Abstract

Adenoid cystic carcinoma (ACC) is a relatively rare slow growing and often-aggressive epithelial-myoepithelial neoplasm that arises in multiple organs including the skin. The t(6;9) (q22–23;p23–24) translocation, resulting in a MYB-NFIB gene fusion has been found in ACCs from the salivary glands and other organs. Recently, MYB aberrations occurring in a subset (40%) of primary cutaneous ACC (PCACC) examples was described. Herein, we report 3 additional cases of PCACC harboring MYB aberrations. The tumors presented in 3 males aged 43, 81 and 55 years old and affected the extremities in the first 2 patients and the scalp in the third one. None of the patients had history of prior or concurrent ACC elsewhere. Lesions exhibited the classic ACC morphology of nests of basaloid cells arranged in cribriform and adenoid patterns. Sentinel lymph node biopsy was performed in two cases with one case showing lymph node positivity. Fluorescence in situ hybridization with break-apart probes for MYB and NFIB loci revealed that 2 cases showed MYB rearrangements while one case showed loss of one MYB signal. None of the cases showed NFIB rearrangements. We contribute with 3 additional cases of PCACC exhibiting MYB aberrations, the apparent driving genetic abnormality in these tumors.

Introduction

Adenoid cystic carcinoma (ACC) is a rare malignancy that can arise in a variety of gland-bearing organs, most notoriously in the salivary glands, breast as well as in upper and lower respiratory tracts. A readily recognizable and reproducible histomorphologic pattern characterizes this entity, regardless of the organ of origin. All ACC lesions are formed by a mixture of basaloid cells and more subtle myoepithelial cells that are disposed in mixture of 3 main architectural patterns: cribriform, solid and tubular1. Primary cutaneous ACC (PCACC) is a rare occurrence. After excluding ACCs originating in the periocular and ear canal regions, few reports and small series of PCACC cases can be found with an overall count of 114 cases documented to date in the English literature. This list includes the first report by Boggio in 19752, as well as 3 tumors that predate that publication and were reported under different rubrics3–5 and were later retrospectively deemed to be PCACCs6. An epidemiologic study utilizing data from the United States (U.S.) Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) program indicated that 152 cases of PCACC were diagnosed (not necessarily published) in the 30-year period spanning from 1976 to 2005, yielding an incidence rate of 0.23 cases per 1 million people per year7. This SEER-based study also pointed out that PCACC arises in older patients with a median age of 64 years (mean 63 years, range 23–94 years), has a predilection for the head and neck/face region and a low-grade yet protracted clinical course including multiple recurrences7. Although very useful and important, SEER-based studies could be afflicted by potential “contamination” from misdiagnosed cases, since the actual pathology of the cases is usually not reviewed. Although ACCs are overall easy to recognize, overlap with other entities exists. In the particular case of PCACC the following entities should be included in the differential diagnosis: basal cell carcinoma (BCC) with prominent adenoid features8 and the rare adnexal tumors apocrine cribriform carcinoma (ACrC)9 and polymorphous sweat gland carcinoma (PSGC)10. Occasionally, PCACC tumors will be difficult to distinguish from other basaloid adnexal tumors like cylindroma and spiradenoma, particularly if some overlapping features are present1. Following the description of the t(6;9)(q22–23;p23–24) MYB-NFIB translocation in head and neck and breast ACCs11–13, subsequent studies showed that this aberration was also found in ACCs arising from other anatomical locations including the skin14. Herein, we present our findings from 3 additional PCACC tumors that include analysis of MYB and NFIB aberrations by FISH studies as well as follow up clinical information. In addition, given the rarity of PCACC, we underwent an extensive review of the English literature on this particular subject.

Materials and Methods

Three PCACC cases were captured from the archives of Baystate Medical Center (BMC) (Cases 1 and 2) and Moffitt Cancer Center (MCC) (Case 3) Pathology Departments. Available clinicopathologic information, including clinical pictures and follow up information, were reviewed. Importantly, the possibility of a cutaneous metastasis from a potential primary ACC tumor arising in a different anatomical location (head and neck, lung, breast, etc.) was completely ruled out in all patients. The Hematoxylin and Eosin (H&E) histomorphologic features of the tumors were re-reviewed in all 3 cases. Fluorescence In Situ Hybridization (FISH) studies on interphase nuclei were performed at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (MSKCC) using a two-color custom bacterial artificial chromosomes (BAC) break-apart probe mix directed towards regions flanking the MYB and NFIB loci (red: centromeric, green: telomeric). This probe mix was applied on formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) 4-μm thick unstained sections and successive nuclei (200) were examined using a Zeiss fluorescence microscope (Zeiss Axioplan, Oberkochen, Germany), controlled by Isis 5 software (Metasystems).

A review of the literature on PCACC was performed. A PubMed search using “primary cutaneous adenoid cystic carcinoma” was carried out and all publications on the subject that were available in English up to the date of this manuscript’s preparation (July-August, 2016) were reviewed. Several epidemiologic and clinicopathologic parameters were recorded if available.

In order to specifically study the primary cutaneous cases, we excluded ACC cases arising from the periocular and outer ear glandular systems as well as cases that had originated in anatomical areas in which a primary ACC from other organs would be impossible to rule out (e.g. “parotid region”).

