Abstract

With menopause, circulating levels of 17β-estradiol (E2) markedly decrease. E2-based hormone therapy is prescribed to alleviate symptoms associated with menopause. E2 is also recognized for its beneficial effects in the central nervous system (CNS), such as enhanced cognitive function following abrupt hormonal loss associated with ovariectomy. For women with an intact uterus, an opposing progestogen component is required to decrease the risk of developing endometrial hyperplasia. While adding an opposing progestogen attenuates these detrimental effects on the uterus, it can attenuate the beneficial effects of E2 in the CNS. Poly (lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA) micro- and nano- carriers (MNCs) have been heavily investigated for their ability to enhance the therapeutic activity of hydrophobic agents following exogenous administration, including E2. Multiple PLGA MNC formulation parameters, such as composition, molecular weight, and type of solvent used, can be altered to systematically manipulate the pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic profiles of encapsulated agents. Thus, there is an opportunity to enhance the therapeutic activity of E2 in the CNS through controlled delivery from PLGA MNCs. The aim of this review is to consider the fate of exogenously administered E2 and discuss how PLGA MNCs and route of administration can be used as strategies for controlled E2 delivery.

Key terms: (3–10): 17β-estradiol, E2, PLGA, microparticle, nanoparticle, drug delivery, polymer, cognition

Introduction

17β-estradiol (E2) is the most potent naturally circulating estrogen in some mammals. E2 is vital for the healthy development and maintenance of female reproductive tissues, as well as for the regulation of the female reproductive cycle. In women, the circulating levels of E2 range from 40 pg/ml to 250 pg/ml across a normal menstrual cycle46. However, following the onset of reproductive senescence (menopause) in women, E2 blood serum levels drop to below 15 pg/ml46. At menopause, there is a lack of ovarian follicles available for maturation and subsequent ovulation, thus resulting in a drastic decrease in circulating levels of ovarian hormones secreted during a normal menstrual cycle (i.e. estrogens and progesterone)54 Menopause occurs at the average age of 51 and is associated with undesired physiological symptoms (i.e. hot flashes, vaginal atrophy, and osteoporosis) that vary among women in presence and severity. As a result, numerous hormone therapy options were designed for treatments that differ as a function of hormone type, hormone combination ratios, and route of administration. E2-based hormone therapy has been approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for alleviating symptoms associated with menopause74. However, E2 exposure is associated with an increase in the risk for developing endometrial hyperplasia and must be accompanied by an opposing progestogen component, suggesting that there is opportunity for significant enhancement for E2-based hormone therapy59.

In addition to its well-known role in female endocrinology, E2 is also recognized for its more broad neuroprotective effects, which suggests that hormone therapy could be of interest for treating conditions other than symptoms associated with menopause8,27,33 For example, E2 has been shown to enhance normal cognitive function following the loss of circulating ovarian hormones, in both humans and in animal models41,50,53. E2 has also been examined as a potential therapeutic treatment for neurodegenerative diseases, such as Alzheimer’s disease (AD)3,4,16,38,76,84. However, there is evidence that both natural progesterone and synthetic progestogens, such as medroxyprogesterone acetate, can offset the beneficial effects of E2 on cognitive function7,32,33,48. Moreover, studies have shown that the addition of progesterone attenuated E2-induced increase in the activation of extracellular signal-regulated kinase 2 (Erk2) in the dorsal hippocampus; of note, there is evidence that this activation is sufficient for E2 to produce beneficial cognitive effects10,27,33,83. Additional research has demonstrated that an E2-induced increase in the expression of several neurotrophin factors (i.e. brain-derived neurotrophic factor, nerve growth factor) in the CNS is attenuated by the addition of a progestogen component8.

Taking current knowledge in sum, E2 is of therapeutic interest in both menopause as well as diseases affecting the CNS, but the required addition of an opposing progestogen to E2 therapy can limit or inhibit the beneficial role of E2 in CNS function. Altering the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of exogenously administered E2 may enhance the therapeutic potential of E2, with the overarching goal to maximize its beneficial effects on the CNS, while minimizing its detrimental effects on tissues such as the uterus. Thus, the objective of this review is to address the fate of exogenously administered E2 and to query whether its pharmacokinetic or pharmacodynamic profiles can be altered, either through route of administration or the use of synthetic micro- and nano- carriers (MNCs). We propose that these approaches will provide new avenues for hormone therapy in menopause as well as for novel CNS-targeted treatment of cognitive function or other CNS-related diseases (e.g., AD).

The fate of exogenously administered E2

Clinically, E2 is often administered via oral or transdermal routes, and was previously available for administration via the intranasal route. Systemically circulating E2 is typically bound to sex hormone binding globulin and to albumin, resulting in only ~1–2% of the total circulating E2 available for activity1,43. The average half-life of circulating E2 is ~2.7 hours following transdermal E2 patch administration, and ~30 minutes following intravenous E2 administration, in postmenopausal women; E2 is cleared through urine and fecal matter29,77. E2 reaches multiple target tissues in the body, including the brain, liver, uterus, bone, and adipose tissue. Oral and intranasal administration produces delivery of E2 in a cyclic fashion, as the treatment is typically taken once daily, resulting in cyclic concentrations of circulating E2. Oral administration of E2 leads to immediate first-pass metabolism of E2, thus requiring high doses (~1–2 mg E2 /day) to obtain the desired effects of E2-based hormone therapy. Orally administered E2 is rapidly converted by the gut wall and liver into the less potent estrogen metabolites estrone (E1) and, to a lesser extent, estriol, as well as estrogen conjugates such as E2-glucuronide, E1-glucuronide, and E1-sulfate43,66. Next, E2 either enters the bile pool for enterohepatic circulation or the bloodstream. High intra- and inter- patient differences in circulating levels of E2 following oral administration are expected due to individual differences in metabolism44.

The intranasal route of administration allows for large surface absorption of E2 and avoids first-pass metabolism. Devissaguet et al. (1999) showed that with intranasal delivery, the maximum concentration of E2 in the blood plasma was reached within the first 10-30 minutes, after which E2 concentration rapidly fell, returning to the same level as untreated postmenopausal women within 12 hours of administration20. Intranasal administration has the potential advantage of improving brain-specific exposure to E2, although E2 must be appropriately solubilized for delivery via this route. For example, a previously clinically-available intranasal E2 hormone therapy, Aerodiol™, was composed of solubilized E2 in randomly methylated β-cyclodextrin. Clinical evaluations of Aerodiol™ in postmenopausal women resulted in significant improvement of symptoms associated with menopause, as measured by the Kupperman Index and the number of hot flashes reported64. Additionally, a randomized dose-response clinical study for Aerodiol™ demonstrated that similar E2 blood serum levels were achieved after 12 weeks of Aerodiol™ treatment with the lowest effective dose (200 μg E2 /day in postmenopausal women) compared to women who received orally administered E2 doses of 1 mg and 2 mg. Interestingly, blood serum E1 levels following 1 mg and 2 mg of E2 oral administration were at least 5-fold greater than that of the 200 μg E2 /day intranasal administration of Aerodiol™, in postmenopausal women69. This may be, in part, explained by the rapid first-pass metabolism of E2 to E1 following oral administration that is circumvented by the intranasal route of administration.

