605329 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lustgarten J, Dominguez AL, Thoman M. Aged mice develop protective antitumor immune responses with appropriate costimulation. J Immunol 2004; 173:4510-15; PMID:15383582; https://doi.org/ 10.4049/jimmunol.173.7.4510 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Provinciali M, Smorlesi A, Donnini A, Bartozzi B, Amici A. Low effectiveness of DNA vaccination against HER-2/neu in ageing. Vaccine 2003; 21:843-8; PMID:12547592; https://doi.org/ 10.1016/S0264-410X(02)00530-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Provinciali M, Argentati K, Tibaldi A. Efficacy of cancer gene therapy in aging: Adenocarcinoma cells engineered to release IL-2 are rejected but do not induce tumor specific immune memory in old mice. Gene Ther 2000; 7:624-32; PMID:10819579; https://doi.org/ 10.1038/sj.gt.3301131 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gravekamp C, Jahangir A. Is cancer vaccination feasible at older age? Exp Gerontol 2014; 54:138-44; PMID:24509231; https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.exger.2014.01.025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chandra D, Jahangir A, Quispe-Tintaya W, Einstein MH, Gravekamp C. Myeloid-derived suppressor cells have a central role in attenuated Listeria monocytogenes-based immunotherapy against metastatic breast cancer in young and old mice. Br J Cancer 2013; 108:2281-90; PMID:23640395; https://doi.org/ 10.1038/bjc.2013.206 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Grizzle WE, Xu X, Zhang S, Stockard CR, Liu C, Yu S, Wang J, Mountz JD, Zhang HG. Age-related increase of tumor susceptibility is associated with myeloid-derived suppressor cell mediated suppression of T cell cytotoxicity in recombinant inbred BXD12 mice. Mech Ageing Dev 2007; 128:672-80; PMID:18036633; https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.mad.2007.10.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Couzin-Frankel J. Breakthrough of the year 2013. Cancer Immunotherapy Sci 2013; 342:1432-33; PMID:24357284; https://doi.org/ 10.1126/science.342.6165.1432 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gravekamp C. The impact of aging on cancer vaccination. Curr Opin Immunol 2011; 23:555-60; PMID:21763118; https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.coi.2011.05.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kim SH, Castro F, Gonzalez D, Maciag PC, Paterson Y, Gravekamp C. Mage-b vaccine delivered by recombinant Listeria monocytogenes is highly effective against breast cancer metastases. Br J Cancer 2008; 99:741-9; PMID:18728665; https://doi.org/ 10.1038/sj.bjc.6604526 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ostrand-Rosenberg S, Sinha P. Myeloid-derived suppressor cells: Linking inflammation and cancer. J Immunol 2009; 182:4499-506; PMID:19342621; https://doi.org/ 10.4049/jimmunol.0802740 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Diaz-Montero CM, Salem ML, Nishimura MI, Garrett-Mayer E, Cole DJ, Montero AJ. Increased circulating myeloid-derived suppressor cells correlate with clinical cancer stage, metastatic tumor burden, and doxorubicin-cyclophosphamide chemotherapy. Cancer Immunol Immunother 2009; 58:49-59; PMID:18446337; https://doi.org/ 10.1007/s00262-008-0523-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Quispe-Tintaya W, Chandra D, Jahangir A, Harris M, Casadevall A, Dadachova E, Gravekamp C. Nontoxic radioactive Listeria(at) is a highly effective therapy against metastatic pancreatic cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2013; 110:8668-73; PMID:23610422; https://doi.org/ 10.1073/pnas.1211287110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hiratsuka S, Watanabe A, Aburatani H, Maru Y. Tumour-mediated upregulation of chemoattractants and recruitment of myeloid cells predetermines lung metastasis. Nat Cell Biol 2006; 8:1369-75; PMID:17128264; https://doi.org/ 10.1038/ncb1507 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chandra D, Gravekamp C. Myeloid-derived suppressor cells: Cellular missiles to target tumors. Oncoimmunology 2013; 2:e26967; PMID:24427545; https://doi.org/ 