Results

Case 1

The first tumor arose in a 43 year-old male as a slow growing, non-tender 7-centimeter (cm) right forearm mass that developed in a 10-year period (Figure 1A). The lesion was excised and appeared grossly as a well-circumscribed mass with homogeneous grey-tan cut surfaces exhibiting tiny cystic spaces (Figure 2A). Microscopic examination revealed a basaloid tumor exhibiting the classic morphologic picture with an ACC with a predominant cribriform growth pattern (Figure 2B). Two cell types formed the neoplasm: basaloid and myoepithelial (Figure 2C). The cells formed numerous cystic spaces that were lined by Periodic Acid Schiff (PAS) positive basal membrane material (not shown). No perineural invasion was noted. Break-apart probe FISH analysis for the MYB locus revealed a balanced rearrangement with the MYB split present in the majority of the cells (Figure 3A, arrows), the NFIB region was not rearranged (not shown).

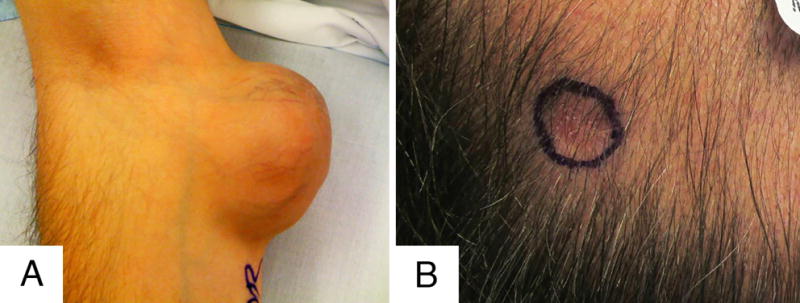

Figure 1.

Clinical Features of the lesions in patients 1 (A) and 3 (B). Note the well demarcated and exophytic appearance of the large long-standing mass from case 1 in contrast to the infiltrative nature of the subcutaneous scalp lesion from case 3.

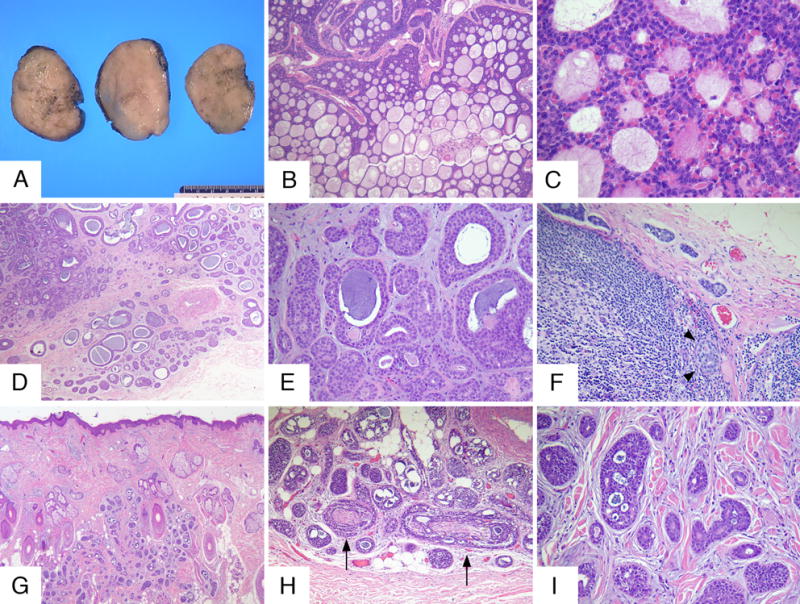

Figure 2.

Representative gross and histopathologic findings of the 3 cases are shown in this composite: rows A-C, D-F and G-I represent cases 1, 2 and 3 respectively. Grossly, the tumor from case 1 was well circumscribed and showed homogeneous grey-tan cut surfaces (A). Microscopically, the tumor was composed of basaloid cells arranged in cords, nests and showing a striking cribriform pattern (B). Higher power examination revealed the presence of a mixture of basaloid and myoepithelial cells (C). Cases 2 and 3 showed tumors with similar morphologic features with infiltrating borders and composed of basaloid cells disposed in a corded, tubular and focally cribriform patterns (D, E and G-I). Case 2 showed metastatic tumor was present in one sentinel lymph node (F, arrowheads show intraparenchymatous nest). Perineural invasion was found in cases 2 (not shown) and 3 (H, arrows).

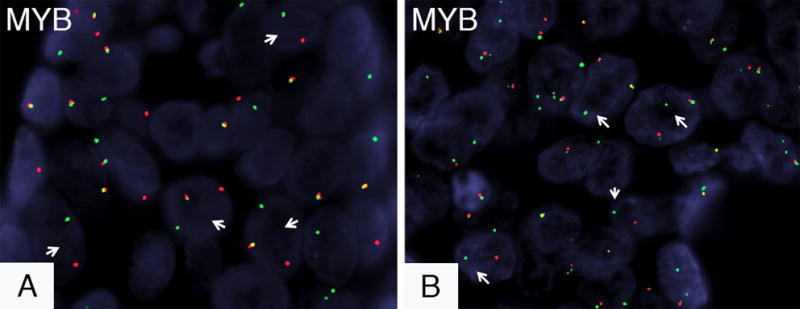

Figure 3.

Selected pictures of FISH findings. The red and green signals represent the centromeric and telomeric probes, respectively. The first two cases showed balanced MYB rearrangements with the balanced MYB rearrangement seen in case 2 being shown in A (arrows point to the split green and red signals, the yellow signal shows alleles with preserved MYB loci). An unbalanced MYB aberrancy was seen in case 3 represented by the presence of multiple MYB copies per cell, with a subset of cells exhibiting deletions of the 3′ portion of MYB (B, arrows show the loss of the centromeric red signal, note the multiple signals per cell).