With the transdermal route, E2 is applied to the skin via a patch or gel, which allows for a relatively sustained presence of E2 in circulation and tissues. Once applied, E2 must diffuse through the stratum corneum, epidermis, and dermis before entering the circulation43. In this manner, the transdermal route of administration avoids first-pass metabolism of E2 that is expected with the oral route. Large inter- and intra-patient differences in circulating E2 concentrations have been reported with transdermal E2, most likely due to individual differences in the rate of absorption of E2 across the skin layers and into the bloodstream43. Additionally, it is important to note that the transdermal application of E2 can result in mild to moderate adverse skin reactions, such as skin erythema13. At least a 2–10 mg dose of E2 is required to obtain a passage of ~50 μg E2 across the skin layers and into the bloodstream65. To aid in absorption of E2, micellar nanoparticles have been successfully utilized and clinically approved for use in transdermal E2-based hormone therapy (Estrasorb™) to alleviate severe vasomotor symptoms associated with menopause75. Thus, the route of administration heavily dictates the fate of exogenously administered E2. Moreover, there is precedent for clinically approved use of drug carriers (cyclodextrins, micellar nanoparticles) to enhance the effectiveness of E2-based hormone therapy in treatment of symptoms associated with menopause.

E2 encapsulation in PLGA micro- and nano- carriers (MNCs)

Although clinically available E2-based hormone therapies are considered both safe and effective, there are still significant opportunities for improvement. First, off-target tissue delivery poses a long-term risk for endometrial hyperplasia development59. These risks can be mitigated by treating with an opposing progestogen; however, progestogens can also reduce some of the beneficial aspects of E2 treatment59. For instance, the addition of progestogens have been shown to attenuate the beneficial effects of E2 on cognitive function as well as E2-induced increases in protein expression/activation (i.e. brain-derived neurotrophic factor, nerve growth factor, Erk2)7,8,32,48. Second, E2 is under investigation, but has not been clinically approved, for other indications; development of novel E2 therapeutics, particularly those that selectively deliver E2 to the CNS, could open new treatment opportunities for diseases such as AD3,4,16,38,76,84 Third, rapid clearance and metabolism of exogenously administered E2 remains a bottleneck for efficient E2 treatment, particularly when delivery to low concentration sites, such as the CNS, is needed.

Here, we turn our attention to summarizing how MNCs could be used to enhance therapeutic potential of E2 in diseases affecting the CNS. We will focus specifically on manipulating the pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic profile of E2 through encapsulation in MNCs composed of poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA)11,14,15,31,45. PLGA is a member of the biodegradable and biocompatible polyester family of polymers. PLGA MNCs have long been of interest for drug delivery purposes, being considered to be of generally low toxicity, possessing high capacity for drug loading, and having potential for a range of rates of degradation and drug release2,15,18. Encapsulated drugs are released from PLGA MNCs in three stages: first, surface associated drug is released rapidly in a “burst” fashion; second, bulk sustained release is achieved through diffusion of the drug either through the polymer or through water filled pores, and, third, bulk degradation eventually leads to complete disintegration of the MNC, resulting in a final burst release22,28. Drug activity is often preserved or enhanced through encapsulation, by protection and slow release in physiological environments. Additionally, one intriguing opportunity for PLGA MNCs is the ease with which their size, charge, or surface properties can be engineered to facilitate interaction of the MNC with specific cells or tissues42.

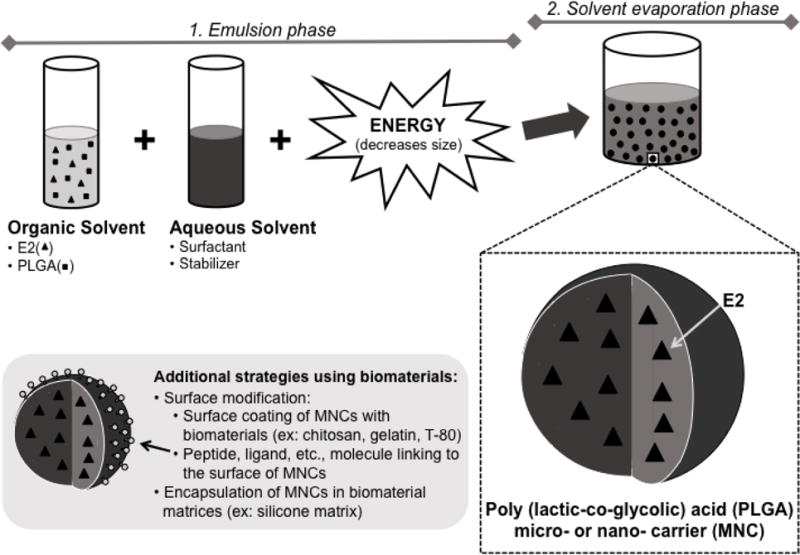

PLGA MNCs are fabricated through a variety of approaches, which have been extensively covered in several review and methodology papers. The most commonly used technique, termed emulsion/solvent evaporation, involves dissolving the polymer with drug in an organic solvent, which is added to an aqueous phase containing emulsifying/stabilizing agents or other solvents; high frequency energy may be introduced to facilitate formation of small polymer droplets (see Figure 1)22,37,39,52,62. Solvent may then be extracted, and the resultant hardened MNCs are collected and either stored frozen in water or lyophilized. Alternatively, a technique termed nanoprecipitation involves selection of water miscible solvents, and the polymer solution is dropped directly into an aqueous phase, whereby particles form spontaneously5,17,39,68. Another technique, electrospraying, involves the use of electrohydrodynamic processing to break apart the polymer-containing solution, resulting in formation of PLGA MNCs23–25,30,79. Varying specific parameters, such as type of polymer, surfactant, or organic solvent, can be used as strategies for altering the particle size, encapsulation efficiency (EE), and release profile; we will discuss these strategies below (Tables 1 and 2).

Figure 1. One common method for fabricating PLGA MNCs is emulsion/solvent evaporation.

To form E2 loaded MNCs by emulsion, E2 and PLGA are dissolved in an organic solvent or mixture of solvents. The drug/polymer solution (oil phase) is added to an aqueous phase containing stabilizing or emulsifying agents and mixed to produce droplets; high frequency energy may be introduced to facilitate the formation of smaller diameter MNCs (i.e., nanoparticles). This emulsion is added to a larger aqueous volume, and the organic solvent is allowed to evaporate under stirring or vacuum to harden MNCs. By manipulating formulation parameters, MNCs can be engineered for specific properties — for example, to improve drug loading, prolong release, or promote interaction of MNCs with specific tissues or cells. Alternative methods for preparing MNCs (e.g., nanoprecipitation) as well as specific approaches to achieve surface modification of MNCs are discussed in detail elsewhere39.

Table 1.

Summary of PLGA characteristics, type of surfactant, and type of organic solvent influence on E2 encapsulation efficiency (EE) in PLGA MNCs.

| Parameter | Author | Comparison | Highest E2 EE |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Lactide to glycolide ratio | Irmak et al., 2014 | 50:50, 65:35 PLGA | 65:35 PLGA (54% E2 EE) |

| Zaghloul et al., 2005 | PLA, 85:15 PLGA, 75:25 PLGA, and a mixture of the polymers | High E2 EE for all formulations (> 80% E2 EE) | |

|

| |||

| Surfactant | Sahana et al., 2007 | DMAB, PVA | PVA (> 48% E2 EE) |

| Hariharan et al., 2006 | DMAB, PVA | DMAB (57–73% E2 EE) | |

| Xinteng et al., 2002 | varying PVA concentrations | Decreasing PVA (87% E2 EE with lowest PVA concentration) | |

| Zaghloul 2006 | PVA, T-80, SLS, and benzalkonium chloride | PVA (99% E2 EE) | |

|

| |||

| Organic Solvent | Sahana et al., 2007 | EA, acetone, chloroform, DCM | DCM and EA combination (> 43% E2 EE) |

| Birnbaum et al., 2000 | DCM, EA, DCM and methanol (90:10) combination methanol and DCM | High E2 EE for all formulations (> 90% E2 EE) | |

| Hong et al., 2011 | (1:2, 1:4) combinations and EA and DCM (1:1, 1:1.5) combinations | High E2 EE for all formulations (>75% E2 EE) | |

| Zaghloul 2006 | EA, acetone, DCM, THF, chloroform | EA (97% E2 EE) | |

Abbreviations: polyvinyl alcohol (PVA), didodecyldimethyl ammonium bromide (DMAB), Tween-80 (T-80), sodium lauryl sulfate (SLS), benzalkonium chloride, acetone, ethyl acetate (EA), chloroform, dichloromethane (DCM), methanol, and tetrahydrofuran (THF).