10.4161/onci.26967 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tilney LG, Portnoy DA. Actin filaments and the growth, movement, and spread of the intracellular bacterial parasite, Listeria monocytogenes. J Cell Biol 1989; 109:1597-608; PMID:2507553; https://doi.org/ 10.1083/jcb.109.4.1597 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kim SH, Castro F, Paterson Y, Gravekamp C. High efficacy of a Listeria-based vaccine against metastatic breast cancer reveals a dual mode of action. Cancer Res 2009; 69:5860-66; PMID:19584282; https://doi.org/ 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-4855 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gravekamp C, Paterson Y. Harnessing Listeria monocytogenes to target tumors. Cancer Biol Ther 2010; 9:257-65; PMID:20139702; https://doi.org/ 10.4161/cbt.9.4.11216 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gomez-Cabrero A, Wrasidlo W, Reisfeld RA. IMD-0354 targets breast cancer stem cells: A novel approach for an adjuvant to chemotherapy to prevent multidrug resistance in a murine model. PLoS One 2013; 8:e73607; PMID:24014113; https://doi.org/ 10.1371/journal.pone.0073607 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kim SH, Castro F, Gonzalez D, Maciag PC, Paterson Y, Gravekamp C. Mage-b vaccine delivered by recombinant Listeria monocytogenes is highly effective against breast cancer metastases. Br J Cancer 2008; 99:741-9; PMID:18728665; https://doi.org/ 10.1038/sj.bjc.6604526 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zitvogel L, Apetoh L, Ghiringhelli F, Kroemer G. Immunological aspects of cancer chemotherapy. Nat Rev Immunol 2008; 8:59-73; PMID:18097448; https://doi.org/ 10.1038/nri2216 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zitvogel L, Kepp O, Senovilla L, Menger L, Chaput N, Kroemer G. Immunogenic tumor cell death for optimal anticancer therapy: The calreticulin exposure pathway. Clin Cancer Res 2010; 16:3100-04; PMID:20421432; https://doi.org/ 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-2891 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chandra D, Quispe-Tintaya W, Jahangir A, Asafu-Adjei D, Ramos I, Sintim HO, Zhou J, Hayakawa Y, Karaolis DK, Gravekamp C. STING ligand c-di-GMP improves cancer vaccination against metastatic breast cancer. Cancer Immunol Res 2014; 2:901-10; PMID:24913717; https://doi.org/ 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-13-0123 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.DePinho RA. The age of cancer. Nature 2000; 408:248-54; PMID:11089982; https://doi.org/ 10.1038/35041694 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.McElhaney JE, Meneilly GS, Lechelt KE, Beattie BL, Bleackley RC. Antibody response to whole-virus and split-virus influenza vaccines in successful ageing. Vaccine 1993; 11:1055-60; PMID:8212827; https://doi.org/ 10.1016/0264-410X(93)90133-I [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gravekamp C, Leal B, Denny A, Bahar R, Lampkin S, Castro F, Kim SH, Moore D, Reddick R. In vivo responses to vaccination with Mage-b, GM-CSF and thioglycollate in a highly metastatic mouse breast tumor model, 4T1. Cancer Immunol Immunother 2008; 57:1067-77; PMID:18094967; https://doi.org/ 10.1007/s00262-007-0438-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chandra D, Selvanesan BC, Yuan Z, Libutti SK, Koba W, Beck A, Zhu K, Casadevall A, Dadachova E, Gravekamp C. 32-Phosphorus selectively delivered by listeria to pancreatic cancer demonstrates a strong therapeutic effect. Oncotarget 2017; 8:20729-740; PMID:28186976; https://doi.org/ 10.18632/oncotarget.15117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Toledo-Arana A, Dussurget O, Nikitas G, Sesto N, Guet-Revillet H, Balestrino D, Loh E, Gripenland J, Tiensuu T, Vaitkevicius K et al.. The Listeria transcriptional landscape from saprophytism to virulence. Nature 2009; 459:950-6; PMID:19448609; https://doi.org/ 10.1038/nature08080 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gomez CR, Nomellini V, Faunce DE, Kovacs EJ. Innate immunity and aging. Exp Gerontol 2008; 43:718-28; PMID:18586079; https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.exger.2008.05.