The tumor was present at the deep margin in the initial excision and two subsequent re-excisions were performed which were negative for residual component. The area was postoperatively irradiated. Although the patient was deemed to be free of disease following surgery and radiotherapy, the tumor locally recurred approximately 60 months after the diagnosis, exhibiting identical morphologic features to the original tumor (no higher grade progression).

Case 2

The second case occurred in an 81 year-old male with history of gastric diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) status post R-CHOP chemotherapy that presented with a right tibial cutaneous nodule of several years in duration that became increasingly tender. Upon excision, the tumor proved to be a highly infiltrative neoplasm invading to a depth of 10 millimeters (mm) that was composed of basaloid and myoepithelial cells disposed in a predominantly tubular and focally cribriform array (Figure 2D). Bluish mucinous/myxoid material was found both in the stroma and within cystic spaces (Figures 2E). There was perineural invasion (not shown) and the tumor was present at the deep margin. Upon FISH analysis, this tumor revealed a balanced MYB split and a preserved NFIB (not shown).

A sentinel lymph node biopsy was performed and yielded one out of two inguinal lymph nodes (1/2) being positive for metastatic disease (Figure 2F, arrowheads), and the subsequent completion dissection demonstrated 7 negative lymph nodes (0/7). Three subsequent re-excisions with skin grafting were necessary to obtain clear margins and adjuvant radiotherapy of the area was carried out. The patient remains free of disease 48 months following the diagnosis.

Case 3

A 55 year-old male complaining of a tender subcutaneous indurated lesion on the left scalp (Figure 1B) represents the third and final case. An excision showed a tumor composed of infiltrating basaloid cells that were arranged in tubular and cribriform patterns, which were deeply invasive into the subcutaneous adipose tissue (Figures 2G–2I). The lesion invaded to a depth of 8 mm and measured 7 mm in width. Multifocal perineural invasion (Figure 2H, arrows) was seen and the tumor involved the deep margin. FISH studies for MYB and NFIB showed that, in contrast to the first two cases, this particular tumor exhibited three copies of MYB per cell with a subset of tumor cells showing deletions of the centromeric (3′ portion) of the MYB locus (Figure 3B, arrows).

A sentinel lymph node biopsy procedure was performed, yielding one negative right cervical lymph node (0/1). Radiotherapy was administered and a subsequent re-excision revealed no evidence of residual tumor. The patient was found to be free of disease 7 months after the surgery.

Review of the Literature

The PubMed-based search revealed a total of 114 PCACC published cases the majority of which were part of case reports1–7, 9, 15–60, with only a couple of small series61, 62 and 4 relatively large series first authored by Seab63, Urso64, Ramakrishnan65 and North14, which included 10, 5, 27 and 19 PCACC cases, respectively. After including our 3 cases, complete clinical information was found in 116 cases with one case that was reported as part of an immunohistochemical study did not include any clinical data56. PCACC tumors had a tendency to affect older individuals with the median age being 60 years old (mean: 62, range: 14–92), while the gender distribution was almost equal among males (n = 59) and females (n = 57). Regarding anatomical location, almost half of the lesions (n = 53, 46%) arose in the head and neck region; particularly in the scalp (n = 40, 34% of total cases), followed by the thoracic region (n = 15, 13%). Tumors arose less frequently in the abdomen (n = 13, 11%), upper (n = 11, 10%) and lower (n= 10, 8%) limbs. Likewise, the back (n = 8, 7%) and the genitalia/perineal area (n = 6, 5%) were also infrequently involved. Tumors developed over long periods of time, usually decades, with the median time to diagnosis/surgery being 330 months/27.5 years with an average of 84.5 months/7 years (range 1 – 660 months) (n = 57). Diagnosis was delayed in 5 cases, as the tumors were misdiagnosed for several years and even decades as either as benign adnexal tumors (syringoma24 and cylindroma35) or as basal cell carcinomas37, 42, 48. Perineural invasion (PNI) was found in 51 cases (55%) in which this parameter was available (n = 93) and local recurrences were seen in 33 (37%) of the 89 cases with follow up information. Treatment strategies included local excision, wide local excision with or without radiotherapy with variable results. Micrographic surgery technique (Mohs) was performed in 8 cases with excellent results18, 27, 31, 37, 40, 41, 48, 59. Multiple local recurrences were observed in 6 cases. Curiously, among the recurrent cases, an identical percentage of cases (36%) exhibited presence (16/45) and absence (8/22) of PNI, possibly suggesting occult foci of PNI in the cases deemed as negative. However, this assumption does not take in consideration the mode of treatment. The overall median time from last surgery to recurrence was also protracted: 45 months (mean 59 months, range 1 – 240). From the 84 cases in which this information was available, metastases were found in 15 cases (18%) with 10 cases showing visceral spread and 5 presenting only regional lymph node metastases31, 35, 54, 65 (including our Case 2). The majority of distant metastases were either seen solely affecting the lungs (6 cases)15, 32, 33, 63, 65 or lungs and brain (2 cases), with the remainder 2 cases metastasizing to the liver and pericardium. Two cases with visceral metastases also shown preceding regional lymph node involvement and 2 cases showed spread first to lungs and then brain. The median time from diagnosis/surgery to the first metastasis was 60.5 months (mean: 85 months, 0– 240). Most of the cases that developed metastases were related with local recurrences (12/14), recurrence information was not available in 1 metastatic case.