Table 2.

Summary of PLGA characteristics, type of surfactant, and type of organic solvent influence on E2 release from PLGA MNCs.

| Parameter | Author | Comparison | Result | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Lactide to glycolide ratio | Mittal et al., 2007 | 50:50, 65:35, 85:15 PLGA | E2 release decreased as lactide to glycolide ratio increased | |

| Brannon-Peppas, 1994 | 50:50, 65:35, 75:25 PLGA | Rapid E2 release for all formulations | ||

|

| ||||

| Molecular weight | Mittal et al., 2007 | 14,500–213,000 Da PLGA | E2 release decreased as molecular weight increased | |

|

| ||||

| Surfactant | Sahana et al., 2007 | DMAB, PVA | Slower E2 release with PVA vs. DMAB in vitro; slower E2 release with DMAB vs PVA in vivo (oral admin.) | |

| Hariharan et al., 2006 | DMAB, PVA | Slower E2 release with PVA vs. DMAB in vitro; slower E2 release with DMAB vs PVA in vivo (oral admin.) | ||

| Zaghloul 2006 | PVA, T-80, SLS, and benzalkonium chloride | Slowest E2 release with PVA, followed by benzalkonium chloride, SLS, and fastest with T-80 | ||

|

| ||||

| Organic Solvent | Sahana et al., 2007 | EA, acetone, chloroform, and DCM | Slowest E2 release with EA, and greatest E2 release per day with EA and DCM combination | |

| Birnbaum et al., 2000 | DCM; EA; DCM and methanol (90:10) combination methanol and DCM | Slower and more constant E2 release with EA and with DCM and methanol (90:10) combination compared to DCM | ||

| Hong et al., 2011 | (1:2, 1:4) combinations and EA and DCM (1:1, 1:1.5) combinations | Slowest E2 release with 1:1.5 EA to DCM ratio | ||

| Zaghloul 2006 | EA, acetone, DCM, THF, chloroform | Slowest E2 release with EA, followed by acetone, DCM, THF, and fastest with chloroform | ||

|

| ||||

| Particle size | Enayati et al., 2012 | 100–4500 nm in diameter | Decreased burst and slower initial E2 release as particle size increased | |

Abbreviations: polyvinyl alcohol (PVA), didodecyldimethyl ammonium bromide (DMAB), Tween-80 (T-80), sodium lauryl sulfate (SLS), benzalkonium chloride, acetone, ethyl acetate (EA), chloroform, dichloromethane (DCM), methanol, and tetrahydrofuran (THF).

PLGA characteristics

The molecular weight and the lactide to glycolide ratio of PLGA MNCs can be altered to adjust the rate of particle degradation, with lower glycolide content and higher molecular weight resulting in a decreased rate of degradation15,78. In one study, PLGA nanoparticles were synthesized using 50:50, 65:35, or 85:15 PLGA to investigate whether varying the lactide to glycolide ratio will impact the release profile of E258. Results indicated that increasing the lactide to glycolide content decreased the release of E2 from PLGA nanoparticles58. In the same study, increasing the molecular weight of 50:50 PLGA from 14,500—213,000 Da decreased E2 release from the nanoparticles58. Analysis of E2 levels in the blood plasma following oral administration of E2 PLGA replicated these results, showing that increased molecular weight of the polymer and an increased lactide to glycolide ratio sustained the release of E2 from PLGA nanoparticles in blood plasma58. On the other hand, a study that compared a 50:50, 65:35, and 75:25 lactide to glycolide ratio of PLGA microparticles found that all three formulations exhibited quick E2 release, with greater than 70% of E2 released within the first 24 hours12. In terms of E2 EE, a comparison of 50:50 and 65:35 PLGA showed a 30% E2 EE for 50:50 PLGA nanoparticles, and a 54% E2 EE for 65:35 PLGA nanoparticles36. Taken together, these studies suggest that increasing the ratio of lactide to glycolide in PLGA-based nanoparticles and increasing the molecular weight of the polymer can be potentially utilized to modestly improve sustained release of E2. Moreover, an increased lactide to glycolide ratio can increase E2 EE.

A study that examined polylactic acid (PLA), 85:15 PLGA, 75:25 PLGA, and a mixture of the polymers, as well as 1:3, 1:5, and 1:7 E2 to polymer ratio for each microparticle formulation showed that E2 EE in all cases was greater than 80% E2 EE82. Interestingly, the 1:5 E2 to polymer ratio resulted in the highest E2 EE compared to 1:3 and 1:7 E2 to polymer ratios for all polymer formulations except for PLA based microparticles82. The slowest cumulative release of E2 was seen when the polymer concentration was low (1:3 E2 to polymer ratio) for all four types of polymer formulations82. When PLA particles were examined for E2 EE with 1:20, 1:16, 1:13, and 1:10 E2 to PLA ratios, the 1:16 E2 to PLA formulation resulted in the highest E2 EE (72% of total E2) compared to 1:20, 1:13, and 1:10 E2 to PLA formulations. E2 EE decreased as the ratio of E2 to PLA increased, with the lowest E2 EE seen with 1:10 E2 to PLA (56% of total E2). Thus, the ratio of E2 to polymer during synthesis can influence the E2 EE as well as the release profile of E2, with lower polymer concentration resulting in slower E2 release.

Surfactant

Several different emulsifiers have been used for generating E2 loaded PLGA MNCs, including polyvinyl alcohol (PVA), didodecyldimethyl ammonium bromide (DMAB), Tween-80 (T-80), sodium lauryl sulfate (SLS), and benzalkonium chloride. One study examined the effect of PVA versus DMAB on PLGA particle size and E2 EE. The results showed that smaller particle size was seen with DMAB whereas higher E2 EE was seen with PVA as the surfactants67. Additionally, the slowest release profile of E2, lasting 54 days, was seen with nanoparticles made using PVA67. Following oral administration, nanoparticles made with DMAB released E2 for at least 5 days, possibly due to smaller particle size, whereas nanoparticles made with PVA released E2 within 3 days67. Another study examining DMAB versus PVA as the surfactants replicated most of these results, showing that using DMAB results in smaller sized particles compared to PVA34 In this same study, PLGA nanoparticles made with PVA had a longer E2 release period, lasting over 45 days, compared to PLGA nanoparticles made with DMAB, which had an E2 release period of 31 days34 Following oral administration, PLGA particles made with DMAB released over a period of 7 days but PLGA particles made with PVA released over a period of 2 days34 However, E2 EE was lower with PVA as the surfactant, ranging from 47–62% E2 EE with PVA and from 57–73% E2 EE with DMAB34 Interestingly, another study showed that increasing the concentration of PVA used in the synthesis decreased E2 EE80. Another study tested the difference between using PVA, T-80, SLS, and benzalkonium chloride on E2 EE and E2 release from PLGA microparticles that were made with a mixture of PLA and 85:15 PLGA polymers. Although all surfactants resulted in E2 EE greater than 85%, PVA had the highest E2 EE of 99%81. PVA also resulted in the slowest E2 release, with only 47% of E2 released after 120 hours compared to 90%, 77%, and 63% with T-80, SLS, and benzalkonium chloride, respectively81. Results from these studies evaluating the effect of surfactant type on E2 PLGA formulations suggest that in most cases the optimal formulation, where E2 EE is highest and E2 burst release is lowest, is produced when PVA is used as the surfactant.