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ogata K, Yokose N, Tamura H, An E, Nakamura K, Dan K, Nomura T. Natural killer cells in the late decades of human life. Clin Immunol Immunopathol 1997; 84:269-75; PMID:9281385; https://doi.org/ 10.1006/clin.1997.4401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rodgers JR., Cook RG. MHC class Ib molecules bridge innate and acquired immunity. Nat Rev Immunol 2005; 5:459-71; PMID:15928678; https://doi.org/ 10.1038/nri1635 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kerksiek KM., Busch DH, Pilip IM, Allen SE, Pamer EG. H2-M3-restricted T cells in bacterial infection: Rapid primary but diminished memory responses. J Exp Med 1999; 190:195-204; PMID:10432283; https://doi.org/ 10.1084/jem.190.2.195 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Griffiths E, Ong H, Soloski MJ, Bachmann MF, Ohashi PS, Speiser DE. Tumor defense by murine cytotoxic T cells specific for peptide bound to nonclassical MHC class I. Cancer Res 1998; 58:4682-87; PMID:9788622 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Aggarwal BB, Gupta SC, Kim JH. Historical perspectives on tumor necrosis factor and its superfamily: 25 years later, a golden journey. Blood 2012; 119:651-65; PMID:22053109; https://doi.org/ 10.1182/blood-2011-04-325225 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wiley SR, Schooley K, Smolak PJ, Din WS, Huang CP, Nicholl JK, Sutherland GR, Smith TD, Rauch C, Smith CA et al.. Identification and characterization of a new member of the TNF family that induces apoptosis. Immunity 1995; 3:673-82; PMID:8777713; https://doi.org/ 10.1016/1074-7613(95)90057-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wang X, Lin Y. Tumor necrosis factor and cancer, buddies or foes? Acta Pharmacol Sin 2008; 29:1275-88; PMID:18954521; https://doi.org/ 10.1111/j.1745-7254.2008.00889.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Qian BZ, Pollard JW. Macrophage diversity enhances tumor progression and metastasis. Cell 2010; 141:39-51; PMID:20371344; https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.cell.2010.03.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Aslakson CJ, Miller FR. Selective events in the metastatic process defined by analysis of the sequential dissemination of subpopulations of a mouse mammary tumor. Cancer Res 1992; 52:1399-405; PMID:1540948 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gunn GR, Zubair A, Peters C, Pan ZK, Wu TC, Paterson Y. Two Listeria monocytogenes vaccine vectors that express different molecular forms of human papilloma virus-16 (HPV-16) E7 induce qualitatively different T cell immunity that correlates with their ability to induce regression of established tumors immortalized by HPV-16. J Immunol 2001; 167:6471-79; PMID:11714814; https://doi.org/ 10.4049/jimmunol.167.11.6471 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Singh R, Dominiecki ME, Jaffee EM, Paterson Y. Fusion to Listeriolysin O and delivery by Listeria monocytogenes enhances the immunogenicity of HER-2/neu and reveals subdominant epitopes in the FVB/N mouse. J Immunol 2005; 175:3663-73; PMID:16148111; https://doi.org/ 10.4049/jimmunol.175.6.3663 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chambers RS, Johnston SA. High-level generation of polyclonal antibodies by genetic immunization. Nat Biotechnol 2003; 21:1088-92; PMID:12910245; https://doi.org/ 10.1038/nbt858 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Siegel S, Wagner A, Schmitz N, Zeis M. Induction of antitumour immunity using survivin peptide-pulsed dendritic cells in a murine lymphoma model. Br J Haematol 2003; 122:911-14; PMID:12956760; https://doi.org/ 10.1046/j.1365-2141.2003.04535.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Letourneur F, Gabert J, Cosson P, Blanc D, Davoust J, Malissen B. A signaling role for the cytoplasmic segment of the CD8 alpha chain detected under limiting stimulatory conditions. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1990; 87:2339-43; PMID:2107551; https://doi.org/ 10.1073/pnas.87.6.2339 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.