The results of this review, as well as the 3 cases reported herein, arranged in chronological order, are included in a table available in the Supplementary Materials section.

Discussion

Adnexal cutaneous neoplasms share some common entities with tumors derived from glandular organs found elsewhere in the body, most notoriously the salivary glands and the breast, which are basically “modified sweat glands”. One of such tumors is the epithelial-myoepithelial malignancy known as adenoid cystic carcinoma (ACC). This tumor very rarely arises in the skin, likely related to adnexal structures. Diagnosis of bona fide primary cutaneous adenoid cystic carcinoma (PCACC) requires careful exclusion of both metastatic disease and/or contiguous cutaneous extension of an ACC arising from the breast, salivary glands or other possible non-cutaneous primary origin. This is a sine qua non requirement for PCACC diagnosis and forms part of the criteria laid by Seab and colleagues in their PCACC series63, along with the following: tumors have to be dermal-based, show basaloid cells with at least cribriform growth pattern and be accompanied by mucin (glandular and/or stromal) and/or stromal hyalinization.

Although PCACC was first described as such by Boggio and colleagues2, there were at least 3 examples already reported, but under different names3–5, including the first documented description of this tumor back in 1951, authored by no other than Dr. Arthur Purdy Stout3. These 3 tumors were ultimately reclassified as PCACC in a subsequent publication by Cooper and colleagues6.

Our literature review yielded a total of 117 cases, including the 3 PCACC cases reported herein. After analyzing the data, we arrived to similar conclusions to the ones in the above cited SEER-based study7. Thus, we confirmed that PCACC preferentially affects older individuals (median 60 years of age) and behaves as slow-growing, locally aggressive neoplasm with a tendency to show perineural invasion, seen in 55% of cases, local recurrence, which presented in 35% of cases and a low, albeit considerable, metastatic potential (15% of cases metastasized). Interestingly, we found that both local recurrences and metastases often appeared many months, even decades, after the surgery, with a median of 45 and 60.5 months, respectively. Thus, long-term follow up is warranted and should be performed in these patients.

The other aim of this report was to contribute to the understanding of the molecular underpinnings of PCACC. Following the description of the t(6;9)(q22–23;p23–24) in salivary gland and breast ACCs by Dr. Göran Stenman’s group11–13, this chromosomal aberration was found to be present in a ACCs arising form other gland-bearing organs elsewhere in the body. This translocation results in the production of a MYB-NFIB fusion, which is believed to be key in the generation of these neoplasms. The MYB proto-oncogene (6q22–q23) regulates, through its protein product the MYB transcription factor, normal hematopoiesis, neural development and colonic crypt homeostasis factor66, among other processes. MYB can be activated through overexpression or inappropriate expression, structural alteration in addition to genomic rearrangements next to an activating gene such as NFIB66. Altered MYB has been related in the oncogenesis of both acute and chronic myeloid leukemia as well as in T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. This gene also appears amplified in esophagus, colon and breast carcinomas66. The NFIB gene (Nuclear Factor I/B, 9p24.1) codes the homonymous transcription factor, which is related to the FOXA1 transcription factor network and has been seen involved, apart from ACCs, in the genesis of pericolonic lipomas67 and more recently as a prognostic factor in osteosarcomas (when present as a germline single nucleotide pleomorphism)68 and giant cell tumors of bone69.

The importance that MYB activation, either through gene alterations or MYB-NFIB fusions, has in ACC oncogenesis has been underscored by recent whole exome sequencing studies70, 71 of head and neck ACCs, which showed an otherwise “quiet” mutational landscape with very few genetic aberrations. These findings indicate that activating MYB aberrations are likely driving these tumors14.

A series of 21 PCACC (including to periocular ACCs) recently published by North et al14, describes the presence of MYB aberrations in a subset of 10 PCACC and 1 periocular ACC that were analyzed by MYB immunohistochemistry, FISH for MYB and RT-PCR for the MYB-NFIB fusion product. Immunohistochemistry for the MYB protein was positive in all but one of the PCACC (9/10) (the periocular ACC was not studied). Regarding the FISH results, they showed that 6 of the PCACC (including the periocular ACC case) showed either MYB splits (3 PCACC and 1 periocular ACC) or deletion of the 3′ portion of the gene (2 PCACC). Detection of the MYB-NFIB fusion product by RT-PCR was attempted in 8 PCACC cases and in the periocular ACC case and showed that only 2 cases were positive, one PCACC and the periocular ACC, both of them also positive for a MYB splits on FISH. The case that was MYB-negative by immunohistochemistry was also negative for both MYB rearrangements by FISH and MYB-NFIB fusion transcript by RT-PCR and upon re-examination of the histopathology, the authors concluded that the lesion likely represents an ACC-like tumor, possibly a variant of a mixed tumor. Although FISH studies for NFIB were not carried out in this cohort, the RT-PCR data suggests that NFIB seems to be minimally involved in PCACC pathogenesis. As far as the MYB gene is concerned, it appears that a variety of aberrations play a role in its activation, including splits, loss of the 3′ portion and, judging by the widespread expression of MYB protein by immunohistochemistry, perhaps by a cryptic rearrangement that is not detected by conventional FISH, or through other mechanisms.