Organic solvent

Common organic solvents used in PLGA MNCs synthesis include acetone, ethyl acetate (EA), chloroform, dichloromethane (DCM), methanol, and tetrahydrofuran (THF). A study examining the effect of EA, acetone, chloroform, and DCM on E2 EE and E2 release from nanoparticles revealed that there is a similar E2 release profile for all 50:50 PLGA nanoparticle formulations67. However, the greatest average release per day was seen when using a combination of DCM and EA as the organic solvent67. This effect is most likely due to a higher E2 EE achieved when using this particular organic solvent combination67. The same study showed that using EA as the organic solvent resulted in the slowest release of E2, which lasted over 54 days67. Another study investigated DCM, EA, or a combination of DCM with methanol (90:10) as organic solvents used in 50:50 PLGA microparticle syntheses, resulting in high E2 EE that was greater than 90% for most particle formulations9. EA and the DCM with methanol (90:10) combination as the organic solvents produced a more constant E2 release profile from the microparticles, with 25% of E2 released within the first 24hrs, relative to DCM alone as the organic solvent, with 65% of E2 released within the first 24hrs9. A comparison between either methanol to DCM ratio (1:2, 1:4) or EA to DCM ratio (1:1, 1:1.5) as organic solvents for synthesis of 85:15 PLGA microparticles showed that E2 EE for all formulations was greater than 75%35. The 1:1.5 EA to DCM ratio for organic solvent resulted in only 55% of E2 released from the PLGA microparticle within the first 24 hours, but both methanol to DCM formulations resulted in 100% cumulative release within 24 hours35. Another study investigated the use of DCM, EA, tetrahydrofuran (THF), chloroform, and acetone as the organic solvents in PLGA microparticle syntheses81. The highest E2 EE (97%) was achieved when using EA as the organic solvent, whereas the lowest E2 EE (52%) was seen when using acetone as the organic solvent81. E2 release was slowest with EA as the organic solvent, with 52% of E2 released in 120 hours, whereas 71%, 69%, 64%, and 72% E2 was released when DCM, THF, chloroform, and acetone were used as the organic solvents, respectively81. In summary, these studies point to EA as the organic solvent that results in highest E2 EE and slowest E2 release rate.

Size of PLGA particles

One study specifically investigated the release profile of E2 from 50:50 PLGA particles with a 100–4500 nm range in diameter size. The results from this study showed that the larger sized particles exhibit a decreased burst and slower initial release profile of E2 compared to the smaller sized particles25. Another study showed that both E2 PLA and E2 PLGA microparticles release E2 at a faster rate with smaller particle size80. Interestingly, it was observed in in vivo studies that smaller PLGA particles tended to exhibited a more sustained E2 release following oral administration compared to larger PLGA particles34,67. This may be in part explained by increased uptake of smaller PLGA MNCs by the intestinal epithelium19. Taken together, these studies indicate that particle size can play a role in the release profile of E2. Specifically, particles of smaller size released E2 at a faster rate but exhibited sustained E2 release following oral administration compared to larger particles, possibly due to differences in intestinal uptake of PLGA MNCs as a function of size.

Other modifications

PLGA has been blended with both natural and synthetic biomaterials to further alter E2 encapsulation and release. For instance, chitosan coating of E2 PLGA particles decreased the burst release as well as the initial release of E2 compared to gelatin coating25. Surface modifying PLGA microparticles with cationic polyamidoamine dendrimer resulted in an initial burst release of E2, followed by a slower E2 release whereby 98% of E2 was released within the first week35. Another common type of surface modification is the coating of PLGA particles with T-8040,55. This particular method has been shown to increase E2 concentration in the brain, plasma, kidneys, and heart at 24 hours and 48 hours following oral administration55. Taken together, these studies highlight how surface modification strategies of the PLGA MNCs can be utilized to obtain desired release profiles for E2 delivery.

Although we have focused primarily on MNC engineering with the intention that MNCs be administered as freely suspended agents, it is also possible to encapsulate MNCs within other biomaterial matrices to further alter release and distribution of E2. For example, E2 PLGA microparticles encapsulated in a silicone matrix decreased the initial burst in E2 release12. Interestingly, E2 was released at a faster rate from PLGA microparticles in the silicon matrix compared to free E2 in the silicone matrix, suggesting that the E2 release from PLGA microparticles within the silicone matrix was largely governed by diffusion of the hormone through pores formed as PLGA microparticles degraded12. Another example is loading E2 PLGA nanoparticles on chitosan-hydroxyapatite scaffolds to achieve a sustained E2 release profile. E2 PLGA nanoparticles were either embedded during or after scaffold fabrication, resulting in 55 day E2 release for E2 PLGA particles loaded after scaffold fabrication compared to the 135 day E2 release for E2 PLGA particles loaded during scaffold fabrication36. Also, encapsulation of E2 PLGA mixed with poly(ethylene glycol)-PLA copolymer in a gel plug delivery system resulted in 81.6 pg/ml (low dose) and 725.2 pg/ml (high dose) E2 plasma concentrations, compared to 15.9 pg/ml in the vehicle group, at 6 hours following local treatment using a spinal cord injury model17. Thus, the E2 EE and E2 release profile can be modified by not only altering synthesis parameters for PLGA MNCs, but also by the addition of other biomaterials to achieve desired results from an E2 treatment.

E2 delivery using PLGA MNCs

Delivery of E2 via PLGA MNCs produces distinct pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic profiles relative to free drug. E2 PLGA MNCs have been studied most commonly in the context of oral or transdermal administration. For instance, Dr. Kumar’s laboratory has analyzed the pharmacokinetics of E2 PLGA following oral administration as well as the effects of E2 PLGA oral treatment in a high-fat induced hyperlipidemic rat model and in an AD rat model55,56,57,58. Following 100 ug/kg E2 oral administration, they showed that E2 PLGA treatment resulted in a maximum E2 plasma level of 85 pg/ml at 24 hours, whereas E2 suspension resulted in a maximum E2 plasma level of 102 pg/ml at 4 hours57. When E2 plasma concentration is plotted across the collected time points, the area under the curve (AUC) in the plot represents the total circulating E2 over the measured period of time. Here, the AUC E2 levels following oral administration were 1290 pg h/ml and 6579 pg h/ml for E2 suspension and E2 PLGA, respectively57. Additionally, following oral administration, E2 PLGA formulations of varying molecular weight (14,500, 45,000 and 213,000 Da) and varying lactide to glycolide ratios (50:50, 65:35) each showed detectable levels of E2 5–11 days after administration, which was significantly longer compared to the dose matched free E2 oral delivery, with detectable levels seen for only 1 day after administration58. In a high-fat induced hyperlipidemic rat model, E2 PLGA treatment administered orally every 3 days for 2 weeks significantly reduced body weight compared to controls, whereas a daily oral administration of an E2 suspension did not have a significant effect on body weight56. On the other hand, the E2 PLGA treatment in an AD model was effective at preventing amyloid beta plaque formation, but no significant benefit was seen between orally administered E2 PLGA versus E2 suspension treatment55. Additional research has demonstrated that following oral administration, blood plasma AUC level for free E2 was 52 ng h/ml, but for E2 PLGA treatment blood plasma AUC levels were 1908 ng h/ml for formulations made using DMAB, and 2542 ng h/ml formulations made using PVA34 Interestingly, the blood plasma AUC level for intravenous administration of free E2 was 1344 ng h/ml34. Thus, orally administered E2 PLGA treatment achieved blood plasma AUC levels similar to those of intravenously administered free E2. In this same study, the time to reach maximum concentration for orally administered free E2 was 1.4 hours (Cmax 32 ng/ml), but 13 hours (Cmax 61 ng/ml) and 27 hours (Cmax 65 ng/ml) for E2 PLGA nanoparticles made with DMAB or with PVA, respectively34