Our results replicate the findings by North et al with the presence of balanced MYB splits in our first 2 cases, whereas a loss of 3′ (centromeric) portion with an accompanying copy number increase of MYB was found in the third case. Since none of our cases showed NFIB abnormalities, MYB activation through MYB-NFIB fusion is unlikely. Results from both North et al and our study are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Results of MYB and NFIB FISH and MYB-NFIB RT-PCR of studies PCACC cases to date.

| MYB (FISH) | NFIB (FISH) | MYB-NFIB (RT-PCR) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| North et al Case S114 | Split signal | ND | ND |

| North et al Case S214 | Not rearranged | ND | Negative |

| North et al Case S514 | Split signal | ND | Negative |

| North et al Case S614 | Loss of 3′ portion | ND | Negative |

| North et al Case S714 | Not rearranged | ND | ND |

| North et al Case S814 | Split signal | ND | Positive |

| North et al Case S914 | Not rearranged | ND | Negative |

| North et al Case S1014 | Not rearranged | ND | Negative |

| North et al Case S1114* | Not rearranged | ND | Negative |

| North et al Case S1914 | Loss of 3′ portion | ND | Negative |

| Our Case 1 | Rearranged (balanced) (Figure 3A) | Not rearranged | ND |

| Our Case 2 | Rearranged (balanced) | Not rearranged | ND |

| Our Case 3 | Unbalanced aberration, 3 copies of MYB with deletion of centromeric (3′) portion (Figure 3B) | Not rearranged | ND |

Abbreviations: ND: No Data

Case S11 was retrospectively deemed to be a mixed tumor with ACC-like morphology

As far as the potential diagnostic utility of MYB aberrations is concerned, the status of the MYB gene in the main entities included in the differential diagnosis of PCACC is not known. There is significant morphologic as well as immunohistochemical overlap between PCACC and 3 other cutaneous entities: BCC examples with extensive adenoid change8 and the rare adnexal malignancies apocrine cribriform carcinoma (ACrC)9, A.K.A primary cutaneous cribriform carcinoma (PCCC)72, and polymorphous sweat gland carcinoma (PSGC)10. Some subtle clues help in differentiating these tumors. While all of these tumors can potentially show some degree of cribriform architecture, the presence of infiltrating borders and, especially of perineural invasion, in addition to the mucinous material and PAS-positive basement membrane material, would all favor PCACC over these entities8–10, 72. As far as the immunoprofile is concerned, PCACC is characterized by being CD117, S100 and Sox10 positive while being rimmed by p63-positive myoepithelial cells14. The absence of a S100/p63/Sox10 positive cell population will help in differentiating adenoid BCC from PCACC, while both PCACC and adenoid BCC will be positive with CD11714, 73. Likewise, while ACrC/PCCC and PSGC can show CD117 and S100 positivity, ACrC/PCCC will show no evidence of p63/Sox10 myoepithelial cells9, 72 and PSGC will show a discontinuous rimming by such cells10.

In addition to the above-described entities, some PCACC examples are known to show overlapping features with other basaloid adnexal tumors such as cylindromas and spiradenomas1. Interestingly, recent publications from Dr. Stenman’s group pointed out that a subset (8/12, 67%) of sporadic cutaneous cylindromas showed evidence of MYB–NFIB fusion and of MYB activation, detected either by FISH and/or RT-PCR of fusion transcripts as well as by MYB protein overexpression by immunohistochemistry74. In a follow up paper, they have demonstrated that cylindromas, mixed cylindromas/spiradenomas arising in individuals with germline CYLD mutations (Brooke-Spiegler syndrome) showed evidence of MYB activation, although not through the presence of MYB chromosomal aberrations or MYB-NFIB fusion, since these features were not seen in any of the tumors they studied75. It has been previously reported that Brooke-Spiegler syndrome patients also develop ACC-like basal cell carcinomas of the salivary glands76. The presence of MYB aberrations have also been described in unrelated neoplasms such as in a small subset of prostatic basal cell adenomas that show ACC-like morphology77. These results suggest that MYB aberrations apparently play not only a pivotal role in oncogenesis of these lesions, but also may contribute to the common histopathologic features among these different and seemingly unrelated tumors.

In summary, we can conclude that PCACC is a rare, low-grade malignant adnexal neoplasm with a low but significant metastatic risk. Approximately 61% of the studied cases appear to harbor MYB gene activations, either through MYB chromosomal abnormalities or, in a small fraction of cases, by generation of the MYB-NFIB fusion. When extrapolating data from ACC from other organs, this aberration appears to constitute the main genetic abnormality driving PCACCs.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors want to thank Guari Panse M.D. and Areli Karime Cuevas-Ocampo M.D. for their help in preparing this manuscript.