In a study of transdermal administration, E2 PLGA applied to rat skin also had significantly higher levels of circulating E2 compared to that of free E2, suggesting enhanced permeability of E2 with the use of PLGA nanoparticles73. The addition of iontophoresis further enhanced the permeability of E2 PLGA following transdermal administration, resulting in greater E2 circulating levels and greater E2 levels in the muscle compared to free E2 and compared to E2 PLGA with no iontophoresis73. The enhanced permeability of E2 with PLGA MNCs, and with the addition of iontophoresis to PLGA MNCs, was tested for therapeutic efficacy in a rat model of osteoporosis. Results showed that a transdermal E2 PLGA treatment with iontophoresis increased bone mineral density, a marker of bone regeneration, for cortical but not cancellous bone compared to E2 PLGA treatment alone and compared to control71. The same laboratory was able to further enhance the therapeutic efficacy of transdermal E2 PLGA plus iontophoresis treatment on bone mineral density by forming PLGA MNCs with high surface charge density (82 times greater than that of regular E2 PLGA MNCs)72. Specifically, they showed that transdermal application of charged E2 PLGA MNCs with iontophoresis significantly increased E2 permeability relative to regular E2 PLGA MNCs with iontophoresis and relative to charged E2 PLGA MNCs without iontophoresis. The charged E2 PLGA MNCs with iontophoresis treatment was able to significantly increase cancellous bone mineral density compared to controls72. These findings are consistent with results from another laboratory, whereby, subcutaneous E2 PLGA microparticle treatment was shown to achieve sustained E2 circulating levels across 50 days and significantly increased bone mineral density in a rat model of osteoporosis, compared to vehicle control63. Taken together, studies show that encapsulation of E2 in PLGA nanoparticles results in increased circulating E2 concentration as well as increased circulation time of E2 following oral and transdermal administration compared to free E2. They also highlight that it is possible to alter specific parameters for PLGA synthesis to achieve different E2 pharmacokinetic profiles as well as therapeutic efficacy.

Due to sustained release of E2 from PLGA MNCs, the AUC circulating E2 levels following oral administration of E2 PLGA MNCs were comparable to that of an intravenous administration of free E2 suspension, and significantly greater than the AUC circulating E2 levels following orally administered free E2 suspension34,57,58. When tested in preclinical models of disease, E2 PLGA treatments were able to produce therapeutic effects that either enhanced or were at least equivalent to that of free E2 treatment55,56,63. Taken together, these preclinical studies provide initial therapeutic evidence for the use of E2 PLGA MNCs to treat different symptoms. Nevertheless, additional studies are still needed to optimize the therapeutic potential of E2 PLGA MNCs formulations for not only the symptoms associated with menopause, but also those associated with CNS diseases.

PLGA MNCs and other hormones

Although E2 is the most potent endogenous estrogen, there are several natural estrogens as well as synthetic estrogens that are also often used in hormone therapy. Some studies have examined these estrogens for EE and release profile analyses following encapsulation in PLGA MNCs. For example, a study examining synthesis parameters (i.e. percentage of PVA and ratio of DCM/ethanol/acetone) for encapsulation of estradiol valerate, a semisynthetic estrogen, in PLGA nanoparticles revealed that the addition of ethanol to the organic solvent mixture resulted in smaller sized particles26. Additionally, increasing the percentage of PVA decreased EE of estradiol valerate, with 55% EE of estradiol valerate achieved using 1% PVA and 9% EE of estradiol valerate achieved using 4% PVA, and increased the in vitro release of estradiol valerate from PLGA nanoparticles26. Another study encapsulated estradiol valerate into PLA microparticles and showed that a lower PLA polymer concentration resulted in a smaller particle size49. All formulations tested in this study exhibited a release profile of an initial burst release followed by slow sustained release49. A study examining 2 wt%, 5 wt%, and 10 wt% PLGA polymer concentration also noted that as polymer concentration was reduced, particle size and estradiol EE decreased (type of estradiol not specified)23. Additionally, slower estradiol release rate was seen from estradiol PLGA MNCs as polymer concentration was increased23. However, the addition of 30 seconds 22.5 kHz ultrasound enhanced estradiol release rate by 5.6%, 6.8%, and 7.8% for 2 wt%, 5 wt%, and 10 wt% estradiol PLGA MNCs, respectively23. The effect of PLGA polymer concentration on particle size and estradiol EE were replicated in a second study by the same laboratory24 Additionally, the authors examined how varying several parameters for ultrasound exposure impacted estradiol release rate, revealing that increasing output power, duty cycle, as well as exposure time increased estradiol release rate from PLGA MNCs24. Thus, multiple strategies for encapsulation in polymeric MNCs to achieve increased EE and sustained estrogen release can be effectively utilized for E2 as well as other types of estrogens.

Moreover, estrogen-based treatments must be opposed with a progestogen in the presence of a uterus due to the associated increase in the risk for developing endometrial hyperplasia with unopposed estrogen exposure59. Several studies have examined the release profiles of an estrogen plus progestogen encapsulated in PLGA MNCs combinations. One study assessed encapsulation of a synthetic estrogen, ethinyl estradiol, and a synthetic progestogen, levonorgestrel, in PLGA microparticles in order to achieve sustained release. Following intramuscular injection, these treatments showed an initial burst release of both ethinyl estradiol and levonorgestrel in rat blood serum that was followed by constant blood serum concentrations of 3 pg/ml ethinyl estradiol and 2 ng/ml levonorgestrel for ~13 weeks21. Another study assessed the release profile of ethinyl estradiol from PLGA microparticles and drospirenone, a type of synthetic progestogen, from PLGA microparticles in combination. Results showed sustained in vitro release profiles for each of the hormones for up to 300 hours60. A controlled release study was also done for ethinyl estradiol and gestodene, another type of synthetic progestogen, from PLGA microparticles. In this study, the in vitro release profile for both hormones was similar, with fast release within the first 5 days, followed by slow release that lasted up to 35 days70. Following subcutaneous injection, the concentration of ethinyl estradiol and gestodene suspensions peaked within the first 30 minutes and then rapidly decreased, whereas the concentration of each hormone delivered together within PLGA microparticles reached peak concentrations on day 3 for ethinyl estradiol and on day 1 for gestodene, and exhibited a sustained release profile for both hormones70. Taken together, these studies suggest that polymeric MNCs are a useful resource that can be employed to achieve desired release profiles of clinically-relevant combination hormone therapy treatments.

Conclusion

E2-based hormone therapy is clinically approved for treatment of symptoms associated with menopause. However, in women with a uterus, all E2-based hormone treatments must be accompanied by an opposing progestogen to offset undesired E2 exposure in the uterine tissue. The addition of a progestogen can also offset beneficial effects of E2 as seen with its neuroprotective and cognitive effects, limiting the therapeutic potential of E2 in CNS related functions and diseases (i.e. AD). Drug carriers such as PLGA MNCs could be used to enhance the therapeutic potential of E2 in the CNS. Here, we discussed how systematically varying the parameters and route of administration of E2 PLGA MNCs influences the release and EE of E2, resulting in distinct pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic profiles. Additionally, we discuss preliminary evidence that suggests encapsulation of E2 in PLGA MNCs can enhance the therapeutic efficacy of E2-based treatments.

There are multiple strategies in the field of drug delivery that have yet to be explored to achieve enhanced delivery of E2 PLGA MNCs to the CNS. PLGA MNCs can be surface modified with compounds that may increase brain uptake of the particles, such as by taking advantage of specific transport mechanisms across the blood brain barrier14,42,51,55 For example, Mittal et al., (2011) showed increased E2 delivery to the brain following oral administration of T-80 surface coated E2 PLGA MNCs compared to non-coated E2 PLGA MNCs42. Route of administration is another tool that can potentially enhance E2 PLGA MNCs delivery to the CNS. Several studies suggest that intranasal administration of agents results in increased delivery to the brain versus peripheral tissues compared to alternate administration routes47,61. Moreover, the intranasal route has already been previously used clinically as a nasal E2 spray aimed at treating symptoms associated with menopause. We propose that further work examining various surface modification and route of administration strategies of E2 PLGA MNCs is necessary to build on the growing body of literature and to attain an enhanced therapeutic effect of E2 in the CNS using PLGA MNCs. These two strategies have already been combined to achieve enhanced agent uptake in the CNS using PLGA MNCs, such as with rotigotine (treatment for Parkinson’s disease) where enhanced CNS uptake was achieved via intranasal administration of lactoferrin surface-modified poly(ethylene glycol)-PLGA MNCs6. In a similar manner, E2 delivery to the CNS can be potentially enhanced with surface modified PLGA MNC for CNS-targeted delivery via the intranasal route of administration. The effective development of novel E2 treatment formulations, using PLGA MNCs, will provide novel avenues for treatment of symptoms associated with reproductive senescence as well as those associated with CNS diseases.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the Barrow Neurological Institute and the ASU-BNI Interdepartmental Neuroscience Program. Alesia Prakapenka is funded by the NSF Graduate Research Fellowship. Dr. Heather Bimonte-Nelson is funded by NIA (AG028084), state of Arizona, and Arizona Department of Health Services (ADHS 14-052688).