Grant support: P30 CA008748

Footnotes

Conflict of interests: None

Table 2. Please see supplementary materials

References

- 1.Kazakov DV, Kacerovska D, MM, McKee PH. Adenoid Cystic Carcinoma. In: Kazakov DV MM, Kacerovska D, McKee PH, editors. Cutaneous Adnexal Tumors. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2012. p. 78. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Boggio R. Letter: Adenoid cystic carcinoma of scalp. Arch Dermatol. 1975;111:793. doi: 10.1001/archderm.1975.01630180121024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stout AP, Cooley SG. Carcinoma of sweat glands. Cancer. 1951;4:521. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(195105)4:3<521::aid-cncr2820040306>3.0.co;2-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Miller WL. Sweat-gland carcinoma. A clinicopathologic problem. Am J Clin Pathol. 1967;47:767. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/47.6.767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Freeman RG, Winkelmann RK. Basal cell tumor with eccrine differentiation (eccrine epithelioma) Arch Dermatol. 1969;100:234. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cooper PH, Adelson GL, Holthaus WH. Primary cutaneous adenoid cystic carcinoma. Arch Dermatol. 1984;120:774. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dores GM, Huycke MM, Devesa SS, Garcia CA. Primary cutaneous adenoid cystic carcinoma in the United States: incidence, survival, and associated cancers, 1976 to 2005. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;63:71. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2009.07.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Saxena K, Manohar V, Bhakhar V, Bahl S. Adenoid basal cell carcinoma: a rare facet of basal cell carcinoma. BMJ Case Rep. 2016;2016 doi: 10.1136/bcr-2015-214166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rutten A, Kutzner H, Mentzel T, et al. Primary cutaneous cribriform apocrine carcinoma: a clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical study of 26 cases of an under-recognized cutaneous adnexal neoplasm. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;61:644. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2009.03.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Walker A, Mesinkovska NA, Emanuel PO, Vidimos A, Billings SD. Polymorphous sweat gland carcinoma: a report of two cases. J Cutan Pathol. 2016;43:594. doi: 10.1111/cup.12695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stenman G, Dahlenfors R, Mark J, Sandberg N. Adenoid cystic carcinoma: a third type of human salivary gland neoplasms characterized cytogenetically by reciprocal translocations. Anticancer Res. 1982;2:11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nordkvist A, Mark J, Gustafsson H, Bang G, Stenman G. Non-random chromosome rearrangements in adenoid cystic carcinoma of the salivary glands. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 1994;10:115. doi: 10.1002/gcc.2870100206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Persson M, Andren Y, Mark J, Horlings HM, Persson F, Stenman G. Recurrent fusion of MYB and NFIB transcription factor genes in carcinomas of the breast and head and neck. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:18740. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0909114106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.North JP, McCalmont TH, Fehr A, van Zante A, Stenman G, LeBoit PE. Detection of MYB Alterations and Other Immunohistochemical Markers in Primary Cutaneous Adenoid Cystic Carcinoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 2015 doi: 10.1097/PAS.0000000000000463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sanderson KV, Batten JC. Adenoid cystic carcinoma of the scalp with pulmonary metastasis. Proc R Soc Med. 1975;68:649. doi: 10.1177/003591577506801021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dissanayake RV, Salm R. Sweat-gland carcinomas: prognosis related to histological type. Histopathology. 1980;4:445. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.1980.tb02939.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Boggio RR. Primary adenoid cystic carcinoma of the skin. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1985;109:707. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lang PG, Jr, Metcalf JS, Maize JC. Recurrent adenoid cystic carcinoma of the skin managed by microscopically controlled surgery (Mohs surgery) J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 1986;12:395. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.1986.tb01925.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wick MR, Swanson PE. Primary adenoid cystic carcinoma of the skin. A clinical, histological, and immunocytochemical comparison with adenoid cystic carcinoma of salivary glands and adenoid basal cell carcinoma. Am J Dermatopathol. 1986;8:2. doi: 10.1097/00000372-198602000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Meyrick Thomas RH, Lowe DG, Munro DD. Primary adenoid cystic carcinoma of the skin. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1987;12:378. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2230.1987.tb02516.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.van der Kwast TH, Vuzevski VD, Ramaekers F, Bousema MT, Van Joost T. Primary cutaneous adenoid cystic carcinoma: case report, immunohistochemistry, and review of the literature. Br J Dermatol. 1988;118:567. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1988.tb02469.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ikegawa S, Saida T, Obayashi H, et al. Cisplatin combination chemotherapy in squamous cell carcinoma and adenoid cystic carcinoma of the skin. J Dermatol. 1989;16:227. doi: 10.1111/j.1346-8138.1989.tb01254.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fukai K, Ishii M, Kobayashi H, et al. Primary cutaneous adenoid cystic carcinoma: ultrastructural study and immunolocalization of types I, III, IV, V collagens and laminin. J Cutan Pathol. 1990;17:374. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0560.1990.tb00115.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kuramoto Y, Tagami H. Primary adenoid cystic carcinoma masquerading as syringoma of the scalp. Am J Dermatopathol. 1990;12:169. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bergman R, Lichtig C, Moscona RA, Friedman-Birnbaum R. A comparative immunohistochemical study of adenoid cystic carcinoma of the skin and salivary glands. Am J Dermatopathol. 1991;13:162. doi: 10.1097/00000372-199104000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Salzman MJ, Eades E. Primary cutaneous adenoid cystic carcinoma: a case report and review of the literature. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1991;88:140. doi: 10.1097/00006534-199107000-00025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chesser RS, Bertler DE, Fitzpatrick JE, Mellette JR. Primary cutaneous adenoid cystic carcinoma treated with Mohs micrographic surgery toluidine blue technique. J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 1992;18:175. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.1992.tb02794.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Matsumura T, Kumakiri M, Ohkawara A, Yoshida T. Adenoid cystic carcinoma of the skin–an immunohistochemical and ultrastructural study. J Dermatol. 1993;20:164. doi: 10.1111/j.1346-8138.1993.tb03852.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yoshihara T, Ikuta H, Hibi S, Todo S, Imashuku S. Second cutaneous neoplasms after acute lymphoblastic leukemia in childhood. Int J Hematol. 1993;59:67. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Irvine AD, Kenny B, Walsh MY, Burrows D. Primary cutaneous adenoid cystic carcinoma. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1996;21:249. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2230.1996.tb00085.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kato N, Yasukawa K, Onozuka T. Primary cutaneous adenoid cystic carcinoma with lymph node metastasis. Am J Dermatopathol. 1998;20:571. doi: 10.1097/00000372-199812000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zimmerman RL, Bibbo M. Fine needle aspiration diagnosis of a pulmonary metastasis from a cutaneous adenoid cystic carcinoma. A case report. Acta Cytol. 1998;42:367. doi: 10.1159/000331617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chang SE, Ahn SJ, Choi JH, Sung KJ, Moon KC, Koh JK. Primary adenoid cystic carcinoma of skin with lung metastasis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;40:640. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(99)70454-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gelabert-Gonzalez M, Febles-Perez C, Martinez-Rumbo R. Spinal cord compression caused by adjacent adenocystic carcinoma of the skin. Br J Neurosurg. 1999;13:601. doi: 10.1080/02688699943141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Weekly M, Lydiatt DD, Lydiatt WM, Baker SC, Johansson SL. Primary cutaneous adenoid cystic carcinoma metastatic to cervical lymph nodes. Head Neck. 2000;22:84. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0347(200001)22:1<84::aid-hed12>3.0.co;2-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Koh BK, Choi JM, Yi JY, Park CJ, Lee HW, Kang SH. Recurrent primary cutaneous adenoid cystic carcinoma of the scrotum. Int J Dermatol. 2001;40:724. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-4362.2001.01281-3.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Krunic AL, Kim S, Medenica M, Laumann AE, Soltani K, Shaw JC. Recurrent adenoid cystic carcinoma of the scalp treated with mohs micrographic surgery. Dermatol Surg. 2003;29:647. doi: 10.1046/j.1524-4725.2003.29155.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Doganay L, Bilgi S, Aygit C, Altaner S. Primary cutaneous adenoid cystic carcinoma with lung and lymph node metastases. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2004;18:383. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2004.00904.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Duzova AN, Boztepe G, Sahin S, Gokoz A. Painful nodule on the scalp: a case of primary cutaneous adenoid cystic carcinoma. Acta Derm Venereol. 2004;84:243. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fueston JC, Gloster HM, Mutasim DF. Primary cutaneous adenoid cystic carcinoma: a case report and literature review. Cutis. 2006;77:157. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Barnes J, Garcia C. Primary cutaneous adenoid cystic carcinoma: a case report and review of the literature. Cutis. 2008;81:243. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Benchetritt M, Butori C, Long E, Ilie M, Ferrari E, Hofman P. Pericardial effusion as primary manifestation of metastatic cutaneous adenoid cystic carcinoma: diagnostic cytopathology from an exfoliative sample. Diagn Cytopathol. 2008;36:351. doi: 10.1002/dc.20818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Numajiri T, Nishino K, Uenaka M. Giant primary cutaneous adenoid cystic carcinoma of the perineum: histological and radiological correlations. Acta Derm Venereol. 2008;88:316. doi: 10.2340/00015555-0430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cansu DU, Kasifoglu T, Ackaln M, Korkmaz C. The development of primary cutaneous adenoid cystic carcinoma in a patient with ankylosing spondylitis treated with etanercept. South Med J. 2009;102:738. doi: 10.1097/SMJ.0b013e3181a7fb33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Singh A, Ramesh V. Primary cutaneous adenoid cystic carcinoma with distant metastasis: a case report and brief literature review. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2010;76:176. doi: 10.4103/0378-6323.60573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Torres T, Caetano M, Alves R, Horta M, Selores M. Tender tumor of the scalp: clinicopathologic challenge. Primary cutaneous adenoid cystic carcinoma. Int J Dermatol. 2010;49:605. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2009.04426.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Xia Y, Xu S, Liu X, Chen AC. Photodynamic therapy as consolidation treatment for primary cutaneous adenoid cystic carcinoma: a case report. Photomed Laser Surg. 2010;28:707. doi: 10.1089/pho.2009.2663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Xu YG, Hinshaw M, Longley BJ, Ilyas H, Snow SN. Cutaneous adenoid cystic carcinoma with perineural invasion treated by mohs micrographic surgery-a case report with literature review. J Oncol. 2010;2010:469049. doi: 10.1155/2010/469049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cacchi C, Persechino S, Fidanza L, Bartolazzi A. A primary cutaneous adenoid-cystic carcinoma in a young woman. Differential diagnosis and clinical implications. Rare Tumors. 2011;3:e3. doi: 10.4081/rt.2011.e3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Raychaudhuri S, Santosh KV, Satish Babu HV. Primary cutaneous adenoid cystic carcinoma of the chest wall: a rare entity. J Cancer Res Ther. 2012;8:633. doi: 10.4103/0973-1482.106583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lestouquet FR, Sanchez Moya AI, Guerra SH, Cardona Alzate CJ. Primary cutaneous adenoid cystic carcinoma: an unusual case. Dermatol Online J. 2013;19:5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Maybury CM, Patel K, Attard N, Robson A. A nodule in the groin. Primary cutaneous adenoid cystic carcinoma (pcACC) JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149:1343. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2013.4358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Morrison AO, Gardner JM, Goldsmith SM, Parker DC. Primary cutaneous adenoid cystic carcinoma of the scalp with p16 expression: a case report and review of the literature. Am J Dermatopathol. 2014;36:e163. doi: 10.1097/DAD.0000000000000094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Rocas D, Asvesti C, Tsega A, Katafygiotis P, Kanitakis J. Primary adenoid cystic carcinoma of the skin metastatic to the lymph nodes: immunohistochemical study of a new case and literature review. Am J Dermatopathol. 2014;36:223. doi: 10.1097/DAD.0b013e31829ae1e7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Matsumoto N, Hata Y, Tanese K. Case of primary cutaneous adenoid cystic carcinoma: Expression of c-KIT and activation of its downstream signaling molecules. J Dermatol. 2015;42:1109. doi: 10.1111/1346-8138.13054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Mertens RB, de Peralta-Venturina MN, Balzer BL, Frishberg DP. GATA3 Expression in Normal Skin and in Benign and Malignant Epidermal and Cutaneous Adnexal Neoplasms. Am J Dermatopathol. 2015;37:885. doi: 10.1097/DAD.0000000000000306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Nakajima H, Matsushima T, Sano S. Primary cutaneous adenoid cystic carcinoma arising from folliculitis decalvans. J Dermatol. 2015;42:741. doi: 10.1111/1346-8138.12880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Pozzobon LD, Glikstein R, Laurie SA, et al. Primary cutaneous adenoid cystic carcinoma with brain metastases: case report and literature review. J Cutan Pathol. 2015 doi: 10.1111/cup.12563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lee SJ, Yang WI, Kim SK. Primary Cutaneous Adenoid Cystic Carcinoma Arising in Umbilicus. J Pathol Transl Med. 2016 doi: 10.4132/jptm.2015.11.24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Pohl U, Said I, Low HL. Rare delayed brain metastasis from primary cutaneous adenoid cystic carcinoma. Clin Neuropathol. 2016;35:39. doi: 10.5414/NP300880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Headington JT, Teears R, Niederhuber JE, Slinger RP. Primary adenoid cystic carcinoma of skin. Arch Dermatol. 1978;114:421. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Naylor E, Sarkar P, Perlis CS, Giri D, Gnepp DR, Robinson-Bostom L. Primary cutaneous adenoid cystic carcinoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;58:636. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2007.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Seab JA, Graham JH. Primary cutaneous adenoid cystic carcinoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1987;17:113. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(87)70182-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Urso C, Bondi R, Paglierani M, Salvadori A, Anichini C, Giannini A. Carcinomas of sweat glands: report of 60 cases. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2001;125:498. doi: 10.5858/2001-125-0498-COSG. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ramakrishnan R, Chaudhry IH, Ramdial P, et al. Primary cutaneous adenoid cystic carcinoma: a clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical study of 27 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2013;37:1603. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e318299fcac. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ramsay RG, Gonda TJ. MYB function in normal and cancer cells. Nat Rev Cancer. 2008;8:523. doi: 10.1038/nrc2439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Italiano A, Ebran N, Attias R, et al. NFIB rearrangement in superficial, retroperitoneal, and colonic lipomas with aberrations involving chromosome band 9p22. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2008;47:971. doi: 10.1002/gcc.20602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Mirabello L, Koster R, Moriarity BS, et al. A Genome-Wide Scan Identifies Variants in NFIB Associated with Metastasis in Patients with Osteosarcoma. Cancer Discov. 2015;5:920. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-15-0125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Quattrini I, Pollino S, Pazzaglia L, et al. Prognostic role of nuclear factor/IB and bone remodeling proteins in metastatic giant cell tumor of bone: A retrospective study. J Orthop Res. 2015;33:1205. doi: 10.1002/jor.22873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Costa AF, Altemani A, Garcia-Inclan C, et al. Analysis of MYB oncogene in transformed adenoid cystic carcinomas reveals distinct pathways of tumor progression. Lab Invest. 2014;94:692. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.2014.59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Ho AS, Kannan K, Roy DM, et al. The mutational landscape of adenoid cystic carcinoma. Nat Genet. 2013;45:791. doi: 10.1038/ng.2643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Arps DP, Chan MP, Patel RM, Andea AA. Primary cutaneous cribriform carcinoma: report of six cases with clinicopathologic data and immunohistochemical profile. J Cutan Pathol. 2015;42:379. doi: 10.1111/cup.12469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Terada T. Expression of NCAM (CD56), chromogranin A, synaptophysin, c-KIT (CD117) and PDGFRA in normal non-neoplastic skin and basal cell carcinoma: an immunohistochemical study of 66 consecutive cases. Med Oncol. 2013;30:444. doi: 10.1007/s12032-012-0444-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Fehr A, Kovacs A, Loning T, Frierson H, Jr, van den Oord J, Stenman G. The MYB-NFIB gene fusion-a novel genetic link between adenoid cystic carcinoma and dermal cylindroma. J Pathol. 2011;224:322. doi: 10.1002/path.2909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Rajan N, Andersson MK, Sinclair N, et al. Overexpression of MYB drives proliferation of CYLD-defective cylindroma cells. J Pathol. 2016;239:197. doi: 10.1002/path.4717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Antonescu CR, Terzakis JA. Multiple malignant cylindromas of skin in association with basal cell adenocarcinoma with adenoid cystic features of minor salivary gland. J Cutan Pathol. 1997;24:449. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0560.1997.tb00822.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Bishop JA, Yonescu R, Epstein JI, Westra WH. A subset of prostatic basal cell carcinomas harbor the MYB rearrangement of adenoid cystic carcinoma. Hum Pathol. 2015;46:1204. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2015.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.