Abbreviations, symbols, and terminology

- AD

Alzheimer’s disease

- CNS

central nervous system

- DCM

dichloromethane

- DMAB

didodecyldimethyl ammonium bromide

- E1

estrone

- E2

17β-estradiol

- EA

ethyl acetate

- EE

encapsulation efficiency

- Erk2

extracellular signal-regulated kinase 2

- MNC

micro- and nano- carriers

- PLA

polylactic acid

- PLGA

poly (lactic co-glycolic) acid

- PVA

polyvinyl alcohol

- SLS

sodium lauryl sulfate

- T-80

Tween-80

- THF

tetrahydrofuran

References

- 1.Anderson DC. Sex-hormone-binding globulin. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 1974;3:69–96. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.1974.tb03298.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anderson JM, Shive MS. Biodegradation and biocompatibility of PLA and PLGA microspheres. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 1997;28:5–24. doi: 10.1016/s0169-409x(97)00048-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Asthana S, Baker LD, Craft S, Stanczyk FZ, Veith RC, Raskind MA, Plymate SR. High-dose estradiol improves cognition for women with AD: results of a randomized study. Neurology. 2001;57:605–612. doi: 10.1212/wnl.57.4.605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baker LD, Sambamurti K, Craft S, Cherrier M, Raskind MA, Stanczyk FZ, Plymate SR, Asthana S. 17β-estradiol reduces plasma Aβ 40 for HRT-naive postmenopausal women with Alzheimer disease - A preliminary study. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2003;11:239–244. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barichello JM, Morishita M, Takayama K, Nagai T. Encapsulation of hydrophilic and lipophilic drugs in PLGA nanoparticles by the nanoprecipitation method. Drug Dev Ind Pharm. 1999;25:471–476. doi: 10.1081/ddc-100102197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bi C, Wang A, Chu Y, Liu S, Mu H, Liu W, Wu Z, Sun K, Li Y. Intranasal delivery of rotigotine to the brain with lactoferrin-modified PEG-PLGA nanoparticles for Parkinson’s disease treatment. Int J Nanomedicine. 2016;11:6547–6559. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S120939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bimonte-Nelson HA, Francis KR, Umphlet CD, Granholm AC. Progesterone reverses the spatial memory enhancements initiated by tonic and cyclic oestrogen therapy in middle-aged ovariectomized female rats. Eur J Neurosci. 2006;24:229–242. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2006.04867.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bimonte-Nelson HA, Nelson ME, Granholm AE. Progesterone counteracts estrogen-induced increases in neurotrophins in the aged female rat brain. Neuroreport. 2004;15:2659–63. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200412030-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Birnbaum DT, Kosmala JD, Henthorn DB, Brannon-Peppas L. Controlled release of β-estradiol from PLAGA microparticles: The effect of organic phase solvent on encapsulation and release. J Control Release. 2000;65:375–387. doi: 10.1016/s0168-3659(99)00219-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Blum S, Moore AN, Adams F, Dash PK. A mitogen-activated protein kinase cascade in the CA1/CA2 subfield of the dorsal hippocampus is essential for long-term spatial memory. J Neurosci. 1999;19:3535–44. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-09-03535.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bodor N, Buchwald P. Barriers to remember: Brain-targeting chemical delivery systems and Alzheimer’s disease. Drug Discov Today. 2002;7:766–774. doi: 10.1016/s1359-6446(02)02332-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brannon-Peppas L. Controlled release of β-estradiol from biodegradable microparticles within a silicone matrix. J Biomater Sci Polym ed. 1994;5:339–351. doi: 10.1163/156856294x00068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Buch A, Shen L, Kelly S, Sahota R, Brezovic C, Bixler C, Powell J. Steady-state bioavailability of estradiol from two matrix transdermal delivery systems, Alora and Climara. Menopause J North Am Menopause Soc. 1998;5:107–112. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cai Q, Wang L, Deng G, Liu J, Chen Q, Chen Z. Systemic delivery to central nervous system by engineered PLGA nanoparticles. Am J Transl Res. 2016;8:749–764. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chasin M, Langer R. Biodegradable Polymers as Drug Delivery Systems. Marcel Dekker, Inc; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cholerton B, Gleason CE, Baker LD, Asthana S. Estrogen and Alzheimer’s disease: the story so far. Drugs Aging. 2002;19:405–427. doi: 10.2165/00002512-200219060-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cox A, Varma A, Barry J, Vertegel A, Banik N. Nanoparticle estrogen in rat spinal cord injury elicits rapid anti-Inflammatory effects in plasma, cerebrospinal fluid, and tissue. J Neurotrauma. 2015;32:1413–1421. doi: 10.1089/neu.2014.3730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Danhier F, Ansorena E, Silva JM, Coco R, Breton A Le, Préat V. PLGA-based nanoparticles: An overview of biomedical applications. J Control Release. 2012;161:505–522. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2012.01.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Desai MP, Labhasetwar V, Walter E, Levy RJ, Amidon GL. The mechanism of uptake of biodegradable microparticles in Caco-2 cells is size dependent. Pharm Res. 1997;14:1568–1573. doi: 10.1023/a:1012126301290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Devissaguet JP, Brion N, Lhote O, Deloffre P. Pulsed estrogen therapy: pharmacokinetics of intranasal 17-beta-estradiol (S21400) in postmenopausal women and comparison with oral and transdermal formulations. Eur J Drug Metab Pharmacokinet. 1999;24:265–71. doi: 10.1007/BF03190030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dhanaraju MD, RajKannan R, Selvaraj D, Jayakumar R, Vamsadhara C. Biodegradation and biocompatibility of contraceptive-steroid-loaded poly (DL-lactide-co-glycolide) injectable microspheres: in vitro and in vivo study. Contraception. 2006;74:148–156. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2006.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dinarvand R, Sepehri N, Manoochehri S, Rouhani H, Atyabi F. Polylactide-co-glycolide nanoparticles for controlled delivery of anticancer agents. Int J Nanomedicine. 2011;6:877–895. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S18905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Enayati M, Ahmad Z, Stride E, Edirisinghe M. One-step electrohydrodynamic production of drug-loaded micro- and nanoparticles. J R Soc Interface. 2010;7:667–75. doi: 10.1098/rsif.2009.0348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Enayati M, Edirisinghe M, Stride E. Ultrasound-stimulated drug release from polymer micro and nanoparticles. Bioinspired, Biomim Nanobiomaterials. 2012;2:3–10. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Enayati M, Stride E, Edirisinghe M, Bonfield W. Modification of the release characteristics of estradiol encapsulated in PLGA particles via surface coating. Ther Deliv. 2012;3:209–226. doi: 10.4155/tde.11.154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Esmaeili F, Atyabi F, Dinarv R. Preparation and characterization of estradiol-loaded PLGA nanoparticles using homogenization-solvent diffusion method. DARU. 2008;16:196–202. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fernandez SM, Lewis MC, Pechenino AS, Lauren L, Orr PT, Gresack JE, Schafe GE, Frick KM. Estradiol-induced enhancement of object memory consolidation involves hippocampal Erk activation and membrane-bound estrogen receptors. J Neurosci. 2008;28:8660–8667. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1968-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fredenberg S, Wahlgren M, Reslow M, Axelsson A. The mechanisms of drug release in poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid)-based drug delivery systems–a review. Int J Pharm. 2011;415:34–52. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2011.05.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ginsburg ES, Gao X, Shea BF, Barbieri RI. Half-life of estradiol in postmenopausal women. Gynecol Obstet Invest. 1998;45:45–48. doi: 10.1159/000009923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Grabnar PA, Kristl J. The manufacturing techniques of drug-loaded polymeric nanoparticles from preformed polymers. J Microencapsul. 2011;28:323–35. doi: 10.3109/02652048.2011.569763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hadavi D, Poot AA. Biomaterials for the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease. Front Bioeng Biotechnol. 2016;4:1–10. doi: 10.3389/fbioe.2016.00049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Harburger LL, Bennett JC, Frick KM. Effects of estrogen and progesterone on spatial memory consolidation in aged females. Neurobiol Aging. 2007;28:602–610. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2006.02.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Harburger LL, Saadi A, Frick KM. Dose-dependent effects of post-training estradiol plus progesterone treatment on object memory consolidation and hippocampal extracellular signal-regulated kinase activation in young ovariectomized mice. Neuroscience. 2009;160:6–12. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2009.02.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hariharan S, Bhardwaj V, Bala I, Sitterberg J, Bakowsky U, Kumar MNV Ravi. Design of estradiol loaded PLGA nanoparticulate formulations: A potential oral delivery system for hormone therapy. Pharm Res. 2006;23:184–195. doi: 10.1007/s11095-005-8418-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hong L, Krishnamachari Y, Seabold D, Joshi V, Schneider G, Salem AK. Intracellular release of 17-β estradiol from cationic polyamidoamine dendrimer surface-modified poly (lactic-co-glycolic acid) microparticles improves osteogenic differentiation of human mesenchymal stromal cells. Tissue Eng. 2011;17:319–325. doi: 10.1089/ten.tec.2010.0388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Irmak G, Demirtaş TT, Altindal DÇ, Çaliş M, Gumusderelioglu M. Sustained release of 17β-estradiol stimulates osteogenic differentiation of adipose tissue-derived mesenchymal stem cells on chitosan-hydroxyapatite scaffolds. Cells Tissues Organs. 2014;199:37–50. doi: 10.1159/000362362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jain RA. The manufacturing techniques of various drug loaded biodegradable poly(lactide-co-glycolide) (PLGA) devices. Biomaterials. 2000;21:2475–2490. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(00)00115-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jayaraman A, Carroll JC, Morgan TE, Lin S, Zhao L, Arimoto JM, Murphy MP, Beckett TL, Finch CE, Brinton RD, Pike CJ. 17β-Estradiol and progesterone regulate expression of β-amyloid clearance factors in primary neuron cultures and female rat brain. Endocrinology. 2012;153:5467–5479. doi: 10.1210/en.2012-1464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kamaly N, Xiao Z, Valencia PM, Radovic-Moreno AF, Farokhzad OC. Targeted polymeric therapeutic nanoparticles: design, development and clinical translation. Chem Soc Rev. 2012;41:2971–3010. doi: 10.1039/c2cs15344k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kim JH, Kim GH, Jeong JH, Lee IH, Lee YJ, Lee NS, Jeong YG, Lee JH, Yu KS, Lee SH, Hong SK, Kang SH, Kang BS, Kim DK, Han SY. Neuroprotective effect of estradiol-loaded poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) nanoparticles on glutamate-induced excitotoxic neuronal death. J Nanosci Nanotechnol. 2014;14:8390–8397. doi: 10.1166/jnn.2014.9926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Koebele SV, Bimonte-Nelson HA. Trajectories and phenotypes with estrogen exposures across the lifespan: What does Goldilocks have to do with it? Horm Behav. 2015;74:86–104. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2015.06.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kreuter J. Drug delivery to the central nervous system by polymeric nanoparticles: What do we know? Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2014;71:2–14. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2013.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kuhl H. Pharmacology of estrogens and progestogens: influence of different routes of administration. Climacteric. 2005;8:3–63. doi: 10.1080/13697130500148875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kuhnz W, Gansau C, Mahler M. Pharmacokinetics of estradiol, free and total estrone, in young women following single intravenous and oral administration of 17 beta-estradiol. Arzneimittelforschung. 1993;43:966–973. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kumari A, Yadav SK, Yadav SC. Biodegradable polymeric nanoparticles based drug delivery systems. Colloids Surfaces B Biointerfaces. 2010;75:1–18. doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2009.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lobo RA. Treatment of the Postmenopausal Woman: Basic and Clinical Aspects. Academic Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lochhead JJ, Thorne RG. Intranasal delivery of biologics to the central nervous system. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2012;64:614–628. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2011.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lowry NC, Pardon LP, Yates MA, Juraska JM. Effects of long-term treatment with 17 β-estradiol and medroxyprogesterone acetate on water maze performance in middle aged female rats. Horm Behav. 2010;58:200–207. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2010.03.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Machado SRP, Lunardi LO, Tristão AP, Marchetti JM. Preparation and characterization of D, L-PLA loaded 17-β-Estradiol valerate by emulsion/evaporation methods. J Microencapsul. 2009;26:202–213. doi: 10.1080/02652040802233786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Maki PM. Minireview: Effects of different HT formulations on cognition. Endocrinology. 2012;153:3564–3570. doi: 10.1210/en.2012-1175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.McCall RL, Cacaccio J, Wrabel E, Schwartz ME, Coleman TP, Sirianni RW. Pathogen-inspired drug delivery to the central nervous system. Tissue Barriers. 2014;2:e944449. doi: 10.4161/21688362.2014.944449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.McCall RL, Sirianni RW. PLGA nanoparticles formed by single- or double-emulsion with vitamin E-TPGS. J Vis Exp. 2013;82:51015. doi: 10.3791/51015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mennenga SE, Bimonte-Nelson HA. Translational cognitive endocrinology: Designing rodent experiments with the goal to ultimately enhance cognitive health in women. Brain Res. 2013;1514:50–62. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2013.01.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Mennenga SE, Bimonte-Nelson HA. The importance of incorporating both sexes and embracing hormonal diversity when conducting rodent behavioral assays. In: Bimonte-Nelson HA, editor. The Maze Book: Theories, Practice, and Protocols for Testing Rodent Cognition. Humana Press; 2015. pp. 299–321. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Mittal G, Carswell H, Brett R, Currie S, Kumar MNVR. Development and evaluation of polymer nanoparticles for oral delivery of estradiol to rat brain in a model of Alzheimer’s pathology. J Control Release. 2011;150:220–228. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2010.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Mittal G, Chandraiah G, Ramarao P, Kumar MNV Ravi. Pharmacodynamic evaluation of oral estradiol nanoparticles in estrogen deficient (ovariectomized) high-fat diet induced hyperlipidemic rat model. Pharm Res. 2009;26:218–223. doi: 10.1007/s11095-008-9725-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Mittal G, Kumar MNVR. Impact of polymeric nanoparticles on oral pharmacokinetics: A dose-dependent case study with estradiol. J Pharm Sci. 2009;98:3730–3734. doi: 10.1002/jps.21695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Mittal G, Sahana DK, Bhardwaj V, Kumar MNV Ravi. Estradiol loaded PLGA nanoparticles for oral administration: Effect of polymer molecular weight and copolymer composition on release behavior in vitro and in vivo. J Control Release. 2007;119:77–85. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2007.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.NAMS. The 2012 hormone therapy position statement of The North American Menopause Society (NAMS) Menopause J North Am Menopause Soc. 2012;19:257–271. doi: 10.1097/gme.0b013e31824b970a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Nippe S, General S. Combination of injectable ethinyl estradiol and drospirenone drug-delivery systems and characterization of their in vitro release. Eur J Pharm Sci. 2012;47:790–800. doi: 10.1016/j.ejps.2012.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Nonaka N, Farr SA, Kageyama H, Shioda S, Banks WA. Delivery of galanin-like peptide to the brain: targeting with intranasal delivery and cyclodextrins. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2008;325:513–519. doi: 10.1124/jpet.107.132381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.O’Donnell PB, McGinity JW. Preparation of microspheres by the solvent evaporation technique. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 1997;28:25–42. doi: 10.1016/s0169-409x(97)00049-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Otsuka M, Uenodan H, Matsuda Y, Mogi T, Ohshima H, Makino K. Therapeutic effect of in vivo sustained estradiol release from poly (lactide-co-glycolide) microspheres on bone mineral density of osteoporosis rats. Biomed Mater Eng. 2002;12:157–167. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Pelissier C, Kervasdoue A De, Chuong VT, Maugis EL, Mouillac F De, Breil MH, Moniot G, Zeitoun-Lepvrier G, Robin M, Rime B. Clinical evaluation, dose-finding and acceptability of AERODIOL, the pulsed estrogen therapy for treatment of climacteric symptoms. Maturitas. 2001;37:181–189. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5122(00)00175-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Reginster JY, Albert A, Deroisy R, Colette J, Vrijens B, Blacker C, Brion N, Caulin F, Mayolle C, Regnard A, Scholler R, Franchimont P. Plasma estradiol concentrations and pharmacokinetics following transdermal application of Menorest® 50 or Systen® (Evorel®) 50. Maturitas. 1997;27:179–186. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5122(97)00027-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ruoff WL, Dziuk PJ. Absorption and metabolism of estrogens from the stomach and duodenum of pigs. Domest Anim Endocrinol. 1994;11:197–208. doi: 10.1016/0739-7240(94)90027-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Sahana DK, Mittal G, Bhardwaj V, Kumar MN. PLGA nanoparticles for oral delivery of hydrophobic drugs: Influence of organic solvent on nanoparticle formation and release behavior in vitro and in vivo using estradiol as a model drug. J Pharm Sci. 2007;97:1530–1542. doi: 10.1002/jps.21158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Satishkumar R, Vertegel AA. Antibody-directed targeting of lysostaphin adsorbed onto polylactide nanoparticles increases its antimicrobial activity against S. aureus in vitro. Nanotechnology. 2011;22:505103. doi: 10.1088/0957-4484/22/50/505103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Studd J, Pornel B, Marton I, Bringer J, Varin C, Tsouderos Y, Christiansen C. Efficacy and acceptability of intranasal 17 β-oestradiol for menopausal symptoms: Randomised dose-response study. Lancet. 1999;353:1574–1578. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(98)06196-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Sun Y, Wang J, Zhang X, Zhang Z, Zheng Y, Chen D, Zhang Q. Synchronic release of two hormonal contraceptives for about one month from the PLGA microspheres: In vitro and in vivo studies. J Control Release. 2008;129:192–199. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2008.04.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Takeuchi I, Fukuda K, Kobayashi S, Makino K. Transdermal delivery of estradiol-loaded PLGA nanoparticles using iontophoresis for treatment of osteoporosis. Biomed Mater Eng. 2016;27:475–483. doi: 10.3233/BME-161601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Takeuchi I, Kobayashi S, Hida Y, Makino K. Estradiol-loaded PLGA nanoparticles for improving low bone mineral density of cancellous bone caused by osteoporosis: Application of enhanced charged nanoparticles with iontophoresis. Colloids Surfaces B Biointerfaces. 2017;155:35–40. doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2017.03.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Tomoda K, Watanabe A, Suzuki K, Inagi T, Terada H, Makino K. Enhanced transdermal permeability of estradiol using combination of PLGA nanoparticles system and iontophoresis. Colloids Surfaces B Biointerfaces. 2012;97:84–89. doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2012.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.US FDA’s Office of Women’s Health. Menopause: medicines to help you. 2015 at< http://www.fda.gov/ForConsumers/ByAudience/ForWomen/ucm118627.htm>.

- 75.Valenzuela P, Simon JA. Nanoparticle delivery for transdermal HRT. Nanomedicine Nanotechnology, Biol Med. 2012;8:S83–S89. doi: 10.1016/j.nano.2012.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Wharton W, Baker LD, Gleason CE, Dowling M, Barnet JH, Johnson S, Carlsson C, Craft S, Asthana S. Short-term hormone therapy with transdermal estradiol improves cognition for postmenopausal women with Alzheimer’s disease: results of a randomized controlled trial. J Alzheimer’s Dis. 2011;26:495–505. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2011-110341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.White CM, Ferraro-Borgida MJ, Fossati AT, McGill CC, Ahlberg AW, Feng YJ, Heller GV, Chow MSS. The pharmacokinetics of intravenous estradiol — a preliminary study. Pharmacotherapy. 1998;18:1343–1346. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Witschi C, Doelker E. Influence of the microencapsulation method and peptide loading on poly(lactic acid) and poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) degradation during in vitro testing. J Control Release. 1998;51:327–341. doi: 10.1016/s0168-3659(97)00188-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Xie J, Lim LK, Phua Y, Hua J, Wang C. Electrohydrodynamic atomization for biodegradable polymeric particle production. J Colloid Interface Sci. 2006;301:103–112. doi: 10.1016/j.jcis.2006.06.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Xinteng Z, Weisan P, Ruhua Z, Feng Z. Preparation and evaluation of poly (D, L — lactic acid) (PLA) or D, L-lactide/glycolide copolymer (PLGA) microspheres with estradiol. Pharmazie. 2002;57:695–697. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Zaghloul AA. β-estradiol biodegradable microspheres: Effect of formulation parameters on encapsulation efficiency and in vitro release. Pharmazie. 2006;61:775–779. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Zaghloul AA, Mustafa F, Siddiqu A, Khan M. Biodegradable microparticulates of beta-estradiol: preparation and in vitro characterization. Drug Dev Ind Pharm. 2005;31:803–811. doi: 10.1080/03639040500217624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Zhao L, Brinton RD. Estrogen receptor α and β differentially regulate intracellular Ca2+ dynamics leading to ERK phosphorylation and estrogen neuroprotection in hippocampal neurons. Brain Res. 2007;1172:48–59. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2007.06.092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Zhao L, Yao J, Mao Z, Chen S, Wang Y, Brinton RD. 17β-Estradiol regulates insulin-degrading enzyme expression via an ERβ/PI3-K pathway in hippocampus: relevance to Alzheimer’s prevention. Neurobiol Aging. 2011;32:1949–1963. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2009.12.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]